In the context of improved disclosure and greater transparency, including cash flow in our earnings release has helped increase investor confidence in our guidance as well as in the analyst’s estimates by giving them the tools they need to do their jobs.

Jim Clippard, Vice President of Investor Relations, FedEx.

From Randerson (2004, p. 50).

Abstract

We test for the effect of limited attention on the valuation of accruals by comparing the immediate and long-term market reactions to earnings announcements between a subsample of firms that disclose only the balance sheet with a subsample of firms that disclose both the balance sheet and the statement of cash flows (SCF) in the earnings press release. Information about accruals generally can be inferred from comparative balance sheets, but the availability of the SCF makes accruals more salient and easier to process for investors with limited attention. Controlling for potential additional information and endogeneity of SCF disclosure, we find strong evidence that SCF disclosure enables more efficient pricing of accruals. Further analyses using a proxy for investor sophistication suggest that, when SCF is absent from the earnings press release, less sophisticated investors fail to discount accruals but sophisticated investors do.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

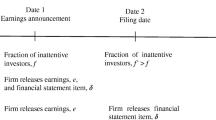

Current disclosure regulation in the U.S. does not require companies to provide complete financial statements in quarterly earnings releases. As a result, the choice of GAAP line items disclosed at earnings announcements varies significantly across firms (D’Souza et al. 2010). While it has become common in recent years for firms to include a balance sheet in addition to the income statement in the earnings release, voluntary disclosure of items from the statement of cash flows (SCF) remains relatively infrequent.Footnote 1 In this study, we examine whether the additional SCF disclosure in the earnings press release that contains the balance sheet affects the equity market’s ability to value accruals efficiently.

In an informationally efficient capital market, prices are determined as if investors were fully attentive. Since accruals generally can be deduced from the income statement and comparative balance sheets, if this information is disclosed in the earnings release, market prices properly incorporate information about accruals at the earnings announcement date. The additional availability of the SCF in the earnings release, therefore, is redundant for the efficient pricing of accruals in a frictionless capital market.

The seminal tests of Sloan (1996), however, show that the market fixates on earnings and overweighs accruals by failing to discount adequately for the lower persistence of the accrual component relative to the cash flow component of earnings; see also Hand (1990). This evidence is consistent with a large body of evidence suggesting that the capital market pricing of other accounting information is sometimes inefficient.Footnote 2 These accounting-based anomalies have encouraged the development of theoretical models to explain mispricing. One such class of models relies on limited attention, which the psychology literature suggests is an important and inescapable source of cognitive bias.Footnote 3 As explained in more detail in Sect. 2, attention to an information signal is a prerequisite for any cognitive processing of the signal, so the salience of the signal is important for the efficient pricing of the signal.

To explore how salience affects the market pricing of accruals, we test predictions from the Hirshleifer et al. (2011) model of the accrual anomaly. In the model, attentive investors are rational and update their priors fully upon arrival of new information according to Bayes Theorem, and inattentive investors ignore accrual information and therefore fail to incorporate the differential persistence of accruals versus cash flows for forecasting future earnings to value the firm. Accruals have lower persistence than cash flows for future earnings, so attentive investors discount accruals relative to cash flows when valuing the firm. When there are also inattentive investors, the model predicts that accruals will be insufficiently discounted, and so, on average, the firm will be overvalued.

Furthermore, the model predicts that the amount of overvaluation decreases with the degree of attention paid to accruals. When accruals are presented in a more salient manner, investors are more likely to pay attention to them and discount them appropriately than when accruals are nonsalient. In other words, the model predicts that the amount of accrual overvaluation decreases with the salience of accruals.

We use the earnings announcement as a setting to test this hypothesis by identifying variations in the salience of accruals information. Investors can obtain information about accruals from comparative balance sheets or from the SCF when these statements are presented in the earnings press release. We posit that accruals are more salient to investors when the SCF is presented, as it is cognitively less challenging to estimate accruals from SCF than from comparative years’ balance sheets (see Sect. 2).Footnote 4

Importantly, our tests control for public availability of accruals information at the earnings announcement by restricting the test sample to firms that disclose balance sheets in the earnings release. Within this sample, we compare how investors discount accruals when the SCF is present versus when it is absent from the earnings press release. We test for whether investors discount accruals differently across these two subsamples at the earnings announcement date, 10-K/Q filing date, and over the subsequent 12 months from the earnings announcement date. Insufficient discounting of high accruals would lead to overweighting of accruals at earnings announcement followed by a reversal—either at the 10-K/Q filing date when all financial statements are filed with the S.E.C. and made available publicly or later when the earnings anticipated based upon the level of past accruals do not materialize.

Our study differs from past studies by Baber et al. (2006), Levi (2008), and Louis et al. (2008) that find that the availability of accrual information at the earnings announcement helps investors discount accruals appropriately and mitigates accrual mispricing. Since only firms that disclose the balance sheet are included in our sample of earnings press releases, the availability of accrual information is held constant in our tests. Unlike the past studies, our focus therefore is on the difference in salience of the accruals information between the subsample of firms that withhold the SCF versus the subsample of firms that additionally disclose the SCF.

Furthermore, the sample periods of the past studies are short, one to three years, and these studies examine periods during the 1990s or early 2000s when SCF disclosure in earnings releases was relatively rare. Because of this infrequency, the authors mainly attribute their results to a balance sheet disclosure, not SCF disclosure. In contrast, our sample covers a much longer period, from 2000 to 2012, and is much larger.

Our study contributes to the academic literature in the important and continuing research on explanations for accounting anomalies and to research on the effects of limited attention and financial disclosures for the efficient functioning of the capital markets. Our study provides a comprehensive and large sample analysis of the capital market consequence from the additional disclosure of SCF for firms that already disclose the balance sheet in the earnings announcement. The findings from our tests on whether capital market participants, ranging from naïve investors to professional investors and analysts, are subject to salience effects have implications for capital market efficiency. A finding that format affects salience and ease of processing would suggest that regulators should consider not just content but also format of presentation when evaluating disclosure requirements.

Our study also has relevance for various professional entities concerned about the adequacy of financial disclosures for capital market participants. For example, the National Investor Relations Institute’s (NIRI) Standards of Practice for Investor Relations (2008) urges firms to include in their earnings release a balance sheet and a statement of cash flows, in addition to the traditional income statement. The Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) Institute (2007) and the S.E.C.’s Committee on Improvements in Financial Reporting (CIFiR, also commonly called the Pozen committee 2008) make similar recommendations. These professional entities argue that SCF disclosure in earnings announcements reduces information acquisition and attention costs and so lessens the informational disadvantage for less sophisticated participants, which would encourage greater capital market efficiency. We test whether the alleged benefits of improved salience of accruals, and hence more accurate investor and analyst valuation of accruals, from additional SCF disclosure in the earnings press release obtain.

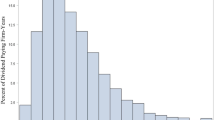

Our initial sample where balance sheets are provided in the earnings release comprises over 59,000 quarterly earnings announcements from 2000 to 2012. In about 30 % of the total sample, firms also provide SCF information. We find that the market discounts accruals at the earnings announcement date but by not enough, so investors continue to discount them over the subsequent 12 months. (We refer to the negative coefficient on accruals in a regression of event period returns on accruals and controls as accrual discounting.) In other words, investors overweight accruals at the earnings announcement date. This verifies that there is an accrual anomaly for our recent sample period, consistent with prior studies (Sloan 1996; Teoh and Zhang 2011).

In strong support for the salience hypothesis, we find that accrual discounting at the earnings announcement is three times greater for firms disclosing SCF than for firms withholding SCF. The acceleration of investors’ incorporation of accrual information in price is consistent with the SCF disclosure making accruals more salient, so that investors can better impound the information into price sooner. Also consistent with this hypothesis, the magnitude of the accrual anomaly for SCF disclosers is only half that for SCF withholders.

An alternative explanation to salience for the greater accrual mispricing for SCF withholders may be that the SCF contains incremental information over the balance sheet that is relevant for accrual discounting. If so, the accrual mispricing would be corrected by the time the SCF is mandated to be disclosed at the 10-K/Q filing date. We do not find evidence that the weaker accruals discounting by SCF withholders at the earnings release date is made up by the filing date, which is inconsistent with this alternative explanation. While SCF withholders discount accruals at twice the amount of SCF disclosers at the filing date, the combined accruals discounting at both earnings announcement and filing dates by SCF withholders is only half that of SCF disclosers.

A salience explanation for the results is therefore more compelling. Among investors who are inattentive to accruals when SCF is withheld at the earnings release date, some remain inattentive to the 10-K/Q filing event. In other words, SCF disclosure at the subsequent 10-K/Q filing date does not substitute for SCF disclosure at the earnings release date.

A potential explanation for our finding of weaker accrual discounting by SCF withholders at the earnings announcement is that SCF withholders have higher accrual persistence. We find the opposite to be true for our sample using two measures of accrual persistence, and therefore salience, not other uncontrolled for firm fundamental factors, explains our findings.

To provide corroborating evidence for the salience hypothesis, we examine whether analysts are also subject to salience effects. The answer is positive. We find that accruals can indeed better predict analysts forecast errors for SCF withholders than SCF disclosers. This result supports calls by regulatory agencies and investment professionals for SCF disclosure in the earnings release and suggests that inadequate risk controls are unlikely to explain our salience results.

Furthermore, we examine how salience effects vary cross-sectionally by investor sophistication. Past research suggests that less sophisticated investors benefit more from financial disclosures than more sophisticated ones. Lawrence (2013) finds evidence that buy-and-hold individual investors benefit most from clear and concise disclosures, and Battalio et al. (2012) find that investors initiating small trades tend to ignore accruals information or trade in accruals of attention-grabbing stocks in the wrong direction.

Using Ali et al.’s (2008) measure of investor sophistication, we compare the difference in accruals discounting by SCF disclosers and SCF withholders between the subsample of more sophisticated investors versus the subsample of less sophisticated investors. Consistent with salience being more beneficial for less sophisticated investors, we find that the increased accrual discounting by SCF disclosers versus withholders is 2.25 times larger for the low sophistication group than for the high sophistication group. For low sophistication investors, the sum amount of accrual discounting over the earnings release date and 10-K/Q date is four times larger for SCF disclosers than for withholders.

We perform numerous additional robustness tests including use of an alternative portfolio-characteristics-adjusted returns measure; an extensive set of controls with fixed effects of firm, quarter, and industry; clustering standard errors by earnings announcement quarters; alternative accruals measuresFootnote 5; and examining a sample where accruals estimated from SCF are close in magnitude to accruals estimated from the balance sheet. Our results are generally robust to all these variations.

Finally, we address endogeneity of SCF disclosure as a remaining alternative explanation for our salience results. Despite our inclusion of extensive control variables, we may not have controlled sufficiently for fundamental differences between firms that choose to disclose SCF versus firms that choose to withhold. We employ multiple procedures to mitigate potential self-selection bias arising from the endogeneity of an SCF disclosure. First, we develop an empirical model for the determinants of a firm’s choice to disclose SCF in the earnings press release. We use determinants from past research and offer two new determinants—an indicator variable for whether the analysts provide cash flow forecasts, and an indicator variable for whether the firm discloses pro forma earnings. Using this selection model, we perform the Heckman (1979) analysis and the propensity-score-matching analysis. We find that the results are robust to both. We also repeat our analysis using a sample of firms that consistently disclosed SCF. While potential self-selection bias is not removed completely by this analysis, it is likely to be less severe. Our results continue to hold for this restricted subsample.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section discusses related literature on salience effects. Section 3 discusses sample and research design. Section 4 presents the results, and Sect. 5 discusses tests for robustness and endogeneity of the decision to disclose SCF. Section 6 concludes.

2 Background literature from psychology and salience effects

The psychology literature explains that, for information to be used, it must be first perceived and encoded as a mental representation in the brain before it is processed and understood (for example, see Fiske and Taylor 1991). Perception and encoding necessitate attention, which requires effort and must be selective as the amount of information available is vast (for example, Kahneman 1973). Therefore attention is more likely to be directed toward signals that are easy to access and process, so the salience and presentation format of information will affect how much and how well it is processed and used to value the firm.

Evidence from psychology indicates that salience effects are robust and widespread (Fiske and Taylor 1991). Indeed, the large volume of research on salience and attention effects in the advertising area within the marketing field is testament to the importance of salience and attention; as Sacharin (2000) writes, “Attention is a prerequisite for all marketing efforts.” With the availability of brain imaging devices, research on attention has also blossomed in the cognitive neuroscience field; see Posner (2011).

Experimental evidence in the accounting literature also provides strong evidence that salience affects how both naïve and professional readers incorporate the information (Hopkins 1996; Hirst and Hopkins 1998; Hopkins et al. 2000; Dietrich et al. 2001; Hewitt 2009). A growing literature in accounting and financial economics of archival studies also documents attention effects on the capital market (DellaVigna and Pollet 2009; Hirshleifer et al. 2009; Chakrabarty and Moulton 2012). Archival studies that focus specifically on the effects of salience on valuation are sparse (Klibanoff et al. 1998; Huang et al. 2015), though studies on recognition versus disclosure (Aboody 1996; Ahmed et al. 2006; Davis-Friday et al. 1999; Yu 2013) are related if recognition of accounting items on the face of the financial statements is interpreted as having higher salience than disclosure in footnotes of the financial statements. Finally, recent archival and experimental studies of disclosure readability related to format, data disaggregation and labelling, and disclosure attributes suggest that ease of processing affects investors’ reaction to financial information, with significantly stronger effects for small investors (You and Zhang 2009; Miller 2010; Rennekamp 2012; Huang et al. 2014). See Libby and Emett (2014) for a survey of the literature on presentation effects on managers and users.

As described in the introduction, we apply the predictions of Hirshleifer et al. (2011) and hypothesize that investors are more likely to discount accruals at the earnings announcement and less post-earnings announcement drift if accruals are more saliently disclosed at the earnings announcement. We use the disclosure of the statement of cash flows as an indicator of greater salience of accruals. This is because calculating accruals from the SCF requires investor to identify only two major items from the SCF and perform one subtraction, simply, net income minus cash flows from operating activities. In contrast, when the SCF is withheld, investors must identify all current asset and current liability items in the comparative years’ balance sheets, calculate changes of these items, separate operating from non-operating items, deduce depreciation using balance sheet footnotes and the income statement, and then perform a series of calculations to obtain accruals.Footnote 6

Fiske and Taylor (1991) indicate that vivid stimuli draw greater observer attention, and Song and Schwarz (2008) find evidence that tasks that are perceived to be easy are more likely to be performed. The greater salience and simplicity of obtaining accruals information from the statement of cash flows relative to the balance sheet suggest that investors are more likely to attend to accruals information.

These arguments collectively suggest the salience hypothesis prediction that investors are more likely to discount accruals for their lower persistence relative to cash flows when the SCF is additionally disclosed at the earnings announcement date compared with when only balance sheets are disclosed. In other words, we predict less mispricing of accruals for SCF disclosers than SCF withholders within the sample of firms that disclose balance sheets in the earnings press release.

3 Data and research design

3.1 Measuring availability of statement of cash flows at earnings announcements

Most studies examining investor response to disclosure of accruals in the earnings release use a hand-collected sample, which restricts their sample to relatively short periods. For example, Baber et al. (2006) examine a sample of 10,248 earnings announcements from the fourth quarter of 1992 to the third quarter of 1995. The sample of Louis et al. (2008) consists of 11,708 earnings announcement and spans 3 years from 1999 to 2002, while Levi’s (2008) sample covers only 1854 firm-quarters in 2001 and 2002.

Following D’Souza et al. (2010), we use the Compustat Quarterly Preliminary History database to identify whether the balance sheet and the statement of cash flows are provided at the earnings announcement. The database collects financial data items from various sources, including The Wall Street Journal, press releases, newswires, and 8-Ks, prior to when 10-Qs are filed with the S.E.C. The database provides coverage of more than 80 % of the Compustat universe since 1987, which allows us to examine a comprehensive large sample of unique firms over a longer period than is possible in prior studies using hand-collected disclosure information.

The Preliminary History database is necessary for our study because it identifies the accounting data items that are disclosed at the time of the earnings announcement and so are publicly available to investors at the earnings announcement before the actual filing of the official financial reports to the S.E.C. The regular Compustat database contains all data items from the actual filings of the official financial reports with the S.E.C., which usually occurs a few days to several weeks after the earnings announcement and so would be unsuitable to use to identify SCF disclosers at the earnings announcement.Footnote 7

To identify firms that provide balance sheet in earnings announcements, we require Total Assets (ATQ), Current Assets (ACTQ), Total Liabilities (LTQ), Current Liabilities (LCTQ), and Shareholder’s Equity (SEQQ) to be nonmissing in the database. To measure the availability of the statement of cash flows, we define an indicator variable, CF, which takes the value of one if Operating Activities – Net Cash Flow (OANCFQ) is provided in the earnings announcements and zero otherwise.Footnote 8 , Footnote 9

We use the statement of cash flow method to estimate accruals, so total accruals is calculated as income before extraordinary items minus cash flow from operations. Our main explanatory variable of interest R_TACC_MV is the decile rank measure of the quarterly total accruals divided by end of fiscal quarter market value of equity.Footnote 10 See “Appendix” for detailed definition.

3.2 Market reaction to earnings announcement

We test whether the market discounts accruals at the earnings announcement date using the regression model in Eq. (1) below.

We measure the market reaction using SARET2d, the size-adjusted returnsFootnote 11 compounded over the 2-day window (0, 1), where day 0 is the date of earnings announcement.Footnote 12 Our key test variable is R_TACC_MV.

Sloan (1996) finds that the accrual component is less persistent than the cash flow component of earnings, so firms reporting high accruals tend to have lower accounting profitability in the future periods. Therefore the accrual component of earnings should on average be discounted at the earnings announcement if the firm provides sufficient supplemental information for investors to reliably estimate accruals. Moreover, if investors can estimate accruals using balance sheets alone, then we should expect to observe similar magnitudes of discounting of the accruals, regardless of whether the statement of cash flows is also provided. However, if investors have limited attention and information processing power, an SCF disclosure increases salience of the accruals and reduces the cost of acquiring and processing the accrual information. Because the accrual component of earnings has lower persistence, we would then see heavier discounting of accruals at the earnings announcement if the SCF is disclosed in addition to the balance sheet than when SCF is withheld.

To estimate the impact of statement of cash flows, we estimate Eq. (1) separately for the CF = 0 and CF = 1 subsamples. Since all earnings announcements in our sample include a balance sheet, we can draw direct inference about the incremental usefulness of the statement of cash flows by testing the difference between the coefficients on R_TACC_MV for the two subsamples.

For control variables in the market reaction tests, we include the standard earnings surprise variable, R_SUE, measured as the rank decile of earnings surprise, which is estimated relative to the median analyst forecast when available or the seasonal random walk model of same quarter last year’s earnings when not.Footnote 13 We also control for revenue surprise R_SUS because Jegadeesh and Livnat (2006) find that investors react differently to the revenue and expense components of unexpected earnings. We include size-adjusted returns over the 5-day window immediately before earnings announcement SARET5d to control for investor sentiment on market reactions to earnings (Aboody et al. 2013). We also include earnings surprises from the previous quarter (LSUE) to capture the effect of post-earnings announcement drift. Finally, we control for common risk factors including size (logMV), market-to-book ratio (MTB), return volatility (RET_STD), and momentum (RET12m). Detailed definitions of these variables are provided in the “Appendix”.

3.3 Investor sophistication

Following Ali et al. (2008), we treat institutions holding medium stakes (1–5 % share ownership) in a firm as sophisticated investors who have the strongest incentive to acquire and trade on private information around earnings announcements. These investors are also more likely to pay attention to information disclosed publicly in the earnings announcement.Footnote 14 We measure the proportion of sophisticated traders using the ratio of shareholding by institutions with medium stakes divided by total shareholdings by investors who are likely to trade around earnings announcements.

In Eq. (2), INST_M is the percentage shareholdings by institutions that own 1–5 % of shares, and INST_H is percentage shareholding by institutions that own more than 5 % of shares. The denominator measures total ownership by investors who are likely to trade at earnings announcements. We use the ratio INST as our measure for investor sophistication.

If the disclosure of the statement of cash flows facilitates accurate pricing of accruals by increasing salience and lowering investor information acquisition costs, then its effect is most noticeable among firms that are widely held by less sophisticated investors, such as individuals or institutions with small holdings in the firm. Such investors are less attentive to financial statement information and so are less able to infer accrual information from balance sheets alone or find it prohibitively expensive to do so.

To investigate whether the usefulness of the SCF disclosure varies with the degree of sophistication of the firm’s investor clientele, we adopt a 2 × 2 research design and partition the full sample into four subsamples based on availability of statement of cash flows (CF = 0 or 1) and investor sophistication (INST above or below median). We then estimate regression (1) within each subsample and test the differences of β 1 within each investor sophistication group. If disclosure of the statement of cash flows at earnings announcements mainly benefits less sophisticated investors, we would expect to observe its marginal effect on accrual pricing to be significantly stronger for firms in the low investor sophistication group.

Our measure of investor sophistication using institutional holdings may also proxy for costs of arbitrage, such as price pressure and shorting cost. To more definitively attribute superior information processing abilities of sophisticated investors to explain the difference in how investors evaluate accruals between SCF disclosers and withholders, we do a further refinement to our test. We add an initial step before we perform the test described above. We first sort firms into quintiles using a different proxy for arbitrage costs than institutional holdings. We use idiosyncratic volatility (Mashruwala et al. 2006) and Amihud’s (2002) illiquidity measure. Within each quintile, we then sort by our institutional holdings variable, and the rest of the test proceeds as before.

3.4 Post-earnings announcement returns

Prior research finds empirical evidence that total accruals can be used as a reliable predictor of future returns, suggesting that the accrual information is not efficiently impounded into prices when it is publicly released (Sloan 1996; Cheng and Thomas 2006; Teoh and Zhang 2011). This research also attributes the mispricing of accruals to investors’ failure to understand the differential persistence of the accrual and cash components of earnings. Following this argument, Hirshleifer et al. (2011) derive a model of accrual misvaluation when investors with limited attention do not account for the differential persistence of the accrual versus cash flow components of earnings.

Hewitt (2009) provides evidence that experimental subjects make more accurate forecasts of earnings when the cash and accrual components of earnings are presented separately to them. Therefore we expect that a statement of cash flows where operating cash flow and accrual components are presented separately will help increase investors’ awareness of the differential persistence of these two earnings components. The resulting salience would cause investors to forecast future earnings more accurately and price the firms more efficiently. Therefore current quarter accruals would have no predictive power for future abnormal returns. We test this prediction using the regression model:

We estimate Eq. (3) separately for the CF = 0 and CF = 1 subsamples and expect stronger negative correlations between current quarter accruals and future earnings announcement returns when the statement of cash flows is withheld in the current quarter’s earnings press releases (CF = 0). In addition to R_TACC_MV, we also include all control variables discussed in Sect. 3.2 that are applicable to long window tests.

To facilitate comparison of the delay in discounting accruals between CF = 0 and CF = 1 subsamples, we also compare the magnitudes of β 1 in regressions using Eq. (3) above when the dependent variable is the 2-day returns at earnings announcement date, 2-day returns at the 10-K/Q filing date, and the long window returns from earnings announcement date to +251 trading days after the earnings announcement. The separate regressions are run for the overall sample and for the low and high sophistication subsamples as well.

4 Results

4.1 Sample

Our sample selection procedure is summarized in Table 1. We begin with all firm-quarters from the first quarter of 2000 to the second quarter of 2012 in the Compustat Preliminary History database.Footnote 15 We remove utility and financial companies from the sample because Compustat use a different financial statement format for these firms than for industrial companies. We next merge this sample with CRSP and Compustat quarterly file and drop the firm-quarters for which the earnings announcement dates are missing or more than 90 days after the fiscal quarter-end. For the remaining firm-quarters, we retrieve the 10-Q or 10-K filing dates from the S.E.C.’s EDGAR website (ftp://sec.gov/), using CIK as company ID. To ensure a sample where salient accrual information is obtained from SCF disclosure in the earnings release itself and not from the actual 10-K/Q filing, we remove observations where the firms filed their 10-K/Q reports on the same day or within five trading days of the earnings announcement.Footnote 16 This allows us to examine investor response to accruals separately at the earnings announcement date and at the 10 K/Q filing dates. Finally, to hold constant availability of accrual information in the earnings release, we remove all firm-quarters where the balance sheet is not provided in the earnings release, so that we can test the incremental effect of the SCF disclosure as discussed in Sect. 2.Footnote 17

The above procedure results in a sample of 68,803 quarterly earnings announcements from the first quarter of 2000 to the second quarter of 2012, representing 3942 unique firms. The sample size represents approximately more than sixfold increase over sample sizes of past studies on the market reaction to the availability of accruals from balance sheet disclosures at the earnings announcement. Depending on data availability, the final sample size varies for the different sets of empirical analyses.

4.2 Market reaction to accrual information during earnings announcement

Table 2 presents the results of our market reaction analysis during earnings announcement. When estimating Eq. (1), standard errors are clustered by calendar date of the earnings announcement to take into account cross-sectional correlation of residuals from potential missing market-wide factors for firm returns in the regressions.Footnote 18 The main variable of interest, R_TACC_MV, is the decile rank of price-scaled total accruals, which has been standardized to range between 0 and 1. Its coefficient represents the 2-day announcement return difference between the bottom accruals decile versus the top accruals decile.Footnote 19

The results indicate that among SCF disclosers, that is, the CF = 1 group, the coefficient on R_TACC_MV of −1.900 indicates that the market substantially discounts accruals by about 190 basis points, t = −8.74, for firms in the top accruals decile relative to the bottom accruals decile. In contrast, accruals discounting is weaker at about 52 basis points for the SCF withholders between the top and bottom deciles even though the t-statistics of −2.88 indicates it remains statistically significant at conventional levels. The difference in coefficient for the accruals variable between the SCF disclosers (CF = 1) versus the SCF withholders (CF = 0) is a statistically significant amount at −138 basis points, t = −4.95.Footnote 20 These results suggest that SCF is incrementally useful to investors for discounting accruals despite the availability of the balance sheet, consistent with the salience hypothesis.

4.2.1 The role of differences in persistence

We checked whether the greater discounting of accruals in the CF = 1 subsample than in the CF = 0 subsample may be explained instead by a fundamental difference in the type of accruals and cash flows in the two subsamples. In other words, is the difference in earnings persistence attributable to accruals versus cash flows larger for CF = 1 than CF = 0 subgroups? Table 3 shows the opposite to be the case.

In Table 3, we regress quarter t + 1 earnings on quarter t accruals and cash flows, all variables scaled by lagged total assets, separately for CF = 0 and CF = 1 subsamples. The estimated coefficients are 0.463 for accruals and 0.765 for cash flows in the CF = 0 regression and 0.407 for accruals and 0.558 for cash flows in the CF = 1 regression. The difference between the cash flow and accrual coefficients of 0.302 for CF = 0 subsample is twice the difference in coefficients of 0.151 for CF = 1 subsample. In untabulated tests, we also examine regressions of quarter t + 4 earnings on accruals and cash flows, and the estimated coefficients are 0.376 for accruals and 0.717 for cash flows in the CF = 0 regression and 0.339 for accruals and 0.528 for cash flows in the CF = 1 regression. Again, the difference between accruals and cash flows coefficients are significantly larger for CF = 0 than CF = 1 regressions.Footnote 21

The larger difference in persistence of accruals relative to cash flows for CF = 0 should have resulted in stronger discounting of the accruals relative to cash flows in a world with fully attentive rational investors. Therefore our previous Table 2 evidence that accruals are discounted less for CF = 0 than CF = 1 firms cannot be explained by the difference in accrual persistence between the two groups. Instead, the evidence is consistent with the salience hypothesis.

4.2.2 The role of investor sophistication

The results in Sect. 4.2 show that investors discount accruals more when accruals are easily available with the SCF disclosure. In this section, we provide results on how benefits from salience of disclosure vary with investor sophistication. We partition the full sample into two subsamples based on INST, our measure for investor sophistication, and estimate the incremental effect of SCF disclosure separately for the two investor sophistication subgroups. As reported in the columns of Table 4, the effect of SCF disclosure on the markets’ reaction to accruals varies dramatically with the level of investor sophistication.

The first two columns of Table 4 Panel A present results for the low sophistication group and show that these investors do not discount accruals at the earnings announcement when SCF is withheld. The coefficient for R_TACC_MV is close to zero and not statistically significant, consistent with overpricing of accruals. On the other hand, when SCF is disclosed, even low sophistication investors discount the accruals by an economically and statistically significant amount of 175.8 basis points, t = − 4.93. The difference in coefficient magnitudes between CF = 0 and CF = 1 subsamples is statistically significant.

In contrast, for the high investor sophistication group in the last two columns of Table 4 Panel A, accruals are discounted whether SCF is withheld or disclosed, by 126.7 basis points and 202.4 basis points respectively. The difference in accrual coefficient between CF = 0 and CF = 1 groups is −75.7 basis points, indicating that accrual discounting remains significantly larger for the disclosers than the withholders, consistent with greater salience of accrual information for the disclosers even for the sophisticated group. Furthermore, in unreported tests, we find that the difference in accrual versus cash-flow persistence between CF = 0 and CF = 1 does not vary by institutional holdings group. Therefore differences in persistence do not explain Table 4 Panel A results, but differences in salience do. Salience differences between CF = 0 and CF = 1 are larger for firms with low institutional ownership, and accrual mispricing between CF = 0 and CF = 1 is correspondingly larger for these less sophisticated investors.

The easier availability of accrual information from the SCF disclosure helps low sophistication investors to largely overcome their difficulty with processing accruals. This can be seen from comparing accrual coefficients for CF = 1 firms between the low and high sophistication subsamples. The coefficient for the low sophistication group is comparable to that for the high sophistication group, −1.758 versus −2.024. Together, these results suggest that providing SCF in the earnings announcement improves salience of accruals for all types of investor sophistication, but the least sophisticated investors reap the most benefit from increased salience.

Since institutional holdings may also proxy for arbitrage costs, Table 4 Panel B provides evidence for a test that attempts to refine away arbitrage costs. The high- versus low-institutional-holdings subsamples are classified within each arbitrage-costs quintile group, using either idiosyncratic volatility or the Amihud illiquidity measure to proxy for arbitrage costs. The panel presents only the key results for accruals, and the test statistics for the difference in accrual coefficients. The earlier results remain robust. The low institutional-holdings group fails to discount accruals when SCF is withheld but not when disclosed, whereas the high institutional-holdings group discounts accruals for both disclosers and withholders, albeit with higher discounting for disclosers than withholders. In summary, Table 4 evidence is consistent with superior information processing abilities or greater attentiveness of sophisticated investors driving the difference in stock return response to accruals between SCF withholders and disclosers.

4.3 Current accruals as a predictor of post-earnings announcement returns

Table 2 regressions examine whether investors discount accruals differently between SCF disclosers versus SCF withholders at the earnings announcement date. If accruals were discounted sufficiently at earnings announcement, there would be no relation between accruals and the subsequent longer-period returns post-earnings announcement. On the other hand, if accruals were insufficiently discounted so accruals are overpriced at the earnings announcement date, accruals will continue to be negatively related to the longer-period abnormal returns post-announcement.

Table 5 Panel A presents the results of estimating Eq. (3) for the accrual salience effect on the continuously compounded returns over 250 trading days after earnings announcement, corresponding to approximately a 12-month period.Footnote 22 The accrual coefficient is significantly negative for both groups, suggesting that there is insufficient discounting of accruals and hence overpricing of accruals at the earnings announcement date for both SCF disclosers and withholders. However, the overpricing is significantly larger for the withholders than the disclosers; the R_TACC_MV coefficient is −15.677 for CF = 0 compared with −8.465 for CF = 1, and the difference, 7.211, is statistically significant with a t-statistic of 2.95. These results provide strong support that salience of disclosure affects the ability of investors to use accrual information efficiently.Footnote 23

4.4 Filing date reaction and comparison of speed of accrual discounting

If the SCF were withheld at earnings announcement, it would be available to investors when reported to the S.E.C. on the 10-K/Q filing date. Therefore we consider whether investors discount accruals at the filing date more for CF = 0 than CF = 1 subsamples to catch up for insufficient discounting of accruals at the earlier earnings announcement date. Table 5 Panel B presents the coefficients of R_TACC_MV for regression Eq. (3) using the 2-day returns at filing dates as the dependent variable. To facilitate comparisons about the timing and total amount of accrual discounting between CF = 0 and CF = 1 subsamples, Panel B also presents results for R_TACC_MV coefficients in regression Eq. (3) when the dependent variables are the 2-day earnings announcement date returns (0, 1), the returns over the period between earnings announcement and 10-Q filing, and the long-window (0, 251) returns from the earnings announcement date.Footnote 24 The regressions are performed separately for the overall sample and for low and high investor sophistication groups separately.

The first row of Table 5 Panel B summarizes earlier results for the earnings announcement for the full sample and the low- and high-sophistication subsamples. The results from the filing day returns in the next row in Table 5 Panel B show that the discounting of accruals is greater for the high institutional-holding firms relative to the low institutional-holding firms, consistent with the findings of Balsam et al. (2002). In addition, investors react significantly to accruals when the information becomes available from the SCF disclosure at the filing date for CF = 0 firms in the full sample and in both the low- and high-sophistication subsamples. Thus, even for the high sophistication group, there is further catch up on accrual discounting when SCF becomes available at the filing date. For CF = 1, the low sophistication investors ignore the further release of SCF at filing date, whereas high sophistication investors continue to react to accruals at filing date.

In the low sophistication group, the accrual coefficient is −1.931 at earnings announcement date for CF = 1 versus only −0.470 at filing date for CF = 0, a fourfold difference. A similar comparison for the high sophistication group also shows a 2.8 (=−1.950/−0.685), in absolute value, times larger accrual coefficient for SCF disclosure at the earnings announcement than at the filing date. Furthermore, the combined earnings announcement and filing dates accrual effect is twice as large for CF = 1 than for CF = 0 in the full sample, and the difference is mainly from the low sophistication group, where the absolute accruals coefficient is more than three times (=−2.004/−0.573) larger for CF = 1 than for CF = 0. Thus, all else equal, earnings announcements are more salient to investors than 10-K/Q filings, and SCF disclosure at 10-K/Q filing would not be a good substitute for SCF disclosure at the earnings announcement date for efficient pricing of accruals. This result is consistent with past studies finding a smaller investor reaction at the filing date than at the earnings announcement date (Louis et al. 2008; Levi 2008).

The smaller amount of accrual discounting at the earnings announcement for CF = 0 is not coming from a relatively higher persistence of accruals for CF = 0 than for CF = 1. Assuming that accrual mispricing is corrected within 12 months, we can use the absolute accrual coefficient for the long window (0, +251) returns to estimate the amount of correct discounting for accruals. The absolute accrual coefficient for this window is actually larger for CF = 0 than CF = 1 within the full sample and within the high sophistication subsample. Comparing between CF = 0 and CF = 1 subgroups, the accrual coefficient is 1.6 (=−16.245/−10.397) times larger within the full sample, slightly larger (1.2 = −16.701/−13.680) within the low sophistication group, and almost double (=−15.361/−7.746) within the high sophistication group. Thus a larger fraction of the total amount of accrual discounting occurs at the earnings announcement date when SCF is disclosed than when it is withheld; 18.58 % in the full sample, 14.12 % in the low sophistication group, and 25.17 % in the high sophistication group. This pattern of earlier discounting of accruals remains even considering accrual discounting at both earnings announcement and filing dates. The overall smaller accrual anomaly and earlier discounting of accruals for CF = 1 indicate that SCF disclosure increases the salience of accruals and improves their efficient pricing.

4.5 Period analysis of the accrual anomaly

Green, Hand, and Soliman (2011) report that the magnitude of the accrual anomaly has declined from around 2000 to 2009. We divide our sample period into two subperiods from 2001 to 2006 and 2006 to 2012 and re-run regression (3) for the subperiods. Consistent with the results of Green et al. (2011), the negative accrual coefficient declined in absolute value, changing from −14.30 (t = −7.68) to −9.58 (t = 3.83) for the full sample.Footnote 25

Interestingly, when we separately examine the CF = 0 and CF = 1 subsamples, we find that the decline occurs only in the CF = 1 subsample. The accrual coefficient is −10.12 % (t = −5.05) in the earlier subperiod and −3.11 % (t = −0.99) in the later subperiod. The CF = 0 subsample exhibits similar accrual anomaly magnitude in both subperiods, −15.04 % (t = −6.38) and −14.05 % (t = −3.99), respectively. This suggests that SCF disclosure is another factor in reducing the accrual anomaly. When SCF is absent in the earnings press release, accruals are not salient to investors at the announcement. As Sect. 4.4 analysis above documents, the investors do not make up for the lack of response to accruals at the later filing date when the SCF information is made available, so the accrual anomaly persists.

4.6 Current accruals as a predictor of analyst forecast errors

Long-window abnormal returns are notoriously difficult to estimate, and a common concern with mispricing tests is that risk factors have not been adequately controlled for when estimating abnormal returns. To corroborate the returns test, we examine whether another group of stakeholders, financial analysts following the firm, are also subject to salience effects. Bradshaw et al. (2001) and Teoh and Wong (2002) find that analysts are credulous with respect to accruals.

In Table 6, we replace post-announcement abnormal returns with consensus analyst forecast errors of quarter t + 1 earnings surveyed in the month after announcement of quarter t earnings, using standard controls from the literature. The results show that forecast errors are significantly negatively correlated with accruals only for the CF = 0 sample, and the difference in predictability between the two subsamples is marginally significant. These results corroborate that the returns tests results are not primarily driven by poor risk estimations. Relevantly here, the results suggest that even expert financial statement users such as financial analysts benefit from increased salience of accruals with a SCF disclosure in earnings releases. They provide support for the call by NIRI, the CFA Institute, and the S.E.C.’s Pozen Committee for firms to provide SCF in earnings releases.

5 Robustness tests

5.1 Accruals estimation error using the balance-sheet approach

Past research suggests that accruals estimated from the SCF are more accurate than those estimated using the balance sheet (Hribar and Collins 2002). We perform several robustness tests to address differences in accrual estimation errors between the balance sheet and SCF methods. First, we repeat the returns tests of Tables 2 and 5 but now using accruals estimated from the balance sheet instead of the SCF. The weaker accrual discounting in Table 2 and stronger return reversals in Table 5 may have resulted from greater estimation errors for accruals obtained using balance sheet for CF = 0 when the SCF is unavailable.

The evidence in Table 7 Panel A suggests that this is not the case.Footnote 26 Similar statistically significant evidence of weaker accrual discounting at the announcement date and stronger predictability of post-announcement returns reversals for accruals are observed for CF = 0 than for CF = 1 subsamples. The differences in balance sheet estimated accrual coefficients, −1.186 and 5.802, are of similar magnitudes to those in Tables 2 and 5, respectively, using SCF estimated accruals.

Second, we construct a “clean” sample by including only observations for which the accruals estimated from the balance sheet are within 90 % of the accruals estimated from the cash flow statement. The balance sheet accrual is estimated using the equation: Accruals = ΔCurrent Assets (ACTQ) − ΔCash (CHEQ) − ΔCurrent Liabilities (LCTQ) + ΔDebt in Current Liabilities (DLCQ).Footnote 27 The statement of cash flow accrual is calculated as Accruals = Earnings (IBQ) − Operating Cash Flow (OANCFQ) + Depreciation (DPQ). To ensure that all balance sheet items required for estimating accruals are available to investors, we further constrain the sample to include firms for which ACTQ, CHEQ, LCTQ, and DLCQ are provided in earnings announcements and exclude Depreciation Expense (DPQ) from calculation of accruals because many firms in our sample do not disclose this information in their earnings press release.Footnote 28

The selection of observations for the clean sample is overly restrictive because fully attentive investors can use information in the income statement or other sections of SCF to reconcile even moderate differences in accruals estimated from the balance sheet approach or from the SCF, such as for example, asset write-downs and cash-based acquisitions of other companies. By ignoring this possibility, the clean sample test therefore sets a higher hurdle than necessary for testing differential salience of accruals between disclosers and nondisclosers. Nevertheless, if the clean sample test yields statistically significant evidence of higher accrual salience for disclosers than nondisclosers despite the higher hurdle, readers can be confident of the robustness of the salience result.

We rerun our earlier tests using this sample, and as reported in Table 7 Panels B, all previous results are shown to be robust. These results confirm that it is disclosure salience, and not error in accruals estimation, that explains accruals mispricing.

In our final set of analyses, we examine whether our results can be explained by the difference in perceived credibility of balance sheet and SCF accruals. For example, if investors perceive balance sheet accruals as systematically unreliable, they may fail to adequately discount accruals when SCF is absent. To examine whether this is the case for CF = 0 subsample, we estimate perceived reliability using correlation of balance sheet accruals and SCF accruals over the prior 20 (minimum eight) quarters and divide the sample into low versus high correlation groups. Then, we rerun the market-reaction and post-announcement return regressions separately within the two subgroups. Untabulated results show little difference in accruals mispricing between low and high perceived accrual-reliability subgroups.

5.2 Correcting self-selection bias and potential additional information in SCF

Cash flow disclosure in the earnings press release is voluntary. Prior studies find that firms disclosing supplemental balance sheet or cash flow information in earnings announcements differ systematically from nondisclosers. For example, Chen et al. (2002) find that disclosing balance sheet information is more popular among firms that are younger, operate in high-tech industries, report losses, have larger forecast errors, engage in mergers or acquisitions, or have more volatile stock returns. Levi (2008) finds that firms providing accrual information in earnings press releases have lower quality accruals than those deferring the disclosure of accruals to 10-Q filings. D’Souza et al. (2010) find that firms disclose the SCF when their operating cycle is shorter and when balance sheet accruals contain more measurement errors. We use multiple procedures to control for the potential endogeneity of an SCF disclosure and include instruments for potential additional information available only from SCF disclosure in our sample of earnings announcements that disclose the balance sheet.

5.2.1 Heckman Model

First, we employ the standard Heckman (1979) two-stage method. The probit regression model for a firm’s choice to additionally disclose the SCF in the earnings release is as follows:

Firms that disclose the SCF in earnings press releases may also provide other information, such as more detailed financial statements or pro forma earnings metrics that are relevant for investors to correctly price the accrual component of reported earnings. We include three variables in Eq. (4) to control for the availability of additional value-relevant information. We follow D’Souza et al. (2010) and use two disclosure ratio variables, DR_BS and DR_IS, to capture the number of balance sheet and income statement items disclosed at earnings announcements. The third determinant is a binary variable, PROFORMA, to indicate whether pro forma earnings are disclosed at earnings announcements.

We include operating cycle, OC, earnings volatility, EARN_VOL, operating cash flow volatility, CFO_VOL, and a Big 4 auditor dummy BIG4 to control for the quality of reported accruals. To capture investors and financial analysts’ general demand for information, we include the number of analysts following the firm, NUMEST, and percentage of shares owned by sophisticated institutional investors, ADJPIH. We also include a binary variable, FCPS, to indicate whether there are outstanding analyst cash flow forecasts for the current firm-quarter. DeFond and Hung (2003) find that analysts issue cash flow forecasts when they consider operating cash flow a more useful measure of firm performance and when they perceive accruals to have low quality. We expect managers to cater to analysts’ demand by providing SCF disclosure in the earnings release. FCPS also controls for the potential impact of analyst cash flow forecast on accrual mispricing, given recent studies’ finding that the accrual anomaly tends to be weaker for firms with both earnings and cash flow forecasts issued by analysts (Mohanram 2014; Radhakrishnan and Wu 2014).

We also include several additional variables that prior research finds are important determinants for managers’ decision to provide the balance sheet in the earnings releases (Chen et al. 2002; Louis et al. 2008), even though we restrict our sample to all firms that disclose the balance sheet at the earnings announcement. These include an indicator variable, LOSS, for firms reporting a loss and controls for information uncertainty using stock-return volatility, RET_STD, firm age, AGE, and an indicator variable for firms operating in the high-tech industry, HT, and another indicator variable for firms that engage in mergers and acquisition during the current quarter, ACQ. We also include firm size, LogMV, market-to-book, MTB, and financial leverage, LEV, as controls for risk. In addition to the firm characteristics discussed above, we also control for industry and quarter fixed effects in the regression.Footnote 29 Detailed definitions of variables are provided in the “Appendix”.

Our analysis of a firm’s choice to disclose SCF in the earnings announcement is presented in Table 8. These results are based on a sample of 58,261 earnings announcements, of which 19,719 (34 %) include an SCF and 38,542 (66 %) do not. Panel A of Table 8 presents the descriptive statistics of the sample. We can see that the disclosers differ significantly from the withholders across all firm characteristics examined, suggesting that it is important to control for the self-selection bias in the subsequent analyses of the salience effect of SCF disclosures. The probit regression result largely confirms this observation.

As shown in Panel B of Table 8, with the exception of EARN_VOL and ACQ, which are insignificant, and PROFORMA and BIG4, which are marginally significant at 10 %, all variables have highly significant marginal effects on the firm’s decision to disclose SCF in the earnings announcement. In particular, firms that disclose SCF also tend to provide more detailed balance sheet and income statement at earnings announcements. In contrast, firms that withhold SCF information tend to have higher operational uncertainty (in the high-tech industry and have high cash flow volatility and high return volatility) and larger accruals (long operating cycle, reporting loss). In addition, firms that are widely held by institutional investors and have analyst cash-flow forecasts are more likely to disclose the SCF, reflecting that managers cater to the demand for accrual information from investors and analysts. The high McFadden’s R2 (0.261) for the probit regression suggests that the empirical model for the voluntary choice to disclose SCF is reasonably well-specified.Footnote 30

Our tests examine whether managers behave strategically with regard to SCF disclosure, and therefore, as a design choice, we exclude instruments related to managerial strategic incentives to disclose SCF in the first-stage probit model. In an untabulated test that includes the decile rank of accruals, an indicator variable for anticipated equity issuance, and an interaction variable between these two variables in the probit model, we find that the decile rank of accruals is incrementally highly significant. The new issue indicator is borderline significant and the interaction term has the same negative sign but not significant at conventional levels. This evidence, combined with the earlier evidence of smaller stock return discounting of accruals for SCF withholders, suggests that firms strategically withhold the SCF to achieve short-term stock price boosts when they report high accruals or are about to issue new equity.

Moving to stage 2 analysis of the Heckman model, Table 9 presents results that are qualitatively similar to those reported earlier in Tables 2 to 5. In particular, both the market-reaction and future-return test show that accruals are priced more efficiently by the market when the SCF is disclosed, and these salience effects are stronger for firms widely held by individual investors.

5.2.2 Propensity-Score Matching Model

Our second approach to control for endogeneity is based on the propensity-score matching (PSM) method. We first calculate the propensity score for disclosing the SCF in earnings press releases from the regression in model (4). For each CF = 1 firm-quarter, we find a CF = 0 firm-quarter that has the closest propensity score.Footnote 31

We then repeat our regression analyses using the PSM sample, and the results are reported in Table 10. We can see that, while the statistical significance of some of the coefficients becomes weaker due to the markedly reduced sample size and hence power, the tenor of our results that SCF disclosure enables investors to more efficiently price accruals information remains unchanged.

We note that our result is unlikely to stem from an observed increased SCF disclosure and a declining strength of the accruals anomaly over our sample period (Green et al. 2011). The relative proportion of SCF disclosers to withholders is evenly distributed in the PSM sample, averaging at 1:1 over our sample period and with little variation across quarters. The inclusion of quarter fixed effects in the first-stage prediction model appears to have effectively removed the time trend of SCF disclosure from the PSM sample. Therefore any relation between SCF disclosure and accruals mispricing for the PSM sample cannot be attributed to the general temporal changes in the accrual anomaly.

5.2.3 Consistent Disclosure Policy Sample Test

While the Heckman model and the PSM analysis are commonly used methods for correcting endogeneity bias, they have shortcomings. For example, successful applications of these methods depend on high quality instruments in the first-stage probit model that are exogenous to the selection decision (Larcker and Rusticus 2010). Such instruments, however, are hard to come by in empirical accounting research. Therefore, as a further test, we use a model-free approach to control for endogeneity on our results next. This approach is motivated by the observation that most firms follow a stable SCF disclosure policy, possibly because switching frequently is costly to the firm and the manager. Therefore, once a firm decides to provide or withhold the SCF in the earnings press release, it tends to follow the same policy in subsequent quarters. In other words, a firm has only limited discretion in SCF disclosure, especially in the quarters following the quarter in which the firm changed its policy. Based on this observation, we construct a sample largely free of endogeneity bias by excluding firms that change their SCF disclosure policy more than once during the past quarterly earnings announcements. In addition, for firms that change only once, we exclude the switch quarter from our sample. As shown in Table 11, the results from this sample of consistent disclosers or withholders are largely the same as the results from the full sample, and none of our inferences change.Footnote 32

In summary, our analysis in this section shows that the mitigated accrual mispricing for SCF disclosers is due to the availability of SCF information per se, rather than other firm characteristics that drive the firm’s decision to disclose SCF in earnings press releases. This evidence provides further support for the hypothesis of the salience effect of SCF disclosure.

6 Conclusion

Current disclosure rules in the U.S. do not require companies to provide complete financial statements in quarterly earnings releases. As a result, the quantity and quality of supplemental accounting information disclosed at earnings announcements vary significantly across firms. In recent years, while the great majority of companies include a balance sheet in their earnings releases, relatively few of them additionally provide the statement of cash flows. This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the effect of statement of cash flows disclosure on the market’s ability to efficiently price the accrual component of reported earnings.

We examine several aspects of the capital market consequence of disclosing statement of cash flows in the earnings announcements, including the immediate market reaction to accruals, comparison of the immediate market reaction to accruals by investor sophistication, and the predictive power of accruals for post-earnings announcement abnormal returns. We find consistent evidence that an SCF disclosure increases the salience of the accrual information and so helps less sophisticated investors incorporate accrual information to value the firm more accurately, thereby improving the overall efficiency of the market’s pricing of accrual information.

Our empirical analyses are all specifically designed to capture the effect of the salience of disclosure rather than the availability of information. Our results therefore lend direct support to the importance of salience, and therefore format of disclosure, and not just the content of disclosure for capital market valuation of accounting information when investors have limited attention.

Our study contributes to the corporate disclosure literature by providing the first comprehensive analysis of the capital market consequence of the incremental effect of disclosing the statement of cash flows in earnings announcements in addition to the balance sheet. Our results that investors use accrual information more efficiently when accrual information is provided by both the statement of cash flows and the balance sheet than by the balance sheet alone suggest the importance of salience and ease of processing of accounting information for market efficiency. We provide evidence of the benefits of heeding recent calls from NIRI, CFA Institute, and the S.E.C.’s Pozen Committee to provide the statement of cash flows in earnings releases. Our results are consistent with the argument that disclosure of the statement of cash flows in earnings announcements reduces information acquisition costs and increases the salience of accruals and creates a more level playing field for all market participants. Finally, regulators need to consider not just content but also format of presentation when evaluating disclosure requirements because format affects salience and ease of processing and ultimately the efficiency with which the market uses the information.

Notes

For comparison of the change in the frequency of disclosure of balance sheet and SCF items in the earnings announcement, D’Souza et al. (2010) report that, during their sample period of 2000–2003, 79.4 % of earnings announcements contain balance sheet items, while only 14.5 % contain SCF items. As of the second quarter of 2012 in our database, about 90 % of firms disclose balance sheet items, and about 50 % disclose SCF items.

For example, Hirshleifer and Teoh (2003) model equilibrium pricing of accounting information when investors have limited attention. Lim and Teoh (2010) offer a simple model of limited attention and investors’ reaction to accounting information and review the literature on limited attention and salience effects in the capital markets.

SCF disclosure may have the opposite effect of distracting investors if more information increases cognitive burden, causes sensory overload, or both (Hirshleifer et al. (2009)). If the additional SCF statement is distracting to investors, then the stock return response to earnings news would be more muted, and the post-earnings announcement drift would be larger for firms that disclose SCF at the earnings announcement. Our results are consistent with SCF disclosure increasing salience of accruals, rather than distracting investor attention.

Hribar and Collins (2002) find that accruals estimated from balance sheet are less accurate than those estimated from the SCF. While higher accrual estimation error may contribute to less discounting of accruals at the earnings announcement date, it would not explain the difference in cumulative discounting of accruals by the time of the filing date. Nevertheless, we perform robustness checks on all of our tests using (1) a restrictive sample where the accruals values are similar between the balance sheet and cash flow statement estimation methods and (2) the full sample replacing SCF accruals with balance sheet accruals. The results are robust. See Sect. 5.1 and Table 7.

Teachers of financial accounting can attest to how students struggle to understand and calculate accruals from the balance sheet.

The Compustat Quarterly Preliminary History database is distinct from the usual Compustat Database and must be purchased separately. Subscribers to the current Compustat database cannot view historical preliminary data because it is overwritten by finalized data from 10-Q reports when they are filed with the SEC.

We did a manual check of a random sample of 50 earnings announcements from 2011 for the accuracy of our identification procedure. We find that the Compustat Preliminary History database correctly identifies SCF disclosure for 49 of these 50 announcements. D’Souza et al. (2010) also checked the accuracy of this identification procedure. Their manual check of a random sample of 699 earnings announcements shows that more than 90 % were correctly identified using the Preliminary History database, so they conclude that data quality is not an issue (p. 183, footnote 7).

Some firms provide only annual SCF in their Q4 earnings releases. While it requires only simple calculations for investors to derive quarterly cash flow from annual figures, we have nonetheless verified that our results are robust to using only Q1–Q3 earnings announcements.

It is more common in accrual anomaly studies to scale total accruals by total assets; see Hirshleifer et al. (2012). We use the market value deflator for the accrual variable to maintain consistency with the deflator for the earnings news variable R_SUE so that R_TACC_MV can be viewed directly as a component of the R_SUE variable. This allows us to directly compare the signs and magnitudes of the coefficients between these two variables to infer whether investors are attending to and therefore incorporating the differential persistence of the accruals versus cash flow components of the earnings news. In addition to price-deflated accruals, we also replicated our analysis using the percent accruals definition proposed by Hafzalla et al. (2011) and obtained qualitatively similar results.

Our results are robust to more sophisticated risk-adjustment methods such as the four-factor portfolio adjusted returns of Daniel et al. (1997).

Earnings announcement data are from Compustat, which provides the date, but not time, of the announcements. Berkman and Truong (2009) report that the fraction of firms releasing earnings after hours increased by 40 %, and market reactions to after-hours earnings announcements are captured on day +1. Therefore we include day +1 to capture market reactions to announcements that are made after the market closed. We also replicate all analyses using a three-day window (−1, 1) to incorporate potential information leakage on day −1 and obtain similar results.

Our results are robust to using a more restrictive sample of firms where earnings surprise is estimated relative to analyst forecasts only.

Ali et al. (2008) argue that institutions holding small stakes (<1 %) will not have sufficient incentive to acquire costly private information, while institutions holding large stakes (>5 %) usually have long-term strategic considerations and do not trade on short-term earnings. Therefore these two types of institutions will not have the same incentives as institutions holding medium stakes (1–5 %) to react to disclosed information in the earnings release.

We start our sample period in 2000 to avoid the data quality issues associated with pre-2000 data in the Preliminary History database (D’Souza et al. 2010).

Our results are robust and stronger without the five-day restriction between earnings announcement and 10 K/Q dates because of the greater number of observations.

We randomly selected 50 earnings releases with balance sheets from our sample and find 47 of them contain two periods of balance sheet information. Also note that all previous period balance sheet information is publicly available by the time of current quarter’s earnings announcement. Therefore fully attentive investors can access past financials from public sources even if they are not contained in the current earnings release itself.

Our results are robust to two-way clustering of standard errors by firm and earnings announcement date.

All observations are jointly ranked every quarter so the accruals decile cut-offs are the same between the CF = 0 and CF = 1 subsamples. We have roughly similar distributions of the number of observations across deciles in the two subsamples so any difference in coefficients in the two groups are not due to a difference in the range of accruals.

To obtain the t-statistic for the difference in accrual coefficients between CF = 0 and CF = 1, we run a pooled regression with all observations from the two subsamples and interact all independent variables with the CF = 1 indicator variable.

Though our focus is on the differential persistence between accruals and cash flows, it is interesting that overall earnings persistence is lower for CF = 1 than CF = 0. This suggests that managers voluntarily disclose SCF when earnings persistence is low and especially when cash flow persistence is low. This is likely because of increased investor demand for cash flow information when earnings have low persistence.

In unreported robustness tests, we use the sum of the four quarterly 2-day earnings announcement returns over the following four quarters as the dependent variable in regression Eq. (3) and obtain qualitatively similar results. This specification assumes that price corrections occur mostly at earnings announcement dates in the subsequent four quarters (Cheng and Thomas 2006). We also use the Daniel et al. (1997) portfolio four-factor adjusted returns as the dependent variable, and the results are also robust. Finally, we include firm fixed effects in Tables 2 and 5 regressions, and again the results are robust.

We also perform the Mishkin (1983) test to compare the rationality of accrual pricing between CF = 0 and CF = 1 subsamples. The forecasting equation for the same quarter next year earnings is EARNt+4 = γ0 + γ1TACCt + γ2CFOt, and the pricing equation is EARETt+4 = β(EARNt+4 − α0 − α1TACCt − α 2CFOt), where EARETt+4 is the quarter t + 4 earnings announcement return. We find that the coefficient on TACC in the pricing equation (α1) is significantly larger than in the forecasting equation (γ1) only in the CF = 0 sample, whereas the two coefficients are not statistically different in the CF = 1 sample. In other words, investors perceive accruals to have much higher persistence for future earnings than they do, so investors significantly overprice accruals when the SCF is withheld but not when it is disclosed. Therefore the Mishkin test results are consistent with the salience effect of SCF disclosure at the earnings announcement.

The coefficients at earnings announcement dates are similar to those reported in Tables 2 and 5 Panel A, with minor differences resulting from a slightly different set of control variables between Eqs. (1) and (3). To facilitate comparing coefficients, we use the same set of control variables as in Eq. (3) for all regressions in Table 5 Panel B. The coefficients for the long window also differ between Table 5 Panels A and B because Panel B returns are inclusive of earnings announcement date returns.

Including year 2000 weakens the accrual anomaly for the earlier subperiod, likely from anomalous 2001 returns.

For all robustness tests only the accruals coefficients are reported for brevity.

Compustat mnemonics are in brackets.

In unreported analysis, we find the availability of depreciation information have no significant impact on market reaction to accruals for firms that provide only the balance sheet in the earnings release. This is consistent with prior research’s finding that investors tend to use depreciation information inefficiently (e.g., Miranda-Lopez and Nichols 2012).

Industry fixed effects are defined using the Fama–French 12 industry classification. Quarter fixed effects are intended to capture any special economic shocks in a particular quarter or time variations in the demand, supply and precision of financial statement information. For example, Bronson et al. (2011) report that lower reliability of preliminary earnings in recent years. Audits have become longer because of new requirements by the PCAOB, but firms have maintained the same preliminary earnings release dates and audits may be incomplete before the earnings release. Quarter fixed effects are stronger controls than a simple time-trend variable.

We have included an extensive set of plausible factors that affect the choice to disclose SCF. As with all empirical tests, it is often challenging to include instruments for all conceivable endogeneity factors. We caution that the second-stage results will rely on our ability to control sufficiently for the self-selection of SCF disclosure. We also emphasize that controls for endogenous voluntary disclosure of the SCF are less relevant for the post-earnings announcement returns tests. This is because the long-window tests cumulate returns after the mandated 10-K/Q information is reported.

Matching was done with replacement and with no restriction on the maximum difference in propensity scores between treatment and control firms. The matching appears successful as the mean absolute difference in propensity scores between treatment and control is 0.006 %, and the 99 percentile is 0.06 %. We include quarter fixed effects in the first-stage probit model, so matching within the same quarter is unnecessary. However, our PSM results are robust to imposing this additional requirement.

Results are also robust to further restricting consistency sample to those with 20 (minimum of eight) quarters of earnings releases, so neither changes in sample composition or disclosure policy drive our results.

References