Abstract

Introduction

Cancer interferes with participation in valued lifestyle activities (illness intrusiveness) throughout post-treatment survivorship. We investigated whether illness intrusiveness differs across life domains among survivors with diverse cancers. Intrusiveness should be highest in activities requiring physical/cognitive functioning (instrumental domain). Intrusiveness into relationship/sexual functioning (intimacy domain) should be higher in prostate, breast, and gastrointestinal cancers than in others.

Methods

Cancer outpatients (N = 656; 51% men) completed the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale (IIRS) during follow-up. We compared IIRS Instrumental, Intimacy, and Relationships and Personal Development [RPD] subscale and total scores across gastrointestinal, lung, lymphoma, head and neck, prostate (men), and breast cancers (women), comparing men and women separately.

Results

Instrumental subscale scores (Mmen = 3.05–3.80, Mwomen = 3.02–3.63) were highest for all groups, except prostate cancer. Men with prostate cancer scored higher on Intimacy (M = 3.40) than Instrumental (M = 2.48) or RPD (M = 1.59), p’s < .05; their Intimacy scores did not differ from men with gastrointestinal or lung cancer. Women collectively showed higher Instrumental (M = 3.39) than Intimacy (M = 2.49) or RPD scores (M = 2.27), p’s < .001, but not the hypothesized group difference in Intimacy.

Conclusions

Post-treatment survivors continue to experience some long-term interference with activities requiring physical and cognitive functioning. Sexual adjustment may be of special concern to men when treatments involve genitourinary functioning.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Ongoing monitoring with the IIRS to detect lifestyle interference throughout survivorship may enhance quality of life. Screening and intervention should target particular life domains rather than global interference.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

After cancer treatment has been completed successfully, many survivors report ongoing limitations that compromise their sense of well-being [1–3]. Research concerning health-related quality of life during cancer survivorship largely focuses on short- and long-term biomedical outcomes (e.g., fatigue, pain, sleep disorders, neurocognitive changes, and symptom burden) [3–8]), but these introduce additional stress to the extent that they render it more difficult for cancer survivors to remain actively involved in the activities and pursuits that give purpose and meaning to life, a phenomenon we termed illness intrusiveness [9].

The central premise of the illness intrusiveness theoretical framework (Fig. 1) theorizes that disease and treatment factors (e.g., lingering side effects) interfere with the capacity to continue engaging in valued activities (e.g., work; recreation; familial, couple, and social relationships), thereby reducing subjective well-being and inducing emotional distress [10]. Illness intrusiveness likely reflects a powerful determinant of subjective well-being following cancer treatment: survivors report ongoing challenges in regaining pre-morbid employment and financial status [11–13], social life [13, 14], family and other relationships [8, 11, 15], and sex life [13, 16–18]. These normal spheres of activity are essential to personal and social identity and to self-esteem, including during and after the cancer experience [19, 20]. When people encounter difficulties in resuming such activities, they experience distress as well as other negative psychological consequences, such as feeling as if one is a burden on others, stigma, compromised self-concept, reduced self-esteem [13, 21–23], disappointment with treatment outcomes because of limitations [23], and poorer overall quality of life [24, 25].

The central premise of the illness intrusiveness theoretical framework. Disease and treatment effects interfere with the capacity to engage in valued activities and interests (illness intrusiveness), which, in turn, adversely affects subjective well-being. The Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale Illness measures intrusiveness into three life domains—Instrumental, Intimacy, and Relationships and Personal Development

Studies of illness intrusiveness in cancer have mostly examined illness intrusiveness globally [21, 26, 27]. Because cancer is a heterogeneous category of diseases, however, difficulties in re-engaging in activities may vary depending on the affected anatomical site and/or treatment effects. People with different types of cancer and those who receive different cancer treatments may report similar intensities of emotional distress, but the factors responsible for the experienced level of stress may differ as a function of the biomedical consequences specific to their disease and treatment. By identifying distinct lifestyle domains (e.g., types of activities) that are differentially vulnerable to such disruptions, it may be possible to characterize particular cancers or treatments in terms of their associated illness-intrusiveness disruptions.

Cancer and cancer treatments have yet to be compared in terms of their impact on illness intrusiveness into distinct life domains. Cancer survivors often report long-term declines in physical functioning [8, 28] . Thus, for most cancers, the overriding impact of illness intrusiveness likely involves activities that require intact physical and cognitive functioning, such as work and active recreation [12, 29, 30].

Some cancers and their treatments involve sites with direct physiological or psychological associations to sexuality and may, therefore, greatly affect sexual functioning and couple adjustment. In men with prostate cancer [18, 31–33] or certain gastrointestinal cancers [13, 34, 35], treatments can produce erectile and/or ejaculatory dysfunction due to pelvic-nerve damage, which, in turn, impacts satisfaction with sex life, relationship adjustment, and sexual self-image. Hence, difficulties with sexual and couple functioning are likely more salient to men with these cancer types than to men with cancers that do not affect genitourinary functioning. Similarly, sexual and couple functioning can be affected in women with breast [16, 36, 37] and gastrointestinal cancers [13, 34], although not as consistently as in men with prostate cancer [38–40]. Women with breast and gastrointestinal cancers may report greater interference with sexual and couple functioning than women with cancers that do not impinge so directly on sexuality.

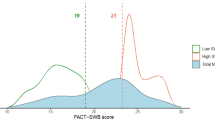

The current study compares illness intrusiveness across different domains of activity among survivors of gastrointestinal, head and neck, lymphoma, lung, prostate (men only), and breast (women only) cancer. We conducted the comparisons separately in men and women because the sexes respond differently depending on whether the affected life domain is central to their roles (e.g., work for men, relationships and nurturance for women) [41, 42]. We employed the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale (IIRS) [9], a self-report instrument that measures illness-induced interference with three general domains of life experience: (a) Instrumental—work, active recreation, financial situation, and health; (b) Intimacy—relationship with one’s spouse and sex life; and (c) Relationships and Personal Development—family relations, other social relations, self-expression, religious expression, community/civic involvements, and passive recreation [43].

We hypothesized that (1) most survivors would report the highest illness intrusiveness on the Instrumental subscale (i.e., activities requiring physical and cognitive functioning); (2) men with prostate and gastrointestinal cancers would report greater intrusiveness on the Intimacy subscale (i.e., sexual and couple functioning) than men with cancers that do not affect sexual functioning directly (head and neck, lymphoma, and lung cancers); and, correspondingly, (3) women with breast and gastrointestinal cancers would report greater Intimacy-related intrusiveness than women whose cancers do not affect sexual functioning directly.

Methods

Participants

Between July 2000 and July 2001, we recruited a sample of cancer patients who had completed active treatment and were attending outpatient clinics at Princess Margaret Hospital, a comprehensive cancer center in Toronto, for a study concerning satisfaction with the physician-patient interaction [44]. The study afforded the opportunity for a secondary analysis of reported illness intrusiveness in men and women with cancer. Equal numbers of women and men across six common cancer diagnoses were sampled: gastrointestinal, head and neck, lymphoma, lung, prostate (men only), and breast cancer (women only). Inclusion criteria included fluency in English and attendance at the clinic for post-treatment follow-up. Research assistants approached patients about the study as they awaited routine follow-up appointments with their oncologists.

A total of 699 participants (349 men, 350 women) completed the questionnaires. Unfortunately, response rate was not documented. We restricted analyses to data from respondents who provided responses for at least 75% of the items within each IIRS subscale, to reduce the impact of missing data. The final sample for analysis comprised 656 respondents (335 men, 321 women; 93.8% of the initial participants); of these 656 respondents, 95% of the men and 98% of the women had no missing data. We imputed missing data by prorating. As compared to the final sample, the 43 excluded respondents were more likely to be female (67.4% vs. 48.9%), χ2 (1, N = 699) = 5.53, p = .02. They were less likely to be married (37.2% vs. 72.8%), χ2 (4, N = 697) = 42.66, p < .001, or working for pay (22.0% vs. 44.2%), χ2 (5, N = 693) = 11.64, p = .04. Included and excluded respondents did not differ in educational level, diagnosis, or tumor severity.

Table 1 summarizes the final sample’s sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Most participants were married, had achieved high school to college education, and approximately half were still working for pay. Approximately half had no evidence of disease . Most had been diagnosed 3–6 years earlier. Significant differences were observed across cancer types in age, occupation, time since diagnosis, and tumor status. These variables were thus controlled statistically in all analyses.

Materials

The questionnaire package included the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale (IIRS) [9], a 13-item self-report instrument in which respondents rate the extent to which “illness and/or its treatment” interfere with each of 13 life domains central to quality of life, using a 7-point rating scale (1 = “Not Very Much”, 7 = “Very Much”). A total score is calculated as the sum of all 13 item ratings. The IIRS has demonstrated strong psychometric properties across diverse chronic-disease [45–47] and cancer groups [17, 21, 26, 30] (see [48] for review). The IIRS generates three subscales that include 12 of the 13 items: Instrumental (work, financial situation, active recreation, and health items), Intimacy (relationship with spouse and sex life items), and Relationships and Personal Development (family relations, other social relationships, self-expression, religious expression, community/civic involvements, and passive recreation items) [43, 49] . The diet item did not represent one subscale uniquely [43] and so is excluded. Subscale scores consist of the mean ratings of the items included in a subscale. Higher scores thus indicate greater illness intrusiveness (i.e., more extensive interference with activities).

Sociodemographic and medical information was documented for descriptive and statistical-control purposes, using a self-report questionnaire developed for this study.

Procedure

The hospital’s Research Ethics Board approved the study. A research assistant approached people with cancer while they awaited routine follow-up clinic appointments. Individuals who met eligibility criteria received an introductory letter explaining the purpose of the study, participation requirements, and assuring anonymity and confidentiality. Those who volunteered provided informed consent before completing the questionnaires independently while awaiting their oncologists.

Statistical analyses

We calculated internal consistency reliability for the IIRS Total and subscale scores using Cronbach’s alpha. We calculated separate coefficients for each of the Cancer Type x Sex groups.

We tested the hypothesis that illness intrusiveness subscales would differ across cancer types using 2-way mixed Analyses of Covariance (ANCOVAs), with Cancer Type as the between-groups factor and IIRS Subscale as the within-groups factor. We conducted separate analyses for each sex. To compare the effect of cancer type on the IIRS Total Score, we conducted separate 1-way between-subjects ANCOVAs on the IIRS Total Score for each sex, with Cancer Type as the between-groups factor and IIRS Total Score as the dependent variable.

Covariates

For all IIRS subscale- and total-score analyses, age, occupation, time since diagnosis, and tumor status (no evidence of disease, localized disease, or metastatic disease) were controlled as covariates. In addition, between-subjects ANOVAs were conducted on the remaining sociodemographic variables (sex, marital status, and education) to identify those significantly associated with each of the IIRS domain subscales (p < .05). A significant effect of marital status was observed for all three IIRS domains, p’s < .01; thus, marital status was added as a covariate for all analyses.

Results

Reliability (internal consistency) of the IIRS

Table 2 reports internal consistency estimates for all Sex x Cancer Type groups. Estimates for the IIRS Total and the Instrumental and Relationships and Personal Development subscales met the criterion of good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ≥ .70 [50] across all groups, alphas = .78 to .93. For the Intimacy subscale, Cronbach’s alpha was .40 for the Prostate group and ranged from .60 to .88 for the remaining Sex x Cancer Type groups.

Comparing illness intrusiveness across cancer types

Men with cancer

The 2-way (Cancer Type x IIRS Subscale) mixed ANCOVA indicated a significant Cancer Type x IIRS Subscale interaction, F(8, 496) = 6.97, p < .001. Table 1 reports mean IIRS subscale scores, adjusted for covariates; these are plotted in Fig. 2. Significant pairwise differences (p < .05) were identified post-hoc by determining whether (a) within each cancer type, adjusted mean subscale scores fell outside the 95% confidence intervals of the other subscales and (b) adjusted mean scores of a subscale for one cancer type fell outside the 95% confidence intervals for the same subscale for the other types.

Comparison of IIRS subscale scores across men with different cancer types, with confidence intervals formed by the standard errors. Mean IIRS subscale scores, adjusted for covariates, are indicated for each group. Within each cancer type, IIRS subscales marked with different letters (a–c) were significantly different, p < .05

The first hypothesis, that all people with cancer will report the highest illness intrusiveness in the Instrumental domain, received partial support in men. As apparent in Fig. 2, Instrumental intrusiveness was highest of all three subscale scores for all cancer types, except prostate cancer. Relationships and Personal Development scores were the lowest for all cancer types. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that for all cancer groups, including prostate cancer, Instrumental scores were always significantly higher than Relationships and Personal Development scores, p < .05 (see Fig. 2). For head and neck and lung cancers, Instrumental scores were significantly higher than Intimacy scores, but Intimacy did not differ significantly from Relationships and Personal Development. For lymphoma and gastrointestinal cancers, on the other hand, Instrumental and Intimacy scores did not differ significantly, whereas Intimacy scores were significantly higher than Relationships and Personal Development scores.

The second hypothesis, that those with cancers that are more likely to affect sexuality and sexual functioning will report greater illness intrusiveness into Intimacy than those with other cancers, also received partial support in men. As evident in Fig. 2, Intimacy was the highest IIRS subscale score for prostate cancer, and it was significantly higher than both of the other subscale scores, p < .05. The prostate cancer group’s Intimacy score was also significantly higher than those for the male lymphoma and head and neck cancer groups, p < .05, but although it was also higher than the Intimacy scores for the gastrointestinal and lung cancer groups, differences were not statistically significant. Similarly, lung cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, and lymphoma did not differ significantly on Intimacy scores, but the gastrointestinal group did report significantly higher Intimacy disruption than the head and neck cancer group, p < .05.

Because of the relatively low reliability observed for Intimacy in the prostate cancer group (and male groups in general), a secondary analysis comparing the two Intimacy item scores was conducted for that group. A paired t-test indicated that for the prostate cancer group, the mean score for sex life, M = 4.28, SD = 2.47, was significantly higher than that for relationship with spouse, M = 2.31, SD = 1.80, t(118) = 8.09, p < .001. Similar analyses conducted with the other male cancer groups, to provide a context for interpreting this observation in prostate cancer, showed similar, but less extreme differences (in descending order of significance of difference): for gastrointestinal, Msex life = 3.57, SD = 2.41 versus Mrelationship with spouse = 2.72, SD = 2.17, t(52) = 2.87, p = .01; for head and neck, Msex life = 2.64, SD = 1.94 versus Mrelationship with spouse = 1.96, SD = 1.44, t(52) = 2.77, p = .01; for lung, Msex life = 3.30, SD = 2.51 versus Mrelationship with spouse = 2.40, SD = 2.01, t(56) = 2.53, p = .02; and for lymphoma, Msex life = 2.84, SD = 2.23 versus Mrelationship with spouse = 2.37, SD = 1.85, t(56) = 1.73, p = .09.

When we conducted the 1-way (Cancer Type) between-subjects ANCOVA for IIRS Total scores, results indicated a significant Cancer Type main effect in men, F(4, 248) = 3.66, p = .01. Table 1 presents adjusted total scores for each cancer group. The prostate cancer group reported the lowest mean Total score, whereas the lung cancer group reported the highest. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that the prostate cancer group reported significantly lower IIRS Total scores, M = 28.56, SE = 1.76, than the gastrointestinal cancer, M = 36.63, SE = 2.30, p = .01, and lung cancer groups, M = 39.00, SE = 2.60, p = .001. No other significant group differences were evident.

Women with cancer

The 2-way (Cancer Type x IIRS Subscale) mixed ANCOVA showed only a significant IIRS Subscale main effect, F(2, 474) = 4.39, p = .01; there was no significant Cancer Type main effect or Cancer Type x IIRS Subscale interaction effect. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons across subscale scores indicated that illness intrusiveness differed significantly across all three subscales, p’s < .05 to <.001. As hypothesized, women with cancer reported the highest score in the Instrumental subscale, M = 3.39, SE = .11, which differed significantly from both the Intimacy, M = 2.49, SE = .11, p < .001, and Relationships and Personal Development subscales, M = 2.27, SE = .09, p < .001. The latter two also differed significantly, p = .03, but hypothesized differences on the Intimacy subscale between breast and gastrointestinal cancers and other cancers were not observed.

The 1-way (Cancer Type) between-subjects ANCOVA on the IIRS Total score did not yield a significant Cancer Type main effect in women, F(4, 237) = 1.40, p = .23. Table 1 presents the adjusted total scores for each cancer group.

Discussion

As hypothesized, many men and women continue to experience cancer-related lifestyle interference to some degree long after the completion of cancer treatment; these effects are most pronounced when activities require physical and cognitive performance. This is consistent with other observations that ongoing side effects compromise physical and cognitive functioning [8, 28], but especially physical functioning [12], and this interferes with continued participation in activities that rely on such capacities [11, 13, 14, 29]. Thus, a number of long-term survivors continue to require medical management of side effects and other interventions to facilitate rehabilitation well after cancer treatment has concluded. The domain of employment would seem especially important to address because of its importance to identity, self-esteem, and life satisfaction [19, 51]. Difficulties in resuming employment during the period of long-term survivorship may also exacerbate the financial toll imposed by cancer treatment and by the unemployment often imposed on people while they undergo cancer [25, 52].

Prostate cancer survivors appear to be the exception, reporting less disruption in the Instrumental domain as compared to other aspects of life. This group may recover physical functioning more quickly than people with other cancers [53]. As expected, however, prostate cancer survivors reported more illness intrusiveness into Intimacy than men with lymphoma or head and neck cancer; they did not differ, however, from men with gastrointestinal or lung cancer. As hypothesized, men with gastrointestinal cancer also reported high illness intrusiveness into the Intimacy life domain but differed significantly only from men with head and neck cancer. These findings are consistent with numerous reports that iatrogenic neurovascular damage compromises erectile and ejaculatory functioning, sexual sensation, and satisfaction in prostate cancer [18, 31–33], and consequently compromises relationship adjustment and quality of life [18, 33, 54]. Male gastrointestinal cancer survivors similarly experience sexual dysfunctions due to pelvic-nerve damage, but also due to embarrassment about incontinence, odor and having an ostomy and ostomy appliance [13, 34, 35, 55]. In lung and, in fact, other cancer groups [56], psychological factors, like changes in appearance, self-perceived attractiveness [57], and mood [58], may contribute more strongly to reported sexual difficulties than physiological factors [56]. Sexual and relationship functioning are central to quality of life [59–61], and so these issues should receive high priority during routine follow-up assessment. Physiological changes and changes in self-perceptions should both be investigated as contributors to sexual dysfunction [56].

Like their male counterparts, women with cancer reported the expected dominance of illness intrusiveness into Instrumental as compared to other life domains. Unlike men with prostate or gastrointestinal cancer, however, women with breast or gastrointestinal cancer did not differ from women with other cancer types in reported illness intrusiveness into Intimacy. Some studies have noted sexual dysfunctions and decreased libido in breast cancer survivors, particularly in those treated with chemotherapy [16, 37, 62], but others have not [63]. The nature and prevalence of sexual dysfunctions in gastrointestinal cancers are similarly less clear in women than in men [35, 64, 65]. However, intimacy issues should not be ignored in these groups because treatment sequelae such as loss of the breast(s), vaginal dryness, and dyspareunia can cause sexual difficulties and dissatisfaction [37]. It is crucial to realize that survivors may also be reluctant to report these distressing concerns. Sexual issues should be normalized through routine assessment, and appropriate medical and/or sex therapy initiated when indicated.

Overall, the separate IIRS subscales provide useful incremental information about psychosocial functioning over the IIRS total score. Men with prostate cancer reported the lowest total score of all male groups, but this obscures the specific adverse impact on intimacy. Total scores also mask the fact that the Instrumental domain is the most adversely affected domain and hence requires more urgent clinical attention in most cancer survivors. Hence, use of the subscale scores can provide a highly useful targeted screen in follow-up psychosocial assessments.

In terms of limitations, our respondent sample comprised outpatients with varied characteristics. This accurately reflects the diversity of clinical cohorts, but sample heterogeneity may affect the validity of group comparisons. We controlled statistically for group differences in background characteristics and for characteristics relating to illness intrusiveness, but findings nevertheless should be interpreted with caution and require replication. The relatively small subsample sizes, which may affect the power to detect group differences, also call for cross-validation with larger groups. Since participation rates were not recorded, representativeness is uncertain. However, healthier, less distressed individuals are more likely volunteer for studies [66]. Hence, our findings may both be more representative of such survivors and suggest that others may be worse off and in even more need of assessment and intervention. Regardless of the absolute representativeness of the patient groups, the fact cannot be ignored that a sizeable number of long-term cancer survivors (>650 people) reported at least some ongoing interference with lifestyles activities and interests after treatment completion.

Other limitations include the caveat that causal priorities cannot be established due to the cross-sectional design. Finally, that individual scores on the two Intimacy-subscale items differed significantly in most male cancer groups, especially in prostate cancer, suggests that sexual and couple functioning may not always be disturbed to the same degree [67]. For certain groups, then (e.g., prostate cancer), separate clinical assessment of sexual and relationship adjustment may be warranted.

Cancer survivors who expect (or are expected) to resume “normal” lives following treatment may require more rehabilitative assistance than previously recognized. Patient-centered care and ongoing monitoring of participation in valued activities can help to redress quality-of-life concerns during long-term survivorship. Rehabilitative interventions can then be targeted to the concerns most likely to be associated with a specific cancer and/or treatment. The IIRS offers a brief, simple, and valid tool to screen for domain-specific lifestyle disruptions throughout survivorship and to evaluate the benefits of rehabilitative interventions.

References

Lo C, Li M, Rodin G. The assessment and treatment of distress in cancer patients: overview and future directions. Minerva Psichiatr. 2008;49:129–43.

Lynch BM, Steginga SK, Hawkes AL, Pakenham KI, Dunn J. Describing and predicting psychological distress after colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:1363–70.

Vahdaninia M, Omidvari S, Montazeri A. What do predict anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients? A follow-up study. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:355–61.

Ahlberg K, Ekman T, Wallgren A, Gaston-Johansson F. Fatigue, psychological distress, coping and quality of life in patients with uterine cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45:205–13.

Burkett VS, Cleeland CS. Symptom burden in cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:167–75.

Chin D, Boyle GM, Porceddu S, Theile DR, Parsons PG, Coman WB. Head and neck cancer: past, present and future. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:1111–8.

Delgado-Guay MO, Bruera E. Management of pain in the older person with cancer. Oncology. 2008;22:56–61.

Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, Jean-Pierre P, Morrow GR. Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist. 2007;12 Suppl 1:4–10.

Devins GM, Binik YM, Hutchinson TA, Hollomby DJ, Barre PE, Guttmann RD. The emotional impact of end-stage renal disease: importance of patients’ perceptions of intrusiveness and control. Int J Psychiatr Med. 1983;13:327–43.

Devins GM. Illness intrusiveness and the psychosocial impact of lifestyle disruptions in chronic life-threatening disease. Adv Ren Repl Ther. 1994;1:251–63.

Ashing-Giwa KT, Kagawa-Singer M, Padilla GV, Tejero JS, Hsiao E, Chhabra R, et al. The impact of cervical cancer and dysplasia: a qualitative, multiethnic study. Psycho Oncol. 2004;13:709–28.

Oberst K, Bradley CJ, Gardiner JC, Schenk M, Given CW. Work task disability in employed breast and prostate cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:322–30.

Rozmovits L, Ziebland S. Expressions of loss of adulthood in the narratives of people with colorectal cancer. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:187–203.

Vironen JH, Kairaluoma M, Aalto AM, Kellokumpu IH. Impact of functional results on quality of life after rectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:568–78.

Heinonen H, Volin L, Zevon MA, Uutela A, Barrick C, Ruutu T. Stress among allogeneic bone marrow transplantation patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:62–71.

Alder J, Zanetti R, Wight E, Urech C, Fink N, Bitzer J. Sexual dysfunction after premenopausal Stage I and II breast cancer: do androgens play a role? J Sex Med. 2008;5:1898–906.

DeGroot JM, Mah K, Fyles A, Winton S, Greenwood S, DePetrillo AD, et al. The psychosocial impact of cervical cancer among affected women and their partners. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:918–25.

Neese LE, Schover LR, Klein EA, Zippe C, Kupelian PA. Finding help for sexual problems after prostate cancer treatment: a phone survey of men’s and women’s perspectives. Psycho Oncol. 2003;12:463–73.

Feuerstein M, Todd BL, Moskowitz MC, Bruns GL, Stoler MR, Nassif T, et al. Work in cancer survivors: a model for practice and research. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:415–37.

Rasmussen DM, Elverdam B. The meaning of work and working life after cancer: an interview study. Psycho Oncol. 2008;17:1232–8.

Beanlands HJ, Lipton JH, McCay EA, Schimmer AD, Elliott ME, Messner HA, et al. Self-concept as a “BMT patient”, illness intrusiveness, and engulfment in allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:419–25.

Devins GM, Stam HJ, Koopmans JP. Psychosocial impact of laryngectomy mediated by perceived stigma and illness intrusiveness. Can J Psychiatr. 1994;39:608–16.

Muzzin LJ, Anderson NJ, Figueredo AT, Gudelis SO. The experience of cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1201–8.

Gudbergsson SB, Fossa SD, Dahl AA. Is cancer survivorship associated with reduced work engagement? A NOCWO study. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:159–68.

Richardson LC, Wingo PA, Zack MM, Zahran HS, King JB. Health-related quality of life in cancer survivors between ages 20 and 64 years: population-based estimates from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Cancer. 2008;112:1380–9.

Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Johnston M, Banks P. Intrusiveness of illness and quality of life in young women with breast cancer. Psycho Oncol. 1998;7:89–100.

Schimmer AD, Elliott ME, Abbey SE, Raiz L, Keating A, Beanlands HJ, et al. Illness intrusiveness among survivors of autologous blood and marrow transplantation. Cancer. 2001;92:3147–54.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Morey MC, Pieper CF, Sloane R, Snyder DC, et al. Lifestyle intervention development study to improve physical function in older adults with cancer: outcomes from Project LEAD. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3465–73.

Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M, Kasimis BS. Symptom and quality of life survey of medical oncology patients at a veterans affairs medical center—a role for symptom assessment. Cancer. 2000;88:1175–83.

Devins GM, Bezjak A, Mah K, Loblaw DA, Gotowiec AP. Context moderates illness-induced lifestyle disruptions across life domains: a test of the illness intrusiveness theoretical framework in six common cancers. Psycho Oncol. 2006;15:221–33.

Incrocci L. Radiotherapy for prostate cancer and sexual functioning. Hosp Med. 2004;65:605–8.

Lintz K, Moynihan C, Steginga S, Norman A, Eeles R, Huddart R, et al. Prostate cancer patients’ support and psychological care needs: survey from a non-surgical oncology clinic. Psycho Oncol. 2003;12:769–983.

Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, Neese L, Klein EA, Zippe C, et al. Seeking help for erectile dysfunction after treatment for prostate cancer. Arch Sex Behav. 2004;33:443–54.

Birgisson H, Pahlman L, Gunnarsson U, Glimelius B. Late adverse effects of radiation therapy for rectal cancer—a systematic overview. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:504–16.

Moriya Y. Function preservation in rectal cancer surgery. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006;11:339–43.

Karabulut N, Erci B. Sexual desire and satisfaction in sexual life affecting factors in breast cancer survivors after mastectomy. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27:332–43.

Melisko ME, Goldman M, Rugo HS. Amelioration of sexual adverse effects in the early breast cancer patient. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:247–55.

Henson HK. Breast cancer and sexuality. Sex Disabil. 2002;20:261–75.

Kornblith AB, Ligibel J. Psychosocial and sexual functioning of survivors of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:799–813.

Petronis VM, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weiss S. Investment in body image and psychosocial well-being among women treated for early stage breast cancer: partial replication and extension. Psychol Health. 2003;18:1–13.

Conger RD, Lorenz FO, Elder GHJ, Simons RL, Ge X. Husband and wife differences in response to undesirable life events. J Health Soc Behav. 1993;34:71–88.

Kornstein SG, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME, Yonkers KA, McCullough JP, Keitner GI, et al. Gender differences in chronic major and double depression. J Affect Disord. 2000;60:1–11.

Devins GM, Dion R, Pelletier LG, Shapiro CM, Abbey SE, Raiz L, et al. The structure of lifestyle disruptions in chronic disease: a confirmatory factor analysis of the illness intrusiveness ratings scale. Med Care. 2001;39:1097–104.

Loblaw DA, Bezjak A, Singh M, Gotowiec AP, Joubert D, Mah K, et al. Psychometric refinement of an outpatient, visit-specific satisfaction with doctor questionnaire. Psycho Oncol. 2004;13:223–34.

Devins GM, Styra R, O’Connor P, Gray T, Seland TP, Klein GM, et al. Psychosocial impact of illness intrusiveness moderated by age in multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health Med. 1996;1:179–91.

Devins GM, Edworthy SM, Lupus State Models Research Group ARAMIS. Illness intrusiveness explains race-related quality-of-life differences among women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2000;9:534–41.

Devins GM, Beanlands H, Mandin H, Paul LC. Psychosocial impact of illness intrusiveness moderated by self-concept and age in end-stage renal disease. Health Psychol. 1997;16:529–38.

Devins GM. Using the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale to understand health-related quality of life in chronic disease. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:591–602.

Mah K, Bezjak A, Loblaw DA, Gotowiec A, Devins GM. Measurement invariance of the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale’s 3-factor structure in men and women with cancer. Rehabil Psychol. 2010; accepted for publication.

Nunnally JC. Psychometric theory. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978.

Syse A, Tretli S, Kravdal Ø. Cancer’s impact on employment and earnings—a population-based study from Norway. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:149–58.

Platou TF, Skjeldestad FE, Rannestad T. Socioeconomic conditions among long-term gynaecological cancer survivors—a population-based case-control study. Psycho Oncol. 2010;19:306–12.

Hodgson NA, Given CW. Determinants of functional recovery in older adults surgically treated for cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27:10–6.

Clark JA, Bokhour BG, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Measuring patients’ perceptions of the outcomes of treatment for early prostate cancer. Med Care. 2003;41:923–36.

Monga U. Sexual functioning in cancer patients. Sex Disabil. 2002;20:277–95.

Tan G, Waldman K, Bostick R. Psychosocial issues, sexuality, and cancer. Sex Disabil. 2002;20:297–318.

Schwartz S, Plawecki HM. Consequences of chemotherapy on the sexuality of patients with lung cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6:212–6.

Shell JA, Carolan M, Zhang Y, Meneses KD. The longitudinal effects of cancer treatment on sexuality in individuals with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:73–9.

Banthia R, Malcarne VL, Varni JW, Ko CM, Sadler GR, Greenbergs HL. The effects of dyadic strength and coping styles on psychological distress in couples faced with prostate cancer. J Behav Med. 2003;26:31–52.

Ben-Zur H, Gilbar O, Lev S. Coping with breast cancer: patient, spouse, and dyad models. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:32–9.

Jenkins R, Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke C, Neese L, Klein EA, et al. Sexuality and health-related quality of life after prostate cancer in African-American and white men treated for localized disease. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30:79–93.

Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Desmond KA. Impact of different adjuvant therapy strategies on quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1998;152:396–411.

Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, Meyerowitz BE, Wyatt GE. Life after breast cancer: understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:501–14.

Breukink SO, Wouda JC, van der Werf-Eldering M, van de Wiel HBM, Bouma EMC, Pierie JP, et al. Psychophysiological assessment of sexual function in women after radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a pilot study on four patients. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1045–53.

van der Horst-Schrivers A, van Ieperen E, Wymenga ANM, Boezen HM, Weijmar-Schultz WCM, Kema IP, et al. Sexual function in patients with metatastic midgut carcinoid tumours. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;89:231–6.

Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. The volunteer subject. New York: Wiley; 1975.

Lavery JF, Clarke VA. Prostate cancer: patients’ and spouses’ coping and marital adjustment. Psychol Health Med. 1999;4:289–302.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funding from the University Health Network (UHN) Quality Program, the Princess Margaret Hospital’s Department of Radiation Oncology, and the Princess Margaret Hospital’s Quality of Life Clinical Research Program. This research was also supported in part by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) through a post-doctoral fellowship to Kenneth Mah and a Senior Investigator Award to Gerald M. Devins. Thanks to Bev Devins and Wendy Maharaj for assistance in collecting the data. We extend our gratitude to the members of the UHN Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care Quality of Life Manuscript-Review Seminar for their invaluable feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mah, K., Bezjak, A., Loblaw, D.A. et al. Do ongoing lifestyle disruptions differ across cancer types after the conclusion of cancer treatment?. J Cancer Surviv 5, 18–26 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-010-0163-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-010-0163-5