Abstract

Few studies have investigated bullying experiences among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders (ASD); however, preliminary research suggests that children with ASD are at greater risk for being bullied than typically developing peers. The aim of the current study was to build an understanding of bullying experiences among children with ASD based on parent reports by examining rates of various forms of bullying, exploring the association between victimization and mental health problems, and investigating individual and contextual variables as correlates of victimization. Victimization was related to child age, internalizing and externalizing mental health problems, communication difficulties, and number of friends at school, as well as parent mental health problems. Bullying prevention and intervention strategies are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bullying is a relationship problem involving repeated hostile actions that take place within a relationship characterized by a power differential (Olweus 1993; Pepler and Craig 2000). Among children, power can be attained through advantages in social status or popularity, physical size and/or strength, age, intellectual ability, and/or membership in a socially defined dominant group (Pepler et al. 2008). In the general population, bullying experiences are common among Canadian children, with 35% reporting victimization (Molcho et al. 2009). With respect to forms of bullying employed by school-aged children, verbal (e.g., name calling) and social (e.g., rumour spreading or leaving someone out on purpose) are most common (Scheithauer et al. 2006; Woods and White 2005).

Bullying experiences among children and youth are associated with many negative outcomes. Research in the general population indicates that children who are bullied are more likely to exhibit psychosomatic symptoms, poor social and emotional adjustment, low ratings of school commitment, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and clinically significant social problems, as well as delinquent behaviors such as substance abuse, carrying weapons at school, and physical fighting (Delfabbro et al. 2006; Forero et al. 1999; Grills and Ollendick 2002; Haynie et al. 2001; Kaltiala-heino et al. 2000; Kumpulainen et al. 1998; Mitchell et al. 2007; Nansel et al. 2001, 2003; Ybarra 2004; Ybarra and Mitchell 2004, 2007; Ybarra et al. 2006). Longitudinal bullying research has indicated a bidirectional relationship between bullying and mental health problems. One study indicated that children who were consistently bullied by peers had an increased risk of developing new mental health related symptoms within the year while children who reported higher levels of mental health problems than peers were more likely to be bullied within the year (Fekkes et al. 2006). Researchers have not explored the relationship between bullying experiences and mental health problems among children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). In this exploratory study, we sought to identify the predictors of bullying experiences, as well as the impact of these experiences on mental health in school age individuals with ASD.

Few studies have investigated bullying experiences among children diagnosed with ASD. Preliminary research suggests that children with ASD are at greater risk for being bullied than typically developing peers. One study indicated that bullying experiences were more than 4 times more likely among 411children with ASD than for a national sample of youth in the United States (55% vs. 13%, respectively; Little 2002). A subsequent study of 34 parents of children 5–21 years of age with ASD indicated that roughly 65% of the children had been victimized by peers (Carter 2009). Wainscot et al. (2008) found similar rates among 57 youth diagnosed with high functioning ASD. These researchers also found that youth with ASD engaged in fewer social interactions at school and reported having fewer friends than their peers; however, they did not explore empirical links between a lack of friends or poor social skills and bullying (Wainscot et al. 2008). To date, neither the forms of bullying experienced by youth with ASD (i.e., verbal, physical, or social), nor the frequency of these experiences have been explored.

Children with ASD may be at greater risk for peer victimization than typically developing peers for many reasons related to their socio-communicative and behavioral difficulties, along with the impact of these difficulties on peer interactions (and vice versa). Communication impairments in youth with ASD may place them at increased risk for victimization, as assertiveness and healthy communication in the face of peer victimization are suggested as important protective factors (Arora 1991; Sharp and Cowie 1994). Children with ASD may also become targets for aggressive peers due to atypical interests and/or behaviors compared to peers, as well as intense emotional and/or behavioral reactions to victimization, which likely encourage the child who is bullying (Gray 2004).

Children with ASD struggle with initiating and sustaining peer interactions, due to their difficulties with respect to communication and social skills. These children have difficulties with forming and maintaining friendships with peers, which likely place them at risk for peer victimization since research indicates that poor peer relationships are associated with being bullied (Delfabbro et al. 2006; Forero et al. 1999; Nansel et al. 2001; Williams and Guerra 2007). Peers play an important role in the development, maintenance, and dissolution of bullying episodes; they provide an audience for youth who bully and represent potential allies for victimized youth (O’Connell et al. 1999). Due to their social difficulties, children with ASD likely do not benefit from the protective factor of supportive peers. In fact, they may be at greater risk for victimization due to their marginalization among peers.

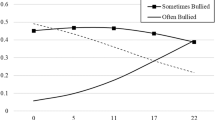

A developmental-contextual perspective was employed in the current study to conceptualize variables that would be associated with victimization among children with ASD (Ford and Lerner 1992). From a developmental perspective, children’s individual characteristics such as age, gender, and severity of ASD symptoms may shape victimization experiences. Researchers have found that boys generally tend to be victimized more than girls and that victimization peaks in the middle school years and during the transition to high school (roughly ages 12–15), decreasing thereafter (Forero et al. 1999; Nansel et al. 2001; Pepler et al. 2006a; Williams and Guerra 2007). Although the severity of ASD symptoms is negatively correlated with successful social inclusion and peer relationships, even children and adolescents with high functioning ASD continue to struggle with social competence as they age (Bauminger and Kasari 2000; Orsmond et al. 2004), which continues to place them at risk for bullying experiences.

From a contextual perspective, children’s relationships within proximal social contexts such as the family and peer group may contribute to victimization experiences. Parents represent children’s primary socialization agents and play a critical role in their children’s social development and understanding. The bullying literature on typically developing youth indicates that peer victimization experiences are related to poor parent–child relationships (Spriggs et al. 2007; Ybarra and Mitchell 2004). Because peers have such a critical socialization role during childhood and adolescence (Brown et al. 1986), peer relationships are likely implicated in the consideration of risks and protective processes related to victimization. Researchers have found that poor peer relationships place youth at risk for victimization, while having close friends protects against victimization within the general population (Delfabbro et al. 2006; Forero et al. 1999; Nansel et al. 2001; Pellegrini and Bartini 2000; Pellegrini et al. 1999; Williams and Guerra 2007). As with typically developing children, the presence of friends is also suggested to reduce risk of victimization among children with ASD (Gray 2004).

The aim of the current study was to build an understanding of bullying experiences among children with ASD. Our first goal was to examine parents’ reports of rates of various forms of bullying (physical, verbal, social, and cyber) experienced by their children with ASD. We hypothesized that social and verbal forms of bullying would be reported more often than physical forms, consistent with research on victimization experienced by typically developing children. The second goal was to explore the association between victimization and mental health problems. We hypothesized that victimization would be associated with parents’ ratings of both internalizing and externalizing mental health problems exhibited by their children with ASD. The final goal was to explore individual variables (specifically child age, social skills deficits, communication difficulties, internalizing mental health problems, and externalizing mental health problems) and contextual variables (specifically parent mental health and number of friends child has at school) as correlates of victimization. We hypothesized that each of these variables would be independently correlated with victimization to some degree.

Method

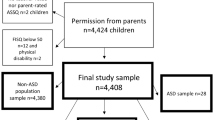

Participants

Participants included 192 parents of children diagnosed with ASD aged 5–21 years old (85% boys and 15% girls; mean age = 11.71, SD = 3.55), who were enrolled in elementary, middle, or high school (i.e., grades 1–12). Children’s diagnoses included Asperger syndrome (54%), high functioning autism (14%), PDD-NOS (13%), and autism (19%). Roughly 80% of these children were placed in full-inclusion classrooms and 20% were placed in special education classrooms or programs. The survey was completed through parent report (88% mothers, 9% fathers, and 3% other caregivers such as grandparents). Seventy-five percent of parents were married at the time of survey completion. Highest education levels among parents were as follows: 20% obtained a post graduate degree, 26% graduated university, 33% graduated college, 19% graduated high school, and 2% completed some high school. The distribution of reported household income levels among participants were: 10% at $20,000 or less, 11% at $21,000–$40,000, 16% at $41,000–$60,000, 14% at $61,000–$80,000, 18% at $81,000–$99,000, and 31% at $100,000 or higher. Most of the participants were from Canada (92%), with many living in Ontario (60%), British Columbia (12%), Alberta (10%), Newfoundland/Labrador (7%), and New Brunswick (1.5%), as well as Quebec, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba (each 0.5%). The remaining 8% of participants were from the United States. Participants identified themselves with respect to ethnicity as follows: 93% as European, 5.5% as Asian, 4% as Native Canadian, 2.5% as Latin/South American, 1.5% as Middle Eastern, 0.5% as African/West-Indian, and 0.5% as South Asian (percentages do not add up to 100% because some participants identified with multiple ethnicities).

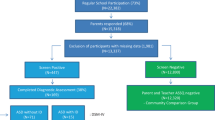

Procedure

Parents were recruited through convenience and snowball sampling. We posted an invitation to participate in an online survey on several Canadian Asperger and Autism advocacy websites (e.g., Autism Ontario, Asperger Society of Ontario). The invitation was also circulated via email lists and newsletters associated with these organizations. Parents were directed to access the survey by clicking on a link in the body of the invitation. Parents were also able to forward the invitation to other parents of children with ASD. A mailing address was provided, to accommodate requests for hard copies of the questionnaire.

Informed consent was obtained online from all participants before they were able to access the survey. The consent form emphasized that participation was voluntary and confidential, and that withdrawal was possible at any time. The survey took approximately 30 min to complete. As a token of appreciation for participation, parents were given the choice to enter into a draw for $300 by providing an email address for correspondence. This research was approved by the York University Research Ethics Board.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire Parents were asked to indicate their gender and household income, as well as their child’s age, gender, grade, number of friends, and specific ASD diagnosis.

Kessler 6-Item Psychological Distress Scale (K6; Kessler et al. 2003) is a six-item screening tool for non-specific psychological distress among adults that asks about the frequency of symptoms (e.g. nervousness, hopelessness, etc.) on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from none of the time (0) to all of the time (4). The K6 is a core measure in the annual US National Health Interview Survey, the US National Household Survey of Drug Abuse, and the Canadian National Health Interview Survey. The K6 has high internal consistency (alpha coefficient = .89) and construct validity when compared to other mental health screening tools (Furukawa et al. 2003; Kessler et al. 2002), and shows good agreement with widely used epidemiological diagnostic interviews (Kessler and Ustun 2004; Wittchen 1994). Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was = .86. A cut-off of 8–12 has been suggested for screening for mild-moderate mental health problems, and a score of 13+ is reflective of serious mental illness (Kessler et al. 2003). Twenty percent of the current sample obtained a score suggestive of mild-moderate mental health problems, and 10% of the current sample met the clinical cut-off for serious mental illness.

Promoting Relationships and Eliminating Violence Network Assessment Tool—Parent Version—select items (PREVNet tool; PREVNet Assessment Working Group 2008). The PREVNet tool, parent version, is a parent report survey that focuses on bullying perpetration and victimization experiences among children. A select subset of victimization items was used for this study, and definitions were provided for each type of bullying (physical, verbal, social, and cyber). Parents were asked: “How often has your child been bullied in the past 4 weeks?” Parents are also asked: “How often has your child been bullied in the following ways in the past 4 weeks?” with the four types of bullying listed as separate items. For each of the items, parents are asked to choose one of five possible responses: never, once or twice, two or three times, once per week, and several times per week. Parents who indicated that their child had experienced bullying were also asked, “for how long has your child been bullied?” and given the following response options: one week, four weeks, several months, one year, or more than one year.

Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form—Parent Form (NCBRF; Aman et al. 1996). The NCBRF is a parent report scale that assesses problem behaviors among children. Problem behaviors are measured across 66 items and six subscales: Conduct Problems, Insecure/Anxious, Hyperactive, Self-Injury/Stereotypic, Self-Isolated/Ritualistic, and Overly Sensitive. Parents are instructed to indicate the occurrence rate and severity of the problem over the last month. The psychometric properties of this scale have been examined within a sample of children and youth with ASD (Lecavalier et al. 2004). Lacavalier et al. replicated the factor structure originally found by Aman et al. within this sample using confirmatory factor analyses and indicated acceptable internal consistency for the social competence subscales (alpha coefficients range from .63 to .79) and problem behaviors subscales (alpha coefficients range from .71 to .92). In the current study, the internal consistency for problem behaviors subscales were acceptable (alpha coefficients range from .67 to .88).

Autism-Spectrum Quotient—Adolescent Version (AQ; Baron-Cohen et al. 2006). The AQ is a parent report scale that assesses the severity of autistic traits among children and adolescents. This scale consists of 50 items and five subscales: social skills, attention switching, attention to detail, imagination, and communication. Each subscale includes 10 behavior statements that parents are asked to rate using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from definitely agree (0) to definitely disagree (3). Items are subsequently coded dichotomously into 0 and 1 to reflect the absence or presence of each symptom. Total AQ scores reflect the sum of all items; the lowest possible score (i.e., 0) suggests no autistic traits and the highest possible score (50) indicates high levels of severity for all traits. In this study, only participants with an AQ score at or above 30 were included in the analyses. Previous research has found that 90% of adolescents with ASD scored at least 30, while none of the controls scored in that range (Baron-Cohen et al. 2006). The AQ has strong test–retest reliability (r = .92, p < .001) and strong internal consistency for the overall measure (alpha coefficient = .79; Baron-Cohen et al. 2006). Internal consistency for the overall scale was also high in the current study (alpha coefficient = .82).

Results

Frequency and Length of Victimization

Seventy-seven percent of parents reported that their child had been bullied at school within the last month, with 11% reporting victimization only once, 23% reporting victimization two or three times, 13% reporting victimization once per week, and 30% reporting victimization two or more times per week. Among the parents who reported victimization in the last month, length of the victimization was reported as follows: 6% one week, 2% two month, 20% several months, 9% one year, 54% more than one year, and 9% reported not applicable. Of the 9% who reported not applicable, 83% had reported their child was bullied three or fewer times per month. Table 1 presents the rates of physical, verbal, social, and cyber forms of victimization. Sixty-eight percent of youth experienced more than one form of bullying.

Children were categorized into three groups of differing levels of victimization based on parent responses to the question, “how often has your child been bullied in the past 4 weeks?” (regardless of the type of bullying), to explore potential differences in mental health problems associated with victimization. The ‘no victimization’ group included children of parents who responded with “never” (22%), the ‘low victimization’ group included children of parents who responded with “once” or “two or three times” (32%), and the high victimization group included children of parents who responded “once per week” or “several times per week” (46%).

Pearson’s product moment correlation indicated that child age was not associated with frequency of victimization as measured by parent responses to the question, “how often has your child been bullied in the past 4 weeks?” (r = −.10, p = .13). A 2 × 3 chi-square test showed that the relationship between child gender and victimization group (no, low, high) was also not significant [χ 2(2) = 1.34, p = .51]. Four additional 2 × 2 chi-square tests with Bonferroni correction (adjusted alpha level of .05/4 = .01) were conducted to explore the relationship between child gender and dichotomous victimization groupings (any versus none) for each of the four forms of victimization. Child gender was related to cyber [χ 2 (1) = 20.35, p < .001] forms of victimization only, with a significantly higher proportion of girls than boys experiencing cyber forms of victimization. Child gender was not related to physical [χ 2 (1) = 4.68, p = .03], verbal [χ 2 (1) = 0.86, p = .36], or social [χ 2 (1) = 0.70, p = .40] forms of victimization.

Relationship Between Victimization and Mental Health

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to investigate potential differences in child mental health problems across three victimization levels. The independent variable represented the categorization of children’s level of victimization as reported by their parents (no, low, or high) and the dependent variables included the NCBRF problem behavior subscales (Conduct Problems, Insecure/Anxious, Hyperactive, Self-Injury/Stereotypic, Self-Isolated/Ritualistic, and Overly Sensitive).

There was a significant multivariate effect of victimization group on the mental health variables, F(12, 278) = 2.77, p < .001, partial eta squared = .11. Univariate analyses indicated that all of the NCBRF subscales, with the exception of Self-Isolated/Ritualistic, were significantly different across groups. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and univariate analyses of the dependent variables. Post hoc testing with Sidak Bonferroni adjustment was conducted and significant differences among the three groups were indicated for all subscales with the exception of Conduct Problems. Children classified in the ‘no victimization’ and ‘low victimization’ groups reported significantly lower scores than children in the ‘high victimization’ group on the Insecure/Anxious (p’s < .001), Hyperactive (p’s < .01), Self-injury/Stereotypic (p’s < .05), and Overly Sensitive (p’s < .001) subscales. No significant differences were found between children in the ‘no victimization’ and ‘low victimization’ groups.

Individual and Contextual Variables as Predictors of Victimization

Binomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the prediction of victimization by individual and contextual variables. Children were categorized again based on their parent-reported level of victimization, this time into dichotomous groups: any victimization (70%) and no victimization (30%; parents who reported that their child was only bullied once were included in this group). Individual variables included child gender, child age (reverse coded to reflect that younger age may be a risk factor), severity of child’s social skills deficits (AQ social skills subscale), severity of child’s communication difficulties (AQ communication subscale), child internalizing mental health problems (NCBRF insecure/anxious subscale), and child externalizing mental health problems (NCBRF conduct problems subscale). Contextual variables included parent mental health problems (total K6 score) and child’s number of friends at school (reverse coded to reflect that fewer friends may represent a risk factor).

The model was significant, χ 2 = 59.40, df = 8, p < .001, and correctly predicted 77% of participants. As shown in Table 3, child age, communication difficulties and internalizing mental health problems independently predicted victimization, as did parent mental health problems and the child having fewer friends at school. Compared to children who were not victimized, those who were victimized were approximately 5 times more likely to have higher levels of communication difficulties, 11 times more likely to have higher levels of internalizing mental health problems, and 3 times more likely to have a parent with higher levels of mental health problems. Children who were victimized were also more likely to be younger and have fewer friendships within school than children who were not victimized.

A second binomial logistic regression was conducted to further examine the relationships between the predictors and victimization. This second regression included the same individual and contextual predictor variables as the original regression model, but the dichotomous grouping variable was as follows: no or low victimization (54%) and high victimization (46%). Since the post-hoc tests within the above MANOVA indicated that the no and low victimization groups were similar to each other, we wanted to briefly explore whether predictors of high victimization are different than predictors of any victimization. The results of these additional analyses were similar to those of the initial regression model. The predictors did not change with respect to significance, direction or rough magnitude; therefore, the results of these analyses are not included as they do not provide additional information.

Discussion

As expected, victimization was reported to occur at higher rates among children with ASD when compared to the general population. Difficulties developing and maintaining friendships, and social difficulties more generally, among children with ASD likely play an important role in placing these children at greater risk for victimization, as these difficulties are associated with victimization in the general population (Delfabbro et al. 2006; Forero et al. 1999; Nansel et al. 2001; Williams and Guerra 2007). Children with poor social skills and few friends are marginalized and unprotected within the social group and are vulnerable to the abuse of power by peers (Delfabbro et al. 2006). In addition, given the cross-sectional nature of these results, experiences with victimization may exacerbate social difficulties among children with ASD. Children with ASD may also be targeted by aggressive peers because of atypical interests and/or behaviors, as well as intense emotional and/or behavioral reactions to victimization that encourage the child who is bullying (Gray 2004). Research indicates that maladaptive emotion regulation and aggression-focused coping in response to peer victimization may represent risk factors for chronic victimization (Mahady-Wilton et al. 2000).

Victimization within this sample was reported most often to be verbal or social in nature. This is consistent with the bullying literature, as verbal and relational forms of bullying are consistently more prevalent than physical forms of bullying among children and youth (Craig and Pepler 1997; Scheithauer et al. 2006; Woods and White 2005). Verbal and social forms of bullying appear to become more common once children are old enough to realize that these forms are equally (or more) effective in hurting others and more covert than physical forms of bullying, which decrease with age (Rivers and Smith 1994; Woods and White 2005). Verbal and social forms of bullying are also less conspicuous and more likely to avoid detection from adults, compared to physical forms of bullying (Sutton et al. 1999).

Frequent victimization was related to many mental health problems among children with ASD. Children who experienced high levels of victimization (once or more per week) were rated by their parents as having higher levels of anxiety, hyperactivity, self-injurious and stereotypic behaviors, and over sensitivity than children who experienced no victimization or experienced low levels of victimization (i.e., less than once per week). These findings are consistent with international bullying literature, which indicates that children who are victimized are more likely than peers to exhibit various internalizing and externalizing mental health problems (Delfabbro et al. 2006; Grills and Ollendick 2002; Haynie et al. 2001; Mitchell et al. 2007; Nansel et al. 2001, 2003, 2004; Ybarra and Mitchell 2004, 2007). Victimization is stressful for children and negatively impacts self-concept, both of which are associated with mental health problems (Grills and Ollendick 2002; Marsh et al. 2001; Nansel et al. 2004; O’Moore and Kirkham 2001). This relationship is likely bidirectional, however, as children with mental health problems tend to be at risk for victimization (Fekkes et al. 2006).

Victimization status was associated with several individual and contextual factors when controlling for age and gender. Compared to children who were not bullied, those who were victimized were approximately 5 times more likely to have higher levels of child communication difficulties. Communication difficulties may place children with ASD at risk for victimization because these difficulties impede their ability to engage with peers and form friendships (Delfabbro et al. 2006). Communication impairments in youth with ASD may also place them at increased risk for victimization because research indicates that assertiveness and healthy communication are protective factors for victimization and poorer communication results in less effective advocacy (Arora 1991; Sharp and Cowie 1994). The implications of this finding are likely impacted by the age of the child, as communication demands within social situations differ across stages of development. The average age of the children in this study was 11 years old, an age at which conversational skills, rather than play skills, start to become more important during peer interactions (Parker et al. 2006). Again, this relationship may be bidirectional, with victimization experiences exacerbating communication difficulties.

Children who were bullied, compared to those who were not, were also 11 times more likely to have higher levels of child internalizing mental health problems. As mentioned, there is evidence of a bidirectional relationship between internalizing mental health problems and victimization within the bullying literature (Fekkes et al. 2006). On the one hand, victimization is stressful for children, especially considering the value children place on friendships and acceptance from peers, and such stress can lead to mental health problems. On the other hand, mental health problems can make children appear more vulnerable to aggressive peers, placing them at risk for victimization. Children who experience internalizing mental health problems tend to exhibit less assertiveness and self-confidence than their peers, and it has been suggested that aggressive children likely believe that these children will not stand up for themselves if/when victimized (Crick et al. 1999; Fekkes et al. 2006).

Children who were victimized were also more likely to be younger than those who were not victimized. This finding is consistent with research on the development of bullying (Nansel et al. 2001; Pepler et al. 2006a, 2008). It appears that many children and youth who victimize peers eventually desist during adolescence, perhaps due to increased levels of empathy and decreased tolerance for people who are hurtful and mean (Galambos et al. 2003). It is also important to consider that these findings are based on parent report. Perhaps the current age-related finding reflects the fact that parent reports of bullying are more accurate for younger children, since these parents tend to be more involved in their child’s social lives. Parents of older children may not observe or by informed of their child’s experiences with bullying, as these children are developmentally becoming more independent from their parents.

Contextual factors also emerged as predictors of victimization. Children who were bullied, compared to those who were not, were 3 times more likely to have a parent with greater mental health problems. Parents with greater mental health problems may be less able to create an optimal social environment for children at home and to advocate for appropriate support for their child at the school, especially when their child with an exceptionality requires additional supports to change the dynamics at school that are facilitating the bullying experiences (Waylen and Stewart-Brown 2010). Alternatively, or perhaps in addition, parent knowledge of child victimization may impact parent mental health. Children who were victimized were also more likely to have fewer friendships within school than those who were not victimized. Regardless of whether they are typically developing or diagnosed with ASD, children with few friends and poor peer relationships are at the margins of the social group and are vulnerable to the abuse of power by peers (Nansel et al. 2001; Delfabbro et al. 2006).

Implications for Prevention and Intervention

Adults are responsible for promoting healthy relationships among children. Parents and teachers, along with any other adults involved with children, must work towards creating positive environments to promote positive peer interactions and minimize the potential for negative peer interactions such as bullying (Cummings et al. 2006). Social activities among children have the potential for either positive group dynamics (inclusion, caring, etc.) or negative group dynamics (exclusion, aggression, etc.). It is important for adults to provide structure in children’s lives such that aggressive and bullying behaviors cannot develop or thrive (Pepler and Craig 2007). For example, when teams are being chosen for sports, it is best to assign children to teams rather than choose team captains and allow them to choose because of the natural processes in children’s groups to associate with high status and similar children, so marginalized children are typically excluded. As another example, it is best to assign seating in classrooms rather than let the children choose with whom they would like to sit. In the former options of these two examples, the use of social architecture is preventative in nature, protecting children from opportunities when bullying may occur and facilitating healthy relationships (Pepler and Craig 2007). Through positive social architecture, marginalized children who are vulnerable for victimization are protected and social inclusion in maximized. In addition, it is important for adults to remember that they are role models for children and to act accordingly. If adults are using their own power aggressively with others (adults or children), children will likely learn these behaviors are acceptable (Pepler et al. 2009).

It is also crucial that adults are aware of peer dynamics among children (Pepler and Craig 2007). Peers are present during roughly 85% of bullying episodes and hold the power to either prolong or stop bullying episodes (Craig and Pepler 1995, 1997; Craig et al. 1997, 2007; O’Connell et al. 1999; Hawkins et al. 2001; Olweus 1993; Salmivalli et al. 1996). When peers gather to watch a bullying episode, the episode tends to last longer because the child who is bullying is reinforced by the attention (O’Connell et al.1999). If peers intervene, however, the bullying episode will stop immediately over 50% of the time (Fekkes et al. 2005; Hawkins et al. 2001). Salmivalli et al. (1996) found that most children play a definable participant role during bullying episodes. Through peer nomination procedures, they identified four participant roles (in addition to the child bullying and the child being victimized) that witnesses take on during bullying episodes: assistant to the bully, reinforcer of the bully, outsider, and defender of the victim (Salmivalli et al. 1996). In one study, roughly 20–30% of witnesses assisted or reinforced the bullying, while 26–30% were outsiders, and roughly 20% were defenders of the victims (Salmivalli et al. 1998). It is important to enhance children’s capacities to be defenders and promote their awareness of their roles in bullying to reduce reinforcement and maintenance of bullying dynamics (O’Connell et al. 1999). Salmivalli and colleagues have developed a highly successful bullying intervention program that reduces bullying and victimization, as well as increases empathy, defending, and peer support for children who are victimized by helping teachers with shifting the participant roles among their students so that peers are more supportive of the child being victimized during bullying episodes (Kärnä et al. 2011). Early identification of negative peer interactions along with intervention to facilitate positive interactions ensures that negative behavior patterns among children do not become entrenched.

Educators can actively discuss exceptionalities and disabilities among children. These discussions, along with modelling an appreciation for each child as a valued member of the class with many attributes, one of which may be a disability, promote inclusiveness within the peer group as children tend to avoid peers who are different unless they are actively taught otherwise (Cummings et al. 2006). Roberts and Smith (1999) assert that typically developing children develop attitudes about peers with disabilities based on the degree of their knowledge about the disability and their observations and perceptions of adults’ attitudes and expectations regarding disabilities and inclusion. These adult attitudes and expectations may be obvious, but can also be inadvertently communicated through nonverbal cues (Cummings et al. 2006). For example, adult silence regarding a child’s disability (i.e., lack of acknowledgement and lack of overt support) can breed a sense of shame among children regarding their disabilities (Cummings et al. 2006; Katz 2003; Weinstein et al. 2004).

When a child is being bullied, particularly a child with a disability, adult support is crucial. Through scaffolding, adults can support children to acquire and develop important social skills such as: adaptive emotional and behavioral regulation strategies and coping skills, ignoring peer provocation, identifying and engaging with supportive peers, problem solving, and communicating assertively (Cummings et al. 2006). Recent research supports the effectiveness and importance of parent-assisted learning with respect to developing social skills among children with ASD (Frankel et al. 2010; Laugeson et al. 2009). This relationship scaffolding, individualized for each child to capitalize on his or her strengths and support weaknesses, can help the child develop coping skills that may reduce the impact of the bullying on the victimized child (or at least appear that way) and in turn reduce the likelihood of bullying. It is important to encourage children to seek help from a trusted adult, and continue to seek help until they find an adult who is willing to listen and offer protection and support. Once the adult understands the particulars of the bullying episodes (e.g., when and where), safe places and safe people can be discussed to minimize the risk for bullying to occur (Cummings et al. 2006).

Our findings indicate that many children with ASD are victimized frequently and chronically over large periods of time. This is especially concerning, as repeated victimization can lead to reduced self-confidence and faith in others (Salmivalli et al. 2005). Researchers and clinicians recommend that children who experience chronic victimization over time, as well as their families, be referred to mental health agencies for support (Cummings et al. 2006; Kaltiala-Heino et al. 1999; Kumpulainen et al. 2001). Empirically-supported psychotherapy approaches for children and their families can provide intensive scaffolding for relationship skills with which children with ASD likely experience difficulties (Cummings et al. 2006; Mishna 1996a, 1996b, 2003; Pepler 2006). A focus on the individual child, however, is only one piece of the response required to reduce experiences of victimization for vulnerable children. Efforts must be made to ensure that peers are educated and encouraged to include and respect atypically developing children, which can only happen if the responsible adults are proactive in modelling and supporting caring behavior among peers.

Universal bullying prevention programs can also be implemented to involve the whole school in bullying prevention and intervention efforts. These programs have proven effective for reducing bullying and promoting healthy relationships and include the implementation of formal bullying policies for the school (Pepler 2006; Smith et al. 2004). In this type of program, education about the school bullying policies and bullying as a phenomenon are both crucial for all members of the school community. This education focuses on the different types of bullying (physical, verbal, social, cyber), power imbalances inherent in bullying, student (and human) rights for feeling safe, the responsibility of bystanders to support those who are victimized and reporting procedures within the school (Cummings et al. 2006). These programs are most effective when they are continued over many years and integrated into the formal and informal curriculum of the school (Cummings et al. 2006). A recent analysis of change through these universal programs indicates that children who bully at a high and consistent rate require more intensive support, not provided within a universal program; children who are victimized at a high rate require extended intervention experiences to escape abuse at the hands of their peers (Pepler et al. 2006b).

Bullying policies within the Canadian educational system differ across provinces and territories. This is the case because education is controlled at the provincial level, with no framework for organization at the national level. Concerns relating to bullying perpetration in the school environment can be addressed through the Youth Criminal Justice Act at the federal level; however, this Act is appropriately viewed as a last resort. Provincial and territorial governments responsible for education include bullying prevention and intervention policies (and sometimes legislation) in the expectations for their schools. For example, Ontario, the province within which the current study was conducted, has implemented a Safe Schools Strategy that defines bullying and outlines how it must be dealt with at the school level. Specifically, all school staff must report any bullying, harassment, or abuse they witness and principals must inform parents if their child is being victimized. Within Ontario, Bill 212 states that a student who bullies may be suspended from school regardless of whether or not the incident took place on school grounds as bullying is likely to affect the learning environment regardless of where it took place.

Study Limitations

The convenience sampling method that we employed limits the generalizability of the study results. Parents who were not able to access or navigate the internet were likely excluded from this study, as participant recruitment and data collection occurred over the internet. Parents were given the opportunity to request paper and pencil versions of the survey; however, only three exercised this option. Further, this recruitment method may represent a selection bias, as parents of children who have experienced bullying or peer rejection may have been more likely to participate. In addition, the vast majority of parents identified themselves as well educated and European Canadian; therefore, findings may not generalize across diverse cultural groups. Household income was fairly distributed, however. The information collected for this study was based entirely on reports given by one parent in the family, most often the mother. Consequently, these results may not generalize to other caregivers (e.g., fathers, grandparents, step or foster parents, etc.). The diagnostic characterizations within this sample were based on parent report of the child’s diagnosis, as well as cut-off scores for the Autism-Spectrum Quotient. As such, these classifications lack clarification and represent a limitation.

In addition, peer victimization is a personal experience and parent report has some limitations. Sole reliance on parent report makes the assumption that parents are completely aware of their child’s experiences with bullying, as well as the nature of these experiences. In fact, parents may not be privy to any or all incidences taking place outside their direct observation, especially among older children (Charach et al. 1995). In addition, parents may be more aware of, and therefore more likely to report, more overt forms of bullying (e.g., physical) compared to other more covert forms (e.g., social). Not only are the more overt forms easier for parents and teachers to identify during a child’s interactions with peers; they often require more action on the part of the school (i.e., notification of parents, safety planning for the child, etc.). A final limitation of this study is the lack of information about where the bullying took place (e.g. school or community).

Conclusions

Bullying experiences are very common among children with ASD, with victimization rates that are twice as high as those found in the general population. These bullying experiences are associated with various mental health problems. Based on parents’ reports, we have been able to develop a profile of youth with ASD who are at risk for being victimized—a profile that is consistent with research on typically developing youth who are victimized. Children with ASD at greatest risk for experiencing bullying are those who are younger in age, have greater communication difficulties, have internalizing mental health problems, have fewer friends at school, and have parents with greater mental health problems. The parents’ reports also indicated that when bullying occurs in these children, it occurs frequently and tends to endure over a long period of time. The tremendous deleterious effect of such chronic victimization calls for immediate systemic interventions that change the social architecture of the school environment (Pepler and Craig 2007) and involve the child, school system, and family. A number of authors have suggested comprehensive interventions (Gray 2004), and it is critical that future research evaluate their effectiveness and determine preventive measures that can work for these vulnerable youth.

References

Aman, M. G., Tassé, M. J., Rojahn, J., & Hammer, D. (1996). The Nisonger CBRF: A child behavior rating form for children with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 17, 41–57.

Arora, T. (1991). The use of victim support groups. In P. K. Smith & D. A. Thompson (Eds.), Practical approaches to bullying. London: David Fulton.

Baron-Cohen, S., Hoekstra, R., Knickmeyer, R., & Wheelwright, S. (2006). The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ)—adolescent version. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 343–350.

Bauminger, N., & Kasari, C. (2000). Loneliness and friendship in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development, 71, 447–456.

Brown, B. B., Eicher, S. A., & Petrie, S. (1986). The importance of peer group (“crowd”) affiliation in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 9, 73–96.

Carter, S. (2009). Bullying of students with Asperger Syndrome. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 32, 145–154.

Charach, A., Pepler, D., & Ziegler, S. (1995). Bullying at school: A Canadian perspective. Education Canada, 35, 12–18.

Craig, W., & Pepler, D. (1995). Peer processes in bullying and victimization: An observational study. Exceptionality Education Canada, 5, 81–95.

Craig, W., & Pepler, D. (1997). Observations of bullying and victimization in the school yard. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 13, 41–60.

Craig, W., Pepler, D., & Atlas, R. (1997). Observations of bullying in the playground and classroom. School Psychology International, 21, 22–36.

Craig, W. M., Pepler, D., & Blais, J. (2007). Responding to bullying: What works? School Psychology International, 28, 465–477.

Crick, N. R., Casas, J. F., & Ku, H. C. (1999). Relational and physical forms of peer victimization in preschool. Developmental Psychology, 35, 376–385.

Cummings, J. G., Pepler, P., Mishna, F., & Craig, W. (2006). Bulling and victimization among students with exceptionalities. Exceptionality Education, 16, 193–222.

Delfabbro, P., Winefield, T., Trainor, S., Dollard, M., Anderson, S., Metzer, J., et al. (2006). Peer and teacher bullying/victimization of South Australian secondary school students: Prevalence and psychosocial profiles. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 71–90.

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I., Fredriks, A. M., Vogels, T., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2006). Do bullied children get ill, or do ill children get bullied? A prospective cohort study on the relationship between bullying and health-related symptoms. Pediatrics, 117, 1568–1574.

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I. M., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2005). Bullying: Who does what, when and where? Involvement of children, teachers and parents in bullying behavior. Health Education Research, 20, 81–91.

Ford, D. H., & Lerner, R. M. (1992). Developmental systems theory: An integrative approach. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Forero, R., McLellan, L., Rissel, C., & Bauman, A. (1999). Bullying behavior and psychosocial health among school students in New South Wales, Australia: Cross sectional study. British Medical Journal, 319, 344–348.

Frankel, F., Myatt, R., Whitham, C., Gorospe, C., & Laugeson, E. A. (2010). A controlled study of parent-assisted Children’s Friendship Training with children having Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 827–842.

Furukawa, T. A., Kessler, R. C., Slade, T., & Andrews, G. (2003). The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychological Medicine, 33, 357–362.

Galambos, N. L., Barker, E. V., & Tilton-Weaver, L. C. (2003). Canadian adolescents’ implicit theory of immaturity: What does childish mean? New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 77–90.

Gray, C. (2004). Gray’s guide to bullying parts I-III. Jenison Autism Journal, 16(1), 2–19.

Grills, A. E., & Ollendick, T. H. (2002). Peer victimization, global self-worth, and anxiety in middle school children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 59–68.

Hawkins, D. L., Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. M. (2001). Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development, 10, 512–527.

Haynie, D. L., Nansel, T., Eitel, P., Crump, A. D., Saylor, K., & Yu, K. (2001). Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups of at-risk youth. Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 29–49.

Kaltiala-Heino, R., Rimpela, M., Marttunen, M., Rimpela, A., & Rantanen, P. (1999). Bullying, depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents: School survey. British Medical Journal, 319, 348–356.

Kaltiala-heino, R., Rimpela, M., Rantanen, P., & Rimpela, A. (2000). Bullying at school: An indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 661–674.

Kärnä, A., Voeten, M., Little, T., Poskiparta, E., Kaljonen, A., & Salmivalli, C. (2011). A large-scale evaluation of the KiVa antibullying program: Grades 4-6. Child Development, 82, 311–330.

Katz, P. A. (2003). Racists or tolerant multiculturalists? How do they begin? American Psychologist, 58, 897–909.

Kessler, R. C., & Ustun, T. B. (2004). The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world health organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13, 93–121.

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., et al. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32, 959–976.

Kessler, R. C., Barker, P. R., Colpe, L. J., Epstein, J. F., Gfroerer, J. C., Hiripi, E., et al. (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 184–189.

Kumpulainen, K., Rasanen, E., Henttonen, I., Almqvist, F., Kresanov, K., Linna, S., et al. (1998). Bullying and psychiatric symptoms among elementary school-age children. Child Abuse and Neglect, 22, 705–717.

Kumpulainen, K., Räsänen, E., & Puura, K. (2001). Psychiatric disorders and the use of mental health services among children involved in bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 27, 102–110.

Laugeson, E. A., Mogil, C. E., Dillon, A. R., & Frankel, F. (2009). Parent-assisted social skills training to improve friendships in teens with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 596–606.

Lecavalier, L., Aman, M. G., Hammer, D., Stoica, W., & Mathews, G. L. (2004). Factor analysis of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 709–721.

Little, L. (2002). Middle-class mothers’ perceptions of peer and sibling victimization among children with Asperger’s syndrome and nonverbal learning disorders. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 25, 43–57.

Mahady-Wilton, M., Craig, W. M., & Pepler, D. J. (2000). Emotional regulation and display in classroom bullying: Characteristic expressions of affect, coping styles and relevant contextual factors. Social Development, 9, 226–245.

Marsh, H. W., Parada, R. H., Yeung, A. S., & Healey, J. (2001). Aggressive school troublemakers and victims: A longitudinal model examining the pivotal role of self-concept. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 411–419.

Mishna, F. (1996a). In their own words: Therapeutic factors for adolescents with learning disabilities. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 46, 265–273.

Mishna, F. (1996b). Finding their voice: Group therapy for adolescents with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 11, 249–258.

Mishna, F. (2003). Learning disabilities and bullying: Double jeopardy. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 4, 336–347.

Mitchell, K. J., Ybarra, M., & Finkelhor, D. (2007). The relative importance of online victimization in understanding depression, delinquency, and substance use. Child Maltreatment, 12, 314–324.

Molcho, M., Craig, W., Due, P., Pickett, W., Harel-Fisch, Y., Overpeck, M., et al. (2009). Cross-national time trends in bullying behaviour 1994–2006: Findings from Europe and North America. International Journal of Public Health, 54, 225–234.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 285, 2094–2100.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Haynie, D. L., Ruan, J., & Scheidt, P. C. (2003). Relationships between bullying and violence among US youth. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 157, 348–353.

Nansel, T. R., Craig, W., Overpeck, M. D., Saluja, G., Ruan, J., & The Health Behavior in School-aged Children Bullying Analyses Working Group. (2004). Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 158, 730–736.

O’Connell, P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: Insights and challenges for intervention. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 437–452.

O’Moore, M., & Kirkham, C. (2001). Self-esteem and its relationship to bullying behaviour. Aggressive Behavior, 27, 269–283.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Oxford: Blackwell.

Orsmond, G. I., Krauss, M. W., & Seltzer, M. (2004). Peer relationships and social and recreational activities among adolescents and adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 245–256.

Parker, J. G., Rubin, K. H., Erath, S. A., Wojslawowicz, J. C., & Buskirk, A. A. (2006). Peer relationships, child development, and adjustment: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology (2nd ed., pp. 419–493). New Jersey: Wiley.

Pellegrini, A. D., & Bartini, M. (2000). A longitudinal study of bullying, victimization, and peer affiliation during the transition from primary school to middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 37, 699–725.

Pellegrini, A. D., Bartini, M., & Brooks, F. (1999). School bullies, victims, and aggressive victims: Factors relating to group affiliation and victimization in early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 216–224.

Pepler, D. J. (2006). Bullying interventions: A binocular perspective. Journal of Canadian Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 15, 16–20.

Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. M. (2000). Making a difference in bullying. LaMarsh Research Centre for Violence and Conflict Resolution, Research Report 60. Toronto, Ontario: York University.

Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. M. (2007). Binoculars on bullying: A new solution to protect and connect children. Retrieved from http://www.canadiansafeschools.com/programs/research.htm.

Pepler, D. J., Craig, W. M., Connolly, J. A., Yuile, A., McMaster, L., & Jiang, D. (2006a). A developmental perspective on bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 376–384.

Pepler, D., Jiang, D., & Craig, W. (2006). Who benefits from bullying prevention programs? A mixed model analysis. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development, Melbourne, Australia.

Pepler, D., Jiang, D., Craig, W., & Connolly, J. (2008). Developmental trajectories of bullying and associated factors. Child Development, 79, 325–338.

Pepler, D., Craig, W., & Cummings, J. (2009). Conclusions: Steps to respect for everyone by everyone. In W. Craig, D. Pepler, & J. Cummings (Eds.), Rise up for respectful relationships: Prevent bullying (pp. 199–206). Ottawa, Canada: National Printers.

PREVNet Assessment Working Group. (2008). PREVNet bullying survey: Grades 4–6. Kingston, Canada: PREVNet.

Rivers, I., & Smith, P. K. (1994). Types of bullying behaviour and their correlates. Aggressive Behavior, 20, 359–368.

Roberts, C. M., & Smith, P. R. (1999). Attitudes and behaviour of children towards peers with disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 46, 35–50.

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 1–15.

Salmivalli, C., Lappalainen, M., & Lagerspetz, K. (1998). Stability and change of behaviour in connection with bullying in schools: A two-year follow-up. Aggressive Behavior, 24, 205–218.

Salmivalli, C., Ojanen, T., Haanpää, J., & Peets, K. (2005). “I’m ok but you’re not” and other peer-relational schemas: Explaining individual differences in children’s social goals. Developmental Psychology, 41, 363–375.

Scheithauer, H., Hayer, T., Petermann, F., & Jugert, G. (2006). Physical, verbal, and relational forms of bullying among German students: Age trends, gender differences, and correlates. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 261–275.

Sharp, S., & Cowie, H. (1994). Empowering students to take positive action against bullying. In P. K. Smith & S. Sharp (Eds.), School bullying: Insights and perspectives (pp. 108–131). London: Routeledge.

Smith, P. K., Pepler, D., & Rigby, K. (Eds.). (2004). Bullying in schools: How successful can interventions be?. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press.

Spriggs, A. L., Iannotti, R. J., Nansel, T. R., & Haynie, D. L. (2007). Adolescent bullying involvement and perceived family, peer, and school relations: Commonalities and differences across race/ethnicity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 283–293.

Sutton, J., Smith, P. K., & Swettenham, J. (1999). Social cognition and bullying: Social inadequacy or skills manipulation? British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 17, 435–450.

Wainscot, J. J., Naylor, P., Sutcliffe, P., Tantam, D., & Williams, J. V. (2008). Relationships with peers and use of the school environment of mainstream secondary school pupils with Asperger Syndrome (High-Functioning Autism): A case-control study. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 8, 25–38.

Waylen, A., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2010). Factors influencing parenting in early childhood: A prospective longitudinal study focusing on change. Child: Care, Health and Development, 36, 198–207.

Weinstein, R. S., Gregory, A., & Strambler, M. J. (2004). Intractable self-fulfilling prophecies. American Psychologist, 59, 511–520.

Williams, K. R., & Guerra, N. G. (2007). Prevalence and predictors of Internet bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 14–21.

Wittchen, H. U. (1994). Reliability and validity studies of the WHO–Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): A critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 28, 57.

Woods, S., & White, E. (2005). The association between bullying behavior, arousal levels, and behavior problems. Journal of Adolescence, 28, 381–395.

Ybarra, M. L. (2004). Linkages between depressive symptomology and Internet harassment among young regular Internet users. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 7, 247–257.

Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2004). Online aggressor/targets, aggressors, and targets: A comparison of associated youth characterictics. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 1308–1316.

Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2007). Prevalence and frequency of Internet harassment instigation: Implications for adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 189–195.

Ybarra, M. L., Mitchell, K. J., Wolak, J., & Finkelhor, D. (2006). Examining characteristics and associated distress related to Internet harassment: Findings from the Second Youth Internet Safety Survey. Pediatrics, 118, e1169–e1177.

Acknowledgments

M. Catherine Cappadocia was supported during the preparation of this manuscript by The Provincial Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health at CHEO Graduate Award and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarships Doctoral Award. Jonathan A. Weiss was supported by a New Investigator Fellowship from the Ontario Mental Health Foundation. Debra Pepler was supported by Networks of Centres of Excellence through its support of PREVNet (Promoting Relationships and Eliminating Violence Network).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cappadocia, M.C., Weiss, J.A. & Pepler, D. Bullying Experiences Among Children and Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 42, 266–277 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1241-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1241-x