Abstract

This study investigated the association between congregational relationships and personal and collective self-esteem among young Muslim American adults. Mosque-based emotional support and negative interactions with congregants were assessed in relation to personal and collective self-esteem. Data analysis was based on a sample of 231 respondents residing in southeast Michigan. Results indicated that receiving emotional support from congregants was associated with higher levels of collective self-esteem but was unassociated with personal self-esteem. Negative interaction with congregants was associated with personal self-esteem. Together, these findings indicate that mosque-based emotional support and negative interactions function differently for personal and collective self-esteem, which provides evidence that although personal and collective self-esteem are interrelated constructs, they are also conceptually discrete aspects self-evaluations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The purpose of this study is to investigate the association between mosque-based social relationships and personal and collective self-esteem, two distinct facets of a person’s self-concept. A person’s self-concept is comprised of a personal aspect and a social aspect. The personal aspect of one’s self-concept is derived from personal attributes and beliefs, while the social aspect of one’s self-concept is derived from attributes of social groups to which one belongs. Social Identity Theory (Tajfel and Turner 1985) focuses on the social aspect of the self-concept, referred to as social identity, group identity, or collective identity, to explain intergroup behaviors, such as in-group bias. According to Tajfel and Turner, collective identity is one’s self-concept that is derived from membership in social groups, such as race, gender, ethnicity, and nationality. In order to collectively identify with a particular social group, the person must merely perceive themselves as a member of the group; thus, collective identity deals with the perception of belonging to a social group rather than categorical membership within a social group. This theory assumes that intergroup discrimination and biases that favor one’s own social groups stems from motivations to maintain or enhance one’s positive collective identity.

Luhtanen and Crocker (1992) extended the Social Identity Theory by introducing the concept of collective self-esteem. They hypothesized that intergroup discrimination and biases serve to enhance one’s collective self-esteem. Collective self-esteem is an indicator of the positive evaluation of one’s collective identity (Luhtanen and Crocker 1992). In other words, collective self-esteem refers to the value one places on the social groups to which one belongs. This is contrasted with personal self-esteem, which is one’s evaluation of one’s own worth based on one’s personal identity and attributes, such as one’s skills and qualities. Although collective and personal self-esteem are interrelated, they are not strongly correlated, indicating that they are distinct constructs that both contribute to a person’s sense of self-concept and self-worth (Luhtanen and Crocker 1992; Verkuyten and Masson 1995).

Luhtanen and Crocker (1992) posited that collective self-esteem is comprised of four distinct dimensions—membership self-esteem, private collective self-esteem, public collective self-esteem, and importance of identity. The membership self-esteem dimension refers to one’s judgment of how good or worthy one is as a member of a social group. Private collective self-esteem is one’s evaluation of the worth of the social group to which one belongs. In contrast, public collective self-esteem is one’s evaluation of how other individuals would evaluate one’s social group. Importance of identity is one’s judgment of how important one’s social group membership is to one’s self-concept. Empirical work on self-esteem tends to be heavily biased toward personal self-esteem with few studies examining collective self-esteem. Thus, our understanding of evaluations of self is mostly limited to evaluations of self based on the individualistic aspects of the self-concept, and little is known about evaluations of self based on the group-oriented aspects of the self-concept.

The main focus of collective self-esteem research has been on behavioral and mental health outcomes associated with collective self-esteem (e.g., Crocker et al. 1994; Barker 2009; Butler and Constantine 2005; Yeh 2002). Few studies have investigated factors that predict collective self-esteem. However, some studies on personal self-esteem have found that informal social support, a major function of social relationships, is predictive of higher levels of personal self-esteem (Nguyen et al. 2016b; Pinquart and Sörensen 2000). Generally, evidence suggests that social support is associated with multiple facets of psychological well-being, including life satisfaction, happiness, and self-esteem (Diener and Diener 2009; Karademas 2006; Lincoln 2000; Pinquart and Sörensen 2000; Symister and Friend 2003). For instance, Pinquart and Sörensen’s (2000) meta-analysis of studies on social support and psychological well-being among older adults found that research in this area indicates that higher levels of support is predictive of higher levels of life satisfaction, happiness, and self-esteem. Similarly, Nguyen et al.’s (2016a, b) investigation of the link between social support from extended family and friends and psychological well-being in a nationally representative sample of older African Americans found that respondents who reported higher levels of support from extended family members and friends also reported higher levels of self-esteem, life satisfaction, and happiness.

Church-based social support is supportive exchanges between members of a congregation. This type of support is distinct from other types of support such as family and friendship support, as church-based support is a social resource that is available exclusively to individuals who are socially embedded within a religious community, and the shared values, beliefs, and norms within this community enhance a sense of the group collective, which reinforces members’ religious identity (Holt et al. 2012). Research on church-based support indicates that it is predictive of mental health and well-being. Empirical studies in this area have found that church-based support protects against a range of mental health problems, such as anxiety (Graham and Roemer 2012), suicidal ideation (Chatters et al. 2011), depressed affect (Krause et al. 1998; Krause and Wulff 2005), depressive symptoms (Chatters et al. 2015), and serious psychological distress (Chatters et al. 2015) and is predictive of greater life satisfaction (Krause 2004; Lim and Putnam 2010). Chatters et al.’s (2015) investigation of informal support and mental health among older African Americans found that respondents who reported receiving more support from church members reported lower levels of depressive symptoms and serious psychological distress, even in the presence of support from family members. This demonstrates church-based support’s unique contribution to mental health and psychological well-being.

In contrast to studies of church-based social support, little is known about congregational support among Muslim Americans, or mosque-based social support. Mosques are not only religious institutions for Muslim Americans, but they also represent important cultural, civic, and social institutions for this population. For instance, mosques in the USA serve as places for social gatherings, community and political involvement, community resources (i.e., legal, financial, social, cultural), social services, and education (Ghanea Bassiri 2010; Leonard 2003; McCloud 2006; Smith 1999). Many mosques in the USA offer full-time and weekend Islamic schools, Islamic study classes, khatirah (short lectures), Arabic classes, sisters’ (women only) activities or programs, Qur’an memorization or tajwid classes, youth activities or programs, classes for recently converted Muslims, fitness and martial arts classes and sports team (Bagby et al. 2001). Moreover, mosques often engage in political and community activities and provide social services to members of the local community, including cash assistance for families and individuals, marital and family counseling, prison and jail programs, food pantry, soup kitchen, tutoring and literacy programs, thrift store, and clothes collection for the poor (Bagby et al. 2001). Additionally, many mosques in the USA partially function as community centers for local Muslim populations (Bagby et al. 2001).

Research on mosque-based support among Muslim Americans has found that women tend to more frequently receive social support from fellow congregants (Nguyen et al. 2013). Individuals who attend mosque frequently and individuals who are more involved within their congregations are also more likely to receive support from congregants (Nguyen et al. 2013). In contrast, education is negatively associated with mosque-based support (Nguyen et al. 2013); more highly educated individuals are less likely to receive support. Similarly, Asians congregants are less likely to receive support from fellow congregants as compared to Arab congregants (Nguyen et al. 2013).

Negative interactions, which include conflicts, criticisms, and excessive demands, are another aspect of social relationships that are perceived and reacted to as stressors. Consequently, negative interactions can erode one’s sense of self-worth and competence and interfere with the individual’s ability to use cognitive and social resources to effectively manage stressors (Krause 2005; Rook 1984). They represent a combination of mechanisms and processes that have potential adverse effects on mental and physical health. Growing evidence points to negative interactions as a risk factor for mental and physical illness (King et al. 2002; Newsom et al. 2003; Seeman and Chen 2002; Tanne et al. 2004), and its effects on mental and physical health is especially pernicious, as negative interactions tend to persist over time (Bolger et al. 1989). For example, studies have linked negative interactions to suicidality (Lincoln et al. 2012), depressive symptoms (Chatters et al. 2015), psychological distress (Chatters et al. 2015), social anxiety disorder (Levine et al. 2015), and posttraumatic stress disorder (Nguyen et al. 2016a).

Focus of the Present Study

Of the few studies that have examined collective self-esteem, most have focused on collective self-esteem in specific racial and ethnic groups. For example, studies have investigated collective self-esteem among African American adolescents (Constantine et al. 2002), Asian American (Kim and Omizo 2005), Vietnamese American (Lam 2007), African American (Constantine et al. 2002), and Latino (Constantine et al. 2002) college students, and Indian nationals (Khare et al. 2012). However, collective self-esteem has yet to be explored in relation to religious groups and identities. Social identities based on religious affiliations are a unique subset of social identities because they are inextricably linked to a religious belief system. That is, individuals within a religious group share, to a certain extent, a set of values and beliefs based on common faith and religious teachings. Despite the importance of religious affiliation as a category of social identity, no studies have investigated collective self-esteem relative to religious affiliation.

The purpose of the present investigation is to examine the association between mosque-based social relationships and personal and collective self-esteem of young Muslim American adults (i.e., Muslim Americans’ evaluation of Muslims as a social group). Based on prior research on social support and personal self-esteem, I expect that mosque-based social support (i.e., informal support exchanged between congregants of a mosque) will be positively associated with both personal and collective self-esteem among young Muslim American adults. Moreover, I expect that negative interactions with congregants will be negatively associated with both personal and collective self-esteem.

Methods

Data

Analysis was conducted on a sample of 231 Muslim respondents, who were community members in the Dearborn, Michigan area and undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Michigan’s Ann Arbor and Dearborn campuses, which have relatively large Muslim student bodies. Participants were recruited through the psychology departments’ subject pools as well as through undergraduate and graduate courses, fliers posted around the campus, and student organizations on campus. Subject pool respondents, psychology students, and marketing students completed the survey in exchange for partial course credit. Community members were recruited through local mosques and Muslim organizations in the Dearborn area. The study period began in the summer of 2009 and ended in the summer of 2010.

Measures

Independent Variables

Mosque-based emotional support was measured using a two-item index. Respondents were asked, “How often do the people in your congregation: (1) make you feel loved and cared for and (2) listen to you talk about your private problems and concerns?” Negative interaction with congregants was assessed with a two-item index asking, “How often do the people in your congregation make too many demands on you” and “How often are the people in your congregation critical of you and the things you do?” The response scale for these two indices ranged from 1 “never” to 4 “very often.” These mosque-based emotional support and negative interaction measures were based on the short form of the religious support indices developed by the Fetzer Institute and National Institute on Aging (Fetzer 1999). Each of the two items for the emotional support and negative interaction indices were averaged to derive separate scores for emotional support and negative interaction. The Cronbach’s alphas for the emotional support and negative interactions indices are .78 and .79, respectively.

Dependent Variables

Collective self-esteem was measured using an adaptation of Luhtanen and Crocker’s Collective Self-Esteem Scale (Luhtanen and Crocker 1992); the scale in the current study was adapted to measure respondents’ evaluation of their membership in the Muslim religious group. This scale consisted of 16 items, which assessed membership self-esteem, private collective self-esteem, public collective self-esteem, and importance of identity. Responses were based on a 7-point Likert-type scale, with response categories ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree.” Negative valence items were reverse-coded and included in the computation of the scale average, which represented a collective self-esteem score (Cronbach’s alpha = .89). Personal self-esteem was assessed using the 16-item Self-Liking Self-Competence Scale (Tafarodi and Swann 1995). The response categories for this scale ranged from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree.” Negative valence items were reverse-scored. The personal self-esteem score was derived from the average of the 16 items (Cronbach’s alpha = .89).

Control Variables

The multivariate analysis controlled for race/ethnicity, age, gender, and nativity. Race/ethnicity differentiated between Arab, Asian, white, and other. Gender was coded as 0 for male and 1 for female. Age was measured as a continuous variable. Respondents’ educational attainment differentiated between respondents who had a high school education or less, some college, and bachelor’s degree or higher. Nativity assessed whether respondents were born within the USA or in another country.

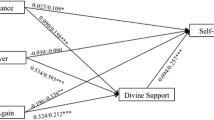

Analysis Strategy

OLS regression analysis was performed to test the effects of mosque-based emotional support and negative interaction with congregants on personal and collective self-esteem. All regression analyses controlled for race, age, gender, educational attainment, and nativity.

Results

Table 1 presents selected characteristics of the sample. The average age of the sample was 22 years. Women comprised slightly over half of the sample (58%). The majority of respondents identified as Arab (55%); Asian respondents comprised the second largest race/ethnic group (23%). The majority of respondents reported having some college education (65%). More than half of respondents were born in the USA (57%). Overall, respondents reported receiving moderate levels of emotional support from congregants and infrequent negative interaction with congregants. Respondents reported moderate to high levels of collective and personal self-esteem.

Findings for the multivariate analysis, presented in Table 2, indicated that mosque-based emotional support was not associated with personal self-esteem (Model 1). However, negative interaction with congregants was associated with lower personal self-esteem. With regard to collective self-esteem, mosque-based emotional support was positively associated with collective self-esteem (Model 2). That is, respondents who reported receiving more support from congregants also reported more positive evaluations of Muslims, as a religious group. On the other hand, negative interaction was negatively associated with collective self-esteem, with respondents who experienced more frequent negative interaction reporting less positive evaluations of Muslims.

Discussion

Although an empirical body of evidence indicates that informal social support is predictive of higher levels of personal self-esteem, there is no information on the effects of social support on collective self-esteem. Collective self-esteem is distinct from personal self-esteem in that it is a person’s evaluation of the worth of the social groups to which they belong rather their evaluation of their personal worth. Consequently, we do not know whether social support operates similarly to personal self-esteem in bolstering one’s sense of worth for the social groups to which one belongs. To address this gap in knowledge, the current study focused on collective self-esteem, as well as personal self-esteem, among young Muslim American adults and shed light on the association between mosque-based emotional support and negative interaction and collective and personal self-esteem in this underresearched population.

The data indicated that mosque-based emotional support bolstered respondents’ collective self-esteem but not personal self-esteem. That is, receiving emotional support from fellow congregants benefited Muslim Americans’ perception of their religious group, but did not benefit their perceptions of their own personal worth. This is not surprising given that those providing support to respondents also belong to the same religious groups. Thus, the provision of support, which is likely to be perceived as a positive act, by individuals who heuristically represent the respondents’ religious group is likely to positively shape their evaluations of their religious group. In explanation of why support from congregants had no effect on personal self-esteem, it is possible that respondents were receiving support from other sources, such as family members and friends, that have greater effects on bolstering the respondents’ sense of self-worth and nullify the effects for support from congregants.

With respect to negative interactions, the data revealed that respondents who reported more frequent negative interactions with congregants also reported lower personal self-esteem. This is consistent with evidence from the literature, which has found that negative interactions are predictive of a decreased sense of self-worth and self-efficacy (Lincoln 2000). Because negative interactions involve evaluative information about the person, they call into question and threaten positive evaluations of self and erode one’s perceptions as being competent, efficacious, and having self-worth and self-esteem (Lincoln 2000).

Several key limitations in this study should be noted. This study is based on a non- probability, convenience sample of young adults; the mean age of respondents in this study is younger than the general USA and Muslim American populations. Moreover, a large proportion of this sample consisted of college students. For reason of convenience, college students may be more likely to attend Jumu’ah service organized by a Muslim student organization on campus with other students rather than at a local community mosque, especially at colleges where there are no mosques within walking distance of campus. Jumu’ah service on college campuses may be qualitatively different from service held at a local mosque with respect to organization and attendees’ experiences. Together, these factors may restrict the representativeness of this sample and the generalizability of study findings. The cross-sectional design of this study presents a second limitation to the current analysis. Cross-sectional designs do not permit for causal inferences, so it is not possible to determine whether receiving emotional support from congregants leads to more positive regard for respondents’ own religious group or vice versa. Similarly, with cross-sectional data, it is not possible to determine whether negative interaction with congregants leads respondents to develop more negative perceptions of themselves or vice versa.

Despite these limitations, this study is the first to examine collective self-esteem among young Muslim American adults, and is one of the very few studies to investigate congregation-based support networks in this population and provides an initial exploration of the role of religion and religious networks in the psychological well-being of a large but understudied population in the USA. Future research on collective and personal self-esteem among Muslim Americans should consider other sources of support and negative interaction, such as extended family, friends, neighbors, and co-workers. Understanding the unique contributions of each of these groups to the psychological well-being of Muslim Americans provides useful information on the functions of different types of relationships in this population and can inform social support interventions.

References

Bagby, I. A. W., Perl, P. M., & Froehle, B. (2001). The mosque in America: A national portrait: A report from the mosque study project. Washington, D.C.: Council on American-Islamic Relations.

Barker, V. (2009). Older adolescents’ motivations for social network site use: The influence of gender, group identity, and collective self-esteem. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12(2), 209–213.

Bolger, N., DeLongis, A., Kessler, R. C., & Schilling, E. A. (1989). Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 808–818.

Butler, S., & Constantine, M. (2005). Collective self-esteem and burnout in professional school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 9(1), 55–62.

Chatters, L. M., Taylor, R. J., Lincoln, K. D., Nguyen, A., & Joe, S. (2011). Church-based social support and suicidality among African Americans and black Caribbeans. Archives of Suicide Research, 15(4), 337–353. doi:10.1080/13811118.2011.615703.

Chatters, L. M., Taylor, R. J., Woodward, A. T., & Nicklett, E. J. (2015). Social support from church and family members and depressive symptoms among older African Americans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(6), 559–567. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2014.04.008.

Constantine, M. G., Robinson, J. S., Wilton, L., & Caldwell, L. D. (2002). Collective self-esteem and perceived social support as predictors of cultural congruity among black and Latino college students. Journal of College Student Development, 43(3), 307–316.

Crocker, J., Luhtanen, R., Blaine, B., & Broadnax, S. (1994). Collective self-esteem and psychological well-being among white, black, and Asian college students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 503–513.

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (2009). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem Culture and well-being (pp. 71–91). Berlin: Springer.

Fetzer, I. (1999). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use on health research: A report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Kalamazoo, MI: John E. Fetzer Institute.

Ghanea Bassiri, K. (2010). A history of Islam in America: From the new world to the new world order. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Graham, J. R., & Roemer, L. (2012). A preliminary study of the moderating role of church-based social support in the relationship between racist experiences and general anxiety symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(3), 268–276.

Holt, C. L., Schulz, E., Williams, B., Clark, E. M., Wang, M. Q., & Southward, P. L. (2012). Assessment of religious and spiritual capital in African American communities. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(4), 1061–1074.

Karademas, E. C. (2006). Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: The mediating role of optimism. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(6), 1281–1290.

Khare, A., Mishra, A., & Parveen, C. (2012). Influence of collective self esteem on fashion clothing involvement among Indian women. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 16(1), 42–63.

Kim, B. S. K., & Omizo, M. M. (2005). Asian and European American cultural values, collective self-esteem, acculturative stress, cognitive flexibility, and general self-efficacy among Asian American College Students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(3), 412–419.

King, A. C., Atienza, A., Castro, C., & Collins, R. (2002). Physiological and affective responses to family caregiving in the natural setting in wives versus daughters. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 9(3), 176–194.

Krause, N. (2004). Common facets of religion, unique facets of religion, and life satisfaction among older African Americans. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59(2), S109–S117.

Krause, N. (2005). Negative interaction and heart disease in late life: Exploring variations by socioeconomic status. Journal of Aging and Health, 17(1), 28–55.

Krause, N., Ellison, C. G., & Wulff, K. M. (1998). Church-based emotional support, negative interaction, and psychological well-being: Findings from a national sample of Presbyterians. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37(4), 725–741. doi:10.2307/1388153.

Krause, N., & Wulff, K. M. (2005). Friendship ties in the church and depressive symptoms: Exploring variations by age. Review of Religious Research, 46(4), 325–340.

Lam, B. T. (2007). Impact of perceived racial discrimination and collective self-esteem on psychological distress among Vietnamese-American college students: Sense of coherence as mediator. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(3), 370–376.

Leonard, K. I. (2003). Muslims in the United States: The state of research. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications.

Levine, D. S., Taylor, R. J., Nguyen, A. W., Chatters, L. M., & Himle, J. A. (2015). Family and friendship informal support networks and social anxiety disorder among African Americans and black Caribbeans. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(7), 1121–1133. doi:10.1007/s00127-015-1023-4.

Lim, C., & Putnam, R. D. (2010). Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. American Sociological Review, 75(6), 914–933. doi:10.1177/0003122410386686.

Lincoln, K. D. (2000). Social support, negative social interactions, and psychological well-being. Social Service Review, 74(2), 231–252. doi:10.1086/514478.

Lincoln, K. D., Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., & Joe, S. (2012). Suicide, negative interaction and emotional support among black Americans. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(12), 1947–1958. doi:10.1007/s00127-012-0512-y.

Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1992). A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(3), 302–318.

McCloud, A. B. (2006). Transnational Muslims in American society. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Newsom, J. T., Nishishiba, M., Morgan, D. L., & Rook, K. S. (2003). The relative importance of three domains of positive and negative social exchanges: A longitudinal model with comparable measures. Psychology and Aging, 18(4), 746–754.

Nguyen, A. W., Chatters, L. M., Taylor, R. J., Levine, D. S., & Himle, J. A. (2016a). Family, friends, and 12-month PTSD among African Americans. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51, 1149–1157. doi:10.1007/s00127-016-1239-y.

Nguyen, A. W., Chatters, L. M., Taylor, R. J., & Mouzon, D. M. (2016b). Social support from family and friends and subjective well-being of older African Americans. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(3), 959–979. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9626-8.

Nguyen, A. W., Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., Ahuvia, A., Izberk-Bilgin, E., & Lee, F. (2013). Mosque-based emotional support among young muslim Americans. Review of Religious Research, 55(4), 535–555. doi:10.1007/s13644-013-0119-0.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2000). Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 15(2), 187–224.

Rook, K. S. (1984). The negative side of social interaction: impact on psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(5), 1097–1108.

Seeman, T., & Chen, X. (2002). Risk and protective factors for physical functioning in older adults with and without chronic conditions: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(3), S135–S144.

Smith, J. I. (1999). Islam in America. New York: Columbia University Press.

Symister, P., & Friend, R. (2003). The influence of social support and problematic support on optimism and depression in chronic illness: A prospective study evaluating self-esteem as a mediator. Health Psychology, 22(2), 123–129.

Tafarodi, R. W., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (1995). Self-linking and self-competence as dimensions of global self-esteem: Initial validation of a measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65(2), 322–342.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1985). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Tanne, D., Goldbourt, U., & Medalie, J. H. (2004). Perceived family difficulties and prediction of 23-year stroke mortality among middle-aged men. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 18(4), 277–282. doi:10.1159/000080352.

Verkuyten, M., & Masson, K. (1995). ‘New racism’, self-esteem, and ethnic relations among minority and majority youth in the Netherlands. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 23(2), 137–154.

Yeh, C. J. (2002). Taiwanese students’ gender, age, interdependent and independent self-construal, and collective self-esteem as predictors of professional psychological help-seeking attitudes. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 8(1), 19–29.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, A.W. Mosque-Based Social Support and Collective and Personal Self-Esteem Among Young Muslim American Adults. Race Soc Probl 9, 95–101 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-017-9196-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-017-9196-y