Abstract

Female genital tuberculosis (FGTB) is an important cause of significant morbidity, short- and long-term sequelae especially infertility whose incidence varies from 3 to 16 % cases in India. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the etiological agent for tuberculosis. The fallopian tubes are involved in 90–100 % cases, endometrium is involved in 50–80 % cases, ovaries are involved in 20–30 % cases, and cervix is involved in 5–15 % cases of genital TB. Tuberculosis of vagina and vulva is rare (1–2 %). The diagnosis is made by detection of acid-fast bacilli on microscopy or culture on endometrial biopsy or on histopathological detection of epithelioid granuloma on biopsy. Polymerase chain reaction may be false positive and alone is not sufficient to make the diagnosis. Laparoscopy and hysteroscopy can diagnose genital tuberculosis by various findings. Treatment is by giving daily therapy of rifampicin (R), isoniazid (H), pyrazinamide (Z) and ethambutol (E) for 2 months followed by daily 4 month therapy of rifampicin (R) and isoniazid (H). Alternatively 2 months intensive phase of RHZE can be daily followed by alternate day combination phase (RH) of 4 months. Three weekly dosing throughout therapy (RHZE thrice weekly for 2 months followed by RH thrice weekly for 4 months) can be given as directly observed treatment short-course. Surgery is rarely required only as drainage of abscesses. There is a role of in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer in women whose fallopian tubes are damaged but endometrium is healthy. Surrogacy or adoption is needed for women whose endometrium is also damaged.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tuberculosis continues to be a major health problem throughout the world affecting about 9.4 million people annually with about two million deaths [1, 2]. Over 95 % of new TB cases and deaths occur in developing countries with India and China together accounting for 40 % of the world’s TB burden. Co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), more liberal immigration from high risk to low risk areas due to globalization has been responsible for increased incidence all over the world. Multidrug resistant (MDR) and extreme-drug resistant TB (XDR), usually caused by poor case management, are a cause of serious concern [1, 2].

World Health Organization (WHO) in a drastic step declared TB a global emergency in 1993 and promoted a new effective TB control called Directly Observed Treatment Short-course (DOTS) strategy with 70 % case detection rate and 85 % successfully treatment rates [3]. The Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) of India incorporating DOTS strategy has achieved 100 % geographical coverage with 71 % case detection rate and 87 % treatment success rate with a sevenfold decrease in death rate (from 29 to 4 %) in the year of 2010 [4].

Apart from commonest and the most infectious pulmonary TB, extra pulmonary TB (EPTB) is being increasingly encountered throughout the world [5]. Female genital TB (FGTB) is an important cause of significant morbidity, short- and long-term sequelae especially infertility [5–8]. Timely diagnosis and prompt appropriate treatment may prevent infertility and other sequelae of the disease.

Epidemiology

The incidence of FGTB varies in different countries from 1 % in infertility clinics of USA, 6.15–21.1 % in South Africa and 1–19 % in various parts of India [7, 9–13]. In infertility patients, incidence of FGTB varies from 3 to 16 % in India with higher incidence being from apex institutes like All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, where prevalence of FGTB in women of infertility was 26 % and incidence of infertility in FGTB to be 42.5 %, which may be due to referral of difficult and intractable cases to this apex hospital from all over India, especially from states like Bihar where prevalence of TB is very high [8, 13]. Similarly incidence of FGTB is also very high in women seeking assisted reproduction being 24.5 % overall but as high as 48.5 % with tubal factor infertility [14]. The FGTB is present in younger age (20–40 years) as compared to premenopausal age in developed countries [6, 8–15]. It may be due to younger age at marriage and child bearing in developing countries as compared to western world [8]. There has been fivefold increase in overall incidence of TB in countries with high prevalence of HIV due to impaired immunity in them [16].

Etiopathogenesis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the etiological agent for tuberculosis. Predisposing factors for TB include factors reducing personal immunity like poverty, overcrowding with improper ventilation, inadequate access to health care, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, smoking, alcohol and drug abuse, end stage renal disease cancer treatment hemodialysis patients and patient with HIV infection [1–3, 5–8, 16]. Genital TB generally occurs secondary to pulmonary (commonest) or extra pulmonary TB like gastro-intestinal tract, kidneys, skeletal system, meninges and miliary TB [5–8] through hematogenous and lymphatic route. However, primary genital TB can rarely occur in women whose male partners have active genitourinary TB (e.g., tuberculosis epididymitis) by transmission through infected semen [5, 8]. The site of involvement in primary genital TB can be cervix, vagina or vulva [5, 8]. Direct contiguous spread from nearby abdominal organs like intestines or abdominal lymph nodes can also cause genital TB. The fallopian tubes are involved in 90–100 % cases with congestion, military tubercles, hydrosalpinx, pyosalpinx and tubo-ovarian masses [5, 8]. Endometrium is involved in 50–80 % cases with caseation and ulceration causing intrauterine adhesions (Asherman’s syndrome) [17]. Ovaries are involved in 20–30 % cases with tubo-ovarian masses [5, 8]. Cervical TB may be seen in 5–15 % cases of genital TB and may masquerade cervical cancer necessitating biopsy for confirmation of diagnosis with granulomatous lesion [18]. Tuberculosis of vagina and vulva is rare (1–2 %) with a hypertrophic lesion or a nonhealing ulcer mimicking malignancy needing biopsy and histopathological examination to confirm the diagnosis. Rarely TB of the vagina can cause involvement of Bartholin’s glands, vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistula formation [19]. Peritoneal TB can be a disseminated form of TB with tubercles all over the peritoneum, intestines and omentum and may cause ascites and abdominal mass. It may masquerade as ovarian cancer as even CA 125 levels are raised in peritoneal TB with CT scan and MRI also giving similar picture and diagnosis may be made only on laparotomy done for suspected ovarian cancer [20, 21]. Ascitic fluid tapping for bio-chemical analysis (elevated adenosine deaminase level in ascitic fluid in peritoneal TB) is useful in diagnosis [22]. Laparoscopic biopsy with frozen section evaluation has also been suggested to avoid laparotomy in such cases [21, 22]. Positron emission tomography with 18 F-fluorodeoxy glucose (FDG-PET) has been successfully used for the preoperative diagnosis of peritoneal tuberculosis and tuberculous tubo-ovarian masses [23, 24]. Varying grades of pelvic and abdominal adhesions including perihepatic adhesions (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome) are common in genital and peritoneal tuberculosis [25, 26]. Rarely genital TB may be associated with other gynecological pathologies like ovarian cancer, genital prolapse and fibroid uterus [5–8].

Clinical Features

The clinical presentation of genital TB depends upon the site of involvement of genital organs and is shown in Table 1 [5, 8, 11, 27]. Up to 11 % of women with genital TB may be asymptomatic [8, 13]. The age of presentation in 80 % of women is 20–40 years age group especially in developing countries. Infertility is the commonest presentation of genital TB due to the involvement of fallopian tubes (blocked and damaged tubes), endometrium (non-reception and damaged endometrium with Asherman’s syndrome) and ovarian damage with poor ovarian reserve and volume [6–8, 17, 28].

The various signs of FGTB depend on the site of involvement of genital organs and are shown in Table 1 [5, 6, 8, 18–21, 28].

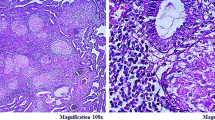

Diagnosis

Being a paucibacillary disease, demonstration of mycobacterium tuberculosis is not possible in all the cases. A high index of suspicion is required. The diagnostic dilemma arises due to varied clinical presentation, diverse results on imaging and endoscopy and availability of battery of bacteriological, serological and histopathological tests which are often required to get a collective evidence of the diagnosis of genital TB [8, 11]. The diagnostic approach used is family history of TB or history of antituberculous therapy (ATT) in a close family member or a past history of TB or ATT in the patient may show recrudescence of TB in the genital region. History of HIV positivity is also important. Detailed general physical examination for any lymphadenopathy and any evidence of TB at any other site in body (bones, joints, skin, etc.), chest examination (PTB), abdominal examination (abdominal TB), examination of external genitalia (vulvar or vaginal TB), speculum examination (cervical TB), bimanual examination (endometrial or fallopian tube TB) help in the diagnosis of genital TB [5, 6, 8, 18].

All tests are not required for every single case of genital TB. The tests will depend upon the site of TB and its clinical presentation. The various tests are shown in Table 3 [29–33].

Role of Endoscopy in FGTB

Hysteroscopy

Endoscopic visualization of the uterine cavity in genital TB may show a normal cavity (if no endometrial TB or early stage TB) with bilateral open ostia. More often, however, the endometrium is pale looking, and the cavity is partially or completely obliterated by adhesions of varying grade (grade 1 to grade 4) often involving ostia as observed by us (Fig. 2) [34]. There may be a small shrunken cavity. In our study on hysteroscopy in genital TB, we observed increased difficulty to distend the cavity and to do the procedure and increased chances of complications like excessive bleeding, perforation and flare-up of genital TB [35]. Hence, hysteroscopy in a patient with genital TB should be done by an experienced person preferably under laparoscopic guidance to avoid false passage formation and injury to the pelvic organs.

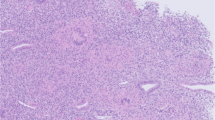

Laparoscopy (Figs. 3, 4)

A laparoscopy and dye hydrotubation (lap and dye test) is the most reliable tool to diagnose genital TB, especially for tubal, ovarian and peritoneal disease [8, 36]. The test can be combined with hysteroscopy for more information as follows [8, 34, 36].

-

1.

In subacute stage, there may be congestion, edema and adhesions in pelvic organs with multiple fluid-filled pockets. There are miliary tubercles, white yellow and opaque plaques over the fallopian tubes and uterus.

-

2.

In chronic stage, there may be following abnormalities.

-

a.

Yellow small nodules on tubes (nodular salpingitis).

-

b.

Short and swollen tubes with agglutinated fimbriae (patchy salpingitis.

-

c.

Unilateral or bilateral hydrosalpinx with retort-shaped tubes due to agglutination of fimbriae.

-

d.

Pyosalpinx or caseosalpinx: The tube usually bilateral is distended with caseous material with ovoid white yellow distension of ampulla with poor vascularization.

-

e.

Caseous nodules may be seen (Fig. 4).

-

a.

Adhesions

Various types of adhesions may be present in genital TB covering genital organs with or without omentum and intestines. There is very high prevalence (48 %) of perihepatic adhesions on laparoscopy in FGTB cases (Fig. 3) [25, 26]. In a laparoscopic study on 85 women with FGTB, we observed tubercles on peritoneum (15.9 % cases), tubo-ovarian masses (26 %), caseous nodules (7.2 %), encysted ascites (8.7 %), various grades of pelvic adhesions (65.8 %), hydrosalpinx (21.7 %), pyosalpinx (2.9 %), beaded tubes (10 %), tobacco pouch appearance (2.9 %) and inability to see tubes due to adhesions (14.2 %) [36]. We also observed increased complications on laparoscopy for FGTB as compared to laparoscopy performed for non-tuberculous patients (31 vs 4 %) like inability to see pelvis (10.3 vs 1.3 %), excessive bleeding (2.3 vs 0 %), peritonitis (8 vs 1.8 %) [37]. The adhesions are typically vascular, and adhesiolysis can increase the risk of bleeding and flare-up of the disease [8, 36, 37].

Combination of Tests (Algorithm)

The final diagnosis is made from good history taking, careful systemic and gynecological examination and judicious use of diagnostic modalities like endometrial biopsy in conjunction with imaging methods and endoscopic visualization especially with laparoscopy. Some authors have developed an algorithm for accurate diagnosis of FGTB by combining history taking, examination and investigations [11, 38].

Treatment

Medical Treatment

Multiple drug therapy in adequate doses and for sufficient duration is the main stay in the treatment of TB including FGTB. In olden days before rifampicin, the antituberculous therapy (ATT) was given for 18–24 months with significant side effects and poor compliance. Short-course chemotherapy for 6–9 months has been found to be effective for medical treatment of FGTB [39]. In a study funded by Central TB Division, Ministry of Health, Govt. of India, we observed 6-month intermittent DOTS therapy to be equally effective to 9-month therapy.

DOTS (Directly Observed Treatment Short-Course) Strategy Treatment

American Thoracic Society [40] and British Thoracic Society and NICE (National Institute of Clinical Excellence) Guidelines (2006) [41] recommend that first choice of treatment should be the ‘standard recommended regimen’ using a daily dosing schedule using combination tablets and does not consider DOTS necessary in management of most cases of TB in developed countries who can adhere to treatment. DOTS is favored by WHO to prevent MDR and for better results. WHO in its recent guidelines has removed category 3 and recommended daily therapy of rifampicin (R), isoniazid (H), pyrazinamide (Z) and ethambutol (E) for 2 months followed by daily 4-month therapy of rifampicin (R) and isoniazid (H). Alternatively 2 months intensive phase of RHZE can be daily followed by alternate day combination phase (RH) of 4 months. Three weekly dosing throughout therapy (2RHZE, 4HR) can be given as DOTS provided every dose is directly observed and the patient is not HIV positive or living in an HIV prevalent setting [2].

The patient is first categorized to one of the treatment categories and is then given treatment as per guidelines for national programmes by WHO (Table 4). Genital TB is classified under category 1 being seriously ill extra pulmonary disease. To ensure quality-assured drugs in adequate doses, a full 6-month course pack box is booked for an individual patient in the DOTS center with fixed drug combipacks (FDC) of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol thrice a week for first 2 months (intensive phase) under direct observation followed by combination blister pack of isoniazid and rifampicin thrice a week for next 4 months (continuation phase).

Rarely FGTB cases can have relapse or failure categorizing them into category II (Table 4), which includes 2 months intramuscular injections of streptomycin thrice weekly along with other four drugs (SRHZE) of category I under direct supervision of DOTS center health worker for first 2 months followed by four drugs (RHZE) thrice a week for another month (intensive phase) followed by continuation phase with three drugs isoniazid (H), rifampicin (R) and ethambutol (E) thrice a week for another 5 months.

Non-DOTS Treatment

Patients not opting for DOTS treatment must take daily therapy of RHZE for 2 months (intensive phase) followed by RH for 4 months (continuation phase). Convenient and economic combipacks are available in market.

Treatment of Chronic Cases, Drug Resistant and Multidrug Resistant (MDR) FGTB

It is same as for pulmonary MDR with second-line drugs and is shown in Table 4 and is needed for long duration (18–24 months).

Monitoring

The women should be counseled about the importance of taking ATT regularly and consumption of good and nutritious diet and should report in case of any side effects of the drugs. Liver function test is no longer done regularly unless there are symptoms of hepatic toxicity. Similarly pyridoxine is not routinely prescribed with ATT unless there are symptoms of peripheral neuropathy with isoniazid. Rarely hepatitis can be caused by isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide, optic neuritis by ethambutol and auditory and vestibular toxicity by streptomycin in which case the opinion of an expert should be sought for restarting the ATT in a modified form.

Treatment of FGTB in HIV-Positive Women

HIV has had a disastrous impact on attempts to control as TB is a leading cause of HIV-related morbidity and mortality, while HIV is the most important factor for fuelling the TB epidemic in high HIV prevalence populations. In India, RNTCP and National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) have joined hands for better management of this dual epidemic. Possible options for antiretroviral therapy in TB patients include:

-

Defer antiretroviral therapy until TB treatment is completed

-

Defer antiretroviral therapy until the end of the initial phase of treatment and use ethambutol and isoniazid in the continuation phase

-

Treat TB with a rifampicin-containing regimen and use efavirenz + 2 NRTIs (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors)

-

Treat TB with a rifampicin-containing regimen and use 2 NRTIs and then change to a maximally suppressive HAART regimen on completion of TB treatment.

Surgical Treatment

The medical therapy, especially the modern short-course chemotherapy consisting of rifampicin and other drugs, is highly effective for the treatment of FGTB with rare need of surgery [8]. However, limited surgery like drainage from residual large pelvic or tubo-ovarian abscesses or pyosalpinx can be performed followed by ATT for better results as recommended by American Thoracic Society [8, 40].

There are much higher chances of complications during surgery in women with genital TB in hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, vaginal hysterectomy and laparotomy [35, 37, 42, 43]. There is excessive hemorrhage and nonavailability of surgical planes at time of laparotomy with higher risks of injury to the bowel and other pelvic and abdominal organs. In a case of abdomino-pelvic TB, bowel loops may be matted together with no plane between them and uterus and adnexa may be buried underneath the plastic adhesions and bowel loops and are inapproachable. Even trying to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy in such cases can cause injury to bowel necessitating a very difficult laparotomy and resection of injured bowel. It is better to take biopsies from the representative areas and close the abdomen without pelvic clearance in cases of laparotomy done for suspected pelvic tumors but found to be tubercular at laparotomy followed by full medical treatment.

Sometimes even after a full 6-month course of ATT, women with genital TB with infertility do not conceive when laparoscopy and hysteroscopy may be repeated to see any remaining disease. Outcome for fertility in FGTB is only good when ATT is started in early disease. However, cases of advanced TB with extensive adhesions in pelvis and uterus are usually untreatable with very poor prognosis for fertility. Tuboplasty performed after ATT does not help much with chances of flare-up of the disease and risk of ectopic pregnancy, should the women conceive [10, 44].

In Vitro Fertilization (IVF)

Most women with genital TB present with infertility and have poor prognosis for fertility in spite of ATT. The conception rate is low (19.2 %) with live birth rate being still low (7 %) in Tripathy and Tripathy series [10]. Parikh et al. [12] found IVF with ET to be the only hope for some of these women whose endometrium was not damaged with pregnancy rate of 16.6 % per transfer. Jindal [11] observed IVF–ET to be most successful out of all ART modalities in genital TB patients with 17.3 % conception rate in contrast to only 4.3 % with fertility enhancing surgery. Dam et al. [45] found latent genital TB responsible for repeated IVF failure in young Indian patients in Kolkata presenting with unexplained infertility with apparently normal pelvis and non-endometrial tubal factors. If after ATT their tubes are still damaged but their endometrium is receptive (no adhesions or mild adhesions which can be hysteroscopically resected), IVF–ET is recommended [8, 46]. However, if they have endometrial TB causing damage to the endometrium with shrunken small uterine cavity with Asherman’s syndrome, adoption or gestational surrogacy is advised to them [47].

New TB Research

There has been a renewed interest in research in TB at global level. New and improved BCG vaccines are being developed. New drugs, effective against strains that are resistant to conventional drugs and requiring a shorter treatment regimen, are being developed. Newer shorter (4–5 months) regime of ATT is being developed and studied [48]. By controlling TB, FGTB can also be kept at bay and treated early to prevent the development of short-term and long-term sequelae of this menace [8].

Key Points for Clinical Practice

-

1.

FGTB prevalence varies in different countries being much more common in developing countries, especially Africa and Asia, and is usually a secondary infection from lungs and other sites like abdomen.

-

2.

FGTB is responsible for up to 16 % cases of infertility in developing countries, while infertility is seen in up to 40–50 % cases of genital TB. Other main symptoms are menstrual dysfunction, especially oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain and vaginal discharge.

-

3.

High index of suspicion is required as many cases can be asymptomatic in early stages when it can be treated without causing significant damage to genital organs as untreated FGTB can cause permanent sterility through tubal damage and endometrial destruction (Asherman’s syndrome)

-

4.

Diagnosis is by good history taking, thorough clinical examination and judicious use of investigations, especially endometrial sampling for AFB culture, PCR and histopathological testing. Laparoscopy and hysteroscopy may be helpful in early diagnosis and to see the severity of disease for prognostication for fertility

-

5.

Medical treatment using DOTS strategy under direct observation and using quality-assured drugs in appropriate dosage and for adequate time is the main stay of treatment.

-

6.

Prognosis for fertility is poor. However, for tubal disease in the absence of endometrial disease, ART especially IVF–ET, may give some results. In cases of endometrial disease with shrunken cavity, prognosis for fertility is very poor even with IVF ET.

-

7.

Surgical treatment is rarely required and should only be done in exceptional circumstances and should be in the form of limited surgery like laparoscopy, hysteroscopy and drainage of abscess as surgery in genital and peritoneal TB can be difficult and hazardous.

-

8.

Treatment of TB in HIV-positive woman is same as in HIV-negative woman in consultation with experts in the field.

References

Dye C, Watt CJ, Bleed DM, et al. Evolution of tuberculosis control and prospects for reducing tuberculosis incidence, prevalence and deaths globally. JAMA. 2005;293:2790–3.

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control: a short update to the 2009 report. WHO/HTM/TB 2009, 426. Geneva: WHO; 2009.

WHO Report on the TB epidemic. TB a global emergency. WHO/TB/94.177. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994.

TB India 2014. Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) Status Report. Central TB Division, Directorate General of Health Services. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Nirman Bhavan, New Delhi, India. www.tbcindia.nic.in.

Kumar S. Female genital tuberculosis. In: Sharma SK, Mohan A, editors. tuberculosis. 3rd ed. Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publisher Ltd.; 2015. p. 311–24.

Neonakis IK, Spandidos DA, Petinaki E. Female genital tuberculosis: a review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43:564–72.

Schaefer G. Female genital tuberculosis. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1976;19:223–39. 1985; 237(suppl):197–200.

Sharma JB. Tuberculosis and obstetric and gynecological practice. In: Studd J, Tan SL, Chervenak FA, editors. Progress in obstetric and gynaecology, vol. 18. Philadephia: Elsevier; 2008. p. 395–427.

Oosthuizen AP, Wessels PH, Hefer JN. Tuberculosis of the female genital tract in patients attending an infertility clinic. S Afr Med J. 1990;77:562–4.

Tripathy SN, Tripathy SN. Infertility and pregnancy outcome in female genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2002;76:159–63.

Jindal UN. An algorithmic approach to female genital tuberculosis causing infertility. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:1045–50.

Parikh FR, Nadkarni SG, Kamat SA, et al. Genital tuberculosis—a major pelvic factor causing infertility in Indian women. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:497–500.

Gupta N, Sharma JB, Mittal S, et al. Genital tuberculosis in Indian infertility patients. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2007;97:135–8.

Singh N, Sumana G, Mittal S. Genital tuberculosis: a leading cause for infertility in women seeking assisted conception in North India. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:325–7.

Neonakis IK, Gitti Z, Krambovitis E, Spandidos DA. Molecular diagnostic tools in mycobacteriology. J Microbiol Methods. 2008;75:1–11.

Duggal S, Duggal N, Hans C, Mahajan RK. Female genital TB and HIV co-infection. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:361–3.

Sharma JB, Pushparaj M, Gupta N, et al. Genital tuberculosis: an important cause of Asherman’s syndrome in India. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277:37–41.

Sharma JB, Malhotra M, Pundir P, et al. Cervical tuberculosis masquerading as cervical carcinoma: a rare case. J Obstet Gynaecol Ind. 2001;51:184.

Sharma JB, Sharma K, Sarin U. Tuberculosis: a rare cause of rectovaginal fistula in a young girl. J Obstet Gynaecol Ind. 2001;51:176.

Sharma JB, Jain SK, Pushparaj M, et al. Abdomino-peritoneal tuberculosis masquerading as ovarian cancer: a retrospective study of 26 cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;282:643–8.

Koc S, Beydilli G, Tulunay G, et al. Peritoneal tuberculosis mimicking advanced ovarian cancer: a retrospective review of 22 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:565–9.

Dwivedi M, Misra SP, Misra V, et al. Value of adenosine deaminase estimation in the diagnosis of tuberculous ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1123–5.

Jeffry L, Kerrou K, Camatte S, et al. Peritoneal tuberculosis revealed by carcinomatosis on CT scan and uptake at FDG-PET. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;110:1129–31.

Sharma JB, Karmakar D, Kumar R, et al. Comparison of PET/CT with other imaging modalities in women with genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;118:123–8.

Sharma JB, Malhotra M, Arora R. Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome as a result of genital tuberculosis: a report of three cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:295–7.

Sharma JB, Roy KK, Gupta N, et al. High prevalence of Fitz-Hugh–Curtis Syndrome in genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2007;99:62–3.

Sharma S. Menstrual dysfunction in non-genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2002;79:245–7.

Malhotra N, Sharma V, Bahadur A, et al. The effect of tuberculosis on ovarian reserve among women undergoing IVF in India. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;117:40–4.

Sharma JB, Karmakar D, Hari S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings among women with tubercular tubo-ovarian masses. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;113:76–80.

Sharma JB, Pushparaj M, Roy KK, et al. Hysterosalpingographic findings in infertile women with genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2008;101:150–5.

Bhanu NV, Singh UB, Chakraborty M, et al. Improved diagnostic value of PCR in diagnosis of female genital tuberculosis leading to infertility. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:927–31.

Grosset J, Mouton Y. Is PCR a useful tool for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in 1995? Tubercl Lung Dis. 1995;76:183–4.

Jindal UN, Verma S, Bala Y. Favorable infertility outcomes following anti-tubercular treatment prescribed on the sole basis of a positive polymerase chain reaction test for endometrial tuberculosis. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1368–74.

Sharma JB, Roy KK, Pushparaj M, et al. Hysteroscopic findings in women with primary and secondary infertility due to genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;104:49–52.

Sharma JB, Roy KK, Pushparaj M, et al. Increased difficulties and complications encountered during hysteroscopy in women with genital tuberculosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:660–5.

Sharma JB, Roy KK, Pushparaj M, et al. Laparoscopic finding in female genital tuberculosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:359–64.

Sharma JB, Mohanraj P, Roy KK, et al. Increased complication rates associated with laparoscopic surgery among patients with genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2010;109:242–4.

Mittal S, Sharma JB. Dilemmas in diagnosis of female genital tuberculosis. In: Mukherjee GG, Tripathy SN, Tripathy SN, editors. Gential tuberculosis. 1st ed. Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd.; 2010. p. 83–91.

Arora R, Rajaram P, Oumachigui A, et al. Prospective analysis of short course chemotherapy in female genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1992;38:311–4.

American Thoracic Society. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America. Controlling tuberculosis in United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1169–227.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Tuberculosis. Clinical diagnosis and management of tuberculosis, and measures for its prevention and control. Clin Guidel 33. 2006. www.nice.org.uk/CGO33.

Sharma JB, Mohanraj P, Jain SK, et al. Increased complication rates in vaginal hysterectomy in genital tuberculosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:831–5.

Sharma JB, Mohanraj P, Jain SK, et al. Surgical complications during laparotomy in patients with abdominopelvic tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2010;110:157–8.

Sharma JB, Naha M, Kumar S, et al. Genital tuberculosis: an important cause of ectopic pregnancy in India. Indian J Tuberc. 2014;61(4):312–7.

Dam P, Shirazee HH, Goswami SK, et al. Role of latent genital tuberculosis in repeated IVF failure in Indian clinical settings. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61:223–7.

Malik S. IVF and tuberculosis. In: Mukherjee GG, Tripathy S, Tripathy SN, editors. Gential tuberculosis. 1st ed. Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd.; 2010. p. 135–40.

Samanta J, Goswami SK, Mukherjee GG, et al. Gestational surrogacy in gential tuberculosis. In: Mukherjee GG, Tripathy S, Tripathy SN, editors. gential tuberculosis. 1st ed. Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd.; 2000. p. 141–54.

Tripathy SN, Tripathy SN. Tuberculosis Manual for Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 1st ed. Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2015. p. 249–65.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful to Prof. Alka Kriplani, Prof. S Kumar, faculty and residents of Obstetrics and Gynecology at AIIMS, New Delhi, and Dr. Sangeeta Sharma (National Institute of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases, New Delhi, for their help in preparing this manuscript. I am also thankful to Sona Dharmendra, Senior Research Fellow (AIIMS), Dr Asmita (SRF, AIIMS) and Mr. Pawan Kumar for their help in data, typing and writing of manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, J.B. Current Diagnosis and Management of Female Genital Tuberculosis. J Obstet Gynecol India 65, 362–371 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-015-0780-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-015-0780-z