Abstract

Introduction

The evidence for improved prognostic assessment and long-term survival for extended pancreatoduodenectomy (EPD) compared to standard pancreatoduodenectomy (SPD) in patients with carcinoma of the head of the pancreas has not been considered from only randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Methods

The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the outcomes comparing SPD and EPD in RCTs. Searches were performed on MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane databases using MeSH keyword combinations: ‘pancreatic cancer’, ‘pancreaticoduodenectomy’, ‘extended’, ‘randomized’ and ‘lymphadenectomy’. RCTs published up to 2014 were included. Overall post-operative survival, morbidity, 30-day mortality and length of hospital stay were the outcomes assessed.

Results

Five eligible RCTs with 546 participants were included (EPD = 276 and SPD = 270). EPD was associated with a significantly higher number of excised lymph nodes (LNs) compared to SPD (mean difference = 15.73, 95 % confidence interval (CI) = 9.41–22.04; P < 0.00001; I 2 = 88 %). LN metastasis was detected in 58–68 and 55–70 % of patients who had EPD and SPD, respectively. EPD did not improve overall survival (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.88, 95 % CI = 0.75–1.03; P = 0.11) but did worsen post-operative morbidity compared to SPD (risk ratio (RR) = 1.23; 95 % CI = 1.01–1.50; P = 0.004; I 2 = 9 %). There were no differences in the 30-day mortality (RR = 0.81; 95 % CI = 0.32–2.06; P = 0.66; I 2 = 0 %) or length of hospital stay (mean difference = 1.39, 95 % CI = −2.31 to 5.09; P = 0.46; I 2 = 67 %).

Conclusion

SPD is associated with reduced morbidity, but equivalent long-term benefits compared to patients undergoing EPD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Surgery is the only potential curative option in patients with pancreatic cancer with an overall 5-year survival rate of 20 %.1 Lymph node (LN) involvement is considered one of the most important prognostic indicators,2–6 while the other important factors influencing survival include tumour histology, size, status of resection margins, grade and lymphovascular invasion.7–9 The presence of LN metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reduces a 5-year survival rate from 40 % to less than 10 %.10,11 The ratio of the number of positive and the total number of excised LNs and the presence of capsular invasion are also poor prognostic indicators.12 LN metastases are understood to have a specific pattern of spread with peri-pancreatic nodes generally involving the anterior and posterior peri-pancreatic nodes followed by common hepatic, coeliac and nodes around the superior mesenteric artery before spreading to para-aortic nodes.13 ‘Skip’ metastases, however, are noted in 8 % of patients.14 Perineural tumour invasion has been proposed as a second mechanism of LN metastases.15,16

Considering these patterns of disease progression, it has been postulated that extended lymphadenectomy as a part of pancreaticoduodenectomy (EPD) would provide a better LN clearance and improve prognostic assessment with the ultimate goal of improving long-term patients’ survival.15,17 However, these findings have not been consistently reproduced in the latter published prospective and non-randomized series.18–23 Increased morbidity has been encountered after EPD in retrospective and prospective studies.24 Previous meta-analyses have also both demonstrated no survival differences with EPD.25,26 However, one of these analyses included predominately non-randomized studies (13 out of 16 included studies)25 and the other one26 rather than analyzing time-to-event data which would be the gold standard in reporting survival data, proportion of patients surviving at different time points were considered. Furthermore, another large randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing EPD with SPD has been published.23

Taking together the limitation of previous meta-analyses and the availability of a new study encompassing a significant number of patients, an up-to-date systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted comparing outcomes of patients enrolled in RCTs who underwent SPD and EPD for carcinoma of the head of the pancreas.

Methods

Search Strategy, Eligibility Criteria and Data Extraction

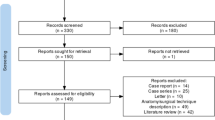

The meta-analysis was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.27 Search was performed on MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane databases using the following MeSH keyword combinations: ‘pancreatic cancer’, ‘pancreaticoduodenectomy’, ‘extended’, ‘randomized’ and ‘lymphadenectomy’. Reference lists of original articles and review articles were considered as additional sources of information. No language or time limit was applied. RCTs comparing EPD versus SPD in patients with head of the pancreas cancer were considered. Considered outcomes were the following: overall survival, number of excised LNs, pathological status of excised LNs, morbidity, 30-day mortality, length of hospital stay, blood loss and duration of surgery. Data were independently extracted by two investigators (B.D. and S.P.) to ensure the homogeneity of data collection and to rule out the effect of subjectivity in data gathering and entry. Disagreements were resolved by iteration, discussion and consensus. To unravel potential systematic biases, the third investigator (R.V.) did a concordance study by independently reviewing all eligible RCTs. Complete concordance was reached for all variables assessed.

Standard and Extended Lymphadenectomy

A standard lymphadenectomy includes dissection of the common hepatic artery from the splenic artery origin to the origins of the hepatic arteries. Perineural tissue and LNs along the common bile duct, station 8 nodes along the hepatic artery, posterior and anterior pancreaticoduodenal nodes and nodes along the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and right lateral wall of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) are removed. Extended lymphadenectomy involves removal of all the LN stations described in standard lymphadenectomy and, in addition, would remove perineural plexus and LNs along the coeliac axis, superior mesenteric artery and para-aortic LNs.

Statistical Analysis

Standard meta-analysis methods28 were applied to evaluate the impact of EPD versus SPD on overall survival times in all patients (primary outcome) overall morbidity, 30-day mortality, in-hospital length of stay, blood transfusion and number of excised lymph nodes (secondary outcomes). We performed sub-group survival analysis in LN-positive and LN-negative patients. Data were analyzed on an intention-to-treat principle, thus including patients who had 30-day post-operative death and minimizing risk of bias. RevMan 5.3.4 was used for data analysis.

Survival (time-to-event) data are best analyzed using hazard ratios

Because time-to-event data necessary to assess the effect of EPD on survival were not reported in the publications describing the RCTs, the hierarchical series of steps as per Parmar et al. was used to extract the hazard ratios (HRs) from the published Kaplan-Meier survival curves.29,30 The overall effect of EPD and SPD on post-operative morbidity and 30-day mortality was calculated by pooling individual log odds ratios (ORs) and risk ratios (RRs) weighted by the inverse of their variances. P values lower than 0.05 were considered significant.

Heterogeneity was considered present when the P value (Cochran’s Q test) was less than 0.1. In addition, inconsistency across studies was quantified by means of I 2 statistic, which is considered significant for values greater than 50 %.

Results

Five randomized trials19–23 comparing EPD and SPD in patients with pancreatic head tumour were published between 1998 and 2014 (Table 1). Overall, 546 participants were enrolled in these trials and randomly assigned to EPD (N = 276, 50.1 %) or SPD (N = 270, 49.9 %). LN metastasis was detected in 58–68 and 55–70 % of patients who had EPD and SPD, respectively. Technical details of extended resection from the included studies are summarized in Table 2.

Primary Outcomes

Overall Survival

All RCTs reported on overall survival, while only two analyzed disease-free survival. Meta-analysis was, therefore, performed to assess the effect of SPD versus EPD on overall survival. None of the included trials found a statistical significant correlation between the extension of pancreatoduodenectomy and patient survival (Fig. 1a). When the studies were considered together, again, no benefit in overall survival was seen following EPD (HR = 0.88, 95 % confidence interval (CI) = 075–1.03; P = 0.11) with no significant heterogeneity (P = 0.92; I 2 = 0 %).

Effect of LN Positivity on Overall Survival

When survival was analyzed by either node-negative or node-positive disease, EPD was not associated with improved survival (HR = 1.07, 95 % CI = 0.76–1.52; P = 0.69, and HR = 1.02, 95 % CI = 0.78–1.33; P = 0.87, respectively). In both cases, there was no statistically significant heterogeneity between the studies (negative LNs: P = 0.45; I 2 = 0 %; positive LNs: P = 0.11; I 2 = 46 %) (Fig. 1b).

Secondary Outcomes

Number of Excised and Positive LNs

Number of excised LNs ranged between 20–40 and 14–17 following EPD and SPD, respectively. EPD was associated with a significantly higher number of excised LNs compared to SPD (mean difference = 15.73, 95 % CI = 9.41–22.04; P < 0.00001). However, there was significant heterogeneity between the studies (P < 0.00001; I 2 = 88 %) (Fig. 2a).

Interestingly, the higher LN yield in the EPD group was not translated into a greater proportion of patients with LN metastasis. The meta-analysis did not find a greater proportion of LN metastasis in patients who had EPD (OR = 0.78, 95 % CI = 0.55–1.10; P = 0.16) (P = 0.85; I 2 = 0 %) (Fig. 2b).

Overall Post-operative Morbidity

The post-operative morbidities considered in the included in the studies are shown in Table 3. When considered together, EPD was associated with a greater risk of post-operative morbidity compared to SPD (RR = 1.23; 95 % CI = 1.01–1.50; P = 0.004) (Fig. 3). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity between the studies (P = 0.35; I 2 = 9 %). When each complication (pancreatic leak, bile leak, intra-abdominal abscess/collection, delayed gastric empting, cholangitis, wound infections, lymphocele) was considered individually, meta-analysis failed to identify a significant difference between the two groups.

Thirty-Day Post-operative Mortality

Despite the higher incidence of post-operative complications, there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality between patients treated with EPD versus SPD (RR = 0.81; 95 % CI = 0.32–2.06; P = 0.66). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity (P = 0.56; I 2 = 0 %).

Duration of Surgery

Duration of surgery was significantly longer for patients who had EPD compared to SPD (mean difference = 0.72, 95 % CI = 0.24–1.21; P = 0.004). However, there was significant heterogeneity between the included studies (P = 0.03; I 2 = 67 %).

Need of Blood Transfusion

The need for blood transfusion was not different between EPD and SPD groups (mean difference = 0.12, 95 % CI = −0.05 to 0.34; P = 0.17) with no significant heterogeneity detected (P = 0.72; I 2 = 0 %).

Length of Hospital Stay

Length of stay in hospital was similar when EPD was compared to SPD (mean difference = 1.39, 95 % CI = −2.31 to 5.09; P = 0.46), although there was significant heterogeneity (P = 0.03; I 2 = 67 %).

Discussion

Lymphadenectomy plays an important role in cancer surgery to remove LN metastases and identifies patients who may benefit from adjuvant treatments.31–33 However, the role of extended resections to provide curative intent when considering pancreatic cancer has been much debated. This is because of the poor outcomes associated with this type of cancer and the poor chemosensitivity of these tumours. Some surgeons have a pragmatic approach regarding ‘aggressive’ surgical options such as extended lymphadenectomy with a view to improve patients’ long-term survival. This is partly driven by the knowledge that LN metastases are common and adversely affect survival and that adjuvant chemo/chemoradiotherapy offers marginal benefits to survival following surgery.34–36

However, the rationale supporting EPD must be put into context of available evidence to support this practice as being oncologically sound and safe. SPD is associated with significant peri-operative morbidity and mortality.37 EPD is associated with greater morbidity.21,38,39 In addition, five RCTs have failed to demonstrate any survival benefit for EPD and the results on morbidity remain controversial. Our meta-analysis of only RCTs shows that EPD is not associated with significantly greater survival but is associated with increased morbidity. The results of previously published meta-analyses are similar, but limited by methodological issues.25,26 They considered both RCTs and non-randomized studies, thus lowering the level of evidence by increasing the risk of bias. Moreover, these meta-analyses did not use the hazard ratio for conducting their analyses, which is the optimal effect measure for time-to-event data as the case of survival analysis. These studies reported risk ratios or differences in median survival. It is well known that these measures can achieve misleading results, as they do not fully account for the correlation between death and time. In fact, combining the number of events reported at specific time points for each trial as relative risks can be difficult to interpret particularly because individual trials did not contribute data at the same time points. Moreover, bias arises as time points are subjectively chosen by the reviewers or selectively reported in the trials.30 For instance, among the studies included in this meta-analysis, one reported survival up to 2 years,20 two studies finished their observation before 5 years,19,23 and two reported 5-year survival.21,22 Inspite of this heterogeneity, Xu et al.26 included 3 and 5 years survival rates in their meta-analysis even though some studies did not reach it.

This meta-analysis also investigated the number of excised LNs and their pathological status. The number of LNs retrieved in the EPD group was significantly higher (mean difference, n = 16) than those in the SPD group. However, this did not translate into a higher number of positive LNs in the EPD group or, more importantly, any survival benefit. When patients with or without node metastases were considered separately, a lack of significant difference remained. This is in keeping with the data from four of five RCTs.20–23

Another important issue for pancreatoduodenectomy is morbidity. Delayed gastric emptying, diarrhoea and malnutrition are common following EPD due to the denervation of coeliac plexus and the plexus around SMA. This meta-analysis showed a significantly higher risk of complications for patients who had EPD compared to SPD (121/276, 44 % vs. 99/270, 36 %). These are worse after a 360° dissection of the nerve plexus around the coeliac axis and SMA.21,22 Reduced incidence and severity of these complications can be achieved by limiting dissection to 180° circumference of these vessels.23 The higher rate of complications following EPD reported in this meta-analysis is probably underestimated because RCTs are generally designed to look at the treatment main effect, which here is patient survival, rather than complication rate. Therefore, it may be that the true relative risk of complications for patients undergoing EPD compared to SPD would be greater than the 23 % reported.

While the present meta-analysis has addressed the statistical limitations of the previous meta-analyses in this most up-to-date review, some of the included RCTs comprise small patient cohorts. In addition, there is variability in the extent of lymphadenectomy and nerve plexus resection in the included RCTs with a higher number of patients in the Japanese cohort having more LNs harvested than those in the Western cohort. In addition, none of the studies have addressed the role of EPD in locally advanced disease.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis of RCTs demonstrated that SPD is associated with reduced morbidity and equivalent long-term benefits to patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma compared to EPD and should be preferred to EPD.

References

Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, Bassi C, Dunn JA, Hickey H, Beger H, Fernandez-Cruz L, Dervenis C, Lacaine F, Falconi M, Pederzoli P, Pap A, Spooner D, Kerr DJ, Büchler MW ; European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1200–10.

Bogoevski D, Yekebas EF, Schurr P, Kaifi JT, Kutup A, Erbersdobler A, Pantel K, Izbicki JR. Mode of spread in the early phase of lymphatic metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: prognostic significance of nodal microinvolvement. Ann Surg. 2004;240:993–1000.

Mosca F, Giulianotti PC, Balestracci T, Di Candio G, Pietrabissa A, Sbrana F, Rossi G. Long-term survival in pancreatic cancer: pylorus-preserving versus Whipple pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery. 1997;122:553–66.

Trede M, Schwall G, Saeger HD. Survival after pancreatoduodenectomy. 118 consecutive resections without an operative mortality. Ann Surg. 1990;211:447–58.

Geer RJ, Brennan MF. Prognostic indicators for survival after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 1993;165:68–72.

Nitecki SS, Sarr MG, Colby T V, van Heerden JA. Long-term survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Is it really improving? Ann Surg. 1995;221:59–66.

Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Arnold MA, Chang DC, Coleman J, Hodgin MB, Sauter PK, Hruban RH, Riall TS, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: A single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1199–210.

Kazanjian KK, Hines OJ, Duffy JP, Yoon DY, Cortina G, Reber HA. Improved survival following pancreaticoduodenectomy to treat adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: the influence of operative blood loss. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1166–71.

Wagner M, Redaelli C, Lietz M, Seiler CA, Friess H, Büchler MW. Curative resection is the single most important factor determining outcome in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2004;91:586–94.

Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hayashidani Y, Hashimoto Y, Nakashima A, Yuasa Y, Kondo N, Ohge H, Sueda T. Number of metastatic lymph nodes, but not lymph node ratio, is an independent prognostic factor after resection of pancreatic carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:196–204.

Zacharias T, Jaeck D, Oussoultzoglou E, Neuville A, Bachellier P. Impact of lymph node involvement on long-term survival after R0 pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:350–6.

Wind J, Lagarde SM, Ten Kate FJ, Ubbink DT, Bemelman WA, van Lanschot JJ. A systematic review on the significance of extracapsular lymph node involvement in gastrointestinal malignancies. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:401–8.

Michalski CW, Kleeff J, Wente MN, Diener MK, Büchler MW, Friess H. Systematic review and meta-analysis of standard and extended lymphadenectomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2007;94:265–73.

Durczyński A, Hogendorf P, Szymański D, Grzelak P, Strzelczyk J. Sentinel lymph node mapping in tumors of the pancreatic body: preliminary report. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2012;16:206–9.

Ishikawa O, Ohhigashi H, Sasaki Y, Kabuto T, Fukuda I, Furukawa H, Imaoka S, Iwanaga T. Practical usefulness of lymphatic and connective tissue clearance for the carcinoma of the pancreas head. Ann Surg. 1988;208:215–20.

Hirai I, Kimura W, Ozawa K, Kudo S, Suto K, Kuzu H, Fuse A. Perineural invasion in pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2002;24:15–25.

Manabe T, Ohshio G, Baba N, Miyashita T, Asano N, Tamura K, Yamaki K, Nonaka A, Tobe T. Radical pancreatectomy for ductal cell carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Cancer. 1989;64:1132–7.

Henne-Bruns D, Vogel I, Lüttges J, Klöppel G, Kremer B.. Ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas head: survival after regional versus extended lymphadenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 45:855–66.

Pedrazzoli S, DiCarlo V, Dionigi R, Mosca F, Pederzoli P, Pasquali C, Klöppel G, Dhaene K, Michelassi F. Standard versus extended lymphadenectomy associated with pancreatoduodenectomy in the surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Lymphadenectomy Study Group. Ann Surg. 1998;228:508–17.

Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Sohn TA, Campbell KA, Sauter PK, Coleman JA, Abrams RA, Hruban RH. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without distal gastrectomy and extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma, part 2: randomized controlled trial evaluating survival, morbidity, and mortality. Ann Surg. 2002;236:355–66.

Nimura Y, Nagino M, Takao S, Takada T, Miyazaki K, Kawarada Y, Miyagawa S, Yamaguchi A, Ishiyama S, Takeda Y, Sakoda K, Kinoshita T, Yasui K, Shimada H, Katoh H. Standard versus extended lymphadenectomy in radical pancreatoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: long-term results of a Japanese multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:230–41.

Farnell MB, Pearson RK, Sarr MG, DiMagno EP, Burgart LJ, Dahl TR, Foster N, Sargent DJ. A prospective randomized trial comparing standard pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatoduodenectomy with extended lymphadenectomy in resectable pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Surgery. 2005;138:618–28.

Jang JY, Kang MJ, Heo JS, Choi SH, Choi DW, Park SJ, Han SS, Yoon DS, Yu HC, Kang KJ, Kim SG, Kim SW. A prospective randomized controlled study comparing outcomes of standard resection and extended resection, including dissection of the nerve plexus and various lymph nodes, in patients with pancreatic head cancer. Ann Surg. 2014;259:656–64.

Pedrazzoli S, Pasquali C, Sperti C. Extent of lymphadenectomy in the resection of pancreatic cancer. Analysis of the existing evidence. Rocz Akad Med w Białymstoku. 2005;50:85–90.

Iqbal N, Lovegrove RE, Tilney HS, Abraham AT, Bhattacharya S, Tekkis PP, Kocher HM. A comparison of pancreaticoduodenectomy with extended pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of 1909 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:79–86.

Xu X, Zhang H, Zhou P, Chen L. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of pancreatoduodenectomy with extended lymphadenectomy in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:311.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Higgins JPT GS. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 501. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815–34.

Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16.a

Glimelius B, Dahl O, Cedermark B, Jakobsen A, Bentzen SM, Starkhammar H, Grönberg H, Hultborn R, Albertsson M, Påhlman L, Tveit KM; Nordic Gastrointestinal Tumour Adjuvant Therapy Group. Adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer: a joint analysis of randomised trials by the Nordic Gastrointestinal Tumour Adjuvant Therapy Group. Acta Oncol. 2005;44:904–12.

Morris EJA, Maughan NJ, Forman D, Quirke P. Who to treat with adjuvant therapy in Dukes B/stage II colorectal cancer? The need for high quality pathology. Gut. 2007;56:1419–25.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer—30 Years Later—NEJM [Internet]. [cited 2014 Dec 1]. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMe068204

Neoptolemos JP, Dunn JA, Stocken DD, Almond J, Link K, Beger H, Bassi C, Falconi M, Pederzoli P, Dervenis C, Fernandez-Cruz L, Lacaine F, Pap A, Spooner D, Kerr DJ, Friess H, Büchler MW; European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:1576–85.

Sultana A, Neoptolemos J, Ghaneh P. Adjuvant treatment. HPB (Oxford). 2006;8:352–64.

Neoptolemos J, Buchler M, Stocken DD, Ghaneh P, Smith D, Bassi C, Moore M, Cunningham D, Dervenis C, Goldstein D. ESPAC-3(v2): A multicenter, international, open-label, randomized, controlled phase III trial of adjuvant 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid (5-FU/FA) versus gemcitabine (GEM) in patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. ASCO Meet Abstr. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2009;27(18S):LBA4505.

de Wilde, RF, Besselink MGH, van der Tweel I, de Hingh IHJT, van Eijck CHJ, Dejong CHC, Porte RJ, Gouma DJ, Busch ORC, Molenaar IQ and for the Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group. Impact of nationwide centralization of pancreaticoduodenectomy on hospital mortality. Br J Surg. 2012;99:404–10.

Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Coleman JA, Sauter PK, Hruban RH, Pitt HA, Lillemoe KD. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma: comparison of morbidity and mortality and short-term outcome. Ann Surg. 1999;229:613–22.

Farnell MB, Aranha G V, Nimura Y, Michelassi F. The role of extended lymphadenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: strength of the evidence. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:651–6.

Funding sources

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Synopsis

Standard lymphadenectomy is associated with reduced morbidity, but equivalent long-term benefits compared to patients undergoing extended lymphadenectomy in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy for head of the pancreas cancer.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dasari, B.V., Pasquali, S., Vohra, R.S. et al. Extended Versus Standard Lymphadenectomy for Pancreatic Head Cancer: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Gastrointest Surg 19, 1725–1732 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-015-2859-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-015-2859-3