Abstract

This study examines the impact of informal social support from family and friends on the well-being of older African Americans. Analyses are based on a nationally representative sample of older African Americans from the National Survey of American Life (n = 837). Three measures of well-being are examined: life satisfaction, happiness and self-esteem. The social support variables include frequency of contact with family and friends, subjective closeness with family and friends, and negative interactions with family. Results indicate that family contact is positively correlated with life satisfaction. Subjective closeness with family is associated with life satisfaction and happiness and both subjective closeness with friends and negative interaction with family are associated with happiness and self-esteem. There are also significant interactions between family closeness and family contact for life satisfaction, as well as friendship closeness and negative interaction with family for happiness. Overall, our study finds that family and friend relationships make unique contributions to the well-being of older African Americans. Qualitative aspects of family and friend support networks (i.e., subjective closeness, negative interactions) are more important than are structural aspects (i.e., frequency of contact). Our analysis verify that relationships with family members can both enhance and be detrimental to well-being. The findings are discussed in relation to prior research on social support and negative interaction and their unique associations with well-being among older African Americans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Social Support and Well-Being Among Aging African Americans

Gerontological research confirms that subjective well-being (SWB) (i.e., life satisfaction, happiness) is an important indicator of the psychological status of older adults. SWB evaluations represent overall assessments of quality of life that encompass both positive and negative features (Diener et al. 1984; Diener 2000). Although there is a large body of research in this area, few studies focus on elderly racial and ethnic minorities and research on older African Americans is especially limited. Further, several questions regarding assessments of SWB and their social correlates are unresolved. First, because SWB is multidimensional (Jivraj et al. 2014), different aspects of SWB are thought to be conceptually distinct in terms of whether they reflect cognitive or evaluative (i.e., life satisfaction), affective (i.e., happiness), or eudemonic or self-assessment (i.e., self-esteem) dimensions. In addition, these components may have different social correlates (Jivraj et al. 2014). We currently have little information as to whether family and friendship support and relationships have distinctive impacts on various well-being constructs (i.e., life satisfaction, happiness, self-esteem). Second, well-being studies examining the impact of family networks and social support typically assess only positive features of these relationships. Less is known about how social connections with peers and friends and problematic social relationships (e.g., conflict, criticism) are associated with diverse measures of SWB. Third, because most well-being studies of older adults focus on samples from the general population (largely non-Hispanic white), we lack reliable information for race and ethinic minority older adults concerning: (1) the overall distribution of well-being evaluations and their relevant social correlates, (2) potential differences in the correlates for different well-being assessments, (3) the impact of social relationships involving peers and friends on SWB, and (4) the role of negative social relationships for SWB.

The current study aims to address these gaps by examining the relation of family and friend support and interaction to diverse SWB indicators among older African Americans. Given the limited work specifically on SWB, this review incorporates related research on the relationship between family and friend social support and relationships and mental health status. The literature review begins with an overview of the convoy model of social relations as a theoretical frame for the current analysis. This is followed by a discussion of theory and research on social relationships and their links to well-being and mental health, focusing on the general adult population. The next section reviews research linking social support and social relationships with well-being among African American adults overall, followed by research on African American elderly. The literature review concludes with a section describing the focus of the current study.

1.1 Convoy Model of Social Relations

The convoy model of social relations (Antonucci and Akiyama 1995; Antonucci et al. 2009; Kahn and Antonucci 1980) posits that social relations are universally necessary, while acknowledging that the level and types of social relations required varies from one individual to another. These important and meaningful relationships, in total, are referred to as one’s convoy of social relations (i.e., social support network). Convoy members consist of family, friends, co-workers, neighbors, and other persons who are significant sources of social support. Convoys are important because they provide individuals with support, including emotional support, assistance, advice, friendship, and caregiving (Antonucci and Akiyama 1995; Kahn and Antonucci 1980). Given that extensive research has documented the beneficial link between social support and SWB, support convoys are ideally positioned to have a significant influence on individuals’ well-being.

The convoy model of social relations assumes that qualitative assessments of one’s social relations (e.g., satisfaction with relationships, adequacy of social support provided by one’s convoy), along with structural characteristics, such as network size, are critical indicators of the social support network and its functioning. That is, when examining social support networks, it is important to assess both the structural characteristics of the network (e.g., size), as well as the individual’s perceptions of the quality of their relationships and the social support provided by convoy members (Kahn and Antonucci 1980; Antonucci and Akiyama 1995). In fact, Kahn and Antonucci (1980) suggest that qualitative evaluations of social support networks are stronger predictors of SWB than structural characteristics of social support networks.

Kahn and Antonucci (1980) conceptualized convoys as consisting of three sets of concentric circles surrounding the individual. These concentric circles represent varying degrees of subjective closeness of network members to the individual. The inner circle consists of network members who are subjectively closest to the individual and provide the most support to the individual. Relationships in this circle are the most intimate—typically parents, spouses, and children populate the inner circle. The outer circle is comprised of persons who, comparatively speaking, are less subjectively close to the individual, but nonetheless are important in the context of social support. Neighbors and co-workers are likely to be in the outer circle. Finally, the middle circle consists of network members who are intermediate in terms of being subjectively close (e.g., close friends, aunt, uncle) to the individual; that is, not as close as those in the inner circle but subjectively closer than those in the outer circle.

The convoy model of social relations incorporates a life course perspective and recognizes the fluidity of social support networks and changes in the composition of convoys throughout the life course. For example, among middle-aged adults, persons 40 to 59 years of age most frequently list spouses, children, and their mothers as members of the inner circle (Antonucci et al. 2004; Antonucci and Akiyama 1987). Persons in their 60 s and older, in contrast, are less likely to list their parents within their inner circle, whom they have likely outlived. These findings highlight how fluid an individual’s convoy is throughout the life course, with members of the convoy moving in and out of the three circles as new members are introduced into the convoy and other members depart. Moreover, Antonucci and Akiyama (1987) found that older adults’ convoys are largely comprised of family members, with family members predominating the inner circle while friends and distant family members are located in the outer circle. The predominance of close family members within the inner circle, who provide the most support, demonstrates the importance of family in the context of social support exchanges.

1.2 Social Relationships, Well-Being and Mental Health

Research on social relationships and health indicates that positive social ties (e.g., social integration, support) have beneficial influences on SWB. Several studies indicate that social support and positive social relationships have beneficial impacts on mental and physical health and SWB among older adults. For example, diverse features of social relationships and social support (i.e., larger social networks, network integration, contact with friends, positive family relationships) are associated with greater life satisfaction (Markides and Martin 1979; Pinquart and Sörensen 2000), self-esteem (Pinquart and Sörensen 2000; Markides and Martin 1979) happiness (Pinquart and Sörensen 2000) and general well-being (Ryan and Willits 2007; Thomas 2009).

Social support and positive social relationships are also protective against depression; persons receiving high levels of social support from friends and family are less likely to be diagnosed with depression and report fewer depressive symptoms (Elder Jr et al. 1995; Gant et al. 1993; Gant and Ostrow 1995; Horwitz et al. 1998; Russell and Cutrona 1991; Siegel et al. 1994). Additionally, both larger social support networks (Siegel et al. 1994) and greater integration within the support network (Gant and Ostrow 1995) are associated with lower levels of depression. In regards to affect, social support is also associated with lower levels of negative affect (e.g., anxiety, anger, loneliness) and higher levels of positive affect (e.g., joy) (Gant and Ostrow 1995; Gant et al. 1993; Ingersoll-Dayton et al. 1997). Further, higher levels of social support from family and friends are associated with fewer reports of daily hassles and lower levels of psychological distress (Elder Jr et al. 1995; Lincoln 2008; Russell and Cutrona 1991).

A growing body of research also examines the impact of problematic social relations, so-called negative interactions (i.e., criticism, conflicts, demands), on SWB. Despite the fact that negative interactions are a recognized feature of social relationships, their influences on SWB have only recently been examined in their own right (Lincoln 2000, 2008). In fact, current research indicates that the deleterious effects of negative interactions on SWB and other mental health outcomes are more potent than the positive impacts of social support (Gray and Keith 2003; Lincoln et al. 2003, 2005). This is the case for several reasons.

Social interactions, particularly those involving close associates, are expected to be positive in nature (Rook 1990). Negative social interactions, however, are unexpected occurrences that violate this normative assumption and are associated with several undesirable reactions and outcomes. First, one of the prominent features of negative interactions is that the target individual experiences the exchange itself as being a stresssful event. Customary responses to experiencing stressful events such as alarm, heightened vigilence and emotional reactivity (Glanz and Schwartz 2008), are frequent sequelae of negative interactions. Negative social interactions also evoke longer term negative affect and depressed mood for those who are the target of these messages (Newsom et al. 2003), as well as impairments in psychological functioning and coping responses to stressors (Rook 1984; Krause 2005). Further, because negative interactions (e.g., criticism, excessive demands) involve evaluative information about the individual, they call into question and threaten positive self-appraisals and erode perceptions of the self as being competent, efficacious and having self-worth and self-esteem (Lincoln 2000).

Secondly, negative interactions impede effective coping because many of the adaptive strategies typically used when confronted with stressful events are themselves dependent upon notions of personal competency and self-efficacy (Glanz and Schwartz 2008). Moreover, individuals typically solicit coping assistance and supports (e.g., material resources, advice and encouragement, role modeling) from social network members when confronted with problems. However, negative interactions that involve members of one’s social networks can complicate the help-seeking process. In effect, negative interactions interfere with and restrict the use of emotional and tangible support resources from others, which is a well-recognized psychosocial mechnism linking social engagement with health and well-being outcomes (Berkman and Glass 2000; Glanz and Schwartz 2008; Heaney and Israel 2008; Lazarus and Folkman 1984).

In sum, because negative interactions are perceived and reacted to as stressors, adversely impact positive self-conceptions, and interfere with the individual’s ability to use cognitive and social resources to effectively manage stressors, they represent a combination of mechanisms and processes that have potential adverse impacts on mental and physical health. In fact, accumulating evidence indicates that negative interactions are associated with adverse mental and physical states (King et al. 2002; Newsom et al. 2003; Seeman and Chen 2002; Tanne et al. 2004), produce high levels of distress for individuals (Zautra et al. 1994) and persist over time (Bolger et al. 1989). Thus, it is expected that this cascade of adverse effects from negative interactions will be associated with decreased SWB among older African American adults.

1.3 Social Support, Well-Being and Mental Health: African Americans

Research specifically on African Americans confirms a positive association between social support and mental health and SWB for this group. For example, frequent support from extended family and being subjectively close to family members are associated with greater life satisfaction (Taylor et al. 2001). Further, subjective family closeness, having fictive kin, number of friends to discuss problems with, and contact with neighbors are positively associated with levels of happiness (Taylor et al. 2001). Studies specifically focusing on mental health outcomes indicate that social support is negatively associated with depressive symptoms (Lincoln et al. 2005). Similarly, Lincoln and Chae (2012) found that frequent emotional support from family is related to a decreased likelihood of a depression diagnosis, and reported satisfaction with received social support is associated with less severe depressive symptoms (Haines et al. 2008; Zea et al. 1996).

Okun and Keith’s (1998) work on the quality of social interactions found that positive social interactions with family and friends were associated with fewer depressive symptoms. Social support is inversely associated with reported psychological distress (Lincoln et al. 2003), suicidal ideation (Lincoln et al. 2012b; Vanderwerker et al. 2007; Wingate et al. 2005), and suicide attempts (Compton et al. 2005; Kaslow et al. 2005; Lincoln et al. 2012b; Vanderwerker et al. 2007). Finally, emerging research on negative aspects of social relationships reveals that, among African Americans, individuals experiencing higher levels of negative interaction are more likely to report depressive symptoms and have a higher likelihood of being diagnosed with depression (Lincoln and Chae 2012; Lincoln et al. 2005). Further, negative interaction with family members is associated with increased psychological distress (Lincoln et al. 2005; Lincoln 2007) and suicidality (Lincoln et al. 2012b).

1.4 Social Support, Well-Being and Mental Health: African American Elderly

The few available studies on social support and SWB relationships among older African Americans are consistent with findings for the adult population. Social relationships and support (e.g., emotional support, social participation and affiliation) are positively associated with well-being (Walls 1992) and life satisfaction (Jackson et al. 1977; Johnson et al. 1982), while inversely associated with psychological distress (Dilworth-Anderson et al. 1999; Lincoln et al. 2003). Further, research on suicidal behaviors indicates that the lack of social support and instrumental aid from a confidant is associated with greater risk of suicidal ideation (Cook et al. 2002); having fewer close confidants and limited contact with friends is associated with completed suicide (Turvey et al. 2002). However, in contrast to these findings, Lincoln et al. (2010a) found that emotional support from family members was unrelated to having a mood or anxiety disorder and the number of diagnosed psychological disorders.

Although overall older adults are less likely to report negative interaction, it, nonetheless, has deleterious effects on their SWB and mental health. High levels of negative interaction with family and friends is associated with a lower sense of mastery (Lincoln 2007) and greater psychological distress (Okun and Keith 1998) compared to those experiencing low levels of negative interaction. Negative interaction is positively associated with number of DSM-IV conditions among older African Americans including higher odds of having a lifetime mood disorder, a lifetime anxiety disorder and the overall number of lifetime mood and anxiety disorders (Lincoln et al. 2010b).

Finally, it is important to take into account whether demographic factors are associated with SWB among older African Americans. Prior work indicates that older age itself is associated with higher levels of life satisfaction, happiness, and SWB among African Americans, both within the entire adult age range, as well as persons 55 years and older (Lincoln et al. 2010b; Foster 1992; Tran et al. 1991; Chatters 1988). Older African Americans who are married report higher levels of life satisfaction and happiness compared to those who are separated, divorced, or widowed (Lincoln et al. 2010b; Chatters 1988). Finally, income is positively associated with self-esteem and life satisfaction, though its association with life satisfaction is equivocal (Foster 1992; Tran et al. 1991).

In summary, this broad body of work suggests that social support and relationships are associated with positive SWB outcomes, while negative interaction has harmful associations with a range of SWB and mental health indicators. Unfortunately, because relatively few studies focus specifically on older African Americans, these findings await further confirmation within appropriate samples.

1.5 Focus of the Study

The present study examines the social (i.e. perceived closeness, contact and negative interaction) correlates of three measures of SWB among older African Americans. The study incoporates several social support and relationship measures (e.g., subjective closeness, frequency of contact, negative interaction) that are assessed for both family and friend networks. Based on prior research, we expect that findings will converge with existing evidence regarding their associations with SWB measures (i.e., positive associations for support and contact; negative associations for negative interaction). With respect to possible differential impacts of family versus friend factors on SWB assessments, the convoy model suggests that family are prominent members of an individual’s support convoy and thus, family factors may be more important than friend factors for SWB assessments.

Although tentative, we also anticipate potential differences in the social relationship correlates of specific SWB assessments (i.e., life satisfaction, happiness, self-esteem) for several reasons. First, different SWB measures tap distinctive domains of experience. Life satisfaction reflects cognitive or evaluative assessments of life quality, whereas happiness taps affective content and self-esteem is thought to reflect eudemonic (i.e., self-assessment) content (Chatters 1988; Diener 2000; Diener et al. 1984; Jivraj et al. 2014). Further, measures of social network relationships differ with respect to the objective versus subjective nature of their content. Objective measures of social network relationships provide information on the specific characteristics (e.g., frequency of contact) of networks. In contrast, measures of the qualitative features of social network relationships (e.g., closeness, supportiveness) represent subjective evaluations of these relationships, which tend to demonstrate stronger associations with psychosocial outcomes (e.g., self-perceptions and affective outcomes) than do objective measures. In a similar vein, research on social support convoys indicate that qualitative features of convoy relationships demonstrate stronger associations with SWB than do structural characteristics (Antonucci and Akiyama 1995; Kahn and Antonucci 1980).

Given these associations, we anticipate that factors reflecting qualitative aspects of social relations (e.g., closeness, negative interaction) will have stronger associations with SWB evaluations than objective measures (e.g., level of contact). We further anticipate that qualitative aspects of social relations will have stronger associations with happiness and self-esteem ratings (given their affective and eudemonic content, respectively) as compared to life satisfaction assessments (as an evaluative component of SWB). Finally, prior research indicates that although social support and negative interaction co-occur within social networks, they are conceptually discrete and impact SWB and mental health in distinctive ways (Lincoln et al. 2003; Lincoln et al. 2010a). Accordingly, we anticipate that social support will be associated with higher levels of life satisfaction, happiness, and self-esteem, while the opposite will be true for negative interaction.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample

The National Survey of American Life: Coping with Stress in the 21st Century (NSAL) was collected by the Program for Research on Black Americans at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research. The African American sample is the core sample of the NSAL. The core sample consists of 64 primary sampling units (PSUs). Fifty-six of these primary areas overlap substantially with existing Survey Research Center National Sample primary areas. The remaining eight primary areas were chosen from the South in order for the sample to represent African Americans in the proportion in which they are distributed nationally. The African American sample is a nationally representative sample of households located in the 48 coterminous states with at least one Black adult 18 years or over who did not identify ancestral ties in the Caribbean.

The data collection was conducted from February 2001 to June 2003. A total of 6082 interviews were conducted with persons aged 18 or older, including 3570 African Americans, 891 non-Hispanic whites, and 1621 Blacks of Caribbean descent. Fourteen percent of the interviews were completed over the phone and 86 % were administered face-to-face in respondents’ homes. Respondents were compensated for their time. The sample for this analysis consists of 837 African Americans who are aged 55 or older.

The overall response rate was 72.3 %. This is excellent given the difficulty and expense to conduct survey fieldwork and data collection among African Americans (especially lower income African Americans) who are more likely to reside in major urban areas. Final response rates for the NSAL two-phase sample designs were computed using the American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) guidelines (for Response Rate 3 samples) (American Association for Public Opinion Research 2006) (see Jackson et al. 2004) for a more detailed discussion of the NSAL sample). The NSAL data collection was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Subjective Well-Being

Three SWB variables are examined in this analysis (descriptive information for SWB and social support network correlates are included in Table 1). Life satisfaction is measured by the question: In general, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days? Would you say very satisfied (4), somewhat satisfied (3), somewhat dissatisfied (2), or very dissatisfied (1)? Overall happiness is assessed by the following question: Taking all things together, how would you say things are these days? Would you say you are very happy (4), pretty happy (3), or not too happy these days (2)? A few respondents volunteered that they were “not happy at all” (1). Self-esteem is measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg 1965). The scale is comprised of 10 statements reflecting respondents’ self-perceptions, and responses were given based on a 4-point Likert type scale with 1 indicating strongly disagree and 4 indicating strongly agree. Higher values on this scale indicate higher self-esteem levels.

2.2.2 Social Support Network Correlates

Several indicators of social support (i.e., frequency of contact with family, frequency of contact with friends, subjective closeness to family, subjective closeness to friends, negative interaction with family) are included as measures of social support network. Subjective closeness to family is assessed by the question: How close do you feel towards your family members? Would you say very close (4), fairly close (3), not too close (2), or not close at all (1). Frequency of contact with family is measured by the question: How often do you see, write or talk on the telephone with family or relatives who do not live with you? Would you say nearly everyday (7), at least once a week (6), a few times a month (5), at least once a month (4), a few times a year (3), hardly ever (2), or never (1). Subjective closeness to friends and frequency of contact with friends are measured by questions similar to the family network variables. Negative interaction with family members was evaluated with a three-item index. Respondents were asked, “Other than your (spouse/partner) how often do your family members: (a) make too many demands on you, (b) criticize you and the things you do, and (c) try to take advantage of you?” The response categories for these questions are very often, fairly often, not too often, and never. Although negative interactions, subjective closeness, and frequency of contact all assess varied characteristics of social relations, negative interactions specifically underscore the adverse elements of social relations. Accordingly, higher values on this index indicate more frequent negative interactions with family members.

Several demographic factors (i.e., gender, age, marital status, region, education, family income) are included as covariates. Missing data for family income and education were imputed using an iterative regression-based multiple imputation approach incorporating information about age, sex, region, race, employment status, marital status, home ownership, and nativity of household residents. Income is coded in dollars, and for the multivariate analysis only. Natural log transformation was used in order to address the skewedness of income (Tabachnick and Fidell 2006). The natural log of income was also used in order to increase effect sizes and provide a better understanding of the net impact of income on the SWB variables.

2.3 Analysis Strategy

All analyses are conducted using Stata 11.2, which uses the Taylor expansion approximation technique for calculating the complex design-based estimates of variance. All of the analyses utilize analytic weights. Statistical analyses account for the complex multistage clustered design of the NSAL sample, unequal probabilities of selection, nonresponse, and poststratification to calculate weighted, nationally representative population estimates and standard errors. Based on prior research, regression models are estimated for all SWB variables in relation to their social support correlates. Similarly, prior research (Lincoln et al. 2012a; Taylor et al. 2013) suggests that family factors (negative family interaction, family and friend closeness and contact) may interact with one another in their effects on SWB. Interaction terms are constructed (i.e., family contact × family closeness, friend closeness × negative interaction) and tested in regression models for the SWB variables. All analyses control for demographic differences.

3 Results

The demographic characteristics of the sample and the distribution of the study varaibles are presented in Table 1. Approximately 60 % of the sample is female, and the mean age of respondents is 66.7 years. Mean family income is $27,652 and, on average, respondents report some high school education (11 years). More than half of respondents reside in the South and close to one-third of the sample is widowed. In general, respondents report high levels of life satisfaction, happiness, and self-esteem. With respect to social support and network characteristics, respondents indicate relatively frequent contact with family, feeling subjectively close to family and relatively minimal levels of negative interaction with family. Respondents also report relatively high levels of subjective closeness to and interaction with friends.

Results of the regression analysis for life satisfaction are presented in Table 2. Subjective closeness to family is positively associated with life satisfaction. In contrast, negative interaction with family, family contact, and friend contact and friend closeness are all unrelated to life satisfaction (Model 1). In Model 2, frequency of contact with family is positively associated with life satisfaction; the significant interaction between family closeness and family contact on life satisfaction (presented in Fig. 1) indicates that contact with family has a greater effect among older adults who are not subjectively close to their family than those who are close to their family. For those who are subjectively closer to their family, increased contact only marginally increases life satisfaction ratings. However, for those who exhibit low levels of closeness to family, increases in family contact are associated with a substantial increase in life satisfaction.

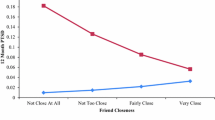

Turning to happiness ratings, subjective closeness to friends, closeness to family, and negative interaction are associated with happiness (Table 2, Model 1). Specifically, older adults reporting higher levels of subjective closeness to friends and subjective closeness to family are also more likely to report higher levels of happiness, while those reporting high levels of negative interaction with family have lower happiness ratings. Contact with family and contact with friends, however, are unrelated to happiness evaluations. The significant interaction (Model 2) between subjective closeness to friends and negative interaction with family (Fig. 2) indicates that respondents who are close to their friends and experience minimal negative interaction with their family report the highest level of happiness. Further, it appears that negative interaction levels with family have less influence on happiness for persons who are subjectively close to their friends. Older adults who are not close to their friends and also experience high levels of negative interaction with family have very low levels of happiness.

As shown in Table 2, subjective closeness to friends and negative interaction with family are associated with self-esteem. Older African Americans reporting higher levels of closeness to friends exhibit higher self-esteem than those who are less close to their friends. Additionally, individuals who experience greater negative interaction with family report lower self-esteem than those who experience minimal negative interaction. Family contact, friend contact and closeness to family are unrelated to self-esteem.

4 Discussion

This investigation of the impact of social support and social relationships on older African Americans’ SWB makes several unique contributions to a small but emerging body of research (Lincoln et al. 2010b; Nguyen et al. 2013; Peterson et al. 2013). This analysis, based on a national probability sample of older African Americans, investigated both family and friendship relationships and their positive and negative associations with several indicators of SWB. Overall, our study finds that both family members and friends make unique contributions to the well-being of older African Americans and relationships with family members both enhance and diminish well-being. However, these effects were not universal across all of the SWB measures examined.

Subjective closeness to family was related to higher levels of life satisfaction and happiness, but not self-esteem, while closeness to friends was associated with higher levels of happiness and self-esteem, but not life satisfaction. Frequency of contact with family was predictive of higher levels of life satisfaction (the only significant finding for contact). These findings indicate that social relationships involving family and friends (particularly perceived closeness vs. contact) are important for assessments of SWB among older African Americans.

As anticipated, we found that measures of subjective closeness to family and friends were more important than contact with family and friends for SWB, particularly as positive correlates of happiness and self-esteem. However, an anticipated positive relationship between family closeness and self-esteem was not verified. Further, while we expected family closeness to be less important for life satisfaction (as an evaluative aspect of SWB), it was associated with life satisfaction in the form of a statistical interaction with family contact. Overall, these findings are consistent with other work indicating that family and friend relationships are important for older African Americans in terms of emotional support and companionship, as well as other forms (e.g., goods and services, transportation) of assistance (Taylor et al. 2014). Family members tend to be reliable and stable sources of social support for older adults (Laditka and Laditka 2001; Swartz 2009) and become especially important for older African Americans who come to rely more heavily on kin due to declines in their peer social networks as they age (Conway et al. 2013; Fung et al. 2001; Taylor et al. 2014)..

However, prior research also indicates that friendships are important for the well-being of older adults. Social support from friends is associated with elevated levels of self-esteem (Poulin et al. 2012) and well-being (Larson et al. 1986) and lower levels of depression and loneliness (Poulin et al. 2012; Zhang and Li 2011). Friendship network size is positively associated with happiness (Ellison 1990), and more frequent contact with friends is correlated with greater levels of SWB (Helliwell and Putnam 2004; Pinquart and Sörensen 2000). In fact, in certain contexts, friendships can exert greater influence on individuals’ SWB than family relationships (Pinquart and Sörensen 2000; Helliwell and Putnam 2004; Larson et al. 1986); friendships are often of higher quality than family relationships because older adults can more easily disengage from unsatisfactory friendships than is the case for negative family relationships (Pinquart and Sörensen 2000). The positive influence of subjective closeness with friends found in this study underscores the importance of qualitative features of friendship for self-evaluative or eudemonic (i.e., self-esteem) and affective (i.e., happiness) components of SWB evaluations; this was not the case for life satisfaction assessments.

Negative interaction with family was associated with lower levels of happiness and self-esteem, but was unrelated to life satisfaction. These findings are consistent with research suggesting that negative interactions are associated with negative affect (Newsom et al. 2003), undermine positive self-perceptions (Lincoln 2007; Todd and Worell 2000) and hinder effective coping behaviors and psychological functioning (Krause 2005; Lincoln 2000; Newsom et al. 2003; Rook 1984). Prior studies on African Americans also found that negative interaction is associated with a lower sense of mastery (Lincoln 2007), greater psychological distress (Okun and Keith 1998), and greater odds of being diagnosed with a range of mood and anxiety disorders (Lincoln et al. 2010a).

The frequency-salience theory indicates that although negative interactions are less likely to occur than positive social exchanges, their impact on SWB is clearly substantial. In fact, negative interactions are often perceived as stressors due to their unexpected nature (Rook 1990), the fact that they deviate from general expectations of civility, and because they are experienced as upsetting and stressful events. For these reasons, negative interactions adversely influence SWB, particulary affective dimensions of SWB. In the present analysis, the absence of a relationship between negative interaction with family and life satisfaction supports the notion that life satisfaction evaluations constitute cognitive or evaluative assessments of life quality. In contrast, happiness and self-esteem draw more heavily on affective content and personal perceptions of self, respectively, which are more vulnerable to the impact of negative interactions with family. Interestingly, contact with friends was not a significant correlate for any of the SWB measures indicating that it is not a reliable correlate for older African Americans. Instead, subjective appraisals of relationships (e.g., subjective closeness to family, subjective closeness to friends) had stronger associations than structural features of social support networks (e.g., frequency of contact). This is consistent with expectations from the convoy model of social relations, in which relationship quality exerts greater effects on SWB than the structural characteristics of social support networks (Antonucci and Akiyama 1995; Kahn and Antonucci 1980).

The interpretation of the significant interaction between subjective closeness to family and contact with family for life satisfaction further supports the notion that subjective appraisals are more pivotal as correlates of subjective SWB than are structural features of networks for particular groups of older persons. Irrespective of their reported level of contact with family, older adults reporting high levels of subjective closeness to family, also had high levels of life satisfaction. Apparently, older adults’ positive appraisals of their familial relationships compensated for the infrequent contact they had with their family. Thus, despite infrequent family contact, persons with higher levels of subjective family closeness experienced high levels of life satisfaction. In contrast, persons reporting low family closeness and low family contact had the lowest levels of life satisfaction; however, increases in contact with family was associated with higher levels of life satisfaction. The fact that family closeness was strongly associated with SWB confirms notions from the convoy model about the importance of qualititative aspects of relations and emphasizes the critical influence of family relationships for SWB. Furthermore, the fact that frequency of contact with family members had no effect on life satisfaction for respondents who indicated high subjective closeness to family members supports the socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen 1993; Carstensen et al. 2003). The socioemotional selectivity theory suggests that older adults are at a developmental stage in which they perceive their remaining time in life to be limited. Because of this perspective, older adults tend to reorient their goals to focus more on emotionally meaningful aspects of life, including relationships, and maximizing positive emotional experiences. As a result, subjective closeness to family members, which taps into emotional meaning, may be especially important for life satisfaction in older adults. It may, in fact, override the negative impact of infrequent family contact on life satisfaction. That is, even when older adults have infrequent contact with their family, if they are subjectively close to their family they still exhibit high levels of life satisfaction because they derive emotional meaning from this closeness.

The interaction between subjective closeness to friends and negative interaction with family on happiness ratings indicated that closeness to friends offsets the impact of negative family interaction on happiness. In contrast, older adults who were not close to their friends and experienced high levels of negative interaction with family reported the lowest level of happiness. In essence, the detrimental impact of negative interaction with family on happiness was diminished for older adults who where subjectively closer to their friends as compared to those who did not feel close to their friends. This finding confirms the deleterious effects of negative interaction on SWB evaluations, as well as the beneficial impact of positive friend relationships in offsetting negative family interactions. Although the average negative interaction score for the sample is relatively low, the significant main effects of negative interaction on happiness and self-esteem, coupled with the interaction effect between negative interaction and subjective closeness to friends, demonstrates the potency of negative interactions on SWB.

These findings are consistent with research indicating both direct and indirect relationships effects of social support on SWB (Rook 1984). The direct positive effects of family closeness for happiness and friend closeness for self-esteem, are consistent with a large body of research on social support linkages to decreased feelings of loneliness and sadness and increased feelings of trust (Helliwell and Putnam 2004). Further, within stress and coping frameworks social support is important in buffering the impact of stress, such that when a person is faced with a stressful situation, they evaluate and mobilize the psychological and social resources available for coping with the stressor and respond accordingly (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Our findings similarly indicated that social support from friends is a critical social resource that mitigates the negative effects of negative family interaction on happiness.

This confirms findings from previous studies indicating that support from friends buffers the negative effects of partner strain on psychological well-being (Walen and Lachman 2000). In the presence of marital conflict, supportive friendships also buffers against lowered levels of marital sastisfaction (Walen and Lachman 2000). Additionally, support from friends has been shown to mitigate the harmful effects of friendship conflict on physical health (Proulx et al. 2009). Friends serve many roles for older adults, ranging from companions and confidants to caregivers. In fact, support reciprocity, which is associated with relationship satisfaction, tends to be higher in friendships than in relationships with adult children (Adams and Blieszner 1995). Further, friends provide a range of support including companionship, instrumental support (e.g., home repairs, transportation, errands and chores during illness), and emotional support (e.g., love and affection, listening, affirmation of self-worth) (Adams and Blieszner 1995; Armstrong and Goldsteen 1991; Blieszner 2006; Blieszner and Roberto 2012; Shea et al. 1988). For certain types of support, such as companionship and coping with bereavement issues, friends are more preferred than family (Adams and Blieszner 1995). Friendships can influence psychological well-being in several ways. First, friendships are perceived as achieved relationships, whereas familial relationships are perceived as ascribed relationships (Adams and Blieszner 1995). Consequently, friendships can provide a sense of accomplishment and competence in interpersonal relationship domains. Second, prior research has demonstrated a strong association between friendship quality and psychological well-being (Adams and Blieszner 1995). For example, Antonucci, Lansford, and Akiyama (2001) found that older women who had close, intimate friends in whom they could confide reported lower levels of depressive symptoms than women who did not did not have confidants.

Although previous research among African Americans has largely focused on relationships with family, the current analysis revealed the importance of examining both family and friendship correlates of SWB among older African Americans. The use of several relationship measures involving both family and friends, provided a more complete representation and understanding of the functioning of older African Americans’ family and friend networks. In addition, multiple measures of SWB permitted a more in-depth examination of their distinctiveness in how family and friend support and social interaction factors are associated with dimensions of SWB. Overall, the findings demonstrated the importance of family and friend relationships in bolstering SWB and the detrimental impacts of negative family interaction on selected aspects of SWB. Further, the findings identified situations embodying specific risks for lower SWB for older African Americans; that is, limited family contact coupled with low family closeness for life satisfaction and low friendship closeness in the presence of high negative family interaction for happiness.

Despite the strengths of the present study, interpretations of these findings should be examined within the context of the study’s limitations. All measures in this study were self-reported, which is susceptible to recall and social desirability biases. Because segments of the population such as homeless and institutionalized individuals were not represented, our findings are not generalizable to these subgroups. Additionally, although findings supported the deleterious influence of negative interactions with family members on SWB, we were unable to investigate the impact of negative interaction with friends on SWB, as the NSAL did not have this information. Future research should examine the relation between negative interactions with friends, in addition to negative interaction with family members, and SWB to determine if negative interactions impact SWB differentially depending on the source of the interaction (i.e., family members vs. friends). Lastly, causal inferences concerning the connections between support and social interaction and SWB are problematic with cross-sectional data and longitudinal data are preferred.

Nevertheless, this study provides a more comprehensive picture of the associations between family and friend support and interaction and SWB that verified that family and friendship networks can be both beneficial as well as detrimental to SWB. Our analysis further found that qualitative features of support networks (subjective closeness to family and friends, negative family interaction) were generally more important for SWB than structural features of networks (frequency of contact). Study findings contribute to a growing literature on SWB and the role of both positive and negative relationships on SWB within diverse segments of the older population. More broadly, this study reinforces the importance of focused research on race/ethnic minority groups within the United States in advancing a more nuanced understanding of the social correlates of SWB within these groups.

References

Adams, R. G., & Blieszner, R. (1995). Aging well with friends and family. American Behavioural Scientist, 39, 209–224.

American Association for Public Opinion Research. (2006). Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys (4th ed.). Lenexa, KS: American Association for Public Opinion Research.

Antonucci, T. C., & Akiyama, H. (1987). Social networks in adult life and a preliminary examination of the convoy model. Journal of Gerontology, 42(5), 519–527.

Antonucci, T. C., & Akiyama, H. (1995). Convoys of social relations: Family and friendships within a life span context. In R. Blieszner & V. H. Bedford (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the family (pp. 355–371). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Antonucci, T. C., Akiyama, H., & Takahashi, K. (2004). Attachment and close relationships across the life span. Attachment & Human Development, 6(4), 353–370.

Antonucci, T. C., Birditt, K. S., & Akiyama, H. (2009). Convoys of social relations: An interdisciplinary approach. In V. L. Bengtson, D. Gans, N. M. Putney, & M. Silverstein (Eds.), Handbook of theories of aging (pp. 247–260). New York: Springer.

Antonucci, T. C., Lansford, J. E., & Akiyama, H. (2001). Impact of positive and negative aspects of marital relationships and friendships on well-being of older adults. Applied Developmental Science, 5(2), 68–75.

Armstrong, M. J., & Goldsteen, K. S. (1991). Friendship support patterns of older American women. Journal of Aging Studies, 4(4), 391–404.

Berkman, L. F., & Glass, T. (2000). Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. Social epidemiology, 1, 137–173.

Blieszner, R. (2006). A lifetime of caring: Dimensions and dynamics in late-life close relationships. Personal Relationships, 13(1), 1–18.

Blieszner, R., & Roberto, K. A. (2012). Partners and friends in adulthood. In S. K. Whitbourne & M. Sliwinski (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of adulthood and aging (pp. 381–398). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Bolger, N., DeLongis, A., Kessler, R. C., & Schilling, E. A. (1989). Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 808–818.

Carstensen, L. L. (1993). Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In J. E. Jacobs (Ed.), Developmental perspectives on Motivation: Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1992 (pp. 209–254). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Carstensen, L. L., Fung, H. H., & Charles, S. T. (2003). Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and emotion, 27(2), 103–123.

Chatters, L. M. (1988). Subjective well-being evaluations among older Black Americans. Psychology and Aging. Psychology and Aging, 3(2), 184–190.

Compton, M. T., Thompson, N. J., & Kaslow, N. J. (2005). Social environment factors associated with suicide attempt among low-income African Americans: The protective role of family relationships and social support. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(3), 175–185.

Conway, F., Magai, C., Jones, S., Fiori, K., & Gillespie, M. (2013). A six-year follow-up study of social network changes among African-American, Caribbean, and U.S.-born Caucasian urban older adults. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 76(1), 1–27.

Cook, J. M., Pearson, J. L., Thompson, R., Black, B. S., & Rabins, P. V. (2002). Suicidality in older African Americans: Findings from the EPOCH study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 10(4), 437–446. doi:10.1097/00019442-200207000-00010.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.34.

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (1984). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Dilworth-Anderson, P., Williams, S. W., & Cooper, T. (1999). The contexts of experiencing emotional distress among family caregivers to elderly African Americans. Family Relations, 48(4), 391–396.

Elder, G. H, Jr, Eccles, J. S., Ardelt, M., & Lord, S. (1995). Inner-city parents under economic pressure: Perspectives on the strategies of parenting. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57(3), 771–784.

Ellison, C. G. (1990). Family ties, friendships, and subjective well-being among Black Americans. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 298–310.

Foster, M. F. (1992). Health promotion and life satisfaction in elderly Black adults. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 14(4), 444–463.

Fung, H. H., Carstensen, L. L., & Lang, F. R. (2001). Age-related patterns in social networks among European Americans and African Americans: Implications for socioemotional selectivity across the life span. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 52(3), 185–206.

Gant, L. M., Nagda, B. A., Brabson, H. V., Jayaratne, S., Chess, W. A., & Singh, A. (1993). Effects of social support and undermining on African American workers’ perceptions of coworker and supervisor relationships and psychological well-being. Social Work, 38(2), 158–164.

Gant, L. M., & Ostrow, D. G. (1995). Perceptions of social support and psychological adaptation to sexually acquired HIV among White and African American men. Social Work, 40(2), 215–224.

Glanz, K., & Schwartz, M. D. (2008). Stress, coping, and health behavior. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (4th ed., pp. 211–236). San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Gray, B. A., & Keith, V. M. (2003). The benefits and costs of social support for African American women. In D. R. Brown & V. M. Keith (Eds.), In and out of our rights minds: The mental health of African American women (pp. 242–257). New York: Columbia University Press.

Haines, V. A., Beggs, J. J., & Hurlbert, J. S. (2008). Contextualizing health outcomes: Do effects of network structure differ for women and men? Sex Roles, 59(3–4), 164–175. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9441-3.

Heaney, C. A., & Israel, B. A. (2008). Social networks and social support. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (Vol. 3, pp. 185–209). San Francisco: Wiley.

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions-Royal Society of London Series B Biological Sciences, 359, 1435–1446.

Horwitz, A. V., McLaughlin, J., & White, H. R. (1998). How the negative and positive aspects of partner relationships affect the mental health of young married people. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 39(2), 124–136.

Ingersoll-Dayton, B., Morgan, D., & Antonucci, To C. (1997). The effects of positive and negative social exchanges on aging adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 52(4), S190–S199.

Jackson, J. S., Bacon, J. D., & Peterson, J. (1977). Life satisfaction among Black urban elderly. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 8(2), 169–179.

Jackson, J. S., Neighbors, H. W., Nesse, R. M., Trierweiler, S. J., & Torres, M. (2004). Methodological innovations in the National Survey of American Life. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(4), 289–298.

Jivraj, S., Nazroo, J., Vanhoutte, B., & Chandola, T. (2014). Aging and subjective well-being in later life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(6), 930–941.

Johnson, F., Cloyd, C., & Wer, J. A. (1982). Life satisfaction of poor urban Black aged. Advances in Nursing Science, 4(3), 27–34.

Kahn, R. L., & Antonucci, T. C. (1980). Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles, and social support. In P. B. Baltes & O. G. Brim (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (Vol. 3, pp. 253–286). New York: Academic Press.

Kaslow, N. J., Sherry, A., Bethea, K., Wyckoff, S., Compton, M. T., Grall, M. B., et al. (2005). Social risk and protective factors for suicide attempts in low income African American men and women. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35(4), 400–412.

King, A. C., Atienza, A., Castro, C., & Collins, R. (2002). Physiological and affective responses to family caregiving in the natural setting in wives versus daughters. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 9(3), 176–194.

Krause, N. (2005). Negative interaction and heart disease in late life: Exploring variations by socioeconomic status. Journal of Aging and Health, 17(1), 28–55.

Laditka, J. N., & Laditka, S. B. (2001). Adult children helping older parents: Variations in likelihood and hours by gender, race, and family role. Research on Aging, 23(4), 429–456. doi:10.1177/0164027501234003.

Larson, R., Mannell, R., & Zuzanek, J. (1986). Daily well-being of older adults with friends and family. Psychology and Aging, 1(2), 117–126.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Lincoln, K. D. (2000). Social support, negative social interactions, and psychological well-being. Social Service Review, 74(2), 231–252.

Lincoln, K. D. (2007). Financial strain, negative interactions, and mastery: Pathways to mental health among older African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology, 33(4), 439–462. doi:10.1177/0095798407307045.

Lincoln, K. D. (2008). Personality, negative interactions, and mental health. The Social Service Review, 82(2), 223–251. doi:10.1086/589462.

Lincoln, K. D., & Chae, D. H. (2012). Emotional support, negative interaction and major depressive disorder among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(3), 361–372. doi:10.1007/s00127-011-0347-y.

Lincoln, K. D., Chatters, L. M., & Taylor, R. J. (2003). Psychological distress among Black and White Americans: Differential effects of social support, negative interaction and personal control. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(3), 390–407.

Lincoln, K. D., Chatters, L. M., & Taylor, R. J. (2005). Social support, traumatic events, and depressive symptoms among African Americans. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(3), 754–766.

Lincoln, K. D., Taylor, R. J., Bullard, K. M., Chatters, L. M., Woodward, A. T., Himle, J. A., et al. (2010a). Emotional support, negative interaction and DSM IV lifetime disorders among older African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL). International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(6), 612–621. doi:10.1002/gps.2383.

Lincoln, K. D., Taylor, R. J., Chae, D. H., & Chatters, L. M. (2010b). Demographic correlates of psychological well-being and distress among older African Americans and Caribbean Black adults. Best Practices in Mental Health, 6(1), 103–126.

Lincoln, K. D., Taylor, R. J., & Chatters, L. M. (2012a). Correlates of emotional support and negative interaction among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Journal of Family Issues, 34(9), 1262–1290. doi:10.1177/0192513x12454655.

Lincoln, K. D., Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., & Joe, S. (2012b). Suicide, negative interaction and emotional support among black Americans. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(12), 1947–1958. doi:10.1007/s00127-012-0512-y.

Markides, K. S., & Martin, H. W. (1979). A causal model of life satisfaction among the elderly. Journal of Gerontology, 34(1), 86–93.

Newsom, J. T., Nishishiba, M., Morgan, D. L., & Rook, K. S. (2003). The relative importance of three domains of positive and negative social exchanges: A longitudinal model with comparable measures. Psychology and Aging, 18(4), 746–754.

Nguyen, A. W., Taylor, R. J., Peterson, T., & Chatters, L. M. (2013). Health, disability, psychological well-being, and depressive symptoms among older African American women. Women, Gender, and Families of Color, 1(2), 105–123.

Okun, M. A., & Keith, V. M. (1998). Effects of positive and negative social exchanges with various sources on depressive symptoms in younger and older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53(1), P4–P20.

Peterson, T. L., Chatters, L. M., Taylor, R. J., & Nguyen, A. W. (2013). Subjective well-being of older African Americans with DSM IV psychiatric disorders. Journal of Happiness Studies,. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9470-7.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2000). Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 15(2), 187–224.

Poulin, J., Deng, R., Ingersoll, T. S., Witt, H., & Swain, M. (2012). Perceived family and friend support and the psychological well-being of American and Chinese elderly persons. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 27(4), 305–317. doi:10.1007/s10823-012-9177-y.

Proulx, C. M., Helms, H. M., Milardo, R. M., & Payne, C. C. (2009). Relational support from friends and wives’ family relationships: The role of husbands’ interference. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26(2–3), 195–210.

Rook, K. S. (1984). The negative side of social interaction: Impact on psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(5), 1097–1108.

Rook, K. S. (1990). Stressful aspects of older adults’ social relationships: Current theory and research. In M. A. P. M. A. P. Stephens, J. H. Crowther, S. E. Hobfall, & D. L. Tennenbaum (Eds.), Stress and coping in later life (pp. 173–192). Washington, DC: Hemisphere.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Russell, D. W., & Cutrona, C. E. (1991). Social support, stress, and depressive symptoms among the elderly: Test of a process model. Psychology and Aging, 6(2), 190–201.

Ryan, A. K., & Willits, F. K. (2007). Family ties, physical health, and psychological well-being. J Aging Health, 19(6), 907–920. doi:10.1177/0898264307308340.

Seeman, T., & Chen, X. (2002). Risk and protective factors for physical functioning in older adults with and without chronic conditions: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(3), S135–S144.

Shea, L., Thompson, L., & Blieszner, R. (1988). Resources in older adults’ old and new friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 5(1), 83–96.

Siegel, K., Raveis, V. H., & Karus, D. (1994). Psychological well-being of gay men with AIDS: Contribution of positive and negative illness-related network interactions to depressive mood. Social Science and Medicine, 39(11), 1555–1563.

Swartz, T. T. (2009). Intergenerational family relations in adulthood: Patterns, variations, and implications in the contemporary United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 35(1), 191–212. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134615.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2006). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education.

Tanne, D., Goldbourt, U., & Medalie, J. H. (2004). Perceived family difficulties and prediction of 23-year stroke mortality among middle-aged men. Cerebrovasc Dis, 18(4), 277–282. doi:10.1159/000080352.

Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., Hardison, C. B., & Riley, A. (2001). Informal social support networks and subjective well-being among African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology, 27(4), 439–463. doi:10.1177/0095798401027004004.

Taylor, R. J., Forsythe-Brown, I., Taylor, H. O., & Chatters, L. M. (2013). Patterns of emotional social support and negative interactions among African American and Black Caribbean extended families. Journal of African American Studies, 18(2), 147–163.

Taylor, R. J., Hernandez, E., Nicklett, E., Taylor, H. O., & Chatters, L. M. (2014). Informal social support networks of African Americans, Latino, Asian Americans and Native Americans older adults. In K. E. Whitfield & T. A. Baker (Eds.), The handbook on minority aging. New York: Springer.

Thomas, P. A. (2009). Is it better to give or to receive? Social support and the well-being of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B(3), 351–357.

Todd, J. L., & Worell, J. (2000). Resilience in low-income, employed, African American women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24(2), 119–128. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb00192.x.

Tran, T. V., Wright, R., & Chatters, L. M. (1991). Health, stress, psychological resources, and subjective well-being among older Blacks. Psychology and Aging, 6(1), 100–108.

Turvey, C. L., Conwell, Y., Jones, M. P., Phillips, C., Simonsick, E., Pearson, J. L., et al. (2002). Risk factors for late-life suicide: A prospective, community-based study. American Journal of Geriatric Psych, 10(4), 398–406.

Vanderwerker, L. C., Chen, J. H., Charpentier, P., Paulk, M. E., Michalski, M., & Prigerson, H. G. (2007). Differences in risk factors for suicidality between African American and White patients vulnerable to suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(1), 1–9.

Walen, H. R., & Lachman, M. E. (2000). Social support and strain from partner, family, and friends: Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17(1), 5–30.

Walls, C. T. (1992). The role of church and family support in the lives of older African Americans. Generations, 16(3), 33–36.

Wingate, L. R., Bobadilla, L., Burns, A. B., Cukrowicz, K. C., Hernandez, A., Ketterman, R. L., et al. (2005). Suicidality in African American men: The roles of southern residence, religiosity, and social support. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35(6), 615–629.

Zautra, A. J., Burleson, M. H., Matt, K. S., Roth, S., & Burrows, L. (1994). Interpersonal stress, depression, and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis patients. Health Psychology, 13(2), 139–148.

Zea, M. C., Belgrave, F. Z., Townsend, T. G., Jarama, S. L., & Banks, S. R. (1996). The influence of social support and active coping on depression among African Americans and Latinos with disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 41(3), 225–242.

Zhang, B., & Li, J. (2011). Gender and marital status differences in depressive symptoms among elderly adults: The roles of family support and friend support. Aging & Mental health, 15(7), 844–854. doi:10.1080/13607863.2011.569481.

Acknowledgments

The data collection for this study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH57716) with supplemental support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the University of Michigan. The preparation of this manuscript was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging to Robert Joseph Taylor (P30AG1528).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, A.W., Chatters, L.M., Taylor, R.J. et al. Social Support from Family and Friends and Subjective Well-Being of Older African Americans. J Happiness Stud 17, 959–979 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9626-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9626-8