Abstract

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are characterized by difficulties with social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, and the development and maintenance of interpersonal relationships. As a result, individuals with ASD are at an increased risk of bullying victimization, compared to typically developing peers. This paper reviews the literature that has emerged over the past decade regarding prevalence of bullying involvement in the ASD population, as well as associated psychosocial factors. Directions for future research are suggested, including areas of research that are currently unexplored or underdeveloped. Methodological issues such as defining and measuring bullying, as well as informant validity and reliability, are considered. Implications for intervention are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) tend to be marginalized within the peer group, placing them at high risk for being bullied by peers. These children have difficulties understanding and participating in social interactions and, consequently, developing and maintaining positive peer relationships. In this paper, we review the literature regarding peer victimization (i.e., being bullied by peers) among children and adolescents with ASD. We begin with a brief summary of relevant information about bullying and victimization in the general population. Then, we discuss factors that may place youth at risk for bullying perpetration and victimization, with a focus on youth with ASD. Next, we briefly outline the existing research literature on bullying perpetration and victimization among children with exceptionalities, followed by a comprehensive review of the emerging literature on bullying experiences within ASD populations. Finally, we discuss methodological considerations and limitations within this research area, as well as directions for future research.

Bullying and Victimization in the General Population

Bullying is a relationship problem characterized by recurring aggression that occurs within a relationship that involves a power imbalance (Olweus 1993; Pepler et al. 1999), and typically involves an intent to harm the other person (e.g., Nansel et al. 2001). Among children and adolescents, a power imbalance can occur with respect to a number of variables including physical size, age, social status, intellectual level, and disability status (Olweus 1993; Pepler et al. 2008).

Bullying is common among children. A large-scale international study conducted by the World Health Organization among roughly 134,000 children aged 11–15 years indicated that roughly one-third of children report occasional bullying perpetration or victimization, while a smaller subset (about 10 %) report chronic perpetration or victimization (Molcho et al. 2009). Longitudinal research within Canada supports the presence of this smaller subset of children and adolescents (5–20 %) who experience chronic bullying or victimization throughout their education (Pepler et al. 2008). Using a large, nationally representative sample of over 7,000 American students in grades 6–10, Wang and colleagues examined the prevalence of specific forms of bullying perpetration and victimization within the last 2 months. Within this sample, approximately 54 % reported that they experienced verbal forms of victimization, 51 % reported social forms, 21 % reported physical forms, and 13 % reported cyber forms (Wang et al. 2010). There are a number of methodological inconsistencies across studies that make it difficult to directly compare results from specific studies, including differences in how bullying is defined, the time period under consideration, the methods used (observational vs. questionnaire), and the informant (parent/teacher/self/peer). Nevertheless, studies consistently indicate the bullying is a common problem with a significant impact on development.

Bullying perpetration and victimization are associated with negative outcomes. Perpetration is associated with poor academic commitment and achievement, as well as delinquent behaviours including smoking, substance use, and physical fighting (Forero et al. 1999; Haynie et al. 2001; Ivarsson et al. 2005; Kaltiala-Heino et al. 2000; Nansel et al. 2001, 2003). Victimization is associated with academic difficulties and school avoidance, as well as internalizing mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation (Alsaker and Valkamover 2001; Boivin et al. 1995; Boulton and Underwood 1992; DeRosier et al. 1994; Hanish and Guerra 2002; Kaltiala-Heino et al. 1999; Kochenderfer and Ladd 1996; Myklebust 2002).

Several characteristics may place children and youth at risk for involvement in bullying perpetration, victimization, or both (see meta-analysis by Cook et al. 2010). Within their meta-analysis, Cook et al. (2010) found that both children who reported bullying others and children who reported victimization tended to report symptoms of internalizing and externalizing mental health problems, negative beliefs about themselves, low levels of social competence, and difficulties with problem solving in social contexts. With respect to mental health problems, children who reported bullying others tended to have more externalizing symptoms than internalizing symptoms, whereas the reverse was true for children who reported victimization. In addition, children who reported bullying others indicated negative beliefs about others and higher tendencies to be influenced by peers, whereas children who reported victimization indicated that they had strained relationships within their family, school, and community contexts and experienced high levels of rejection and isolation within the peer group (Cook et al. 2010).

Risk Factors for Bullying and Victimization in ASD Populations

There is a growing body of literature indicating that individuals with special needs, including ASD, intellectual disabilities, learning disabilities (LD), language impairments, and other health care issues, are at significantly higher risk of both victimization and perpetration (Davis et al. 2002; Estell et al. 2009; Norwich and Kelly 2004; Perry et al. 1998; Rose et al. 2009; Saylor and Leach 2009; Sterzing et al. 2012; Van Cleave and Davis 2006). In fact, in an extensive literature review on bullying in special education, the authors noted that several researchers report victimization rates above 50 % among children with special needs (Rose et al. 2011). Psychiatric disorders are also associated with bullying involvement. Kumpulainen et al. (2001) found that 71 % of children who bully, 50 % of children who are victimized, and 77 % of those who have been both bullied and victimized meet criteria for psychiatric disorders (including: ADHD, conduct problems, depression, anxiety), compared with 22 % of those who were not involved in bullying. Several studies indicate that the more restricted the special education placement, the higher the rates of bullying perpetration and victimization, with students in self-contained classrooms exhibiting higher rates of bullying and victimization than students in more inclusive placements in middle and early high school (Mishna 2004; Norwich and Kelly 2004).

Children with ASD may be particularly vulnerable to involvement in bullying as several characteristics of ASD may increase the likelihood of involvement in bullying perpetration and victimization. This risk may ultimately stem from the reduced likelihood of peer support and related protective processes associated with bullying in the general population. Difficulties with forming and maintaining positive peer relationships and friendships place children and adolescents with ASD at risk for victimization. Having friends and/or supportive peers, which many children with ASD lack because of their social difficulties, have been identified as protective factors for bullying (Bauminger and Kasari 2000; Chamberlain et al. 2007; Estell et al. 2009; Hodges and Perry 1999; Martlew and Hodson 1991). This marginalization results in fewer opportunities for many children and adolescents with ASD to engage in social interactions and practice their skills, which further reduces their social skills. Higher-order theory of mind abilities (understanding the thoughts and intentions of others) also predict peer acceptance (Slaughter et al. 2002). Deficits in theory of mind abilities are suggested as a core feature of ASD (Baron-Cohen et al. 1985); thus, these deficits likely place those with ASD at increased risk of bullying involvement. Theory of mind deficits make it more difficult for those with ASD to understand social cues than their typically developing peers, which would increase the likelihood of marginalization and conflict within peer relationships. Further, difficulties understanding the thoughts of others impacts the ability of individuals with ASD to monitor feedback from others about how their behaviour is being perceived, likely increasing the risk of both misunderstandings and becoming a target of victimization. Difficulties with communication may further the risk of victimization for individuals with ASD because assertiveness and effective communication represent protective factors for coping during bullying situations (Arora 1991; Haq and Le Couteur 2004; Sharp and Cowie 1994). If there is a tendency for an individual to exhibit strong emotional and/or behavioural reactions (e.g., visible anxiety or crying) during bullying episodes, which is likely among individuals with ASD given difficulties with emotion regulation, there may be increased risk for victimization in the future, as these reactions have been found to encourage the perpetrator (Boivin et al. 1995; Gray 2004; Mahady Wilton et al. 2000). In addition, restricted interests and stereotyped behaviours that characterize ASD are likely to be perceived by some peers as being odd or different, resulting in an increased risk of being marginalized within the peer group and targeted by aggressive peers (Boivin et al. 1995; Boulton 1999; Dunn et al. 2002; Gazelle and Ladd 2003; Gray 2004; Haq and Le Couteur 2004; Hodges and Perry 1999; Schwartz et al. 1999). Individuals with ASD may also be at risk for bullying perpetration due to their increased likelihood of aggressive responding and limited social-problem solving capabilities; however, they would likely be unaware that they are bullying due to limited insight (Van Roekel et al. 2010).

Review of Literature on Bullying and ASD

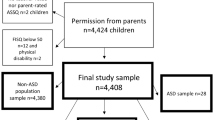

It is widely accepted by clinicians and parents that individuals with ASD experience more victimization than typically developing peers, yet there is a surprising paucity of research in the area. There are even fewer studies that have examined bullying perpetration within this population. See Table 1 for a summary of all published studies in the area.

Rates of Bullying Involvement

Within studies that have included a typically developing comparison group, researchers have identified differences in bullying experiences across groups. Wainscot and colleagues (Wainscot et al. 2008) included a typically developing comparison group in their study of 30 students with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism in mainstream schools. Compared to typically developing students, students with ASD were four times as likely to report being bullied (Wainscot et al. 2008). When asked “what gives you the impression that they [other pupils] don’t like you?,” students with ASD reported more perceived experiences of being ignored, teased, and physically bullied than their typically developing peers. Of those who reported victimization, those with ASD reported significantly more victimization experiences than the typically developing comparison group. More specifically, 40 % of students with ASD reported daily victimization versus 15 % of comparison students, and 33 % of students with ASD reported victimization 2–3 times per week versus 15 % of comparison students. Montes and Halterman (2007) examined bullying experiences using a large-scale nationally representative sample of over 50,000 children and adolescents (aged 6–17 years) from the U.S. National Survey of Children’s Health. They asked mothers how often in the past month their child had bullied, was cruel, or mean to others. Children with autism were four times more likely to bully than children in the general population (44 %). However, the presence of co-morbid ADHD, identified in almost half of the autism sample, moderated this relationship. When ADHD was controlled for, the sample of children with autism were no more likely to bully than the general population. Low income and younger age were also identified as risk factors for bullying in children with autism.

Many of the early studies of bullying and ASD focused on prevalence rates via parent report without including a typically developing comparison group. Little (2002) conducted the first study to examine victimization experiences in individuals with ASD. This study included mothers of 411 children (aged 4–17) with Asperger syndrome or non-verbal LD. The overall prevalence rate for victimization was 94 %, with almost 75 % of the mothers reporting that their child had been hit in the past year and 75 % reporting that their child had experienced emotional bullying (Little 2002). In comparison, victimization rates are typically around 30 % in the general population (e.g., Molcho et al. 2009). Peer shunning was also very common and related to victimization, with the majority of the children receiving one or fewer birthday party invitations in the last year and being picked last for team sports. These results highlight the potential bidirectional relationship between marginalization and victimization in children with ASD. Carter (2009) also examined victimization through parent reports among 34 children, 5–21 years with ASD. The rate of peer victimization within the past year in this study was just under 65 %; in addition, 47 % of parents reported that their child had been hit by ‘peers or siblings’ and 44 % reported their child was picked on by peers. Van Roekel et al. (2010) investigated reports of bullying and victimization in a sample of 230 teens with ASD within the past month. Ratings were completed by children, peers, and teachers. There were discrepancies across informants, but teacher-reported rates were generally consistent with Montes and Halterman (2007). The percentage of students with ASD found to be involved in bullying perpetration more than once a month was 46 % as rated by teachers, 15 % as rated by peers, and 19 % according to self-report. Prevalence of monthly (or more frequent) victimization of students with ASD showed a similar pattern of discrepancy, with victimization occurring in 30 % of students as rated by teachers, 7 % as rated by peers, and 17 % according to self-report.

More recently, Cappadocia et al. (2012) conducted an online parent-report study of victimization and mental health among 192 children and adolescents with ASD within the past month. The majority (80 %) of the children were in fully inclusive classrooms. Overall, 77 % of parents reported that their child had experienced at least one occurrence of victimization within the past month, with 46 % reporting victimization at least once per week. Among those who reported that their child had experienced victimization within the past month, 63 % noted that it had been occurring for at least 1 year. Social bullying (e.g., exclusion and gossip about the child) was the most commonly reported form of victimization, reported by 69 % of parents with 39 % reporting weekly or more frequent occurrences. Verbal bullying (e.g., teasing and making threats) was also common, with 68 % of the sample reporting at least one occurrence within the past month, and 37 % reporting weekly or higher frequency. Physical bullying was reported less often by 42 % of the sample, with 15 % of the sample reporting weekly or more frequent occurrences. These results are generally consistent with earlier results from Little (2002) and Carter (2009). Together these studies indicate that children with ASD experience very high levels of victimization at the hands of their peers when compared to rates found in the general population, which may compound their social-emotional difficulties.

Researchers have also explored rates of cyber forms of bullying and victimization within this population. Cappadocia et al. (2012) found that rates of cyber bullying were quite low, with 10 % of parents of children with ASD reporting this form of victimization. These results are similar to rates with a large US sample of the general population (Wang et al. 2010). Didden et al. (2009) also examined cyber bullying among 114 adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities (some of whom had an ASD) in special education settings and found similar results, with few adolescents (4–9 %) reporting victimization within the past week. Similarly, Kowalski and Fedina (2011) investigated child and parent reports of cyber bullying among 42 children and adolescents (aged 10–20 years) diagnosed with ADHD and/or Asperger syndrome. Among those parents who felt confident reporting on cyber behaviours (12 % reported that they did not know), 3 % reported perpetration and 15 % reported victimization within the past 2 months. Slightly higher rates were found using child report (6 % perpetration and 21 % victimization). Results from studies on cyber bullying are further limited by the fact that there are generally fewer possible informants available than can be found in a school environment. Cyber bullying reporting is generally limited to child report, and parent report (if the child has disclosed to them).

Researchers have further explored differences in bullying experiences among children with ASD, children with other special needs, and typically developing children. Symes and Humphrey (2010) found significant differences between the rate of perceived victimization reported by students with ASD relative to both typically developing peers and peers with dyslexia, while differences between the dyslexia and typically developing groups were not significant. The authors conclude that children with ASD are at particularly high risk of victimization, even relative to peers with special education needs. A self-report survey of over 300 children and adolescents with a variety of special health care needs including ASD, ADHD, LD, mood disorders, and cystic fibrosis, was conducted to examine bullying and victimization in these populations relative to a typically developing control group (Twyman et al. 2010). Consistent with Symes and Humphrey (2010), participants with ASD had elevated rates of perceived victimization relative to the control group and compared to those with other health care needs. Those with ADHD or LD (in contrast with Symes and Humphrey’s findings) were also found to have higher rates of victimization. Rowley et al. (2012) also found that rates of victimization were higher among those with ASD and those with other special education needs relative to UK norms. They also found higher rates in the ASD group relative to the special education needs group when rated by parents, but not teachers. It may be that those with special educational needs are at greater risk of victimization than their peers due to their deficits in social competence rather than being viewed as ‘different.’ Most recently, Sterzing et al. (2012) reported on rates of peer victimization, perpetration, or both in 900 adolescents with ASD compared to those with intellectual disability, speech/language impairments, and LD, using the U.S. National Longitudinal Transition Study. They found higher rates of victimization across all groups compared with the general population. A total of 46 % of parents of those with ASD reported victimization, 15 % reported involvement in perpetration, and 9 % of adolescents with ASD were reported to be involved in both victimization and perpetration within the past school year. Parents of those with ASD reported similar rates of victimization as those with other disabilities, and those with intellectual disability experienced the highest rates of victimization. Rates of perpetration were similar to national averages, and were consistent across groups, with the exception of higher rates among those with speech and language impairment.

Associated Factors

More recently, researchers have begun to look at social, emotional, cognitive and behavioural correlates of bullying among children with ASD. In a parent-report survey, Sofronoff et al. (2011) found that higher levels of social vulnerability (e.g., naïveté, trust, etc.), anxiety, anger, and behaviour problems, as well as lower levels of social skills, predicted peer victimization when examined together among 133 children (aged 6–16) with Asperger syndrome. Only social vulnerability independently predicted peer victimization, however. In an online survey of 10 parents of adolescents and adults with Asperger syndrome (mean age = 20 years), Shtayermman (2007) found that severity of Asperger syndrome symptomatology, but not depressive or anxiety symptomatologies, was related to peer victimization. Although sample size limits the generalizability of these results, lower levels of Asperger syndrome symptomatology were associated with higher levels of victimization, which the author suggests may come from the independence and lack of attention from adults (e.g., teachers) among high functioning individuals. A larger study conducted by Rowley et al. (2012) yielded results that were parallel; children with ASD who experienced less social impairment also reported higher levels of perpetration and victimization. In contrast, Sterzing et al. (2012) found victimization was related to lower social skills in those with ASD. They also found that victimization was more likely in those with ASD with some conversational ability (little or no trouble carrying on a conversation) relative to those with no ability to maintain conversations.

Frequent victimization has also been related to many mental health problems among children with ASD. Children who experience high levels of victimization (once or more per week) tend to exhibit higher levels of anxiety, hyperactivity, self-injurious behaviors, stereotypic behaviors, and elevated emotional sensitivity when compared to children who experience no victimization or low levels of victimization (i.e., less than once per week; Cappadocia et al. 2012). Consistent with these results, a large-scale study of 1,221 parents of children with ASD, found that children who were frequently victimized were more likely to exhibit internalizing problems, while those involved in perpetration had higher rates of emotional regulation difficulties (Zablotsky et al. 2013). Further, these researchers found that children with ASD with conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder were more likely to have been involved in perpetration, while those with depression or ADHD were more involved in victimization. Children involved in both victimization and perpetration were more likely to have conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, or ADHD. Another study also found that the presence of ADHD was a significant predictor of victimization and perpetration in those with ASD (Sterzing et al. 2012). Shtayermman found that within a sample characterized by high levels of peer victimization, 20 % of participants met diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder, 30 % met diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, and 50 % exhibited clinically significant levels of suicidal ideation (as measured on the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire, Reynolds, 1991). Kowalski and Fedina (2011) found that rates of anxiety and depression were lower among those individuals with Asperger syndrome or ADHD who were not involved in bullying when compared to individuals who reported perpetration or victimization. These researchers did not find a similar pattern of results with respect to cyber bullying.

Rieffe and colleagues examined relationships between bullying and victimization and experiencing basic emotions (i.e., fear and anger) and moral emotions (i.e., shame and guilt) among 64 children with ASD and 66 typically developing controls, aged 9–14 years (Rieffe et al. 2012). Regression analyses revealed that in both groups, bullying perpetration was positively associated with anger and negatively associated with guilt. Among typically developing children only, victimization was positively associated with fear, while among children with ASD only, victimization was positively associated with anger. These researchers suggest that, unlike typically developing children, anger dysregulation plays an important role in victimization for children with ASD. They propose that this might be related to the emotional reactivity characteristic of many children with ASD. When provoked, those with ASD may display their anger in an overtly visible manner, thus prompting further victimization.

Van Roekel et al. (2010) included a social information processing component in their study of bullying. Adolescents with ASD watched 14 video clips that contained either bullying situations or positive social interactions and were asked to report whether the clip featured physical, verbal, or relational bullying. The researchers examined rates of false positives (reporting bullying while watching non-bullying video clips) and false negatives (reporting no bullying while watching bullying clips). Overall, the researchers found that their sample of adolescents with ASD reported very few errors on the video clips and demonstrated performance comparable to the general population. Students who had high levels of teacher- and self-reported victimization were more likely to misinterpret positive social interaction video clips as involving bullying, although the effect sizes were small. The more participants were involved in bullying perpetration, as rated by teachers and peers, the more likely they were to misinterpret bullying scenarios as not involving bullying.

Humphrey and Symes (2010) conducted the only qualitative study of bullying among children with ASD to date. These researchers used semi-structured interviews with 36 children with ASD (11–16 years old) to conduct a thematic analysis to develop a theoretical framework for understanding how children with ASD respond to bullying. The following response strategies emerged: seeking help from teachers (most common), enlisting support from friends, asking parents for help (as a last resort), and dealing with it alone (e.g., ignoring or retaliating with violence). The response strategies were chosen largely based on the child’s perceived likelihood that it would be effective in stopping the bullying, based on past experience. The likelihood that children would seek help from others was mediated by two factors: relationship history (i.e., whether someone could be counted on to help), and barriers including traits associated with ASD, lack of trust in others, and a general desire for solitude.

Discussion

Bullying is a pervasive problem among children that is associated with many negative academic, social, and psychological outcomes. Within the general population, bullying involvement is common, with approximately one-third reporting occasional involvement with victimization or perpetration and roughly one-tenth reporting chronic victimization (Molcho et al. 2009). Due to their social, communication, and behavioural difficulties, children and adolescents with ASD are at an increased risk for bullying involvement when compared with typically developing peers.

Taken together, the studies reviewed confirm that children and youth with ASD are experiencing increased rates of perceived physical, verbal, and relational forms of bullying relative to the general population (Cappadocia et al. 2012; Carter 2009; Kowalski and Fedina 2011; Little 2002; Rowley et al. 2012; Sofronoff et al. 2011; Symes and Humphrey 2010; Twyman et al. 2010; Van Roekel et al. 2010; Wainscot et al. 2008; Zablotsky et al. 2013). Consistent with the general population, cyber-victimization rates are quite low, relative to other forms of bullying (Didden et al. 2009; Cappadocia et al. 2012; Kowalski and Fedina 2011). Children and youth with ASD also experience higher rates of victimization than peers with other mental and physical health care needs, based on self and parent report (Rowley et al. 2012; Symes and Humphrey 2010; Twyman et al. 2010). Further research is need to determine if those with ASD have more bullying involvement than those with ADHD or LD, as there are inconsistencies in the literature. Symes and Humphrey (2010) found those with ASD were at an elevated risk of bullying involvement relative to those with LD, while Twyman et al. (2010) found similar rates among those with ASD, ADHD, and LD. Sterzing et al. (2012) found similar rates across those with ASD and LD, and found increased victimization in those with intellectual disability, as well as increased perpetration in those with speech and language problems. It appears that rates of victimization tend to be lower in schools that are restricted to ASD students (as reported by students and parents, but not teachers; Rowley et al. 2012; Wainscot et al. 2008).

The current review indicates that students with ASD tend to exhibit risk factors and lack protective factors associated with victimization in the general population. Many of these risk factors, and lack of protective factors, reflect characteristics or behaviours associated with a diagnosis of ASD and consequently place these children at high risk for victimization. Several studies of bullying and ASD have indicated that social exclusion, peer marginalization, and number of friendships are all related to rates of victimization within the ASD population (Cappadocia et al. 2012; Carter 2009; Kowalski and Fedina 2011; Little 2002; Sofronoff et al. 2011; Symes and Humphrey 2010; Twyman et al. 2010; Wainscot et al. 2008). In addition, aggressive children tend to victimize peers who exhibit mental health vulnerabilities (e.g., internalizing problems; Fekkes et al. 2006). The behavioural, sensory, and communication differences that characterize ASD may play a role in the marginalization and victimization of children with ASD among their peers, as aggressive children who bully others may target them for being different. A critical direction for further research is to identify the specific deficits in social behaviour and cognition that may put those with ASD at an increased risk for victimization and bullying. Social naivety, characterized by vulnerability to deception and common among children with ASD, has been identified as a strong predictor of victimization among children in this population (Sofronoff et al. 2011). Van Roekel et al. (2010) found that errors in social perception with respect to perceiving the presence of bullying were related to rates of both bullying perpetration and victimization in adolescents with ASD. These studies help to clarify the role that specific social differences play regarding the increased rates of bullying among those with ASD, which may prove critical in the development and modification of intervention strategies that are individualized to those with ASD.

Several characteristics of individuals with ASD likely affect their involvement in bullying. For example, some children with ASD may be able to compensate somewhat for their social skills deficits and lack of automaticity regarding social cognition skills by applying their general intellectual abilities to social situations, which may prove effective in most social situations. While a typically developing student may automatically process social cues without actively considering them, a child with ASD may have to intentionally think through social situations in order to understand them and generate ideas about solutions, which would make higher cognitive processing skills an advantage in social situations. Those with more intact communication skills are more likely to be able to navigate social situations. Individuals with better self-regulation abilities, less obvious behavioural characteristics, or more socially acceptable topics of perseverative interest (e.g., music or movies) may also be less vulnerable. Having positive relationships with typically developing siblings may further facilitate social acceptance indirectly, by providing opportunities to practice social skills, and possibly through association with the sibling at school and on the playground if that is the nature of the relationship. Based on the risk and protective factors discussed throughout this paper, we speculate that environmental factors that merit consideration for reducing risk of victimization may include placement in mainstream versus specialized school programs, the implementation of tolerance or bullying training programs in the school, individual participation in social skills training, involvement in mainstream recreational programming, and parent support.

A better understanding of the specific risk and protective factors that impact bullying involvement represents a critical first step in developing interventions that are targeted for people with ASD to supplement more broad school-wide intervention programs. It is critical to broadly target the school environment in promoting tolerance and acceptance of differences, and to encourage and support students in taking action when they witness bullying. It is equally important that teachers and other school staff receive training regarding the unique needs of those with ASD and how best to support these students. Teachers can help support those with ASD who are neglected by peers because they elect not to attempt engaging in social interactions. For students with ASD who are actively trying to participate in social interactions, teachers may be able to construct and facilitate positive social interactions that are less likely to result in peer rejection (see Cappadocia et al. 2012).

An intervention strategy that approaches bullying problems at multiple levels (i.e., individual, peer, school, community) is required to foster healthy social relationships within the ASD population. There have been two recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the effectiveness of school-based bullying intervention programs across several countries. The first included the 30 largest and highest quality controlled program evaluations to date (Farrington and Tttofi 2009). The second represents the most comprehensive review to date, including all program evaluations that involved a control group, 53 in total (Ttofi and Farrington 2011). Based on these meta-analyses, it appears that school-based bullying interventions are effective. On average, perpetration and victimization decreased by 20–23 % among children and youths who received these interventions (Farrington and Ttofi 2009; Ttofi and Farrington 2011). In evaluating which particular elements of the intervention programs were associated with changes in bullying perpetration and victimization, several themes of note emerged that can inform prevention and intervention efforts within both general and ASD populations.

One important theme is school climate. At the classroom level, an anti-bullying environment and teacher training appear to be critical. Ttofi and Farington (2011) investigated links between program elements and effect sizes for bullying perpetration across studies in their meta-analysis. Through these analyses, they found that decreases in bullying perpetration among students were linked to teacher-related factors that included: improved playground supervision that focused on areas where bullying occurs, classroom management focused on detecting and addressing bullying, and implementation and enforcement of anti-bullying classroom rules.

Disciplinary methods are also associated with effective intervention (Ttofi and Farrington 2011). Restorative justice approaches seem most effective for addressing perpetration behaviours (Farrington and Ttofi 2009). These approaches focus on repairing unhealthy social relationships (e.g., those characterized by bullying) by bringing children and youth together to address the problem behaviours (Pepler 2006). Collaborative, school-wide initiatives for detecting and addressing bullying are important. Through investigating links between program elements and effect sizes for bullying perpetration and victimization across studies in their meta-analysis, Ttofi and Farington (2011) found that whole-school anti-bullying policies and school-wide bullying conferences for children were both associated with decreases in bullying perpetration among children (Ttofi and Farrington 2011). They also found that collaborations among professionals within schools (e.g., teachers and social workers) to address bullying were associated with decreases in victimization and perpetration.

These findings regarding a whole-school approach are not unexpected, given that bullying has recently been conceptualized as a relationship problem that requires relationship solutions among all youths and adults in the school environment (Pepler 2006). However, the reviewers reported conflicting findings regarding the impact of peer engagement (e.g., peer mediation or mentorship), a school climate element that is often incorporated into bullying interventions. In some cases it was linked to decreases in victimization, in others, increases (for details, see Farrington and Tttofi 2009; Ttofi and Farrington 2011).

These evidence-based school climate elements associated with effective bullying interventions have implications for future interventions in both general and ASD populations. It seems critical that interventions include teacher training regarding effective playground and classroom supervision to detect and address bullying as it occurs. Teachers who have received training tend to feel more confident about intervening during bullying episodes (Alsaker 2004). In addition, it appears that engaging the entire school environment in promoting positive relationships and reducing bullying is important, although it is unclear whether youths should be included in the program delivery. It is significant to note that most of these elements of school climate were related to decreases in perpetration, but not victimization, among children and youths. These findings indicate that a whole-school approach is not sufficient for addressing bullying in schools. It is likely also crucial to work individually with children who are involved in bullying perpetration and/or victimization. Through scaffolding, adults can support children who are involved in these negative peer dynamics to acquire and develop important social skills (e.g., adaptive emotional and behavioral regulation, effective social problem solving, assertive communication; Cummings et al. 2006).

Parent involvement is another important element in effective bullying intervention. Both meta-analyses indicated that educating parents about bullying and the associated intervention being implemented in their children’s schools is instrumental in addressing bullying among children. Through investigating links between program elements and effect sizes for bullying perpetration across studies in their meta-analysis, Ttofi and Farington (2011) found that parent training is linked to decreases in both perpetration and victimization. Therefore, it is suggested that future school-based bullying interventions in both general and ASD populations involve parents in the implementation of intervention efforts. Given that parents are critical role models and socialization agents among children and youths, it is important to provide parents with education regarding their role in detecting and addressing bullying. It is also important that parents support their children by helping them develop adaptive social skills and creating opportunities for positive social interactions with others. Recent research highlights the importance and effectiveness of parent-assisted social skill development among children with ASD in particular (Frankel et al. 2010; Laugeson et al. 2009).

A final important theme is related to intervention design and implementation. Both meta-analyses indicate that duration (number of days) and intensity (number of hours) of the intervention impacts program efficacy when investigating links between program elements and effect sizes for bullying perpetration and victimization (Farrington and Ttofi 2009; Ttofi and Farrington 2011). It appears prudent to implement intensive, long-term interventions to effectively reduce perpetration and victimization among youths. Given that practiced patterns of interpersonal relationship dynamics can become deeply entrenched over time, it is not surprising that it takes persistent efforts over a long period to shift a whole school environment into a new framework for promoting healthy relationships and addressing unhealthy relationships such as bullying (e.g., Hay et al. 2004).

Methodological Considerations

There are a number of methodological differences across studies, which limit the degree to which they can be compared. Many differences exist with respect to how researchers operationalize bullying and victimization. Measures of bullying experiences differ on many levels including definitions of bullying (if provided), wording and number of items used to index perpetration and/or victimization. The timeframe considered makes comparisons across studies challenging. The benefit of a shorter timeframe (e.g., past week) is that the data collected are more likely to be accurate as they are not as impacted by memory. However, longer terms (e.g., past year) are more likely to reveal consistent patterns in bullying involvement and are better able to address issues of chronicity.

The way in which bullying is conceptualized is an important methodological issue, particularly when considering perpetration among children with an ASD because some definitions of bullying require that the perpetrator intends to harm the other person. It is more difficult to determine whether there is intention to harm among individuals with ASD, given their characteristic impairments in theory of mind. For example, a student with ASD who publicly corrects a peer in class could be perceived as engaging in verbal bullying by others, however, they may not understand that the statement could be perceived as hurtful by the other student. Conversely, theory of mind deficits may also make it difficult for a child with ASD to differentiate between playful teasing amongst friends and hurtful teasing. Qualitative methods may be particularly useful in determining how respondents define and understand their own bullying perpetration and victimization experiences.

The use of multiple informants has provided insight into how different respondents perceive bullying. Although there are generally modest correlations across informants, some interesting differences have also emerged. For example, one study found that many parents were unsure about cyber bullying experiences among their children, but were fairly consistent with their children regarding reports of traditional forms of bullying (Kowalski and Fedina 2011). Teachers in special education settings tend to report more victimization than the students themselves (Van Roekel et al. 2010), which may indicate that the children do not always interpret social situations appropriately or that teachers interpret playful or neutral interactions as bullying. Determining the reliability of informants regarding bullying is a challenge within general and ASD populations alike. Parent-report can provide information that children may elect not to share with researchers, and provide insight into situations that the child may not be able to understand. The drawback to parent report is that it often indirect, requiring information from the child or the teacher on what is happening at school. Teacher-report provides direct information about the school setting and the target student’s experience with bullying relative to peers. Self-report provides important insight into more subtle forms of bullying that may not be noticed by teachers. Further, self-report may also capture incidences that have not been reported to parents or teachers. The primary limit of self-report is that children may elect not to share bullying experiences or they may have difficulty accurately interpreting social situations. This issue is particularly complicated and important to research within the ASD population because those with ASD may have even more difficulty recognizing when they have been victimized. Conversely, those with ASD are also more likely to misinterpret friendly joking and teasing as verbal bullying (Samson et al. 2011). As such, an important component of effective intervention should include supporting children with ASD in recognizing and reporting victimization.

In all research with children, particularly when samples include those with developmental disabilities, it is extremely important to consider the intellectual capacity and specific diagnostic information about respondents, especially when examining self-report, as there may be limits to their capacity to understand the questions. Most of the reviewed self-report studies required that the child have the capacity to read or understand questions pertaining to bullying, and most included children with at least average cognitive capacity (Kowalski and Fedina 2011; Rieffe et al. 2012; Shtayermman 2007; Van Roekel et al. 2010; Wainscot et al. 2008). Additionally, some of the self-report studies focused on Asperger syndrome (Kowalski and Fedina 2011; Shtayermman 2007), while others examined participants with ASD more generally (Humphrey and Symes, Rieffe et al. 2012; Twyman et al. 2010), or combined participants with Asperger syndrome with other diagnoses across the autism spectrum (Van Roekel et al. 2010; Wainscot et al. 2008). Few studies have examined bullying in children with ASD + intellectual disability. Exceptions were Rowley et al. (2012), who reported a mean IQ of 80 for their sample, with a standard deviation of 20, and Didden et al. (2009), where most of the sample had IQs below the average range.

Interpretation of self-report results would be greatly supplemented with more direct measures such as peer report, naturalistic observation, or video recordings of real interactions between children. To date, only one study exploring bullying in ASD has used sociometric data to validate perceived student experiences and no studies have used observational methods (Symes and Humphrey 2010). These direct methods will prove to be a critical next step in understanding bullying experiences in ASD and generalizing current findings to children with ASD and impaired cognitive or communication abilities.

Areas for Future Research

Bullying among children with ASD has only recently become a focus of research and there are many areas in need of future study. The role of inclusion status in victimization requires further examination for clarification. Rowley et al. (2012) found that those in specialized education programs had lower teacher-reported victimization rates than those in mainstream programs. Consistent with these results, the number of general education classes within which individuals were enrolled also predicted victimization in those with ASD (Sterzing et al. 2012). It may be that children with ASD tend not to receive sufficient support from school staff within mainstream school environments, but this variable has not yet been investigated. Furthermore, teachers in mainstream schools may be less likely to set up structured social encounters and other environmental supports to facilitate positive peer interactions and support students with ASD within the larger peer group. Mainstream schools may be less likely to focus on the implementation of programs aimed at tolerance and acceptance of those with special needs. Additionally, children with ASD who are high functioning and attending mainstream school may be more likely than their lower functioning peers to be exposed to and seek social opportunities with other children. In turn, this may increase the likelihood that they will experience rejection and be victimized by peers. Furthermore, the behavioural, sensory, and emotional differences that children with ASD exhibit may be more noticeable, and thus more likely to be targeted, in a mainstream school environment than in a setting where there is more diversity in abilities.

Preliminary research suggests elevated rates of bullying perpetration among individuals with ASD that, according to one study, may be moderated at least in part by the presence of ADHD (Didden et al. 2009; Rieffe et al. 2012; Rowley et al. 2012; Kowalski and Fedina 2011; Montes and Halterman 2007; Van Roekel et al. 2010; Zablotsky et al. 2013). A further area for research development is to examine longitudinal trends within the ASD population to determine age trends in bullying perpetration and victimization, and to help identify causal relationships between risk and protective factors and rates of bullying and victimization. This would serve to reduce cohort, cultural, or generational effects of cross-sectional designs. Longitudinal designs are valuable when examining risk and protective factors in ASD, in particular, given that autism and mental health symptomatology show variability over time. This line of research could be further developed by examining gender differences among children with ASD to see if they are similar to those found within the typical population.

The relationship between ASD symptom severity and involvement with bullying and victimization also requires further study. An interesting pattern has emerged within the literature suggesting that higher functioning individuals with ASD (i.e., lower levels of social impairment) exhibit higher rates of bullying and victimization (Rowley et al. 2012; Shtayermman 2007). Further research is needed to corroborate these findings and to elucidate possible underlying mechanisms.

It will be important to examine the relationship among mental health problems, bullying, and victimization within the ASD population. Mental health problems are known to be more prevalent within the ASD population, particularly among those with Asperger Syndrome relative to the general population (for a recent review, see Schroeder et al. 2011). Consistent with trends in the general population, studies reviewed in this paper indicate a relationship between internalizing problems and bullying perpetration and victimization (Cappadocia et al. 2012; Kowalski and Fedina 2011; Sofronoff et al. 2011; Zablotsky et al. 2013). One study did not identify a relationship between victimization and internalizing problems, possibly due to small sample size (n = 10; Shtayermman 2007). There was also no relationship found between cyber bullying and internalizing symptoms (Kowalski and Fedina 2011).

Victimization has also been associated with externalizing problems among those with ASD (Cappadocia et al. 2012; Sofronoff et al. 2011). Interestingly, Rieffe et al. (2012) found that while anger was a significant correlate of perpetration in both ASD and typically developing samples, anger was also correlated with victimization among those with ASD only. Researchers should continue to explore the similarities and differences between those with ASD and typically developing peers regarding the relationship between mental health and bullying involvement. Longitudinal methods would be particularly useful in helping to determine the direction of causality between bullying involvement and mental health problems in ASD. Finally, it would be important to determine the internal, environmental, and relationship factors that lead to resilience in children and teens with ASD who are not disproportionately involved in bullying.

References

Alsaker, F. D. (2004). Bernese program against victimization in kindergarten and elementary schools. In P. K. Smith, D. Pepler & K. Rigby (Eds.), Bullying in schools: How successful can interventions be? (pp. 289–306). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Alsaker, F. D., & Valkamover, S. (2001). Early diagnosis and prevention of victimization in kindergarten. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 175–195). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Arora, T. (1991). The use of victim support groups. In P. K. Smith & D. A. Thompson (Eds.), Practical approaches to bullying. London: David Fulton.

Arora, C., & Thompson, D. (1987). Defining bullying for the secondary school. Educational and Child Psychology, 4, 110–120.

Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition, 21, 37–46.

Bauminger, N., & Kasari, C. (2000). Loneliness and friendship in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development, 71, 447–456.

Boivin, M., Hymel, S., & Bukowski, W. M. (1995). The roles of social withdrawal, peer rejection, and victimization by peers in predicting loneliness and depressed mood in childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 765–785.

Boulton, (1999). Concurrent and longitudinal relations between children’s playground behavior and social preference, victimization, and bullying. Child Development, 70(4), 944–954.

Boulton, M. J., & Underwood, K. (1992). Bully/victim problems among middle school children. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 62, 73–87.

Cappadocia, M. C., Weiss, J. A., & Pepler, D. (2012). Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal on Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(2), 266–277.

Carter, S. (2009). Bullying of students with Asperger syndrome. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 32, 145–154.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2003). National survey of children’s health. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov.ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm#2003nsch.

Chamberlain, B., Kasari, C., & Rotheram-Fuller, E. (2007). Involvement or isolation? The social networks of children with autism in regular classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 230–242.

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25(2), 65–83.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1996). Children’s treatment by peers. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 367–380.

Cummings, J. G., Pepler, P., Mishna, F., & Craig, W. (2006). Bulling and victimization among students with exceptionalities. Exceptionality Education, 16, 193–222.

Davis, S., Howell, P., & Cooke, F. (2002). Sociodynamic relationships between children who stutter and their non-stuttering classmates. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(7), 939–947.

DeRosier, M. E., Kupersmidt, J. B., & Patterson, C. J. (1994). Children’s academic and behavioral adjustment as a function of the chronicity and proximity of peer rejection. Child Development, 65, 1799–1813.

Didden, R., Scholte, R. H., Korzilius, H., De Moor, J. M. H., Vermeulen, A., O’Reilly, M. O., et al. (2009). Cyber bullying among students with intellectual and developmental disability in special education settings. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 12(3), 146–151.

Dunn, W., Saiter, J., & Rinner, L. (2002). Asperger syndrome and sensory processing: A conceptual model and guidance for intervention planning. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17(3), 172–185.

Estell, D. B., Farmer, T. W., Irvin, M. J., Crowther, A., Akos, P., Boudah, D. J., et al. (2009). Students with exceptionalities and the peer group context of bullying and victimization in late elementary school. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18(2), 136–150.

Farrington, D. P., & Tttofi, M. M. (2009). How to reduce school bullying. Victims and Offenders, 4, 321–326.

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I., Fredriks, A. M., Vogels, T., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2006). Do bullied children get ill, or do ill children get bullied? A prospective cohort study on the relationship between bullying and health-related symptoms. Pediatrics, 117, 1568–1574.

Forero, R., McLellan, L., Rissel, C., & Bauman, A. (1999). Bullying behaviour and psychosocial health among school students in New South Wales, Australia: A cross-sectional survey. British Medical Journal, 319, 344–348.

Frankel, F., Myatt, R., Whitham, C., Gorospe, C., & Laugeson, E. A. (2010). A controlled study of parent-assisted children’s friendship training with children having autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 827–842.

Gazelle, H., & Ladd, G. W. (2003). Anxious solitude and peer exclusion: A diathesis-stress model of internalizing trajectories in childhood. Child Development, 74(1), 257–278.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586.

Gray, C. (2004). Gray’s guide to bullying parts I–III. Jenison Autism Journal, 16(1), 2–19.

Hamby, S. L., & Finkelhor, D. (1999). The comprehensive juvenile victimization questionnaire. Paper presented at the 6th International Family Violence Research Conference, Durham, NH, July 1999.

Hanish, L. D., & Guerra, N. G. (2002). A longitudinal analysis of patterns of adjustment following peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology, 14(1), 69–89.

Haq, I., & Le Couteur, A. (2004). Autism spectrum disorder. Medicine, 32, 61–63.

Hay, D. F., Payne, A., & Chadwick, A. (2004). Peer relations in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(1), 84–108.

Haynie, D. L., Nansel, T., Eitel, P., Crump, A. D., Saylor, K., et al. (2001). Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups of at risk youths. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 21(1), 29–49.

Hodges, E. V. E., & Perry, D. G. (1999). Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(4), 677–685.

Humphrey, N., & Symes, W. (2010). Responses to bullying and use of social support among pupils with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) in mainstream schools: A qualitative study. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 10, 82–90.

Ivarsson, T., Broberg, A. G., Arvidsson, T., & Gillberg, C. (2005). Bullying in adolescence: Psychiatric problems in victims and bullies as measured by the Youth Self Report (YSR) and the Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 59, 365–373.

Kaltiala-Heino, R., Rimpela, M., Marttunen, M., Rimpela, A., & Rantanen, P. (1999). Bullying, depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents: School survey. British Medical Journal, 319, 348–356.

Kaltiala-Heino, R., Rimpela, M., Rantanen, P., & Rimpela, A. (2000). Bullying at school—an indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 661–674.

Kochenderfer, B. J., & Ladd, G. W. (1996). Peer victimization: Cause or consequence of school maladjustment. Child Development, 67(4), 1305.

Kowalski, R. M., & Fedina, C. (2011). Cyber bullying in ADHD and Asperger syndrome populations. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 1201–1208.

Kowalski, R. M., & Limber, S. (2007). Electronic bullying among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, S22–S30.

Kumpulainen, K., Räsänen, E., & Puura, K. (2001). Psychiatric disorders and the use of mental health services among children involved in bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 27, 102–110.

Laugeson, E. A., Mogil, C. E., Dillon, A. R., & Frankel, F. (2009). Parent-assisted social skills training to improve friendships in teens with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 596–606.

Little, L. (2002). Middle-class mothers’ perceptions of peer and sibling victimization among children with Asperger’s syndrome and nonverbal learning disorders. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 25, 43–57.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C., et al. (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 205–223.

Mahady Wilton, M., Craig, W. M., & Pepler, D. J. (2000). Emotional regulation and display in classroom bullying: Characteristic expressions of affect, coping styles and relevant contextual factors. Social Development, 9, 226–245.

Martlew, M., & Hodson, J. (1991). Children with mild learning difficulties in an integrated and in a special school: Comparisons of behaviour, teasing, and teachers’ attitudes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 61, 355–372.

Mishna, F. (2004). Learning disabilities and bullying: Double jeopardy. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 4, 336–347.

Molcho, M., Craig, W., Due, P., Pickett, W., Harel-Fisch, Y., Overpeck, M., et al. (2009). Cross-national time trends in bullying behaviour 1994–2006: Findings from Europe and North America. International Journal of Public Health, 54, 225–234.

Montes, G., & Halterman, J. S. (2007). Bullying among children with autism and the influence of comorbidity with ADHD: A population-based study. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 7(3), 253–257.

Myklebust, J. O. (2002). Inclusion or exclusion? Transitions among special needs students in upper secondary education in Norway. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 17(3), 251–263.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M. D., Haynie, D. L., Ruan, W. J., & Scheidt, P. C. (2003). Relationships between bullying and violence among US youth. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 157, 348–353.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M. D., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285, 2094–2100.

Norwich, B., & Kelly, N. (2004). Pupils’ views on inclusion: Moderate learning difficulties and bullying in mainstream and special schools. British Educational Research Journal, 30(1), 43–65.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Oxford: Blackwell.

Olweus, D. (1996/2004). The revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Bergen, Norway: Research Centre for Health Promotion (HEMIL), University of Bergen, N-5015.

Olweus, D. (1997). Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 12, 495–510.

Pepler, D. J. (2006). Bullying interventions: A binocular perspective. Journal of Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 15, 16–20.

Pepler, D. J., Craig, W., & O’Connell, P. (1999). Understanding bullying from a dynamic systems perspective. In A. Slater & D. Muir (Eds.), Developmental psychology: An advanced reader. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Pepler, D., Jiang, D., Craig, W., & Connolly, J. (2008). Developmental trajectories of bullying and associated factors. Child Development, 79, 325–338.

Perry, D. G., Kusel, S. J., & Perry, L. C. (1998). Victims of peer aggression. Developmental Psychology, 24, 807–814.

PREVNet Assessment Working Group. (2008). Promoting relationships and eliminating violence network assessment tool-parent and child versions. Kingston: PREVNet.

Reynolds, W. M. (1991). Psychometric characteristics of the Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire in college students. Journal of Personality Assessment, 56, 289–307.

Reynolds, W. M. (2003). Reynolds bully-victimization scales for schools. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Rieffe, C., Camodeca, M., Pouw, L. B. C., Lange, A. M. C., & Stockmann, L. (2012). Don’t anger me! Bullying, victimization, and emotion dysregulation in young adolescents with ASD. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9, 351–370.

Rigby, K., & Slee, P. T. (1993). The Peer Relations Questionnaire (PRQ). Adelaide: University of South Australia.

Rose, C. A., Espelage, D. L., & Monda-Amaya, L. E. (2009). Bullying and victimisation rates among students in general and special education: A comparative analysis. Educational Psychology, 29(7), 761–776.

Rose, C. A., Monda-Amaya, L. E., & Espelage, D. L. (2011). Bullying perpetration and victimization in special education: A review of the literature. Remedial and Special Education, 32, 114–130.

Rowley, E., Chandler, S., Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Loucas, T., et al. (2012). The experience of friendship, victimization, and bullying in children with an autism spectrum disorder: Associations with child characteristics and school placement. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 1126–1134.

Samson, A. C., Huber, O., & Ruch, W. (2011). Teasing, ridiculing, and the relation to the fear of being laughed at in individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 41, 475–483.

Saylor, C. F., & Leach, J. B. (2009). Perceived bullying and social support in students accessing special inclusion programming. Journal on Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 21, 69–80.

Schroeder, J. H., Weiss, J. A., & Bebko, J. M. (2011). CBCL profiles of children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome: A review and pilot study. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 17(1), 26–37.

Schwartz, D., McFadyen-Ketchum, S., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1999). Early behavior problems as a predictor of later peer group victimization: Moderators and mediators in the pathways of social risk. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(3), 191–201.

Sharp, S., & Cowie, H. (1994). Empowering students to take positive action against bullying. In P. K. Smith & S. Sharp (Eds.), School bullying: Insights and Perspectives (pp. 108–131). London: Routledge.

Shtayermman, O. (2007). Peer victimization in adolescents and young adults diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome: A link to depressive symptomatology, anxiety symptomatology, and suicidal ideation. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 30, 87–107.

Slaughter, V., Dennis, M. J., & Pritchard, M. (2002). Theory of mind and peer acceptance in preschool children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20(4), 545–564.

Sofronoff, K., Dark, E., & Stone, V. (2011). Social vulnerability and bullying in children and Asperger syndrome. Autism, 15, 355–372.

Sterzing, P. R., Shattuck, P. T., Narendorf, S. C., Wagner, M., & Cooper, B. P. (2012). Bullying involvement in autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence and correlates of bullying involvement among adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 166(11), 1058–1064.

Symes, W., & Humphrey, N. (2010). Peer-group indicators of social inclusion among pupils with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) in mainstream secondary schools: A comparative study. School Psychology International, 31(5), 478–494.

Ttofi, M., & Farrington, D. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7, 27–56.

Twyman, K. A., Saylor, C. F., Saia, D., Macias, M. M., Taylor, L. A., et al. (2010). Bullying and ostracism experiences in children with special health care needs. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 31, 1–8.

Van Cleave, J., & Davis, M. M. (2006). Bullying and peer victimization among children with special health care needs. Pediatrics, 118, 1212–1219.

van Roekel, E., Scholte, H. J., & Didden, R. (2010). Bullying among adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence and perception. Journal on Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 63–73.

Wainscot, J. J., Naylor, P., Sutcliffe, P., Tantam, D., & Williams, J. V. (2008). Relationships with peers and use of the school environment of mainstream secondary school pupils with Asperger syndrome (high-functioning autism): A case–control study. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 8(1), 25–38.

Wang, J., Iannotti, R. J., Luk, J. W., & Nansel, T. R. (2010). Co-occurrence of victimization from five subtypes of bullying: Physical, verbal, social exclusion, spreading rumors, and cyber. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35(10), 1103–1112.

Zablotsky, B., Bradshaw, C. P., Anderson, C., & Law, P. A. (2013). The association between bullying and the psychological functioning of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 34(1), 1–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schroeder, J.H., Cappadocia, M.C., Bebko, J.M. et al. Shedding Light on a Pervasive Problem: A Review of Research on Bullying Experiences Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 44, 1520–1534 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-2011-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-2011-8