Abstract

Though it has not been shown to deliver any biological importance, mercuric(II) ion (Hg2+) is a deleterious cation which poses grievous effects to the human body and/or the ecosystem, hence, the need for its sensitive and selective monitoring in both environmental and biological systems. Over the years, there has been a great deal of work in the use of fluorescent, colourimetric, and/or ratiometric probes for Hg2+ recognition. Essentially, the purpose of this review article is to give an overview of the advances made in the constructions of such probes based on the works reported in the period from 2011 to 2019. Discussion in this review work has been tailored to the kinds of fluorophore scaffolds used for the constructions of the probes reported. Selected examples of probes under each fluorophore subcategory were discussed with mentions of the typically determined parameters in an analytical sensing operation, including modulation in fluorescence intensity, optimal pH, detection limit, and association constant. The environmental and biological application ends of the probes were also touched where necessary. Important generalisations and conclusions were given at the end of the review. This review article highlights 196 references.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mercury (II) (Hg 2+ ) detection

Generating means to detect mercury(II) (Hg2+) is necessary since reports have shown Hg2+ to be a health threat to the world environment, this stemming from its highly toxic nature and ubiquitous impact in both the lithosphere and hydrosphere (Coronado et al. 2005). Years of experimental works have shown Hg2+ to pose health problems not only to human beings but also to other animal species. Hg2+ contamination is being engendered through natural and anthropogenic endeavours, including ocean and volcanic eruptions, mining of metal (especially artisanal and small-scale gold mining, ASGM), incineration of waste, tanning of leather, electroplating, occupational operations, dental care, preventive medical practices, agricultural and industrial operations, and fossil fuel combustion (from coal-burning power plants) (Renzoni et al. 1998; Rice et al. 2014; Bravo et al. 2014; Costa et al. 2016; Martinez-Finley et al. 2014). Elemental mercury and ionic mercury (Hg and Hg2+, respectively) have the tendency to be transformed by microorganisms like bacteria into methylmercury (MeHg), which is a potentially harmful neurotoxin capable of bioaccumulation into the food chain (Nolan and Lippard 2008). Its damaging effect on the placenta of pregnant women has been particularly identified, which thereby poses a developmental problem to foetal brain and central nervous system, resulting in a developmental delay in children (Coronado et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2008; Gibb and OLeary 2014). This can then implicate certain biological processes, inducing a chain of diseases including splanchnic damage, nosebleed, headache, perforation of the stomach, nerve disorder, intestines septum, and acute renal failure (Renzoni et al. 1998; Zhai et al. 2012; Hoyle et al. 2005; Zarlaida 2017). As such, exposure to low concentrations of Hg2+ can trigger numerous grievously damaging effects to the human heart, kidney, stomach, and intestines, resulting in metabolic disorders, motor and cognitive disorders, and sensory malfunctions and disorders (Rice et al. 2014; Hoyle and Handy 2005; Arya and Bhansali 2011; Ghasemi et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2008). This has resulted in stringent regulations imposed on relevant industries to bring about a clean-up system for mercury-laden wastewater before its discharge into waste streams. The maximum permissible limit of total mercury in wastewater discharge is 10 µg/L (US Environmental Protection Agency 2001; Kumar et al. 2012a). US EPA’s previously regularised guideline of Hg2+ in drinking water of 1 µg/L was changed to 6 µg/L in 2005—the former value being based on methylmercury (MeHg), whilst the recent guideline is based on inorganic mercury (Frisbie et al. 2015). Amongst the various heavy metals, Hg2+ ion shows the most toxicity, hence, the inspiration and need for its monitoring. These obvious environmental and biological threats which (Hg2+) poses have engendered the construction of methods for its detection and measurement in aqueous phases—three of such widely exploited concepts being the fluorescent, colourimetric, and/or ratiometric detection modes due to their pre-eminence over other detection techniques.

The fluorescence, colourimetric, and ratiometric optical detection methods

The past twenty plus years of the arrival of the supramolecular chemistry have recorded stunning successes in the constructions of fluorescent, colourimetric, and ratiometric probes as vibrant, vital tools for the sensing of environmentally and biologically relevant cations and anions, and also for the detection of H+ (proton) in biological assays (Gunnlaugsson et al. 2006; Lodeiro and Pina 2009; Duke et al. 2010; Georgiev et al. 2011; Park et al. 2020). Compared to conventional analytical detection methods of voltammetry, polarography, X-ray fluorescence analysis, infrared spectroscopy, atomic fluorescence spectrometry, high-performance liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry, atomic absorption spectroscopy, etc., which have been utilised to recognise heavy metal ions like Hg2+, the fluorescence method is a preferred, sought-after, and powerful analytical tool. The fluorescence technique has been employed for molecular recognition since it offers the benefits of high spatial resolution, ultra-high sensitivity and selectivity, real-time detection, local observation, operational simplicity, equipment’s inexpensiveness, quick response time, and non-destructive nature (Lee et al. 2015; Carter et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2012, 2011; Chen et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2013; Singha et al. 2019). Because of these merits, there have been successful instances of the application of the fluorescent technique in clinical diagnostics, biotechnology, biochemistry and molecular biology, materials and environmental sciences (Mason 1999). It has been used for the monitoring of diverse groups of analytes including heavy metal ions, explosives, peptides, and pesticides (Bigdeli et al. 2019).

The colourimetric method, a powerful analytical technique like the fluorescence method, has also been harnessed in the field of sensing science as it affords the ability for naked-eye monitoring of analytes even before spectrophotometric analytical investigation (Kaur et al. 2018). Colourimetric probes upon interaction with analytes give ‘naked-eye’ (i.e. visibly detectable) colour changes, which are easily detectable signal outputs that do not need any sophisticated instruments. Diagnostic assays like blood-glucose monitoring and early pregnancy tests are two key instances where the colourimetric method has been successfully applied (Bicker et al. 2011).

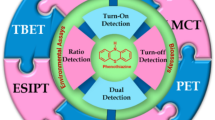

The ratiometric detection approach has been put in place to overcome some sensitivity difficulties usually encountered in optical detection (e.g. interference from a variety of analyte-independent factors, including instrumental parameters, the probe’s microenvironment, the probe’s local concentration, and photobleaching) (Bigdeli et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2015). Ratiometric fluorescence detection method affords the possibility of simultaneous recording of two measurable signals in the presence and absence of analyte (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985). This detection technique is usually both desirable and preferable as it can measure fluorescence signals at two different wavelengths unlike the traditional methods that measure fluorescence intensity only at a single wavelength. Fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) allows for the possibility of precise and quantitative read-outs. Due to this desirable property of FRET, many ratiometric fluorescent probes, such as some discussed in this review, have been designed by adopting the FRET-based ratiometric approach. FRET, in principle, is a distance-dependent physical process involving the non-radiative transfer of energy from an excited molecular fluorophore, i.e. the donor, to another fluorophore, i.e. the acceptor, through an intermolecular long-range, dipole–dipole coupling. FRET can measure molecular closeness at angstrom distances of 10–100 Å and is highly efficient if the donor and acceptor are positioned within the Förster radius (i.e. the distance at which half the excitation energy of the donor is transferred to the acceptor, usually 3–6 nm). FRET is a sensitive technique that could investigate biological processes which induce changes in molecular proximity as it is dependent on the one-sixth of inter-molecular separation (Förster 965; Clegg 1996; Lakowicz 1999; dos Remedios et al. 1987). Apart from FRET, in the context of this review work, other detection mechanisms/strategies including photoinduced electron transfer (PET), internal charge transfer (ICT), twisted intramolecular charge transfer (TICT), electron transfer (ET), energy transfer (eT), through-bond energy transfer (TBET), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), time-gated fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TG-FRET), aggregation-induced emission (AIE), through-bond fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TBFRET), etc., have also been employed for the design of some reported probes towards Hg2+detection.

Overview of commonly used molecular motifs for sensing operation

Prompted by the efficacy of the fluorescence, colourimetric, and ratiometric detection techniques, a plethoric number of probes have been developed using various categories of fluorophore motifs. The analytical advantages of small-molecule probes have been recognised, viz high selectivity, bioorthogonality, minimal perturbation to living systems, high sensitivity, simplicity of manipulation, and non-sophistication of instrumentation (Chan et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2011). The year 1845 saw the report of the first fluorescent organic molecule, the sulphate of quinine, which was discovered by Sir John Herschel (1845), whilst the year 1852 saw the advent of the term ‘fluorescence’, which was conceptualised by Stokes (1845). The discovery of quinine sulphate (Fig. 1) has informed the discovery of many other organic compounds which fluoresce with distinctive colours. These include fluorescein and rhodamine derivatives, boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) dyes, cyanine dyes, and others (Fig. 1) (Zheng et al. 2013; Baeyer 1871; Ceresole 1888; Loudet and Burgess 2007; Luo et al. 2011). Dyes which fluoresce with red to near-infrared (NIR) light show great potentials for in vivo imaging in biological systems, owing to their ability to penetrate tissues in the red to near-infrared wavelength region (650–900 nm) (Luo et al. 2011; Weissleder and Ntziachristos 2003). This has implied the development of a new class of dyes, which not only emit red or NIR fluorescence but possess higher extinction coefficients. This class of dyes anchors fluorophores functionalised with additional ring systems or heteroatoms or dye moieties which have been structurally modified. (Umezawa et al. 2008; Yuan et al. 2012; Egawa et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2011; Samanta et al. 2010). Lately, fluorescent dyes with two-photon imaging and super-resolution imaging abilities (Kim and Cho 2009; Krishna et al. 2006; Maçôas et al. 2011) have been gaining momentum for sensing purposes.

Probes based on supramolecular structures usually show superior sensing properties to those based on simple synthetic organic dyes. Common supramolecular structures which are successful in the designs and syntheses of Hg2+ probes include 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecanes (cyclen), cyclodextrin, calixarene, porphyrin, crown ethers, helicene, peptidyl, amongst others (Fig. 2) (Kappe 1994; Liu et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2018; Li et al. 2018; Shen and Chen 2012; Tung 2004; Athey and Kiefer 2002; Rothemund 1936; Gierczyk et al. 2013). Many synthetic organic probes have been simply employed in their polymeric forms for improved sensing properties. Polymer-embedded optical probes stand out for their several merits, including, signal amplification, ease of use, simplicity of fabrication into devices, and combination of different outputs (Kim et al. 2011).

A burgeoning interest exists in the development of probes based on metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent-organic frameworks (COFs) as they possess outstanding features of large surface areas, regular pore structures, tunability in their pore sizes and functionalities, and thermal stabilities (Zhang and Yuan 2018; Rudd et al. 2016). These strong merits make them employable as probes for imaging applications. Typically, MOFs have two components: the metal ion or cluster and the organic linker. Common organic linkers used for the constructions of MOFs have been summarised in a paper published by Allendorf’s group. The properties of MOFs can be modulated easily by varying the linker, metal, and/or growth conditions (Allendorf et al. 2009). Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are covalent porous crystalline polymers that enable the elaborate integration of organic building blocks into an ordered structure with atomic precision. COFs possess high thermal stabilities, low mass densities, and long-lasting porosity. These interesting properties of COFs have made them useful towards sensing ends. Both two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) COFs have been recognised (Feng et al. 2012). A diversity of building blocks is available for the development of COFs, and this has been given in a reported literature (James 2003).

Research investigations have found out that some drawbacks of fluorescent dyes can be combated or at the very least ameliorated by the enclosure of the dye in nanoparticle delivery systems (Koo et al. 2007). The distinctive optical and electronic properties of nanomaterials have informed their increasing use as probes and diagnostic agents (Xu et al. 2014). Probes based on nanomaterials possess the advantages of stronger fluorescent emission, large surface-area-to-volume ratio, stability, multifunctionality, target specificity, simplicity, novelty, high selectivity and sensitivity, excellent sensing parameters such as low detection limit and water solubility (Guo et al. 2014; Song et al. 2010). Common examples of nanomaterials include gold nanorods, silver nanoparticles, DNA oligomers, silica nanoparticles (Xu and Suslick 2010; Guo et al. 2009; Ritchie et al. 2007; Shang and Dong 2008; Zhou et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2015a), quantum dots (QDs) (e.g. CdSe and CdTe), TiO2 NPs, SiO2 NPs, and Fe3O4 NPs (Lin et al. 2011). Probes based on QDs show superior features of outstanding stability, tunable and minuscule emission spectrum, large quantum yield and Stokes’ shifts, wide excitation wavelength, which mirror the merits of synthetic organic probes. Graphene oxides (GOs) show tunable physicochemical properties and good dispersion ability in many solvents, especially in water (Freeman et al. 2009; Abdelhamid and Wu. 2015). Many mercuric (II) (Hg2+) nanoprobes either make use of the change in colour (absorption) or fluorescence intensity (‘turn on’ and ‘turn off’) in their detection modes. Some of these can be DNA-functionalised or non-DNA-functionalised.

The purpose, scope, and structure of this current review

To be as brief and direct as possible, the fundamental rules and principles governing the design strategies of probes are left out in this review paper. Insights into these have been given in some other excellent review works (Chan et al. 2012; Kaur et al. 2016). Even though as of the present, a large assembly of fluorescent, colourimetric, and/or ratiometric probes for Hg2+-selective monitoring with suitable applications have been covered in a few previously reported works; however, such exist in rather ‘old’ references. (Readers are referred to see the review articles by Nolan and Lippard (2008), Mahato et al. (2014), and Chen et al. (2015.) This current review has the purpose of presenting a detailed account of the recent progress made in the designs and syntheses of ‘new’ optical probes for Hg2+ detection from 2011 to 2019.

This article is structured in such a way that the body of the review work is based on four broad categories of selected fluorophore scaffolds used for the structural designs of the probes reported (Fig. 3): 1. simple molecular ligands/synthetic organic dyes; 2. supramolecules: carbohydrates and polymers; 3. metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs); and 4. nanoprobes: nanoparticles, quantum dots (QDs), and graphene oxides (GOs) (Fig. 3). The sensing properties of the probes under each subsection have been discussed by emphasising the parameters of the most suitable solvent system, optimum pH value/range, interference property, detection limit, and association constant. Some occasional mentions of the probes’ utility in imaging Hg2+ in biological systems are also given. Sufficient references, totalling 196 articles, are reviewed in strength to keep abreast of the works done in various labs whilst ensuring succinctness of the report. All reported compounds either employ the fluorescence, colourimetric, and/or ratiometric method in their detection modes (Fig. 3). In some instances, however, the mentioned compounds make use of combined fluorescence or colourimetric or ratiometric methods in their sensing technique/detection methodology. This review closes by giving a brief conclusion that will help guide future research works in the chemistry of Hg2+ sensing.

Hg2+-selective small-molecule probes based on different fluorophore motifs

Based on different subfluorophores, an account of small-molecule probes for the monitoring of mercuric (II) ion (Hg2+) is detailed below.

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on simple molecular ligands/synthetic organic dyes

A large percentage of probes that exist to date are based on conventional simple molecular ligands/synthetic dyes constructed from various organic fluorophores such as the 1,8-naphthalimide, rhodamine, coumarin, pentaquinone, boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY), cinnamaldehyde, Schiff base, anthracene, squaraine, pyrene, azo derivative, amongst many others. Small-molecule probes do not require invasive and often tedious genetic modification of the system and can be applied to many samples, and they, therefore, demonstrate potential clinical applications (Kim and Cho 2015).

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on naphthalimide fluorophore

The naphthalimide fluorophore possesses several desirable properties including a large Stokes’ shift and a high quantum yield that inform its choice as a common fluorophore for the development of probes (Aderinto et al. 2016; Aderinto and Imhanria 2018; Wang et al. 2017). Moreover, its chemistry is versatile, allowing the possibility for distinct functionalisation that confers tailored properties on the probes constructed from this moiety (Moro et al. 2010).

Chen’s group recently reported a naphthalimide-based fluorescent and colourimetric probe, NAP-PS, that houses the diphenylphosphinothioyl group for Hg2+ detection (Chen et al. 2019). In HEPES buffer (1.0 mM, pH = 7.4), amongst the many other ions (Zn2+, Cu2+, Mn2+, Pb2+, Al3+, Ca2+, Cr3+, K+, Fe3+, Fe2+, Cs+, Na+, Ni2+, Mg2+, Sr2+, Cd2+, and Ag+) investigated, only the addition of Hg2+ leads to a significant ratiometric response of the fluorescence intensities at 450 nm to 550 nm. The ratiometric fluorescence response of NAP-PS is due to its reaction with mercury, which cleaves the thiophosphinate P–O bond in the probe to form the intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) system, NAP-O. The linear range of detection was within 0–12 nM, whilst the detection limit was calculated as 43 nM. The probe was also capable of Hg2+ monitoring in the solid state. Using two-photon microscopy, the designated probe could bioimage Hg2+ in both HeLa live cells and tissues with very low cytotoxicity exhibited.

La’s research group reported the design of their newfound 4-Amino-1,8-naphthalimide-based fluorescent probe, Hg-1 (Fig. 4), for Hg2+ monitoring, which could also sense CN− and F− via the colourimetric method, thereby acting as a multianalyte probe (La et al. 2016). The design strategy was based on the combination of both PET and ICT, which allow for a dual analyte monitoring mode. (PET-based probe design involves the fluorophore unit connected to the ionophore unit through a spacer, whilst ICT-based probe design involves the direct connection of the fluorophore unit and ionophore unit to form a single species (Gupta and Kumar 2016.) The reported compound underwent a multiplication in its fluorescence signal intensity after Hg2+ was added, whilst the other ions tested together did not modulate the fluorescence signal intensity of the probe significantly. There was a linear response of the probe for Hg2+ monitoring with the detection limit reportedly low to the level of 2.40 × 10–7 M (lower than those of previously reported probes), and the association constant reportedly high as 4.12 × 105 M. The analysis of the Job’s plot and 1H NMR results gave the stoichiometric ratio to be 1:1 (Fig. 5).

Proton NMR of Probe Hg-1 in the absence and presence of excess Hg2+. Key finding: there was an upfield shift in the aromatic protons owing to increased electron density upon protonation (La et al. 2016)

Two naphthalimide-appended fluorescent probes, Hg-2 and Hg-3 (Fig. 4), were devised and reported by Li and his research group members (Li et al. 2016). In phosphate buffer, the two compounds display ultra-high-level sensitivities and selectivities for Hg2+ detection. It was observed that Hg-2 and Hg-3 could detect Hg2+ over a vast expanse of pH, between 7.0 and 10.0. In a 10 μM solution of Hg-2 in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.5), upon the addition of cations like Ag+, Al3+, Ba2+, Cd2+, Ca2+, Co2+, Cr3+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Li+, K+, Na+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Mn2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, and Hg2+, only Hg2+ led to ca. 90% suppression of the fluorescence intensity of Hg-2; meanwhile, the other cations impressed only benign effects on the fluorescence intensity. A similar observation went for Hg-3. There was linearity in Hg2+ monitoring by Hg-2 between the concentration range of 2 and 10 μM, and the lowest detection limits of Hg-2 and Hg-3 for Hg2+ detection were 2.1 μM and 3.1 μM, respectively. Analytically, Hg-2 exhibits higher selectivity and sensitivity towards Hg2+ than Hg-3, this being accrued to the fact that the conjugation action of morpholine which exists in Hg-3 makes it to poorly bind to Hg2+. The proton NMR of the binding of Hg-2 to Hg2+ shows the disappearance of a major peak downfield in the NMR spectrum upon the addition of Hg2+.

Work in mercury probes’ development has also shifted towards the employment of sulphur-based functional groups (like sulphoxides and thioureas) since they display great affinities for measured analytes in aqueous environments. Vonlanthen and his team members developed a PET thiourea–naphthalimide-based probe, Hg-4 (Fig. 6) that demonstrates Hg2+ sensing over competing metal ions like Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Ag+, Zn2+, Cd2+, Hg2+, and Pb2+ in CH3OH (Vonlanthen et al. 2014). At pH 5.5 or lower, in 9:1 H2O/CH3OH, no fluorescence enlargement was observed, but there was a massive amplification of the fluorescence in the case of Hg2+. Job’s plot establishes a 1:1 stoichiometry of the interaction between the probe and Hg2+ ion. Eventually, the compound was applied to image Hg2+ in living mammalian cells (Fig. 7), indicating its practical utility potential in biological system.

Scheme of fluorescent Probe Hg-4 exhibiting the PET mechanism (Vonlanthen et al. 2014)

Fluorescence images showing HeLa cells treated with Probe Hg-4 and HgCl2. a HeLa cells treated overnight with a DMSO control at 37 °C. b Cells treated overnight with a DMSO control followed by HgCl2 (200 μM) for 10 min at 37 °C. c Cells incubated overnight with Probe Hg-4 (20 μM) at 37 °C. d Cells treated overnight with Probe Hg-4 (20 μM) followed by HgCl2 (200 μM) for 10 min at 37 °C. Imaging was done on a Zeiss Axio Observer inverted microscope with objective = ×63; excitation wavelength = 365 nm, emission wavelength = 445/50 nm (Vonlanthen et al. 2014)

Un et al. introduced a novel, simple, and versatile fluorescent Probe Hg-5 (Fig. 8) based on the N-butyl-4-bromo-1,8-naphthalimide moiety. The probe was employed for a fluorescence ‘turn on’ monitoring of Hg2+ over a wide range of several other cations, including Zn2+, Mn2+, Ba2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Co2+, Pb2+, Mg2+, Cd2+, Fe2+, Al3+, Ag+, Na+, and Li+ (Un et al. 2014). In aqueous solution (THF-H2O, 1:1, pH = 7.4, 10 mM Tris–HCl), Hg2+ addition to a solution of Hg-5 induced a notable enhancement of fluorescence. The fluorescence detection occurred over the range 1–30 μM, with a detection limit of 6.28 × 10–8 M and an association constant of 5.4 × 104 M−1 calculated. The fluorescence imaging experiments of Hg-5 for Hg2+ tracking in living cells were successfully demonstrated.

Structure of Probe Hg-5 (Un et al. 2014)

Moon et al. employed a new thionaphthalimide-based probe, Hg-6, and its two monothio derivatives, Hg-7 and Hg-8 (Figs. 9, 10), for the sensitive and selective monitoring of Hg2+ through an ‘off–on’ mode (Moon et al. 2013). In 30% aqueous CH3CN, the fluorescence intensity of Probe Hg-6 at 537 nm was escalated upon the addition of 20 equivalents of Hg2+, whereas the effects of other tested cations on the fluorescence intensities of the probes were minuscule. The reported Probe Hg-6 could allow the detection of Hg2+ ion in an amount as low as 2.7 μM. The isomeric probes Hg-6 and Hg-7 were demonstrated to exhibit varied sensing behaviours with Hg-6 showing a faster signalling speed than Hg-7. This was explained as due to the carbon resonance of the more electron-rich thiocarbonyl group of Hg-6 which possesses more electron-rich sulphur and appears in a higher field (192.5 ppm) than that of Hg-7 which appears in a lower field (194.2 ppm) (Fig. 9). The signalling behaviour of the dithio-derivative, Hg-8, was not reported, only that upon interaction with Hg2+, it became desulphurised to the monothiol-derivative, Hg-7.

Partial 13C NMR spectra of Probes Hg-6 and Hg-7 in CDCl3 (Moon et al. 2013)

Structure of Probe Hg-8 (Moon et al. 2013)

Probe Hg-9 (Fig. 11) was used by Zhang et al. for the signalling detection of Hg2+ amongst several other cations, including Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Cr2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, Fe2+, Mn2+, Co2+, and Cd2+ (Zhang et al. 2013). In EtOH/H2O (1/2, v/v), the addition of Hg2+ to a solution of the probe led to a marked increase in the fluorescence intensity of Hg-9, whilst no obvious disturbance in detection was observed from other tested cations. The binding stoichiometry of Hg-9 towards Hg2+ as furnished by the Job’s plot analysis yielded the establishment of a 1:1 complex between Hg2+ and Hg-9. This was further evidenced by the results of the proton NMR.

Structure of Probe Hg-9 showing its binding mode with Hg2+ (Zhang et al. 2013)

Li et al. reported a PET naphthalimide-based probe, Hg-10 (Fig. 12), that bears a hydrophilic hexanoic acid group (as a solubilising functional group) for the monitoring of Hg2+ (Li et al. 2012). Experimental results revealed that the compound was most effective for the tracking of Hg2+ within the linear concentration range of 2.57 × 10−7–9.27 × 10−5 M. Job’s plot unveiled a 1:1 stoichiometric mode of Probe Hg-10 and Hg2+. The calculated detection limit was 4.93 × 10–8 M. In Tris-HNO3 buffer solution (pH = 7.0), the probe showed a massive enhancement in the intensity of its fluorescence upon Hg2+ addition in coexistence with several other investigated cations. The analytical detection response time of Hg2+ by Hg-10 was < 1 min. Hg-10 exhibited a regeneration ability in its sensing mechanism as ascertained by the release of the unbound probe upon the addition of EDTA to the Hg-10/Hg2+ complex. The probe was successfully used for Hg2+ monitoring in hair samples.

Structure of Probe Hg-10 (Li et al. 2012)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on rhodamine fluorophore

Since they possess excellent photophysical properties, rhodamines have enjoyed wide applications as fluorescent probes and molecular markers. Rhodamine dyes, which belong to the xanthene class of dyes, represent one of the oldest synthetic dyes used for fabric dyeing. They possess high molar absorptivities in the visible region, and many of their derivatives exhibit strong fluorescence. Moreover, there is a strong influence of their absorption and emission properties by substituents in the xanthene nucleus, thereby making them useful not only as colourants but also as fluorescent markers in photosensitisers, microscopic structural studies, and laser dyes (Arbeloa and Ojeda 1981).

Arivazhagan et al. designed two triazole-appended ferrocene–rhodamine conjugates, C47H45N7O3Fe (Hg-11) and C49H49N7O3Fe (Hg-12) (Fig. 13), synthesised as probes for a highly ‘turn on’ fluorescence detection of Hg2+ in CH3CN/HEPES buffer (2:8, v/v, pH 7.3, 10 μM) (Arivazhagan et al. 2015). It was shown that receptors Hg-11 and Hg-12 could be employed for Hg2+ monitoring in the near-neutral pH range of 7.3. Upon the addition of Hg2+ to the receptors Hg-11 and Hg-12, there was a massive enlargement of the fluorescence intensity, explained based on the spirolactam ring opening of the rhodamine moiety upon chelation with a cation. The addition of alkali, alkaline, transition, and heavier transition metal ions like Na+, Mg2+, K+, Ca2+, Cr2+, Mn2+, Fe2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Pb2+, Cd2+, and Tl+ effected almost no influence on the fluorescence emission spectrum of receptor Hg-11, which was further confirmed by competitive experiments, thereby demonstrating the high affinity of receptor Hg-11 for Hg2+. The same trends of observations went for receptor Hg-12. Desirably, experimental results revealed that the receptors were reversible in their monitoring of Hg2+. Since the receptors could image Hg2+ ion in living cells using the MTT (5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay without any destruction, their potencies to track intracellular Hg2+ ions in MCF-7 breast cancer cells were successfully assessed via fluorescent imaging studies (Fig. 14).

Structures of Probes Hg-11 and Hg-12 (Arivazhagan et al. 2015)

Fluorescence and bright-field images of MCF-7 cells. a Fluorescence image of MCF-7 cells incubated with Hg-11 (10 μM) for 2 h at 37 °C (left) or Hg-12 (10 μM) for 2 h at 37 °C (right). b Bright-field image of Hg-11-treated MCF-7 cells (left) or Hg-12-treated MCF-7 cells (right). c Fluorescence image of MCF-7 cells incubated with Hg-11 (10 μM) for 30 min and then treated with (10 μM) Hg(ClO4)2 for 2 h at 37 °C (left) or Hg-12 (10 μM) for 30 min and then treated with (10 μM) Hg(ClO4)2 for 2 h at 37 °C (right). d Overlaid images of MCF-7 cells (b, c) (left: Hg-11; right: Hg-12) (Arivazhagan et al. 2015)

Chen and members of his research laboratory reported a water-soluble fluorescent probe, Hg-13 (Fig. 15), constructed from rhodamine B derivative (Chen et al. 2013b). The new probe displayed both colourimetric (‘naked eye’) detection and fluorescent response towards Hg2+ in a fully aqueous HEPES buffer solution. The optimum experimental pH range for the sensing of Hg2+ by Hg-13 was found to be 6–11. At 586 nm, a sizeable fluorescent escalation of about 1500-fold increment was noted upon Hg2+ addition to the solution of the probe in the presence of other alkali, alkaline earth, and transition metal ions (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cr3+, Fe3+, Fe2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Ag+, Co2+, Ni2+) investigated under identical testing conditions. Association constant of 1.21 × 105 M−1 was estimated from the binding interaction of the probe and analyte metal ion. Besides the linearity of the relationship between the probe and Hg2+, Job’s plot yielded a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio of the probe and the metal ion in the Hg-13/Hg2+ complex. The reversibility nature of the probe was demonstrated after the addition of EDTA to the complex’s solution, which led to the release of free Hg-13 compound from the bound Hg-13/Hg2+ complex. A fast response time (there was no apparent time delay) was demonstrated in the tracking of Hg2+ by Hg-13 as justified by the results of the real-time analysis. Utilising the fluorescence imaging experiments, the biological utility of Hg-13 demonstrated its ability to image Hg2+ in living HeLa cells whereby an MTT assay gave cell viability of 95% after treatment with 10 μM of the compound after 24 h of incubation.

For fluorescence detections of cations, it has been purported that virtually all rhodamine spirolactam fluorescent probes employ the spiro ring-opening reaction either through metal ion coordination or metal ion-catalysed desulphurisation reaction. Having utilised a Hg2+-triggered domino reaction, Gong and his co-workers described the synthesis of a novel rhodamine thiospirolactam derivative, Hg-14 (Fig. 15), as an ‘off–on’ fluorescent probe for the detection of Hg2+ in neutral H2O-MeOH (80/20; v/v) solution (Gong et al. 2012). Compound Hg-14 showed stability of response for Hg2+ sensing from 1.0 × 108–1.0 × 106 M. The fairly stable pH range of 3.0–11.0 was chosen for the conduct of the experiments. The fluorescence emission intensity of the rhodamine derivative Hg-14 underwent a marked increment (of about a 580-fold fluorescence improvement) upon the addition of 1 mM Hg2+. Contrastingly, the addition of 1 mM of Ag+ and 50 mM of the coexisting cations left no noteworthy influence on the probe’s fluorescence intensity. Whilst Probe Hg-14 showed linearity of detection response in the range of 10 nM–1 mM and an ultralow detection limit of 3 nM, its response time towards Hg2+ was not up to 6 min. As much as the opposite might have been desired, the reported compound Hg-14 was irreversible in its sensing nature towards Hg2+ (i.e. it was a chemodosimeter but not a probe), although it could bioimage Hg2+ in living HeLa cells with great sensitivity.

Hu and his teammates developed a simple yet effectual novel fluorescent compound, Hg-15 (Fig. 15), that anchors the thiorhodamine 6G-amide moiety by the employment of Hg2+-induced desulphurisation reaction and spirolactam opening of rhodamine (Hu et al. 2013). The compound, which functions as a chemodosimeter rather than as a probe, could detect Hg2+ in the broad and stable pH range of 6.0–10.0, although with the optimums pH range being 7.2–7.6. In 0.01 M HEPES-buffer ethanol solution (EtOH/H2O 1:8, v/v, pH = 7.4) solution, the proposed compound Hg-15 revealed a remarkable increase in its fluorescence intensity only upon contact with Hg2+ in the co-presence of several other cations, which induced neither an individual nor a collective effect(s) on the fluorescence intensity of Hg-15. 5-min response time for the monitoring of Hg2+ by Hg-15 was observed. The Job’s method of continuous variation gives a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio between Hg-15 and Hg2+ in the Hg-15/Hg2+ complex. An estimated detection limit of 4.2 × 10–8 M was obtained, and Hg-15 was successfully demonstrated as capable of monitoring Hg2+ in living cells via confocal laser scanning microscopy (CSLM).

Based on the spirolactam ring-opening process, Kumar et al. documented the rhodamine B phenyl hydrazide probe, Hg-16 (Fig. 16), being developed as a novel colourimetric and fluorescent chemodosimeter, for the sensitive, selective, and irreversible Hg2+ monitoring (Kumar et al. 2014). The fluorescence emission intensity was quite stable in the pH range of 7–12 upon the addition of various anions and cations. The compound which has the capability for naked-eye detection (from colourless to pink) of Hg2+ also displayed a substantial fluorescence increase in its emission intensity. At 580 nm, there was a significant strengthening of the fluorescence emission intensity of Hg-16 upon the addition of Hg2+ amidst several other cations and anions like Ca2+, K+, Mg2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Fe3+, Cu2+, Cl−, NO2−, NO3−, S2−, SO42−, and ClO− analysed. The linear detection response lied within the range 1–100 nM, with a detection limit of 0.019 nM calculated. The monitoring of Hg2+ by the probe was complete after about 1.5 min of the start of the reaction. The efficacious amphiphilic and fluorescence qualities of the designated compound Hg-16 were taken advantage of to bioimage Hg2+ in living MCF-7 cells by fluorescence microscopic studies. Table 1 summarises the analytical properties of Probe Hg-16 for Hg2+ detection.

Wang and colleagues devised a rhodamine-based compound, Hg-17 (Fig. 16), that anchors the thiospirolactam and benzimidazole moieties (Wang et al. 2012). The probe, which utilises the spirolactam ring-opening and desulphurisation process, functioned as a highly sensitive and selective ‘naked-eye’ chemodosimeter for Hg2+ sensing. In CH3CN-HEPES buffer (0.01 M, pH 7.4) (3:7, v/v), the fluorescence intensity of the reported compound underwent a sharp increase in the order of 180-fold enlargement when Hg2+ was added to the probe solution, which was attributed to the selective spirolactam ring-opening process followed by desulphurisation. The other added cations like Zn2+, Pb2+, Cd2+, Co2+, Hg2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Ag+, Al3+ and Cr3+ Zn2+, Pb2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Ag+, Li+, Mn2+, Na+, Fe3+, Al3+, and Sr2+ induced no influence on the probe’s fluorescence emission intensity. The estimated analytical detection limit was found to be 7.4 nM.

Utilising a rosamine scaffold, Taki and co-workers gave an account of the purportedly strongest reversible fluorescent probe compound, Hg-18 (Fig. 17), designed for Hg2+ sensing (Taki et al. 2012). In 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.20, 0.1 M KNO3) and DMSO (4:1, v/v), Hg-18 showed a stringent attraction towards Hg2+ amidst other foreign cations like Ni2+, Mn2+, Fe3+, Pb2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, and Co2+ with an ensuant 20-fold fluorescence increment observed. Cu+ and Ag+ interfered in the sensing of Hg2+ by Hg-18, although this was quite minuscule. The existence of a 1:1 stoichiometry between the probe and Hg2+ was demonstrated by the analysis of the result of the Job’s plot. The dissociation constant of 1.04 ± 0.05 × 10–16 M was calculated for the generation of the complex between the said probe compound and Hg2+ analyte ion. The imaging ability of Hg-18 for Hg2+ HeLa cells was feasible.

Structure of Probe Hg-18 (Taki et al. 2012)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on coumarin fluorophore

The coumarins, or benzo-α-pyrones, constitute a huge and important class of organic compounds. The structure of the simplest coumarin is made up of fused pyrone and benzene rings, with their position 2 harbouring a pyrone carbonyl group. Coumarins are naturally abundant, with the first coumarin isolated in 1820 from a bean variety, and with several other coumarin derivatives isolated from diverse plant species. The coumarins family exhibits exciting fluorescence properties, including high sensitivity to their local environment—in terms of both polarity and viscosity. This, in turn, led to their extensive application range desirably as sensitive fluorescent probes in a wide range of systems (Wagner 2009; Reddie et al. 2012).

Since the successful synthesis of the first thiocoumarin-derivative fluorescent probe for Hg2+ detection which exploits the desulphurisation of thiocoumarin to coumarin (Choi et al. 2009), there has been an upsurge in the subsequent synthesis of more such probes. Drawing inspiration from this, Qin and co-workers (Qin et al. 2018) disclosed a new ICT-based colourimetric and ratiometric fluorescent chemodosimeter, Hg-19 (Fig. 18), for Hg2+ monitoring. When excited at 477 nm and 543 nm, the probe is selective and sensitive towards Hg2+ detection in PBS buffer solution (10 mM, pH 7.4, containing 1% DMSO) in the coexistence of several other analytically relevant cations investigated (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Cr3+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Ni2+, Pb2+, and Sn4+) . The probe’s analytical detection range was between 1.0 and 15.0 with a low detection limit of 1.85 ppb. Furthermore, the probe was successfully used for the fluorescence imaging of Hg2+ in live cells. The in vitro and in vivo application of the probe towards HeLa cells was ascertained.

Structure of Hg-19 (Qin et al. 2018)

Based on Hg2+-induced cyclisation reaction, a simple 7-hydroxycoumarin-based compound, Hg-20 (Fig. 19), which acts as a ‘turn-on’ probe for the sensing of Hg2+ in aqueous media (CH3CN/H2O = 9:1, pH 7.0), was developed by Gao’s laboratory members (Gao et al. 2012). The probe is most effective in its sensing nature between the pH value of 6.2 and 8.0, whilst it could also maintain enough stability in this range (Fig. 19). Results revealed that there was a tremendous improvement in the compound’s fluorescence intensity upon the addition of Hg2+. However, in the absence of the competing metal ions, there was an insignificant variation in Hg-20′s fluorescence intensity, except for the quenching effect displayed by Cu2+. The results of the competition experiments further justified the high sensitivity and selectivity of Hg-20 towards Hg2+. The presence of anions also impacted a little effect on the fluorescence response behaviour of Hg-20 towards Hg2+. Probe Hg-20′s detection limit for Hg2+ monitoring was calculated to be 5.12 × 10–7 M. The practical usage of the developed compound was demonstrated by its ability to measure Hg2+ in tap and well water samples.

Structure of Probe Hg-20 (left), and the changes in the fluorescence of Probe Hg-20 (black line) and Probe Hg-20 with Hg2+(red line) in buffer solution as a function of increasing pH value (10 μM CH3CN/H2O = 9/1, v/v, excitation wavelength = 328 nm, and emission wavelength = 400 nm) (right) (Gao et al. 2012)

Five structurally similar coumarin-based fluorescent probes, Hg-21–Hg-25 (Fig. 20), that could selectively and sensitively monitor Hg2+ were developed (Guo et al. 2015). The authors reported that Hg2+ detection proceeded through the Hg2+-promoted desulphurisation of the probes—a seldom-used method for the construction of fluorescent probes. All the five probes (especially Probe Hg-21) possess excellent selectivity and anti-interference properties towards Hg2+ from other co-existing cations present together in the aqueous phase (Fig. 21). The probes showed linearity in their detection mode towards Hg2+ over the wide concentration range of 0.06–1.50 mM (0.06–0.90 mM for Probe Hg-25). The probes have interesting biological properties towards Hg2+, and the authors tested the efficacies of the probes (especially Probe Hg-21 because of its superb sensitivity for Hg2+ unmatched by the other probes) on MCF-7 cells. The in vitro cytotoxicity experiment revealed that Probe Hg-21 had little cytotoxicity on MCF-7 cells’ proliferation within the 0–10 mM concentration range. The binding mechanism was purported to have occurred via the Hg2+-promoted hydrolysis desulphurisation.

Structures of Probes Hg-21–Hg-25 (Guo et al. 2015)

Visual fluorescence emission of Probe Hg-21 (1 mM) in the presence of several cations (200 mM, 2.0 mM for Hg2+) on excitation at 365 nm using a UV lamp at ambient temperature (Guo et al. 2015)

The design of a water-soluble probe, Hg-26 (Fig. 22), which bears a coumarin unit as the fluorophore and a vinyl ether group as the receptor was documented by Wu’s lab (Wu et al. 2017). When investigated in HEPES buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0), there was a remarkable magnification of the probe’s fluorescence intensity upon the addition of Hg2+. The low detection limit (0.12 M) of Hg-26 proves that the probe exhibits outstanding selectivity and sensitivity towards Hg2+. The sensing mechanism of the probe with Hg2+ was confirmed using proton NMR (Fig. 22). The practical application of the probe as an excellent monitoring tool was demonstrated by its ability to detect traces of Hg2+ in real water samples (Table 2).

The partial 1H NMR (400 M, d6-DMSO) spectra of Probe Hg-26 (I), Probe Hg-26 with Hg2+ after 1 h (II), and 7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin (III) (Wu et al. 2017)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on naphthalimide and rhodamine hybrid fluorophore

Employing rhodamine 6G and rhodamine B appended to 4-Bromo-1,8-naphthalic anhydride as the fluorophore whilst using ethylenediamine as the spacer, Fang and co-workers successfully developed Probes Hg-27 and Hg-28 (Fig. 23) (Fang et al. 2015). Such systems have been proven effective for the highly sensitive and selective sensing of Hg2+ in the joint existence of other metal ions when spectroscopically investigated in CH3CN/HEPES buffer (1:1, v/v, pH = 7.0). There was a 7.09-fold fluorescence enhancement when Hg2+ was added to a solution of Probe Hg-27 (Fig. 24), this being attributed to a Hg2+-chelated spirolactam ring opening. Meanwhile, the association constant and detection limit of Probe Hg-27 for Hg2+ monitoring are 8.31 × 105 M−1 and 7.91 × 10–7 mol L−1, respectively. The spectroscopic investigation of Probe Hg-28, a more water-soluble probe than Probe Hg-27, gave the association constant and detection limit of the binding of Hg-28 with Hg2+ as 4.36 × 105 M−1 and 5.46 × 10–6 mol L−1, respectively.

Structures of Probes Hg-27 and Hg-28 (Fang et al. 2015)

a Fluorescence titration spectra of Hg-28 (5 μM) in CH3CN/HEPES buffer (1:1, v/v, pH = 7.0) in the presence of different concentrations of Hg2+ (0–16 μM). Inset: the plot of fluorescence intensity at 525 nm versus [Hg2+]. The excitation wavelength was 450 nm. b Fluorescence titration spectra of Hg-28 (5 μM) in pure CH3CN in the presence of different concentrations of Hg2+ (0–24 μM). Inset: the image of fluorescence changes of Hg-28 (5 μM) before and after upon interaction with Hg2+ (24 μM) (Fang et al. 2015)

Xu’s laboratory synthesised Probe Hg-29 (Fig. 25), which was employed for the ratiometric detection of Hg2+ based on the FRET mechanism (Xu et al. 2017). Robust association constant of 2.75 × 105 M−1 was calculated, and minuscule detection limit of 0.059 μM was determined in EtOH/HEPES (v/v, 9:1, pH 7.0) in the analytical presence of other analyte ions, viz K+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Fe2+, Ni2+, Ba2+, Co2+, Na+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Ca2+, Cd2+, Ag+, Cr3+, and Hg2+. Thanks to its high recovery rate, real-time response, and anti-interference property, the probe was reportedly capable of being used for the ‘naked-eye’ Hg2+ monitoring and was also feasibly employed for Hg2+ monitoring in actual environmental water samples.

Structure of Probe Hg-29 (Xu et al. 2017)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on rhodamine and coumarin hybrid fluorophore

Utilising the multiple advantages of ratiometric FRET process as a sensitive, selective, and adaptable detection technique, Zhou et al. (2013) came up with a Hg2+-selective probe, Hg-30 (Fig. 26), built from the rhodamine–coumarin scaffold. This probe was designed to exhibit a dual-responsive fluorescent and colourimetric analytical detection (Fig. 26) when investigated for Hg2+ selectivity when jointly present with common cations like Fe2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Co2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, and Cr3+ in CH3CN/H2O system. Upon the addition of these metal ions, there was no noticeable change in the probe’s emission intensity. The designated probe was capable of the biological imaging of intracellular Hg2+.

Absorption (up) and fluorescent (down) spectra of Probe Hg-30 (2 μM) (inset) (HEPES/CH3CN, v/v = 20:80; pH 7.0) (Zhou et al. 2013)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on naphthalimide and coumarin hybrid fluorophore

Through a mercury-promoted desulphurisation of thiocarbonyl moiety, a FRET dyad, Hg-31, which bears both 1,8-naphthalimide and rhodamine B moieties, was constructed as a ratiometric fluorescent probe for Hg2+ detection (Liu et al. 2012). Compound Hg-31 (Fig. 27) is most appropriate for sensing application within the pH range of 5.7 to 11.0. Meanwhile, the linear range of fluorescence response detection was 4.2–10 mM, and the response time for the sensing investigation was 10 min. In (2:1, v/v) MeOH/H2O solution (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.0), there was a monumental fluorescence intensity increment in Hg-31 explained as due to the rhodamine B unit ring opening. Cations like K+, Na+, Fe2+, Mg2+, Cr3+, Fe3+, Ca2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, Cd2+, Ag+, Au3+, and Pb2 impacted zero changes on the fluorescence intensity of Compound Hg-31, albeit there was a little interference induced by Ag+.

Structure of Probe Hg-31 (Liu et al. 2012)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on rhodamine and coumarin hybrid fluorophore

Through a spirocyclisation-modulated process, a rhodamine receptor was fused with a 7-diethylaminocoumarin fluorophore to develop a NIR ratiometric fluorescent Probe Hg-32 (Fig. 28) (Liu et al. 2013a). The designed compound was stable in the long pH range of 1 to 12: When Hg2+ was increasingly added to the solution of the probe in Tris–HCl/CH3CN (10 mM, pH = 7.4, 1:1, v/v) amidst cations like, K+, Na+, Mg2+, Cu2+, Ca2+, Fe2+, Zn2+, Fe3+, Ni2+, Cr2+, Mn2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, Ag+, and Co2+, there was a massive downward shift in the fluorescence intensity at 480 nm, only for a new emission band positioned at 695 nm to appear. Desirably, the sensing reaction showed completion only after about 10 s of the starting time. A commendable linear ratiometric response (I695/I480) of Hg2+ monitoring was observed in the concentration range of 0–30 mM with a detection limit of 2.8 × 10–8 M estimated. Probe Hg-32 could image Hg2+ in living HeLa cells.

Synthetic pathway to fluorescent Probe Hg-32 (Liu et al. 2013a)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on rhodamine and pentaquinone hybrid fluorophore

Based on a TBET paradigm, Bhalla et al. documented the first instance of pentaquinone derivatives, Hg-33 and Hg-34 (Fig. 29), joined with a rhodamine unit devised for the ultra-high selective and sensitive tracking of Hg2+ (Bhalla et al. 2012). The optimum working pH range of the compounds Hg-33 and Hg-34 is 4.0–7.0. In THF/H2O (9.5:0.5, v/v), only Hg2+ led to the enhancement of the fluorescence intensities of Hg-33 and Hg-34 (56-fold and 160-fold increment, respectively) in the midst of the other co-existent metal ions. The sensing performances of Hg-33 and Hg-34 were not affected by counter anions, except for NO3− that left a slight decrement in the sensing property of receptor Hg-34. The method of continuous variation, i.e. Job’s plot, furnishes 1:1 and 1:2 stoichiometric ratios of Hg2+ interaction with receptors Hg-33 and Hg-34, respectively. The calculated detection limits of receptors Hg-33 and Hg-34 for Hg2+ monitoring are 5 × 10–6 and 7 × 10–7 M, respectively. The receptors Hg-33 and Hg-34 displayed reversibility in their Hg2+ abilities. The receptor Hg-34 was successfully appraised for in vitro Hg2+ monitoring in prostate cancer (PC3) cell lines.

Structures of Probes Hg-33 and Hg-34 (Bhalla et al. 2012)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) fluorophore

The 4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diazas-indacene molecule whose structure can be easily tuned at the carbon positions 1,3,5,7, and 8 is termed boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) chromophores, the BODIPY itself being registered under the trademark of Molecular Probes Inc. (Keller et al. 1995; Schade et al. 1996; Jones et al. 1997; Durand et al. 2000; Marme et al. 2003; Traverso et al. 2003). Treibs and Kreuzer 1968 reported the first BODIPY chromophore. The useful photophysical characteristics of BODIPY-based probes have led to their increasing usage. There is operational ease in the tuning of their visible excitation and emission by simply modifying the pyrrole core (Loudet and Burgess 2007; Thoresen et al. 1998; Rurack et al. 2001). They also possess high fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF ≈ 1.0, even in water), high molar absorption coefficients (typically log max > 8.8), narrow emission bandwidths, and excellent photostability. They lack a net ionic charge, and their fluorescence is insensitive to solvent or pH. All these desirable properties constitute additional advantages (Sathyamoorthi et al. 1994; Treibs and Kreuzer 1968; Haugland et al. 1988).

Maity’s lab documented a fluorescent probe for Hg2+, Hg-35 (Fig. 30), which incorporates a 2,2′-(ethane-1,2-diylbis(oxy))bis(N,N-bis(pyridine-2-ylmethyl)aniline receptor moiety built from a BODIPY derivative (Maity et al. 2015). Hg-35 exhibited a large variation in its fluorescence within the pH range 4–8. The compound showed both selectivity and sensitivity towards Hg2+ (or Cd2+) when present with an array of other cations such as Li+, K+, Na+, Mn2+, Mg2+, Co2+, Ca2+, Fe2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, and Ag+ in 20% DMSO-H2O medium. The compliance of the selectivity of the compound for Hg2+ was justified by the great fluorescence enhancement noticed upon the addition of Hg2+. The analysis of the Job’s plot yielded a 1:1 binding stoichiometry of the Hg-35/Hg2+ complex. The estimated value of the association constant is 1.8 × 105 M−1 for Hg2+ (and 3.77 × 104 M−1 for Cd2+), and a detection limit of 38 nM was obtained. Compound Hg-35 detected Hg2+ (or Cd2+) well enough in living cells.

Structure of Probe Hg-35 (Maity et al. 2015)

The BODIPY derivative, Hg-36 (Fig. 31), is a fluorescence probe developed for the highly sensitive and selective monitoring of Hg2+ in CH3OH (Vedamalai 2012). An array of cations (Ag+, K+, Cd2+, Ca2+, Co2+, Fe2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, and Pb2+) was used to assess the interference property of the compound in the detection of Hg2+. Desirably, these cations impacted only a meagre effect on Hg-36′s fluorescence emission intensity. The apparent dissociation constant of Hg-36/Hg2+ was calculated to be 62 μM. The sensing property of Hg-36 was tested by mixing it with other cations like Ag+, Ca2+, Cd2+, Co2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, K+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, and Zn2+. Experimental results revealed that the fluorescence emission intensity of the BODIPY derivative underwent a substantial increase upon the addition of Hg2+, but remained unperturbed when other metal ions were added. Job’s method indicated a 1:1 binding ratio between the detecting compound and the detected ion. The dissociation constant of 62.1 ± 5.7 μM was obtained. Meanwhile, a detection limit of 2.8 μM was estimated. Utilising the fluorescence rationale, Hg-36 proves very suitable for Hg2+ tracking in living HeLa cells.

Structure of Probe Hg-36 (Vedamalai 2012)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on cinnamaldehyde fluorophore

Kumar and co-workers synthesised a PET fluorescence ‘turn-on’ probe, Hg-37 (Fig. 32), that anchors N,N-dimethylaminocinnamaldehyde, for the monitoring of Hg2+, whereby the as-prepared complex Hg-37/Hg2+ was further engaged for the detection of picric acid (Kumar et al. 2012b). In THF/H2O (9:1, v/v), recognition and competitive experiments revealed that the addition of metal ions to the probe’s solution did not induce any substantial change in the fluorescence intensity of the probe, except for Hg2+ that impacted a fluorescence quenching phenomenon. The experimental result provides a detection limit of 80 × 10–9 M for Hg2+ tracking by the designed compound. Both the linear regression analysis (SPECFIT programme) and Job’s plot indicated a 1:2 stoichiometry of chelation between the probe and Hg2+ and a binding constant of 9.16 ± 0.03 was estimated. It was demonstrated that the interaction between Hg2+ and compound Hg-37 was reversible.

Structure of Probe Hg-37 (Kumar et al. 2012b)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on Schiff base fluorophore

The Schiff base reaction was conceptualised in 1864 by the German chemist, Hugo Schiff, which is a reaction between aldehyde- or ketone-containing compounds and amino groups, leading to the generation of imine groups (–CN–) (Fig. 33). The set of reactions constitute popular chemical reactions due to that their reaction conditions are mild and that their reaction rates are high (Jia and Li2015). Only in the past few years had Schiff base compounds become increasingly applied for the generation of fluorescent and colourimetric probes.

Schematic demonstration of Schiff base reaction (Jia and Li 2015)

Mandal et al. constructed a series of new imine-based probes, Hg-38, Hg-39, and Hg-40 (Fig. 34), for the sharp fluorescence ‘turn on’ detection of Hg2+ in CHCl3/CH3CN (1:4, v/v) over other competing metal ions (Mandal et al. 2012). There was a monumental increase in the fluorescence intensities of Hg-38, Hg-39, and Hg-40 upon interaction with Hg2+, this being explained as owing to imine isomerisation and inhibited PET mechanism. The composite binding constants of Hg2+ by Hg-38, Hg-39, and Hg-40 were obtained to be 2.79 × 109 M−2 L2 (for Hg-38) and 1.29 × 109 M−2 L2 (for Hg-39 and Hg-40). Meanwhile, the analysis of the Benesi–Hildebrand plots for Hg-39 and Hg-40 gave a 2:1 stoichiometric ratio. Hg-38 was reversible in its sensing of Hg2+ after the addition of KI that led to the recovery of the unbound probe compound from the Hg-38/(Hg2+)2 complex. Interestingly, Hg-38 and Hg-39 were successfully demonstrated for Hg2+ detection in living cervical cancer HeLa cells.

Structures of imine-based Probes Hg-38, Hg-39, and Hg-40 (Mandal et al. 2012)

Quang reported the synthesis of the ICT aminothiourea-derived Schiff base, Hg-41 (Fig. 35), for the fluorescent recognition of Hg2+ (Quang et al. 2013). In aqueous solution, the addition of Hg2+ to the probe’s solution pushed the fluorescence intensity upward at about 30% increment. Contrastingly, competitive cations like K+, Cd2+, Pb2+, Cr3+, Fe2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Co3+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and Na+ led to benign variation in the fluorescence of Hg-41. The most desirable working pH range of Hg-41 for Hg2+ determination was from 5 to 9. Moreover, the time required for the reaction to be complete was 30 s. A 2:1 complex of Probe Hg-41 and Hg2+ was derived, which was confirmed by the result of the ESI–MS.

Proposed interaction mechanism between Probe Hg-41 and Hg2+ (Quang et al. 2013)

The novel and elegant pyrene-based free thiol probe, Hg-42 (Fig. 36), that bears the Schiff base was documented by Shellaiah and co-workers (Shellaiah et al. 2015). The developed compound, which utilises a reversible chelation-enhanced fluorescence (CHEF) mechanism, was engaged as a fluorescence ‘turn on’ probe for the tracking of Hg2+ ion in DMSO/H2O (v/v = 7/3; pH 7.0). The original, strong fluorescence of the devised probe was enhanced when Hg2+ was added to it, whereas other cations including Na+, Ag+, Ni2+, Co2+, Fe3+, Zn2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, Cr3+, Cu2+, Mg2+, Hg2+, Mn2+, Fe2+, and Al3+ did not impact a noticeable effect on the fluorescence intensity of the probe, in either single or dual metal analyses. The only exception was Pb2+ and Cd2+ that interfered somewhat weakly. Job’s plot analysis gives a distinct 2:1 binding ratio of the derived probe-Hg2+complex. The detection limit and association constant are 2.82 × 10–6 M and 7.36 × 104 M−1, respectively. Desirably, the usage of Hg-42 for Hg2+ imaging in living HeLa cells was successfully established.

Structural representation of Probe Hg-42 (Shellaiah et al. 2015)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on anthracene fluorophore

Srivastava and teammates synthesised an effective PET compound, Hg-43 (Fig. 37), which anchors anthracene and benzhydryl moieties via a piperazine bridge, as a fluorescent molecular probe for Hg2+ sensing (Srivastava et al. 2014). There was observed a large increase in the fluorescence intensity of ca. tenfold in HEPES buffer and ca. 15% in CH3CN-H2O solution, with a consequential colour change from blue to blue-green. Other cations (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Zn2+, Pb2+, Ag+, Cd2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+ Fe2+, Fe3+, Mg2+, Ca2+, and Zn2+) did not engender any noteworthy influence on the fluorescence intensity of Hg2+, except for Fe3+ that interfered quite slightly (ca. 5 to 7%) on Hg-43′s fluorescence emission intensity. The probe existed with Hg2+ in Hg-43/Hg2+ complex in a 1:2 stoichiometry. Hg-43 was found to be pH insensitive within the range 7–14, with pH 5 being the optimal pH value. Job’s plot analysis revealed a 1:2 stoichiometric binding interaction between Hg-43 and Hg2+. The association constant and detection limit were obtained as 1.06 × 1010 M−2 and 10 nM or 2 ppb, respectively. The probe Hg-43 was successfully applied as a solid probe for Hg2+ monitoring on solid surfaces like paper strips and slides coated with silica, as well as to bioimage Hg2+ in HeLa cells.

Structure of Probe Hg-43 (Srivastava et al. 2014)

Praveen and co-workers constructed the anthracene-oxyquinoline dyad, Hg-44 (Fig. 38), for Hg2+ sensitive and selective sensing (Praveen et al. 2012). In MeCN-H2O system, Hg2+ addition quenched the fluorescence of the reported compound, a phenomenon unobserved in the cases of other co-existed cations. A 1:1 binding stoichiometry was provided by the analysis of the Job’s plot, whilst a detection limit of 3.2 × 10–6 M was calculated from the Benesi–Hildebrand plot. Probe Hg-44 was reversible in its tracking of Hg2+.

Plausible binding mode of Probe Hg-44 with Hg2+ (Praveen et al. 2012)

A new anthracene-based sensing modality, Hg-45, 1-(Anthracen-2-yliminomethyl)-napthalen-2-ol (AIN) (Fig. 39), which features aggregation-induced emission (AIE) was recently disclosed by Shyamal’s group (Shyamal et al. 2018). The probe exhibited a suppression in its fluorescence intensity upon selective recognition of Hg2+ with a linearity of response within the concentration range 0.3–3.6 M. The sensing ability of the probe was tested in THF/H2O (7:3, v/v) in the presence of various relevant metal ions. The probe’s sensitivity was excellent (a limit of detection limit of ca. 3 ppb was estimated), and the quenching constant obtained from Stern–Volmer equation was 2.54 × 105 M−1. The probe’s ability to quantify Hg2+ concentration in real water samples was successfully investigated.

Structure of Probe Hg-45, 1-(Anthracen-2-yliminomethyl)-napthalen-2-ol (AIN) (Shyamal et al. 2018)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on squaraine fluorophore

The squaraines are a subclass of the polymethine dyes possessing a zwitterionic structure and constituting one of the most fascinating groups of dyes for the preparation of near-infrared fluorescent probes (Oswald et al. 2000; Kukrer and Akkaya 1999; Dilek and Akkaya 2000). They exhibit outstanding physicochemical properties, including magnificent and sharp absorption bands, (detectable in the visible and NIR regions) as well as intense fluorescence bands (Welder et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2002). These properties make the squarylium fluorophores suitable for sensing purposes. Infusion of substituents into the aromatic ring or on the N atom of the terminal heterocyclic moiety could lead to their structural modifications. Such variations can be used to produce a red shift of the absorption and fluorescence bands.

Fan and teammates developed the squaraine-appended colourimetric and fluorescent probe, Hg-46 (Fig. 40) (Fan et al. 2012), for Hg2+-sensitive and selective sensing. In ethanol–phosphate buffer (EtOH/PB) (50:50, v/v) solution, Hg2+ addition amidst several other metal ions led to a gradual dampening of the probe’s fluorescence intensity. Job’s plot analysis indicates the formation of a 1:1 binding stoichiometry. The calculated association constant and detection limit are 3.05 × 103 M−1 and 1.3 × 10–7 M, respectively. Experimental outcomes demonstrated Hg-46 as reversible in its sensing mode, i.e. the unbound Hg-46 was regenerated upon EDTA addition to Hg-46/metal complex’s solution.

Structure of the squaraine Probe Hg-46 (Fan et al. 2012)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on pyrene fluorophore

Weng and laboratory members reported a compound, Hg-47 (Fig. 41), that anchors the pyrene skeleton and diazene architecture (Weng et al. 2012). The designated compound acts as a useful fluorescent probe for tracking Hg2+. In CH3CN solution, the addition of various cations did not incite any tremendous change in the fluorescence of Hg-47, whereas the addition of Hg2+ led to a marked decrement in the fluorescence of Hg-47, affirming the affinity of the designed probe for Hg2+ even in competition with other analytically investigated cations. A 2:1 stoichiometric ratio of the interaction of the probe and Hg2+ was furnished by Job’s plot analysis, which was corroborated by MS and NMR experimental results. The detection limit was calculated to be 4.69 × 10–6 M.

Possible binding mechanism of Probe Hg-47 with Hg2+ (Weng et al. 2012)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on rhodamine and pyrene hybrid fluorophore

Being informed by the knowledge that rhodamine and pyrene scaffolds exhibit excellent optical and configurable characteristics, Rui et al. developed two rhodamine–pyrene conjugated probes, Hg-48 and Hg-49 (Fig. 42) (Rui et al. 2016), which display strong affinities to Hg2+ via FRET process in the existence of other cations tested in EtOH/H2O (1:1, v/v, pH 7.0). The detection limit of sensing of Hg2+ by Probes Hg-48 and Hg-49 is 4.34 × 10–7 mol L−1 and 1.91 × 10–5 mol L−1, respectively. The experimental results showed that Probe Hg-48 is a better probe than Probe Hg-49 due to its shorter response time, lower detection limit, and reversibility. Moreover, Probe Hg-48 was effectively employed for Hg2+ tracking in real water samples.

Structures of Probes Hg-48 and Hg-49 (Rui et al. 2016)

Two rhodamine–pyrene probes, Probes Hg-50 and Hg-51 (Fig. 43), were synthesised by Chu’s laboratory (Chu et al. 2013). In EtOH/H2O (2:1, v/v), both these probes exhibited outstanding sensing properties towards Hg2+ when tested in the analytical presence of commonly tested cations. The limit of detection of Probe Hg-50 for Hg2+ monitoring was quantified as 0.72 μM, whilst that of Probe Hg-51 was obtained as 5.3 μM. Meanwhile, the association constants of these two probes for Hg2+ monitoring were 2.74 × 105 M−1 and 1.56 × 105 M−1, respectively. It was experimentally confirmed that Probe Hg-50 had better spectral properties than Probe Hg-51, in terms of higher selectivity, excellent reversibility, and lower detection limit than Probe Hg-51, due to the thiophilic property of Hg2+. Finally, the utility of Probe Hg-50 for Hg2+ detection in practical biological systems was successfully demonstrated.

Structures of Probes Hg-50 and Hg-51 (Chu et al. 2013)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on azo derivative fluorophore

Tian et al. documented an azo derivative, Hg-52 (Fig. 44), based on alkynes, which served as a colourimetric and fluorescence probe for the detection of Hg2+ (Tian et al. 2014). The probe gave no fluorescence emission in aqueous solution, which is atypical of the azo group of probes. But the addition of Hg2+ amongst several other cations and anions led to a 168-fold increase in the probe’s fluorescence intensity. The Job’s plot provided a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio in the interaction of Hg-52 with Hg2+. The detection limit and association constant of the probe for the sensing of Hg2+ were calculated as 46.50 nM and 3.96 × 106 M1, respectively. The sensing mechanism of Hg2+ by Hg-52 was demonstrated reversible by the addition of Na2S. The specificity of Probe Hg-52 towards Hg2+ was determined by fluorescence screening. Hg-52′s potency to track Hg2+ was successfully demonstrated in living HT-29 cells.

Yu and co-workers designed a thioacetal probe, Hg-53 (Fig. 44), that anchors both carbazole and azobenzene units (Yu et al. 2016). The spectroscopic characterisation of the compound showed that it functioned effectively in the range of 0–2.5 M and possessed a short response time of 30 s. In CH3CN/H2O solution, various cations (including Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Ni2+, Li+, Co2+, Ag+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Mn2+, Cr3+, Fe3+, Zn2+, Cd2+, Sr2+) impinged no monumental change in Hg-53′s fluorescence intensity except for Hg2+ that led to a dramatic increment in the fluorescence intensity of the designated compound (about a 24-fold increase). Job’s plot indicates a 1:1 binding stoichiometry between the probe Hg-53 and Hg2+. A detection limit of 1.80 × 10–8 M was calculated.

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on benzimidazole derivative fluorophore

Hu et al. (2015) reported on a novel Hg2+ non-sulphur fluorescent probe, Hg-54 (Fig. 45) that incorporates the benzimidazole and quinoline moieties as the fluorescence signal groups. The compound exhibited a sharp distinguishing ability for Hg2+ over an array of other divalent cations as monitored by fluorescence spectroscopic analysis in H2O/DMSO (1:9, v/v) solution with a massive colour change from blue to colourless observed when Hg2+ was added to the probe’s solution in aqueous media. Similar experiments for competitive cations present did not induce any prominent variation in the colour. The analytical limit of detection of the fluorescence response of the probe to Hg2+ is low down to 9.56 × 10–9 M. The usage of the probe in the fabrication of test kits which could monitor Hg2+ demonstrated the probe’s practical application utility in an aqueous environment.

Synthetic route to Probe Hg-54 (Hu et al. 2015)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on the phenanthroline fluorophore

Shan and co-workers developed a fast, responsive, and highly selective Hg2+ probe, Hg-55 (Fig. 46), based on 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline (2,9-DMP) fluorophore (Shan et al. 2016). The selectivity and sensitivity experiments were carried out in Tris-HNO3 at the optimum sensing pH value of 2.0. The probe’s response to Hg2+ was rapid and selective within a good linear range of 0.05–2.00 µM. The reported compound was then utilised to monitor concentrations of Hg2+ in aqueous samples of drinking water and Zhujiang River water. Excellent recoveries of 85.42–101.5% and 81.72–96.09%, respectively, were obtained for each of these samples. Fluorescence titration experiment gave a 1:1 complex, demonstrating a 1:1 stoichiometric mode between the probe and Hg2+. This was then further evidenced by the results of Job’s plot and single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

Structure of 2,9-DMP fluorophore-based Probe Hg-55 (Shan et al. 2016)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on miscellaneous fluorophores

Because of limited space, it is difficult to cover all fluorophores used in the development of small-molecule Hg2+ probes in this review work. However, apart from the small-molecule Hg2+ probes highlighted above, other fluorophores such as cyanine and fluorescein (Fig. 47) (Zheng et al. 2013; Ando and Koide 2011; Liu et al. 2013b) have been employed as alternative receptors in design and synthesis of small-molecule Hg2+ probes. Zheng et al. (2013) provided an overview of fluorescent probes based on the xanthene scaffolds, predominantly the rhodamine and fluorescein moieties. The fluorescent behaviours of these probes towards diverse analytes, including mercuric ion (Hg2+) or methylmercury species (MeHg), were discussed. Ando and Koide (2011) developed a new vinyl ether Hg-selective probe by the reaction of an allyl ether and KOtBu in DMSO through the oxymercuration reaction. The probe, which functions best at pH 4 in 50 mM phthalate buffer, detects Hg2+ at ambient temperature (i.e. 25 °C) and can be applied for Hg2+ monitoring in river water and dental amalgam samples. A cyanine-modified nanoprobe (the cyanine dye was assembled on lanthanide UCNPs’ surface) which functions as a dual colourimetric and fluorescent probe for MeHg+ sensing was reported by Liu’s laboratory (2013b). This probe, whose sensing properties were largely uninfluenced by the presence of other non-mercuric cations, gave the detection limit of ca. 200 ppb. The probe showed great potential imaging applications in living cells and also for luminescence in vivo imaging.

The morpholine-based fluorophore possesses a lysosome-targeting capability and has been found efficient as a lysosomal localisation group. Informed by this, Zhang’s group developed a PET dual-functional colourimetric and ratiometric fluorescent probe, Hg-56 (Fig. 48), from the 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzo-2,1,3-oxadiazole (NBD-Cl) moiety (Zhang et al. 2016). The probe is water-soluble, bio-compatible and cell permeable, and could, therefore, monitor Hg2+-related cellular toxicological actions of HeLa cells.

Structure of Probe Hg-56 (Zhang et al. 2016)

Recently, Gu et al. and Ding and co-workers synthesised and evaluated the optical features of probes based on the 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)-9,10-phenanthroimidazole (HPI) and dithioacetal fluorophores, Hg-57 and Hg-58 (Fig. 49), respectively (Gu et al. 2015; Ding et al. 2015). Both these probes have superior binding properties towards Hg2+ in the coexistence of other analytically investigated cations.

The AIE feature of a π-conjugated cyanostilbene derivative of (Z)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-(vinyloxy)phenyl)acrylonitrile, Hg-59 (Fig. 50), was advantage taken of by Wang et al. in their design of a new sensing modality (Wang et al. 2015). The sensing properties of the designated probe compound were carried out in THF/H2O (2:8, v/v). Probe Hg-59 was selective towards Hg2+ amidst an array of metal ions concomitantly investigated, and the fluorescence intensity of Hg-59 was dampened in a linear fashion with the incremental addition of Hg2+ (0–50 μM). The selectivity property of the probe was then tested with the probe’s detection limit calculated as 37 nM. These good properties of the probe enabled the quantification of Hg2+ in real water samples, thereby lending validity to the probe’s good sensing ability.

Structure of Hg-59 (Wang et al. 2015)

Hg 2+ probes based on supramolecular fluorophores

The seminal work of Chen and co-workers (2017) represented the first case of the use of supramolecular polymers in sequestering toxic heavy metal ions. Their supramolecular system was prepared through self-assembly of a thymine-substituted copillar[5]arene, 1, (catcher) and a tetraphenylethylene (TPE) derivative, 2 (indicator), together with Hg2+. The reversible recognition studies of Hg2+ with the thymine moieties of 1 were investigated. The host–guest interaction between 1 and 2 was also examined, and the supramolecular complex/pseudorotaxane 2 ⊂ 1 was then used for Hg2+ tracking. Fluorescence titration experiments in the presence of other cations in 300 μM (CH3)2CO showed that there was a massive enhancement of the absorption maximum of 1 upon the incremental addition of 1.0 equiv. of Hg2+ coupled with a bathochromic shift from 326 to 329 nm. This was being accrued to the coordination of Hg2+ with the thymine moieties in 1, leading to the formation of T − Hg2+ − T pairings between 1 and Hg2+. TPE derivatives are known to only display strong fluorescence after aggregation; otherwise, they exhibit zero or low fluorescence when existent in a highly dispersed state. Springing from the AIE properties of 2, the derived supramolecular polymer exhibited strong fluorescence which was exploited for Hg2+ detection and removal. Linearity of fluorescence response in the range 0 − 180 μM was observed, and the analytical detection limit was 2.3 μM. The applicability of the 2 ⊂ 1 supramolecular system in removing Hg2+ from real water samples was successfully tested.

Taking advantage of supramolecular self-assembly, a new sensitive and selective probe, (E)-1-((5-(4-nitrophenyl) furan-2-yl)methylene) semicarbazone (Hg-60) (Fig. 51), was derived from fusing 5-(4-nitrophenyl)-2-furan (the fluorophore) with semicarbazide groups (Qu et al. 2014). In DMSO/H2O (8:2, v/v) HEPES buffer (pH = 7.2) solution, there was a dampening of the fluorescence intensity of the probe (20 μM) when Hg2+ (1 equiv.) was added in the presence of Fe3+, Hg2+, Ag+, Ca2+, Cu2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, Cr3+, and Mg2+ (20 μM). This observation was ascribed to the supramolecular self-assembly breaking and the cooperation reaction occurrence. The detection limit of Hg-60 for Hg2+ determination was 2.084 nM, whilst Job’s plot analysis furnished a 1:2 stoichiometric ratio between Hg-60 and Hg2+ in Hg-60–Hg2+. Test strips of the probe successfully tracked Hg2+ in solution.

Structure of Hg-60 (Qu et al. 2014)

Hg 2+ probes based on carbohydrate-appended resorufin fluorophore

Ma and co-workers, with the employment of a carbohydrate-based Ferrier carbocyclisation reaction, designed a water-soluble fluorescent probe, Hg-61 (Fig. 52), for the monitoring of Hg2+ through a ‘turn on’ mode of its fluorescence intensity (Ma et al. 2012). The probe’s stability was established within the wide pH range of 3.4–9.3; the best operational pH value of the designated probe was 7.4. Meanwhile, 15-min response time for the sensing of Hg2+ by the reported probe was achieved. The experimental pH range employed for the analytical experiments is 3.4–9.3. In pure H2O (20 μM, pH 6.0), the compound maintained no fluorescent character. However, when the pH changed to > 6.96 by the addition of PBS buffer, there was a sudden appearance of vibrant fluorescence intensity with an accompanying colour variation from colourless to purple. This is due to the formation of O-anionic compound from the resorufin in the probe. The incremental additions of Hg2+ (0–1.0 μM) incited a 25-fold enhancement of the compound’s fluorescence intensity. However, the addition of a dozen of cations including Ca2+, Cd2+, Co2+, Cu2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Zn2+, Ag2+, Pb2+, Fe3+, Fe2+, Ni2+ did not alter the fluorescence intensity significantly under the similar investigation conditions. The limit of detection of Probe Hg-61 for Hg2+ was quantified as 0.15 μM or 30 μg/L. The potent value of Compound Hg-61 was realised in its application to track Hg2+ analyte ion in the A549 cell line of a 5-day-old zebrafish and human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial origins (Fig. 53).

Structure of Probe Hg-61 (Ma et al. 2012)

Hg2+ fluorescence images in A549 cells and zebrafish with Probe Hg-61. Bright-field transmission image (AC) and fluorescence image (DF) of A549 cells pre-treated with 20, 20, and 100 μM of Probe Hg-61 for 24 h and then incubated with 0, 10, and 50 μM of Hg2+ for 60 min, respectively (under green light excitation). Zebrafish bright-field transmission image (G–I) and fluorescence image (J–L) pretreated with 30, 30, and 60 μM of Probe Hg-61 for 120 min followed by incubation with 0, 15, and 30 μM of Hg2+ for 30 min, respectively (under green light excitation) (Ma et al. 2012)

Small-molecule Hg 2+ probes based on polymer-embedded fluorophore

A novel water-soluble non-conjugated fluorescent polymer dots (PDs), G-PEI PDs, synthesised by reacting polyethylenimine (PEI) and glutathione (GSH) was disclosed from Luo’s laboratory in 2018 (2018). In Britton–Robinson buffer (0.04 M, pH 5.0), a selective, quenched fluorescence intensity was observed in the presence of Hg2+ amongst the sixteen cations, fourteen anions and natural organic matter humid acid analysed. The fluorescence titration data gave the analytical detection limit as 32 nM, meaning the probe could effectively monitor Hg2+ in the nanomolar concentration range. The probe displayed a linear response proportionally (0.1–100 μM) was reversible in its sensing mode and could track Hg2+ in river water samples.