Abstract

This study investigates the impact of religiousness on mental health indicators in a population sample of Israeli Jews aged 50 or older. Data are from the Israel sample of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE-Israel), collected from 2005 to 2006. Of the 1,287 Jewish respondents, 473 (36.8 %) were native-born Israelis and 814 (63.2 %) were diaspora-born. Religious measures included past-month synagogue activities, current prayer, and having received a religious education. Mental health outcomes included single-item measures of lifetime depression and life satisfaction, along with the CES-D and EURO-D depression scales, the CASP-12 quality of life scale, and the LOT-R optimism scale. Participation in synagogue activities was found to be significantly associated with less depression, better quality of life, and more optimism, even after adjusting for effects of the other religious measures, for sociodemographic covariates, for the possibly confounding effect of age-related activity limitation, and for nativity. Findings for prayer were less consistent, including inverse associations with mental health, perhaps reflecting prayer’s use as a coping response. Finally, religious education was associated with greater optimism. These results underscore a modest contribution of religious participation to well-being among middle-aged and older adults, extending this research to the Israeli and Jewish populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Research on religious correlates or determinants of mental-health-related outcomes has become an increasingly popular topic of investigation over the past several years. Empirical studies actually date back many decades, and more scholarly writing has accumulated on the subject than most people, including active researchers, may realize. A bibliography entitled Religion and Mental Health, published by the National Institute of Mental Health in 1980, contained over 1,800 entries (Summerlin 1980). Since that time, more programmatic research has flourished, including hundreds of sophisticated population-based, clinical, behavioral, and social research studies on a wide range of psychiatric and psychological outcomes (see Koenig et al. 2012; Levin 2010).

While consistent findings have begun to emerge, as well as a general acknowledgment that religious expression influences human well-being across different stages of the natural history of disease, there is much that we still do not know, including some very fundamental information. Much of this lacuna results from what might be termed the monochromatic nature of so much of this research: studies of North American members of Christian denominations, mostly White, mostly based on non-probability samples, and mostly providing minimally controlled analyses of a respective outcome variable, often a single-item measure. This is not just the conclusion of the present author. Comprehensive reviews continue to underscore these points, including an expert summary of three decades of research on religion and well-being that identified a “need for more rigorous methodologies, broader samples, greater precision in measuring types of religiosity, and measures that differentiate the major components of [subjective well-being]” (Diener et al. 1999, p. 289).

Relatively fewer studies have investigated other religious groups, and Jews have fared especially poorly. This is ironic, as one of the earliest empirical studies of note was an analysis of data on mental health status and treatment among Jewish patients from the Midtown Manhattan Study, contained in the classic book Mental Health in the Metropolis, published 50 years ago (Srole and Langner 1962). Since that time, the religion and mental health field has continued to suffer from a relative lack of empirical studies (a) of Judaism or religiously Jewish subjects; (b) of populations outside the U.S.; (c) that examine a wider range of outcomes—psychiatric, psychosocial, or psychological; and (d) that utilize data from large national probability-based population surveys. The present study is an effort to check all of these boxes and to contribute to a more systematic, population-based approach to the study of religion and mental health among Jews.

1.1 Judaism and Mental Health

The best and most systematic research on the mental health of Jews conducted to date is a recent and ongoing series of studies by Rosmarin and associates (e.g., Pirutinsky et al. 2011; Rosmarin et al. 2009a, b, c, d, 2010, 2011). These analyses show, consistently and clearly and in relation to various mental health outcomes, that more religiously observant Jews tend to report lower scores on psychiatric symptom indices, such as for depression and anxiety, and to do better according to psychosocial measures and indicators of well-being. These studies have been conducted in the U.S. and have drawn heavily on subjects from across the spectrum of Orthodox Judaism and from communities on the east coast. By design, they are mostly smaller psychological studies and use a mix of methods, drawing on clinical, community-based, and recruited samples. Accordingly, this research is not national in scope nor does it draw on probability samples, and thus is not intended to provide population-based estimates.

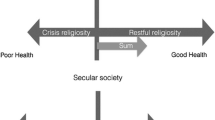

An equivalent body of systematic research among Israeli Jews does not exist, although several studies have shed light on focused aspects of a religion-mental-health relationship in this religious community. Religiousness, variously assessed, has been found to exhibit a significant protective effect against psychological distress (Anson et al. 1990) and to be associated with greater life satisfaction (Amit 2010; Levin 2011b). Those few studies that have stratified by categories of Jewish identity or observance have tended to find better mental health or well-being among more religiously observant subjects or respondents (Anson et al. 1991; Kark et al. 1996; Landau et al. 1998; Levav et al. 2008; Shkolnik et al. 2001; Shmotkin 1990; Shmueli 2006; Vilchinsky and Kravetz 2005), echoing the U.S. studies by Rosmarin and colleagues. Brand new findings from the Israeli sample of the Gallup World Poll (Levin 2011c) have even identified something of a gradient in well-being as one moves “rightward” from hiloni (secular) to masorti (traditional) to dati (religious) to haredi (Orthodox) Jews, categories with special meaning in Israel. Interestingly, a similar gradient among U.S. Jews was also identified for physical health, according to self-report measures of overall and functional health, across the familiar American categories of denominational affiliation (i.e., secular, Reform, Reconstructionist, Conservative, and Orthodox) (Levin 2011a).

A distinguishing feature of Israeli Jewish experience is the presence of distinct populations differentiated by nativity—i.e., place of birth. Native-born and diaspora-born Israelis are distinct not just culturally and socioeconomically, but also religiously. The cultural and national origins of Jews making aliyah (immigrating) to Israel have undergone some shifts over the decades, so the distinction here is not a simple one, such as between Ashkenazim (European Jews) and Sephardim (Jews of Middle Eastern, North African, or Asian ancestry). Substantial immigrant populations have come from the former Soviet Union, from Ethiopia, and from elsewhere, and each brings its own norms and religious traditions (or lack thereof), each confronts its own distinct challenges of adaptation to life in Israel (Lomsky-Feder and Rapoport 2001), and each presents with a different mental health symptom profile and set of psychosocial needs (e.g., Ponizovsky et al. 1998).

Recent studies have begun to examine the mental health status and needs of immigrants to Israel, and significant differences in selected outcomes have been identified, differences due in part to recency and origin of migration and to one’s level of religiosity (Amit 2010). A small body of psychiatric-epidemiologic findings has accrued, pointing to generally higher levels of psychological distress and a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders among immigrants, depending upon the nation of origin and other factors such as availability of social and family support and length of residence (see Mirsky 2009).

What this all means, precisely, for statistical associations between respective religious and mental-health-related measures in the Israeli Jewish population is less clear. It does, though, encourage taking into account the nativity status of respondents, for example through adjusting for effects of whether one is a native-born Israeli or is diaspora-born (i.e., an immigrant). Such a simple dichotomous construct may mask considerable diversity and capture at best a gemish (mix) of many other influences, but, if included in a respective dataset, even a binary nativity variable enables a statistical control for something that may be responsible for substantial variation in religious expression, mental health, or both, as well as in certain sociodemographic characteristics. To fail to account for such a factor, then, could lead to inaccurate findings.

1.2 Conceptual and Theoretical Issues

Previous research has identified different patterns of religious correlates or determinants of different mental health or well-being indicators over different time-referents in different populations. But it is not a simple matter to reduce these results to a basic set of normative findings or expectations; there is just too much inconsistency and too many findings to consider. For example, a multi-wave, national probability study of African Americans found that a wide range of religious measures exhibited contemporaneous effects on selected indicators of well-being and mental health, but longitudinal effects on only a few, and these were diminished after controlling for lagged (baseline) effects and sociodemographic covariates (Levin and Taylor 1998). Where significant longitudinal findings have emerged, moreover, religion has been found in some studies to exhibit a buffering rather than primary-preventive effect (e.g., Williams et al. 1991). In an important review of nearly 150 depression studies, the authors asked researchers also to consider the possibility of bidirectional causal effects—i.e., that religiousness may prevent depression, that depression may suppress religious practice, and/or that both are influenced by additional common factors (Smith et al. 2003). Not to belabor the point, but the relationship between religion, broadly defined, and mental and emotional well-being, also broadly defined, is complicated and not reducible to a single soundbite.

Recent findings from the World Values Survey demonstrate this point among Jews, both in Israel and in a multinational diaspora subsample. Among Israeli Jews, affirming the importance of God in one’s life was modestly associated with greater life satisfaction, but not with happiness. In the diaspora, the same measure was associated with greater happiness, as was more frequent attendance at synagogue services, but neither was associated with life satisfaction (Levin 2011b). It could be that religion relates in one way to measures of affect or emotional state (e.g., happiness), in another way to cognitive assessments such as of congruence (e.g., life satisfaction), and in still another way to psychiatric outcomes such as mood disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety), and that this pattern of associations itself varies across cultures or religions.

The present study, which contains three religious measures and multiple single-item and scaled measures of mental health and psychological well-being (see Sect. 2.2, below), provides an opportunity to examine these linkages more closely in a sample of Israeli Jews. Religious measures include assessments of synagogue participation over the past month, the frequency of current prayer, and having received a religious education as a youth. Each of these is hypothesized to relate significantly to the study’s outcome indicators, but for somewhat distinctive reasons (that cannot necessarily be deduced from the present data).

It is theorized that the synagogue variable will be associated with better mental health. This may be due to the benefits of tangibly and emotionally supportive religious fellowship. Participation in the life of a religious congregation can benefit well-being in this way for several reasons. For example, congregations and fellow congregants can provide help during times of challenge, fellow worshipers may represent significant companion friends, and one’s congregation may be a source of other formal and informal social relationships (see Krause 2008). Each of these added benefits of regular religious attendance may be salutary for one’s mental health for reasons that go beyond a specifically spiritual impact.

It is expected that frequent prayer will be inversely associated with mental health. This may be due to its use as a religious coping mechanism in response to general and specific life challenges, including mental health challenges. Religion in general, and prayer in particular, can function as a coping mechanism in several ways. For example, prayer can help to reconstruct one’s appraisal of a challenging situation, it can imbue significance and meaning onto otherwise random or confusing troubles, if it can foster perseverance, it can connect one to a transcendent source of support, it can motivate one with a renewed sense of purpose, and it can ameliorate feelings of anger and enhance feelings of peace (Pargament 1997). If so, then higher levels of psychological distress may induce greater prayerfulness; thus, the possibility of a negative association between the two constructs.

Specifying an impact of religious education on mental health is more difficult. Childhood religious education, ideally, instills a worldview that encourages reliance on God and integration into a religious community, both of which may promote psychological well-being and ostensibly exhibit a primary-preventive function in relation to mental health, as one moves forward in life. Or it may socialize one to value religion as a lifelong coping resource that is drawn on in times of physical or emotional challenge. Religious education may also be interrelated with and exogenous to the other two religious measures in this study—that is, a force for religious formation that shapes one’s subsequent participation in synagogue life and predisposes one to rely on prayer, at least on average moreso than those who did not receive such an education. Thus, in a multivariable setting, it is hard to predict whether having received a religious education will be positively or inversely associated with well-being, whether this will depend upon the outcome, and whether it will withstand adjusting for other variables with which it may covary, such as age (as in a cohort effect), secular education (which it may substitute for in some very religious communities), and nativity (such that religious education may be less prevalent, on average, in mostly secular Israel).

The first two religious indicators especially may reflect one’s ongoing state of physical or functional health. This study contained several measures of physical health status, including a single-item measure of activity limitation over the past 6 months; its effects were adjusted for in the present analyses, as is standard in analyses of psychological well-being. As this is a prevalence study (or in the language of social research, a cross-sectional survey), there is thus added complexity in interpreting associations between (religious) exposure variables and mental health outcomes. The wording and time-referents of respective measures can help us to infer temporal sequence, in some instances, where it would not otherwise be possible due to limitations of study design. Accordingly, putative effects of the these two religious variables may be more or less tricky to interpret with this set of outcomes in this study, as synagogue activities are assessed over the past month, prayer is assessed in the present, and the mental health measures are assessed over various time frames. It is thus important to be cautious not to overinterpret statistically significant associations as evidence of risk or protection, epidemiologically speaking, without first trying to reason through the implied temporality and directionality of respective findings.

2 Methods

2.1 The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE)

The SHARE is a cross-national and multidisciplinary resource containing individual-level data on health, socioeconomic status, and social and family networks among adults aged 50 and over, based on the Health and Retirement Study and the English Longitudinal Study of Aging. The first wave of the SHARE was conducted in 2004, in 11 European nations, and totaled over 27,000 respondents (Börsch-Supan et al. 2005). Subsequently, three waves of data collection have now been completed, with additional national samples added and a total of over 45,000 respondents.

An Israeli sample was added to the SHARE database, with data collected from October, 2005, through July, 2006 (Litwin 2009). Multi-stage stratified area probability sampling of households was used, drawing on a nationwide telephone directory database (with 95 % population coverage) and a sample of 150 of Israel’s official 2,300 statistical areas. The sample of eligible households was 2,586, and the total sample of household interviews was 1,771. This gave a response rate of 68.5 %, higher than for all but one of the European samples. The final sample size for SHARE-Israel contained 2,586 interviewed respondents, of which 2,498 were aged 50 or older. Data were collected through a computer assisted personal interview (CAPI) system, with interviews lasting about 90 min. More detailed information on the study’s design, sampling, and data collection procedures can be found elsewhere (Litwin and Sapir 2008). A significant focus of the SHARE-Israel study, since its onset, has been on epidemiologic investigation of patterns and determinants of mental health and well-being outcomes (e.g., Achdut and Litwin 2008; Amit and Litwin 2010; Ayalon et al. 2010; Roll and Litwin 2010; Shmotkin and Litwin 2009).

2.2 Measures

The present analyses of data from the SHARE study’s Israeli sample utilize single-item variables and scales assessing religiousness, mental health, and sociodemographic characteristics and other covariates. Many of these were reverse-coded or contain other recodes in order to facilitate analyses. These analyses were conducted using the sample’s 1,287 Jewish respondents (identified through a single-item religious affiliation measure), representing 49.8 % of the overall Israeli sample.

2.2.1 Religious Indicators

Religious measures include synagogue activities (“Have you done any of these activities in the last month?: Taken part in a religious organization (church, synagogue, mosque, etc.)”; (coded: 0 = no, 1 = yes); prayer (“Thinking about the present, how often do you pray?”; coded: 1 = never, 2 = less than once a week, 3 = once a week, 4 = a couple of times a week, 5 = once daily or almost daily, 6 = more than once a day); and religious education (“Have you been educated religiously by your parents?”; coded: 0 = no, 1 = yes).

2.2.2 Mental Health Outcomes

Mental health measures include ever depressed (“Has there been a time or times in your life when you suffered from symptoms of depression which lasted at least 2 weeks?”; coded: 0 = no, 1 = yes); life satisfaction (“How satisfied are you with your life in general?”; coded: 1 = very dissatisfied, 2 = somewhat dissatisfied, 3 = somewhat satisfied, 4 = very satisfied); a version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale amended with three items from the Health and Retirement Survey (a summary index of 14 items [coded: 1 = almost none of the time, 2 = some of the time, 3 = most of the time, 4 = almost all of the time] assessing depressive affect, positive affect, somatic symptoms, and interpersonal relations over the past week [α = .89]); the EURO-D Depression Scale (a summary index of 12 binary items [all recoded: 0 = no, 1 = yes] assessing affective suffering and lack of motivation mostly over the past month [α = .74]); the CASP-12 Quality of Life Scale (a summary index of 12 items [coded: 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often] offering current assessment of control, autonomy, self-realization, and pleasure [α = .81]); and the Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) Scale (a summary index of seven items [coded: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree) assessing current optimism [α = .77]). The EURO-D is of recent vintage, developed for multinational European surveys like the SHARE (Castro-Costa et al. 2007, 2008; Prince et al. 1999); the CASP (Higgs et al. 2003; Hyde et al. 2003), the LOT (Andersson 1996), and especially the CES-D (Radloff 1977) have been more widely used.

2.2.3 Covariates

Sociodemographic measures include age (in years), sex (0 = male, 1 = female), education (0 = none, 1 = elementary school, 2 = non-academic secondary school—did not graduate, 3 = non-academic secondary school—graduated, 4 = academic secondary school—did not graduate, 5 = academic secondary school—graduated), and marital status (0 = not currently married and living together, 1 = currently married and living together). Other covariates used in these analyses include activity limitation (“For the past 6 months at least, to what extent have you been limited because of a health problem in activities people usually do?”; coded: 1 = not limited, 2 = limited, but not severely, 3 = severely limited) and nativity (0 = born outside Israel, 1 = born in Israel).

2.3 Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) and bivariate Pearson (r) correlations for all study variables were obtained using the UNIVARIATE and CORR procedures, respectively. A strategy of hierarchical OLS regression was used to model each of the six mental health indicators, separately, onto the study variables. In Model I, each mental health indicator was regressed onto the three religious variables; in Model II, the four sociodemographic variables plus activity limitation were added; and in Model III, nativity was added. These analyses were conducted using the REG procedure. Both standardized (β) and unstandardized (b) regression coefficients are reported, in order to enable comparison of associations both within and among respective mental health indicators and associated models.

This strategy provides an opportunity to examine each religious variable’s putative impact on several mental health outcomes in multiple situations: first, bivariately (via correlations); second, multivariably in the presence of the other two respective religious variables (Model I); and, third, multivariably after hierarchically controlling for covariates (Models II and III). Given the inherent limitations of the prevalence study design, this approach offers the fullest possible look at the associations between religious exposures and mental health outcomes in these data at the present time—until a second wave of data are collected from the SHARE’s Israeli sample and longitudinal models can be tested.

3 Results

In Table 1, bivariate associations are presented for all study variables. A few notable findings stand out. The three religious measures are strongly and significantly intercorrelated; likewise, the six mental health measures. Activity limitation is a strong, significant correlate of all six outcome measures (such that greater limitation is associated with poorer mental health). Active synagogue-goers are more optimistic (according to the LOT-R), but they are not significantly inclined, bivariately, with respect to any other mental health measure. Having received a religious education in childhood is associated with less life satisfaction and more depression (CES-D and EURO-D). One’s current level of prayer is associated with greater depression (CES-D and EURO-D) and a lower quality of life (CASP-12). As this measure assesses current praying, it may be that its responses reflect one’s mental health status rather than antecede it. Each of the sociodemographic variables is significantly associated with some combination of religious and mental health measures. Finally, native-born Israelis are both significantly less religious (according to all three religious measures) and in significantly better mental health (according to all six mental health measures). They also exhibit significantly less activity limitation and are significantly younger, more educated, and more likely to be married. These latter findings support the decision to adjust for nativity in analyses seeking to characterize the relationship between religiousness and mental health in this population.

In Table 2, results are presented for hierarchical OLS regressions for each mental health indicator. Net religious effects are not observed for the single-item indicators (ever depressed and life satisfaction). But statistically significant, and in some instances substantial, religious effects are observed with respect to the four mental health scales; for three of these the effects persist through Model III.

Past-month participation in synagogue activities is associated with less depression according to the CES-D (β = −.09, p < .01) and with better quality of life (β = .08, p < .05) and more optimism (β = .10, p < .01), all after adjusting for effects of the other religious measures, the sociodemographic covariates, activity limitation, and nativity, most of which exhibited significant net effects on the respective outcome. By contrast, current prayer is associated with more depression according to the CES-D (β = .12, p < .001) and with poorer quality of life (β = −.10, p < .01) and less optimism (β = −.08, p < .05), again after adjusting for effects of all other study variables. Having received a religious education has a few gross effects, but these do not persist after adjusting for the nativity or the other covariates, except for one: a significant net association with optimism (β = .08, p < .01).

As indicated in Model III results, even with all other study variables included, native-born Israelis exhibit greater life satisfaction, less depression, better quality of life, and more optimism. Yet adjusting for effects of nativity, as well as of activity limitation and age, plus the other two religious measures and the other covariates, did not explain away the significant salutary effects of recent synagogue participation. The apparently protective effect of going to synagogue does not then appear to be a result of the possible confounding of declines in such participation as a result of declining functional health or increasing age. Indeed, in the present sample, according to Table 1, there are no significant zero-order associations between synagogue activities and these two variables. Nor is this finding attributable to effects of nativity on these or other measures.

4 Discussion

To summarize, synagogue participation is modestly but positively associated with mental health, according to several outcome measures, and these effects persist even after adjusting for age, activity limitation, nativity, and the other study variables. Prayer was associated with poorer mental health, likewise, but its current time-referent raises the possibility that it reflects a challenging mental health state rather than represents an actual risk factor for psychological distress. Finally, those who received a religious education in childhood were significantly more optimistic.

The main take-home point here is that these findings underscore a modest contribution of religious fellowship to psychological well-being among middle-aged and older adults, and extend this research to the Israeli and Jewish populations. Findings for the other religious measures were inconsistent or ambiguous, perhaps reflecting features of their measurement (i.e., current as opposed to lifelong prayer) or absence of a meaningful theoretical rationale for a positive protective effect on, for example, depressive symptoms (e.g., in re: childhood religious education decades earlier). The findings for synagogue activities, by contrast, are robust: they manifest across outcome measures and withstand controlling for several potentially exogenous, mediating, or confounding influences.

Interpretation of these findings is limited by the prevalence-study design. This is a standard caveat of any psychiatric-epidemiologic analysis based on cross-sectional survey data. However, the wording of some of the study’s questions—synagogue activities over the past month, current prayer, religious education in childhood, depression over the past week or past month, current quality of life and optimism, etc.—does enable a guarded if imprecise inference of temporality. But it is important not to overstate this ability or overinterpret these results; these remain cross-sectional findings.

Additionally, the three religious variables were modeled together, rather than having been run as separate sets of analyses. This strategy may have masked additional positive findings that would have emerged if the religious variables were modeled separately. The latter approach was decided against because such a decision would have tripled the amount of analyses, increasing the likelihood of chance findings, and, more importantly, it is more realistic to consider these variables together as they function together in the lives of the respondents being studied. Anyway, the presentation of Pearson correlations in Table 1 already provides a sense of the bivariate associations between respective variables.

Finally, the present analyses were limited in the availability of potential covariates and religious measures. The SHARE-Israel sample did contain, for example, selected measures of household income, behavioral risks (e.g., smoking, drinking), and social support, but these were not included in the present analyses on account of a combination of large numbers of missing values, inappropriate time-referents, or non-standard wording for studies in this field. It would have been nice, of course, to have had access to a wider variety of religious indicators, including a measure of Jewish religious identity or observance (e.g., Israel’s haredi-dati-masorti-hiloni typology), but the lack here was balanced by the presence of six diverse mental health indicators, including four well known scales, each of which exhibited high internal-consistency reliability in this sample. The opportunity to take a deeper look at the religion-mental-health relationship than has been possible in previous studies was thus deemed too substantial to pass up.

Another advantage of the SHARE-Israel sample, incidentally, is the presence of numerous measures of physical as well as mental health. These include single-item measures of self-rated health, long-term health problems, and activity limitation (used in the present analyses), as well as multi-item indices of diagnosed chronic diseases and physical symptoms and both the ADL and IADL scales. These measures provide the opportunity to replicate the present analyses with respect to physical health, provided a reasonable theoretical rationale can be developed. The putative influence of one’s religious expression or upbringing on psychological or psychiatric markers, for better or worse, is well-established through hundreds of empirical studies and through both theory and clinical observation (see Koenig et al. 2012; Levin 2010). Why, precisely, the religious measures in this particular study would be predictive of, say, physical symptoms, past diagnoses of chronic diseases, or current functional health is less clear, as is what this would imply about Judaism or mean for the medical care of Jews. If a good case can be made, then a companion piece to the present paper will be written.

An important implication of these findings, as noted, is that the impact of synagogue participation for psychological well-being appears robust. A positive net effect was observed for a psychiatric measure of depressive symptoms (CES-D), for a psychosocial measure of quality of life (CASP-12), and for the psychological trait of optimism (LOT-R). Being active in synagogue thus appears to have value both as a primary-preventive force against depression and as a promoter of positive well-being. As each of these constructs was measured by overall summary scores of indices that have been validated as multidimensional, there is an opportunity for more in-depth follow-up analyses as to which dimensions of these respective constructs may be most impacted by religion or not impacted at all.

Because of how the synagogue variable was assessed in this study, we cannot identify just what it is about going to shul (synagogue) that is contributing to the salutary impact here. Is it access to the socially supportive resources that come with regular communal involvement with one’s coreligionists or chaverim (friends)? Is it repeatedly hearing and internalizing the positive and hopeful messages in the siddur (prayerbook) and from the rabbi’s divrei torah (sermons)? Is it the beneficial emotional sequelae of regular davvening (prayer)? Is it the behavioral reinforcement that accrues from the many prescriptions and proscriptions contained in the liturgy and that, ideally, exert a positive influence on one’s middot (character traits)? These functions of public religious participation could be protective against psychological distress and promotive of psychological well-being, alone or in combination (see, e.g., Levin 2010; Levin and Chatters 1998). But the item included in the SHARE dataset asked simply, “Have you done any of these activities in the last month?: Taken part in a religious organization (church, synagogue, mosque, etc.),” so the “how” and “why” of the present findings can only be inferred, if that, and not validated empirically. The “what” of these findings, on the other hand, is clearer, and encourages a closer look at how going to shul benefits well-being in other data sources, if available.

References

Achdut, L., & Litwin, H. (Eds.). (March, 2008). The 50+ cohort: First results from SHARE-Israel: Data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe [Special issue]. Social Security: Journal of Welfare and Social Security Studies, 76.

Amit, K. (2010). Determinants of life satisfaction among immigrants from Western countries and from the FSU in Israel. Social Indicators Research, 96, 515–534.

Amit, K., & Litwin, H. (2010). The subjective well-being of immigrants aged 50 and older in Israel. Social Indicators Research, 98, 89–104.

Andersson, G. (1996). The benefits of optimism: A meta-analytic review of the Life Orientation Test. Personal and Individual Differences, 21, 719–725.

Anson, O., Antonovsky, A., & Sagy, S. (1990). Religiosity and well-being among retirees: A question of causality. Behavior, Health, and Aging, 1, 85–97.

Anson, O., Levenson, A., Maoz, B., & Bonneh, D. Y. (1991). Religious community, individual religiosity, and health: A tale of two kibbutzim. Sociology, 25, 119–132.

Ayalon, L., Heinik, J., & Litwin, H. (2010). Population group differences in cognitive functioning in a national sample of Israelis 50 years and older. Research on Aging, 32, 304–322.

Börsch-Supan, A., Hank, K., & Jürges, H. (2005). A new comprehensive and international view on ageing: Introducing the “Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe.” European Journal of Ageing, 2, 245–253.

Castro-Costa, E., Dewey, M., Stewart, R., Banerjee, S., Huppert, F., Mendonca-Lima, C., et al. (2007). Prevalence of depressive symptoms and syndromes in later life in ten European countries. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191, 393–401.

Castro-Costa, E., Dewey, M., Stewart, R., Banerjee, S., Huppert, F., Mendonca-Lima, C., et al. (2008). Ascertaining late-life depressive symptoms in Europe: An evaluation of the survey version of the EURO-D scale in 10 nations. The SHARE project. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 17, 12–29.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Higgs, P., Hyde, M., Wiggins, R., & Blane, D. (2003). Researching quality of life in early old age: The importance of the sociological dimension. Social Policy and Administration, 37, 239–252.

Hyde, M., Wiggin, R. D., Higgs, P., & Blane, D. B. (2003). A measure of quality of life in early old age: The theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging and Mental Health, 7, 186–194.

Kark, J. D., Carmel, S., Sinnreich, R., Goldberger, N., & Friedlander, Y. (1996). Psychosocial factors among members of religious and secular kibbutzim. Israel Journal of Medical Sciences, 32, 185–194.

Koenig, H. G., King, D. E., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of Religion and Health (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Krause, N. M. (2008). Aging in the Church: How social relationships affect health. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press.

Landau, S. F., Beit-Hallahmi, B., & Levy, S. (1998). The personal and the political: Israelis’ perception of well-being in times of war and peace. Social Indicators Research, 44, 329–365.

Levav, I., Kohn, R., & Billig, M. (2008). The protective effect of religiosity under terrorism. Psychiatry, 71, 46–58.

Levin, J. (2010). Religion and mental health: Theory and research. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 7, 102–115.

Levin, J. (2011a). Health impact of Jewish religious observance in the USA: Findings from the 2000–01 National Jewish Population Survey. Journal of Religion and Health, 50, 852–868.

Levin, J. (2011b). Religion and positive well-being among Israeli and diaspora Jews: Findings from the World Values Survey. Mental Health, Religion and Culture (online prepublication).

Levin, J. (2011c). Religion and psychological well-being and distress in Israeli Jews: Findings from the Gallup World Poll. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 48, 252–261.

Levin, J. S., & Chatters, L. M. (1998). Research on religion and mental health: An overview of empirical findings and theoretical issues. In H. G. Koenig (Ed.), Handbook of Religion and Mental Health (pp. 33–50). San Diego: Academic Press.

Levin, J. S., & Taylor, R. J. (1998). Panel analyses of religious involvement and well-being in African Americans: Contemporaneous vs. longitudinal effects. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37, 695–709.

Litwin, H. (2009). Understanding aging in a Middle Eastern context: The SHARE-Israel Survey of persons aged 50 and older. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 24, 49–62.

Litwin, H., & Sapir, E. V. (2008). Methodology: The structure and content of the SHARE-Israel Survey. In H. Litwin (Ed.), The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE)-Israel, 2005–2006. ICPSR 22160 Codebook. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Lomsky-Feder, E., & Rapoport, T. (2001). Homecoming, immigration, and the national ethos: Russian-Jewish homecomers reading Zionism. Anthropological Quarterly, 74, 1–14.

Mirsky, J. (2009). The epidemiology of mental health problems among immigrants in Israel. In I. Levav (Ed.), Psychiatric and behavioral disorders in Israel: From epidemiology to mental health action (pp. 88–103). Jerusalem: Geffen Publishing House.

Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York: Guilford Press.

Pirutinsky, S., Rosmarin, D. H., Pargament, K. I., & Midlarsky, E. (2011). Does negative religious coping accompany, precede, or follow depression among Orthodox Jews? Journal of Affective Disorders, 132, 401–405.

Ponizovsky, A., Ginath, Y., Durst, R., Wondimeneh, B., Safro, S., Minuchin-Itzigson, S., et al. (1998). Psychological distress among Ethiopian and Russian Jewish immigrants to Israel: A cross-cultural study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 44, 35–45.

Prince, M. J., Reischies, F., Beekman, A. T. F., Fuhrer, R., Jonker, C., Kivela, S.-L., et al. (1999). Development of the EURO-D scale—a European Union initiative to compare symptoms of depression in 14 European centres. British Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 330–338.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Roll, A., & Litwin, H. (2010). Intergenerational financial transfers and mental health: An analysis using SHARE-Israel data. Aging and Mental Health, 14, 203–210.

Rosmarin, D. H., Krumrei, E. J., & Andersson, G. (2009a). Religion as a predictor of psychological distress in two religious communities. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38, 54–64.

Rosmarin, D. H., Krumrei, E. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2010). Do gratitude and spirituality predict psychological distress? International Journal of Existential Psychology & Psychotherapy, 3(1), 1–5.

Rosmarin, D. H., Pargament, K. I., & Flannelly, K. J. (2009b). Do spiritual struggles predict poorer physical/mental health among Jews? International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 19, 244–258.

Rosmarin, D. H., Pargament, K. I., & Mahoney, A. (2009c). The role of religiousness in anxiety, depression and happiness in a Jewish community sample: A preliminary investigation. Mental Health Religion & Culture, 12, 97–113.

Rosmarin, D. H., Pirutinsky, S., Cohen, A. B., Galler, Y., & Krumrei, E. J. (2011). Grateful to God or just plain grateful?: A comparison of religious and general gratitude. Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 389–396.

Rosmarin, D. H., Pirutinsky, S., Pargament, K. I., & Krumrei, E. J. (2009d). Are religious beliefs relevant to mental health among Jews? Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 1, 180–190.

Shkolnik, T., Weiner, C., Malik, L., & Festinger, Y. (2001). The effect of Jewish religiosity of elderly Israelis on their life satisfaction, health, function and activity. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 16, 201–219.

Shmotkin, D. (1990). Subjective well-being as a function of age and gender: A multivariate look for differentiated trends. Social Indicators Research, 23, 201–230.

Shmotkin, D., & Litwin, H. (2009). Cumulative adversity and depressive symptoms among older adults in Israel: The differential roles of self-oriented versus other-oriented events of potential trauma. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44, 989–997.

Shmueli, A. (2006). Health and religiosity among Israeli Jews. European Journal of Public Health, 17, 104–111.

Smith, T. B., McCullough, M. E., & Poll, J. (2003). Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 614–636.

Srole, L., & Langner, T. (1962). Religious origin. In L. Srole, T. S. Langner, S. T. Michael, M. K. Opler, & T. A. C. Rennie, Mental health in the metropolis: The Midtown Manhattan Study (pp. 300–324). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Summerlin, F. A. (Comp.). (1980). Religion and Mental Health: A Bibliography. DHHS Pub. No. (ADM) 80-964. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Vilchinsky, N., & Kravetz, S. (2005). How are religious belief and behavior good for you?: An investigation of mediators relating religion to mental health in a sample of Israeli Jewish students. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 44, 459–471.

Williams, D. R., Larson, D. B., Buckler, R. E., Heckmann, R. C., & Pyle, C. M. (1991). Religion and psychological distress in a community sample. Social Science and Medicine, 32, 1257–1262.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Levin, J. Religion and Mental Health Among Israeli Jews: Findings from the SHARE-Israel Study. Soc Indic Res 113, 769–784 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0113-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0113-x