Abstract

Like that of other normative behaviors, much of the research on physical exercise is based on self-reports that are prone to overreporting. While research has focused on identifying the presence and degree of overreporting, this paper fills an important gap by investigating its causes. The explanation based in impression management will be challenged, using an explanation based in identity theory as an arguably better fitting alternative. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: (1) a web instrument using direct survey questions, or (2) a chronological reporting procedure using text messaging. Comparisons to validation data from a reverse record check indicate significantly greater rates of overreporting in the web condition than in the text condition. Results suggest that measurement bias is associated with the importance of the respondents’ exercise identity, prompted by the directness of the conventional survey question. Findings call into question the benefit of self-administration for bias reduction in measurement of normative behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The relationship between physical activity and health is positive and strong. Therefore, policies that advocate health-promoting behaviors, like exercise, are important for encouraging the physical health of individuals in our society (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2008). However, good health policy decisions depend on accurate information, and accurate information depends on good measures. According to Washburn et al., “the task of determining effective interventions for promoting adoption and maintenance of healthful physical activity behaviors will be impossible without reliable and valid measurements of the dependent variable, physical activity” (2000, p. 105). Accordingly, the accurate measurement of these activities has become essential for effective policy creation and implementation.

Much of the extant research on the relationship between physical activity and health is based on self-reports, typically gathered through survey research. However, similar to other normative behaviors like church attendance (see Chaves and Stephens 2003 for a review) and voting (Bernstein et al. 2001), physical exercise is often overreported (Sallis and Saelens 2000). Respondents report higher rates or more frequent activity on surveys than actual behavior warrants, leading questionnaire measures of physical activity to suffer from low validity (Durante and Ainsworth 1996; Shephard 2003).

Epidemiologists have tested the validity of questionnaire measures of physical activity using objective physical measures as a comparator. These objective physical comparators have included percentage of body fat (Ainsworth et al. 1993), exercise performance data recorded by equipment like treadmills, accelerometers and actigraphs (Adams et al. 2005; Jacobs et al. 1993; Leenders et al. 2001; Matthews et al. 2000; Matthews and Freedson 1995; Taylor et al. 1984), an estimation of metabolic rate using doubly labeled water (Adams et al. 2005), and an estimation of energy expenditure from the caloric intake of a controlled feeding program (Albanes et al. 1990). These comparators, each with its own validity problems (see Bassett 2000; Williams et al. 1989) may be better described as evidence of convergent rather than criterion validity (Patterson 2000; see also Washburn et al. 2000) as none compare a self-report of physical exercise with validation data for the same activity. Rather, each compares a survey self-report with potential evidence, of varying quality, of that activity.

Other work has utilized methods and data more common to the social sciences, like flexible interviewing techniques, direct observation, and reverse record checks to estimate the validity of self-reports. Suspecting a high amount of overreporting, Rzewnicki et al. (2003) reinterviewed a random subsample of survey respondents using a more detailed set of probes. The reinterview uncovered high levels of overreporting that were attributed to problems in interviewing and question comprehension in the initial interview (see also Baranowski 1988; Durante and Ainsworth 1996). Using direct but unobtrusive observation, Klesges et al. (1990) found that respondents who reported high levels of habitual physical activity showed the greatest level of divergence between their self-reported and actual levels of activity during the reference period. Chase and Godbey (1983) asked members of a tennis club and a swimming club to estimate the frequency of their past use of the club’s facilities and compared these self-reports to sign-in sheets. In both clubs, they found that over 75 % of respondents overestimated their participation in club activities.

While these projects have been very informative in their primary focus on identifying the presence and degree of overreporting, very few studies have attempted to explain its causes. Comparing objective physical measures (e.g., accelerometer data, estimates of energy expenditure) to a series of physical activity recalls, Adams et al. (2005) tested the Martin-Larson Approval Motivation Scale and the Crowne-Marlow Social Desirability Scale as predictors of overreporting. They found that social approval was not strongly associated with overreporting and that the relationship between social desirability and overreporting was inconsistent. Motl et al. (2005) too found only a minimal influence of social desirability on self-reported physical activity. However, their lack of a criterion measure limited analysis to self-reports rather than to estimates of overreporting, adding a major caveat to their inferences.

In summary, while the existence of the phenomenon is well established, very little research has explored the causes of overreporting of physical exercise on surveys, and the literature that does exist fails to consistently and persuasively explain why overreporting occurs. Moreover, previous research has found that the hypothesized positive relationship between overreporting and social desirability is either weak and inconsistent, or nonexistent. This project aims to fill in this gap in the extant literature by investigating the causes of overreporting of physical activity. In so doing, the currently accepted explanation of social desirability effects for the overreporting of normative behaviors based in impression management theory is challenged, using an explanation based in identity theory (Stryker 1980/2003) as an arguably better fitting alternative.

1.1 Social Desirability Effect: Impression Management or an Identity Process?

The cognitive model of survey response (Cannell et al. 1977, 1981; Tourangeau 1984; Tourangeau et al. 2000) established a set of steps for the response process, allowing survey methodologists to further pursue the “total survey error” approach (Groves 1989/2004; Weisberg 2005) and identify the sources of error in the survey process. The final two stages of the process, judgment and response, are generally viewed as those in which social desirability effects—the intentional misreporting of sensitive behaviors—emerge. For example, respondents tend to underreport contranormative, sensitive, or embarrassing behaviors (e.g., illicit drug use and other illegal activity) and overreport normative or positively viewed behaviors (e.g., voting, church attendance, and physical exercise). In its common formulation, the respondent misreports behavior in order to manage the impression s/he is presenting to the interviewer. Therefore, removing the interviewer from the measurement process by using self-administered questionnaires is generally accepted as a means to achieve more valid reports of sensitive behaviors (Aquilino and LoSciuto 1990).

While evidence in the literature is strongly supportive of impression management as a cause of underreporting of contranormative behavior, comparatively little research has tested its application to the overreporting of normative behaviors. If impression management is driving overreporting of normative behavior in interviewer-administered modes, we should see a reduction in overreporting when comparing interviewer- and self-administered modes from comparable samples (e.g., random subsamples) of respondents. However, the few existing tests of this assumption have yielded mixed findings (Kreuter et al. 2008; Stocké 2007).

An alternative explanation focuses on the respondent’s identity. Identity theory (Stryker 1980) contributes two concepts that are useful for understanding the difference between these two modes of survey measurement. Importance is the “personal value individuals place on an identity (that) taps into subjective feelings of what is central to individuals’ conceptions of themselves” (Ervin and Stryker 2001: 34–5). While a respondent is aware of the importance s/he places on an identity, s/he does not necessarily know how likely s/he is to perform that identity. This second concept of identity theory, salience, is the probability of an identity being invoked within a situation (Stryker 1980) or the propensity to define a situation in a way as to provide an opportunity to perform that identity (Stryker and Serpe 1982).

While self-reported levels of importance and salience of an identity are often consistent, they need not be. Congruence may be an artifact of measurement (Stryker and Serpe 1994). The process of measuring the salience of an important identity may inflate the self-report of salience to match the importance of the identity. Moreover, the directive nature of survey measurement makes it difficult to conceive of a measure of identity salience that does not prime the identity, encouraging the alignment of importance and salience, and affecting the process of measurement (Ervin and Stryker 2001; Stryker and Burke 2000). Such a situation is especially problematic for the measurement of an important, but rarely enacted, identity (Burke 1980).

Unlike conventional survey questions, chronologically based data collection procedures, like time diaries, avoid much of the biasing effect of identity importance (Bolger et al. 2003). By eschewing direct questions about specific behaviors of interest (Robinson 1985, 1999; Stinson 1999), chronological data collection procedures avoid prompting self-reflection on the part of the respondent, arguably yielding less biased and higher quality data on many normative behaviors (Bolger et al. 2003; Niemi 1993; Zuzanek and Smale 1999).

The following analyses predict overreporting of physical exercise, computed as the positive difference between self-reported and “gold standard” measures of behavior, using a measure of identity importance and measurement condition (i.e., the measurement of salience using either a direct survey question or a nondirective chronological reporting procedure) as predictors. The gold standard validation measure—a reverse record check of admission records to recreation facilities—is treated here as the true value of salience; the actual propensity of identity enactment during the reference period. The two self-reported measures (which will be described shortly) are observations of this true value of varying quality. A conventional survey self-report is hypothesized to be a biased measure of the true value with the bias arguably caused by identity importance. However, the novel chronological reporting procedure is expected to produce a relatively unbiased measure of the true value. Including both identity and method of measurement provides a test of a main assumption of this application of identity theory to survey responding on normative behavior.

2 Data and Methods

A random sample of undergraduates from a large Midwestern university were invited to participate in a survey of daily life conducted in March and April 2011. While other sampling designs could potentially increase external validity, they also present significant complications. A frame covering the general adult population (e.g., an address-based sample) would necessitate gaining access to records from numerous recreation facilities, making such a design difficult, if not untenable. Alternatively, using membership rolls from a sample of recreation facilities (for-profit gyms and non-profit or community fitness centers like the Y and city or county owned recreation centers) as a sampling frame would encounter selection biases, as selection into the frame (i.e., joining the gym) is likely strongly correlated to outcome measures used here.Footnote 1 However, students at the selected university automatically have access to the university’s recreation facilities, making them inadvertent gym members. A random sample from the list frame of enrolled students provided by the bursar essentially allowed the sampling of gym members without the selection biases in other potential designs.

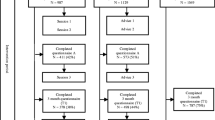

A random sample of 600 undergraduates, stratified by gender and year in school, was divided into two subsamples: 275 were assigned to Condition 1 and invited to take a web survey; 325 were assigned to Condition 2 and were invited to take a similar web survey followed up by five days of data collection via SMS/text messaging. The invitation to participate in the study was sent to the student’s university email address, including a link to the web survey. An email reminder to complete the survey was sent three days after the initial invitation, and a final reminder was sent five days after the first reminder email. Participants in both conditions were offered a ten dollar incentive following completion of the web survey. Participants in Condition 2 were offered an additional 30 dollars following completion of the text component of the study.

The web survey in both conditions was comprised of approximately twenty questions about usage of university facilities. While the true purpose of the study was to measure use of university recreation facilities, “nuisance” questions about the use of campus libraries, the student union, and other university facilities were also asked in order to mask the focus of the study. In Condition 1, measurement of the focal behavior, physical exercise, used a conventional survey question in the context of the questions about use of other university facilities. Respondents were asked to report (1) the number of days in the past seven in which they exercised and (2) on how many of these days, if any, their exercise activity occurred at a campus recreational facility.

In lieu of being asked this direct survey question, respondents in Condition 2 were asked to send SMS/text messages to the research team reporting all changes in their major activities for a period of five days. Respondents received training documents detailing how and what activities they should report, including, but not highlighting, the focal behavior. The list of examples included: attending classes, studying and doing homework, going to the library, eating/dining on or off campus, participating in meetings and organizations, attending or performing in entertainment or cultural activities, running errands and doing chores, and engaging in sports and exercise.

The texting procedure differs from related methods in key ways. First, unlike the Experience Sampling Method (ESM), which collects data from subjects only at random prompts (Csikszentmihalyi and Larson 1987), respondents in the texting procedure were asked to text updates on all of their major activities as they occurred. Respondents were reminded multiple times each day, more frequently on the first day of their participation (four reminders, at 10:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., 5:00 p.m., and 8:00 p.m.) and less frequently on the final days of participation (two reminders, at 10:00 a.m. and 8:00 p.m.). Second, unlike many related calendar and diary procedures, the texting procedure was completely in situ, minimizing the problems associated with retrospective reporting (e.g., memory, reflection). Moreover, the texting procedure was completely self-administered without any other interviewer involvement (e.g., collecting completed diaries, checking over the diary with the respondent). Condition 2 respondents sent an average of 22 messages (range = 2–59; SD = 10.8) over the field period, averaging about five per day. The frequency and other characteristics of the text message activity updates suggest that these data are of high quality (Brenner and DeLamater 2013).

After all other participation was completed, respondents in both conditions were asked for their student identification numbers so that study staff could request records on their use of campus recreation facilities. These records are the product of the swiping of students’ identification cards upon admission to the facilities. This process records the student’s identification number and the time and day of admittance to the facility.

Prior to the field period, direct but unobtrusive field observation was employed at recreation facilities to ensure the quality of these record data. During the periods of observation, all entrants to the recreation facilities had their student ID cards scanned. Without exception, every entrant proceeded to engage in exercise activities or sports, although many first stopped briefly to change into workout clothes in a locker room. This preliminary work further establishes the quality of facility access records as criterion measure.

The response rate varied between conditions. 124 respondents in each condition completed the web questionnaire, yielding an overall response rateFootnote 2 of 41.3 %; 45.1 % in Condition 1 and 38.2 % in Condition 2. In Condition 1, 89 respondents granted access to their record data, yielding a compliance rate of 71.8 % and a final response rate in this condition of 32.4 %. In Condition 2, 87 respondents completed the texting component. Of those, 67 permitted access to their record data, yielding a compliance rate of 77.0 % and final response rate of 22.8 % in this condition.

2.1 Measures

Three key variables are used in the following analyses. The first is a measure of the validity of the self-report, computed as the difference between the reverse record check and the respondent’s self-report. Each day with a record of admittance to a campus recreation facility during the reference period was coded as 1, 0 otherwise. This procedure yielded a series of variables, one for each day, each coded for the presence or absence of an admittance. These were summed to reflect the number of days during the reference period that the respondent used campus recreation sports facilities.

In each condition, this variable was subtracted from the self-report to create the measure of the validity of the self-report. In Condition 1, the record check variable was compared to a direct survey question asking specifically about the frequency of campus recreational sports facilities use during the reference period: “Of the days you worked out in the past week, how many did you use (University Name) Recreational Sports facilities, like (names of facilities)?”Footnote 3 In Condition 2, respondents reported changes in their major activities during the reference period using SMS/text messages. Each day with a report of exercise at a campus recreation sports facility was coded as 1, 0 otherwise. This variable was then summed over the days of the reference period.

In both conditions, the difference between the self-report (S) and the record check (R) resulted in nominal variable categorizing respondents (see Table 1):

-

1.

If S = R = 0, the respondent is an admitted nonexerciser,

where S is the number of days the respondent reports exercising at campus recreation facilities during the reference period and R is the number of days the respondent entered campus recreation facilities given record data.

-

2.

If (S > 0) = R, the respondent is a validated exerciser.

-

3.

If S < R, the respondent is an underreporter.Footnote 4

-

4.

If S > R, the respondent is an overreporter.

The category of overreporter can be further distinguished into two subcategories.

-

5.

If S > (R = 0), the respondent is a non-exercising overreporter.

-

6.

If S > (R > 0), the respondent is an exercising overreporter.

This categorical variable is used as an outcome variable in the first analysis, and a grouping variable in the second analysis.

The second variable is a measure of the importance of a physical exercise identity. Respondents in both conditions were asked in the web survey a battery of eight questions about the importance of a set of identities common amongst college students (e.g., one’s role as a student, belonging to his or her family, membership in an organization, being a (boy/girl)-friend or spouse). For physical exercise, the question read: “Each of us is involved in various activities. How important to you is: playing sports, exercising, or working out?” Identity importance was measured using a five-point scale from “not at all important” to “extremely important.” Nearly two-thirds of the respondents reported that an exercise identity was very or extremely important.

The final variable is a dichotomous indicator of the condition: respondents randomly assigned to Condition 1, measuring physical activity with a direct survey question, are coded 1, and those randomly assigned to Condition 2, measuring physical activity with the text message procedure, are coded 0.

2.2 Analysis Plan

Two hypotheses are tested. First, overreporting is hypothesized to be less likely to occur in Condition 2 (compared with Condition 1) because the texting procedure measures exercise without asking a direct survey question. Differences in the rates of overreporting between the two conditions are tested for significance using a Chi square test.

Second, the effect of importance is hypothesized to cause, or at least be associated with, overreporting. This hypothesis is tested using two group comparisons between subgroups of respondents. The first comparison focuses on respondents who report having exercised (i.e., S > 0). If identity importance prompts an affirmative self-report, regardless of actual behavior, no difference in importance ratings should emerge between the two groups of self-reported exercisers: validated exercisers and overreporters. The second comparison focuses on respondents whose records indicate that they did not visit campus recreation facilities during the reference period (i.e., R = 0). If identity importance prompts the self-report of exercise, a difference in the reported importance of an exercise identity should emerge when the two groups of non-exercisers are compared: overreporters should report a higher level of identity importance compared to admitted non-exercisers. The Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon (MWW) test is used to compare the distribution of the ordinal identity importance ratings across subgroups of respondents.

3 Results

As hypothesized, overreporting emerged in Condition 1, and at a much higher rate than in Condition 2 (see Table 2). Almost half (43/89) of the respondents in Condition 1 overreported their frequency of exercise. Moreover, of the Condition 1 respondents who claimed exercise in the past week (63), over two-thirds overreported. Conversely, the rate of overreporting in Condition 2 was negligible. Only seven Condition 2 respondents (of 67) overreported their exercise, identical to the rate of underreporting in this condition.

The difference in the rate of overreporting between conditions is large and highly statistically significant whether the rate of overreporting is compared for all respondents (χ2(1) = 25.2; p ≤ 0.001) or only for self-reported exercisers,(χ2(1) = 13.7; p ≤ 0.001). Together these findings suggest that Condition 1 is severely affected by measurement bias but that measurement error in Condition 2 is randomly distributed.

The next set of analyses addresses the second hypothesis comparing the ratings of exercise identity importance from overreporters to those from other respondents.Footnote 5 The first compares the identity importance ratings of the two groups of self-reported exercisers: overreporters and validated exercisers. Both of these groups of respondents rate the importance of their exercise identity highly, means falling just above “very important.” No substantive difference emerges between overreporters and validated exercisers for the full sample \( \left( {\Updelta_{{{\bar{\text{Y}}}}} = 0.0} \right) \) or in Condition 1 only \( \left( {\Updelta_{{{\bar{\text{Y}}}}} = 0.2} \right) \). Using an MWW test, the null hypothesis of equality of the distributions of identity ratings between validated exercisers and overreporters cannot be rejected for either the full sample (z = −0.57; p = 0.57) or for only Condition 1 respondents (z = 1.04; p = 0.30) (see Table 3).Footnote 6

The second comparison looks for a difference in the identity importance ratings between overreporters and admitted non-exercisers. Overreporters rate the importance of their exercise identity higher than do admitted non-exercisers in the full sample \( \left( {\Updelta_{{{\bar{\text{Y}}}}} = 0.7} \right) \) and in Condition 1 \( \left( {\Updelta_{{{\bar{\text{Y}}}}} = 0.4} \right) \). Using MWW, the null hypothesis of the equality of these distributions is rejected for the full sample (z = −3.81; p ≤ 0.001) and for Condition 1 only (z = −2.07; p ≤ 0.05). While this finding supports the hypotheses based in identity theory, some further analysis may be enlightening.

Overreporters, as currently categorized, are not necessarily non-exercisers. Rather, about half of the respondents in this group actually engaged in some exercise but overreported its frequency. An illustrative comparison juxtaposes the two groups of non-exercisers: non-exercising overreporters and admitted non-exercisers (see Table 1). The identity-based hypotheses anticipate that non-exercisers with high exercise identity importance will have a higher propensity to overreport, which is exactly what is found here. Non-exercising overreporters rate the importance of their exercise identity much higher than do admitted non-exercisers in both the full sample \( \left( {\Updelta_{{{\bar{\text{Y}}}}} = 1.0} \right) \) and in Condition 1 only \( \left( {\Updelta_{{{\bar{\text{Y}}}}} = 0.6} \right) \). Again using MWW, the null hypothesis of equality of these distributions is rejected for both the full sample (z = −4.17; p ≤ 0.001) and Condition 1 respondents only (z = −2.66; p ≤ 0.01).

4 Discussion

The first hypothesis, that the direct survey measure of exercise promotes overreporting, is strongly supported. Respondents in the Condition 1 are much more likely to overreport their exercise frequency than are respondents in Condition 2. Arguably, the text-based chronological reporting procedure allows for the measurement of exercise without the bias inherent in direct survey question because it avoids engaging the respondent’s exercise identity to the same extent as the conventional survey question.

This finding casts doubt on the assertion that self-administered modes yield valid reports of normative behaviors. It demonstrates that a direct survey question, even in a self-administered mode, can lead to dramatic levels of overreporting. Nearly half of the respondents and over two-thirds of self-reported exercisers in Condition 1 overreported. In contrast, the negligible rate of overreporting in Condition 2 appears to be the result of random variation. While the current project only compares two self-administered modes and does not permit comparison to interviewer-administered data, it is difficult to imagine that the presence of an interviewer could produce substantially more biased responses than those found in Condition 1. Arguably, it is the direct survey question that, regardless of the mode in which it is administered, causes much of the bias in the measurement of normative behaviors. Clearly, further testing of this is an excellent opportunity for future research.

The second hypothesis, that identity importance is associated with overreporting, is also supported. According to identity theory, the importance of an identity can bias the measurement of its salience. The salience of an identity of high importance may be overreported if these two concepts become conflated during the measurement process (Stryker and Serpe 1994). It has been argued that direct survey measurement promotes this conflation of importance and salience (Brenner 2011; Burke 1980) and it appears that just such a situation may have occurred here. Ratings of exercise identity importance are higher for overreporters compared to admitted non-exercisers but do not differ from those of verified exercisers.

Survey questions about behavior typically request that the respondent recall relevant information and then either enumerate (i.e., count instances of the behavior during a reference period) or estimate (i.e., apply a rate based on recent behavior recalled from memory, a notion of one’s “typical” behavior, or using other easily accessible information about one’s behavioral patterns) to arrive at an answer. The direct survey question in the web condition calls for enumeration using the past week as the reference period. The respondent is asked to search his or her memory for instance of the focal behavior during the reference period, sum up the occurrences, and report an answer. However, multiple opportunities for error arise in this procedure. First, the respondent may honestly misremember which days s/he went to the campus recreation facilities or inaccurately sum these occurrences. These unintentional errors should be stochastic, with a mean of zero, and just as likely to yield an underreport as an overreport. While this explanation fits Condition 2, random response error does not explain the findings in Condition 1.

Second, the respondent may correctly remember and sum these occurrences, but may choose to edit this actual rate of behavior before reporting it. This type of motivated misreport would likely be caused by the more conventional notion of social desirability (e.g., “I want the interviewer to think that I’m a health-conscious person”). Alternatively, the respondent may either be unable to recall his/her actual behavior over the reference period, or unwilling to put forward the cognitive resources to generate an accurate count (i.e., cognitive missing), either situation yielding estimation rather than enumeration. In this third case, identity is a prime suspect as a cause for the misestimation.

While these findings are not definitive in teasing apart these two different, yet related, explanations, they do suggest that the third possibility is likely and that identity has a primary role to play in promoting an overreport. A series of statistical tests demonstrate the strong association between identity importance and overreporting, distinguishing overreporters from admitted non-exercisers but failing to distinguish them from verified exercisers. Moreover, that overreporting emerges in a self-administered form without the presence of an interviewer suggests that there is something other than social desirability bias, as it is conventionally understood, occurring. In the measurement of normative behaviors, social desirability bias is arguably not based primarily in the impression management activities of the respondent vis-à-vis an interviewer, but rather in the management of the respondent’s own impression of him- or herself. When asked a direct question about the salience of an identity during a brief, well defined reference period, the respondent with high identity importance may overreport the salience of the identity, not in order to impress an interviewer, but rather as a verbal performance consistent with the identity s/he values strongly. That this process occurs in a self-administered mode with a direct question but not in a self-administered mode using nondirective chronological measurement is strongly supportive of this conclusion.

The two measures of exercise activity also differ on the role of memory in reporting. The direct survey question in the web survey relies on retrospective reporting whereas the text condition uses in situ responding. Research by Belli et al. (1999) has suggested that some amount of overreporting of normative behaviors may be related to the effect of memory in the retrospective report. When asked about behavior that cannot be easily recalled and counted, or that which was never encoded into memory, the importance of the identity may influence the estimation procedure. The recall or estimation procedure that occurs during the process of answering a direct question enables the biasing effect of identity. In short, identity importance helps the respondent fill in the gaps in his or her memory with what s/he “usually” or “typically” does, or perhaps more to the point, what identities the respondent values in him- or herself. According to Hadaway et al. “overreporting may be generated by the respondent’s desire to report truthfully his or her identity … and the perception that the (question about identity-consistent behavior) is really about this identity rather than actual (behavior).” (adapted from Hadaway et al. 1998: 127). However, the chronological reporting procedure used in the text condition avoids this process. Future work should strive to identify ways to reduce the possibly biasing effects of memory by limiting the reference period and the focal behavior upon which the respondent is reporting.

A possible avenue for future research may be an examination of these two possible causes of overreporting (social desirability and identity) and their correlation with the two question answering processes discussed here (estimation and enumeration). It may be that identity is the primary cause of overreporting when respondents estimate the frequency of a normative behavior and that more conventional notions of social desirability are the primary cause of overreporting when respondents enumerate occurrences of a normative behavior. Unfortunately, these data cannot answer this question as there is no way to know for certain which process respondents used to generate an answer to the past week exercise question.

4.1 Limitations and Future Directions

The difference in reference periods between the two conditions was an unavoidable limitation of the study’s design. Reporting via text message for seven days would have been a much greater burden for the respondents. Conversely, a 5-day reference period for the stylized question in the web condition would have been awkward, as a week is a more “natural”Footnote 7 time frame for respondents. The main problem with this difference is that it allows respondents in Condition 1 more opportunity to overreport than those in the text condition, thereby increasing the bias in web condition compared to the text condition simply due to the study design. However, the difference in overreporting between the two conditions is so extreme that the difference in reference period is unlikely to be a major cause. Nevertheless, future work should attempt to overcome this flaw in the study design by using identical reference periods.

The characteristics of the sample may also limit the findings of the study. While the sample size is relatively small and the sample composition (undergraduates at an elite public university) is likely quite different from the general population, both of these characteristics provide the study certain strengths and open the door to future work. The size of the sample allowed intensive data collection that would not have been possible with a large sample at current funding levels. However, given adequate funding, future work could take advantage of computing resources (e.g., an automated SMS-to-HTTP service) unavailable to the researchers on this project and would allow a much larger sample at a similar level of intensity of data collection. University undergraduates provided both a convenient sample as well as one with strong physical exercise/sport identities, providing a great resource for hypothesis testing. Students in highly selective universities may, for example, place a great deal more importance on their exercise identity, leading them to both exercise and overreport at higher rates than the general population. While this is a strength of the current work, allowing a strong test of the hypotheses, extending this framework to a general, non-student population would further test this model. Moreover, a sample from the general population may yield a more balanced distribution of exercise identity importance (including more respondents with low ratings of exercise importance), allowing a more complete test of these hypotheses.

Nonresponse may also present a caveat to inferences made from this study. Respondents were presented with multiple opportunities to decide on their (continued) participation: when initially recruited to participate, when asked for a cell phone number, when asked to begin sending text updates on their activities (for text respondents), and when asked for their student identification number and permission to access their recreation facilities records. Although each additional compliance request could potentially lead to nonresponse bias, no differences emerge on variables available on the sampling frame (i.e., gender, year in school) or collected during at various stages (i.e., agreeing to participate in the text condition; granting permission to access recreation facilities records). These supplementary analyses (not shown) suggest that nonresponse is not causing differential response patterns. Moreover, findings from investigations of overreporting of other normative behaviors suggest that those sample members who engage in normative behaviors are more likely to agree to a request for survey participation (Woodberry 1998). If respondents differ from nonrespondents, they are more likely to be actual exercisers than overreporters. In short, any nonresponse bias would likely make these estimates of overreporting more conservative.

5 Conclusion

The findings of this study add credence to an identity approach to the study of overreporting of normative behavior. This approach moves the locus of the misreport from the interaction between the interviewer and the respondent to the internal conversation the respondent has with him- or herself. The motivation to present oneself in a manner consistent with important identities can lead to overreporting even on self-administered surveys. In essence, the survey question becomes an opportunity to verbally perform a highly important identity even if it is rarely performed in other situations (Burke 1980). However, chronological reporting procedures, like time diaries and the SMS/text procedure introduced here, yield more accurate reports by avoiding the priming effect of the conventional survey question.

This paper extends current work investigating the quality of measurement of normative behaviors, using physical exercise as a case for study. Focusing on the measurement of health behaviors is ideal not only because it provides a set of potentially verifiable normative behaviors that can be compared to self-reports but also because of its importance to policymakers, public health officials, and other stakeholders. By comparing respondents who accurately report their behavior with those who overreport, and theorizing about important contributing factors, we can gain insight into both methodological and substantive questions.

Methodologically, this paper not only challenges the veracity of respondents’ reports of their health behaviors, and self-reports of normative behaviors more generally, but also addresses the causes of these errors. By shifting attention to analyses in which measurement error is the dependent variable, this research moves forward from establishing the phenomenon of overreporting to investigating and elucidating the social causes of the overreport. A more complete understanding of these causes will allow survey methodologists and other quantitative social scientists to improve the measurement of this and other normative behaviors.

From a more substantive perspective, this paper’s focus on the causes of overreporting informs the research on the encouragement of positive health behaviors like physical exercise and preventative medical care. For example, the similarities between exercisers’ and overreporters’ self-concepts established here may have purchase in public outreach campaigns promoting healthy behavior. Because overreporters conceptualize themselves as exercisers, appealing to them as such may better encourage this group to act in accordance with their self-concepts.

This approach implies that measurement error is not just an annoyance to be avoided. Rather, as Schuman (1982) suggested, these errors provide us an excellent opportunity to learn about ourselves. Studying misreporting can have real-world implications, especially in the realm of health policy. When survey respondents misreport their health behaviors, like physical exercise, they are tapping into a part of themselves they see as important. Going beyond the “lie” and gaining a better understanding of the reasons behind misreporting is an invaluable finding for public health officials involved in policy creation and program planning. Knowing not only rates of overreporting but also who cares enough about their exercise identity to overreport may allow for more focused policy initiatives. While a better measure of exercise (and other normative behaviors) is certainly a goal of this research, the overreporting of normative behavior is more than just a methodological puzzle to be solved for the sake of improving measurement.

Notes

That said, there is potential in this design and future research should consider it further.

All response rates are computed as AAPOR RR 5; there were no ineligible cases nor any cases of unknown eligibility.

This question was preceded with the more general question, “In the past 7 days, how many days have you worked out or exercised?” The intent of this more general question was to achieve less biased measurement of campus recreational sports facility use by allowing the respondent to claim exercise behavior even if it did not occur at campus recreational sports facilities.

Some amount of underreporting is inevitable as respondents forget to report activities. The rate of underreporting does not differ between conditions (10 and 4 % in the text and web modes, respectively; χ2(1) = 2.06; p = 0.15), suggesting that underreporting is not attributable to the characteristics of the mode. As is not a focus of this study, it will not be discussed further here.

Comparisons will be made for both the full sample and for Condition 1. Results are not available for Condition 2 separately given the negligible number of overreporters in this condition.

Although t test comparing these means comes to the same conclusion, they are not preferred as the dependent variables are not normally distributed. Comparisons using t-tests match the results of all subsequent Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon tests.

There is, of course, nothing natural about a week. Unlike the day, month, and year, the week is perhaps the most socially-constructed unit of time (Zerubavel 1989).

References

Adams, S. A., Matthews, C. E., Ebbeling, C. B., Moore, C. G., Cunningham, J. E., Fulton, J., et al. (2005). The effect of social desirability and social approval on self-reports of physical activity. American Journal of Epidemiology, 161(4), 389–398.

Ainsworth, B. E., Jacobs, D. R., & Leon, A. S. (1993). Validity and reliability of self-reported physical activity status: the Lipid Research Clinics questionnaire. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 25(1), 92–98.

Albanes, D., Conway, J. M., Taylor, P. R., Moe, P. W., & Judd, J. (1990). Validation and comparison of eight physical activity questionnaires. Epidemiology, 1(1), 65–71.

Aquilino, W. S., & LoSciuto, L. (1990). Effects of interview mode on self-reported drug use. Public Opinion Quarterly, 54(3), 362–395.

Baranowski, T. (1988). Validity and reliability of self report measures of physical activity: An information-processing perspective. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 59(4), 314–327.

Bassett, D. R. (2000). Validity and reliability issues in objective monitoring of physical activity. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 71(2 Supplement), S30–S36.

Belli, R. F., Traugott, M. W., Young, M., & McGonagle, K. A. (1999). Reducing vote overreporting in surveys: Social desirability, memory failure, and source monitoring. Public Opinion Quarterly, 63(1), 90–108.

Bernstein, R., Chadha, A., & Montjoy, R. (2001). Overreporting voting: Why it happens and why it matters. Public Opinion Quarterly, 65(1), 22–44.

Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579–616.

Brenner, P. S. (2011). Identity importance and the overreporting of religious service attendance: Multiple imputation of religious attendance using the american time use study and the general social survey. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 50(1), 103–115.

Brenner, P. S., & DeLamater, J. D. (2013). Paradata correlates of data quality in an SMS time use study: Evidence from a validation study. Center for Demography and Ecology Working Paper No. 2013-03. University of Wisconsin-Madison. http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/cde/cdewp/2013-02.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2013.

Burke, P. J. (1980). The self: Measurement implications from a symbolic interactionist perspective. Social Psychology Quarterly, 43(1), 18–29.

Cannell, C. F., Marquis, K. H., & Laurent, A. (1977). A summary of studies of interviewing methodology. Vital and Health Statistics, Series 2, 1–68.

Cannell, C. F., Miller, P. V., & Oksenberg, L. (1981). Research on interviewing techniques. Sociological Methodology, 11, 389–437.

Chase, D. R., & Godbey, G. C. (1983). The accuracy of self-reported participation rates. Leisure Studies, 2(2), 231–235.

Chaves, M., & Stephens, L. (2003). Church attendance in the United States. In M. Dillon (Ed.), Handbook of the Sociology of Religion (pp. 85–95). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Larson, R. (1987). Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 175(9), 526–536.

Durante, R., & Ainsworth, B. E. (1996). The recall of physical activity: Using a cognitive model of the question-answering process. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 28(10), 1282–1291.

Ervin, L. H., & Stryker, S. (2001). Theorizing the relationship between self-esteem and identity. In T. J. Owens, S. Stryker, & N. Goodman (Eds.), Extending self-esteem theory and research: sociological and psychological currents (pp. 29–55). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Groves, R. M. (1989/2004). Survey errors and survey costs. New York: Wiley.

Hadaway, C. K., Marler, P. L., & Chaves, M. (1998). Overreporting church attendance in America: Evidence that demands the same verdict. American Sociological Review, 63(1), 122–130.

Jacobs, D. R., Ainsworth, B. E., Hartman, T. J., & Leon, A. S. (1993). A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activity questionnaires. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 25(1), 81–91.

Klesges, R. C., Eck, L. H., Mellon, M. W., Fulliton, W., Somes, G. W., & Hanson, C. L. (1990). The accuracy of self-reports of physical activity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 22(5), 690–697.

Kreuter, F., Presser, S., & Tourangeau, R. (2008). Social desirability bias in CATI, IVR, and web surveys: The effects of mode and question sensitivity. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(5), 847–865.

Leenders, N. Y. J. M., Sherman, W. M., Nagaraja, H. N., & Kien, C. L. (2001). Evaluation of methods to access physical activity in free-living conditions. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33(7), 1233–1240.

Matthews, C. E., & Freedson, P. S. (1995). Field trial of a three-dimensional activity monitor: Comparison with self-report. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 27(7), 1071–1078.

Matthews, C. E., Freedson, P. S., Hebert, J. R., Stanek, E. J., I. I. I., Merriam, P. A., & Ockene, I. S. (2000). Comparing physical activity assessment methods in the Seasonal Variation of Blood Cholesterol Study. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 32(5), 976–984.

Motl, R. W., McAuley, E., & DiStefano, C. (2005). Is social desirability associated with self-reported physical activity? Preventative Medicine, 40(6), 735–739.

Niemi, I. (1993). Systematic error in behavioral measurement: Comparing results from interview and time budget studies. Social Indicators Research, 30(2–3), 229–244.

Patterson, P. (2000). Reliability, validity, and methodological response to the assessment of physical activity via self-report. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 71(2 Supplement), 15–20.

Robinson, J. P. (1985). The validity and reliability of diaries versus alternative time use measures. In F. T. Juster & F. P. Stafford (Eds.), Time, goods, and well-being (pp. 33–62). Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research.

Robinson, J. P. (1999). The time-diary method: Structure and uses. In W. E. Pentland, A. S. Harvey, M. P. Lawton, & M. A. McColl (Eds.), Time use research in the social sciences (pp. 47–90). New York: Klewer/Plenum.

Rzewnicki, R., Vanden Auweele, Y., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2003). Addressing overreporting on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) telephone survey with a population sample. Public Health Nutrition, 6(3), 299–305.

Sallis, J. F., & Saelens, B. E. (2000). Assessment of physical activity by self-reports: Status, limitations, and future directions. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 71(2 Supplement), 1–14.

Schuman, H. (1982). Artifacts are in the eye of the beholder. American Sociologist, 17(1), 21–28.

Shephard, R. J. (2003). Limits to the measurement of habitual physical activity by questionnaires. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 37(3), 197–206.

Stinson, L. L. (1999). Measuring how people spend their time: A time use survey design. Monthly Labor Review, 122(1), 12–19.

Stocké, V. (2007). Response privacy and elapsed time since election day as determinants for vote overreporting. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 19(2), 237–246.

Stryker, S. (1980/2003). Symbolic interactionism: A social structural version. Caldwell, NJ: The Blackburn Press.

Stryker, S., & Burke, P. J. (2000). The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(4), 284–297.

Stryker, S., & Serpe, R. T. (1982). Commitment, identity salience, and role behavior: Theory and research example. In W. Ickes & E. S. Knowles (Eds.), Personality, roles, and social behavior (pp. 199–218). New York: Springer.

Stryker, S., & Serpe, R. T. (1994). Identity salience and psychological centrality: Equivalent, overlapping, or complimentary concepts? Social Psychology Quarterly, 57(1), 16–35.

Taylor, C. B., Coffey, T., Berra, K., Iaffaldano, R., & Casey, K. (1984). Seven-day activity and self-report compared to a direct measure of physical activity. American Journal of Epidemiology, 120(6), 818–820.

Tourangeau, R. (1984). Cognitive science and survey methods. In T. Jabine, M. Straf, J. Tanur, & R. Tourangeau (Eds.), Cognitive aspects of survey design: Building a bridge between disciplines. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. A. (2000). The psychology of survey response. New York: Cambridge University Press.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2008). 2008 Physical activity guidelines for Americans. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, ODPHP U0036.

Washburn, R., Heath, G. W., & Jackson, A. W. (2000). Reliability and validity issues concerning large-scale surveillance of physical activity. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 71(2 Supplement), 104–113.

Weisberg, H. F. (2005). The total survey error approach: A guide to the new science of survey research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Williams, E., Klesges, R. C., Hanson, C. L., & Eck, L. (1989). A prospective study of the reliability and convergent validity of three physical activity measures in a field research trial. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 42(12), 1161–1170.

Woodberry, R. D. (1998). When surveys lie and people tell the truth: How surveys oversample church attenders. American Sociological Review, 63(1), 119–121.

Zerubavel, E. (1989). The seven day circle: The history and meaning of the week. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zuzanek, J., & Smale, B. J. A. (1999). Life-cycle and across-the-week allocation of time to daily activities. In W. E. Pentland, A. S. Harvey, M. P. Lawton, & M. A. McColl (Eds.), Time use research in the social sciences (pp. 127–154). New York: Klewer/Plenum.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brenner, P.S., DeLamater, J.D. Social Desirability Bias in Self-reports of Physical Activity: Is an Exercise Identity the Culprit?. Soc Indic Res 117, 489–504 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0359-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0359-y