Abstract

We here present a rare case of development of a postoperative pancreatic fistula and breakdown of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis 8 months after pancreaticoduodenectomy. A 70-year-old man underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy for distal cholangiocarcinoma and initially recovered well. However, 8 months later, he developed abdominal pain and distention and was admitted to our institution with suspected pancreatitis. On the 17th day of hospitalization, he suddenly bled from the jejunal loop and a fluid collection was detected near the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis site. The fluid collection was drained percutaneously. Subsequent fistulography confirmed breakdown of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. Considering the patient's overall condition and the presence of postoperative adhesions, we decided to manage him conservatively. An additional drain tube was placed percutaneously from the site of the anastomotic breakdown into the lumen of the jejunum, along with the tube draining the fluid collection, creating a completely new fistula. This facilitated the flow of pancreatic fluid into the jejunum and was removed 192 days after placement. During a 6-month follow-up, there were no recurrences of pancreatitis or a pancreatic fistula. This case highlights the efficacy of percutaneous drainage and creation of an internal fistula as a management strategy for delayed pancreatic fistula and anastomotic breakdown following pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) has been performed for more than 100 years. It is associated with a complication rate between 40 and 55%. Reported surgical mortality rates range between 1 and 3% [1,2,3,4]. Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is a serious complication of PD that requires drainage or reoperation; reported incidence rates range from 10 to 20% [4,5,6,7,8]. Delayed POPF is rare, as most cases develop relatively soon after surgery. We report a patient who developed POPF and breakdown of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis (PJA) 8 months after surgery and was treated with percutaneous interventional drainage and internal fistulation.

Case report

A 70-year-old man with a remote history of rectal cancer resection presented with white stools from the colostomy and anorexia. His history was also notable for bowel obstruction owing to adhesions. He denied alcohol consumption and smoking. His height and weight were 173 cm and 52 kg, respectively. Body mass index was 17.3 kg/m2. Computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography (US), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and biopsy revealed a distal cholangiocarcinoma. On US, the main pancreatic duct (MPD) diameter was 2.1 mm. He underwent a subtotal stomach-preserving PD and Child reconstruction. The texture of the pancreas was soft during the operation. The PJA was performed in an end-to-side fashion using the modified Blumgart procedure with 4–0 polypropylene sutures; the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis was performed using 5–0 polydiaxone sutures. A 5 Fr pancreatic duct tube was inserted and fixed to the posterior wall and tunneled through the jejunal stump to the abdominal wall for an incomplete external fistula tube.

On postoperative day (POD) 5, the amylase level in the PJA drain was 742 U/L (three times above the upper limit of normal); however, it resolved spontaneously, resulting in a diagnosis of a biochemical leak [9, 10]. The drain was removed on postoperative day 8. The pancreatic duct tube was removed on POD 21 and the patient was discharged on POD 24. The final pathologic diagnosis was pT2N0M0 cholangiocarcinoma based on the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification of carcinoma of the distal extrahepatic bile duct [11]. The patient was followed without adjuvant chemotherapy administration. Three and 6 months after surgery, CT showed no abnormalities around the PJA or in the pancreatic parenchyma.

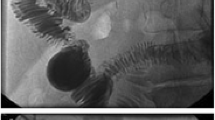

Eight months after surgery, the patient was complaining of abdominal pain and distention that worsened with eating. The patient’s serum amylase and C-reactive protein levels were 1019 U/L and 15.49 mg/dL, respectively. CT showed an accumulation of a large amount of ascitic fluid and mild dilatation of the MPD, but no local recurrence was apparent (Fig. 1a). He was admitted to the hospital with suspected pancreatitis. Although his symptoms improved with fasting alone, his serum amylase level increased again after resuming eating. We suspected the pancreatitis was caused by a PJA stricture and planned to perform endoscopic retrograde pancreatography to investigate. However, on the morning of the procedure (17 days after admission), he presented with fresh blood from the colostomy. CT showed bleeding from the stump of the jejunal loop near the PJA, a hematoma-like fluid collection at the PJA site, and increased volume of ascites fluid (Fig. 2a, b). Transcatheter arterial embolization was performed to control the bleeding and the ascites fluid was drained. The ascites fluid amylase level was remarkably high (6155 U/L). We suspected a problem with the PJA had caused a pancreatic fistula and consequent vascular collapse. The next day, transgastric drainage of the pancreatic duct was attempted with endoscopic ultrasonography guidance; however, it was abandoned, because the pancreatic duct diameter was too small. Double-balloon enteroscopy-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (DBE-ERCP) drainage and internal stenting were also considered. However, because transcatheter arterial embolization had recently been performed for bleeding from the stump of the jejunal loop, we were concerned about the increased risk of rebleeding by DBE-induced stress on the hemostasis site. Additionally, because 8 months had passed since surgery, we anticipated difficulties due to adhesions. Moreover, the patient’s physical status had significantly deteriorated, likely making him unable to endure a lengthy DBE procedure. Therefore, we decided to perform percutaneous drainage of the fluid collection adjacent to the PJA. The amylase level of the drainage fluid was 63,500 U/L and pancreatic fistula was diagnosed. Nine days after drainage tube placement, the drain was exchanged and fistulography was performed, which showed contrast in the MPD, jejunum, and fluid collection surrounding the anastomosis (Fig. 3a). This suggested destruction of the PJA. The patient's overall condition had significantly deteriorated, and considering the presence of adhesions and the elapsed 8 months since the surgery, surgical intervention was deemed extremely challenging. Therefore, the decision was made to pursue the establishment of a new pancreatic fluid outflow pathway through fistula formation. To create a new complete fistula, another 8.5 Fr internal tube [Dawson–Mueller (25 cm); Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA] was placed percutaneously into the jejunum from the area where the PJA had broken down via the fluid collection cavity (Fig. 3b, c). The patient’s symptoms were relieved and serum amylase level decreased after drainage. He was able to resume eating 23 days after the procedure. The size of the internal tube in the jejunum was gradually increased from 10 to 12 Fr to secure the fistula diameter. On day 48, fistulography confirmed that fistulation around the anastomosis was complete; no leakage into the abdominal cavity was observed. Therefore, the anastomosis drain was removed (Fig. 4a, b). The internal tube was clamped on day 76, making discharge possible. However, subsequent rehabilitation was necessary, and on day 18, the patient was transferred to another facility for rehabilitation. Continuous outpatient follow-up was maintained, and the internal tube was removed on day 202. Neither recurrence of pancreatitis nor pancreatic fistula has occurred in 6 months of follow-up.

Computed tomography findings at the onset of pancreatitis. Computed tomography findings 8 months after pancreatoduodenectomy were consistent with pancreatitis. a Ascites and mild dilatation of the main pancreatic duct (diameter, 3.3 mm; red arrow) were observed. b A 6 × 10 mm fluid collection was observed near the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis (yellow arrow)

Computed tomography findings at the time of bleeding from the colostomy. After the patient developed bleeding from the colostomy, computed tomography showed a bleeding from the stump of the jejunum loop (red arrow) as well as b an increase in size of the fluid collection near the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis (red circle). Moreover, the volume of ascites fluid had increased since admission

Fistulography findings. a Contrast in the main pancreatic duct (red arrow) and jejunum (yellow arrowhead) was contiguous with that in the fluid collection near the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. b An internal tube was inserted percutaneously into the jejunum via the fluid collection cavity. c Schema of treatment: (1) the fluid collection adjacent to the anastomosis was drained and (2) an internal tube with multiple side holes was inserted into the jejunum via the fluid collection to create a fistula

Fistulography at the time of internal tube removal. a Fistulography at the time of internal tube removal showed no leakage of contrast into the abdominal cavity. The main pancreatic duct (red arrow) and jejunum (yellow arrowhead) were filled with contrast, suggesting completion of a continuous fistula from around the anastomosis into the main pancreatic duct and jejunum. b Schema at the end of fistulation

Discussion

PD was first described by Kausch and popularized by Whipple, who developed the current technique [12]. It remains the standard procedure for surgical treatment of benign and malignant diseases involving the pancreatic head [13] and is one of the most difficult abdominal surgeries to perform. Reported complication rates, including major and minor, range from 40 to 55% [4,5,6,7]. POPF is a serious complication which can result in intra-abdominal bleeding, abscess, and sepsis. The International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) defines POPF as “fluid output of any measurable volume via an operatively placed drain with amylase activity greater than three times the upper normal serum value” and classifies it by grade; their definition does not mention the onset of POPF [9, 10]. Most cases of POPF occur within a few days or weeks of surgery. It rarely develops months later, as in our patient.

A search of the PubMed database using the terms 'late pancreatic fistula' and 'delayed pancreatic fistula' for articles published from 1947 to December 2022 that reported POPF occurring more than 6 months after surgery yielded six cases in five reports [14,15,16,17]. Table 1 shows these six cases as well as our own. The primary disease was cholangiocarcinoma in two cases and pancreatic head adenocarcinoma, ampullary adenocarcinoma, intraductal papillary mucinous adenoma, pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm, and solid pseudopapillary neoplasm in one, respectively. All patients underwent a standard PD with PJA. With the exception of one case [18], POPF onset was 6 months to 1 year after surgery and all patients reported epigastric pain. The cases with breakdown of the PJA were rare, with only two instances reported so far: one in Faraj's case that occurred 7 years postoperatively and the case presented in the current report. Notably, however, whereas the patient in the report by Faraj et al. [18] underwent treatment through a reoperation, an internal fistula management procedure was carried out in our patient, making it a distinctive aspect of our case.

Early POPF is a phenomenon in which pancreatic juice leaks from the cut end of the pancreas or the PJA before the anastomosis has stabilized, while delayed POPF is leakage which occurs after the anastomosis has stabilized. The delayed type may occur secondary to late complications other than anastomotic instability such as pancreaticojejunal/pancreaticogastric stricture and pancreatitis [19].

In all seven cases of delayed POPF, the patient experienced abdominal pain and a fluid collection was found near the anastomosis. Pancreatitis developed for some reason, which resulted in destruction of the small pancreatic ducts and leakage of pancreatic juice near the anastomosis. The incidence of pancreatitis more than 90 days after PD ranges from 4.3 to 5.7% [20, 21]. The onset of pancreatitis after PD is thought to be caused by an increase in pancreatic ductal pressure owing to a PJA stricture. Yen et al. reported that 15 of 23 patients with delayed pancreatitis after PD had a PJA stricture and that PJA stricture was a significant predictor of pancreatitis [20]. Among the previously reported cases of delayed POPF, one was associated with pancreatitis from the anastomotic stricture [15]. However, pancreatitis can develop without an anastomotic stricture, although the underlying pathogenic mechanism is not clear. In the previously reported cases, the anastomotic site was not assessed or had already failed, so it is possible that the pancreatitis was not caused by a stricture. However, assessment of the anastomotic site is necessary, as is early intervention.

PJA stricture presents with acute or chronic pancreatitis and occurs in 1.4–11.4% of PDs [22,23,24]. Patients with a history of early POPF, those receiving chemotherapy, and patients whose primary disease is chronic pancreatitis have a higher risk of stricture [24,25,26]. The size of the MPD has been significantly associated with pancreatitis incidence; however, the relationship with stenosis has not been proven [20]. It is not clear whether pancreas texture or surgical techniques, such as anastomosis method or type of suture used, are associated with delayed pancreatitis and anastomotic stricture. However, the pancreas texture was reportedly soft in five of the six cases we reviewed. When pancreatitis occurs, endoscopic treatment or surgical re-anastomosis is commonly performed in symptomatic patients; however, the timing of intervention varies between institutions and surgeons. In one report, the median time to treatment was 5 months (range 0–49) [25]. The timing of intervention for anastomotic stricture is controversial, as it depends on the severity of symptoms and other factors.

The onset of POPF in our patient was probably caused by pancreatitis, which induced a fistula at the pancreatic stump, leading to anastomosis failure. Although the pancreatic fluid temporarily remained at the anastomosis site owing to surrounding adhesions, it gradually dispersed throughout the abdomen. In retrospect, CT performed 8 months after surgery when pancreatitis was diagnosed showed a small fluid collection near the anastomosis site. In addition, the MPD diameter was slightly larger than before surgery, indicating that the pancreatitis was probably caused by a PJA stricture (Fig. 1b). When the PJA breakdown was discovered 17 days later, the fluid collection had increased and a large amount of ascites fluid was observed. We believe that this fluid collection gradually became confined within a narrow space because of the surrounding adhesions and the high concentration of pancreatic fluid, which caused an increase in internal pressure over the next 17 days and ultimately led to breakdown. The situation in this case may have been different if, upon admission, the patient had undergone early intervention for PJA stenosis (e.g., DBE-ERCP or endoscopic ultrasonography-guided pancreatic duct drainage) or careful monitoring of changes in the size of fluid collections around the pancreaticojejunostomy. At the very least, it is highly likely that the anastomotic breakdown could have been avoided. Even when the anastomosis appears to have stabilized several months after surgery, it is essential to consider early and proactive treatment for complications related to the pancreas, given the important role of this organ in digestion. We want to emphasize that the occurrence of delayed PJA breakdown, a significant complication that has not been previously reported, is a possibility that should be recognized.

If the PJA stricture was treated endoscopically or the fluid collection drained at the time of admission, the patient’s outcome may have been substantially different.

The treatment options for delayed POPF are percutaneous drainage, endoscopic treatment, and surgery. Pancreatic fistula alone can be treated with drainage alone; however, treatment can be difficult if the PJA is disrupted. In general, PJA breakdown in the early postoperative period can be treated endoscopically or with surgery (e.g., pancreaticojejunal anastomosis resection or fistulojejunal anastomosis) [27]. Total pancreatectomy can be considered in life-threatening emergencies, but it is associated with high mortality [28,29,30]. In our patient, surgical reconstruction of the PJA was considered when anastomosis breakdown was discovered; however, it was deemed challenging due to the patient’s poor overall condition and the presence of postoperative adhesions, pancreatitis, pancreatic fistula, and pancreatic ascites. Although total pancreatectomy was another option, we elected to proceed with conservative treatment to preserve the pancreas as much as possible and because it was not an emergency situation. The management of PJA complications typically starts with consideration of conservative treatment options such as endoscopic drainage (e.g., endoscopic ultrasonography-guided pancreatic duct drainage or DBE-ERCP). In this case, endoscopic ultrasonography-guided pancreatic duct drainage was attempted but proved to be challenging. Similarly, approaching the pancreaticojejunostomy site through DBE-ERCP was contemplated, but ERCP is technically challenging in patients with a surgically altered anatomy of the upper gastrointestinal tract, such as patients who have undergone PD. A recent report indicated an 84% success rate of DBE-ERCP for addressing issues in the biliary and pancreatic ducts among patients with postoperative gastrointestinal tract alterations [31]. However, when considering the approach to the pancreatic duct alone, the pancreaticojejunostomy site often aligns with the endoscope, making the procedure more technically challenging. This results in a slightly lower treatment success rate, reported as 68.3% in one study [32]. Moreover, the procedure also becomes challenging in patients with severe adhesions. In the present case, we decided to forgo DBE-ERCP because of the surgical timing (the recent bleeding from the stump of the jejunal loop as well as the 8-month postoperative period, leading us to anticipate severe adhesions) and the patient’s compromised overall health condition. Instead, we chose to prioritize the percutaneous approach. Accordingly, for the drainage, an internal tube was placed in the jejunum to maintain jejunum–MPD continuity for a long period of time to enable complete fistulation. The flow of pancreatic juice was re-established by forming a flow pathway from the MPD to the jejunum via the surrounding fistula and was successful. In cases of delayed POPF, unlike early POPF, adhesions have developed around the PJA; therefore, the associated fluid collection should be localized. Delayed POPF associated with PJA breakdown can be treated conservatively.

We were able to achieve success with this treatment, but it remained challenging. Other options might have also been considered, such as waiting for the patient’s overall condition to improve before attempting DBE-ERCP or performing direct percutaneous puncture of a suitable bowel segment for access to the PJA. In any patient, it is essential to assess the priority of various treatment approaches, attempt them sequentially, and be prepared for the possibility that surgery may ultimately be necessary.

Prompt intervention is necessary when late-onset pancreatitis is diagnosed after PD and a fluid collection is detected at the anastomosis site, which suggests POPF. We experienced a patient with a delayed POPF who was treated percutaneously with drainage and tube placement for fistulation of the pancreatic duct and jejunum.

Abbreviations

- POPF:

-

Postoperative pancreatic fistula

- PD:

-

Pancreaticoduodenectomy

- PJA:

-

Pancreaticojejunal anastomosis

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- US:

-

Ultrasonography

- MPD:

-

Main pancreatic duct

- POD:

-

Postoperative day

- DBE-ERCP:

-

Double-balloon enteroscopy-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

References

Büchler MW, Wagner M, Schmied BM, et al. Changes in morbidity after pancreatic resection: toward the end of completion pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1310–4.

Kimura W, Miyata H, Gotoh M, et al. A pancreaticoduodenectomy risk model derived from 8575 cases from a national single-race population (Japanese) using a web-based data entry system: the 30-day and in-hospital mortality rates for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2014;259:773–80.

Cameron JL, He J. Two thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:530–6.

McMillan MT, Soi S, Asbun HJ, et al. Risk-adjusted outcomes of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula following pancreatoduodenectomy: a model for performance evaluation. Ann Surg. 2016;264:344–52.

Veillette G, Dominguez I, Ferrone C, et al. Implications and management of pancreatic fistulas following pancreaticoduodenectomy: the Massachusetts General Hospital experience. Arch Surg. 2008;143:476–81.

Kokkinakis S, Kritsotalis EI, Maliotis N, et al. Complications of modern pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2022;21:527–37.

Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Giuliani T, et al. Pancreatoduodenectomy at the verona pancreas institute: the evolution of indications, surgical techniques, and outcomes: a retrospective analysis of 3000 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2022;276:1029–38.

Ellis RJ, Brock Hewitt D, Liu JB, et al. Preoperative risk evaluation for pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2019;119:1128–34.

Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, et al. International study group on pancreatic fistula definition. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13.

Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, et al. International study group on pancreatic surgery (ISGPS). The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery. 2017;161:584–91.

Liao X, Zhang D. The 8th edition American joint committee on cancer staging for hepato-pancreato-biliary cancer: a review and update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;145:543–53.

Whipple AO, Parsons WB, Mullins CR. Treatment of carcinoma of the ampulla of vater. Ann Surg. 1935;102:763–79.

Hackert T, Klaiber U, Pausch T, et al. Fifty years of surgery for pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2020;49:1005–13.

Ito Y, Irino T, Egawa T, et al. Delayed pancreatic fistula after ancreaticoduodenectomy. A case report. JOP. 2011;12:410–2.

Perez NP Jr, Forcione DG, Ferrone CR. Late pancreatic fistula after Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Pancreat Cancer. 2016;2:65–70.

Jena SS, Meher D, Ranjan R. Delayed pancreatic fistula: An unaccustomed complication following pancreaticoduodenectomy—a rare case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;66: 102460.

Yamamoto M, Zaima M, Yazawa T, et al. Redo pancreaticojejunal anastomosis for late-onset complete pancreaticocutaneous fistula after pancreaticojejunostomy. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:223.

Faraj W, Abou Zahr Z, Mukherji D, Zaghal A, Khalife M. Pancreatic anastomosis disruption seven years postpancreaticoduodenectomy. Case Rep Med. 2010;2010: 436739.

Brown JA, Zenati MS, Simmons RL, et al. Long-term surgical complications after pancreatoduodenectomy: incidence, outcomes, and risk factors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:1581–9.

Yen HH, Ho TW, Wu CH, et al. Late acute pancreatitis after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, outcome, and risk factors. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2019;26:109–16.

Nabeshima T, Kanno A, Masamune A, et al. Successful endoscopic treatment of severe pancreaticojejunostomy strictures by puncturing the anastomotic site with an EUS-guided guidewire. Intern Med. 2018;57:357–62.

Reid-Lombardo KM, Ramos-De la Medina A, Thomsen K, et al. Long-term anastomotic complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy for benign diseases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1704–11.

Zarzavadjian Le Bian A, Cesaretti M, Tabchouri N, et al. Late pancreatic anastomosis stricture following pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:2021–8.

Aran Demirjian AN, Kent TS, Callery MP, et al. The inconsistent nature of symptomatic pancreatico-jejunostomy anastomotic strictures. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:482–7.

Cioffi JL, McDuffie LA, Roch AM, et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy stricture after pancreatoduodenectomy: outcomes after operative revision. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:293–9.

Morgan KA, Fontenot BB, Harvey NR, et al. Revision of anastomotic stenosis after pancreatic head resection for chronic pancreatitis: is it futile? HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:211–6.

Alexakis N, Sutton R, Neoptolemos JP. Surgical treatment of pancreatic fistula. Dig Surg. 2004;21:262–74.

Smith CD, Sarr MG, vanHeerden JA. Completion pancreatectomy following pancreaticoduodenectomy: clinical experience. World J Surg. 1992;16:521–4.

Torres OJM, Moraes-Junior JMA, Fernandes ESM, et al. Surgical management of postoperative grade C pancreatic fistula following pancreatoduodenectomy. Visc Med. 2022;38:233–42.

Kawakatsu S, Kaneoka Y, Maeda A, et al. Salvage anastomosis for postoperative chronic pancreatic fistula. Updates Surg. 2016;68:413–7.

Farina E, Cantù P, Cavallaro F, et al. Effectiveness of double-balloon enteroscopy-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (DBE-ERCP): a multicenter real-world study. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55:394–9.

Kogure H, Sato T, Nakai Y, et al. Endoscopic management of pancreatic diseases in patients with surgically altered anatomy: clinical outcomes of combination of double-balloon endoscopy- and endoscopic ultrasound-guided interventions. Dig Endosc. 2021;33:441–50.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Suzuki, R., Konishi, Y., Makino, K. et al. Treatment of delayed pancreatic fistula associated with anastomosis breakdown after pancreaticoduodenectomy using percutaneous interventions. Clin J Gastroenterol 17, 356–362 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-023-01900-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-023-01900-z