Abstract

Background

The study examined the association between cumulative adversity and current depressive symptoms in a national sample of Israelis aged 50+. Referring to cumulative adversity as exposure to potentially traumatic events along life, the study distinguished between events primarily inflicted upon the self (self-oriented adversity) versus upon another person (other-oriented adversity).

Method

Data were drawn from the Israeli component of the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). During 2005–2006, 1710 Jews and Arabs completed an inventory of potentially traumatic events and two measures of depressive symptoms: the European Depression scale (Euro-D) and the Adapted Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression scale (ACES-D). The Euro-D is more detailed in querying cognitions and motivations while the ACES-D is more detailed in querying feelings and social alienation.

Results

In line with the hypothesis, self-oriented adversity had a positive association with depressive symptoms whereas other-oriented adversity had either no association or an inverse association with depressive symptoms. Sociodemographic characteristics and perceived health were controlled in the multivariate regressions.

Conclusions

The differential association of self- versus other-oriented adversity with depressive symptoms may be explained in terms of social commitments that are inherent in other-oriented adversity and incompatible with depressive symptoms. The study points to the variations in the symptom compositions represented by the Euro-D and ACES-D, with the latter better capturing the difference between self- and other-oriented adversities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Do traumatic events over the life course impair mental health in older age? Behind this question is the issue whether individuals can erase negative experiences in general [4] and traumatic experiences in particular [21]. A central aspect in this regard is the social context in which both the trauma and its sequelae are embedded. The present study addresses this question by examining the relationship of cumulative adversity in life with current depressive symptoms in a national sample of older Israelis. The study proposes a new way to view cumulative adversity by distinguishing whether such adversity focuses on the self or on others.

Cumulative adversity in epidemiological studies usually denotes lifetime exposure to potentially traumatic events, thus representing variability of different populations along a wide spectrum of traumatic experiences [33, 48, 59]. The rationale underlying this concept is that experiences accumulated over the lifetime exert a more lasting influence on physical and mental health than discrete events do. Thus, the limited difference theory of Cole and Singer [14] explicates that over shorter periods of time, single events produce limited differences on current outcomes; for extended periods of time, however, the accumulation of these limited differences produces a substantial impact. This assertion implies that variations in cumulated experiences allow different pathways to affect individuals [56]. Accordingly, consequences of prior trauma are better captured by considering exposure to multiple events than to one focal event only [18].

Cumulative adversity and mental health outcomes

Epidemiological studies differ in their definitions of traumatic and potentially traumatic events, the composition of the event inventories, the types of samples, and the age range of the respondents. These differences challenge the comparability of cumulative adversity across populations. Thus, reports of lifetime exposure to a traumatic event present a wide range of prevalence: 28% (midlife adults [20]), 65% (age 17–24 [18]), 69% (life-span adults [39]), and 89% (age 18–45 [8]). Despite this variability, studies indicate that traumatic, or potentially traumatic, events in childhood and adult life are likely to be related with current impairment of mental health as expressed by depressive symptoms and depression [24, 27, 59], risk of PTSD [8, 25, 37, 39, 49], reduced subjective well-being [28, 45], and various types of psychopathology [16, 40].

Most studies in this area provide one-time, cross-sectional data that may confound retrospectively reported events with concurrent responses to mental health measures. However, a few longitudinal studies confirm the assumed causal impact of cumulative adversity on mental health, although their follow-ups cover limited periods within the life-span [15, 57]. Another concern is the reliance of cumulative adversity studies on indices that sum up the number of traumatic (or potentially traumatic) events during one’s lifetime. Such indices are less relevant to models that posit interactive effects between factors inherent to adverse events, such as the events’ situational acuteness (e.g., the extent of uncontrollability and life threat) or psychological meaning (e.g., humiliation, entrapment) [12, 16]. However, as noted above, additive indices of cumulative adversity have their conceptual rationale, and, additionally, a heuristic and parsimonious value.

A distinction between self-oriented and other-oriented adversity

Although an additive index of cumulative adversity generally signifies an increasing psychological infliction, different kinds of adversity subsumed within such an index do not necessarily share a similar likelihood to affect mental health. In this interplay between a global and differential approach to cumulative adversity, prior research has largely overlooked the fundamental distinction between self-oriented and other-oriented adversity. This distinction is reflected by the definition of traumatic event in the DSM-IV criteria A1 and A2 for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): “(1) the person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others [italics added], (2) the person’s response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror” ([1], p. 467). In our opinion, the “self or others” distinction reflects whether the traumatic infliction primarily targets the self (e.g., being at risk of death due to illness or accident, being a victim of assault or abuse) or affects the self by primarily targeting others (e.g., witnessing people killed by violence, learning about the unexpected death of a loved one). This distinction is partially evident in classifications that aggregated certain other-oriented traumatic events into categories such as “learning about traumas to others” [8] or “witnessed violence” and “traumatic news” [33]. However, such classifications also included categories that mixed both self- and other-oriented events.

The “self or others” distinction gains more relevance since the DSM-IV has defined traumatic event in a wider scope than the DSM-III and DSM-III-R [7, 36], thus providing more options of “witnessing” and “learning about” stressors that may evoke trauma. In line with certain studies [18, 33], we adopt an even wider definition by which trauma may be evoked by a threat to the psychological (and not merely the “physical”) integrity of self or others. Thus, adverse conditions that do not ostensibly meet the DSM criterion A1 (e.g., experiencing severe economic deprivation, providing long-term care to a severely disabled family member) may be potentially traumatizing if they pervasively and chronically disrupt one’s ability to meet essential needs and goals [17, 37].

A prototypic example of other-oriented adversity, which complicates the self with the misfortunes occurring to others, is bereavement. While most people restore normal functioning after the loss of loved ones, a traumatic reaction may still stem from a failure to reorganize the internal relationship with the deceased [46]. Such a traumatic reaction to bereavement may not be easily detectable as normal grief reactions range from no apparent sadness at all to sizeable distress lasting for years [62]. Another relationship with a significant other that may undergo a traumatic transformation is caregiving to a disabled family member [19]. Other-oriented adversity may also be induced by exposure to horrific events such as war and terrorism [55]. In this case, identification with the original victims, whether because of their group identity or tragic ordeal, may replace an actual relationship with them [60]. Finally, sharing life with a traumatized person [5], and even relationships through giving professional help to trauma survivors, may generate “vicarious” or “secondary” traumatization [3].

The studies cited indicate that other-oriented adversity commonly concerns a socially framed relationship, which is put to the test of an extreme strain or loss. As both self-oriented and other-oriented adversity may have an interpersonal nature [18], it is not the interpersonal encounter that distinguishes between the two but rather the social commitment that accompanies other-oriented adversity. Commitment is an essential ingredient of valued relationships and becomes stronger in adversity [10, 35]; hence, a higher risk for depression is linked with a failure to maintain one’s commitment in core relationships [12]. For example, having a close relative in critical danger often requires family members to act. Similarly, the death of a loved one often imposes an immediate obligation to care for others. Even disastrous inflictions perpetrated on strangers (by crime, war, or terrorist acts) call upon the immediate witnesses to fulfil social duties such as providing emergency help or bearing witness. Hence, persons exposed to other-oriented adversity must often exercise social responsibility, and debilitating effects on their part (e.g., depressive reactions) must be limited, deferred or declined. In contrast, persons exposed to self-oriented adversity have more freedom to be absorbed in their own injurious feelings. Thus, the role of a socially identified victim is more easily assigned to those who undergo self-oriented, rather than other-oriented, adversity.

Overview of the database and the hypotheses

The present study analyzed data drawn from SHARE-Israel, the Israeli component of the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Based on the American Health and Retirement Study (HRS), SHARE provides nationwide, multi-dimensional assessments of middle-aged and older people in 15 countries [6]. So far, the assessment of traumatic events in this project is unique to the SHARE-Israel sample. Studies on the impact of lifetime adversity on older adults are still few, even though old age presents pertinent questions about the persistence of posttraumatic effects and their interaction with aging-related adversity [2, 49].

Our initial hypothesis is that overall cumulative adversity in life is positively associated with current depressive symptoms beyond the effects of sociodemographic characteristics and perceived health. These covariate effects often entail aspects of stressful life in their own right, such as age-related decline, ethnic group-related disadvantage, deficient resources due to lower socioeconomic status and limitations imposed by health problems. Nevertheless, we maintain that cumulative adversity adds a unique explanation to depressive symptoms, thus reflecting the particular role of traumatic events in overriding subjective well-being and in shaping hostile-world scenarios [52].

Within the concept of cumulative adversity, a second hypothesis maintains that self-oriented adversity is more strongly associated with current depressive symptoms than is other-oriented adversity, beyond the effects of sociodemographic characteristics and perceived health. This hypothesis is corroborated by prior findings that specific self-oriented events (e.g., being victim to assaultive violence) related to a higher probability of PTSD than other-oriented events (e.g., unexpected death of a close relative/friend) [9, 39]. We do not claim, however, that other-oriented adversity has a lower impact on one’s life. Rather, based on aforementioned models [10], we assume that persons exposed to other-oriented adversity have social commitments which make depressive symptoms inappropriate and obstructive. Adjustment for the perceived health covariate is particularly relevant here, because those exposed to self-oriented adversity are the ones whose health is likely to be directly harmed by injury or illness [29].

Methods

Participants and procedure

Data were drawn from SHARE-Israel, which presents a national sample of Israelis aged 50 or older and their spouses regardless of age, interviewed during 2005–2006. The design was based upon a probability sample of households within 150 representative statistical areas delineated by geographical and sociodemographic criteria. The Israeli database included 2,598 noninstitutionalized adults in 1,771 households. The participants were interviewed in Hebrew, Russian or Arabic. Data were collected by a comprehensive computer-assisted personal interview, which lasted about 90 min, and a supplementary paper Drop-Off questionnaire, which was returned later [32]. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the interview. SHARE-Israel received ethical approval by the Institutional Review Board of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Uniquely included in the Israeli Drop-Off questionnaire was a measure of lifetime adversity that constitutes the focus of the present analysis. Hence, the present sample is limited to the Drop-Off respondents (N = 1710, 66% of the total sample). Compared with non-respondents who did not complete the Drop-Off, the Drop-Off respondents were similar in gender, education, and gross individual income. However, the latter had a lower proportion of immigrants from the former Soviet Union, a higher proportion of Arab Israelis, and younger (below 60) and married respondents.

Measures

The present analysis addressed the following sociodemographic characteristics: age, gender, ethnic origin (Israeli-born Jews; immigrants from the Middle East or North Africa, Europe or America, and the former Soviet Union; and Arab Israelis); education (seven categories ranked from no schooling to graduate academic degree); annual gross household income (in Euro), and marital status (married versus currently unmarried, the latter including never married, divorced, and widowed). Perceived health status was self-rated on a 5-step scale ranging from “very poor” to “very good.” The use of this measure in SHARE [6] followed equivalent scales common in health research [41].

European depression scale (Euro-D)

Adopted by SHARE, this measure was initially designed to integrate different depression measures in 11 European countries [43]. It contains 12 items of recent depressive symptoms (e.g., “In the last month, have you cried at all?”), scored as a sum of “yes” (1, indicating presence of a symptom) and “no” (0) encoded answers. Five items were phrased in positive terms (e.g., “what have you enjoyed doing recently?”; failing to mention any enjoyable activity was scored 1). In the present analysis, a minimum of 80% completion (10 items) was required for scoring, with scores of 10–11 items being interpolated by assigning the respondent’s mean of the completed items to the missing one. A sum score of zero (no symptoms) was given to 18.7% of the participants (Median = 2.00, M = 2.80, SD = 2.52). The Euro-D manifested sound measurement properties in European representative samples [13]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in the Israeli database was 0.75 (in European countries alpha ranged from 0.62 to 0.78 [13]).

Adapted version of the center for epidemiological studies—depression scale (ACES-D)

Based on the 20-item CES-D [44], this measure was employed by SHARE in its Drop-Off questionnaire. SHARE adopted the 14-item version that was introduced in the first wave of HRS, in which 11 items pertained to the original CES-D and three others were borrowed from parallel measures. Each item specified a depressive symptom (e.g., “I felt sad”). Respondents were asked to rate the frequency they had experienced each item in the last week on a scale that ranged from “almost none of the time” (0) to “almost all of the time” (3). Four items were phrased positively (e.g., “I was happy”) and reverse coded. The respondent’s score was the sum of ratings over all items. In the present analysis, a minimum of 80% completion (11 items) was required for scoring, with scores of 11–13 items being interpolated as noted above. A sum score of zero (no symptoms) was given to 1.1% of the participants (Median = 13.00, M = 13.56, SD = 7.04). Shortened versions of the CES-D, similar to the one used here, showed psychometric properties that approximated those of the original CES-D [26, 58]. The alpha coefficient in the Israeli database was 0.87.

The Euro-D and ACES-D share similar items (e.g., feeling depressed, no enjoyment, troubled sleeping, reduced appetite, lack of energy). Yet, the Euro-D items include cognitions and motivations not queried in the ACES-D (e.g., wishing to die, self-blame, not having hopes for the future, losing interest, failure to concentrate), whereas the ACES-D items are more dominantly phrased as feelings rather than facts, and refer to interpersonal symptoms not queried in the Euro-D (feeling lonely, feeling people being unfriendly, feeling people as disliking). The correlation between the Euro-D and ACES-D in the present sample was 0.60 (p < .001).

Potentially traumatic events inventory

Based on Breslau et al.’s survey of lifetime traumatic events [8] and a pilot version administered to older Israelis, this inventory was adapted especially for the Drop-Off questionnaire in SHARE-Israel [53]. Selected items were added or changed in order to reflect pertinent experiences in old age (e.g., caregiving and bereavement) and in the Israeli context (e.g., war and terrorism). Other items were condensed (e.g., rape and other kinds of sexual assault) or omitted in case of low self-rated impact in the pilots. Respondents were asked to check whether each of 17 “difficult life events” had ever happened to them. They also gave information (not reported in the present paper) about their age at the time of checked events and the perceived impact of those events. Overall cumulative adversity was scored as the number of events that the respondent confirmed to have experienced. Two additional scores derived for each respondent were self-oriented adversity, i.e., the number of confirmed events in which the primary infliction was upon the self, and other-oriented adversity, i.e., the number of confirmed events in which the primary infliction was upon another person. Table 1 specifies the self- and other-oriented potentially traumatic events (8 and 9 items, respectively). The correlation between self-oriented adversity and other-oriented adversity in the present sample was 0.46 (p < .001).

Statistical analyses

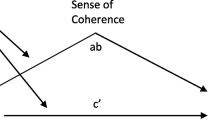

Following execution of univariate and bivariate examinations of cumulative adversity, we tested two models predicting depressive symptoms, indicated by the Euro-D and by the ACES-D, using hierarchical multiple linear regression. In Step 1, both models included sociodemographic variables and perceived health. In Step 2, Model 1 introduced the general score of cumulative adversity whereas Model 2 introduced the self-oriented and the other-oriented scores, simultaneously. An interaction term of both kinds of adversity was also tested in a third step of Model 2.

Results

Incidence and correlates of cumulative adversity

While 24.1% of the respondents reported experiencing none of the 17 potentially traumatic events, 53.4% reported from one to three events and an additional 22.6% reported four or more (Median = 2.0; M = 2.3; SD = 2.3). The most frequently reported events (Table 1) were having had a loved one at risk of death due to illness or accident and having provided long-term care to a disabled or impaired relative (37.1% and 35.6%, respectively). Next in frequency were the events of having experienced extremely severe economic deprivation and having lost a loved one in war or military service (23.3% and 20.4%, respectively).

Table 2 shows that higher cumulative adversity was significantly correlated with a higher age, male gender, marital status (currently unmarried), and lower perceived health.

Testing the association of cumulative adversity with depressive symptoms

Model 1 of the hierarchical multiple regressions (Table 3) showed that cumulative adversity significantly predicted depressive symptoms in the Euro-D after controlling for sociodemographic and perceived health effects (β = .077, p < .001), but not in the ACES-D (β = –.006, ns). This result lent partial support to the first hypothesis. Also, the Euro-D and ACES-D scores were both predicted by female gender, Middle-Eastern or North African origin (compared to Israeli-born), lower education, marital status (currently unmarried), and low perceived health. The ACES-D score was additionally predicted by higher age, former Soviet Union and Israeli-Arab origin (compared to Israeli-born), and lower income.

Testing the associations of self- and other-oriented adversity with depressive symptoms

Model 2 of the regressions (Table 3), which controlled for the simultaneous effects of self-oriented and other-oriented adversity as well as for other effects of sociodemographics and perceived health, showed that self-oriented adversity significantly predicted depressive symptoms in both the Euro-D (β = .060, p < .05) and the ACES-D (β = .061, p < .01). Moreover, other-oriented adversity failed to predict depressive symptoms in the Euro-D (β = .029, ns) and demonstrated a reverse association with depressive symptoms in the ACES-D (β = –.065, p < .01). That is, higher other-oriented adversity was related to lower depressive symptoms among people with the same level of self-oriented adversity. The results of Model 2 thus gave full support to the second hypothesis. An additional analysis (not shown in the table) entered an interaction term between self-oriented and other-oriented adversity, and yielded non-significant beta coefficients of −0.01 and −0.02 in predicting the Euro-D and ACES-D, respectively.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated a positive association of cumulative adversity, measured by lifetime exposure to potentially traumatic events, with current depressive symptoms in a national sample of Israelis aged 50 and over. This association was significant beyond sociodemographic and perceived health effects. However, differential analyses revealed that within cumulative adversity, it was self-oriented adversity (potentially traumatic events primarily inflicted upon the self) that showed a positive association with depressive symptoms. In contrast, other-oriented adversity (potentially traumatic events primarily inflicted upon another person) showed no association—or even a negative association—with depressive symptoms. These results support the study hypothesis that self-oriented and other-oriented adversity yield differential mental health consequences when each is net of the effect of the other, and when sociodemographic and perceived health effects are controlled for. Accordingly, the initial hypothesis about the consequences of overall cumulative adversity (self- and other-oriented combined) received only partial support, as the cumulative measure showed a positive association with one indicator of depressive symptoms (Euro-D), but not with the other (ACES-D).

The differential findings were further accentuated by the result that the ACES-D, and not the Euro-D, revealed the inverse association with depressive symptoms by other-oriented adversity. Thus, the effect of self-oriented adversity permeated the whole spectrum of depressive symptoms: anhedonic and psychosomatic manifestations (assessed by both the Euro-D and ACES-D; see the comparative description in Measures, above), cognitions and motivations signifying loss of worth and purpose (predominantly assessed by the Euro-D), and feelings of social alienation and social withdrawal (predominantly assessed by the ACES-D). On the other hand, the inverse effect of other-oriented adversity on depressive symptoms, as assessed by the ACES-D, reflects a particular incompatibility with symptoms hindering social involvement. Hence, the findings conform to our rationale that people exposed to other-oriented adversity, even if traumatized through this exposure, face social imperatives stemming from the relationships and the related commitments affected by that adversity.

The results suggest, therefore, that the use of two measures of depressive symptoms in SHARE was complementary. It helped to delineate differential effects of life stress on subtypes of depressive symptoms and possibly of depression [38]. Hence, while the literature presents well-formulated, factorial compositions within individual measures of depressive symptoms [13, 22], more research is needed to evaluate how depressive symptoms function as mental health outcomes according to distinct measures coming from different traditions [50].

The impact of cumulative adversity on depressive symptoms needs to be seen in the context of the other factors examined in this study. As expected, low perceived health was related to depressive symptoms [41]. Sociodemographic characteristics in the present Israeli sample also replicated largely universal findings. Thus, depressive symptoms were related to being female, older, widowed, and of lower socioeconomic status [11, 42]. As for origin, which is an Israeli-bound characteristic, participants born in Israel presented a lower level of depressive symptoms relative to immigrants from the Middle East or North Africa and the former Soviet Union, as well as to Arab Israelis. This finding may reflect differences in access to resources and social positions [30, 47].

Another epidemiological implication concerns the characteristic level of depression in the present Israeli sample. Threshold scores that signal probable clinical depression, whether by the Euro-D in the present survey [53] or by the original CES-D in a previous national survey [54], indicated that the likelihood of depression in the older population of Israel is nearly twice as high as expected among populations of similar age in the US and most European countries. This elevated level of depression may be attributed to highly stressful events that many older Israelis endured [31, 34, 51]. Future research should examine whether results emerging in a susceptible population, both in terms of traumatic events and elevated depression, can be generalized to other populations.

Relying on cross-sectional, rather than longitudinal, data, this study cannot formulate a causal interpretation of the results. However, it is plausible that cumulative adversity increases the proneness to depressive symptoms in later life. This interpretation is in line with longitudinal studies and the incremental knowledge obtained by cross-sectional studies [33], although a paradoxical effect of increasing immunity after exposure to trauma is also possible [61]. An alternative interpretation holds that predisposition to depression exacerbates traumatic events in life or increases the tendency to remember and report traumatic events [24]. However, that interpretation poses a difficulty in explaining why depressive symptoms are positively associated with self-oriented, rather than other-oriented, adverse events.

The present study has additional limitations that should be addressed in future research. Thus, the study did not address PTSD which is often considered a relevant outcome in studies of cumulative adversity. However, PTSD risk concerns relatively small portions of the population, approximating one-tenth of persons exposed to a particular trauma [9]. The advantage of using depressive symptoms in research is their applicability to large community populations as well as their sensitivity to both clinical and subclinical conditions [23]. Furthermore, the study did not address the role of positive mental health factors (e.g., subjective well-being, coping, and meaning in life) that could possibly modulate the negative effects of cumulative adversity [52].

Conclusion

The present study contributes a new view on the link between cumulative adversity in life and current depressive symptoms. We proposed a distinction between self-oriented and other-oriented adversity, based on the implications of social commitment in adverse conditions. The results of the inquiry confirmed that self-oriented, but not other-oriented, adversity is positively associated with current depressive symptoms. Hence, this study points to the social focus of potentially traumatic events as a key component for understanding the cumulative effect of such adversity on mental health in late life.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR), 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

Averill PM, Beck JG (2000) Posttraumatic stress disorder in older adults: a conceptual review. J Anxiety Disorders 14:133–156

Baird K, Kracen AC (2006) Vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress: a research synthesis. Counsel Psychol Q 19:181–188

Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD (2001) Bad is stronger then good. Rev Gen Psychol 5:323–370

Ben Arzi N, Solomon Z, Dekel R (2000) Secondary traumatization among wives of PTSD and post-concussion casualties: distress, caregiver burden and psychological separation. Brain Inj 14:725–736

Börsch-Supan A, Brugiavini A, Jürges H, Mackenbach J, Siegrist J, Weber G (2005) Health, ageing and retirement in Europe: first results from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging, Mannheim

Breslau N, Kessler R (2001) The stressor criterion in DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder: an empirical investigation. Biol Psychiatry 50:699–704

Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilicoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P (1998) Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit area survey of trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55:626–632

Breslau N, Peterson EL, Poisson LM, Schultz LR, Lucia VC (2004) Estimating post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: lifetime perspective and the impact of typical traumatic events. Psychol Med 34:889–898

Brickman P, Coates D (1987) Commitment and mental health. In: Wortman CB, Sorrentino R (eds) Commitment, conflict, and caring. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, pp 222–276

Brodaty H, Cullen B, Thompson C, Mitchell P, Parker G, Wilhelm K et al (2005) Age and gender in the phenomenology of depression. Am J Ger Psychiatry 13:589–596

Brown GW (2002) Social roles, context and evolution in the origins of depression. J Health Soc Beh 43:255–276

Castro-Costa E, Dewey M, Stewart R, Banerjee S, Huppert F, Mendonca-Lima C et al (2008) Ascertaining late-life depressive symptoms in Europe: an evaluation of the EURO-D scale in 10 nations—the SHARE project. Int J Methods Psychiatric Res 17:12–29

Cole JR, Singer B (1991) A theory of limited differences: explaining the productivity puzzle in science. In: Zuckerman H, Cole JR, Bruer JT (eds) The outer circle: women in the scientific community. Norton, New York, pp 277–339

Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ (2007) Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:577–584

Dohrenwend BP (2000) The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: some evidence and its implications for theory and research. J Health Soc Beh 41:1–19

Gold SD, Marx BP, Soler-Baillo JM, Sloan DM (2005) Is life stress more traumatic than traumatic stress? Anxiety Disorders 19:687–698

Green BL, Goodman LA, Krupnick JL, Corcoran BL, Petty RM, Stockton P et al (2000) Outcomes of single versus multiple trauma exposure in a screening sample. J Traumatic Stress 13:271–286

Hebert RS, Schulz R (2006) Caregiving at the end of life. J Palliat Med 9:1174–1187

Hepp U, Gamma A, Milos G, Eich D, Ajdacic-Gross V, Rossler W et al (2006) Prevalence of exposure to potentially traumatic events and PTSD: the Zurich cohort study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 256:151–158

Herman JL (1992) Trauma and recovery. Basic Books, New York

Hertzog C, Van Alstine J, Usala PD, Hultsch DF, Dixon R (1990) Measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in older populations. Psychol Assessment: J Consult Clin Psychol A 2:64–72

Hybles CG, Blazer DG, Pieper CF (2001) Toward a threshold for sub-threshold depression: an analysis of correlates of depression by severity of symptoms using data from an elderly community sample. Gerontologist 41:357–365

Kessler RC (1997) The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu Rev Psychol 48:191–214

Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB (1995) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52:1048–1060

Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J (1993) Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health 5:179–193

Kraaij V, de Wilde EJ (2001) Negative life events and depressive symptoms in the elderly: a life span perspective. Aging Ment Health 5:84–91

Krause N (2004) Lifetime trauma, emotional support, and life satisfaction among older adults. Gerontologist 44:615–623

Krause N, Shaw BA, Cairney J (2004) A descriptive epidemiology of lifetime trauma and the physical health status of older adults. Psychol Aging 19:637–648

Lancu L, Horesh N, Lepkifker E, Drory Y (2003) An epidemiological study of depressive symptomatology among Israeli adults: prevalence of depressive symptoms and demographic risk factors. Israel J Psychiatry Rel Sci 40:82–89

Litwin H (1995) Uprooted in old age: Soviet Jews and their social networks in Israel. Greenwood, Westport, CT

Litwin H, Sapir EV (2008) The SHARE-Israel methodology. In: Achdut, L, Litwin H (eds) The 50+ cohort: first results from SHARE-Israel—Data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (special issue of Social Security [Bitachon Sociali], No. 76, 25–42). The National Insurance Institute of Israel, Jerusalem (in Hebrew)

Lloyd DA, Turner RJ (2003) Cumulative adversity and posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from a diverse community sample of young adults. Am J Orthopsychiatry 73:381–391

Lomranz J (1990) Long-term adaptation to traumatic stress in light of adult development and aging perspectives. In: Stephens MP, Crowther J, Hobfoll SE, Tenenbaum D (eds) Stress and coping in later-life families. Hemisphere, New York, pp 99–121

Lydon JE, Zanna MP (1992) The cost of social support following negative life events: can adversity increase commitment to caring in close relationships? In: Montada L, Filipp SH, Lerner MJ (eds) Life crises and experiences of loss in adulthood. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp 461–475

McNally RJ (2003) Progress and controversy in the study of posttraumatic stress disorder. Annu Rev Psychol 54:229–252

Mol SSL, Arntz A, Metsemakers JFM, Dinant GJ, Vilters-van Monfort PAP, Knottnerus JA (2005) Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder after non-traumatic events: evidence from an open population study. Br J Psychiatry 186:494–499

Monroe SM, Harkness K, Simons AD, Thase ME (2001) Life stress and the symptoms of major depression. J Nerv Ment Disease 189:168–175

Norris FH (1992) Epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. J Consult Clin Psychol 60:409–418

Paykel ES (2003) Life events and affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 108(Suppl. 418):61–66

Pinquart M (2001) Correlates of subjective health in older adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging 16:414–426

Prince MJ, Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, Fuhrer R, Kivela SL, Lawlor BA et al (1999) Depression symptoms in late life assessed using the EURO-D scale: effect of age, gender and marital status in 14 European centres. Br J Psychiatry 174:339–345

Prince MJ, Reischies F, Beekman ATF, Fuhrer R, Jonker C, Kivela SL et al (1999) Development of the Euro-D scale—a European Union initiative to compare symptoms of depression in 14 European centres. Br J Psychiatry 174:330–338

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure 1:385–401

Royse D, Rompf EL, Dhooper SS (1993) Childhood trauma and adult life satisfaction. J Appl Soc Sci 17:179–189

Rubin SS, Malkinson R, Witztum E (2000) Loss, bereavement and trauma: an overview. In: Malkinson R, Rubin SS, Witztum E (eds) Traumatic and nontraumatic loss and bereavement: clinical theory and practice. Psychosocial Press, Hillsdale, NJ, pp 5–40

Ruskin P, Blumstein T, Walter-Ginzburg A, Fuchs Z, Lusky A, Novikov I et al (1996) Depressive symptoms among community-dwelling oldest-old residents in Israel. Am J Ger Psychiatry 4:208–217

Ryff CD, Singer B, Love GD, Essex MJ (1998) Resilience in adulthood and later life: defining features and dynamic processes. In: Lomranz J (ed) Handbook of aging and mental health: an integrative approach. Plenum, New York, pp 69–99

Schnurr PP, Spiro AIII, Vielhauer MJ, Findler MN, Hamblen JL (2002) Trauma in the lives of older men: findings from the normative aging study. J Clin Geropsychol 8:175–187

Shafer AB (2006) Meta-analysis of the factor structures of four depression questionnaires: Beck, CES-D, Hamilton, and Zung. J Clin Psychol 62:123–146

Shmotkin D (2003) Vulnerability and resilience intertwined: a review of research on Holocaust survivors. In: Jacoby R, Keinan G (eds) Between stress and hope: from a disease-centered to a health-centered perspective. Praeger, Westport, CT, pp 213–233

Shmotkin D (2005) Happiness in the face of adversity: reformulating the dynamic and modular bases of subjective well-being. Rev Gen Psychol 9:291–325

Shmotkin D (2008) Mental health and trauma among Israelis aged 50+. In: Achdut L, Litwin H (eds) The 50+ cohort: first results from SHARE-Israel—Data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (special issue of Social Security [Bitachon Sociali], No. 76, 197–224). The National Insurance Institute of Israel, Jerusalem (in Hebrew)

Shmotkin D, Blumstein T, Modan B (2003) Tracing long-term effects of early trauma: a broad-scope view of Holocaust survivors in late life. J Consult Clin Psychol 71:223–234

Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, Poulin M, Gil-Rivas V (2002) Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. J Am Med Assoc 288:1235–1244

Singer B, Ryff CD, Carr D, Magee WJ (1998) Linking life histories and mental health: a person-centered strategy. Sociol Methodol 28:1–5

Stallings MC, Dunham CC, Gatz M, Baker LA, Bengtson VL (1997) Relationships among life events and psychological well-being: more evidence for a two-factor theory of well-being. J Appl Gerontol 16:104–119

Suthers KM, Gatz M, Fiske A (2004) Screening for depression: a comparative analysis of the 11-item CES-D and the CIDI-SF. J Ment Health Aging 10:209–219

Turner RJ, Lloyd DA (1995) Lifetime traumas and mental health: the significance of cumulative adversity. J Health Soc Behav 36:360–376

Wayment HA (2004) It could have been me: vicarious victims and disaster-focused distress. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 30:515–528

Wheaton B, Roszell P, Hall K (1997) The impact of twenty childhood and adult traumatic stressors on the risk of psychiatric disorder. In: Gotlib IH, Wheaton B (eds) Stress and adversity over the life course: trajectories and turning points. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp 50–72

Wortman CB, Silver RC (2001) The myths of coping with loss revised. In: Stroebe M, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, Schut H (eds) Handbook of bereavement research: consequences, coping, and care. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp 405–430

Acknowledgments

The SHARE (Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe) data collection in Israel was funded by the US National Institute on Aging (R21 AG2516901), by the German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development (G.I.F.), and by the National Insurance Institute of Israel. Further support by the European Commission through the 6th framework program (projects SHARE-I3, RII-CT-2006-062193, and COMPARE, CIT5-CT-2005-028857) is gratefully acknowledged. We are thankful to Eli Sapir for the indispensable help in handling the database and to Rany Abend for the devoted assistance in conducting the statistical analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shmotkin, D., Litwin, H. Cumulative adversity and depressive symptoms among older adults in Israel: the differential roles of self-oriented versus other-oriented events of potential trauma. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 44, 989–997 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0020-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0020-x