Abstract

Intragastric balloon (IGB) is a minimally invasive and reversible therapy for weight loss with a good efficacy and safety profile. Introduced in the 1980s, IGBs have significantly evolved in the last couple of decades. They mechanically act by decreasing the volume of the stomach and its reservoir capacity, delaying gastric emptying, and increasing satiety leading to a subsequent weight loss. Despite the low rates of complications and mortality associated with IGBs, adverse events and complications still occur and can range from mild to fatal. This review aims to provide an update on the current scientific evidence in regard to complications and adverse effects of the use of the IGB and its treatment. This is the first comprehensive narrative review in the literature dedicated to this subject.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity is a complex disease, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality [1]. There are several measures to facilitate weight loss, ranging from diet, medications, and lifestyle modifications such as increased physical activity to endoscopic and surgical interventions [2,3,4]. Nevertheless, obesity is a complex disorder that mandates a multidisciplinary approach that is focused not only on weight loss but also on the improvements of certain metabolic parameters and other social and psychological factors that impact the well-being of this population. Intragastric balloons (IGBs) have been in use since the 1980s [5, 6] and are a minimally invasive and reversible therapy for weight loss with a good efficacy and safety profile [7, 8]. They have a restrictive mechanism on the volume of the stomach and its reservoir capacity. Also, they act by delaying gastric emptying and increasing both early and prolonged satiety leading to weight loss [9]. Most recently the IGB has been used as a bridge therapy where patients can be “bridged” to decrease their cardiovascular risk before a proposed bariatric surgical intervention and also as a bridge to heart transplantation [10].

Complications and adverse effects have arisen during the use and evolution of IGBs. These can be as mild as nausea and emesis, severe with the need for urgent or endoscopic intervention, or even fatal and can occur while using the device or during the insertion or removal of the IGB [11]. This comprehensive review aims to bring an update on the contraindications, adverse events (AEs), and the treatment of complications related to the use of the intragastric balloon.

Contraindications

The first step in preventing complications related to the use of an intragastric balloon is to recognize the contraindications to its use. They can be classified as absolute and relative contraindications [12].

Absolute

Patients with previous gastric surgery (in which there was significant anatomical distortion), active peptic ulcer disease (esophageal, gastric, or duodenal ulcers), gastroesophageal varices, and a massive hiatal hernia (> 5cm).

Relative

Angiectasias, eosinophilic esophagitis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive patients, patients with uncontrolled psychiatric disorders, and the use of anticoagulants.

The following are not considered contraindications:

Patients with Los Angeles (LA) class A and B esophagitis, chronic inactive gastritis, patients with benign and/or small hyperplastic polyps, and patients with positive Helicobacter pylori status.

Adverse Events Related to the Intragastric Balloon

A systematic review and meta-analysis about endoscopic bariatric therapies (EBTs) carried out by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Bariatric Endoscopy Task Force [8] analyzed safety-related data from 68 studies of patients treated with the Orbera balloon (single fluid-filled balloon). The most common AEs reported were pain and nausea, occurring in 33.7 and 29% of patients, respectively. The rate of early IGB removal was 7.5%.

Severe AEs were rare, with 1.4% of migration, 0.3% intestinal obstruction, 0.1% perforation, and a mortality rate of 0.08%. Half of the gastric perforations (4/8) occurred in patients with previous gastric surgery. In some countries, this antecedent is considered an absolute contraindication for intragastric balloon implantation [12].

A retrospective study [12] analyzing 41,866 patients with different types of IGB devices (78.2% Orbera; 12.4% Medicone; 4.5% Silimed; 2.5% Helioscopie; 2.4% Spatz) found that the rate of early removal of the device due to patient’s intolerance was only 2.2% (n = 928). In this study [12], the AEs included hyperinflation (0.9%, n = 371), spontaneous rupture (0.9%, n = 365), migration requiring surgical intervention (0.06%, n = 24), migration treated conservatively (0.20%, n = 79), gastric ulcers (0.3%, n = 141), and gastric ulcers requiring urgent balloon removal (0.07%, n = 28). Perforations occurred at a rate of 0.01% (n = 6) during IGB removal and at 0.03% (n = 14) during the balloon dwelling time. No perforations were reported during placement. Bleeding occurred in 0.15% (n = 59) of cases and fungal colonization was appreciated in 5.8% of cases. Of the 12 deaths reported (0.03%), three of them were directly related to the balloon (gastric rupture due to excess food intake in an otherwise healthy patient, bronchoaspiration due to incoercible vomiting 4 days after placement, and pulmonary thromboembolism).

Adaptation/Accommodation Period

Most patients experience symptoms of gastric accommodation during the initial period after placement of the IGB. The most common symptoms are nausea, emesis, dehydration, gastroesophageal reflux, belching, abdominal pain/cramps, dyspepsia, and constipation.

To alleviate these symptoms, it is recommended to all patients the use of over-the-counter analgesics (with the avoidance of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), and liquid or sublingual antiemetics such as ondansetron, dimenhydrinate, and scopolamine (Table 1). It is also recommended to start therapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) before the insertion of the balloon and to maintain this throughout the dwelling time of the balloon [12].

In more severe cases, are recommended to come into the hospital if they are experiencing dehydration, nausea, or persistent emesis. In most cases, this condition resolves with intravenous (IV) hydration and aggressive treatment of symptoms. If the patient’s condition does not improve, complications should be then investigated.

Persistent vomiting and pain, in the absence of complications, are the main causes of early removal of the device.

Spontaneous Rupture of Balloon, Migration, and Gastrointestinal Obstruction

The intragastric balloon can spontaneously rupture, migrate, and cause gastrointestinal obstruction (Fig. 1). The likelihood of rupture is greater when the device remains in use beyond the recommendation by the manufacturer.

To early identify a leakage or rupture of the IGB, some countries have used methylene blue in the filling solution as it will cause a change in the color of the urine (“greenish urine”), alerting the patient about this complication (Fig. 2). With this in mind, it is possible to identify the complication early and remove the balloon before migration.

Clinical manifestations that should draw the clinical suspicion of this complication include abdominal pain, abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting, dehydration, and the absence of passage of flatus and feces. The patient should also be instructed to notify about any change in the color of the urine (in case methylene blue was used in the filling solution).

Initial management should include nothing by mouth (NPO status), vigorous intravenous hydration, management of electrolyte imbalances (with hypokalemia being the most common), and insertion of a nasogastric tube (NGT). Antibiotic therapy in gastrointestinal obstruction is recommended in cases of intestinal ischemia, necrosis, or perforation. A complete blood cell count (CBC), basic metabolic panel (BMP), liver function tests (LFTs), lipase, and lactate should be ordered. Imaging tests should be considered whenever the suspicion of an obstructive syndrome arises. Simple abdominal X-rays may be useful, but a computer tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with oral and intravenous contrast is the gold standard.

Twenty-seven case reports of gastrointestinal obstructions caused by IGB migration [13] have been reported over the last 37 years. In most cases, the devices stayed longer than recommended. The obstructions were located mainly between the first portion of the duodenum and the terminal ileum, with only one case reported in the sigmoid colon. In 66% of the cases, the obstruction was treated by exploratory laparotomy, 15% by laparoscopy, 7% by endoscopy (upper endoscopy and deep enteroscopy), and 11% by percutaneous puncture of the IGB with an aspiration of the balloon contents and its subsequent elimination through the feces.

The definitive therapy should be determined by the location of the impaction, the severity of the obstruction, and the ability of the endoscopist to retrieve it [14]. Balloons that obstruct the duodenum are typically amenable to endoscopic retrieval, while impaction in the jejunum or ileum usually requires a surgical intervention (laparoscopic or open) [15]. In a few selected cases, it is also possible to aspirate the contents of the balloon by percutaneous puncture followed by its elimination in the feces [13]. Immediate surgical exploration is indicated in the suspicion of serious complications such as ischemia, necrosis, and perforation.

In cases of ballon impaction in the gastric antrum, the clinical picture is similar to an acute obstructive abdomen, and its management should be the same as suggested above. In these cases, definitive treatment may also be performed by upper endoscopy with careful removal of the balloon [16].

Gastrointestinal Ulcers and Gastrointestinal Bleeding

It is believed that the direct contact of the balloon with the gastric mucosa (causing changes in the production of prostaglandins) associated with the stretching of the mucosa for a long period (decreasing its blood supply by direct compression of the most superficial vessels) may contribute to the development of gastritis, erosions, lacerations, and ulcerations (Figs. 3 and 4) [17]. The main risk factors for these complications are the interruption of PPI therapy and the indiscriminate use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) during the dwelling time of the balloon.

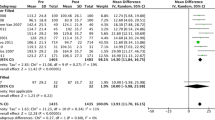

A systematic review with a meta-analysis that included 44 studies with a total of 5549 patients showed that the incidence of peptic ulcer disease is not affected by the volume of the IGB (from 400 to 700 ml) [18].

In general, ulcers are diagnosed during endoscopic balloon removal or when bleeding or perforation occurs. In cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, endoscopic evaluation and treatment followed by balloon retrieval are recommended.

Hyperinflation

Contamination of the filling fluid can occur during passage through the oral cavity during insertion or long exposure to food residues in a stomach with a pre-existing slow emptying. It is generally believed that an overgrowth of microorganisms of the genus Candida or other bacteria inside the balloon with its subsequent gas production through fermentation could cause hyperinflation of the balloon.

The diagnosis is made by severe and recurrent emesis, abdominal pain and distension, and the presence of a palpable abdominal mass. It is typically reported to be a delayed complication with some reports describing it as late as 5 months after insertion and with the use of high-dose PPIs as one potential contributor factor for it [19, 20]. X-rays typically show air-fluid levels inside the balloon and an increase in its dimensions (Fig. 5).

The treatment includes fasting, intravenous hydration, and symptomatic management. Nevertheless, the mainstay of treatment includes the removal of the balloon without the need for antifungal treatment. Delayed diagnosis can be complicated by a gastrointestinal obstruction, pancreatitis, and perforation [21].

Fungal colonization of the bezoar’s surface, uncomplicated with hyperinflation, can occur in 5.8% of patients and typically presents with mild symptoms, with halitosis being a remarkable feature of this (Fig. 6).

There is no current evidence or consensus about the benefits of using oral antifungals to prevent hyperinflation [12]. Therefore, its use is should include an individualized decision between the physician and the patient.

Pancreatitis

Mild to severe acute pancreatitis (AP) is a rare event that can occur at any time during the use of the device [22]. One possible explanation for this event is the extrinsic mechanical compression of the pancreas caused by the balloon (Fig. 7). The clinical picture includes the triad of intragastric balloon placement, clinical picture compatible with AP, and biochemical or radiological evidence of pancreatitis [23].

It is mandatory to exclude other causes of AP such as biliary, alcohol-induced, hypercalcemia, and hypertriglyceridemia. The radiological evaluation may show hyperinflation of the balloon, absence of cholelithiasis and biliary duct dilation, compression of the pancreas body, dilation of the pancreatic duct, peripancreatic edema, and free intra-peritoneal fluid [24].

The therapeutic approach consists of the general supportive management measures of AP. Early balloon removal appears to be sufficient to resolve this condition, although conservative treatment without the need for balloon removal has been successfully described in mild cases of AP [24].

Gastric Perforation

The mechanism by which the IGB provokes gastric perforations is not yet understood. It is believed that the device exerts direct contact and constant pressure on the gastric wall, causing ischemia and ulceration of the mucosa [25]. A literature review of 21 cases of gastric perforation caused by the IGB revealed a mortality rate of 14.2% (3 cases) [25].

The treatments varied between conservative, laparotomy, laparoscopy, and combined laparoscopy with endoscopy therapies. This same review [25] described three other perforation cases successfully treated exclusively by endoscopic therapy, demonstrating that this is a viable treatment option in selected cases.

The clinical picture presents itself as an acute abdomen, characterized by the sudden onset of severe abdominal pain with radiation to the left shoulder, hematemesis or melena, and fever. Abdominal palpation may be normal, or it may show signs of acute peritonitis. An abdominal X-ray may reveal pneumoperitoneum, and a CT-scan can demonstrate the presence of a fistula, free fluid in the peritoneal cavity, fluid collections, and compression of the gastric wall (usually the anterior wall) by the ballon.

The initial approach includes the standard treatment of an acute abdomen with clinical management followed by image evaluation. The definitive treatment must take into account the patient’s clinical status, the presence of complications such as fluid collections, and the local expertise of the treatment team. Perforation repair and removal of the device can be performed by a conventional surgical approach (Fig. 8), video laparoscopy, laparoscopy combined with endoscopy, or exclusively by endoscopic therapy [26]. Intravenous antibiotic therapy and admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) are mandatory.

Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome

Although very rare, there are some reports of cases of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome secondary to persistent vomiting and severe malnutrition [27].

Acute vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency can cause Wernicke’s encephalopathy, a lethal condition that requires urgent treatment, characterized by the triad of ataxic gait, encephalopathy, and oculomotor dysfunction (nystagmus and ophthalmoplegia). Its chronicity can lead to Korsakoff’s amnesic syndrome, a neuropsychiatric manifestation of poor prognosis characterized by disorientation and impaired memory (anterograde and retrograde amnesia). The condition is reversible if diagnosed and treated early [28]. It is recommended the daily use of a multivitamin to all patients who undergo any endoscopic and bariatric metabolic therapy (EBMT) to prevent micronutrient deficiencies and regular monitoring of serum nutrient levels 3 months after placement is suggested [29, 30].

Adverse Events Related to the Procedure

Esophageal Laceration and Perforation

Lacerations and perforations typically occur when the device is removed, especially at the gastroesophageal junction, where inflammation and edema can occur during the use of the IGB, and at the upper esophageal sphincter where the lumen narrows increasing the risk of impaction (Fig. 9). Most esophageal perforations are diagnosed during the procedure and, therefore, are amenable to endoscopic treatment with through-the-scope (TTS) clips, over-the-scope clips (OTSC), or fully covered self-expanding metal stents (FCSEMS). Perforations diagnosed early (< 24 h after the procedure) may present a different clinical presentation that varies according to the location of the injury [31].

In cases of perforation of the cervical esophagus, the most common clinical manifestations are dysphagia, subcutaneous emphysema, odynophagia, and dysphonia.

Perforations in the middle esophagus can present chest pain, dyspnea, tachypnea, and subcutaneous emphysema.

In the distal esophagus, the most common features include retrosternal/epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and signs of acute peritonitis. In perforations diagnosed late (> 24 h after the procedure), the patient may present with nonspecific symptoms of mental confusion, hypotension, and sepsis.

A water-soluble contrast-enhanced tomography [31] should be considered the gold standard whenever a perforation is suspected. Treatment depends on the time of diagnosis (intra or post-procedural), perforation characteristics (size, depth, and location of the defect), the presence of intraluminal residues, the patient’s clinical status, the availability of material for defect closure, and the local expertise available.

The approach may be conservative, endoscopic, or surgical. Due to the risk of impaction of the balloon in the cricopharyngeus during its removal, it is recommended that this procedure be performed under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation.

Intragastric Balloon Removal

The removal of the intragastric balloon (IGB) is one of the most critical points in the use of these devices with chances of severe complications when poorly performed (Table 2) [7, 32]. The stiffness of the esophageal sphincters, the state of the device, the lack of ideal materials, or even the inexperience of the endoscopist are predictors of failure [33]. In Video 1, we demonstrate various methods for IGB withdrawal in difficult cases.

(MP4 193012 kb)

A 70-year-old female patient presented for IGB removal 6 months after placement resulting in a total weight loss (TWL) of 20.4% and an excess weight loss (EWL) of 58.8% (Video 1).

In the first endoscopic evaluation, the IGB was impacted in the antrum of the stomach and the conventional technique of puncturing the device followed by the aspiration of all its contents was employed. Afterward, a first attempt was made to remove the IGB with traction using a forceps to remove the balloon. Due to the friability of the balloon, this broke at the cricopharyngeal muscle. This reinforces the recommendation to always perform IGB removal with the patient intubated for safety. A second attempt was made with a large foreign body forceps, which also failed to remove it due to impaction in the same location.

For a third attempt, a polypectomy snare was attached to the outside of the endoscope as an over-the-scope device and a foreign body forceps was used through the endoscope’s working channel. This technique aims to ensure a double grip on the balloon and thus enables a greater traction force. However, this was unsuccessful and the balloon continued to be impacted at the cricopharyngeal muscle.

On the fourth, and final attempt, the IGB was pushed back gently into the stomach under direct endoscopic visualization. The protection valve of the balloon was identiied and with the aid of a snare, the valve was looped and the device was everted carefully, maintaining axial traction towards the mouth while successfully removing it. Post-removal endoscopy revealed no mucosal tear. The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged from the hospital on the same day.

Withdrawal of IGB may surprise even the most experienced endoscopists [34]. It is important to know the various withdrawal techniques and be prepared for challenges while maintaining the patient’s safety.

Conclusion

The intragastric balloon is a safe and effective therapy for weight loss. Although complications are rare and undesirable, they can happen and be serious or fatal. Complications should be suspected in patients who present with persistent or unusual complaints after the adaptive phase.

With respect to contraindications, adherence to dietary and medication guidelines, education, and patient monitoring are essential to prevent and diagnose complications early during IGB use. It is strongly recommended to remove the balloon under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. A thorough inspection of the gastroesophageal mucosa after removing the device is a must to identify complications and treat complications when indicated.

References

Allison DB, Downey M, Atkinson RL, Billington CJ, Bray GA, Eckel RH, et al. Obesity as a disease: a white paper on evidence and arguments commissioned by the council of the obesity society. Obesity. 2008. p. 1161–77.

Espinet-Coll E, Nebreda-Durán J, Gómez-Valero JA, Muñoz-Navas M, Pujol-Gebelli J, Vila-Lolo C, et al. Current endoscopic techniques in the treatment of obesity. Rev. Esp. Enfermedades Dig. 2012. p. 72–87.

Kumar N, Sullivan S, Thompson CC. The role of endoscopic therapy in obesity management: intragastric balloons and aspiration therapy. Diabetes, Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2017;10:311–6.

de Moura EGH, Ribeiro IB, Frazão MSV, et al. EUS-guided intragastric injection of botulinum toxin A in the preoperative treatment of super-obese patients: a randomized clinical trial. Obes Surg. 2019;29:32–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3470-y

Gyring Nieben O, Harboe H. Intragastric balloon as an artificial bezoar for treatment of obesity. Lancet. 1982;319:198–9.

Moura D, Oliveira J, De Moura EGH, et al. Effectiveness of intragastric balloon for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized control trials. Surg Obes Relat Dis [Internet]. 2016;12:420–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26968503

Kotinda APST, de Moura DTH, Ribeiro IB, et al. Efficacy of intragastric balloons for weight loss in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Surg. 2020;30:2743–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04558-5

ASGE Bariatric Endoscopy Task Force and ASGE Technology Committee, Abu Dayyeh BK, Kumar N, et al. ASGE Bariatric Endoscopy Task Force systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting endoscopic bariatric therapies. Gastrointest Endosc [Internet]. 2015;82:425–38.e5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26232362

Lopez-Nava G, Jaruvongvanich V, Storm AC, et al. Personalization of endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies based on physiology: a prospective feasibility study with a single fluid-filled intragastric balloon. Obes Surg [Internet]. 2020;30:3347–53. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32285333

Patel NJ, Gómez V, Steidley DE, et al. Successful use of intragastric balloon therapy as a bridge to heart transplantation. Obes Surg [Internet]. 2020;30:3610–4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32279183

Saber AA, Shoar S, Almadani MW, et al. Efficacy of first-time intragastric balloon in weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Surg [Internet]. 2017;27:277–87. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27465936

Neto MG, Silva LB, Grecco E, et al. Brazilian Intragastric Balloon Consensus Statement (BIBC): practical guidelines based on experience of over 40,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis [Internet]. 2018;14:151–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29108896

Hay D, Ryan G, Somasundaram M, et al. Laparoscopic management of a migrated intragastric balloon causing mechanical small bowel obstruction: a case report and review of the literature. Ann R Coll Surg Engl [Internet]. 2019;101:e172–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31672034

Caruso R, Vicente E, Quijano Y, et al. A combined laparoscopic and endoscopic approach for an early gastric perforation secondary to intragastric balloon: endoscopic and surgical skills with literature review. Obes Surg [Internet]. 2020;30:4103–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32451921

Djelil D, Taihi L, Cattan P. Migration of an intragastric balloon may necessitate enterotomy for extraction. J Visc Surg [Internet]. 2020; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33168475

Koek SA, Hammond J. Gastric outlet obstruction secondary to orbera intragastric balloon. J Surg Case Reports [Internet]. 2018;2018:rjy284. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30386547

Granek RJ, Hii MW, Ward SM. Major gastric haemorrhage after intragastric balloon insertion: case report. Obes Surg [Internet]. 2018;28:281–4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29071537

Kumar N, Bazerbachi F, Rustagi T, et al. The influence of the orbera intragastric balloon filling volumes on weight loss, tolerability, and adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg [Internet]. 2017;27:2272–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28285471

Barola S, Agnihotri A, Chiu AC, et al. Spontaneous hyperinflation of an intragastric balloon 5 months after insertion. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2017;112:412. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28270675

Quarta G, Popov VB. Intragastric balloon hyperinflation secondary to polymicrobial overgrowth associated with proton pump inhibitor use. Gastrointest Endosc [Internet]. 2019;90:311–2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30935931

Barrichello S, de Moura DTH, Hoff AC, et al. Acute pancreatitis due to intragastric balloon hyperinflation (with video). Gastrointest Endosc [Internet]. 2020;91:1207–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31866316

Alsohaibani FI, Alkasab M, Abufarhaneh EH, et al. Acute pancreatitis as a complication of intragastric balloons: a case series. Obes Surg [Internet]. 2019;29:1694–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30826913

Alqabandi O, Almutawa Y, AlTarrah D, et al. Intragastric balloon insertion and pancreatitis: case series. Int J Surg Case Rep [Internet]. 2020;74:263–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32905925

Gore N, Ravindran P, Chan DL, et al. Pancreatitis from intra-gastric balloon insertion: xase report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep [Internet]. 2018;45:79–82. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29579540

Barrichello Junior S, Ribeiro I, Fittipaldi-Fernandez R, et al. Exclusively endoscopic approach to treating gastric perforation caused by an intragastric balloon: case series and literature review. Endosc Int Open. 2018;06:E1322–9. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0743-5520

Perez Aguado G, Cabrera Marrero JC, Jiménez-Ruano L. Combined endoscopy and laparoscopic approach of a gastric perforation due to intragastric balloon insertion. Rev Española Enfermedades Dig [Internet]. 2020; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33228373

Albaugh VL, Williams DB, Aher C V, Spann MD, English WJ. Prevalence of thiamine deficiency is significant in patients undergoing primary bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis [Internet]. 2020; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33478908

Vellante P, Carnevale A, D’Ovidio C. An autopsy case of misdiagnosed Wernicke’s Syndrome after intragastric balloon therapy. Case Rep Gastrointest Med [Internet]. 2018;2018:1–3. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29666718

Shankar P, Boylan M, Sriram K. Micronutrient deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nutrition [Internet]. 2010;26:1031–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20363593

Mechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing bariatric procedures – 2019 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology. Surg Obes Relat Dis [Internet]. 2020;16:175–247. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31917200

Paspatis GA, Arvanitakis M, Dumonceau J-M, et al. Diagnosis and management of iatrogenic endoscopic perforations: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement – Update 2020. Endoscopy [Internet]. 2020;52:792–810. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32781470

Dai S-C, Paley M, Chandrasekhara V. Intragastric balloons: an introduction and removal technique for the endoscopist. Gastrointest Endosc [Internet]. 2015;82:1122. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0016510715025328

Neto G, Campos J, Ferraz A, et al. An alternative approach to intragastric balloon retrieval. Endoscopy [Internet]. 2016;48:E73. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-101856.

Cambi MPC, Baretta GAP, Magro DDO, Boguszewski CL, Ribeiro IB, Jirapinyo P, et al. Multidisciplinary approach for weight regain—how to manage this challenging condition: an expert review. Obes Surg. 2021;31:1290–1303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-05164-1

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ribeiro, IB: acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising the article, final approval. Kotinda, APST: analysis and interpretation of data, revising the article. Sánchez-Luna, SA: revising the English, interpretation of data, editing and drafting article, final approval. Moura, DTH: revising, editing and drafting article, final approval. De Souza, TFS acquisition of data, drafting the article, revising the article, final approval. Mancini, FC: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, final approval; de Matuguma, SE acquisition of data, drafting the article, revising the article, final approval. Rocha, RSP: revising, editing and drafting article, final approval; Luz, GO: revising, editing and drafting article, final approval. Lera dos Santos, ME: revising, editing and drafting article, final approval. Chaves, DM; revising, editing and drafting article, final approval. Franzini, TAP; revising, editing and drafting article, final approval. Sakai, CM; revising, editing and drafting article, final approval. De Moura, ETH: revising, editing and drafting article, final approval: de Moura, EGH analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising the article, final approval

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine Hospital das Clínicas. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Moura reports personal fees from Boston Scientific and personal fees from Olympus, outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key Points

• Intragastric balloon (IGB) is a minimally invasive, reversible, and safe therapy for weight loss.

• Most complications and adverse effects are mild.

• Serious adverse events, when identified early, have a great chance of resolution.

• Endoscopists must be aware of the contraindications and be prepared to effectively treat the adverse effects that may arise during IGB use.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ribeiro, I.B., Kotinda, A.P.S.T., Sánchez-Luna, S.A. et al. Adverse Events and Complications with Intragastric Balloons: a Narrative Review (with Video). OBES SURG 31, 2743–2752 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05352-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05352-7