Abstract

The aim of this retrospective study was to retrace the trajectories and long-term outcomes of individuals with autism in France, and to explore the family experiences. Data obtained from parents enables us to follow the trajectories of 76 adults. Two-thirds of adults with severe autism had a very poor outcome. Those with moderate autism had a better outcome. In adulthood, the majority were in residential accommodation. None were living independently. The trajectories of people with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism were more positive since all of them attended school for a long time and some went to university. All of them had a good outcome but they remained dependent on aging parents who had few available supports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

At the international level, different long-term outcome studies have shown that about two-thirds of individuals with autism will remain dependent on others throughout life (Ballaban-Gil et al. 1996; Billstedt et al. 2005, 2011; Bruder et al. 2012; Eaves and Ho 2008; Gray et al. 2014; Howlin et al. 2004; Hutton et al. 2008; Gillberg 1991; Gillberg and Steffenburg 1987; Stein et al. 2001; Stoddart et al. 2013). In the 1980s, Lorna Wing (1983) suggested that there are three major groups of behaviors typical of adults diagnosed as autistic during childhood. One group remains aloof and indifferent to the company of other people. Another group is passive and friendly and accepts company as long as there are no major upsets of routines. The third group is described as active but odd. Gillberg and Steffenburg (1987) suggested that about 50 % of their population-based series of persons diagnosed in childhood as suffering from autism belonged to the first group in adult life, 25 % to the second, and 25 % to the third. They found that 35 % of the sample experienced temporary periods of aggravation of behavioral symptoms and 22 % exhibited continuing deterioration throughout puberty. In a follow-up study of 201 young adults with autism aged 18–33, in Japan, Kobayashi et al. (1992) reported that 43.2 % had shown marked improvement during adolescence, whereas 31.5 % had shown marked deterioration.

Rates for good outcome (i.e., reaching a certain level of independence and socialization) vary from one study to another, and long-term follow-up studies indicate that there is considerable heterogeneity in outcome for people with autism (Hutton et al. 2008; Seltzer et al. 2004). For individuals with high-level autism or Asperger syndrome, some have a good overall outcome, although the majority function poorly in terms of occupational and social outcome and have to rely heavily on their families (Engström et al. 2003; Howlin 2000; Stoddart et al. 2012, 2013; Szatmari et al. 1989). The different subtypes of autism, the criteria used to define outcome categories, the geographical location and provision of support and services, and the various public strategies for managing living conditions for people with disabilities are all likely to have influenced results.

In France, there are very few studies concerning the long-term outcomes of people with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). In 1990, Aussilloux and Rocques (1991) conducted a study in an area of southern France (Hérault) with 52 people with autism born between 1966 and 1973 (aged from 17 to 24 years). They found that 75 % were in residential accommodation, 8 % in psychiatric hospitals, 6 % in sheltered workshops and one was living independently. In a follow-up study in the Paris region, Thévenot et al. (2008) evidenced huge difficulties finding residential accommodation for individuals with autism, intellectual disability and challenging behaviors. Regarding outcome of young children with autism, Darrou et al. (2010) assessed 208 children first at the age of 5, followed longitudinally, and reassessed 3 years later. The results indicated two distinct outcome groups: a “high-level” group and a “low-level” group. Some profiles were characterized by a positive outcome with improved speech, developmental gains and decreased autism severity (27 %). The majority (71 %) was characterized by stability, and 2 % exhibited developmental regression. Interestingly, the amount of intervention in terms of numbers of hours was not related to outcome. Baghdadli et al. (2012) examined changes in 152 children with autism over an almost 10-year period and identified two distinct developmental trajectories. Considerable deficit remained in adolescence, but changes in adaptive skills showed two growth rates. Poor development trajectories for both social and communication outcomes were associated with the following characteristics at age 5: poor cognitive and language skills, presence of epilepsy, and severity of autism.

The presence of different subtypes of trajectories adds evidence for distinct phenotypes of autism (Anderson et al. 2009; Gabriels et al. 2001). Fountain et al. (2012) described six developmental trajectories in children with autism. These trajectories evidenced significant heterogeneity in developmental pathways, and children whose symptoms were the least severe at first diagnosis tended to improve more rapidly than those severely affected. Around 10 % of the children experienced rapid gains, moving from severely affected to high functioning. The distinction between autistic disorder and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) is important, since the meta-analysis by Rondeau et al. (2011) reported poor stability of PDD-NOS diagnosis compared to that for autistic disorder. When diagnosed before 36 months, the stability rate for PDD-NOS was only 35 % at 3-year follow-up whereas the stability rate was 76 % for the diagnosis of autistic disorder. Examination of the trajectories showed that PDD-NOS corresponded in fact to a group of heterogeneous conditions. In the DSM-5 previous diagnostic categories (autism, PDD-NOS, Asperger syndrome) are now subsumed under the single label of ASD with a huge disparity regarding the trajectory and the outcome.

A very limited number of studies have explored the trajectories and long-term outcomes of people with ASD in France. Thus, we undertook the current retrospective and longitudinal study with two aims: to retrace the trajectories and long-term outcomes of individuals diagnosed with ASD in France, and to explore family experiences.

Methods

Settings

In order to retrace the trajectories and outcomes of adults with autism, we chose to collect data provided by the parents (questionnaire and interviews) which also enabled us to assess each family’s experience.

Participants

The 76 adults aged from 18 to 54 were born between 1952 and 1990. The parents had different profiles (Table 1) with an overrepresentation of higher socioeconomic status and little ethnic diversity. The majority of the respondents were mothers.

Measures

The variables assessed included the parents’ demographic variables, the child’s age, pre- and perinatal complications, the first concerns, age at diagnosis, the terms used for announcing the diagnosis, the description of difficulties, medical problems (epilepsy, genetic disease, etc.), schooling, the different interventions, day-care and accommodation, medication, the level of satisfaction with the diagnostic process and the services, as well as outcome in adulthood (work, independent living, medication, residential placement, day-care services, medical-care home, or sheltered workshops, improvement or deterioration, and mental health problems).

Procedure

From 2002 we conducted in-depth interviews with parents of children with autism to understand their experiences more fully. We then designed a questionnaire comprising 60 questions (both closed and open-ended). This questionnaire was circulated between 2005 and 2006 by contacting parent associations, psychiatrists and facilities that care for adults with autism. The questionnaires were received from different regions in France but a majority (72 %) came from the two most densely populated areas: the Paris region (Paris and its suburbs) (40 %), and the Rhône-Alpes region in the south-east of France (32 %). We obtained 92 questionnaires completed by parents of adults with autism (61 % from the associations) enabling us to follow the trajectory of 76 adults, since 16 questionnaires were completed separately by the mother and the father for the same child, 48 questionnaires were completed by the mothers only, and 12 by the fathers only. The questionnaires completed both by mothers and fathers made it possible to check the reliability of the diagnosis, the autism severity, the trajectories, and the outcomes.

Among the parents who sent us their answers, 51 gave us their telephone number or email. We contacted them by phone or email to complete the responses. We also conducted in-depth interviews with 19 mothers and 2 fathers. The interviews were audiotaped with the respondents’ agreement and were then transcribed. This approach enabled us to understand the parents’ experiences more fully.

Analyses

We analyzed: (1) the parents’ first concerns, their experience of the diagnosis of autism, the search for services, schooling, and facilities and their levels of satisfaction; (2) the difficulties and the trajectories of their children and the outcomes in adulthood.

All the information contained in the questionnaires was captured under Modalisa software for quantitative and qualitative processing (www.modalisa.com). The open-ended questions enabled the families to expand on their views, concerns, and experiences in greater depth. The general principle underlying the coding of responses was to convert each answer into a set of categories that enables both quantitative and qualitative processing (Chamak et al. 2011; Chamak and Bonniau 2013). The severity of autism was deduced from the professional terms and the description of difficulties reported by the parents. When the diagnosis was not “Asperger syndrome” or “high-functioning autism”, the professional terms reported by the parents were: “autism”, “severe autism” or “moderate autism”, associated with description of difficulties including marked or severe deficits in verbal and nonverbal social communication skills, often intellectual disabilities, epilepsy, and distress when rituals or routines are interrupted. Two researchers involved in the study were in charge of the coding independently in order to compare the results and clear ambiguities.

For some of the individuals with autism, we summarized the main events related to diagnosis, medical history, school, services and outcome, in a synoptic representation in order to illustrate the individual trajectories and the different situations of those with severe autism and those with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Life-course trajectory of a man with severe autism. The parents were school teachers (part-time choice for caring their child). He received a risperidone treatment at the age of 23 for challenging behaviors related to the difficulty in finding an adult residential placement. Current difficulties: behavior problems and no language

Life-course trajectory of a man with severe autism. His father was a general practitioner (retired since 2004), who modify his professional activity for taking care of his son. Medical treatment: Valproic acid, Tropatepine, Meprobamate, Methotrimeprazine, Clonazepam. Current difficulties: challenging behaviors, depression, self-injury

Life-course trajectory of a woman with severe autism. Her mother had been treated with diethylstilbestrol and gave birth at 7th month of pregnancy. The child’s father was an engineer (retired) and a founding member of an association of parents with autistic children. He has been satisfied with the current residential placement. Since she was 7, she has been treated for epilepsy (sodium valproate and phenobarbital)

Life-course trajectory of a man with Asperger syndrome. He was followed-up by psychologists from preschool to primary school and by a psychiatrist when he was in middle and high school. He experienced bullying at school. After 2 months in a private high school, he has been expelled for challenging behaviors. At the age of 20, he spent 8 months in a public high school before being expelled for mental disorders. He has been living at home with his parents. No medical treatment

Life-course trajectory of a man with high-functioning autism. He received medical treatment at the age of 31 (risperidone, 9 months, and sertraline, 12 months) when he was depressed because he did not find a job. He has been living at home with his mother. Currently, he has a regular full-time job (with the “disability” status)

Variables

To evaluate overall outcomes, different indicators were taken into account: living situation, level of independence, social and communication skills, academic attainments, employment, behavioral disorders, improvement or deterioration, mental health problems, and medications (Table 2). In our study, “good outcome” indicated that the individuals had reached a certain level of independence and socialization (able to live semi-independently and to succeed at work or college) even if they remained dependent on their families for support. Those considered as having a “very poor” outcome were in residential units with services and care for dependent people with significant needs, had no language skills, and deterioration in functioning. Those considered as having a “poor” outcome required less specialized provisions compared to those considered as having a “very poor” outcome. Improvement was mentioned by the parents, as well as stabilization of epilepsy and/or behavioral problems. Some of them were employed in sheltered workshops, and had some social and communication skills. No “very good” outcome was found in our sample even for those with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism.

Ethical Considerations

Participants voluntarily completed the questionnaire, and gave their names only if they wished. In many instances, parents asked to complete the questionnaire when they heard that we were conducting a study on the experiences of parents. For the interviews, all respondents gave their informed consent. Ethical rules were enforced, particularly those concerning the respect of the participants’ privacy. Although complying with the requirements of anonymity and confidentiality, the interviews raised ethical challenges because they involved the recollection of distressing events, and the difficulty of telling a personal story to a stranger. However, when parents agreed to be interviewed, they often seemed relieved to tell their side of the story.

Results

Three Categories of Autism Severity

Our data showed clear differences in the trajectories of persons receiving a diagnosis of Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism compared with the trajectories of persons with other forms of autism, and this led us to divide the sample into three groups. Among the 76 adults, 45 were diagnosed with severe autism (aged 18–54 years), 14 with moderate autism (aged 18–35 years) and 17 with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome (aged 18–36 years) (Table 1). Among the 45 adults with severe autism, 14 had epilepsy, 3 had a genetic disease, and 34 were under medication. Among the 14 adults with moderate autism, 9 were under medication, and only one had epilepsy. Medication was less frequently administered to those diagnosed with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome (5/17 had received medication). None had epilepsy.

Trajectories: Family Experiences

The trajectories of children with autism and the impact on families begin with the first difficulties, the parents’ first concerns and the search for a diagnosis, then the search for services, schooling, and facilities.

The Parents’ First Concerns and Their Autism Diagnostic Experience

The results concerning the autism diagnostic experiences of French parents and the very early signs of autism reported by parents have already been published (Chamak et al. 2011; Chamak and Bonniau 2013; Guinchat et al. 2012).

In the sample of this study with only adults, the mean age at diagnosis varied widely: 7 ± 5 years for those with severe autism, 5 ± 4 years for those with moderate autism, and 17 ± 9 for those with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome. The mean age at diagnosis was lower for the youngest, and the mildest forms of autism were diagnosed later. Those with severe autism in our sample were the oldest, with a mean age at 28 ± 9. Those with moderate autism were the youngest, with a mean age at 21 ± 4, and those with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome, 24 ± 6.

Among the parents of adults with autism, 89 % were dissatisfied with the way the diagnosis was announced, because of long delays in obtaining it and/or a blunt announcement without care or consideration, sometimes enhancing feelings of guilt:

“I was told that my daughter was psychotic. She had epileptic seizures at 2 weeks. The autistic diagnosis was not given when she was young. I was told that she had severe behavior problems. When she was 3 we began psychotherapy but it was I who was in therapy. […] At that time, the psychiatrist told me: you love her too much. Her problem is that you love her too much. I discontinued psychotherapy.” [From a mother of an adult with severe autism born in 1974, interview 06/15/2004]

The difficulty obtaining a diagnosis at that time was linked to the reluctance on the part of the French psychiatrists to announce it because of the high degree of stigmatization associated with autism.

The Search for Services, Schooling, and Facilities

Among the 59 adults with “severe or moderate autism”, very few went to regular school when they were young. Day-care services were provided for most, but some were at home for a long time due to the lack of services (Fig. 2). All of the adults with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome attended mainstream school, and some of them went to university (or followed correspondence courses) (Figs. 4, 5).

Parents described huge difficulties for finding a place in child care or at school for their child:

“My son was not accepted. The responses I received: “Your son would disturb the group. He is too odd”. That meant: “stay home”.” [From a mother of an adult with severe autism born in 1985, email answer 02/17/2006]

Parents mentioned frequent school bullying and also child abuse:

“In middle school, all the boys were against him. He was the scapegoat. They were always attacking him, spitting on him. The teaching staff recommended we withdraw him from school and find a small private school.” [From a mother of an adult with Asperger syndrome born in 1979, interview 02/20/2006] (Fig. 4).

“Even at preschool, he was beaten up and he had a swollen lip when he came home.” [From a mother of an adult with high-functioning autism, born in 1984, interview 05/21/2003]

Even when they could speak and had academic abilities, the children with autism could be bullied and stigmatized.

Respondents described the challenges of finding available and helpful support, and complained about inadequate services and disruptions in their child’s trajectory. They mentioned inequalities between regions, while some found available services in another region after moving:

“A doctor […] explained that the best solution for our 2 year-old daughter would be a day-care hospital, and he suggested we live in Paris to find more competent doctors. We were surprised and shocked because we didn’t think that our daughter had a serious disease. In the meantime, my husband received an offer of a post in the Paris region […] When my daughter was 15, we had to find another facility, it was difficult. I was lucky enough to find a “medico-professional institute”. Then when she was 19 we had to search for another facility: we found a day-care center but with no school activity. My daughter became aggressive with the person in charge of her. She began to assault her, shouting. By chance, a friend of mine mentioned a new day-care center close to home and my daughter enjoyed it there.” [From a mother of an adult with high-functioning autism born in 1968, interview 07/30/2002]

This quote illustrates the importance of the environment and the difficulties for the parents in finding available services for their children.

A general practitioner, who was the father of a child with severe autism born in 1973, described the trajectory of his son who was in state school until 9, in private school until 16, and then received no services for 10 years. Since the age of 26, he has been going to a day-care hospital specialized in autism three times a week (Fig. 2).

Some parents however reported positive experiences. They recognized the quality of the support given and the help of professionals in some special schools, medico-educational institutes or day-care hospitals:

“In the vocational school, the professionals paid attention to my son, and there was successful coordination between the different professionals, with meetings organized by the health care team once a month (psychiatrist, psychologist). The health care team succeeded in integrating my son into a secondary school.” [From a mother of an adult with moderate autism born in 1988]

“In the “medico-educational institute”, the therapy was suited to the disability. It is an establishment that promotes a familial environment with effective cooperation between parents and professionals.” [Mother of an adult with severe autism born in 1985]

“I am satisfied with the day-care hospital where my son started at the age of 18. There is a good environment with outings and events and family meetings.” [Father of a male with severe autism born in 1985]

Most parents described the daily challenge of raising a child with autism:

“I hoped for more improvement, even though my son made some progress. Few people realize how an autistic child saps the energy of those taking care of him.” [Mother of a male with Asperger syndrome born in 1988]

In addition to dealing with the shouting, the outbursts, the sleep problems, the eating disorders, the pervasive routines etc., they often had financial problems because they had to leave their jobs or had considerable expenses for their child’s treatments and therapies. In terms of parental careers, 60 % of the mothers and 23 % of the fathers in our sample reported having given up or modified their occupations as a result of their child’s autism.

Some had suicidal thoughts:

“When she was young, when she wasn’t talking and wasn’t doing anything after an epileptic seizure, when she was like a vegetable, I felt like killing my daughter and myself because I loved her. I felt so sick.” [From a mother of an adult with severe autism born in 1974, interview 06/15/2004]

“We have already thought of killing him and killing ourselves, my husband and I.” [From a mother of an adult with Asperger syndrome born in 1979, interview 02/20/2006]

Even with children having language and cognitive abilities, parents had to cope with huge difficulties and were concerned about their children’s future.

Trajectories and Outcomes

Comparison of Trajectories/Outcomes in Relation to Autism Severity

Between 1960 and 1990 the “classic trajectory” of a child diagnosed with severe or moderate autism in France was to go to a specialized class or a day-care center from the age of 5 to 8 up to the age 12, with or without part-time school (Figs. 1, 2, 3). For the parents who did not find a place or were not satisfied with public facilities, they had to find a private school or special establishment (Fig. 2). After 12, difficulties emerged from the need to find another solution suited to adolescents, and after 18, to adults (residential accommodation, day-care services, medical-care home, or sheltered workshops). During the transitional periods, disruptions in service provision were frequent. For those with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism, school integration was much more common, but some of them went to private school or day-care centers when state schools rejected them (Figs. 4, 5).

In adulthood, 27 individuals with severe autism in our sample were in residential accommodation, 14 in day-care services, 2 were employed in sheltered workshops, one had attended a special school, and one had been in a psychiatric hospital for 6 years and then in residential accommodation. None were living independently. Parental satisfaction regarding the services reached 80 %. For those with moderate autism, 5 were in residential accommodation, 2 in day-care services, 2 were employed in sheltered workshops, and the youngest subjects (18–21) had attended a special school or vocational training (5/14). None were living independently, and some parents had to find a residential placement abroad. Parental satisfaction was 50 %.

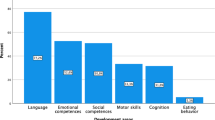

One-third of those with severe autism had a poor outcome and two-thirds had a very poor outcome (Table 3). The presence of epilepsy, intellectual disabilities, and poor communication and language skills were clearly associated with a poorer outcome. The issue of medication and side effects, such as weight gain, were often mentioned, especially for those with severe autism. In some cases, individuals with ASD engaged in severely challenging behaviors, such as aggression, self-injury, and tantrums. In case of acute behavioral crises, some were hospitalized. More than 40 % of those with moderate autism had a good outcome compared with those with the more severe manifestations of autism (Table 3).

The individuals with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome were all living with their parents, except one who was in an apartment bought by his mother, who was assisting him. One was at home all day and was depressed but after computer training he could use his skills to help people around him and he felt better (Fig. 4). One had a regular full-time job and was employed with the “disability” status (this status is an incentive for French employers to pay less social contributions in exchange for hiring workers with disabilities) (Fig. 5). One was looking for a job, two were in sheltered workshops, and the others were engaged in studies in special or private schools, in university or correspondence courses. None were in residential care. Parental satisfaction was 44 %. According to the criteria used in our study to evaluate outcome, all of them had a good outcome (Table 3). None had a very good outcome.

The typical trajectory of a child with severe symptoms of autism was very different from the trajectory of those diagnosed with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome, since the latter were attending school, had functional language, were not in residential accommodation in adulthood, and had no very poor outcomes. However some individuals with Asperger syndrome and their parents were in great difficulty:

“No services for my 26 year-old son. He has been isolated in his room for 5 years.” [Mother of an adult with Asperger syndrome, born in 1979, interview 02/20/2006] (Fig. 4).

“My son lives alone in an apartment I bought it for him. He has no friends and he is my only child. I help him. He didn’t know how to manage a budget or clean the apartment. When I am gone, the problems will remain. Nothing is solved.” [Mother of an adult with Asperger syndrome born in 1971]

Because of the high level of dependence of their children, most parents were anxious for their future:

“I wanted to find a residential accommodation because I was thinking of the time when I would be too old to care of her, and when I die…” [Mother of an adult with severe autism born in 1974, interview 06/15/2004]

Mental Health Problems and Medication in Adulthood

Although, in our sample, most individuals with autism show improvement from childhood to adulthood (language acquisition, reading and spelling), some individuals did show an increase in problems as they grew older. Anxiety and depression were the most frequent mental health problems reported by the parents, but obsessive–compulsive disorder, withdrawal, self-injury, hyperactivity, anorexia, and mood disorders were also mentioned. For those diagnosed with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome, 53 % (9/17) were described as experiencing anxiety and/or depression. Only 5 out of 17 had received medication (29 %). When they had taken medication, it was for short periods, and the reasons were often hyperactivity during childhood, anxiety, or depression, sometimes related to difficulties finding a job. Among the 45 adults with severe autism, 64 % (29/45) were reported as having anxiety and/or depression, and 73 % were under medication (antipsychotic drugs, mood stabilizers, antiepileptic drugs, antidepressants, or anxiolytics). For those with moderate autism, 43 % (6/14) were described as having anxiety, and 64 % were under medication.

Discussion

Family Experiences

The present findings illustrate the various difficulties faced by the parents when they discovered the explanation for their concerns about their child, in managing the problems, and in finding a school, day-care services, and financial support. If public support was unavailable or inadequate, the family had to compensate for this shortfall.

The first difficulty was to obtain a diagnosis. In France, children with autism born before the 1980s, had not, on average, been diagnosed until they were 7. Because of the stigmatization of the term “autism” at that time, professionals were reluctant to announce the diagnosis to the parents. After the 1990s the mean delays between first consultation and diagnosis were reduced (Chamak et al. 2011). In fact, the mean age at diagnosis varied widely. For those with severe autism, some were diagnosed before their fourth birthday but for those with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome, a diagnosis was not obtained until adolescence and even adulthood. The diagnosis of Asperger syndrome was not given by most of the French psychiatrists until the 2000s (Chamak et al. 2011; Chamak and Bonniau 2013).

As already emphasized, parenting a child with autism has a considerable impact (parental stress, lower rates of employment, lower rates of social participation, financial issues, etc.) (Davis and Carter 2008; Hastings et al. 2005) and the trajectories of their children are chaotic. When the children grow up, the problems often get worse due to the lack of services. As the parents get older they express concern about the future of their child (Hare et al. 2004; Howlin 2007). They worry about what will happen to their child when they are too old or no longer there. As underlined by Howlin et al. (2013) the reliance on aging parents as the primary caregivers for adults with autism is a particular subject of concern. In our study, for those diagnosed with severe autism, 80 % of the parents were satisfied with the services in adulthood because they found solutions for their children, but for the youngest and the other forms of autism, less than 50 % of the parents were satisfied.

Trajectories and Outcomes

Comparison of Trajectories and Outcomes of Persons with Different Levels of Autism Severity

We found that adults diagnosed with high-functioning autism had better trajectories and outcomes than those with severe or moderate autism. They attended mainstream schools. Additional skills or interests may have enabled them to be more easily integrated into society. People with severe autism did not attend mainstream schools. Many of them were still unable to speak in adulthood, and had frequent mood and behavioral disorders. Some of them had epilepsy, problems of incontinence, and remained extremely dependent. Those with moderate autism had better outcomes. The intrinsic factors identified as crucial for a good outcome included better cognitive and language abilities, whereas intellectual disability, absence of language, presence of epilepsy, and severe symptoms of autism were associated with poor or very poor outcome.

Even though adults with high-functioning autism had a better outcome, they also faced social and economic limitations, and remained dependent on aging parents. Only one person succeeded in holding down a regular full-time job. The data from 17 individuals are not sufficient to generalize to all those with high-functioning autism, but they do enable us to show that they had different trajectories from those with severe autism. The better outcome of people with Asperger syndrome has already been reported (Cederlund et al. 2008; Larsen and Mouridsen 1997). Nevertheless, these individuals often have a restricted life with no occupation and no friends (Cederlund et al. 2008; Daley et al. 2014; Engström et al. 2003; Stoddart et al. 2013; Tantam 1991), and may present mental health problems such as depression and anxiety. Rates of paid employment range from 10 to 55 %, although the majority of adults were working in sheltered workshops and participating in day programs (Cederlund et al. 2008; Farley et al. 2009; Larsen and Mouridsen 1997; Szatmari et al. 1989).

Many adolescents and young adults with autism become increasingly isolated and rates of comorbid behavioral and emotional problems remain high in adulthood (Gray et al. 2012). Although intrinsic factors such as normal or high IQ, good language abilities, and less severe symptoms of autism are significant for outcome, external factors, such as appropriate school provision, financial and social support, and the efforts made by the family, are also crucial to ensure a positive outcome. The ability to communicate effectively, less severe autism, not coming from an impoverished environment and having active parents are factors associated with more positive outcomes (Liptak et al. 2011).

The results obtained in France were not very different from those described in other countries, but many parents considered that the situation is even worse (Chamak and Bonniau 2013). Sometimes, parents decided to go to Belgium or Switzerland to find services. According to regions, services are often inadequate. The variations between urban, suburban and rural areas are complex, since in some cases families from urban or suburban regions experienced difficulties because more people needed help, rural families often encountered difficulties because of the lack of professionals and special schools or facilities, and in other cases, the quality of institutions for adults in some rural areas was higher than in urban areas. The inequalities between regions have also been described in other countries, such as the USA, the UK, and Canada (Graetz et al. 2010; Hare et al. 2004; Stoddart et al. 2013).

Mental Health Problems and Medication

In our study, anxiety and depression were the most frequent mental health problems reported: 53 % of those with high-functioning or Asperger syndrome and 64 % of those with severe autism were described as experiencing these disorders. We can consider that these results are an underestimation, since for those who have little or no speech, the risk of failing to diagnose these conditions is higher. Self-injury, hyperactivity, anorexia, and mood disorders were also mentioned. Obsessive–compulsive disorders were also reported although it appeared very difficult to distinguish between these and the ritualistic and stereotyped behaviors of autism (Szamari et al. 1989).

During childhood, individuals with autism experience high rates of anxiety (Stoddart et al. 2013). They have considerable difficulty understanding their own modes of functioning and the world around them. Often, they do not succeed in accessing regular school and when they do, they regularly experience bullying (Cappadocia et al. 2012; Schroeder et al. 2014). When the children become adolescents and adults, more problems emerge, including behavioral crises and side effects of medication. The proportion of individuals taking medications increase over time, as does the number of medications taken (Esbensen et al. 2009; Stoddart et al. 2013). Older age, along with more restrictive housing conditions and more severe autism are all associated with increased medication use (Engstrom et al. 2003; Lake et al. 2012). The challenge for the parents is to find an appropriate solution for their dependent child (medical-care home, residential accommodation or sheltered workshop). Although it is clear that some individuals with ASD do show an increase in problems as they grow older, the improvement over time of the majority is also important to note.

How Far can Early Interventions Affect Outcome in Adult Life?

Intensive behavioral methods were not in general used for individuals with autism born between 1952 and 1990. These individuals, as children with autism, went in mainstream schools, special schools, day-care hospital, or medico-educational institute. It is essential to investigate the long term outcomes of interventions, but the difficulties in attributing the positive or negative results to a given intervention, school inclusion, parental initiatives or spontaneous recovery are considerable, and the heterogeneity of the autistic profiles increases the difficulties (Camarata 2014; Vivanti et al. 2014). The example of dependent adults with autism who received intensive behavioral interventions early in childhood is reported by parents and psychiatrists, for example in Montreal (unpublished data). In contrast, some individuals who did not receive these interventions have evolved positively (among the best known: Temple Grandin, Donna Williams, Gunilla Gerland, Jim Sinclair). Personal accounts have increased in number since the 1990s when the diagnostic criteria of autism were broadened, and more people participated in associations of persons with autism, redefining autism as a way of being, and adopting the concept of neurodiversity (Chamak 2008, 2010; Ortega 2009). Commitment to associative movements and exchanges with others via internet may favor better quality of life.

The public strategies for managing living conditions for people with disabilities are of prime importance, as are assistance and services for the parents. The shortage of solutions for adults with autism and the increased burden for parents are subjects of concern. Lack of available support for caregivers and for individuals with autism leads to an aggravation of the expression of the syndrome, and numerous psychosocial problems (Graetz 2010; Stoddart et al. 2013).

Limitations of the Study

First, the findings are dependent upon the sample of respondents that completed the survey. The questionnaires were completed by parents with different profiles but with an overrepresentation of higher socioeconomic status and little ethnic diversity. Second, the data were derived from parental reports, and quite possibly parents who experienced difficulties were more likely to complete the questionnaire. This bias could explain the need for support that is prominent for most, if not all, individuals. Third, retrospective reports are prone to errors and it was not possible to check the accuracy of the diagnoses reported by the parents. Nevertheless, the questionnaires completed by mothers and fathers separately enabled the reliability of the diagnosis and the autism severity to be checked.

References

Anderson, D. K., Oti, R. S., Lord, C., & Welch, K. (2009). Patterns of growth in adaptive social abilities among children with ASD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(7), 1019–1034.

Aussilloux, C., & Rocques, F. (1991). Devenir des enfants psychotiques à l’âge adulte. Revue de neuropsychiatrie de l’Ouest, 106, 27–33.

Chamak, B. (2008). Autism and social movements: French parents’ associations and international autistic individuals’ organizations. Sociology of Health and Illness, 30(1), 76–96.

Chamak, B. (2010). Autism, disability and social movements. Alter, European Journal of Disability Research, 4(2), 103–115.

Chamak, B., Bonniau, B., Oudaya, L., & Ehrenberg, A. (2011). The autism diagnostic experiences of French parents. Autism, 15(1), 83–97.

Chamak, B., & Bonniau, B. (2013). Changes in the diagnosis of autism: How parents and professionals act and react in France. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 37(3), 405–426.

Baghdadli, A., Assouline, B., Sonié, S., Pernon, E., Darrou, C., Michelon, C., et al. (2012). Developmental trajectories of adaptive behaviors from early childhood to adolescence in a cohort of 152 children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(7), 1314–1325.

Ballaban-Gil, K., Rapin, I., Tuchman, R., & Shinnar, S. (1996). Longitudinal examination of the behavioral, language, and social changes in a population of adolescents and young adults with autistic disorder. Pediatric Neurology, 15(3), 217–223.

Billstedt, E., Gillberg, C., & Gillberg, C. (2005). Autism after adolescence: Population-based 13–22-year Follow-up study of 120 individuals with autism diagnosed in childhood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(3), 351–359.

Billstedt, E., Gillberg, C., & Gillberg, I. (2011). Aspects of quality of life in adults diagnosed with autism in childhood. Autism, 15(1), 7–20.

Bruder, M. B., Kerins, G., Mazzarella, C., Sims, J., & Stein, N. (2012). Brief report: The medical care of adults with autism spectrum disorders: Identifying the needs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(11), 2498–2504.

Camarata, S. (2014). Early identification and early intervention in autism spectrum disorders: Accurate and effective? International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(1), 1–10.

Cappadocia, C., Weiss, J. A., & Depler, D. (2012). Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(2), 266–277.

Cederlund, M., Hagberg, B., Billstedt, E., Gillberg, I. C., & Gillberg, C. (2008). Asperger syndrome and autism: A comparative longitudinal follow-up study more than 5 years after original diagnosis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(1), 72–85.

Daley, T. C., Weisner, T., & Singhal, N. (2014). Adults with autism in India: A mixed-method approach to make meaning of daily routines. Social Science and Medicine, 116, 142–149.

Darrou, C., Pry, R., Pernon, E., Michelon, C., Aussilloux, C., & Baghdadli, A. (2010). Outcome of young children with autism. Does the amount of intervention influence developmental trajectories? Autism, 14(6), 663–677.

Davis, N. O., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(7), 1278–1291.

Eaves, L. C., & Ho, H. H. (2008). Young adult outcome of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(4), 739–747.

Engström, I., Ekström, L., & Emilsson, B. (2003). Psychosocial functioning in a group of Swedish adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Autism, 7(1), 99–110.

Esbensen, A. J., Greenberg, J. S., Seltzer, M. M., & Aman, M. G. (2009). A longitudinal investigation of psychotropic and non-psychotropic medication use among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(9), 1339–1349.

Farley, M., McMahon, W., Fombonne, E., Jenson, W., Miller, J., Gardner, M., et al. (2009). Twenty-year outcome for individuals with autism and average or near-average cognitive abilities. Autism Research, 2, 109–118.

Fountain, C., Winter, A., & Bearman, P. (2012). Six developmental trajectories characterize children with autism. Pediatrics, 129(5), 1–9.

Gabriels, R. L., Hill, D. E., Pierce, R. A., Rogers, S. J., & Wehner, B. (2001). Predictors of treatment outcome in young children with autism: A retrospective study. Autism, 5, 407–429.

Gillberg, C. (1991). Outcome in autism and autistic-like conditions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(3), 375–382.

Gillberg, C., & Steffenburg, S. (1987). Outcome and prognostic factors in infantile autism and similar conditions: A population-based study of 46 cases followed through puberty. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 17, 273–287.

Graetz, J. E. (2010). Autism grows up: Opportunities for adults with autism. Disability & Society, 25(1), 33–47.

Gray, K., Keating, C., Taffe, J., Brereton, A., Einfeld, S., Reardon, T., & Tonge, B. (2014). Adult outcomes in autism: Community inclusion and living skills. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3006–3015.

Gray, K., Keating, C., Taffe, J., Brereton, A., Einfeld, S., & Tonge, B. (2012). Trajectory of behaviour and emotional problems in autism. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 117(2), 121–133.

Guinchat, V., Chamak, B., Bonniau, B., Cohen, D., & Danion, A. (2012). Very early signs of autism reported by parents include many concerns not specific to autism criteria. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 589–601.

Hare, D. J., Pratt, C., Burton, M., Bromley, J., & Emerson, E. (2004). The health and social care needs of family carers supporting adults with autistic spectrum disorders. Autism, 8(4), 425–444.

Hastings, R. P., Kovshoff, H., Ward, N. J., Degli Espinosa, F., Brown, T., & Remington, B. (2005). Systems analysis of stress and positive perceptions in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(5), 635–644.

Howlin, P. (2000). Outcome in adult life for more able individuals with autism or Asperger syndrome. Autism, 4(1), 63–83.

Howlin, P. (2007). The Outcome in adult life for people with ASD. In F. Volkmar (Ed.), Autism and pervasive developmental disorders (pp. 269–306). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Howlin, P., Goode, S., Hutton, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 212–229.

Howlin, P., Moss, P., Savage, S., & Rutter, M. (2013). Social outcomes in mid to later adulthood among individuals diagnosed with autism and average nonverbal IQ as children. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(6), 572–581.

Hutton, J., Goode, S., Murphy, M., Le Couteur, A., & Rutter, M. (2008). New-onset psychiatric disorders in individuals with autism. Autism, 12(4), 373–390.

Kobayashi, R., Murata, T., & Yoshinaga, K. (1992). A follow-up study of 201 children with autism in Kyushu and Yamaguchi areas, Japan. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 22(3), 395–411.

Lake, J. K., Balogh, R., & Lunsky, Y. (2012). Polypharmacy profiles and predictors among adults with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(3), 1142–1149.

Larsen, F. W., & Mouridsen, S. E. (1997). The outcome in children with childhood autism and Asperger syndrome originally diagnosed as psychotic. A 30-year follow-up study of subjects hospitalized as children. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 6(4), 181–190.

Liptak, G. S., Kennedy, J. A., & Dosa, N. P. (2011). Social participation in a nationally representative sample of older youth and young adults with autism. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 32(4), 277–283.

Ortega, F. (2009). The cerebral subject and the challenge of neurodiversity. Biosocieties, 4(4), 425–445.

Rondeau, E., Klein, L., Masse, A., Bodeau, N., Cohen, D., & Guilé, J. M. (2011). Is pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified less stable than autistic disorder? A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(9), 1267–1276.

Schroeder, J. H., Cappadocia, M. C., Bebko, J. M., Pepler, D. J., & Weiss, J. A. (2014). Shedding light on a pervasive problem: A review of research on bullying experiences among children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1520–1534.

Seltzer, M. M., Shattuck, P., Abbeduto, L., & Greenberg, J. S. (2004). Trajectory of development in adolescents and adults with autism. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 10(4), 234–247.

Stein, D., Ring, A., Shulman, C., Meir, D., Holan, A., Weizman, A., et al. (2001). Brief report: Children with autism as they grow up—description of adult inpatients with severe autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(3), 355–360.

Stoddart, K. P., Burke, L., & King, R. (2012). Asperger syndrome in adulthood: A comprehensive guide for clinicians. New York: Norton Publishers.

Stoddart, K. P., Burke, L., Muskat, B., Manett, J., Duhaime, S., Accardi, C., et al. (2013). Diversity in Ontario’s youth and adults with autism spectrum disorders: Complex needs in unprepared systems. Toronto, ON: The Redpath Centre.

Szatmari, P., Bartolucci, G., Brenner, R., Bond, S., & Rich, S. (1989). A follow-up study of high-functioning autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 19(2), 213–225.

Tantam, D. (1991). Asperger syndrome in adulthood. In U. Frith (Ed.), Autism and Asperger syndrome (pp. 147–183). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thévenot, J. P., Philippe, A., & Casadebaig, F. (2008). Accès aux institutions des enfants et adolescents avec autisme ou troubles apparentés: une étude de cohorte en Ile-de-France de 2002 à 2007. Montrouge: John Libbey Eurotext.

Vivanti, G., Prior, M., Williams, K., & Dissanayake, C. (2014). Predictors of outcomes in autism early intervention: Why don’t we know more? Frontiers in Pediatrics, 2, 1–10.

Wing, L. (1983). Social and interpersonal needs. In E. Schopler & G. Mesibov (Eds.), Autism in adolescents and adults (pp. 337–353). New York: Plenum Press.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by INSERM (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale), and the Fondation de France. We wish to thank Pr. A. Danion and Dr. V. Pascal from Louis Pasteur University (IRIST-Strasbourg) for their participation in the design and the distribution of the questionnaire, as well as Pr. David Cohen from the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital. We are grateful to the parents’ associations and the professionals who distributed the questionnaire, and the parents who took the time to fill it in and answer our questions. We would also like to thank also Christine Calderon for her transcriptions of interviews, as well as Angela Swaine Verdier and Ken Day for rereading the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Brigitte Chamak led the conceptualization and design of the study, conducted the in-depth interviews, collected and analyzed the data, drafted the initial manuscript, revised the manuscript. Béatrice Bonniau contributed to the design of the study, collected and analyzed the data, and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chamak, B., Bonniau, B. Trajectories, Long-Term Outcomes and Family Experiences of 76 Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 46, 1084–1095 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2656-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2656-6