Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the laparoscopic findings in genital tuberculosis (TB).

Methods

A total of 85 women of genital TB, who underwent diagnostic laparoscopy for infertility or chronic pelvic pain were enrolled in this retrospective study conducted in our unit at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India from September 2004 to 2007.

Results

The mean age was 28.2 years and the mean parity was 0.24. Most women were from poor socioeconomic status (68.1%). Past history of TB was seen in 29 (34.1%) women with pulmonary TB in 19 (22.35%) women and extrpulmonary in 10 (11.7%) women. Most women presented with infertility (90.6% primary 72.9%; secondary 17.6%) while the rest had chronic pelvic pain (9.4%). The mean duration of infertility was 6.2 years. A total of 49 (57.6%) women had normal menses, while hypomenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, secondary amenorrhea and menorrhagia were seen in 25 (30.1%), 3 (3.5%), 5 (5.9%), and 2 (2.4%) women respectively. Diagnosis of genital TB was made by histopathological evidence of TB granuloma in 16 (18.8%) (Endometrial biopsy in 12.9%, laparoscopy biopsy in 5.9%) women, demonstration of acid fast bacilli (AFB) on microscopy in 2(2.3%), positive AFB culture in 2 (2.3%), positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in 55 (64.7%) and laparoscopic findings of genital TB in 40 (47.1%). The various findings on laparoscopy were tubercles on peritoneum (12.9%) or ovary (1.2%), tubovarian masses (7.1%), caseous nodules (5.8%), encysted ascitis in 7.1% women. Various grades of pelvic adhesions were seen in 56(65.8%) women. The various findings on fallopian tubes were normal looking tubes in (7.1%), inability to visualize in 12(14.1%), presence of tubercles on tubes in 3 (3.52%), caseous granuloma in 3 (3.52%), hydrosalpinx in 15 (17.6%) (Right tube 11.7%, left tube 5.9%), pyosalphinx in 3 (3.5%) on right tube and 2 (2.35%) in left tube, beaded tube in 3 (3.5%) on right tube, 4 (4.7%) in left tube with tobacco pouch appearance in 2 (2.35%) women. The right tube was patent in 9 (10.6%) while left tube was patent in 10(11.7%) cases only, while they were either not seen (absent in one case due to previous salphingectomy, inability to see due to adhesion in 14.12%) or blocked at various sites with cornual end being most common in 3 (3.5%) showing multiple block in right tube and 4.7% in left tube.

Conclusion

There is a significant pelvic morbidity and tubal damage in genital tuberculosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The world health organization (WHO) has declared tuberculosis a global emergency in 1994 as the disease affects about 8 million people each year causing 2 million deaths with majority of women hailing from developing countries [1, 2]. Female genital tuberculosis is a common disease in developing countries manifesting as infertility, menstrual dysfunction, chronic pelvic pain or abdominal pain with or without general symptoms like anorexia, weight loss and fever [3, 4]. Genital TB is almost always acquired from extra genital source like pulmonary or abdominal tuberculosis [5, 6]. Fallopian tubes are the most commonly involved genital organs followed by endometrium, ovary and rarely cervix, vagina and vulva [4, 6]. Genital tuberculosis is an important cause of infertility, especially in developing countries and can cause tubal blockage, peritubal, pelvic and abdominal adhesion [7–9], including perihepatic adhesions (Fitz-Hugh-Curtis Syndrome [10]). Genital TB can cause atrophy of endometrium causing Asherman syndrome and shrunken uterine cavity [11].

Diagnostic laparoscopy remains the mainstay in diagnosis of genital TB as many findings of genital TB like tubercles, adhesions, localized ascitis, caseation, etc. can be easily seen on laparoscopy and even a biopsy can be taken from representative area for histopathological examination. We present laparoscopic findings of 85 women diagnosed with genital TB on endometrial biopsy, laparoscopy or hysteroscopy.

Materials and methods

A total of 85 women, who underwent diagnostic laparoscopy as a part of diagnostic modality for infertility or chronic pelvic pain and who were found to have genital tuberculosis were enrolled in this retrospective study, conducted over the last 3 years from September 2004 to 2007 in authors unit, at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. As it was a retrospective study, ethical clearance was not necessary. Detailed history like fever, weight loss, anorexia, menstrual dysfunction, infertility including history of tuberculosis in family members or close contacts and any past history of tuberculosis or antituberculous therapy was taken from all women. Clinical examination, lymphadenopathy, respiratory, cardiac, abdominal examination, speculum and bimanual examination were done in all women. All women underwent investigations like complete haemogram, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), mantoux test, urine examination, blood sugar, investigation for infertility i.e. husband semen analysis, serum follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and leutenizing hormone (LH). Ultrasound or CT scan of pelvis was performed in indicated cases. Endometrial biopsy was performed in all cases and the sample was sent for acid fast bacilli (AFB) demonstration of microscopy, AFB culture, histopathology for status of endometrium and any tuberculous granuloma and for polymerase chain reaction. As regards women reluctant to undergo endometrial biopsy, menstrual blood was sent for AFB culture and PCR.

All women suspected to have genital TB were subjected to laparoscopy with or without hysteroscopy. Detailed laparoscopic examination was performed and pelvic cavity was carefully examined for evidence of genital TB like tubercles, caseation, congestion, edema, adhesion in pelvic organs, multiple fluid filled pockets, condition of fallopian tube, any hydrosalpinx, pyosalphinx, tubovarian masses, any pelvic adhesion with their severity and grading. Biopsy from suspicious areas was taken in selected cases. The details of perihepatic adhesions were also noted whenever available in notes. Diagnosis of female genital TB was made by demonstration of AFB on microscopy, AFB culture, PCR or on laparoscopic findings.

All women diagnosed with female genital TB were given antitubercular therapy as per world health organization’s Directly Observed Treatment Short course (DOTS) strategy, as per revised national tuberculosis control programme (RNTCP) of India guideline using Isoniazid, Rifampicin, Ethambutol and Pyrazamide for 2 months, followed by Isoniazid and Rifampicin for next 4 months [11, 12]. The drugs were supplied free of cost from DOTS centre. All women were regularly followed up to ensure compliance. Routine Pyridoxine was not given and liver function tests were only performed if there was clinical suspicion of hepatitis.

Only those women who had positive evidence of female genital TB, and underwent diagnostic laparoscopy were enrolled in this retrospective study to observe the findings of genital TB on laparoscopy. Data was analyzed and suitable statistical analysis was performed using Fisher exact chi square test with p-value ≤ 0.05 taken as significant.

Results

The characteristics of the women are shown in Table 1. As per Kuppuswami classification [13] majority of women were from poor socioeconomic status. Past history of TB could be obtained in 29 (34.1%) women.

The various symptoms of women are shown in Table 2. Most women had normal periods or hypomenorrhea. Majority of women had infertility as the main symptom.

Mode of diagnosis of genital TB is shown in Table 3. Positive polymerase chain reaction was the commonest finding (64.7%) women, while definitive laparoscopic findings of TB were observed in 47% women.

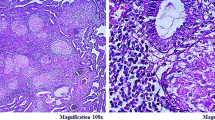

The various laparoscopic findings in fallopian tubes in genital TB are shown in Table 4. In 12 cases the pelvis was not assessed due to inability to visualize the tubes due to dense adhesions. Right tube was absent in one case due to prior salpingectomy. The right tube and left tube alone could be seen in two cases each due to adhesion in the pelvis. Most women had abnormalities in the fallopian tube. The various abnormalities observed were tubercles, caseous granuloma, hydrosalphinx (Figs. 1, 3); pyosalphinx, and tobacco-pouch appearance.

Tubal patency was not done in all cases. In many cases pelvis was not visualized due to adhesion. Few patients had caseation and pyosalpinx chromotubation was not done due fear of flare up. For some patient laparoscope was done for chronic pelvic pain where infertility was not a concern. In the remaining cases the tubes were assessed. As shown in Table 4, the tubes were blocked in majority 61.7% with many having cornual block (21%).

Laparoscopic pelvic and abdominal findings in genital TB are shown in Table 5. As it was a retrospective study, record of upper abdomen was found in only 25 women. The various pelvic findings were tubovarian masses, tubercles and caseous nodule on peritoneum and ovary shown in Fig. 5. Encysted ascitis with pocket-filled cavities were also observed. The various grades of pelvic adhesion that were seen were grade I (mild pelvic adhesion), grade 2 shown in Fig. 4, grade 3 (completely obliteration of pelvis) and grade 4 in Fig. 2 (abdominal and pelvic ). Perihepatic adhesions (Fitz-Hugh-Curtis-Syndrome) were seen in 10 out of 25 cases. Where they were looked for, as they were not seen in rest of the cases by the doctor performing laparoscopy. Many women had more than one abnormality. All women were given ATT under RNTCP control using DOTS Strategy.

Discussion

Female genital tuberculosis is a common disease in developing countries causing menstrual irregularities, infertility, chronic pelvic pain and is almost always secondary to pulmonary or abdominal TB [1, 2, 4]. It usually affects women of reproductive age group with mean age being 28.2 [4] and was 28.1 years in our study. Primary infection of female genital organ is usually haematogenous and is rarely from sexual transmission with mycobacterium tuberculosis hominis causing majority of infection.

Prevalence of female genital TB varies from 1 to 19% depending on the country [14]. It is becoming a major health problem through the world including western world due to co infection with human immunodeficiency virus(HIV) which significantly increases the risk of developing TB, more liberal immigration from high risk to low risk areas and emergence of multidrug resistant (MDR) and extremely drug resistant (XDR) TB [1, 15]. It is an important cause of infertility, especially in less developed countries [7, 16]. Diagnosis of female genital TB can be difficult as it is a paucibacillary disease and a high index of suspicion is required. The diagnostic dilemma arises due to varied clinical presentation, diverse results on imaging and endoscopy and availability of battery of bacteriological, serological and histopathological investigations which are often required to obtain a collective diagnosis of TB [4]. Family history of TB or ATT, detailed history, general physical examination, abdominal and gynecological examination and judicious use of various diagnostic modalities are required to make a correct and timely diagnosis for timely and appropriate treatment. Although demonstration of AFB on microscopy or culture or histopathological evidence of TB granuloma gives definitive diagnosis, they are positive in limited cases only making it necessary to use additional modalities like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), hysteroscopy or laparoscopy findings to make timely diagnosis for early treatment [17]. Hysterosalpingography (HSG) is usually avoided in genital TB for fear of flare up of disease, but often done in unsuspected cases gives important clues in diagnosis by demonstrating abnormal HSG findings like shrunken or irregular uterine cavity or abnormalities of fallopian tube like hydrosalpinx, beading, tobacco-pouch appearance, blocked tubes, venous and lymphatic intravasation of dye [18]. In such cases, diagnosis should be further confirmed by other tests like endometrial sampling, hysteroscopy or laparoscopy.

Laparoscopy is the most reliable tool to diagnose genital TB, especially for tubal, ovarian and peritoneal disease [7, 19]. It can be combined with hysteroscopy for maximum information and can show morphological abnormalities of the fallopian tube directly. The various laparoscopic findings observed by different authors can be tubercles on tube or peritoneum, caseation or granuloma, beaded tube, blocked tube, adhesions, hydrosalpinx, tubo-ovarian masses, encysted effusion [3, 7, 19–22]. In the subacute stage, there may be congestion, edema and adhesion in pelvic organ with multiple fluid filled pockets. There are military tubercles, white, yellow and opaque plaques over fallopian tubes and uterus. In the chronic stage, there may be yellow small nodules on tubes (nodular salpingitis), short swollen tubes with agglutinated fimbria (patchy salpingitis), unilateral or bilateral hydrosalpinx, pyosalpinx or caseosalpinx with various types of adhesions which may be localized to the pelvis or may spread to abdomen and even in liver areas [9]. Various other abnormalities could be granuloma, plaques, exudates, tub ovarian masses or pelvic congestion.

We observed tubercles on peritoneum in 15.9% cases, tubo-ovarian masses in 26%, caseous nodules in 7.2%, encysted ascitis in 8.7% and various grades of pelvic adhesion in 65.8% cases. The various abnormalities of fallopian tube were hydrosalpinx (21.7%), pyosalpinx (2.9%), beaded tubes (10.1%) and tobacco-pouch appearance (2.9%). Most women had blocked fallopian tubes or there was inability to see tubes due to adhesions (14.2%). Our results confirm that female genital TB is rampant in India and especially in infertile women (90.6%) and causes significant morbidity and damage to endometrium and fallopian tubes making very poor prognosis for fertility. Our study highlights the need to keep diagnosis of genital TB always in mind, diagnose it in early stage and give timely and appropriate treatment using DOTS strategy for better outcome. Using an algorithm for accurate diagnosis of female genital TB by combining history taking, examination and investigations is helpful in early stages [20, 23]. Use of short-course chemotherapy is strongly recommended for better outcome as has been the experience of various authors and RNTCP of India [12, 24].

References

WHO Report on the TB epidemic (1994) TB a global emergency, WHO/TB/ 94.177. World Health Organization, Geneva

Dye C, Watt CJ, Bleed DM, Hosseini SM, Raviglione MC (2005) Evolution of tuberculosis control and prospects for reducing tuberculosis incidence, prevalance and deaths globally. JAMA 293:2790–2793

Parikh FR, Nadkarni SG, Kamat SA, Naik N, Soonawala SB, Parikh RM (1997) Genital tuberculosis––a major pelvic factor causing infertility in Indian women. Fertil Steril 67:497–500

Sutherland AM (1983) The changing pattern of tuberculosis of the female genital tract: a thirty-year survey. Arch Gynaecol 234:95–101

Bazaz-Malik G, Maheshwari B, Lal N (1983) Tuberculosis endometritis: a clinicopathologic study of 1000 cases. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 90:84–86

Schaefer G (1976) Female genital tuberculosis. Clin Obstet Gynaecol 19:223–239

Gupta N, Sharma JB, Mittal S, Singh N, Misra R, Kukereja M (2007) Genital tuberculosis in Indian infertility patients. Int J Gynecol Obstet 97(2):135–138 (Epub 2007 Mar 23)

Sharma JB, Pushparaj M, Gupta N, Roy KK, Kumar S, Malhotra N, Mittal S. Genital tuberculosis: an important cause of Ashermans’ syndrome in India. Arch Gynecol Obstet (Epub ahead of print)

Sharma JB, Malhotra M, Arora R (2003) Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome as a result of genital tuberculosis: a report of three cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 82(3):295–297

Deshmukh KK, Lopez JA, Naidu TAK, Gaurkhede MD, Kashbhawala MV (1985) Place of laparoscopy in pelvic tuberculosis in infertile women. Arch Gynecol 237(Suppl):197

World health Organization (2003) Treatment of tuberculosis. Guidelines for national programmes, 3rd edn. WHO, Geneva (WHO/CDS/TB/2003.313)

TB India (2006) Revised National Tuberculosis control Programme (RNTCP) status Report. Central TB division, directorate General of Health Services. Ministry of Health and family Welfare. Nirman Bhavan, New delhi. http://www.tbcindia.org

Mishra D, Singh HP (2003) Kuppuswami’s socioeconomic status scale: A Revision. Indian J Pediatr 70:273–274

Varma TR (1991) Genital tuberculosis and subsequent fertility. Int J Gynecol Obstet 35:1–11

Wise GJ, Marella V (2003) Genitourinary manifestations of tuberculosis. Urol Clin North Am 30(1):111–121

Tripathy SN, tripathySN (1990) Laparoscopic observation of pelvic organs in pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet 32:129–131

Bhanu NV, Singh UB, Chakraborty M et al (2005) Improved diagnostic value of PCR in diagnosis of female genital tuberculosis leading to infertility. J Med Microbiol 54:927–931

Sharma JB, Pushparaj M, Roy KK, Neyaz Z, Gupta N, Kumar S, Mittal S. Hysterosalpingographic findings in infertility with genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet (in press)

Bhide AG, Parulekar SV, Bhattacharya MS (1987) Genital tuberculosis in females. J Obstet Gynaecol India 37:576–578

Jindal UN (2006) An algorithmic approach to female genital tuberculosis causing infertility. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 10:1045–1050

Kumari C, Sinha S (2000) Laparoscopic evaluation or tubal factors in cases of infertility. J Obstet Gynaecol India 50:67–70

Rozati R, Sreenivasagari R, Rajeshwari CN (2006) Evaluation of women with infertility and genital tuberculosis. J Obstet Gynaecol India 56:423–426

Katoch VM (2004) Newer diagnostic techniques for tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res 120:418–428

Arora R, Rajaram P, Oumachiqui A, Arora VK (1992) Prospective analysis of short course chemotherapy in female genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 38:311–314

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, J.B., Roy, K.K., Pushparaj, M. et al. Laparoscopic findings in female genital tuberculosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 278, 359–364 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-008-0586-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-008-0586-7