Abstract

Many autistic children access some form of early intervention, but little is known about the value for money of different programs. We completed a scoping review of full economic evaluations of early interventions for autistic children and/or their families. We identified nine studies and reviewed their methods and quality. Most studies involved behavioral interventions. Two were trial-based, and the others used various modelling methods. Clinical measures were often used to infer dependency levels and quality-adjusted life-years. No family-based or negative outcomes were included. Authors acknowledged uncertain treatment effects. We conclude that economic evaluations in this field are sparse, methods vary, and quality is sometimes poor. Economic research is needed alongside longer-term clinical trials, and outcome measurement in this population requires further exploration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autism is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition that occurs in as many as 1 in 54 children at the age of 8 years in the USA (Maenner et al., 2020), or up to 1 in 25 children aged 12–13 years based on an Australian study (May et al., 2020). Autistic individuals often have valuable strengths and offer diversity in skills and ways of thinking. Challenges faced by many autistic individuals living in a neurotypical world include differences in interpersonal communication and relationships, intellectual disability, attention difficulties, sensory needs, poor sleep or mental health. The autism spectrum is broad and the autistic population is extremely heterogeneous: while many individuals on the spectrum live fulfilling lives with minimal or no additional support, others have high support needs throughout their lifetime. In recent years, the neurodiversity movement has resulted in increased understanding and acceptance of autistic traits. The notion of “treating” or attempting to cure autism has long been challenged by members of the autism community (Sinclair, 1993), and more recently by researchers in the field (Leadbitter et al., 2021). Instead, neurodiversity affirming practices support individuals through acceptance of autistic traits and promotion of well-being within a strengths-based approach that also considers the individual’s physical and social environment (Leadbitter et al., 2021).

Supports and accommodations are important to enable autistic individuals to learn and participate in society, but they come at a significant cost. Buescher et al. (2014) estimated the annual cost associated with childhood autism (which includes the cost of supports and lost production) to be £3.4 billion in the UK and US$66 billion in the USA (based on 2011 prices). In Australia, the recently introduced National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) provides individual support packages to participants with wide ranging disabilities, 33.7% of whom are autistic (National Disability Insurance Agency, 2022). Reports from Buescher et al. and the NDIS both indicate that direct nonmedical, including therapeutic or capacity-building supports, are the largest contributors in these costs.

In many countries, early intervention supports are offered with the intention to improve the wellbeing of autistic children prior to starting school. These therapeutic supports have been generally viewed as goal-oriented techniques, applied in addition to the usual care received by young children to promote the development of skills and improved wellbeing (Whitehouse et al., 2020). There is a large body of research that relates to the effectiveness of such programs: a recent umbrella review included 58 systematic reviews of non-pharmacological interventions for autistic children aged 0–12 years (Trembath et al., 2022). The reviewers identified 111 different intervention practices, indicating the range of interventions that are available to families, many of which have not, to date, undergone empirical evaluation. Interventions also vary in the setting in which they are delivered, the agent who implements therapeutic techniques, and the intensity with which they are applied. Each of these factors is likely to influence cost and outcomes, presenting challenges for individuals, service providers and policymakers as they navigate the support system and prioritise programs that are most likely to be cost-effective.

In health and education systems where supports are publicly funded and resources, such as staff, funding, time and space are limited, providers and policymakers must consider the likely outcomes of intervention programs alongside the resources required to deliver them. For example, in a comparison of two programs that deliver equivalent outcomes, but with different associated costs, the one with the lower cost would be considered more cost effective. Further, programs that deliver better outcomes, but at a greater cost, would require analysis to determine if the additional costs can be justified by the additional benefits. Economic evaluation, which involves the comparison of both costs and consequences of two or more alternative programs to determine their relative cost-effectiveness, is designed to support policy makers with these judgements (Drummond et al., 2015). A brief description of economic evaluation is provided in Fig. 1 (Table 1).

Although often conducted in healthcare, economic evaluations have been infrequent in the area of autism in childhood. Lamsal and Zwicker (2017) described the challenges of economic evaluation of interventions for children with neurodevelopmental conditions (including autism), citing a lack of appropriate outcome measures, difficulty measuring family effects and service use across sectors, as well as difficulty measuring or extrapolating long-term productivity costs. The impacts of autism are experienced not only in the physical and mental health of an individual, but also among family members, and more broadly than the domains typically included in measures of health-related quality of life (HRQOL, an indicator of overall health often used by health economists). A review of paediatric cost-utility analyses revealed that conclusions relating to the cost-effectiveness of some interventions were altered by the inclusion of family spillover effects (Lavelle et al., 2019). Findings were impacted to the extent that some interventions were considered cost-effective only when spillover effects were included in the analysis. As this review highlighted, outcomes included in economic analyses in this field to date have had a narrow focus, even though the inclusion of broader outcomes, such as family spillover effects, is likely to impact results.

There appears to be increasing interest and opportunity to conduct economic evaluations of autism supports in childhood. While Weinmann et al. (2009) found inadequate economic evidence to draw conclusions about the cost-effectiveness of early interventions for autistic children at the time, several economic evaluations have been published in more recent years. Researchers in the UK (Rodgers et al., 2020) conducted a comprehensive health technology assessment that included a review of economic evaluations of early behavioral interventions for autistic children, identifying six relevant studies. Sampaio et al. (2021) identified just two economic evaluations relating to autistic children in their systematic review, suggesting that they had used more stringent search criteria. They rated both studies as good quality and provided some discussion as to the methods applied and their findings: one intervention (communication training for parents in the UK) was deemed not cost-effective when provided in addition to usual care (Byford et al., 2015), while the other intervention (aimed at children prior to diagnosis with autism in Canada) was deemed cost-effective (Penner et al., 2015).

We sought to extend these recent reviews with a broader search for any interventions aimed at improving the wellbeing of autistic children prior to school entry, or that of their families. Rather than attempt to synthesise the findings of relevant studies, we wanted to gain an understanding of the various economic methods used in the field to date, and to identify potential exemplars of good practice or gaps where further research is required.

Given the broad nature of our search and the exploratory approach intended, we conducted a scoping review. Indications for scoping reviews include aims to identify types of evidence and methods implemented in a field, and not to draw specific conclusions about a treatment’s effectiveness, for example, as might be the aim of a systematic review (Munn et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2020).

Objectives

This review was conducted to address the following research question: what economic evidence is there for early interventions aimed at young autistic children, and how have researchers evaluated their costs and benefits to date? Specifically, the aims of the review were as follows:

-

1.

To collate the best available information about the economic efficiency of interventions for autistic children during the years prior to starting school;

-

2.

To examine the methods used in conducting economic evaluations of early interventions for young autistic children;

-

3.

To understand the extent to which different types of intervention have been evaluated economically and identify where gaps exist in the evidence;

-

4.

To critique the quality of the available economic evidence; and.

-

5.

To explore how and why relative cost-effectiveness varies across settings.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

The protocol of the current review was published in 2021 (Pye et al., 2021). The review was registered on the Open Science Framework, at https://osf.io/sj7kt. It is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews PRISMA-ScR; (Tricco et al., 2018).

Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria of the review are described below in terms of participants, concepts (including interventions, phenomena or outcomes of interest) and context (including geographic location and setting), as recommended in the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Aromataris & Munn, 2020).

Participants were children diagnosed with autism or considered at increased likelihood of autism due, for example, to showing early signs of autism or having an autistic older sibling. Studies were included only if participants had not yet started school at the time supports were provided.

The concepts of the review were (a) economic evidence, in the form of full economic evaluations, (b) related to any interventions targeted to the participants above. Intervention was defined as “a modification or addition to standard care that is implemented with the intention of improving the wellbeing of an autistic child and/or their family” (Pye et al., 2021, p. 3). Such interventions could theoretically include, for example, allied health supports, alternative education strategies, medications or early identification that would enable earlier access to supports. Intended outcomes had to include the autistic child’s wellbeing and/or that of their family.

The review context was kept open, consistent with the objectives of scoping reviews and our research aims. No limitations were placed on country, publication date or analytic approach (e.g. trial- vs model-based evaluations), however full texts were required to be published in English due to resource limitations.

Information Sources

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and EconLit. Secondary searches were carried out in the National Health Service Economic Evaluations Database (NHS EED) and Health Technology Assessments (HTA), both accessed via the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) Database, and the Pediatric Economic Database Evaluation (PEDE). Grey literature was also searched using Google, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, the New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Report and the ISPOR Presentations Database. Systematic reviews of economic evaluations were checked for primary studies that may not have been identified through our own searches.

Search

Database search strategies and results are provided in Online resource 1. The primary search was developed in MEDLINE with the support of La Trobe University library research advisers with experience in systematic searches. One adviser reviewed the MEDLINE strategy using the CADTH PRESS checklist (McGowan et al., 2016), recommending several minor adjustments, before it was translated to the other databases. All databases were searched from their inception to the search date (2 Feb, 2021).

A Google search was completed on 5 Feb, 2021 using the following terms: “(“cost effectiveness”|”cost benefit”|”cost utility”|”economic evaluation”) (autism|aspergers|ASD) (child|children|preschoolers|toddlers|nursery|childcare)”.

Selection of Sources of Evidence

Two reviewers (KP and HJ) each independently screened all titles and abstracts to exclude irrelevant studies. They then independently screened full texts, resolving disagreements through consensus and by including a third reviewer (AS) as required.

Data Charting Process

Search results were imported into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, 2021), an online tool developed to support systematic reviews. Duplicates were detected and removed by Covidence, and screening, data charting and quality appraisals were completed using the Covidence 2.0 platform. The data extraction template was tested with two studies before commencing the main process.

Data Items

Data items relating to study characteristics, methods and outcomes are listed in Table 2.

Critical Appraisal

In line with our intention to understand the breadth and quality of economic evidence available, we followed recommendations for the completion of reviews of economic evaluations (Aromataris & Munn, 2020; National Institute for Health & Care Excellence, 2021; Wijnen et al., 2016). Each reviewer independently completed two well-established checklists to appraise all included studies: the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist (Husereau et al., 2013), relating to the quality of reporting, and an extended version of the Consensus of Health Economic Criteria (CHEC-ext; Evers et al., 2005; Odnoletkova et al., 2014), relating to risk of bias. The CHEC-ext includes one additional item specific to modelled evaluations. Modelled studies were further appraised using a health technology assessment checklist developed specifically for evaluating economic models (Philips et al., 2006), as recommended by Van Mastrigt et al. (2016).

Synthesis of Results

A narrative synthesis of included studies was produced, with particular focus on the types of outcomes evaluated and the methods used to identify, measure and value those outcomes. Cost-effectiveness findings were not synthesised directly due to the specificity of inputs to the time and setting where the economic evaluations were conducted, and heterogeneity in the methods used.

Results

Search Results

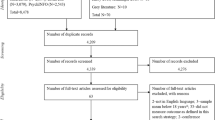

In total, 2958 database results and 89 grey literature search results were exported to Covidence. There were 808 duplicates removed by Covidence, leaving 2239 studies for title/abstract screening. The PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 2) provides detail relating to the exclusion of studies each stage. Nine studies were included in the review. The characteristics, methods and outcomes of these studies are provided in Table 3 Characteristics, methods and findings of included studies (n = 9), addressing the first three aims of the review. Results of each database search are included in Online resource 1 (Search strategy and results).

PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., 2021)

We originally sought to identify the best available information relating to the economic efficiency of early interventions for children on the autism spectrum, but to clarify, studies were not included or excluded on the basis of their quality. Instead, appraisals of their reporting and risk of bias are reported below. It is clear that economic research in this field has been limited to date, so here we focus on the available evidence, appraise its quality, and review the methods used in the field to date, rather than limit the review to even fewer studies of the highest quality. We felt this approach was consistent with the research question we sought to address, and enabled us to add more to the recent review of two good quality economic evaluations by Sampaio et al. (2021).

Characteristics of Included Studies

The nine included studies’ key characteristics and findings are summarised in Table 3 Characteristics, methods and findings of included studies (n = 9).

The included studies varied across almost all characteristics abstracted. The earliest study was published in 2006, while the remaining studies were all published in the last 10 years (since 2013), suggesting increasing interest and investment in economic research in the field (Fig. 3). All included studies were from high-income, English-speaking countries (Fig. 4).

Behaviorally based interventions were evaluated in most of the included studies, in the forms of early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) and applied behavior analysis (ABA) to reduce challenging behavior. Different forms of behavioral interventions were compared in terms of modification for delivery via telehealth, wider community access to existing programs, or earlier access enabled by screening programs and reduced wait times. Two modifications of the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) were compared with EIBI (the local status quo) in one study (Penner et al., 2015). The studies that did not involve behavioral interventions were focussed either on an eclectic autism-specific program (Synergies Economic Consulting, 2013) or the Preschool Autism Communication Trial (PACT), a developmentally-based, parent-mediated program (Byford et al., 2015). Other categories of non-pharmacological interventions (Sandbank et al., 2020) were not represented at all (Table 4).

Almost all studies included a form of usual care as the comparator, although these were specific to the context of each study and varied considerably. The Synergies (2013) study did not include any status quo intervention, but instead compared a “best practice” approach to an alternative of no intervention. Their intervention program was not described in any detail, but the choice of approach, associated costs and outcomes were all largely gathered through consultation with service providers.

A premise of several studies was that early intervention outcomes are better when intervention is delivered earlier–specifically, prior to 48 months of age. Commencement of intervention can be delayed by the diagnostic process or wait times with intervention service providers. Three of the included studies focussed on increasing the proportion of children commencing prior to 48 months of age by reducing intervention wait times (Piccininni et al., 2017), or by introducing or expanding early identification programs (Williamson et al., 2020; Yuen et al., 2018).

The perspectives taken for economic evaluations varied across healthcare (n = 1), education (n = 1), to public sector (health/welfare (n = 2), both UK), government (n = 4, all Ontario, Canada), and societal (n = 8).

Four types of economic evaluation were represented in the included studies: cost-consequence (n = 2), cost-effectiveness (n = 5), cost-utility (n = 2) and one cost–benefit analysis.

Study Methods

The majority of studies (n = 7) were based on modelled evaluations that drew on cost and outcome data available in the literature. Modelling methods varied: two studies (Penner et al., 2015; Piccininni et al., 2017) adopted a decision tree approach, representing a branching of possible outcomes based on probabilities of different treatment effects, assuming the effects were likely to be stable over time. Two other models (Motiwala et al., 2006; Synergies Economic Consulting, 2013) were not clearly described but applied a similar method, involving a series of simple equations to extrapolate costs for participant subgroups that were likely to experience different outcomes from intervention. Cohort models were used in two studies. The first used a decision tree for the intervention phase of their model, adding a 2-state (live/die) Markov model to each terminal node to extrapolate costs over the lifetime (Williamson et al., 2020). The second drew on their meta-analysis of individual participant data to determine cognitive and adaptive behavior measures at specified time points (Rodgers et al., 2020). Changes in these measures were adjusted to fit a 1-month cycle length. Finally, Yuen et al. (2018) implemented a discrete event simulation model to represent changes in resource use at specific points in time related to the proposed screening program and children’s development.

Time horizons varied greatly across studies, from short term follow-up to whole-of- lifetime. Most authors of included studies acknowledged that long term effects were uncertain. The trial-based studies implemented more immediate time horizons (with no extrapolation to longer term effects) and did not apply discounting to costs or consequences. One early identification study was based on a model to age 6 years (Yuen et al., 2018). Given the outcomes of this study were related to age of access to intervention, and not the actual intervention outcomes per se, this short time horizon also seemed reasonable. By far the largest study, the Health Technology Assessment, was modelled from age 3 to age 18.5 years (Rodgers et al., 2020). Authors cited a lack of evidence of benefits of the proposed (behavioral) interventions over (eclectic) usual care into adulthood, choosing to explore possible long-term implications through scenario analysis.

All studies that applied discounting to costs and consequences used a rate between 3 and 3.5% per annum in their base case and authors who completed sensitivity analyses used these to explore the impact of alternative discount rates. The CBA (Synergies Economic Consulting, 2013) discounted costs only, also at a rate of 3% p.a.

Measurement of Costs and Outcomes

Table 5 provides a summary of the interventions, perspectives, costs and outcomes included in each study. All societal perspective analyses considered productivity loss, usually based on a national average wage, with the exception of one study (Byford et al., 2015), where actual salaries of their study participants were used. The modelled studies accessed cost data (resource use and unit costs) either from the literature (e.g. (Buescher et al., 2014; Knapp et al., 2009) or from administrative data sources (e.g. local government, education). Rodgers et al. (2020) calculated resource use in their meta-analysis before seeking unit costs from the literature. There appears to be a lack of trial-based economic evaluations, which allow resource use to be measured, rather than estimated.

Outcomes in modelled evaluations were also necessarily drawn from the available literature. The main direct outcomes that have been reported across many effectiveness studies are cognition, and more recently, adaptive behavior and autism symptoms. These were not used as final outcomes in the included studies, but were often used to infer levels of dependency, most commonly on three tiers, which were then used to determine (a) immediate intervention outcomes, (b) educational placement, and/or (c) the need for supports such as residential accommodation in adulthood for each of the dependency groups. Rodgers et al. (2020) adopted a similar approach in assigning costs to levels of dependency, but they did so only in a scenario analysis of projected adulthood outcomes. They did not link health-related quality of life (HRQOL) outcomes to these dependency levels, citing that associations between cognition, adaptive behavior and independence, and in turn HRQOL, were not well-established. This approach demonstrates a more nuanced application of the available literature to evaluating longer term costs and outcomes.

Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were used in the two cost-utility analyses. Rodgers et al. (2020) applied an algorithm proposed by Payakachat et al. (2014) to estimate Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI-3; Feeny et al., 2002) scores based on widely available outcome measures (cognition and adaptive behavior). HUI-3 scores can be used in the calculation of QALYs, enabling cost-utility analysis. Williamson et al. (2020) also drew on the Payakachat et al. (2014) study data to assign HUI-3 scores to terminal nodes of their model: an indirect use of the same resource. The two CUAs were notably the most recent of the included studies, suggesting that methods proposed to perform CUAs in this field have been welcomed.

None of the nine studies included any negative effects, and family-based outcomes were minimally represented, consistent with outcomes traditionally included in effectiveness studies. Byford et al. (2015) observed parent–child interactions and measured features such as synchronous parent responses, and Lindgren et al. (2016) considered intervention acceptability to parents, finding that telehealth delivery of ABA was as acceptable as the original home visit model. No studies evaluated broader outcomes in the family such as parental stress, parent HRQOL or family dynamics.

Quality Appraisal

Results of the CHEERS and extended CHEC are provided in Table 6 and Table 7 respectively, and the Philips checklist data for modelled evaluations are available in Online resource 2.

The CHEERS checklist is used to appraise the quality of reporting across included studies, identifying specific studies or aspects of evaluations that were relatively well- or poorly-reported. Several CHEERS items were reported appropriately in most studies (e.g., #4 Target population and subgroups, #5 Setting & location, #6 Comparators and #22 Discussion of findings, limitations and generalisability), and no items were consistently poorly or under-reported across the included studies. Overall, we rated the reporting to be of a reasonable standard, with the well-resourced Health Technology Assessment (Rodgers et al., 2020) standing out as particularly strong, with over 80% of CHEERS items well-addressed. Studies by Penner et al. (2015), Yuen et al. (2018) and Byford et al. (2015) were also of good reporting quality (Table 7).

The CHEC list results highlighted inconsistencies in methodological quality of the included studies. Seven studies met the majority of CHEC criteria, while two studies fell well below this threshold. The Health Technology Assessment (Rodgers et al., 2020) was again rated most favourably, and met all of the CHEC criteria except providing an answerable research question. Across the included studies, there tended to be clear justification of time horizon and model inputs, but few studies reported methods of model validation.

The Philips checklist was used to review all seven modelled evaluations (Online resource 2). Rodgers et al. (2020) was again rated favourably, with a majority (70%) of Philips items adequately addressed. Just one other study was rated with a majority (52%) of items reviewed positively (Yuen et al., 2018), closely followed again by the studies by Penner et al. (2015) and Williamson et al. (2020), while the remaining studies were rated more poorly. Overall, there was inconsistency in the handling of uncertainty and heterogeneity, and model logic was infrequently tested.

Study Findings

The studies varied in their findings. Five reported that their proposed intervention was likely to yield equivalent or better outcomes at reduced cost, compared to alternatives (Lindgren et al., 2016; Motiwala et al., 2006; Penner et al., 2015; Piccininni et al., 2017; Synergies Economic Consulting, 2013). In one study (Penner et al., 2015), the result was dependent on the perspective taken: the intervention, which was both more costly and more effective than its comparator, was favourable from a societal, but not government, perspective. Two studies concluded that their proposed interventions were unlikely to be cost-effective (Byford et al., 2015; Rodgers et al., 2020). Finally, two studies were inconclusive, though both indicated that the interventions in question had potential to be cost-effective (Williamson et al., 2020; Yuen et al., 2018). With such variation in the characteristics of the included studies, it was not possible to synthesise the economic results.

In planning this review, we anticipated some variability between settings that would warrant discussion in light of the different findings relating to cost-effectiveness. In fact, the small number of included studies varied in many more ways than their settings, as described above. There were insufficient economic evaluations, across too varied interventions and methods to directly compare cost-effectiveness of specific programs across settings. It appears that variability in results may not be a question of any one parameter or method, but all.

Discussion

This scoping review included nine full economic evaluations of early supports targeted to autistic children or their families, and was particularly focussed on the methods applied in each study. A number of conclusions can be drawn from this review: these are summarised here and discussed in the paragraphs that follow. Despite a broad search strategy, the small number of full economic evaluations of any kind of interventions to support autistic children or their families indicates a paucity of evidence of their cost-effectiveness. There appears, however, to be a growing commitment to economic evaluations in this field. There have been some studies of very high quality from which fellow researchers can learn. Behavioral interventions have been most evaluated, consistent with effectiveness research, but uncertainty and tensions that exist in relation to outcomes of early interventions must be addressed. Narrow child-based clinical outcomes have been relied upon to infer downstream consequences and associated costs, despite acknowledgment in most studies that these links are not well-established. Trial-based economic evaluations have been rare to date, but are preferable to modelled studies or algorithms to extrapolate outcomes such as HRQOL or QALYs. Changing attitudes towards autism and disability have not yet been reflected in economic research in this field.

Findings and Implications

The HTA (Rodgers et al., 2020) might be considered the benchmark for current economic evidence in this field, providing lessons from its rigour and conclusions the authors made about available data. It involved ten authors who completed a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data, and a further four literature reviews to inform their economic model. The 342 page report was of a high standard. Of note was that, despite the resources they had available, these authors found they were unable to perform an evaluation (a) from a societal perspective, or (b) beyond childhood (in the base case), while each of the other studies reviewed attempted one or both of these. The HTA authors’ hesitation, even following their rigorous research, highlights the sheer amount of work involved in building a robust economic model. While the cost and outcome data in their study remain current, economists have an opportunity to draw directly on the data collated by Rodgers and colleagues to perform other economic evaluations relating to interventions for young autistic children. Future researchers might adopt their carefully considered methods or seek to address the ongoing gaps they identified.

Recently emerging methods to enable cost-utility analysis (by mapping clinical measures to health utility weights) appear to have been welcomed by researchers, although direct measurement of HRQOL within trials would be preferred. The most recent economic evaluations made use of Payakachat et al. (2014) method to map available clinical trial data onto HRQOL (HUI-3 scores; (Feeny et al., 2002)), in turn to calculate QALYs. QALYs are often used to compare the cost-effectiveness of health programs that target different outcomes or different population groups. Using QALYs, policymakers are arguably better able to prioritise budgets across disciplines, as is frequently required in healthcare. This emergence of methods to perform cost-utility analyses appears to have been welcomed by researchers. Payakachat et al. have offered the only algorithm to date that can be applied to a preschool population, but the direct measurement of HRQOL within clinical trials would ultimately provide more robust data, particularly over longer time periods. We acknowledge the complexity of measuring HRQOL in very young children with communication difficulties (Kuhlthau et al., 2010; Ungar, 2011) and consider this an important and ongoing area of research that will strengthen economic evaluations across the fields of early childhood and disability.

The impacts of autism in early childhood lie well beyond the scope of one sector of society (Lavelle et al., 2019). Several authors noted that costs and outcomes are borne by the family unit, healthcare payers, education, social care–and society as a whole (Rodgers et al., 2020; Williamson et al., 2020). This was reflected in the breadth of perspectives taken in the included analyses. Notably, in at least one study (Williamson et al., 2020), cost-effectiveness findings differed according to the perspective that was adopted. Such a difference could determine who bears the costs relating to a program, including whether or not it is publicly funded. Perspective therefore appears important in this field, and researchers should continue to adopt more than one perspective when completing economic analyses.

Behavioral interventions were by far the most researched programs in this review. This finding is unsurprising in light of recent reviews of effectiveness literature (Trembath et al., 2022). Behavioral interventions have been implemented and published for half a century, and their grounding in data-driven methods is well-suited to empirical research. Other (non-behavioral) approaches have some support in the autistic community but lag well behind behavioral programs in terms of academic evidence, and they have rarely been included in economic research to date. Unfortunately, because economic evaluations have often (necessarily) been performed using the data available, they have been limited to behavioral interventions and narrow child outcomes – and not necessarily the neurodiversity affirming programs or outcomes that might be preferred by some members of the autistic community.

Tension therefore exists between the findings of effectiveness studies (Rodgers et al., 2020; Trembath et al., 2022) and discussions in the general media, largely led by members of the autistic community. Behavioral interventions, in particular, have been associated with negative long-term outcomes (e.g. (DeVita-Raeburn & Spectrum, 2016) and even labelled as a form of conversion therapy (Kislenko, Apr 20, 2022) whereby autistic people are taught to suppress or mask behaviors thought not to conform with social expectations. There have even been calls to ban ABA therapies (Parker, 21 Mar 2015). Claims that the outcomes valued in effectiveness and economic research are not seen as valuable by the autistic community warrant further academic consideration. Leaders in behavioral research have recently sought to address some of the concerns about behavioral therapies, encouraging further discussion and calling for a review of support goals (Dawson et al., 2022; Leaf et al., 2022). Collaborative efforts might include further co-design of research with autistic people and consideration of alternative outcome measures beyond those traditionally used, such as the Autism Family Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ; Leadbitter et al., 2018), alongside the inclusion of possible negative effects.

In healthcare, researchers are increasingly conducting economic evaluations alongside clinical trials (Ramsey et al., 2015). The dangers of evaluating cost-effectiveness after establishing treatment effects are that (a) this creates a delay between understanding the treatment effects and cost-effectiveness of proposed programs, and (b) health economists are left to draw economic inferences from the clinical measures used in trials, rather than collect appropriate economic data directly from participants. As the economic research currently stands, policymakers are left with the impression that certain interventions (e.g., some behavioral programs) are cost-effective, while some community members are advocating strongly against them. A lack of measurement of HRQOL in children and families leaves the focus on offsetting downstream support costs, and not on real improvements to wellbeing. Such a focus seems to conflict with the WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disabilities and Health (World Health Organization, 2001) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations General Assembly, December 13, 2006). These statements, along with contemporary models of social support such as the Australian NDIS, have clearly promoted equal rights for people with disabilities, driven by individual aspirations, choice and community participation. However, research continues to rely on clinical measures, such as child IQ and adaptive functioning, to determine the success of a support program and to predict adult QOL. Further research with a focus on QOL, including trial-based economic evaluations and longitudinal studies, is needed.

Authors of economic evaluations have often allocated the population to levels of dependency, assigning education and social support costs differently to each level (Motiwala et al., 2006; Penner et al., 2015; Synergies Economic Consulting, 2013). While measures such as IQ might be relatively stable over time (Magiati et al., 2014) and may offer the best available predictions of future outcomes, assumed links between cognition or adaptive behavior and independence or QOL may no longer be appropriate (Lichtlé et al., 2022). For example, an individual with limited cognitive capacity or difficulty coping with changes to routine might live a happy life in a society where neurodiversity is authentically and effectively accommodated, even if the autistic individual does not change at all. This proposition warrants further investigation, including broader outcome measures and longitudinal research for incorporation into future economic analyses.

An important observation, although not set out in the aims of this review, was that none of the included studies demonstrated any attempt to measure the impacts of supports on different socio-economic groups. Inequities in access to supports have been established (Dallman et al., 2021) and disadvantaged children are particularly likely to benefit from good quality education in early childhood (Ludwig & Phillips, 2008). It seems possible that families with lower socio-economic opportunity could benefit more from formal supports than those with higher education, income and capacity to adapt. As public health and education strategies so often aim to reduce disadvantage in a population, differences in impact between socio-economic groups might impact the allocation of resources. Inequity has not been discussed or measured in economic evaluation to date in this field, and is an important area of future research.

Limitations

As with many reviews conducted by English-speaking authors, the included studies were limited to those in English. This might have excluded studies from linguistically–and likely culturally or economically–diverse countries. The included studies were all from high income, English-speaking countries, which may suggest that these are the only countries with the resources to provide early interventions, and the capacity and motivation to undertake (and publish) economic evaluations, but this speculation cannot be confirmed without including a wider range of languages in the review. English language was not used as a filter during the database search, and at full text screening no studies were excluded based on language. To be confident that non-English language studies are not excluded, future reviewers are encouraged to include other languages, such as Spanish, Chinese or French in their searches.

A second and important limitation of this study was our own lack of formal consultation with autistic individuals. While this was a review of literature, consultation or co-design might have influenced the research questions, data extracted from included studies and interpretation of findings.

Conclusions

Economic evaluations in this field have been sparse, becoming more frequent in the last 5–10 years. Inconsistent methods point to the uncertainty in intervention effects and the complex nature of autism in early childhood. Limited methods enabling cost-utility analyses are available and have been implemented only very recently. Outcomes used in cost-effectiveness analyses have largely been limited to traditional clinical measures, and have not included possible adverse effects, family-based outcomes or spillover effects, nor direct measures of child (health-related) quality of life. The use of alternative perspectives of analysis can influence cost-effectiveness findings: costs and outcomes are borne across sectors of society and this warrants careful consideration in analysis.

Recommendations are made to embark on more economic evaluations in this field, exploring alternative outcome measures, in particular measures to capture HRQOL of the child and their family. Inclusion of economic evaluations in clinical trials, and research co-design or consultation with members of the autistic community are strongly encouraged.

References

Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (2020). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI.

Buescher, A. V., Cidav, Z., Knapp, M., & Mandell, D. S. (2014). Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(8), 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210

Byford, S., Cary, M., Barrett, B., Aldred, C. R., Charman, T., Howlin, P., Hudry, K., Leadbitter, K., Le Couteur, A., McConachie, H., Pickles, A., Slonims, V., Temple, K. J., Green, J., & Consortium, P. (2015). Cost-effectiveness analysis of a communication-focused therapy for pre-school children with autism: results from a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 316. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0700-x

Dallman, A. R., Artis, J., Watson, L., & Wright, S. (2021). Systematic review of disparities and differences in the access and use of allied health services amongst children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(4), 1316–1330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04608-y

Dawson, G., Franz, L., & Brandsen, S. (2022). At a crossroads-reconsidering the goals of autism early behavioral intervention from a neurodiversity perspective. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(9), 839–840. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.2299

DeVita-Raeburn, E., & Spectrum. (2016). Is the most common therapy for autism cruel? The Atlantic. Retrieved 22.3.22, from https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/08/aba-autism-controversy/495272/

Drummond, M. F., Sculpher, M. J., Claxton, K., Stoddart, G. L., & Torrance, G. W. (2015). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford University Press.

Evers, S., Goossens, M., de Vet, H., van Tulder, M., & Ament, A. (2005). Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: Consensus on health economic criteria. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 21(2), 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266462305050324

Feeny, D., Furlong, W., Torrance, G. W., Goldsmith, C. H., Zhu, Z., Depauw, S., Denton, M., & Boyle, M. (2002). Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the health utilities index mark 3 system. Medical Care. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200202000-00006

Husereau, D., Drummond, M., Petrou, S., Carswell, C., Moher, D., Greenberg, D., Augustovski, F., Briggs, A. H., Mauskopf, J., Loder, E., & Force, C. T. (2013). Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f1049

Kislenko, C. (Apr 20, 2022). Why the 'treatment' of autism is a form of conversion therapy. Xtra*. https://xtramagazine.com/health/autism-conversion-therapy-221581

Knapp, M., Romeo, R., & Beecham, J. (2009). Economic cost of autism in the UK. Autism, 13(3), 317–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361309104246

Kuhlthau, K., Orlich, F., Hall, T. A., Sikora, D., Kovacs, E. A., Delahaye, J., & Clemons, T. E. (2010). Health-related quality of life in children with autism spectrum disorders: Results from the autism treatment network. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(6), 721–729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0921-2

Lamsal, R., & Zwicker, J. D. (2017). Economic evaluation of interventions for children with neurodevelopmental disorders: opportunities and challenges. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 15(6), 763–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-017-0343-9

Lavelle, T. A., D’Cruz, B. N., Mohit, B., Ungar, W. J., Prosser, L. A., Tsiplova, K., Vera-Llonch, M., & Lin, P.-J. (2019). Family spillover effects in pediatric cost-utility analyses. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 17(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-018-0436-0

Leadbitter, K., Aldred, C., McConachie, H., Le Couteur, A., Kapadia, D., Charman, T., Macdonald, W., Salomone, E., Emsley, R., & Green, J. (2018). The autism family experience questionnaire (AFEQ): An ecologically-valid, parent-nominated measure of family experience, quality of life and prioritised outcomes for early intervention. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1052–1062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3350-7

Leadbitter, K., Buckle, K. L., Ellis, C., & Dekker, M. (2021). Autistic self-advocacy and the neurodiversity movement: Implications for autism early intervention research and practice. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635690

Leaf, J. B., Cihon, J. H., Leaf, R., McEachin, J., Liu, N., Russell, N., Unumb, L., Shapiro, S., & Khosrowshahi, D. (2022). Concerns about ABA-based intervention: An evaluation and recommendations. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(6), 2838–2853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05137-y

Lichtlé, J., Lamore, K., Pedoux, A., Downes, N., Mottron, L., & Cappe, E. (2022). Searching for what really matters: A thematic analysis of quality of life among preschool children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52, 2098–2111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05097-3

Lindgren, S., Wacker, D., Suess, A., Schieltz, K., Pelzel, K., Kopelman, T., Lee, J., Romani, P., & Waldron, D. (2016). Telehealth and autism: Treating challenging behavior at lower cost. Pediatrics, 137(Suppl 2), S167-175. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2851O

Ludwig, J., & Phillips, D. A. (2008). Long-term effects of head start on low-income children. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136(1), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1425.005

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Baio, J., Washington, A., Patrick, M., DiRienzo, M., Christensen, D. L., Wiggins, L. D., Pettygrove, S., Andrews, J. G., Lopez, M., Hudson, A., Baroud, T., Schwenk, Y., White, E., Rosenberg, C. R., Lee, L.-C., Harrington, R. A., Huston, M., . . . Dietz, P. M. (2020). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Magiati, I., Tay, X. W., & Howlin, P. (2014). Cognitive, language, social and behavioural outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review of longitudinal follow-up studies in adulthood. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(1), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.11.002

May, T., Brignell, A., & Williams, K. (2020). Autism spectrum disorder prevalence in children aged 12–13 years from the longitudinal study of Australian children. Autism Research, 13(5), 821–827. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2286

McGowan, J., Sampson, M., Salzwedel, D. M., Cogo, E., Foerster, V., & Lefebvre, C. (2016). PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 75, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

Motiwala, S. S., Gupta, S., Lilly, M. B., Ungar, W. J., & Coyte, P. C. (2006). The cost-effectiveness of expanding intensive behavioural intervention to all autistic children in Ontario. Healthcare Policy, 1, 135–151.

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2021). Developing NICE guidelines: the manual (PMG20)

National Disability Insurance Agency. (2022). Participant numbers and plan budget data https://data.ndis.gov.au/data-downloads#budget

Odnoletkova, I., Goderis, G., Pil, L., Nobels, F., Aertgeerts, B., Annemans, L., & Ramaekers, D. (2014). Cost-effectiveness of therapeutic education to prevent the development and progression of type 2 diabetes: Systematic review. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6156.1000438

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Parker, S. (21 Mar 2015). Autism: does ABA therapy open society's doors to children, or impose conformity? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/mar/20/autism-does-aba-therapy-open-societys-doors-to-children-or-impose-conformity

Payakachat, N., Tilford, J. M., Kuhlthau, K. A., van Exel, N. J., Kovacs, E., Bellando, J., Pyne, J. M., & Brouwer, W. B. (2014). Predicting health utilities for children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research, 7(6), 649–663. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1409

Penner, M., Rayar, M., Bashir, N., Roberts, S. W., Hancock-Howard, R. L., & Coyte, P. C. (2015). Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing pre-diagnosis autism spectrum disorder (ASD)-targeted intervention with ontario’s autism intervention program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(9), 2833–2847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2447-0

Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

Philips, Z., Bojke, L., Sculpher, M., Claxton, K., & Golder, S. (2006). Good practice guidelines for decision-analytic modelling in health technology assessment: A review and consolidation of quality assessment. PharmacoEconomics, 24, 355–371.

Piccininni, C., Bisnaire, L., & Penner, M. (2017). Cost-effectiveness of wait time reduction for intensive behavioral intervention services in Ontario Canada. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2695

Prior, M., & Roberts, J. (2006). Early Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Guidelines for Best Practice.

Pye, K., Jackson, H., Iacono, T., & Shiell, A. (2021). Early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder: protocol for a scoping review of economic evaluations. Systematic Reviews 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01847-7

Ramsey, S. D., Willke, R. J., Glick, H., Reed, S. D., Augustovski, F., Jonsson, B., Briggs, A., & Sullivan, S. D. (2015). Cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials II—An ISPOR good research practices task force report. Value in Health, 18(2), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2015.02.001

Robins, D. L., Fein, D., Barton, M. L., & Green, J. A. (2001). The modifield checklist for autism in toddlers: An initial study investigating the early detection of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010738829569

Rodgers, M., Marshall, D., Simmonds, M., Le Couteur, A., Biswas, M., Wright, K., Rai, D., Palmer, S., Stewart, L., & Hodgson, R. (2020). Interventions based on early intensive applied behaviour analysis for autistic children: A systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technology Assessment, 24(35), 1–306. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta24350

Sampaio, F., Feldman, I., Lavelle, T. A., & Skokauskas, N. (2021). The cost-effectiveness of treatments for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01748-z

Sandbank, M., Bottema-Beutel, K., Crowley, S., Cassidy, M., Dunham, K., Feldman, J. I., Crank, J., Albarran, S. A., Raj, S., Mahbub, P., & Woynaroski, T. G. (2020). Project AIM: Autism intervention meta-analysis for studies of young children. Psychological Bulletin, 146(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000215

Sinclair, J. (1993). Don't mourn for us. Our Voice, 1(3). https://www.autreat.com/dont_mourn.html

Synergies Economic Consulting. (2013). Cost-benefit analysis of providing early intervention to children with autism. Retrieved 2020 Oct 01 from https://www.synergies.com.au/reports/cost-benefit-analysis-of-providing-early-intervention-to-children-with-autism/

Trembath, D., Varcin, K., Waddington, H., Sulek, R., Bent, C., Ashburner, J., Eapen, V., Goodall, E., Hudry, K., Roberts, J., Silove, N., & Whitehouse, A. (2022). Non-pharmacological interventions for autistic children: An umbrella review. Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221119368

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Ungar, W. J. (2011). Challenges in health state valuation in paediatric economic evaluation. PharmacoEconomics, 29(8), 641–652. https://doi.org/10.2165/11591570-000000000-00000

United Nations Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities, (December 13, 2006). https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

van Mastrigt, G. A., Hiligsmann, M., Arts, J. J., Broos, P. H., Kleijnen, J., Evers, S. M., & Majoie, M. H. (2016). How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for informing evidence-based healthcare decisions: A five-step approach (part 1/3). Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 16(6), 689–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2016.1246960

Veritas Health Innovation. (2021). Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org

Weinmann, S., Schwarzbach, C., Begemann, M., Roll, S., Vauth, C., Willich, S. N., & Greiner, W. (2009). Behavioural and skill-based early interventions in children with autism spectrum disorders. GMS Health Technology Assessment. https://doi.org/10.3205/hta000072

Whitehouse, A. J. O., Varcin, K., Waddington, H., Sulek, R., Bent, C., Ashburner, J., Eapen, V., Goodall, E., Hudry, K., Roberts, J., Silove, N., & Trembath, D. (2020). Interventions for children on the autism spectrum: A synthesis of research evidence. Brisbane: Autism CRC

Wijnen, B., Van Mastrigt, G., Redekop, W. K., Majoie, H., De Kinderen, R., & Evers, S. (2016). How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for informing evidence-based healthcare decisions: Data extraction, risk of bias, and transferability (part 3/3). Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 16(6), 723–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2016.1246961

Williamson, I. O., Elison, J. T., Wolff, J. J., & Runge, C. F. (2020). Cost-effectiveness of MRI-based identification of presymptomatic autism in a high-risk population. Front Psychiatry, 11, 60. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00060

World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability, and health : ICF. In. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Yuen, T., Carter, M. T., Szatmari, P., & Ungar, W. J. (2018). Cost-effectiveness of universal or high-risk screening compared to surveillance monitoring in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(9), 2968–2979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3571-4

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Hannah Buttery (Senior Officer, Research Data Outputs) and Natalie Young (Research Advisor) of La Trobe University, in their support reviewing the search strategy.

Funding

This review was completed as part of a PhD candidature supported by the Australian Government’s Research Training Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KP, AS and TI developed the concepts of this study. KP developed the search strategy with input from the other authors. KP and HJ completed screening and data extraction, with AS as third reviewer when required. KP drafted and finalised this paper with valuable contributions from the other authors, all of whom approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pye, K., Jackson, H., Iacono, T. et al. Economic Evaluation of Early Interventions for Autistic Children: A Scoping Review. J Autism Dev Disord 54, 1691–1711 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-023-05938-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-023-05938-3