Abstract

Introduction

Psychological adjustment following cancer occurrence remains a key issue among the survivors. This study aimed to investigate psychological distress in patients with breast cancer following completion of breast cancer treatments and to determine its associated factors.

Materials and methods

This was a prospective study of anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients. Anxiety and depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale at three points in time: baseline (pre-diagnosis), 3 months after initial treatment and 1 year after completion of treatment (in all 18 months follow-up). At baseline, the questionnaires were administered to all the suspected patients while both patients and the interviewer were blind to the final diagnosis. Socio-demographic and clinical data included age, education, marital status, disease stage and initial treatment. Repeated measure analysis was performed to compare anxiety and depression over the study period. Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine variables that predict anxiety and depression.

Results

Altogether 167 patients were diagnosed with breast cancer. The mean age of breast cancer patients was 47.2 (SD = 13.5) years, and the vast majority underwent mastectomy (82.6%). At 18 months follow-up, data for 99 patients were available. The results showed that anxiety and depression improved over the time (P < 0.001) although at 18-month follow-up, 38.4% and 22.2% of the patients presented with severe anxiety and depression, respectively. ‘Fatigue’ was found to be a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression at 3 months follow-up [odds ratio (OR) = 1.04, 95% Confidence interval (CI) = 1.01–1.07 and OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 1.02–1.07 respectively]. At 18 months follow-up, anxiety was predicted by ‘pain’ (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.00–1.05), whereas depression was predicted by both ‘fatigue’ (OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.02–1.09) and ‘pain’ (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.01–1.08).

Conclusion

Although the findings indicated that the levels of anxiety and depression decreased over time, a significant number of women had elevated anxiety and depression at the 18 months follow-up. This suggests that all women should be routinely screened for psychological distress and that quality cancer care include processes to treat that 30% of women who have elevated psychological distress. In addition, if breast cancer patients indicated that they are suffering from fatigue or pain, these women who are at particular risk should be especially screened.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most important cancer among women worldwide. Global statistics show that the annual incidence of the disease is increasing, and this is occurring more rapidly in countries with a low incidence rate of breast cancer [1, 2]. In Iran, the incidence of the disease is raising, patients present with advanced stage of disease and they are relatively younger (about 10 years) than their western counterparts [3, 4].

Studies have shown that the prevalence of psychological distress among breast cancer patients is high, and they are at higher risk of developing severe anxiety, depression and potential mood disorders [5–7]. One study on a large sample of cancer patients reported that the prevalence of depression among breast cancer survivors was about 32.8% [8]. In addition, it has been reported that 40% of the patients with recurrent disease would suffer from anxiety and depression [9]. Despite the high prevalence of psychological morbidity and major depressive symptoms in breast cancer survivors, these go mostly misdiagnosed or undertreated in health care services. This gap leads to diminished quality of life, affects compliance with medical therapies and might reduce survival [10].

The occurrence of serious psychological distress among patients who suffer from breast cancer is due to several factors. The most responsible causes are treatment-related distress, worries regarding fear of death and disease recurrence, and altered body image, sexuality and attractiveness [11–13]. A recent publication reported that the expression of depression by patients with primary breast cancer could be even influenced by the progesterone receptor (PR) status of tumours [14].

There is extensive body of the literature that fatigue is among the most common symptoms in breast cancer survivors [15]. The prevalence of fatigue in breast cancer patients varies among studies ranging from 41% to 66% [16–18]. A study from Iran also reported that 49% of breast cancer patients experienced breast cancer-related fatigue [18]. In addition, it has been shown that there are strong associations between fatigue and psychological distress [19]. Pain also is common in breast cancer patients, and, in fact, it is considered as a disturbing symptom in cancer experience that impairs health-related quality of life [20, 21].

This study aimed to investigate the impact of breast cancer diagnosis and its treatment on psychological distress (anxiety and depression) of patients with breast cancer over time. It was assumed that the level of psychological distress would be higher around the time of diagnosis and during treatment than at the end of the treatment course. Thus, we were interested: (1) to identify the intensity of psychological distress before a final diagnosis of breast cancer was made (since it was thought that measuring psychological distress before the final diagnosis was achieved would provide an appropriate basis for the investigation of psychological distress over time), (2) to determine how psychological distress is affected after diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer, (3) to indicate changes of psychological distress 1 year after the completion of treatment and (4) to identify the impact of ‘fatigue and pain’ on developing psychological distress (since the relationship between psychological distress, pain and fatigue are overlooked).

Methods

Design

This was a prospective study of anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients. The study was conducted in Imam Khomeini hospital during a one complete calendar year. Imam Khomeini hospital is the biggest teaching hospital in Tehran, affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and is a referral centre for most cancer patients from Tehran and other provinces. Medical consultants identified newly suspected breast cancer patients from May 2002 to May 2003. All the patients were interviewed at this baseline stage, while both patients and the interviewer were blind to the final diagnosis. It was assumed that being blind to the final diagnosis would provide more precise information on anxiety and depression data. There were no restrictions on patient selection with regard to histology of breast cancer, disease stage and demographic characteristics. Altogether there were 332 newly suspected breast cancer patients. Sixteen cases refused to be interviewed (5%), while the remaining 316 (95%) women agreed to participate in the study. Women with confirmed histological diagnosis of breast cancer were further followed-up. First follow-up was scheduled 3 months after initial treatment, and the second assessment was made 1 year following the completion of the treatment course (18 months after pre-diagnosis stage). The study ended on December 2004. Patients with progression and the end-stage cases were not followed-up. Socio-demographic data included age, education and marital status. Clinical data consisting of disease stage and initial management were extracted from case records. The Iranian Center for Breast Cancer approved the study, and all the interviews were carried out with patients’ oral consent.

Measures

Psychological distress was measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The HADS is a brief instrument for measuring psychological distress in cancer patients. It consists of 14 items and contains two subscales: anxiety and depression. Each item is rated on a four-point scale, giving maximum scores of 21 for both the subscales. Scores of 11 up to 21 on each subscale are considered to be a significant case of psychological morbidity, while scores of 8–10 represents ‘borderline’ and 0–7 normal [22]. The psychometric properties of the Iranian version of HADS are well documented [23].

‘Fatigue’ and pain’ were measured using the fatigue and pain subscales derived from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30). ‘Fatigue’ consists of three items and ‘pain’ consists of two items. Higher score is indicating higher degree of symptom. The psychometric properties of the Iranian version of EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire are confirmed [24].

Analysis

Data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS).15 and restricted to the patients that their psychological distress data were available at follow-ups. Variation of anxiety and depression scores over the time was assessed using repeated measures analysis.

The logistic binary regression analysis was performed to investigate the predictive effects of demographic, clinical and symptom variables on developing anxiety and depression at 3 and 18 months follow-up. Using partial correlation analysis, the correlation of all the included predictors was assessed. The results were satisfactory, and positive associations were observed in the expected direction. ‘Anxiety and depression’ were considered as dependent variables and categorised into two groups: ≤7 (normal) and ≥8 (borderline and possible cases). Age, fatigue and pain were entered into the model as continuous data, and other variables were entered into the model as categorical data.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

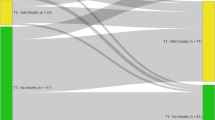

Of the cases studied, 167 had a confirmed diagnosis of breast cancer, while the remaining 149 patients were identified as having benign breast diseases. Patients with breast cancer were further followed-up. The mean age of breast cancer patients was 47.2 (SD = 13.5) years; most were married (69.4%) and have had primary or secondary education (66.5%). According to the case records, the vast majority of the cases (82.6%) underwent mastectomy and the disease stage was as follows: 17.4% local, 45.5% loco-regional and 37.1% metastasis. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample at three points in time are shown in Table 1. At the first follow-up, 150 breast cancer patients were re-interviewed, and the remaining 17 patients were excluded from the study. Of these 17 patients, six patients were refused to be re-interviewed, one was terminally ill, eight were lost and two were dead.

At the second follow-up, 99 patients were interviewed, and the remaining 51 patients were excluded from the study. Reasons for attrition were dislike (n = 25), loss to follow (n = 10) and death (n = 16). There were significant differences in age and educational levels between those who completed the study and those dropped from the study, indicating that older patients with lower educational level were more likely not to take part in follow-up assessments. Moreover, no significant differences were observed in anxiety and depression scores between those who stayed in the study and those who dropped out.

Anxiety and depression scores

Table 2 shows the anxiety and depression scores of breast cancer patients at three time points. Anxiety improved over time and showed a significant difference (P < 0.001), while there were little variations in the level of anxiety at pre-diagnosis and at 3 months assessments (mean scores 10.2 and 10.0, respectively); patients rated lower at 18 months follow-up (mean score 8.8). Also, a significant decline for depression score was detected at 18-month follow-up (P < 0.001).

The results indicated that 38.4% and 22.2% of the patients experienced severe anxiety and depression at 18 months assessment, respectively.

Correlation between fatigue, pain and psychological distress

The correlation between outcome variables (anxiety and depression), fatigue and pain was examined while controlling for age, education, marital status and the disease stage. The results are shown in Table 3. As expected, there were strong correlations between fatigue, pain, anxiety and depression. However, pain did not show significant correlation with anxiety and depression at 3 months follow-up, whereas the results at 18 months follow-up were highly significant.

Predictors of anxiety and depression at 3 months assessment

The results of regression analysis showed that at 3 months assessment, sever anxiety was predicted by ‘fatigue’ (Table 4). By rising one point on the ‘fatigue’ scale, the risk of developing anxiety increased by 4% (OR = 1.04, P = 0.001). Although patients with loco-regional and metastasis stages were at higher risk of developing sever anxiety, there were no significant relationship between anxiety and disease stage [OR (loco-regional) = 1.13, P = 0.86; OR (metastasis) = 1.33, P = 0.72].

It was found that significant risk factor for developing depression was ‘fatigue’ (OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 1.02–1.07). Widowed experienced higher risk of developing depression (OR = 1.83) although no significant relationship was observed between depression and marital status.

Predictors of anxiety and depression at 18 months assessment

The results of regression analysis of anxiety and depression at 18 months follow-up are shown in Table 5. Pain was found to be the most significant variable for developing anxiety at 18 months assessment (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.00–1.05). Although not significant, widowed showed higher risk of developing anxiety (OR = 1.20).

Risk factors of depression at 18 months follow-up were ‘fatigue’ (OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.02–1.09) and ‘pain’ (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.01–1.08). In addition, the results showed that being single could be a protective factor for developing severe depression (OR = 0.02, 95% CI = 0.00–0.78).

Discussion

This study provided data on psychological distress among a consecutive sample of 99 breast cancer patients during an 18-month follow-up using a validated measure of anxiety and depression. As compared to pre-diagnosis and 3 months assessments, patients had lower scores on both psychological disorders 1 year after the completion of their treatment (Table 2). Similarly, a study from the U.S. indicated that patients with breast cancer had lower scores of anxiety and depression at 3 months post-treatment [25]. Evidence suggests that psychological distress in breast cancer patients is more common throughout the course of the disease and also in the recurrent phase of breast cancer [10, 26]. Therefore, to prevent clinical psychological distress, there is a need to recognize the problem throughout the course of the disease and its treatment and if accrued manage disorders appropriately.

However, the findings indicated that 38.4% of the patients experienced severe anxiety and 22.2% had severe depression (Table 2). Similarly, studies have shown that women with breast cancer are highly exposed to developing anxiety and depression even after the completion of their treatment. A study of breast cancer survivors from Germany with an average of 47 months follow-up demonstrated that 38% of the patients had moderate to high anxiety and 22% had moderate to high depression as measured with the HADS [5]. A study among 300 Thai breast cancer patients indicated that the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms were 19% and 16.7%, respectively [27]. A review of the literature on depression, quality of life and breast cancer pointed out that breast cancer survivors report a higher prevalence of mild to moderate depression with a lower quality of life in all the areas except for family functioning. Since co-morbid depression significantly increases the burden of distress and dysfunction for patients with breast cancer, treatment of depression was recommended highly [28].

The results of regression analysis showed that ‘fatigue’ would be a significant risk factor for developing anxiety and depression at 3 months follow-up (Table 4). At 18 months follow-up, developing anxiety was significantly predicted by ‘pain’, whilst major determinants of developing depression were found to be ‘fatigue and pain’ (Table 5). It has been demonstrated that side effects of chemotherapy or radiotherapy in breast cancer patients such as nausea, fatigue and pain are often associated with depressive symptoms and may impair the quality of life [29, 30]. In general, severe fatigue is a problematic issue in breast cancer survivors, which is related to physical, psychological, social and cognitive factors [31]. Low psychological distress along with low level of fatigue in patients with breast cancer may cause a greater cancer resistance [32]. Furthermore, the study findings indicated that pain predicted higher levels of both anxiety and depression at 18 months follow-up (Table 5). One explanation for such findings could be the fact that fears of disease progression and the reality of living with breast cancer are greatly associated to perceived amount of impairments and physical and mental quality of life [33]. A survey on patients with advanced cancer showed that the ‘pain interference’ and to a lesser extent, ‘pain severity’ have been significantly correlated with developing anxiety among patients [34]. Nevertheless, similar findings showed that ‘pain and fatigue’ were significant predictors of anxiety and depression among breast cancer patients [27].

Although it was found that lower educational levels would be protective for developing psychological distress at 3 months follow-up, there were no significant statistical relationships between education and psychological disorders (Table 4). At 18 months follow-up women with primary education showed a higher risk for developing anxiety, whereas ‘being illiterate’ increased the risk of developing depression. However, no significant associations were observed (Table 5). Similarly, lower educational level has been found to be a predictor of psychological co-morbidity in patients with breast cancer [5]. This somehow might be explained by the fact that patients with higher educational levels have a greater opportunity to be aware about their disease and its related aspects.

‘Being single’ was found to be a protective factor for developing psychological distress at both assessments while widowed showed a greater risk. However, there were no significant relationships between marital status and risk of severe psychological distress except for non-married patients at 18 months follow-up, where they showed a significant decreased risk of depression (Tables 4, 5). This might be explained by the fact that single and widowed patients have had minor worries regarding their family and social responsibilities. On the contrary, it has been shown that social ties are a factor that is inversely related to risks of breast cancer mortality and all-cause mortality and that independently predicts health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer [35, 36]. Even studies have reported that being unaccompanied by spouse for hospital follow-ups could increase anxiety and depression among breast cancer patients [37]. Alternatively, married women with a breast cancer diagnosis may be more exposed to marital duties or marital breakdown. A literature review on the topic is suggesting that the majority of the marital relationships remain stable after breast cancer, and that breakdown is most likely in those relationships with pre-existing difficulties [38].

In addition, it was found that disease progress predicted higher risk of developing both psychological distress at 3 months assessment and depression at 18 months assessment. However, no significant associations were found. It is known that disease progress is a determinant factor of psychological co-morbidity among breast cancer patients [5].

This study was limited due to its small cohort of breast cancer patients. Nearly one-third of the patients were dropped out during the follow-up assessments. Moreover, no specific fatigue and pain measures were used in the study. In general, the findings showed that the impact of breast cancer diagnosis and its treatments are important and. in particular, improved diagnosis and treatment for breast cancer might provide a better emotional environment and enhance coping skills among breast cancer survivors.

Conclusion

Although the findings indicated that the levels of anxiety and depression were decreased over time, a significant number of women had elevated anxiety and depression at the 18 months follow-up. This suggests that all women should be routinely screened for psychological distress and that quality cancer care include processes to treat that 30% of women who have elevated psychological distress. In addition, if breast cancer patients indicated that they are suffering from fatigue or pain, then these women who are at particular risk should be especially screened.

References

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2005) Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55:74–108

Wilson CM, Tobin S, Young RC (2004) The exploding worldwide cancer burden: the impact of cancer on women. Int J Gynecol Cancer 14:1–11

Harirchi I, Ebrahimi M, Zamani N, Jarvandi S, Montazeri A (2000) Breast cancer in Iran: a review of 903 case records. Public Health 114:143–145

Mousavi SM, Montazeri A, Mohagheghi MA, Mousavi Jarrahi A, Harirchi I, Najafi M, Ebrahimi M (2007) Breast cancer in Iran: an epidemiological review. Breast J 13:383–391

Mehnert A, Koch U (2008) Psychological co-morbidity and health-related quality of life and its association with awareness, utilization and need for psychosocial support in a cancer register-based sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res 64:383–391

Deshields D, Tibbs T, Fan MY, Taylor M (2006) Differences in patterns of depression after treatment for breast cancer. Psychooncology 15:398–406

Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A (2005) Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. BMJ 330:402–705

Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S (2001) The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology 10:19–28

Okamura H, Watanabe T, Narabayashi M, Katsumata N, Ando M, Adachi I, Akechi T, Uchitomi Y (2000) Psychological distress following first recurrence of disease in patients with breast cancer: prevalence and risk factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 61:131–137

Somerset W, Stout SC, Miller AH, Musselman D (2004) Breast cancer and depression. Oncology (Williston Park) 18:1021–1034

Ganz PA (2008) Psychological and social aspects of breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Oark) 22:642–646

Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, Gremore TM, Keefe FJ (2006) Psychological issues confronting young women with breast cancer. Breast Dis 23:103–113

Helms RL, O’Hea EL, Corso M (2008) Body image issues in women with breast cancer. Psychol Health Med 13:313–325

Snoj Z, Akelj MP, Lieina M, Pregelj P (in press) Psychosocial correlates of progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Depress Anxiety (2008 Nov 21. Epub ahead of print)

Minton O, Stone P (2008) How common is fatigue in disease-free breast cancer survivors? A systematic review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat 112:5–13

Meeske K, Smith AW, Alfano CM, McGregor BA, McTiernan A, Baumgartner KB, Maone KE, Reeve BB, Ballard-Barbash R, Bernstein L (2007) Fatigue in breast cancer survivors two to five years post diagnosis: a HEAL study report. Qual Life Res 16:947–960

Kim SH, Son BH, Hwang SY, Han W, Yang JH, Lee S, Yun YH (2008) Fatigue and depression in disease-free breast cancer survivors: prevalence, correlates and association with quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 35:644–655

Haghighat SH, Akbari ME, Holakouei K, Montazeri A (2003) Factors predicting fatigue in breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 11:533–538

Bennett B, Goldstein D, Lioyd A, Davenport T, Hichie I (2004) Fatigue and psychological distress-exploring the relationship in women treated for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 40:1689–1695

Green CR, Montague L, Hart-Johnson TA (2009) Consistent and breakthrough pain in diverse advanced cancer patients: a longitudinal examination. J Pain Symptom Manage 37:831–847

Montazeri A (2008) Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 27:32

Zigmond AS, Snaith PR (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiat Scand 67:361–370

Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Ebrahimi M, Jarvandi S (2003) The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:14

Montazeri A, Harirchi I, Vahdani M, Khaleghi F, Jarvandi S, Ebrahimi M, Haji-Mahmoodi M (1999) The European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Support Care Cancer 7:400–406

Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Mattes ML, Trehan S, Robinson CB, Tewfik F, Roman SL (2007) Adjusting to life after treatment: distress and quality of life following treatment for breast cancer. Br J Cancer 97:1625–1631

Northouse LL, Mood D, Kershaw T, Schafenacker A, Mellon S, Walker J (2002) Quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family members. J Clin Oncol 20:4050–4064

Lueboonthavatchi P (2007) Prevalence and psychosocial factors of anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients. J Med Assoc Thai 90:2164–2174

Reich M, Lesur A, Perdrizet-Chevallier C (2008) Depression, quality of life and breast cancer: a review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat 110:9–17

Smith EM, Gomm SA, Dickens CM (2003) Assessing the independent contribution to quality of life from anxiety and depression in patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med 17:509–513

Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Love A, Clarke DM, Bloch S, Smith GC (2004) Psychiatric disorder in women with early stage and advanced breast cancer: a comparative analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 38:320–326

Servaes P, Verhagen S, Bleijenberg G (2002) Determinants of chronic fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Ann Oncol 13:589–598

Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Idler E, Bjorner JB, Fayers PM, Mouridsen HT (2007) Psychological distress and fatigue predicted recurrence and survival in primary breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 105:209–219

Mehnert A, Berg P, Henrich G, Herschbach P (in press) Fear of cancer progression and cancer-related intrusive cognition in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology (2009 Mar 6. Epub ahead of print)

Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Katsouda E, Galanos A, Vlahos L (2006) Psychological distress of patients with advanced cancer: influence and contribution of pain severity and pain interference. Cancer Nurs 29:400–405

Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Schernhammer ES, Holmes MD, Kawachi I (2006) Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 24:1105–1111

Filazoglu G, Griva K (2008) Coping and social support and health related quality of life in women with breast cancer in Turkey. Psychol Health Med 13:559–573

Karakoyun-Celik O, Gorken I, Sahin S, Orcin E, Alanyali H, Kinay M (2009) Depression and anxiety levels in women under follow-up for breast cancer: relationship to coping with cancer and quality of life. Med Oncol (in press)

Taylor-Brown J, Klipatrick M, Maunsell E, Dorval M (2000) Partner abandonment of women with breast cancer. Myth or reality? Cancer Pract 8:160–164

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vahdaninia, M., Omidvari, S. & Montazeri, A. What do predict anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients? A follow-up study. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 45, 355–361 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0068-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0068-7