Abstract

Using the latest mental health cycle of the Canadian Community Health Survey (N = 20,868), this paper examines how the importance of religion or spirituality in one’s life associates with mental health. Based on this question, the population is divided into three groups of high religiosity, average religiosity, and secularized. Secularized individuals are shown to have large deficits in all the psychological markers suggested to mediate the relationship between religiosity and mental health, compared to the two other groups. In spite of these deficits, the secularized and the highly religious are found almost equally more likely to rate their mental health as excellent, than the individuals with average religiosity. Interestingly, these two groups are also more likely to rate their mental health as poor. Considering the ability to deal with day-to-day demands and unexpected problems in life as the dependent variable yields comparable results. Various explanations are explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The positive association of religious or spiritual involvement with mental health is extensively documented since the late 1980s (Ellison and Levin 1998; Hackney and Sanders 2003; Koenig et al. 2012). Until recently, in North America where most studies have been conducted, secular groups constituted a negligible minority. Consequently, the positive association of religiosity with mental health revealed in these studies indicates how the highly religious differs from the average, and not the secularized minority. In fact, most previous studies assess how the “degree” of religious involvement associates with mental health. This conception is only valid if one can assume that a degree of religious involvement is universal, and the impact of involvement is uniform in the reference population. The recent trends of secularization, however, strongly undermine the validity of such assumptions. Accordingly, there has been a surge of interest in the scientific study of various types of secularized individuals (Hout and Fischer 2002; Bainbridge 2005; Smith 2011; LeDrew 2013; Cimino and Smith 2014) and the association of secularity with well-being outcomes (Hwang et al. 2011; Weber et al. 2012; Hayward et al. 2016).

Recent data indicate that above 20% of Canadians state that religion or spirituality is “not important at all” in their daily life. About half of this group has no tie with either religion or spirituality, even in a private manner. More strikingly, 42% of Canadians, religiously affiliated or not, state that they “never” attend religious services (Wilkins-Laflamme 2015). The implications of this new landscape, characterized by an increased secularization (Thiessen and Dawson 2008; Eagle 2011; Hay 2014), for mental health outcomes of Canadians have not been explicitly addressed. With the growth of secular groups, this question can be framed in terms of a comparison in the mental health outcomes of different segments of the population, differentiated based on their attitude towards religion or spirituality. This approach is taken in the present study, using a large Canadian data set. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The related literature is reviewed first. “Data and Methodology” section describes the data and the methodology. The results are reported in “Results” section. “Discussion” section discusses several implications of the results. The concluding remarks follow.

Literature Review

A host of studies reports the positive association of religiosity with mental health outcomes (Ellison and Levin 1998; Hackney and Sanders 2003; Koenig et al. 2012). Religion is a multidimensional construct, with public and private aspects (Sherkat and Ellison 1999). Religious service attendance is commonly distinguished from private dimensions of religiosity, namely the strength of beliefs and the frequency of prayer (Schnittker 2001; Maselko et al. 2009). Religious attendance promotes the accumulation of social capital through community membership (Wuthnow 2002; Putnam and Campbell 2010) and helps with the creation of networks of mutual aid (Idler 1987; Strawbridge et al. 1997; Krause 2011). However, the possibility of negative interaction with coreligionists and its deleterious impact on well-being has also been noted (Nielsen 1998; Krause et al. 2000). Non-religious individuals seem likely to suffer in terms of the social support stemming from religious attendance.

It has been suggested that the benefit a churchgoer draws from religious attendance depends not only on her own involvement, but also on the presence of other coreligionists, and their engagement with the services (Iannaccone 1992, 1994). A society-wide decline in religious attendance is, therefore, likely to negatively impact its benefit to the remaining churchgoers. The protracted fall in the Canadian religious attendance is documented in the recent scholarship (Thiessen and Dawson 2008; Eagle 2011; Hay 2014). This lack of vibrancy is likely to reduce mental health benefits of churchgoing. On the other hand, the bourgeoning secular movements and communities integrate elements such as a shared identity and belonging to a social group, which may partially match the mental health benefits of religious attendance (Cimino and Smith 2011, 2014; Smith 2013). These observations suggest that, in Canada, the mental health advantage resulting from religious attendance is currently lower than what could be expected based on previous US studies.

Private dimensions of religion and spirituality are suggested to provide meaning, optimism, and comfort, all of which are predictors of a better mental health (Koenig 1995; Levin and Chatters 1998; Krause and Hayward 2012a). A few studies report a positive association with negative feelings (Allport and Ross 1967; Johnson et al. 2010). Ellison and Lee (2010) report evidence on the negative mental health impact of spiritual struggle, relevant only to the religious believer. Silton et al. (2014), using the American Baylor Religion Survey (N = 1426), report that belief in a punitive (benevolent) God is positively (negatively) associated with psychiatric symptoms, controlling for demographic characteristics.

Uncertainty and ambiguity create an undesirable mental state of aversion (Kahneman and Tversky 1982). The existential certainty associated with strong beliefs is suggested to yield salutary effects, by reducing anxiety and cognitive dissonance (Salsman et al. 2005; Stark and Maier 2008). Some studies suggest that this relationship is symmetrical, and both strong religiosity and strict secularity are associated with better mental health (Shaver et al. 1980; Speed and Fowler 2016). A degree of existential uncertainty is inherent to agnosticism which can reduce mental well-being (Hogg et al. 2010; Vail et al. 2010). The same is true for the religiously affiliated whose beliefs are not solid, or experience religious doubt (Krause and Wulff 2004; Galek et al. 2007; Ellison et al. 2009; Krause and Hayward 2012b). A careful review of the extant literature shows that most studies document a positive effect for religious or spiritual belief as means of coping (Pargament and Park 1997; Hess et al. 2014), while the evidence on its protective impact is thinner (Hwang et al. 2011; Weber et al. 2012). No study thus far has focused on the Canadian context. The cumulative weight of extant evidence, however, suggests that one can expect to see a positive association between strong religious or spiritual beliefs and mental health in Canada, generally considered to be more secular than the USA (Lyon and Van Die 2000).

Increasingly, scholars explicitly distinguish between the religiously affiliated and various categories of secular groups (Smith-Stoner 2007; Horning et al. 2011; Weber et al. 2012). Among the secular groups, atheists receive the most vigorous scholarly attention (Whitley 2010; Hwang 2013). Hayward et al. (2016), using the American Landmark Spirituality and Health Survey (N = 3010), report that atheists and agnostics have worse health outcomes, than both the affiliated and religious nones. Speed and Fowler (2016), using the American General Social Survey (N = 3210), report that non-belief in God is an insignificant predictor of health. Atheism has also been linked to poorer health outcomes (Baker and Cruickshank 2009). Conversely, some studies report that atheism predicts better health outcomes (Buggle et al. 2001; Wilkinson and Coleman 2010). Weber et al. (2012) review the literature on mental health outcomes of secular groups, reporting negative perception by others as a major source of distress among them. The prejudice against atheists is consistently documented for the USA (Edgell et al. 2006; Gervais et al. 2011; Gervais and Norenzayan 2013; Doane and Elliott 2015). However, it has been reported that, with the increasing prevalence of atheism (Gervais 2011) and in the contexts of secular rule of law (Norenzayan and Gervais 2015), the anti-atheist prejudice decreases.

With the growth of secularization across the world, scholarship suggests that the relationship between religiosity and well-being outcomes is contextual and dependent on the degree to which religiosity is embedded in the society (Gill et al. 1998; Suh 2002; Diener et al. 2011). For instance, in Scandinavian countries where the life satisfaction levels are among the highest in the world, the majority of the population is non-religious (Koenig and Larson 2001). In difficult circumstances, religion offers spiritual support, ultimate explanation, and a purpose in life (Pargament 2002). In prosperous nations, people need fewer additional coping mechanisms beyond their personal resources; hence, religion has a smaller association with life satisfaction (Diener et al. 2011). Across nations, religious individuals are found to be either very satisfied or very dissatisfied with life (Okulicz-Kozaryn 2010). The systematic review of Weber et al. (2012) also reports evidence congruent with such a bimodal relationship.

Methodologically, without incorporating the required flexibility in the modelling process, nonlinear patterns of association or differences in the underlying distributions remain undetected. A few studies have examined the existence of nonlinear patterns (Ross 1990; Eliassen et al. 2005) or distributional differences (Buggle et al. 2001; Diener and Clifton 2002). Riley et al. (2005) report that both the highly religious and the atheists score the lowest on depressive symptoms, which suggest a u-shaped relationship between the “degree” of religiosity and mental health. Many of these studies rely on a bivariate analysis, without accounting for confounding factors, such as socioeconomic status and gender (Ross 1990; Diener and Clifton 2002; Riley et al. 2005). Galen and Kloet (2011), using a sample of mostly American adults (N = 333), report a u-shaped relationship between religiosity and mental health, controlling for demographic and socioeconomic covariates.

In the mental health and religion literature, Canadian data have been scantly employed (Baetz et al. 2004). A few studies have reported the positive association of religiosity with life satisfaction, using Canadian data (Hunsberger 1985; Gee and Veevers 1990; Frankel and Hewitt 1994; Dilmaghani 2016). The present paper uses a recent nationally representative data set to examine how the importance of religion or spirituality in one’s life associates with mental health indicators, in Canada. The main goal of this investigation is to elicit information on the current relationship between religious or spiritual belief and mental health, in the general population. The size and the quality of the data set insure this. The modelling process allows for detecting nonlinear relationships between the variables, if present.

Data and Methodology

This study uses the latest cycle of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) focused on mental health, conducted in 2012 (Statistics Canada 2013). This nationally representative data set contains 25,113 observations. Immigrants are excluded from the analysis, to achieve a more culturally homogeneous sample.Footnote 1 This restriction brings the number of observations to 20,868. In the regressions, observations containing missing data are handled with listwise deletion. The data set includes the standard question on the importance of religion or spirituality in one’s life. The respondents are asked “In general, how important are religious or spiritual beliefs in your daily life?” with a 4-item response scale, starting from “very important” to “not important at all.” Using this question, the population is divided into three segments. The “highly religious” pertains to the group of respondents who state that their religious or spiritual beliefs are very important to them. They make up 32% of the sample. The “secularized” group, with 22% share, includes those who state that their religious or spiritual beliefs are not at all important in their daily life. The remaining 46% constitutes the third group, and the omitted category in the regressions. The association of belonging to these segments of the population with an array of mental well-being outcomes is examined, using multivariate regression analysis.

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics on the three mental well-being outcomes examined in this paper, which are (1) self-rated mental health; (2) self-rated ability to deal with day-to-day demands of life; (3) self-rated ability to handle unexpected and difficult problems in life. As the table shows, the mean scores are remarkably close across the three groups, for all the three outcomes. However, when the extremities of the distributions are considered, the differences emerge. For all the outcomes, the two segments of highly religious and secularized are more likely than the individuals with average religiosity to select a rating of excellent or poor.

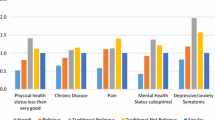

As the CCHS does not include additional religion-related information, such as the frequency of religious attendance or private prayer, finer distinctions across the population are impossible.Footnote 2 But, the robustness of this classification in reliably separating the segments of the population based on their worldviews is examined, using a set of psychological markers. Spirituality or religiousness has been defined in many studies by characteristics reflecting purpose and meaning in life, connectedness with others, perception of social support, and serenity (Ellison and Levin 1998; Koenig 2008; Hwang et al. 2011). Five CCHS questions are used to examine how the highly religious compares with the secularized, with respect to these characteristics. These questions, surveying the respondents on their frequency of experiencing a set of emotions, are listed and defined in Table 2. The response categories corresponding to these questions have a 6-item scale, starting from “daily” to “never”. The responses are quantified to correspond to monthly frequencies, varying between 30 for daily and 0 for never.

As evident from Table 2, all these markers appear to be higher for the highly religious, compared to the two other groups. Prior to using this classification in assessing mental health outcomes, multivariate regression analysis is used to insure that the differences among these segments of the Canadian population are impervious to the inclusion of demographic and socioeconomic controls.

Next, this paper examines how belonging to these segments of the population associates with (1) self-rated mental health; (2) self-rated ability to deal with day-to-day demands of life; (3) self-rated ability to handle unexpected and difficult problems in life. The models are conceived to reveal nonlinear patterns, if present. A wide range of controls, such as gender, age, household size, level of education, marital status, income, employment status, ethnic background, and location of residence, is included in the regressions. All the estimations are made using the survey weights.

Results

Table 3 reports a set of five OLS estimations. The dependent variables are natural logarithms of the monthly frequencies of experiencing the outcomes listed in Table 2. As such, the estimated coefficients reveal the percentage changes in the dependent variables. Since all the coefficients are positive (negative) for the highly religious (secularized), the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients indicates the difference between the two groups. These psychological markers overlap with how having a religious or spiritual outlook in life is defined in the literature (Hill et al. 2000; Hill and Pargament 2008; Hwang et al. 2011). Concepts closely linked to these markers are suggested to mediate the relationship between religiosity and mental health (Ellison and Levin 1998). Another strand of literature refers to these characteristics as indicators of social capital (Lochner et al. 1999; McKenzie et al. 2002; Almedom 2005). This set of regressions, in addition to its own scholarly interest, gauges the meaningfulness of the classification employed in this paper.

As shown in Column (1), the highly religious individuals assert that they contribute something important to the society 47% more frequently than the secularized. As reported in Column (2), the highly religious feels that they belong to a community 60% more often than the secularized individuals. Column (3) shows that the secularized asserts that the society improves for them, 46% less frequently than the highly religious. Column (4) produces evidence that the secularized 34% less often regards the challenges in life as means of self-improvement. Finally, as reported in Column (5), the secularized asserts a sense of direction or meaning in their life 30% less frequently than the highly religious. The regressions control for a wide range of covariates listed as note to the table. As the results demonstrate, these three segments of the population substantially differ from each other in the way they experience the world. A number of other comparable metrics, such as the feeling that people are generally good and trustworthy, have been considered, yielding similar results. One can, therefore, be confident that in the following analyses, two segments of the population with distinct worldviews are compared.

Table 4 reports a set of four estimations, assessing the association of religiosity with self-rated mental health. The summary statistics reported in Table 1 suggest that both the highly religious and the secularized are more likely than the average to be found at the two ends of the mental health scale, excellent or poor. To verify whether these patterns remain statistically significant when one accounts for demographic and socioeconomic covariates, the mental health outcomes are dichotomized in the first three regressions.

In Column (1), the dependent variable is a dummy that takes the value of one for respondents who self-report of excellent mental health. As the table shows, both groups of the highly religious and the secularized are statistically significantly more likely than the average to self-report of excellent mental health, and the coefficients are fairly close. The dependent variable in the second column is a dummy that takes the value of one for respondents who rate their mental health as excellent or very good. In this regression, the group-identifier coefficients are found statistically insignificant. In Column (3), the dependent variable is a dummy taking the value of one for respondents of poor mental health. Interestingly, both the highly religious and the secularized are more likely than the individuals with average religiosity to experience the outcome.

This set of regressions strongly supports the nonlinearity of the relationship between religiosity and mental health. The relationship between religiosity and both the likelihood of excellent and poor mental health is found to be u-shaped. The individuals whose religiosity is higher or lower than the average are more likely to be at the two ends of the mental health spectrum. In general, in any data set with a similar pattern, accounting linearly for the degree of religiosity and pooling the highly religious and the secularized would either result in a statistically significant and positive relationship, or a statistically insignificant relationship, depending on the relative size of the secularized group. The ordered logit estimation reported in Column (4), yielding statistically insignificant coefficients, illustrates this point. The controls, mostly suppressed in the table to save space, had the expected signs and magnitudes. Females are found to self-report of worse mental health (Rosenfield and Mouzon 2013). Self-employed individuals tend to report superior mental health outcomes, compared to both employees and the unemployed (Bradley and Roberts 2004; Millán et al. 2013). Finally, household income and its adequacy are found to be important positive predictors of mental health (Muntaner et al. 2013).

Table 5 extends the analysis to the self-rated ability to handle day-to-day demands and unexpected problems in life. The results, overall, indicate a nonlinear pattern. As reported in Column (1), both the highly religious and the secularized individuals are more likely than the average to rate their ability to handle life’s day-to-day demands as excellent. As Column (2) reports, there is no statistically significant relationship between religiosity and self-rated poor ability. Regarding the ability to handle unexpected and difficult problems, the secularized individuals are found 5% more likely to rate their ability as excellent, compared to both the highly religious and the average. Conversely, as Column (4) shows the highly religious individuals are found 0.5% more likely to rate their ability in handling unexpected problems as poor, compared to others. This set of regressions further supports the results of Table 4, regarding the u-shaped relationship between religious involvement and superior mental well-being. Regarding the controls, the explanations provided for Table 4 should be reiterated here.

Discussion

The results reported in Table 3 indicate that the individuals identified as “highly religious” are statistically significantly and non-negligibly more likely to frequently assert that they meaningfully contribute to the society, they belong to a community, and the society improves for people like them, compared to the individuals identified as “secularized”, and the average. They also, more often than others, feel that challenges in life make them better, and life has a direction or meaning. These findings echo previous literature regarding the positive association of religiosity with the accumulation of social capital (Wuthnow 2002; Putnam and Campbell 2010; Yeary et al. 2012), and the greater individualism of the seculars (Bainbridge 2005; Galen and Kloet 2011).

There is a burgeoning scholarship which documents the differences between the religious and a variety of secular groups, in their socioeconomic and health outcomes (Galen 2015; Zuckerman 2009), with special attention devoted to the atheists (Whitley 2010; Hwang 2013). Bainbridge (2005) hypothesizes that lacking social obligations is a source of atheism and notes that the greater individualism of the atheists prevents them from forming strong community ties. Cimino and Smith (2011, 2014) report that in the USA some secular groups have adopted a “subcultural identity”, expressed in their claim that they are an “embattled minority” in a religious and hostile society. Smith (2011, 2013) reports that American seculars believe that they receive little support from either the media or political establishments in maintaining their secular worldview and lifestyle. This strand of literature implies that secular groups may exhibit a diminished sense of belonging to the society and a lower confidence in a societal change to their benefit, as well as deficits in their level of social capital (Putnam and Campbell 2010; Yeary et al. 2012). The results reported in Table 3 are congruent with the assertions made in these studies about American secular groups.

Moreover, in various studies and polls, Americans are found to maintain a negative attitude towards secular groups (Gervais and Norenzayan 2013; Guenther and Mulligan 2013; Pew Research Center 2014). This negative attitude is reported to be pervasive, resulting in the marginalization of the secular minorities (Edgell et al. 2006; Doane and Elliott 2015). There are also reports of generalized mistrust (Gervais et al. 2011) and perceived or actual discrimination (Hunsberger and Altemeyer 2006; Cragun et al. 2012; Hammer et al. 2012), directed towards secular groups. Discrimination is found deleterious to the health and well-being of members of marginalized groups (Pascoe and Smart Richman 2009). Weber et al. (2012), reviewing the literature, confirm that the generally negative perception by others undermines the well-being of members of secular groups. The findings reported in Table 3 attest to the social capital deficits of Canadian seculars. While past literature links social capital to superior mental health outcomes (McKenzie et al. 2002; Almedom 2005), the results in Tables 4 and 5 do not fully support that these deficits have a negative mental well-being impact.

The results reported in Table 4 point to the complexity of the association between religiosity and mental health. The composite patterns revealed from the analysis suggest that there are several mechanisms simultaneously at work, across the population. Both the secular and the highly religious are found more likely than the average to be situated at the two ends of the mental health spectrum. The u-shaped relationship between religiosity and excellent mental health is in accord with a few previous reports (Ross 1990; Diener and Clifton 2002; Riley et al. 2005; Galen and Kloet 2011). This pattern is also compatible with the idea of the salutary effects of having a confirmed worldview, as both of these two groups seem more committed to their worldviews than the individuals with average religiosity (Shaver et al. 1980; Speed and Fowler 2016). Finally, the higher likelihood of secularized individuals reporting excellent mental health can be partially explained by self-selection. The psychosocial characteristics of the seculars may have obviated their need for seeking comfort or explanation in religion (Diener et al. 2011).

The finding that both high religiosity and secularity are stronger predictors of poor mental health has not been previously reported. This pattern is compatible with a number of explanations. The higher likelihood of poor mental health for the highly religious may indicate reverse causation and is compatible with the scholarship which suggests religion as a coping mechanism (Pargament and Park 1997; Pargament et al. 1998; Hess et al. 2014). Individuals facing psychosocial difficulties may resort to religion as means of comfort (Pargament 2002; Diener et al. 2011). The higher likelihood of poor mental health for the secularized is compatible with the previously reviewed literature on their social capital deficits (Putnam and Campbell 2010; Yeary et al. 2012), as well as their marginalization (Edgell et al. 2006; Gervais et al. 2011; Cragun et al. 2012; Doane and Elliott 2015).

As reported in Table 5, both the highly religious and the secularized are found to be more likely to rate their ability to deal with day-to-day demands of life as excellent. This pattern likely reflects their superior mental health outcomes, previously discussed. For the ability to handle unexpected and difficult problems in life, the secularized are found more likely than others to self-report of excellent ability. The highly religious individuals, on the other hand, are slightly more likely to rate their ability as poor. In previous scholarship, people with conservative religious beliefs are suggested to manifest a lower sense of personal control (Schieman 2008; Ellison and Burdette 2012), compared to less religious individuals. Additionally, religiously conservative individuals are suggested to engage in deferred religious coping (Pargament et al. 1988; Maynard et al. 2001), which involves relinquishing control to the divine, during the crises. The patterns regarding the self-rated ability to handle unexpected and difficult problems in life appear consistent with these previous studies, which highlight the inverse relationship between religiosity and the sense of personal control.

The limitations of this analysis must be noted. First, the data set only included a single question allowing the measurement of religious and spiritual involvement. Finer classifications within the highly religious and the secularized groups would have allowed to explore the relationships in more detail, and narrow down the range of explanations provided for the empirical patterns. Second, the outcomes are assessed based on dichotomized self-reports. Several mechanisms can cause systematic biases in self-reported data, such as socially desirable responding (Brenner and Delamater 2014) and identity consistency (Brenner 2011). The possibility that religious and secular individuals have different reference groups when rating their mental health may also have impacted the relative magnitudes of the estimates (Peng et al. 1997; Heine et al. 2002). Finally, due to the paucity of scholarship using Canadian data, the discussions were focused on American patterns, and it remained impossible to integrate the results into a Canadian perspective.

Concluding Remarks

This study used a large and high-quality data set, a straightforward operationalization of the concept of religiosity, and a flexible modelling strategy. Part of the muddle in the literature on the relationship between mental health and religiosity arises from an unclear differentiation between who is religious or spiritual and who is not. In this paper, the population was divided into three segments of highly religious, secularized, and the average, based on a single-item self-report. First, the association of belonging to each of these segments with several psychological markers has been analysed. The analysis revealed that the highly religious and the secularized, as identified in this paper, meaningfully differ from each other in their worldviews. The individuals identified as secularized manifested substantial deficits in the indicators regularly suggested to mediate the relationship between religiosity and mental health, such as community belonging and sensing a direction in life. Further analysis, however, showed that these deficits do not exercise a direct negative impact on mental health outcomes of Canadian seculars.

When the mental health implication of belonging to these groups was considered, a nonlinear composite pattern was revealed. Both the highly religious and the secularized are found more likely than the average to be at the extremities of mental health scale, in Canada. Most previous studies did not incorporate adequate flexibility in the data analysis phase to allow for the detection of such complex patterns. This paper illustrates the intricacy, and perhaps the ambivalence, of the relationship between religious involvement and mental well-being and sheds doubt on the accuracy and currency of a universal positive association. Future research can assess whether these patterns are valid for countries other than Canada.

Notes

The CCHS does not record the religious affiliation of the respondents. However, an examination of other nationally representative data sets, such as the General Social Survey, indicates that excluding immigrants, 95% of the religiously affiliated Canadians belong to a Christian denomination. Therefore, it must be assumed that as far as the religious is concerned, the results obtained in this analysis are informative about the Christian faith.

Other data sources, such as the Canadian General Social Survey, indicate that individuals who report religion is very important to them are largely more likely to be frequent churchgoers, and often engage in religious practices on their own. On the other hand, respondents who report religion is not at all important to them are unlikely to ever attend religious services, and sporadically engage in private religious practices.

References

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5(4), 432–443.

Almedom, A. M. (2005). Social capital and mental health: An interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. Social Science and Medicine, 61(5), 943–964.

Baetz, M., Griffin, R., & Marcoux, R. B. G. (2004). Spirituality and psychiatry in Canada: Psychiatric practice compared with patient expectations. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(4), 265–271.

Bainbridge, W. S. (2005). Atheism. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion, 1(2), 1–26.

Baker, P., & Cruickshank, J. (2009). I am happy in my faith: The influence of religious affiliation, saliency, and practice on depressive symptoms and treatment preference. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 12(4), 339–357.

Bradley, D. E., & Roberts, J. A. (2004). Self-employment and job satisfaction: Investigating the role of self-efficacy, depression, and seniority. Journal of Small Business Management, 42(1), 37–58.

Brenner, P. S. (2011). Identity importance and the overreporting of religious service attendance: Multiple imputation of religious attendance using the American Time Use Study and the General Social Survey. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 50(1), 103–115.

Brenner, P. S., & DeLamater, J. D. (2014). Social desirability bias in self-reports of physical activity: Is an exercise identity the culprit? Social Indicators Research, 117(2), 489–504.

Buggle, F., Bister, D., Nohe, G., et al. (2001). Are atheists more depressed than religious people? A new study tells the tale. Free Inquiry, 20(4), 50–54.

Cimino, R., & Smith, C. (2011). The new atheism and the formation of the imagined secularist community. Journal of Media and Religion, 10(1), 24–38.

Cimino, R., & Smith, C. (2014). Atheist awakening: Secular activism and community in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cragun, R. T., Kosmin, B., Keysar, A., Hammer, J. H., & Nielsen, M. (2012). On the receiving end: Discrimination toward the non-religious in the United States. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 27(1), 105–127.

Diener, E., & Clifton, D. (2002). Life satisfaction and religiosity in broad probability samples. Psychological Inquiry, 13(3), 206–209.

Diener, E., Tay, L., & Myers, D. G. (2011). The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1278–1290.

Dilmaghani, M. (2016). Religiosity and subjective wellbeing in Canada. Journal of Happiness Studies. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9837-7.

Doane, M. J., & Elliott, M. (2015). Perceptions of discrimination among atheists: Consequences for atheist identification, psychological and physical well-being. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 7(2), 130–141.

Eagle, D. E. (2011). Changing patterns of attendance at religious services in Canada, 1986–2008. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 50(1), 187–200.

Edgell, P., Gerteis, J., & Hartmann, D. (2006). Atheists as ‘‘other:’’ Moral boundaries and cultural membership in American society. American Sociological Review, 71(2), 211–234.

Eliassen, A. H., Taylor, J., & Lloyd, D. A. (2005). Subjective religiosity and depression in the transition to adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 44(2), 187–199.

Ellison, C. G., & Burdette, A. M. (2012). Religion and the sense of control among US adults. Sociology of Religion, 73(1), 1–22.

Ellison, C. G., Burdette, A. M., & Hill, T. D. (2009). Blessed assurance: Religion, anxiety, and tranquility among US adults. Social Science Research, 38(3), 656–667.

Ellison, C. G., & Lee, J. (2010). Spiritual struggles and psychological distress: Is there a dark side of religion? Social Indicators Research, 98(3), 501–517.

Ellison, C. G., & Levin, J. S. (1998). The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education and Behavior, 25(6), 700–720.

Frankel, B. G., & Hewitt, W. E. (1994). Religion and well-being among Canadian university students: The role of faith groups on campus. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 33(1), 62–73.

Galek, K., Krause, N., Ellison, C. G., Kudler, T., & Flannelly, K. J. (2007). Religious doubt and mental health across the lifespan. Journal of Adult Development, 14(1/2), 16–25.

Galen, L. (2015). Atheism, wellbeing, and the wager: Why not believing in God (with others) is good for you. Science, Religion and Culture, 2(3), 54–69.

Galen, L. W., & Kloet, J. D. (2011). Mental well-being in the religious and the non-religious: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 14(7), 673–689.

Gee, E. M., & Veevers, J. E. (1990). Religious involvement and life satisfaction in Canada. Sociology of Religion, 51(4), 387–394.

Gervais, W. M. (2011). Finding the faithless: Perceived atheist prevalence reduces anti-atheist prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(4), 543–556.

Gervais, W. M., & Norenzayan, A. (2013). Religion and the origins of anti-atheist prejudice. In S. Clarke, R. Powell, & J. Savulescu, (Eds.), Intolerance and conflict: A scientific and conceptual investigation (pp. 126–145). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Gervais, W. M., Shariff, A. F., & Norenzayan, A. (2011). Do you believe in atheists? Distrust is central to anti-atheist prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1189–1206.

Gill, R., Hadaway, C. K., & Marler, P. L. (1998). Is religious belief declining in Britain?. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37(3), 507–516.

Guenther, K. M., & Mulligan, K. (2013). From the outside in: Crossing boundaries to build collective identity in the new atheist movement. Social Problems, 60(4), 457–475.

Hackney, C. H., & Sanders, G. S. (2003). Religiosity and mental health: A meta-analysis of recent studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(1), 43–55.

Hammer, J., Cragun, R., Hwang, K., & Smith, J. (2012). Forms, frequency, and correlates of perceived anti-atheist discrimination. Secularism and Nonreligion, 1, 43–67.

Hay, D. A. (2014). An investigation into the swiftness and intensity of recent secularization in Canada: Was berger right? Sociology of Religion, 75(1), 136–162.

Hayward, R. D., Krause, N., Ironson, G., Hill, P. C., & Emmons, R. (2016). Health and well-being among the non-religious: Atheists, agnostics, and no preference compared with religious group members. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(3), 1024–1037.

Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Peng, K., & Greenholtz, J. (2002). What’s wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales? The reference-group effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 903–918.

Hess, R. E., Maton, K. I., & Pargament, K. (2014). Religion and prevention in mental health: Research, vision, and action. London: Routledge.

Hill, P. C., & Pargament, K. I. (2008). Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, S(1), 3–17.

Hill, P. C., Pargament, K. I., Hood, R. W., McCullough Jr, M. E., Swyers, J. P., Larson, D. B., & Zinnbauer, B. J. (2000). Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 30(1), 51–77.

Hogg, M. A., Adelman, J. R., & Blagg, R. D. (2010). Religion in the face of uncertainty: An uncertainty-identity theory account of religiousness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 72–83.

Horning, S. M., Davis, H. P., Stirrat, M., & Cornwell, R. E. (2011). Atheistic, agnostic, and religious older adults on well-being and coping behaviors. Journal of Aging Studies, 25(2), 177–188.

Hout, M., & Fischer, C. S. (2002). Why more Americans have no religious preference: Politics and generations. American Sociological Review, 67(2), 165–190.

Hunsberger, B. (1985). Religion, age, life satisfaction, and perceived sources of religiousness: A study of older persons. Journal of Gerontology, 40(5), 615–620.

Hunsberger, B. E., & Altemeyer, B. (2006). Atheists: A groundbreaking study of America’s nonbelievers. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

Hwang, K. (2013). Atheism, health, and well-being. In S. Bullivant, & M. Ruse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of atheism. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199644650.013.019.

Hwang, K., Hammer, J. H., & Cragun, R. T. (2011). Extending religion-health research to secular minorities: Issues and concerns. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(3), 608–622.

Iannaccone, L. R. (1992). Sacrifice and stigma: Reducing free-riding in cults, communes, and other collectives. Journal of Political Economy, 100(2), 271–291.

Iannaccone, L. R. (1994). Why strict churches are strong. American Journal of Sociology, 99(5), 1180–1211.

Idler, E. L. (1987). Religious involvement and the health of the elderly: Some hypotheses and an initial test. Social Forces, 66(1), 226–238.

Johnson, M. K., Rowatt, W. C., & LaBouff, J. (2010). Priming Christian religious concepts increases racial prejudice. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1(2), 119–126.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1982). Variants of uncertainty. Cognition, 11(2), 143–157.

Koenig, H. G. (1995). Religion as cognitive schema. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 5(1), 31–37.

Koenig, H. G. (2008). Concerns about measuring “spirituality” in research. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(5), 349–355.

Koenig, H., King, D., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Koenig, G. H., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Religion and mental health: Evidence for an association. International Review of Psychiatry, 13(2), 67–78.

Krause, N. (2011). Religion and health: Making sense of a disheveled literature. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(1), 20–35.

Krause, N., Chatters, L. M., Meltzer, T., & Morgan, D. L. (2000). Negative interaction in the church: Insights from focus groups with older adults. Review of Religious Research, 41(4), 510–533.

Krause, N., & Hayward, R. D. (2012a). Religion, meaning in life, and change in physical functioning during late adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 19(3), 158–169.

Krause, N., & Hayward, R. D. (2012b). Humility, lifetime trauma, and change in religious doubt among older adults. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(4), 1002–1016.

Krause, N., & Wulff, K. M. (2004). Religious doubt and health: Exploring the potential dark side of religion. Sociology of Religion, 65(1), 35–56.

LeDrew, S. (2013). Discovering atheism: Heterogeneity in trajectories to atheist identity and activism. Sociology of Religion, 74(4), 431–453.

Levin, J. S., & Chatters, L. M. (1998). Religion, health, and psychological well-being in older adults, findings from three national surveys. Journal of Aging and Health, 10(4), 504–531.

Lochner, K., Kawachi, I., & Kennedy, B. P. (1999). Social capital: A guide to its measurement. Health and Place, 5(4), 259–270.

Lyon, D., & Van Die, M. (2000). Rethinking church, state, and modernity: Canada between Europe and America. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Maselko, J., Gilman, S. E., & Buka, S. (2009). Religious service attendance and spiritual well-being are differentially associated with risk of major depression. Psychological Medicine, 39(6), 1009–1017.

Maynard, E., Gorsuch, R., & Bjorck, J. (2001). Religious coping style, concept of God, and personal religious variables in threat, loss, and challenge situations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40(1), 65–74.

McKenzie, K., Whitley, R., & Weich, S. (2002). Social capital and mental health. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181(4), 280–283.

Millán, J. M., Hessels, J., Thurik, R., & Aguado, R. (2013). Determinants of job satisfaction: A European comparison of self-employed and paid employees. Small Business Economics, 40(3), 651–670.

Muntaner, C., Ng, E., Vanroelen, C., Christ, S., & Eaton, W. W. (2013). Social stratification, social closure, and social class as determinants of mental health disparities. In C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 205–227). Amsterdam: Springer.

Nielsen, M. E. (1998). An assessment of religious conflicts and their resolutions. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37(1), 181–190.

Norenzayan, A., & Gervais, W. M. (2015). Secular rule of law erodes believers’ political intolerance of atheists. Religion, Brain and Behavior, 5(1), 3–14.

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A. (2010). Religiosity and life satisfaction across nations. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 13(2), 155–169.

Pargament, K. I. (2002). Is religion nothing but…? Explaining religion versus explaining religion away. Psychological Inquiry, 13(3), 239–244.

Pargament, K. I., Kennell, J., Hathaway, W., Grevengoed, N., Newman, J., & Jones, W. (1988). Religion and the problem-solving process: Three styles of coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 27(1), 90–104.

Pargament, K. I., & Park, C. L. (1997). In times of stress: The religion-coping connection. In B. Spilka & D. N. McIntosh (Eds.), The psychology of religion: Theoretical approaches (pp. 43–53). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. (xii, 282 pp).

Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37(4), 710–724.

Pascoe, E. A., & Smart Richman, L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531–554.

Peng, K., Nisbett, R. E., & Wong, N. Y. (1997). Validity problems comparing values across cultures and possible solutions. Psychological Methods, 2(4), 329–344.

Pew Research Center. (2014). For 2016 hopefuls, WA experience could do more harm than good. Available at: http://www.people-press.org/files/legacy-pdf/5-19-14%20Presidential%20Traits%20Release.pdf.

Putnam, R. D., & Campbell, D. E. (2010). American grace. How religion divides and unites us. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Riley, J., Best, S., & Charlton, B. G. (2005). Religious believers and strong atheists may both be less depressed than existentially-uncertain people. Quarterly Journal of Medicine, 98(11), 840.

Rosenfield, S., & Mouzon, D. (2013). Gender and mental health. In C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 277–296). Amsterdam: Springer.

Ross, C. E. (1990). Religion and psychological distress. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 29(2), 236–245.

Salsman, J. M., Brown, T. L., Brechting, E. H., & Carlson, C. R. (2005). The link between religion and spirituality and psychological adjustment: The mediating role of optimism and social support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(4), 522–535.

Schieman, S. (2008). The religious role and the sense of personal control. Sociology of Religion, 69(3), 273–296.

Schnittker, J. (2001). When is faith enough? The effects of religious involvement on depression. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40(3), 393–411.

Shaver, P., Lenauer, M., & Sadd, S. (1980). Religiousness, conversion, and subjective well-being: The “healthy-minded” religion of modern American women. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137(5), 1563–1568.

Sherkat, D. E., & Ellison, C. G. (1999). Recent developments and current controversies in the sociology of religion. Annual Review of Sociology, 25, 363–394.

Silton, N. R., Flannelly, K. J., Galek, K., & Ellison, C. G. (2014). Beliefs about God and mental health among American adults. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(5), 1285–1296.

Smith, J. M. (2011). Becoming an atheist in America: Constructing identity and meaning from the rejection of theism. Sociology of Religion, 72(2), 215–237.

Smith, J. M. (2013). Creating a godless community: The collective identity work of contemporary American atheists. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 52(1), 80–99.

Smith-Stoner, M. (2007). End-of-life preferences for atheists. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 10(4), 923–928.

Speed, D., & Fowler, K. (2016). What’s God got to do with it? How religiosity predicts atheists’ health. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(1), 296–308.

Stark, R., & Maier, J. (2008). Faith and happiness. Review of Religious Research, 50(1), 120–125.

Statistics Canada. (2013). Canadian Community Health Survey—Mental Health (CCHS) (Data Guide). Available at: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5015.

Strawbridge, W. J., Cohen, R. D., Shema, S. J., & Kaplan, G. A. (1997). Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. American Journal of Public Health, 87(6), 957–961.

Suh, E. M. (2002). Culture, identity consistency, and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1378.

Thiessen, J., & Dawson, L. L. (2008). Is there a” renaissance” of religion in Canada? A critical look at Bibby and beyond. Studies in Religion, 37(3/4), 389–415.

Vail, K. E., Rothschild, Z. K., Weise, D. R., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., & Greenberg, J. (2010). A terror management analysis of the psychological functions of religion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 84–94.

Weber, S. R., Pargament, K. I., Kunik, M. E., Lomax, J. W., II, & Stanley, M. A. (2012). Psychological distress among religious nonbelievers: A systematic review. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(1), 72–86.

Whitley, R. (2010). Atheism and mental health. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 18(3), 190–194.

Wilkins-Laflamme, S. (2015). How unreligious are the religious nones? Religious dynamics of the unaffiliated in Canada. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 40(4), 477–500.

Wilkinson, P. J., & Coleman, P. G. (2010). Strong beliefs and coping in old age: A case-based comparison of atheism and religious faith. Ageing and Society, 30(02), 337–361.

Wuthnow, R. (2002). Religious involvement and status-bridging social capital. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41(4), 669–684.

Yeary, K. H. C. K., Ounpraseuth, S., Moore, P., Bursac, Z., & Greene, P. (2012). Religion, social capital, and health. Review of Religious Research, 54(3), 331–347.

Zuckerman, P. (2009). Atheism, secularity, and well-being: How the findings of social science counter negative stereotypes and assumptions. Sociology Compass, 3(6), 949–971.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals, performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dilmaghani, M. Importance of Religion or Spirituality and Mental Health in Canada. J Relig Health 57, 120–135 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0385-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0385-1