Abstract

We condition security price reactions to quarterly earnings announcements on whether firms disclose supplementary balance sheet and/or cashflow information that can be used to estimate the consequences of earnings management. Disclosure of supplementary information is voluntary, and thus, we consider the possibility that firms that disclose balance sheet and/or cashflow information differ systematically from firms that do not disclose. Results indicate that investors discount evidence of earnings management at the disclosure date when supplementary information is disclosed. Such results indicate more informed earnings interpretations of quarterly earnings when firms provide balance sheet and/or cashflow information concurrently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1. Introduction

This study uses security price reactions to quarterly earnings announcements to inform policymakers who are concerned about whether investors are misled by earnings management (hereafter EM). Following DeFond and Park (2001), we consider whether evidence of EM influences interpretations of earnings at the time of earnings announcement when details about the composition of earnings are not required to be disclosed. This aspect of the study distinguishes the study from prior studies that consider EM over longer event windows (Sloan, 1996; Subramanyam, 1996; Xie, 2001) or consider EM when details about earnings are required to be filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (Balsam, Bartov, & Marquardt, 2002).

We then investigate how interpretations of earnings at the time of the disclosure depend on whether firms voluntarily and concurrently disclose information beyond earnings that can be used to estimate and disentangle the consequences of EM. This investigation provides a basis for assessing whether investors are misled because they are uninformed and whether the consequences of EM are mitigated by altering current disclosure practices. The results have straightforward implications for setting and evaluating prevailing financial disclosure policy. In particular, financial statement users and regulators are increasingly interested in timely information that can be used to assess the quality of reported earnings. For example, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) recently adopted rules intended to narrow the time lag between earnings releases and full financial disclosures. Practitioners also demand that cash flow information be released concurrently with earnings announcements (Randerson, 2004).

The evidence supports the proposition that balance sheet and/or cashflow (hereafter BS/CF) disclosures provided at the time of earnings announcements facilitate timely and informed assessments of potential consequences of earnings management. More specifically, analysis of 10,248 quarterly earnings announcements indicates that security price reactions to earnings disclosures depend on whether BS/CF information, which can be used to estimate the extent that earnings are managed, is released. Average three-day excess security returns in response to all earnings disclosures vary inversely with the extent that earnings appear to be managed upward; but more notably, the price reaction is more substantial and more significant statistically when BS/CF information is released concurrently with earnings press releases. This result persists after considering selection bias that potentially results because BS/CF disclosures are voluntary (Greene, 1981; Heckman, 1979). This evidence, particularly when considered with evidence reported elsewhere (Balsam et al., 2002; DeFond & Park, 2001), suggests that investors attempt to price-protect themselves against EM, and that their ability to do so is enhanced when firms disclose information that can be used to disentangle the consequences of EM.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 considers existing research and develops specific hypotheses. Section 3 explains the methodology, and Section 4 describes data collection procedures. Results are reported in Section 5. Concluding remarks are in Section 6.

2. Motivation

2.1. Existing studies of earnings management and security returns

Early EM studies examine associations between security returns and measures of accruals or discretionary (abnormal) accruals in the context of long-window designs (Rangan, 1998; Sloan, 1996; Subramanyam, 1996; Teoh, Welch, & Wong, 1998a,b; Xie, 2001). Except for Subramanyam (1996), results reported in these studies are typically interpreted as evidence that investors are misled, at least in the short-term, by accrual components of earnings which are considered less substantive than cash components. For example, evidence in Sloan (1996) supports a characterization where naïve investors, who fail to understand the differential persistence in cash flows and accruals, overprice (underprice) stocks where the accrual component is relatively high (low). Evidence in Rangan (1998) and Teoh et al. (1998a,b) suggests that investors are similarly deceived by EM in the context of equity issues. In contrast, Subramanyam (1996, p. 249) reports that discretionary accruals are “priced” in long-window associations. The interpretation of this evidence is that “managerial discretion improves the ability of earnings to reflect economic value.” Footnote 1

Long-window studies, because they do not isolate security price reactions when earnings are disclosed, cannot precisely address whether market participants are misled by EM at the earnings announcement date (EAD) and, if investors are misled, then whether disclosures beyond earnings at the announcement date mitigate the mispricing of securities.

At least two recent short-window studies consider whether and how EM influences earnings interpretations. Using a sample of 14,839 quarterly earnings announcements during 1992–1995, DeFond and Park (2001) report that ERCs (earnings response coefficients) are higher (lower) when unexpected working capital suppresses (exaggerates) the magnitude of earnings surprises. Thus, DeFond and Park (2001) conclude that market participants adjust, at least partially, for suspected earnings management at the time of the earnings announcement. Balsam et al. (2002), noting that the Form 10Q filing with the SEC provides BS/CF information that can be used to estimate the consequences of EM, document a negative association between evidence of earnings management and stock returns over a 17-day window around the 10Q filing date. Footnote 2 Balsam et al. find no price reaction at the press date of earnings announcement, however. Neither of these studies directly considers whether voluntary disclosure of BS/CF information at the quarterly earning announcement explains the extent that investors appear to be misled by earnings management.

2.2. Hypothesis

Price reactions to quarterly earnings announcements potentially inform public policy deliberations regarding the consequences of requiring accounting disclosures beyond earnings. In particular, finding no incremental security price response to discretionary accruals at the earnings disclosure date, regardless of whether balance sheet or cashflow information is provided, suggests that investors are unconcerned about EM or lack the facility required to distinguish EM. On the other hand, a security price reaction to EM at the earnings release date for firms that disclose, but not for firms that do not disclose, suggests both that investors care about EM and that they are able to disentangle the consequences of EM (albeit partially) when requisite information is provided (Balsam et al., 2002). Hence, we investigate how security price reactions differ according to the availability of information used to distinguish EM.

The following hypothesis applies.

Hypothesis

The common stock price response to the size and direction of discretionary accruals is independent of the contemporaneous release of earnings and BS/CF information.

The hypothesis is relevant for assessing prevailing disclosure policies and practices. In particular, existing policies permit, but do not require, firms to disclose BS/CF information which provides a basis for estimating discretionary accruals. Thus, evidence that security prices respond to discretionary accruals more substantially (or only) for firms that provide BS/CF information with earnings disclosures suggests that requiring such information with earnings disclosures would promote more informed interpretations of quarterly earnings. Definitive conclusions about the adequacy of disclosure requirements are not straightforward, however, because the disclosure of BS/CF information is voluntary. We therefore consider selection bias that potentially results from voluntary disclosures of information beyond earnings.

3. Methodology

Consider the following specification, which relates EM and abnormal returns realized at the earnings announcement date (EAD).

where CARi,t is the quarter t cumulative excess return during the event period; UE i,t is unexpected earnings per share (as reported); DACCi,t is the security market’s assessment of quarter t abnormal managed accrual component, where a positive (negative) value indicates an earnings overstatement (understatement); and MVi,t is the market price per share 2 days prior to the EAD.

Earnings forecast error (UE), computed as reported EPS less the most recent security analysts’ EPS forecast, considers the security price consequences of unexpected earnings. The estimate β1 on UE is shown rather conclusively to be positive in the extant literature. The second variable in expression (1), DACC, indicates the impact of EM. If market participants in the aggregate are naively fixed on reported earnings (e.g., Hand, 1990; Rangan, 1998; Teoh et al., 1998a, b), or if they are uninformed about managed earnings components at the time of earnings announcement, then security price reactions to earnings announcements are independent of DACC; that is, β2 = 0. On the other hand, if market participants care about and are informed about EM, then we expect statistically significant estimates β2. In particular, β2 < 0 indicates that earnings components attributable to EM are discounted, whereas β2 > 0 indicates investors assign greater value to earnings components that result from EM.

As part of our testing approach, we adapt expression (1) to distinguish samples composed of “on-target” quarterly earnings announcements—that is, quarterly earnings announcements where earnings meet, but do not exceed or fall short of, the most recent analyst forecast. Applying expression (1) to an on-target sample where UEi,t = 0 for all observations yields

Notice that, for on-target earnings, true unexpected earnings are affected only by the extent of managed component. That is, unexpected earnings are zero under the null hypothesis that earnings are not managed. If earnings are managed, then (true) unexpected earnings differ from zero only to the extent of earnings management.

Distinguishing on-target observations has at least two advantages that potentially increase the ability to detect associations between security returns and DACC. First, management’s incentive to meet earnings expectations is now well documented (e.g., Burgstahler & Dichev, 1997; Degeorge, Patel, & Zeckhauser, 1999), and existing evidence indicates that an on-target sample likely contains relatively more instances of EM than a sample of earnings announcements where earnings differ from expectations (Degeorge et al., 1999).

Second, on-target observations facilitate parsimonious specifications of associations between security returns and EM, which are unlikely to be obscured by earnings surprises that dominate security price reactions in most cases. In particular, the underlying (true) earnings surprise for on-target disclosures differs only to the extent of EM. That is, for a sample composed of on-target disclosures exclusively, UE=0 for all observations such that the underlying earnings surprise is nil by construction (if earnings are not managed) or differs only to the extent of earnings management (if earnings are managed). Moreover, unexpected earnings need not be considered in the regression specification. This feature of the sample avoids issues of, as examples, nonlinearity in return-earnings relations, the choice of the deflator for unexpected earnings, and unknown biases in parameter estimates that potentially result when more than one independent variable (unexpected earnings and discretionary accruals) are measured with error (Levi, 1973).

Next we consider the availability of BS/CF information at the earnings announcement date. In contrast with assumptions made in prior studies (e.g., Wilson, 1986, 1987), evidence in Chen, DeFond, and Park (2002)—hereafter CDP—indicates that a significant number of firms disclose BS/CF details with quarterly earnings. We use hand-collected disclosures identified by CDP to investigate how the security price reaction to EM depends on the availability of BS/CF information that can be used by outsiders to estimate potential EM. Footnote 3

BS/CF disclosures are voluntary, and thus, we need to control for the possibility that firms that disclose BS/CF differ systematically from non-disclosing firms. In particular, CDP report that firms that (1) are in high technology industries; (2) report losses; (3) have larger forecast errors; (4) execute mergers or acquisitions; (5) are younger; and (6) have volatile stock returns, are more likely to disclose BS/CF information. We use Heckman’s (1979) two-step approach to address potential selection bias that could result from ignoring the decision to disclose BS/CF information.

To this end, consider the following relations for observations where BS/CF information is provided and for observations where it is not.

The objective is to evaluate whether γ1 = 0(ϕ1 = 0) in the absence of self-selection. If BS/CF is disclosed randomly, then expressions (3) and (4) can be estimated using OLS. We know that BS/CF is not provided randomly, however, which implies that E(ɛi,t/BS/CF is provided) ≠0 and E(νi,t/BS/CF is not provided) ≠0. Therefore, OLS estimates for these equations can be biased.

To address the problem, we express the decision to disclose BS/CF as follows.

where I = 1 when BS/CF is disclosed and I=0, otherwise; β are coefficients on a matrix Z of variables that influence decisions to disclose BS/CF; and \(\varpi\) is an error term. We use variables identified in CDP to specify Z.

Under the Heckman approach, expression (5) is estimated as a probit specification. Parameter estimates and residuals are used to construct the inverse Mills ratio, which is an additional explanatory variable in the primary specification. In particular, expression (1) is restated as

where α i are parameter estimates, and Lambda (the inverse Mills ratio) is computed as ϕ(Z′ bΦ Z′ b) here b is the vector of estimates for β, and ϕ(·) and Φ(·) respectively the normal probability density function (PDF) and the cumulative normal probability density function (CDF) obtained from the probit estimation of expression (5). Simply stated, Lambda controls for factors that govern management’s decision to disclose summary BS/CF information along with earnings.

4. Data and sample

Table 1 summarizes the sample selection process. The CDP sample includes 23,086 firm-quarter observations. We use earnings forecast data from the I/B/E/S data file. Unexpected earnings (UE) is computed as UE = actual EPS—forecast EPS, where forecast EPS is the most recent quarterly earnings forecast before the earnings announcement date (EAD). Footnote 4 Using the most recent individual analyst forecast from the I/B/E/S detail file, rather than the I/B/E/S consensus forecast, avoids measurement error in the I/B/E/S data that potentially results from rounding split-adjusted observations (Baber & Kang, 2002; Payne & Thomas, 2003). Footnote 5 To ensure consistency in computing UE, actual EPS also are from I/B/E/S. Footnote 6 Table 1 shows that we eliminate 6602 observations that lack forecasts on the I/B/E/S file.

We use conventional procedures to compute CAR. In particular, we estimate the market model from 170 to 21 days prior to the earnings announcement date (EAD) and use the parameter estimates to compute risk-adjusted abnormal returns. Comparing earnings announcement dates (EAD) on the I/B/E/S and COMPUSTAT files indicates differences greater than one trading day for 2.8% of the sample (667 of 23,086 observations). These observations are omitted to ensure that the EAD are accurately identified (see Table 1). Because EADs are potentially mis-aligned by 1 day for the remaining observations, we cumulate abnormal returns (CAR) for three event windows: 1 day (the EAD, day 0), 2 days (days −1 and 0), and 3-days (days −1, 0, and +1). Reported results are for 3-day CAR, although results are comparable for the 1- and 2-day measures. Notice from Table 1 that we eliminate 141 observations that lack security returns on CRSP that are required to compute CAR.

Consistent with procedures used to compile publicly-available EPS forecast databases, we compute accruals excluding “non-operating” accruals attributable primarily to non-recurring items such as mergers, restructurings, and gains/losses from asset sales. In particular, following Bahnson, Miller, and Budge (1996) and Hribar and Collins (2002), we use information from cashflows statements to compute total accruals, designated TACC. Footnote 7 Specifically, TACC = −(decrease in accounts receivable [103]+decrease in inventory [104]+increase in account payables and accrued liabilities [105]+ increase in accrued income taxes [106]+net change in other assets and liabilities [107]+depreciation [77]+deferred taxes [79]) [COMPUSTAT quarterly item numbers in brackets].

We estimate discretionary accruals using the Jones model (1991) modified to accommodate quarterly data. Jones model regressions are estimated on a firm-by-firm basis with both accruals (TACC) and changes in revenues (ΔREV) specified as changes over successive quarters. Parameter estimates on the event dummy (set equal to one for the event quarter; zero, otherwise) indicate discretionary accruals (DACC) scaled by beginning total assets. Footnote 8 We are concerned that seasonality in the Jones model DACC estimates induces spurious relations between DACC and security price reactions to quarterly earnings. To address this concern, we regress discretionary accrual estimates on four quarterly dummy variables using a pooled, time-series cross-sectional approach. Residuals from this specification are a seasonally-adjusted indicator of discretionary accruals. We eliminate 5016 observations that lack the data required to estimate the Jones model (see Table 1).

Finally, notice in Table 1 that we omit 196 observations with UE and DACC in the top and bottom one percentile of the respective distributions. These procedures leave 10,248 firm quarter observations, which is 44.4% of the CDP sample.

Descriptive statistics for this sample are displayed as Table 2. Columns in Panel A indicate distributions according to whether summary balance sheets and/or cashflow statements are disclosed along with earnings at the EAD, and the rows indicate whether the earnings are on-target—that is, whether reported earnings equal the most recent analyst forecast before the EAD. Notice that supplemental BS/CF information is available for 40.7% of the earnings announcements, and reported earnings are on-target for 15.1% of the announcements. For 89.0% of earnings announcements where BS/CF information is disclosed, the firm also discloses BS/CF information in the preceding quarter, which suggests that firms benefit from a stable disclosure policy. Notice also from the table that these classifications of the sample are independent statistically (P = 0.52), that is, the incidence of exactly meeting the EPS expectation is unrelated to the disclosure of BS/CF information.

Panel B of Table shows distributions for unexpected earnings (UE), 3-day returns at the EAD (CAR), and the Jones-model estimate of discretionary accrual (DACC) scaled by the market value. The first row suggests almost no difference between forecasted and reported earnings in the aggregate. In particular, the median forecast error is zero, although owing to the large sample size, mean forecast error (−0.0009) is statistically significant.

Distributions for CAR, the 3-day return centered on the EAD are displayed next. Notice that we use Z-statistics to evaluate the statistical significance of the mean portfolio returns (Brown & Warner, 1985). Footnote 9 Distributions for DACC, the discretionary accrual estimate of earning management, are displayed at the bottom of the table.

Comparing distributions of CAR and DACC for the on-target sub-sample indicate at least two points worth noting. First, the mean discretionary accrual component for on-target observations is positive, which implies that managers, on average, manipulate accruals to achieve the earnings benchmarks established by analysts. These results, which are consistent the characterization implied by Burgstahler and Dichev (1997) and Degeorge et al. (1999), suggest that managers are particularly concerned about meeting earnings benchmarks. Second, the mean security price reaction to all on-target announcements is negative, suggesting an unfavorable average market reaction when reported EPS just meets the forecast. One explanation for this result is that investors interpret on-target reports unfavorably because they (rationally) assign a relatively high probability that managers achieve earnings targets through earnings management.

5. Multivariate results

5.1. Probit specifications

Table 3 presents the probit specification, expression (5), which is the first-stage of the Heckman procedure. Recall that the dependent variable in the specification is set to one when supplementary balance sheet or cashflow statements are provided; zero, otherwise. Explanatory variables, and the corresponding expected directions of the effects, are identical to those considered in quarter-by-quarter logit specifications reported in CDP (Table 4 on p. 243), except that we eliminate a dummy variable to indicate whether the forecast error exceeds one percent of the forecast for UE = 0 observations. Results displayed in the table are similar to those in CDP in all respects.

5.2. Primary results

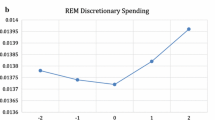

Table 4 shows second-stage regression specifications of CAR, 3-day cumulative returns realized at the EAD, delineated by the availability of BS/CF information. Footnote 10 The top panel contains estimates for stock price reaction when BS/CF information is not made available. The bottom panel shows results when BS/CF information is available. The first (second) column is for observations where earnings differ from (equal) the most recent forecast, and the third column is for all observations. Consistent with results reported in many prior studies, estimates on unexpected earnings (UE/MV) in the first column are positive and statistically significant, regardless whether BS/CF information is available.

Comparing estimates on DACC in Panel A with the corresponding estimates in Panel B indicates the primary contribution of the study. In particular, these comparisons indicate statistically significant estimates on DACC when supplementary information is disclosed along with earnings (Panel B), but not when earnings are disclosed without supplementary information (Panel A). The implication is that investors use supplementary disclosures to identify earnings components that potentially result from attempts to manage earnings.

Another significant point is that the mean magnitude of parameter estimates on DACC when quarterly earnings are on-target (the second column of Panel B) are more than twice that of the corresponding estimates when earnings do not exactly equal the analyst forecast (the first column of Panel B). This result apparently justifies distinguishing UE=0 observations in the design of the analysis. That is, the result supports the argument that on-target observations offer a more powerful test because incentives to meet analysts’ forecasts are particularly compelling, and/or because the more parsimonious specification that results from restricting the analysis to on-target observations reduces the possibility that parameter estimates on DACC are obscured by measurement error in other explanatory variables.

5.3. Results for other procedures

If the measure of EM DACC is, for whatever reason, correlated with unspecified factors that also influence security price responses to earnings announcements, then results in Table 4 can be spurious. For example, evidence in McNichols (2000) suggests that measurement error in managed accruals is related to growth and firm size. Thus, we execute procedures designed to evaluate the robustness of the associations. We begin by expanding expression (6) to include additional explanatory variables that consider the possibility that associations for DACC are attributable to firm characteristics. First, we consider non-discretionary accrual (NACC), computed as total accruals (TACC) less DACC, for the possibility that the negative association between returns and accruals is due to non-discretionary, rather than discretionary, accrual components. Next, revenues can have information content beyond earnings, and thus, we are concerned about whether our results indicate security price reactions to revenue, rather than to earnings. To investigate whether this explanation applies, we consider (1) sales growth; the growth rate of revenue over the 2 years; and (2) unexpected sales revenue information announced in quarter t. Footnote 11 Other potentially omitted variables include future growth expectations, firm risk, and firm size. Thus, we consider systematic risk estimated from the standard market model, but do not consider variables that are already considered in the first-stage logit regression, such as market-to-book ratio, firm size, or whether the firm reports a loss.

Table 5 displays results for the second stage, delineating the sample by whether or not BS/CF information is disclosed. Notice that the estimate on NACC is statistically significant in none of the specifications, suggesting that interpretations of earnings are conditioned specifically on discretionary, not on non-discretionary or total accruals. Footnote 12 In general, including additional variables—namely sales growth, unexpected sales revenue, or systematic risk—does not substantially impact estimates for DACC or UE.

We also consider potential measurement error in DACC by investigating whether results are robust to alternative approaches considered in the literature to estimate EM. In particular, we estimate discretionary accruals DACC using the Jones model estimates based on total accruals computed from the balance sheet, and procedures advanced in Kang and Sivaramakrishnan (1995) and in Kothari, Leone, and Wasley (2005). Results (not reported) for these procedures do not alter inferences based on the evidence in Table 4. Footnote 13

Another issue is the extent that the most recent analyst forecast deviates from market expectations at the EAD. If the most recent forecast does not indicate market expectations, and if the resulting error in UE is systematic, then estimates on DACC can be biased. Following Brown, Griffin, Hagerman, and Zmijewski (1987), we address this concern by including cumulative abnormal return during the 20 trading days (about one calendar month) prior to the earnings announcement (days −21 to −2). Footnote 14 The objective is to control changes in earnings expectations attributable to events or information disclosures after the most recent forecast. Consistent with expectations, we find negative estimates for the cumulative returns, which indicate the reversal of returns realized during the period leading up to the EAD as the market anticipates earnings that differ from the prevailing forecast. Including the variable does not substantially affect parameter estimates on DACC, however.

Finally, results are comparable when we use size-adjusted returns and market-adjusted returns (firm returns less the return on the value-weighted CRSP index) to compute CAR.

6. Concluding remarks

We find that 3-day excess returns around quarterly earnings disclosures vary inversely with measures that indicate potential earnings management. Such results, when with evidence reported in elsewhere (Balsam et al., 2002; DeFond & Park, 2001), suggest that market participants are aware of incentives to manage reported earnings, and accordingly, they adjust for earnings management when they are provided the information required to do so.

More significantly, we find that negative associations between security price reactions and EM indicators are stronger when supplementary BS/CF information, which facilitates distinguishing discretionary accruals from other earnings components, is disclosed along with earnings than when such information is not disclosed. This result, which is consistent with Balsam et al. (2002) regarding price reactions to the 10Q release, is robust to procedures designed to consider potential self-selection bias that results because disclosure of supplementary information is voluntary. The implication is that investors distinguish EM when the requisite information is available—that is, when BS/CF information and earnings are disclosed concurrently. Footnote 15

This point raises the issue of why some, but not all, firms disclose information that helps investors disentangle EM. Resolving this issue is beyond the scope of the study, but notice that managers can have other motives to disclose information beyond what is required (Chen et al., 2002; Verrecchia, 1983). If so, then firms that—for whatever reason—establish a policy to disclose BS/CF information along with quarterly earnings may be reluctant to alter the policy in specific quarters when earnings are managed. Moreover, BS/CF disclosure does not permit investors to unravel EM perfectly, so managers can benefit from EM even when a supplementary disclosure policy is in place.

Finding that security prices respond to evidence of earnings management primarily when BS/CF information is disclosed is relevant for evaluating prevailing disclosure rules which permit, but do not require, firms to disclose earnings and BS/CF details concurrently. In particular, the evidence demonstrates that balance sheet or cashflow disclosures at the time of earnings announcements encourage informed and timely evaluations of quarterly earnings. The implication is that requiring that balance sheet and/or cashflow information accompany earnings disclosures would facilitate earnings interpretations. Mandating such disclosures needs to be balanced against the costs of additional disclosures, including potential delays in earnings announcements, however.

Notes

Consistent with the notion that sophisticated investors respond to earnings management before the 10-Q filing, the negative association around the 10-Q filing is found only for a subset of firms whose owners are presumed less sophisticated (as indicated by low institutional ownership).

“BS/CF disclosures” range from summary balance sheets to full-blown balance sheets and cashflow statements. The details on the extent of disclosures are not identified for individual firms.

We restrict our analysis to forecasts made within the 120 days prior to the EAD.

Brown (2001) reports that the most recent individual forecast is as accurate as the consensus, and unexpected earnings computed using the most recent forecast is more highly correlated with security returns.

Actual EPS from the COMPUSTAT file are not uniformly comparable with forecast EPS in First Call. As examples, analysts can ignore unusual items that are considered earnings components in COMPUSTAT (Philbrick & Ricks, 1991), and because adjustments are anchored on different dates, split adjustment factors in I/B/E/S can differ from those in COMPUSTAT.

COMPUSTAT reports quarterly cashflow statements on cumulative 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-months bases relative to the first quarter. Thus, except for the first quarter, components of TACC are computed as the difference relative to the prior quarter.

Estimates for event dummy variables are identical to the “prediction error” from a regression on a sample that excludes the event time observation. Following convention, we require at least ten quarterly observations for each firm to execute the Jones model estimation.

Let R t be the average return to the portfolio of firms on day t. The Z statistic for day t is R t /σ, where σ is the sample standard deviation of the mean portfolio returns during the estimation period (t = −171 to −20).

Standard errors of the second stage estimates are corrected using the procedure suggested in Greene (1981).

This is defined as quarter t revenue less expected revenue, computed as revenue reported in the same quarter in the prior year (quarter t-4) adjusted for revenue growth realized in the prior quarter(quarter t-5 divided by quarter t-1 revenue).

Notice that, if NACC is replaced by total accruals TACC, then the parameter estimate on TACC is identical to that on NACC by construction. Thus, the result for NACC implies that the primary results are robust to including either NACC or TACC in the specification.

Neither approach yields results stronger than what is reported in Table 4, however.

Results are comparable when returns are cumulated 5 or 30 calendar days prior to EAD.

Such evidence would not necessarily imply, however, that the timing and the extent of prevailing disclosures are optimal or even adequate.

References

Baber, W., & Kang, S. H. (2002). The impact of split adjusting and rounding on analysts’ forecast error calculations. Accounting Horizons, 16(4), 277–289.

Bahnson, P., Miller, P., & Budge, B. (1996). Nonarticulation in cash flow statements and implications for education, research, and practice. Accounting Horizons, 10(4), 1–15.

Balsam, S., Bartov, E., & Marquardt, C. (2002). Accruals management, investor sophistication, and equity valuation: Evidence from 10-Q filings. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(4), 987–1011.

Brown, L. (2001). A temporal analysis of earnings surprises: Profits and losses. Journal of Accounting Research, 39(2), 221–241.

Brown, S., & Warner, J. (1985). Using daily returns: The case of event studies. Journal of Financial Economics, 14(1), 3–31.

Brown, L., Griffin, P., Hagerman, R., & Zmijewski, M. (1987). An evaluation of alternative proxies for the market’s assessment of unexpected earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 9(2), 159–194.

Burgstahler, D., & Dichev, I. (1997). Earnings management to avoid earnings decreases and losses. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 24(1), 9–126.

Chen, S., DeFond, M., & Park, C. (2002). Voluntary disclosures of balance sheet information in quarterly earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33(2), 205–227.

DeFond, M., & Park, C. (2001). The reversal of abnormal accruals and the market valuation of earnings surprises. The Accounting Review, 76(3), 375–404.

Degeorge, F., Patel, J., & Zeckhauser, R. (1999). Earnings management to exceed thresholds. Journal of Business, (January), 1–34.

Greene, W. (1981). Sample selection bias as a specification error: A comment. Econometrica, 49(3), 795–798.

Hand, J. (1990). A test of extended functional fixation hypothesis. The Accounting Review, 65(4), 739–763.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Hribar, P., & Collins, D. (2002). Errors in estimating accruals: Implications for empirical research. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(1), 105–134.

Jones, J. (1991). The effect of foreign trade regulation on accounting choices, and production and investment decisions. Journal of Accounting Research, 29(2), 193–228.

Kang, S. H., & Sivaramakrishnan, K. (1995). Issues in testing earnings management and an instrumental variable approach. Journal of Accounting Research, 33(2), 353–368.

Kothari, S. P., Leone, A., & Wasley, C. (2005). Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(1), 163–197.

Levi, M. (1973). Errors in the variables bias in the presence of correctly measured variables. Econometrica, 41(5), 985–986.

McNichols, M. (2000). Research design issues in earnings management studies. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 19(4–5), 313–345.

Payne, J., & Thomas, W. (2003) The implications of using stock-split adjusted I/B/E/S data in empirical research. The Accounting Review, 78(4), 1049–1067.

Philbrick, D., & Ricks, W. (1991). Using value line and I/B/E/S analyst forecasts in accounting research. Journal of Accounting Research, 29(2), 101–122.

Randerson, E. (2004). In an era of full disclosure, what about cash? Financial Executive, 20(6), 48–50.

Rangan, S. (1998). Earnings management and performance of seasoned equity offerings. Journal of Financial Economics, 50(1), 101–122.

Sloan, R. (1996). Do stock prices fully reflect information in accruals and cash flows about future earnings? The Accounting Review, 71(3), 289–316.

Subramanyam, K. R. (1996). The pricing of discretionary accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 22(1–3), 249–281.

Teoh, S. H., Welch, I., & Wong, T. J. (1998a). Earnings management and the underperformance of seasoned equity offerings. Journal of Financial Economics, 50(1), 63–99.

Teoh, S. H., Welch, I., & Wong, T. J. (1998b). Earnings management and the long-run market performance of initial public offerings. Journal of Finance, 53(6), 1935–1974.

Verrecchia, R. (1983). Discretionary disclosure. Journal of Accounting & Economics, 5, 179–195.

Wilson, G. P. (1986). The relative information content of the accrual and cash flows: Combined evidence at the earnings announcement and annual report release dates. Journal of Accounting Research, 24(Suppl.), 165–200.

Wilson, G. P. (1987). The incremental information content of the accrual and funds components of earnings after controlling for earnings. The Accounting Review, 62(2), 293–322.

Xie, H. (2001). The mispricing of abnormal accruals. The Accounting Review, 76(3), 357–373.

Acknowledgements

We thank Chris Jones, Krishna Kumar, Konduru Sivaramakrishnan, Karen Taranto, Sam Tiras, Kumar Visvanathan, Scott Whisenant, Michael Willenborg, Carol Yu, and workshop participants at the University at Buffalo, the University of Connecticut, the University of Houston, the University of Maryland, and Virginia Tech for comments in prior versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baber, W.R., Chen, S. & Kang, SH. Stock Price Reaction to Evidence of Earnings Management: Implications for Supplementary Financial Disclosure. Rev Acc Stud 11, 5–19 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-006-6393-0

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-006-6393-0