Abstract

We examined data collected as a part of the Autism Treatment Network, a group of 15 autism centers across the United States and Canada. Mean Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) scores of the 286 children assessed were significantly lower than those of healthy populations (according to published norms). When compared to normative data from children with chronic conditions, children with ASD demonstrated worse HRQoL for total, psychosocial, emotional and social functioning, but did not demonstrate differing scores for physical and school functioning. HRQoL was not consistently related to ASD diagnosis or intellectual ability. However, it was consistently related to internalizing and externalizing problems as well as repetitive behaviors, social responsiveness, and adaptive behaviors. Associations among HRQoL and behavioral characteristics suggest that treatments aimed at improvements in these behaviors may improve HRQoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) is a comprehensive approach to measuring health outcomes that evaluates an individual’s psychosocial, emotional, and physical well-being (Fayers and Machin 2007). HRQoL is a subjective term that emphasizes happiness and overall well-being as they relate to disease or the treatment of said disease. The assessment of HRQoL is well-suited to conditions that have a multi-dimensional impact, such as Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). Health Related Quality of Life has received scant attention in the pediatric literature until recently, and to our knowledge, no HRQoL studies of large cohorts of children with ASD have been conducted.

Several studies have investigated HRQoL in children with both developmental and psychiatric disorders. In general, findings indicate that developmental and psychiatric disorders have adverse, yet differing, effects on children’s HRQoL. A Dutch HRQoL study of children with various psychiatric disorders found that the children with “pervasive developmental delay,” had significantly worse parent-reported psychosocial health and emotional functioning scores than children with “other psychiatric disorders.” Children with “pervasive developmental delay” also experienced worse emotional health than children with no diagnosis (Bastiaansen et al. 2004). Similarly, HRQoL studies of adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) have shown this group to have significantly poorer HRQoL than normative populations (Klassen et al. 2004; Varni and Burwinkle 2006). One study showed that the HRQoL of adolescents with ADHD worsened as the number of co-morbid psychiatric diagnoses increased (Klassen et al. 2004). In a different study, HRQoL scores were significantly worse for children with Tourette’s Syndrome and chronic tic disorder compared to an unaffected population. HRQoL was also moderately inversely correlated with symptom severity in this study (Storch et al. 2007).

While HRQoL has been associated with developmental and psychiatric diagnoses in general, HRQoL has also been associated with more specific internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Among children with psychiatric disorders and Tourette’s syndrome, children with poorer HRQoL scores had higher internalizing and externalizing behaviors measured on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach and Rescorla 2000). In general, internalizing behaviors were more highly correlated with HRQoL than were externalizing behaviors (Bastiaansen et al. 2004; Storch et al. 2007). Based on these studies, we anticipated that a similar correlation between ASD and HRQoL would be observed in the current study, with children with more severe symptoms of ASD having poorer HRQoL.

ASDs are a group of pervasive developmental disorders characterized by deficits in communication and social reciprocity and by the presence of restricted interests and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association 2000). In comparison to children with typical development, children with ASD experience significant problems related to psychological, social, and emotional health. Specifically, children with ASD face challenges with social engagement and age-appropriate play (Anderson et al. 2004; Colgan et al. 2006; Hobson and Lee 1998), friendships (Bauminger and Kasari 2000; Bauminger and Shulman 2003), and processing emotions in themselves and others (Bauminger and Kasari 2000; Bauminger and Shulman 2003; Bauminger et al. 2003; Bolte and Poustka 2003; Gross 2004; Hill et al. 2004; Teunisse and de Gelder 2001). These challenges, in combination with communication deficits and atypical behavior, often lead to poor social adjustment. Children with ASD also exhibit greater rates of depression, stress, and anxiety than typically developing children (Gurney et al. 2006; Hill et al. 2004). Lastly, children with ASD exhibit poorer physical health, more sleep issues, gastrointestinal problems, and allergies (Allik et al. 2006; Cotton and Richdale 2006; Gurney et al. 2006; Oyane and Bjorvatn 2005; Williams et al. 2004). Despite the high prevalence of these problems, little is understood about the overall HRQoL of children with ASD.

The aim of the present study was to measure HRQoL in a group of children with ASD and to relate HRQoL to ASD severity and common ASD behavioral characteristics. Past research on other child populations suggests that both ASD severity and secondary behavior issues, such as internalizing or externalizing difficulties, will influence ratings of HRQoL. We therefore hypothesized that, on traditional measures of HRQoL, children with ASD would have poorer overall HRQoL than normative healthy and chronically ill child populations. Additionally, we hypothesized that characteristics such as cognitive impairment, limited adaptive skills, and severe social impairment would be associated with poorer HRQoL. We expected that these associations would be particularly strong for aspects of HRQoL related to psychosocial health rather than physical health. Finally, we hypothesized that HRQoL would be associated with maladaptive behavioral symptoms, with children with higher levels of total behavior problems experiencing poorer HRQoL. In particular, internalizing problems (withdrawal, anxiety, somatic complaints) were expected to be more strongly associated with HRQoL than externalizing problems (aggression, oppositionality).

Methods

Participants and Procedures

All study participants were recruited between 2006 and 2008 through a hospital or clinic that is a member of the Autism Treatment Network (ATN). Originally configured as the Medical Factors study among five clinical and academic centers, the ATN has since been reconfigured into a clinical registry of 15 centers (see Table 1). Centers differed in their length of time participating in the ATN.

Participants included parents of children with a confirmed diagnosis of an ASD, who were between the ages of 2 years, 0 months and 17 years, 9 months. All children met diagnostic criteria for Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, or Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), according to the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000). Additionally, their score on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G) (Lord et al. 2000) had to meet or exceed cutoffs for categorization of autism spectrum disorder. For the 67% of children who were assessed with the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) (Lord et al. 2003) as part of the ATN Medical Factors study, all had to meet cutoffs for categorization of ASD. To participate, parents needed to speak fluent English and give informed consent. Children signed assent forms when applicable.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables were collected from a parent completed questionnaire and included children’s ethnic or racial minority status, age, and gender.

HRQoL

HRQoL was assessed through the use of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL) (Varni 1998), which is a 23-item questionnaire designed to assess children 2–18 years old. The PedsQL includes four age-appropriate versions and takes approximately 7–10 min to complete. All versions have a five-point rating scale and ask participants to think only about the previous 1-month period. The survey evaluates four distinct areas of health-related functioning: physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning and school functioning. The latter three scales are combined to determine a broad psychosocial summary score, while a physical health summary score is determined using the physical functioning scale. The items on the PedsQL surveys are converted into a 0–100 scale with high scores indicating the best HRQoL. The total PedsQL score and the accompanying summary and scale scores are computed if at least 50% of the items are completed. Some of the specific topics assessed on the PedsQL include: physical hurts and aches, energy level, feeling afraid, feeling angry, getting along with peers, paying attention in school, and keeping up with school work.

Because of the communication difficulties that are common among children with ASD, child HRQoL was assessed using the parent-report version of the PedsQL. This survey has good psychometric properties for measuring HRQoL among healthy populations as well as among children with chronic conditions; while one study reported an alpha of 0.92, another reported an alpha of 0.90 (Varni et al. 2001, 2003). The PedsQL has also been shown to distinguish between healthy populations and populations with acute and chronic health conditions (Varni et al. 2001). Lastly, recent research has shown the PedsQL to demonstrate feasibility and reliability among pediatric populations with psychiatric disorders (Bastiaansen et al. 2004a, b).

Cognitive Ability

Children’s cognitive functioning was assessed using either the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition (SB5) (Roid 2003), or the Mullen Scales of Early Learning: AGS Edition (Mullen 1997). The SB5 is an individually administered formal test of intelligence used with individuals as young as 2 years. The Mullen is an individually administered comprehensive measure of cognitive functioning for children from birth to 68 months of age. The ATN agreed upon use of the SB5 for all children enrolled in the patient registry. However, they recognized that some children with an ASD would not be able to obtain basal scores on the SB5. If there was not basal score, the Mullen was used. The SB5 was used more often than the Mullen.

Both the SB5 Nonverbal and Verbal IQ scores are expressed as standard scores with a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 15. Comparisons have been made between the SB5 and other widely accepted measures of cognitive ability, with correlations ranging from 0.78 to 0.84 for Full Scale IQ or Verbal IQ and comparable scores (Roid 2003). The internal reliability of the Mullen is good, with a median value of 0.91 across age groups. Test–retest reliability of the subscales ranged from 0.82 to 0.85 for children 1 to 24 months of age and 0.71 to 0.79 for children between 25 and 56 months of age, demonstrating good stability over time (Mullen 1997).

Adaptive Functioning

Adaptive skills were measured through the administration of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition, Survey Interview Form (Vineland-II) (Sparrow et al. 2005). The Vineland-II is a valid and reliable individually administered semi-structured caregiver interview designed to measure adaptive behavior in individuals from birth through age 90. The Vineland-II has high correlations to the previous version (Sparrow et al. 2005), which had reliability coefficients for composite scores in the mid 90s (Sparrow et al. 1984). The Vineland-II has also proven to be sensitive to changes in development over time (McGovern and Sigman 2005). The Vineland-II uses standard scores to describe an individual’s overall functioning (Adaptive Behavior Composite).

ASD-Related Symptoms

Social impairment related to ASD symptom severity was measured using the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) (Constantino 2005). The survey yields an overall severity score, with higher scores reflecting greater severity of social impairment. There is evidence for SRS score validation and construct validity (Constantino and Todd 2005). Maternal reported SRS scores correlate strongly with ADI-R algorithm scores for each subdomain of autistic symptomatology; coefficients ranged from 0.65 to 0.77 (Constantino et al. 2003).

Restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors related to ASD symptom severity were measured using the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R) (Bodfish et al. 1999). The RBS-R includes 42-items that parents rate on a four-point Likert scale. It describes the presence and severity of stereotypic, self-injurious, compulsive, ritualistic/sameness behaviors and restricted interests. A total score is generated, with higher scores indicating the presence of more intense and severe repetitive behaviors. The RBS-R has been reported to have adequate psychometric properties and acceptable reliability and validity (Bodfish et al. 1999, 2000; Gabriels et al. 2005). It has also been independently validated for use in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. The RBS-R and SRS were only completed by those individuals who were enrolled in the Medical Factors study. Thus, we have RBS data from 90 children and SRS data from 74 children.

Behavioral Adjustment

Parents reported on children’s behavior problems using the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach and Rescorla 2000). The applicability of the CBCL to children with ASD has been supported by data on scale reliability, stability, and convergent validity (Dekker et al. 2002a, b; Wallander et al. 2006). Scaled scores are expressed as T-scores that have a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. The total problems, total internalizing, and total externalizing scores were used.

Statistical Analysis

We described sample characteristics and presented means and standard errors for PedsQL scales. We compared the ASD sample data to published norms for healthy children and chronically ill children. Differences between our sample and each of the two comparison groups were computed using t-tests.

Generalized linear models were used to compare age- and gender-adjusted means by ASD diagnosis and cognitive ability. We then determined the association of cognitive ability, communication, and social functioning with PedsQL total and scale scores by using generalized linear models or regression models. Measures of statistical significance for comparisons within instruments are Bonferroni adjusted.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 286 children. The sample is predominantly male, reflecting the demographics of ASD. We have more children in the younger two age groups (36% age 2–4 years and 35% age 5–7 years) than in the older age groups (20% age 8–12 and 9% age 13 and up). The majority of the children are white (77%) and non-Hispanic (12% identified as being of Hispanic ethnicity). Just under a half (48%) of the sample has an IQ greater than 70. Approximately two-thirds of the sample (69%) was diagnosed with Autistic Disorder, 8% with Asperger’s Disorder, and 23% with PDD-NOS.

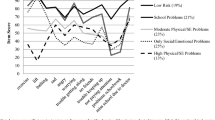

As shown in Table 2, the average total PedsQL score for the ASD sample was 65.2 ± 15.9. This score is significantly lower than the national norm for a generally healthy population (82.3 ± 15.6) and significantly lower than the norm for children with chronic conditions (73.1 ± 16.5) (p-value < 0.001 for both comparisons) (Varni et al. 2003). Significant differences in HRQoL scale scores were also found between these groups. The area with the greatest differences was social functioning, with children with ASD having lower scores than children with chronic conditions and generally healthy children. Interestingly, for measures of physical health and school functioning, the ASD sample did not differ from the chronic condition sample, although both differed from the healthy sample.

Table 3 shows the adjusted mean PedsQL scores by gender, age, ASD diagnosis and cognitive ability score category. There were no observed statistically significant differences in HRQoL by gender or specific diagnosis. However, the total scores, summary scores, and scale scores did differ by age, with older children having significantly lower scores than younger children (p-value < 0.008. The only difference in HRQoL for the two cognitive ability groups was for emotional functioning, where children in the lower scoring group had worse reported HRQoL.

A summary of the beta coefficients from multiple regression analyses are provided in Table 4. The beta coefficients are defined as the amount that the dependent variable (PedsQL total score or subscale scores) changes when the corresponding independent variable changes one unit. A negative beta coefficient represents a negative relationship between two variables. After a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons, we found a statistically significant association between the social functioning subscale of the PedsQL and the Adaptive Behavior Composite score from the Vineland-II. Specifically, the social functioning subscale score changed 0.34 units for every one unit change in the Vineland-II. There were consistent negative correlations (negative beta values) between the SRS and HRQoL on all domains, with the largest coefficients for total, psychosocial, and social aspects of HRQoL. There was also a negative relationship between HRQoL and increased reports of repetitive behaviors, with statistically significant differences for all scales except school functioning. Thus, as expected, in general, the more severe the social impairment and the restricted and repetitive behavior, the lower the HRQoL score. HRQoL was lastly negatively correlated with overall child behavior problems and internalizing and externalizing behaviors (CBCL scores), with statistically significant coefficients on all HRQoL scales. Across all HRQoL scales, the coefficients were larger for the internalizing domains of the CBCL versus the externalizing.

Discussion

Results of the present study provide support for our hypothesis that ASD-related behaviors will have an adverse effect on HRQoL. Parents of children with ASD reported child HRQoL scores that were poorer than those scores reported by parents of typically developing children, with significant differences between these two groups observed in all HRQoL domains. Similarly, scores for total HRQoL, psychosocial health, social functioning, and emotional functioning were significantly lower for children with ASD than for children with chronic health conditions. However, children with ASD did not have lower HRQoL scores for all reported domains. The physical health summary score and the school functioning score were similar between children with chronic illness and children with ASD.

Given that emotional and social impairment are defining characteristics of ASD but are not defining characteristics of conditions such as asthma and diabetes, it is not surprising that children with ASD were reported to have lower psychosocial health scores than children with chronic illness. However, what may be surprising is the fact that children with ASD scored as poorly as children with chronic illnesses in the area of physical health, as ASD has not traditionally been thought to have a substantial impact on physical health, while many other chronic illnesses do. Unique school placements for children with ASD, as well as the high intellectual aptitude of some children with ASD, may contribute to the similarity in scores on the school functioning domain of HRQoL in these groups. Comparison of HRQoL across diagnostic groups might help clinicians and families understand their experience with ASD in the context of other chronic medical conditions. A better understanding of similarities across diagnostic groups may also result in greater collaboration among advocacy groups for improving HRQoL for children with chronic medical conditions.

Within our population of children with ASD, parental reports of child HRQoL did not statically differ by diagnostic group. However, the relative infrequency of children with Asperger’s Disorder and PDD-NOS in the present sample did not lend itself to examining meaningful differences across subtypes. Further differentiation of parents’ reports of HRQoL by various groupings (Table 3) showed a significant difference between HRQoL scores in children with differing cognitive abilities, but only for emotional functioning. This difference may be explained by the developmental nature of emotional reciprocity and emotional recognition, suggesting that children with better cognitive abilities will do better with emotional functioning regardless of the severity of their ASD.

The greatest overall variation among demographic groups was related to child age. Parents of younger children consistently reported higher HRQoL scores than parents of older children. A study of children with disabilities reports similar findings related to child age (Donovan 1988). Further examination of the factors that play a role in decreasing HRQoL with age may help identify and target effective intervention strategies. Some areas for further examination include a growing awareness of “being different,” a greater ability to question the fairness of having an ASD, and a greater likelihood of having co-morbid issues such as anxiety and/or depression.

Within our population, as adaptive functioning increased, HRQoL increased as well. These results suggest that a child’s ability to interact effectively with his or her environment is directly related to his or her quality of life, while cognitive ability may not be as important. We also found that the fewer the number of autism-specific or general maladaptive behaviors, such as social impairments, repetitive behaviors, and internalizing and externalizing difficulties, the greater the HRQoL. Although relying only on associations, these findings suggest that therapies or interventions that improve children’s adaptive skills or reduce repetitive, internalizing, or externalizing behaviors, should improve HRQoL. The relative strength of the associations with psychosocial health compared to physical health seems reasonable, given that the behaviors under consideration are more socially derived. As expected, and as shown in the existing literature (Storch et al. 2007), correlations between PedsQL scores and CBCL scores are stronger for internalizing behaviors in comparison to externalizing behaviors. The stronger correlations with internalizing behaviors is not surprising for children with ASD, as withdrawal is an important component of ASD symptomatology and a significant part of the internalizing score on the CBCL.

Among the scales of the psychosocial health summary score, social functioning was consistently related to all behaviors. The emotional functioning aspects of HRQoL were also associated with many behaviors (maladaptive, social, and repetitive), but were not related to adaptive behaviors. The reason for this limited relationship may be that children with ASD can have difficulty with communication and functional living skills and still be considered by their parents to be emotionally stable. Nevertheless, if parents perceived their children as having difficulty with behavior, they were more likely to perceive them as having emotional difficulties as well. Surprisingly, repetitive behaviors were not correlated with aspects of HRQoL related to school functioning. Perhaps most children with ASD receive adequate accommodations for these particular behavioral issues, minimizing their impact.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, these results represent the collective experience of children and adolescents with ASD who are treated at autism clinics in academic medical centers. As such, they may not represent the full range of experience of children with ASD; for example, we likely excluded a disproportionate number of children with poor quality or no health insurance, children living in rural areas, and children with family situations that limit their ability to obtain specialized care in academic medical centers. It is unclear whether this would bias the relationships between characteristics of children with ASD and HRQoL. Second, our comparison to children with chronic illness and typically developing children relies on data from published norms. Third, reports of HRQoL are based on parent proxy-report, not child self-report. Though this is a validated methodology for children, the PedsQL is also commonly administered using child self-report versions. We chose only to collect parent-report surveys due to the severe cognitive and communication issues faced by a majority of our study sample; most children would not have been able to reliably self-report. In future work, we would like to measure HRQoL directly from youth with ASD. However, because there is currently no method for capturing reliable self-reports from children with severe communication and intellectual impairments, we anticipate that a sample of individuals with ASD who self-report on HRQoL would likely be biased towards less severely affected individuals. Finally, results are correlational in nature and causality cannot be inferred. Thus, while we can claim that HRQoL is related to several behavior correlates of ASD, we cannot determine whether these behavior correlates cause changes in HRQoL or whether some other, unidentified variables are contributing to both.

Despite some limitations, this study is one of the first to examine the HRQoL of children with ASD. While results suggest that parent-reported HRQoL is poorer for children with ASD than for children from a healthy normative population, they also indicate that there are some areas in which the parental view approximates that of parents of children with chronic illnesses. The current findings also have implications related to child chronological age. In future research, it would be valuable to further explore child age and related variables. For example, future studies might look at whether or not the lower scores for older children may be related to the child’s behavior and functioning, the parent’s cumulative stress, or changing expectations for child functioning over time. Similarly, in studies where findings are based on parent-reports of child HRQoL, researchers might examine whether or not the child’s quality of life is strongly linked to the parent’s quality of life. Our results lastly suggest that HRQoL is associated with a variety of behavioral challenges associated with ASD. We hope these results highlight some of the important issues contributing to quality of life in this population. Interventions targeted at improving these aspects of ASD likely have the potential to make the greatest improvements in HRQoL. Improved HRQoL suggests greater happiness and overall well-being for children with ASD and other individuals in their environment.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families.

Allik, H., Larsson, J. O., & Smedje, H. (2006). Insomnia in school-age children with asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. BMC Psychiatry, 6, 18.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders fourth edition text revision. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

Anderson, A., Moore, D. W., Godfrey, R., & Fletcher-Flinn, C. M. (2004). Social skills assessment of children with autism in free-play situations. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 8(4), 369–385.

Bastiaansen, D., Koot, H. M., Bongers, I. L., Varni, J. W., & Verhulst, F. C. (2004a). Measuring quality of life in children referred for psychiatric problems: Psychometric properties of the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales. Quality of Life Research : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment. Care and Rehabilitation, 13(2), 489–495.

Bastiaansen, D., Koot, H. M., Ferdinand, R. F., & Verhulst, F. C. (2004b). Quality of life in children with psychiatric disorders: Self-, parent, and clinician report. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(2), 221–230.

Bauminger, N., & Kasari, C. (2000). Loneliness and friendship in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development, 71(2), 447–456.

Bauminger, N., & Shulman, C. (2003). The development and maintenance of friendship in high-functioning children with autism: Maternal perceptions. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 7(1), 81–97.

Bauminger, N., Shulman, C., & Agam, G. (2003). Peer interaction and loneliness in high-functioning children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(5), 489–507.

Bodfish, J. W., Symons, F., & Lewis, M. (1999). The repetitive behavior scales: A test manual. Morgantown, NC: Western Carolina Center Research Reports.

Bodfish, J. W., Symons, F. J., Parker, D. E., & Lewis, M. H. (2000). Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism: Comparisons to mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 237–243.

Bolte, S., & Poustka, F. (2003). The recognition of facial affect in autistic and schizophrenic subjects and their first-degree relatives. Psychological Medicine, 33(5), 907–915.

Colgan, S. E., Lanter, E., McComish, C., Watson, L. R., Crais, E. R., & Baranek, G. T. (2006). Analysis of social interaction gestures in infants with autism. Child Neuropsychology: A Journal on Normal and Abnormal Development in Childhood and Adolescence, 12(4–5), 307–319.

Constantino, J. N. (2005). Social responsiveness scale. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Constantino, J. N., Davis, S. A., Todd, R. D., Schindler, M. K., Gross, M. M., Brophy, S. L., et al. (2003). Validation of a brief quantitative measure of autistic traits: comparison of the Social Responsiveness Scale with the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33, 427–433.

Constantino, J. N., & Todd, R. D. (2005). Intergenerational transmission of subthreshold autistic traits in the general population. Biological Psychiatry, 57(6), 655–660.

Cotton, S., & Richdale, A. (2006). Brief report: Parental descriptions of sleep problems in children with autism, down syndrome, and prader-willi syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27(2), 151–161.

Dekker, M. C., Koot, H. M., van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2002a). Emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 43(8), 1087–1098.

Dekker, M. C., Nunn, R., & Koot, H. M. (2002b). Psychometric properties of the revised developmental behaviour checklist scales in Dutch children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 46(Pt 1), 61–75.

Donovan, A. M. (1988). Family stress and ways of coping with adolescents who have handicaps: Maternal perceptions. American Journal of Mental Retardation: AJMR, 92(6), 502–509.

Fayers, P. M., & Machin, D. (2007). Quality of life: The assessment, analysis and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes (2nd ed. ed.). West Sussex, England: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

Gabriels, R. L., Cuccaro, M. L., Hill, D. E., Ivers, B. J., & Goldson, E. (2005). Repetitive behaviors in autism: Relationships with associated clinical features. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 26(2), 169–181.

Gross, T. F. (2004). The perception of four basic emotions in human and nonhuman faces by children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32(5), 469–480.

Gurney, J. G., McPheeters, M. L., & Davis, M. M. (2006). Parental report of health conditions and health care use among children with and without autism: National survey of children’s health. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 160(8), 825–830.

Hill, E., Berthoz, S., & Frith, U. (2004). Brief report: Cognitive processing of own emotions in individuals with autistic spectrum disorder and in their relatives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(2), 229–235.

Hobson, R. P., & Lee, A. (1998). Hello and goodbye: A study of social engagement in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28(2), 117–127.

Klassen, A. F., Miller, A., & Fine, S. (2004). Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics, 114(5), e541–e547.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Jr, Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C., et al. (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 205–223.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (2003). Autism diagnostic interview-revised. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

McGovern, C. W., & Sigman, M. (2005). Continuity and change from early childhood to adolescence in autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 46(4), 401–408.

Mullen, E. M. (1997). Mullen scales of early learning. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Oyane, N. M., & Bjorvatn, B. (2005). Sleep disturbances in adolescents and young adults with autism and asperger syndrome. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 9(1), 83–94.

Roid, G. H. (2003). Stanford binet intelligence scales (5th ed.). Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing.

Sparrow, S. S., Balla, D., & Cicchetti, D. V. (1984). Vineland adaptive behavior scales (Survey). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., & Balla, D. (2005). The vineland II adaptive behavior scales. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Storch, E. A., Merlo, L. J., Lack, C., Milsom, V. A., Geffken, G. R., Goodman, W. K., et al. (2007). Quality of life in youth with tourette’s syndrome and chronic tic disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 36(2), 217–227.

Teunisse, J. P., & de Gelder, B. (2001). Impaired categorical perception of facial expressions in high-functioning adolescents with autism. Child Neuropsychology: A Journal on Normal and Abnormal Development in Childhood and Adolescence, 7(1), 1–14.

Varni, J. W. (1998). Pediatric quality of life inventory version 4.0. Lyon, France: Mapi Research Institute.

Varni, J. W., & Burwinkle, T. M. (2006). The PedsQL as a patient-reported outcome in children and adolescents with attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder: A population-based study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4, 26.

Varni, J. W., Burwinkle, T. M., Seid, M., & Skarr, D. (2003). The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: Feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambulatory Pediatrics: The Official Journal of the Ambulatory Pediatric Association, 3(6), 329–341.

Varni, J. W., Seid, M., & Kurtin, P. S. (2001). PedsQL 4.0: Reliability and validity of the pediatric quality of life inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Medical Care, 39(8), 800–812.

Wallander, J. L., Dekker, M. C., & Koot, H. M. (2006). Risk factors for psychopathology in children with intellectual disability: A prospective longitudinal population-based study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 50(Pt 4), 259–268.

Williams, G., Sears, L. L., & Allard, A. (2004). Sleep problems in children with autism. Journal of Sleep Research, 13(3), 265–268.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Autism Speaks for funding this work and Brian Winklosky, Joyce Shu, and Kirsten Klatka for their help managing the project. We would also like to thank the Autism Treatment Network’s leadership at each of the data collection sites: Diane Treadwell-Deering, MD, Daniel Glaze, MD, Wendy Roberts, MD, Alvin Loh, MD, Patricia Manning-Courtney, MD, Cynthia Molloy, MD, MS, Agnes Whitaker, MD, Reet Sidhu, MD, Lisa Croen, PhD, Pilar Bernal, MD, Rebecca Landa, PhD, Stewart Mostofsky, MD, Margaret Bauman, MD, Martha Herbert, MD, PhD, Robert Steiner, MD, Jill James, PhD, Eldon Schulz, MD, Jill Fussell, MD, Cordelia Robinson, PhD, RN, Ann Reynolds, MD, Susan Hepburn, PhD, Judith Miles, MD, PhD, Stephen Kanne, PhD, Nancy Minshew, MD, Cynthia Johnson, PhD, Benjamin Handen, PhD, Susan Hyman, MD, Tristram Smith, PhD, Wendy Stone, PhD, Beth Malow, MD, Bryan King, MD, Raphael Bernier, PhD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuhlthau, K., Orlich, F., Hall, T.A. et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Results from the Autism Treatment Network. J Autism Dev Disord 40, 721–729 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0921-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0921-2