Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine trends in incidence, treatment and survival of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients with synchronous metastases (Stage IV) in the Netherlands. This nationwide population-based study included 160,278 patients diagnosed with CRC between 1996 and 2011. We evaluated changes in stage distribution, location of synchronous metastases and treatment in four consecutive periods, using Chi square tests for trend. Median survival in months was determined, using Kaplan–Meier analysis. The proportion of Stage IV CRC patients (n = 33,421) increased from 19 % (1996–1999) to 23 % (2008–2011, p < 0.001). This was predominantly due to a major increase in the incidence of lung metastases (1.7–5.0 % of all CRC patients). During the study period, the primary tumor was resected less often in Stage IV patients (65–46 %) and the use of systemic treatment has increased (29–60 %). Also an increase in metastasectomy was found in patients with one metastatic site, especially in patients with liver-only disease (5–18 %, p < 0.001). Median survival of all Stage IV CRC patients increased from 7 to 12 months. Especially in patients with metastases confined to the liver or lungs this improvement in survival was apparent (9–16 and 12–24 months respectively, both p < 0.001). In the last two decades, more lung metastases were detected and an increasing proportion of Stage IV CRC patients was treated with systemic therapy and/or metastasectomy. Survival of patients has significantly improved. However, the prognosis of Stage IV patients becomes increasingly diverse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most frequently diagnosed cancer types in the Western world, and second leading cause of cancer-related death in The Netherlands [1]. Approximately 15–25 % of all CRC patients have distant metastases (TNM Stage IV) at the time of the primary diagnosis [2–4]. Although metastases are predominantly located in the liver, little is known about patterns of metastatic spread.

Curative treatment is possible when resection of the primary tumor is accompanied by resection of all metastases. About 20–30 % of patients with liver metastases would have potentially resectable disease [5]; however, observational studies have reported resection rates of liver metastases around 5–15 % [2, 6], and 5 years overall survival rates of curatively operated patients up to 50 % [7]. Although most Stage IV CRC patients present with liver metastases, also patients with a limited number of metastases (oligometastases) in the lungs [8] or peritoneum [9] can be treated with curative intent when all metastatic lesions are removed.

However, for patients with unresectable metastatic disease, best supportive care with or without palliative systemic therapy is the only option. In the past decades, randomized controlled trials have shown that palliative chemotherapy improves survival of CRC patients with metastatic disease, especially after the introduction of combination regimens of fluorouracil with oxaliplatin or irinotecan [10–12]. Further improvement of survival was obtained with the addition of targeted therapies [13]. The additional value of systemic treatment was also found in population-based studies [2–4].

Resection of the primary tumor is indicated in patients with curative treatment options, or in the palliative setting when the primary tumor becomes symptomatic. However, resection of an asymptomatic primary tumor is currently under debate [14, 15]. Whether discussion about resection of the primary tumor has influenced treatment patterns is largely unknown. In addition, little is known about treatment patterns according to metastatic sites.

The aim of this nationwide population-based study was to determine trends in incidence, metastatic spread, treatment and survival of CRC patients with synchronous metastases in the Netherlands.

Methods

Patients

Population-based data were selected from the nationwide Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR), which covers over 16.7 million inhabitants. In the NCR, data on all newly diagnosed malignancies in the Netherlands are registered. Main sources of notification are the automated pathology archive (PALGA) and the National Registry of Hospital Discharge Diagnoses. Following notification, specially trained registration clerks collect data on patient, tumor and treatment characteristics from the medical records in all hospitals. Completeness of the NCR is estimated to be at least 95 %. Topography and morphology were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) [16]. Stage of disease was defined according to the tumor–lymph node–metastasis (TNM) classification [17].

For this paper, all patients with colorectal carcinoma in the period 1996–2011 were selected. Patients with CRC diagnosed at autopsy or without histological confirmation were excluded. Tumor location was categorized as colon (including recto sigmoid: C18–19) or rectum (C20). Date of diagnosis was divided into four periods: 1996–1999, 2000–2003, 2004–2007, and 2008–2011.

Synchronous metastases were defined as metastases detected before the start of initial treatment and/or during surgical exploration. Data on the location of distant metastases at organ level (with a maximum of three sites) were registered in four out of nine NCR-regions in 1996–1999, increasing to national coverage from 2008 onwards. From each region, we have included those years with a (nearly) complete registration of location of distant metastases, resulting in 3.5 % missing locations of metastases of included Stage IV patients (0.7 % of included patients).

Treatment after diagnosis included the treatment modalities as mentioned in the treatment plan and provided to the patient. Treatment was categorized as resection of primary CRC tumor, metastasectomy (surgical resection of one or more metastatic sites) and systemic treatment (chemotherapy, targeted therapy).

Follow-up on vital status (deceased or alive) was obtained from the national Municipal Personal Records Database, which contains information on vital status of all Dutch inhabitants.

Statistical analysis

Chi square tests for trend were used to assess the trends in stage distribution in the consecutive periods, as well as trends in the location of distant metastases (denominator: CRC all stages) and trends in treatment of Stage IV CRC patients. Due to a change in the TNM-classification of lymph node metastases from 2003 onwards [17], sensitivity analyses were performed with all distant lymph node metastases categorized as non-distant (regional), showing similar trends over time.

Survival time was defined as the time from first histological diagnosis to death. Patients who were still alive at January 1st, 2014 were censored. In consecutive periods, median survival times with 95 % confidence intervals were computed of Stage IV CRC patients according to age and location of the primary tumor and locations of distant metastases, using Kaplan–Meier analyses. Differences in survival between subgroups were tested using the log rank test. All analyses were performed using STATA/SE (version 12.0; STATA Corp., College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Between 1996 and 2011, 160,278 new patients were diagnosed with CRC. The proportion of patients with synchronous metastases gradually increased from 19 % in 1996–1999 to 23 % in 2008–2011 (p < 0.001). Within this period, the proportion of patients with Stage II disease decreased (from 33 % to 28 %, p < 0.001). This pattern was found in both colon and rectal cancer patients, as shown in Fig. 1. Compared to Stage I–III CRC patients (n = 126,857), Stage IV CRC patients (n = 33,421) were younger (median age 69 vs. 71 years, p < 0.001), more often male (55 vs. 53 %, p < 0.001), and the primary tumour was more often localized in the colon (76 vs. 71 %, p < 0.001). Over time, median age of Stage IV patients remained stable (69 years), the primary tumor more often was found in the rectum (22–26 %, p < 0.001), the proportion of patients with a T3 or T4 primary tumor decreased (73–67 %, p < 0.001) and patients more often were diagnosed with positive lymph nodes (51–60 %, p < 0.001). Seventy-two percent of all CRC patients were included in analyses of metastatic spread (Table 1), patient and tumor characteristics of Stage IV patients in this subgroup did not differ from those of all Stage IV patients (data not shown).

Synchronous metastases

The most common site of distant metastases in CRC patients was the liver, followed by the peritoneum and the lungs (Table 1). Over time, an increasing percentage of patients was diagnosed with metastases in more than one organ (from 3.6 % of all patients in 1996–1999 to 8.0 % in 2008–2011, p < 0.001). The proportion of patients with liver metastases increased from 14 % to 17 % (p < 0.001) and with peritoneal carcinomatosis from 3.7 to 4.7 % (p < 0.001), while the proportion of patients with lung metastases more than doubled, from 1.7 % to 5.0 % (p < 0.001). The largest increase was seen especially in patients with lung metastases only (0.4–1.1 %) and in patients with liver and lungs affected (from 1.1 to 3.4 %).

Compared to rectal cancer patients, colon cancer patients were more often diagnosed with peritoneal metastases (4.5 vs. 1.7 % in 1996–1999 and 6.0 vs. 1.7 % in 2008–2011, both p < 0.001) and less often with lung metastases (1.4 vs. 2.5 % in 1996–1999 and 4.4 vs. 6.3 % in 2008–2011, both p < 0.001).

Treatment

Between 1996 and 2011 the percentage of Stage IV CRC patients undergoing metastasectomy increased from 4 % (1996–1999) to 12 % (2009–2011, p < 0.001), with higher median age in the last period (64 vs. 62 years). Analyzed separately, this increased metastasectomy rate was only found in patients with metastatic disease isolated to one organ (Table 2). The most markedly increase was found in patients with isolated liver metastases (5–18 %, p < 0.001). We also found an increase in the use of systemic treatment for Stage IV patients (29–60 %, p < 0.001), which was combined with targeted therapies in 28 % of patients in 2008–2011. Especially in patients with isolated liver metastases and in patients with multiple organs affected, the use of systemic treatment was high. The median age of patients receiving systemic treatment gradually increased over time (from 61 to 65 years). The proportion of patients undergoing resection of the primary tumor decreased over time from 65 to 46 % (p < 0.001). The largest decrease was seen in patients with multiple-organ metastases, followed by patients with metastases confined to the liver. Median age of patients undergoing resection of their primary tumor remained stable (68 years).

In the last period (2008–2011), 8 % of patients received a combination of above mentioned treatment modalities (systemic treatment, resection primary tumor, metastasectomy) and 21 % of patients had both systemic treatment and resection of the primary tumor, compared to 1 and 19 % respectively in the first period (p < 0.001). Over time, an increasing proportion of these patients have received systemic treatment prior to resection of the primary tumor (from 3 % in 1996–1999 to 21 % in 2008–2011, p < 0.001).

Survival

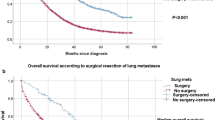

As shown in Table 3, median survival of Stage IV CRC patients has gradually increased from 7.2 months (95 % Confidence Interval [CI] 6.9–7.5) to 12.0 months (95 %CI 11.6–12.4) (Fig. 2a). Compared to elderly patients and colon cancer patients, patients younger than 75 years and rectal cancer patients showed a higher median survival and a larger progress over time. Improvement of survival was largest in patients with metastatic disease confined to the liver (8.8–15.6 months) or the lungs (11.7–24.0 months). Patients with bone or brain metastases had the worst median survival, and showed little or no progress over time.

Crude survival of CRC patients diagnosed with synchronous distant metastases in the period 1996–2011 in the Netherlands, by period of diagnosis of CRC: a all patients (log rank test p < 0.001), b patients treated with metastasectomy (log rank test p < 0.001), c patients receiving systemic treatment without metastasectomy (log rank test p < 0.001) and d patients receiving supportive care (no metastasectomy, no systemic treatment) (log rank test p < 0.001)

Survival was highest in patients who underwent metastasectomy (with or without other treatments). These patients also showed the largest improvement in survival, from median 25.0 months (95 %CI 22.1–31.8, 1996–1999) to 46.2 months (95 %CI 40.5–52.4, 2008–2011, Fig. 2b). In patients who received systemic treatment without undergoing metastasectomy, median survival increased from 12.1 months (95 %CI 11.5–12.7) to 15.3 months (95 %CI 14.8–15.8, Fig. 2c), while survival of patients receiving neither metastasectomy nor systemic treatment (best supportive care) decreased from 5.1 months (95 %CI 4.9–5.4) to 3.4 months (95 %CI 3.1–3.6, Fig. 2d). Furthermore, patients with lung-only metastases who underwent metastasectomy (median 56.1 months [95 %CI 31.1–90.3], n = 77) showed a similar median survival compared to patients who underwent resection of liver-only metastases (median 51.4 months [95 %CI 48.1–56.8], n = 1422, period 1996–2011, p = 0.69).

Discussion

This nationwide population-based study in the Netherlands showed that the proportion of CRC patients diagnosed with Stage IV disease increased between 1996 and 2011. The largest increase was found in the incidence of lung metastases only and combined lung and liver metastases. In Stage IV patients, a decrease was found in resection of the primary tumor, while the use of systemic treatment increased, as well as the use of metastasectomy. The highest rate of metastasectomy and the largest increase over time were found in patients with isolated liver metastases. Survival of Stage IV CRC patients has gradually increased, especially in patients with isolated liver or lung metastases, and in patients who underwent surgical resection of their metastases.

The increasing proportions of Stage IV CRC patients are in line with earlier reports from the Netherlands [2–4]. In the absence of a national screening program, the shift in stage distribution can be attributed to more accurate staging, due to improved pathological detection of lymph node involvement in the resection specimen [18], and improved detection of metastatic disease. An increased use and improved quality of computed tomography (CT) of the chest and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver has potentially led to an increased detection rate for lung and liver metastases [19, 20].

The present study showed that the incidence of synchronous lung metastases more than doubled,, which is in line with a French population-based study [21], and the incidence of lung metastases became slightly higher than that of peritoneal metastases. In earlier years, patients with small lung-only metastases might have been diagnosed as non-metastatic CRC. The improved detection of lung metastases also explains the increase of patients with both liver and lung metastases. Our data suggest that improvements in detecting lung and other non-liver metastases have surpassed an improvement in the detection of liver metastases, since a ‘decrease’ in the proportion of patients with liver metastases was found within the subset of patients with Stage IV disease (from 80 to 76 %). Considering all CRC patients (Stage I–IV), however, the incidence of liver metastases has increased from 14 to 17 %. As the NCR has no data available on the number of detected metastases per organ, it is possible that the absolute number of diagnosed liver metastases per patient did increase. The minor changes in bone, brain and other more atypical metastases probably reflect the fact that diagnostic imaging for these sites is not performed routinely. However, when curative treatment is considered, positron emission tomography (PET) scanning has additional value in the detection of extra-hepatic metastases [22].

Consistent with several other studies [2–4, 7, 23], an increased use of systemic treatment in Stage IV CRC patients was found. Simultaneously, the percentage of patients undergoing resection of the primary tumor decreased over time, especially in patients with multiple organ metastases. This decrease may reflect the recent debate about the added value of palliative resection of the primary tumor [15, 24–26]. However, it also may reflect an increased preference for chemotherapy as the treatment of first choice [27, 28], as we found in this study.

The present study showed an increase in metastatic surgery for patients with metastatic disease confined to one site. It is plausible that the majority of these patients were treated with curative intent. The largest increase was found in patients with liver-only metastases, which is potentially due to the introduction of new treatment possibilities and improved surgical techniques [7]. These improvements, together with the increasing efficacy of systemic therapy to make secondary resection possible, are expected to further increase the proportion of patients undergoing liver surgery. Therefore, close collaboration with centers of expertise in liver surgery is essential to select patients eligible for treatment with curative intent [29]. Although less pronounced, we also observed an increase in surgical treatment of metastases in patients with lung or other single organ metastases. The proportion of patients with advanced metastatic disease undergoing metastasectomy did not change over time. However, there is some evidence that curative resection is possible in selected patients with multiple organ metastases [9, 30, 31].

In the Netherlands, median overall survival in the total group of CRC patients diagnosed with synchronous Stage IV disease increased from 7.2 months in 1996–1999 to 12.0 months in 2008–2011. Consistent with reports from other countries [23, 32], the largest improvement in survival was seen in patients below the age of 75. These patients are more often eligible for surgical and systemic treatment, and they can better withstand the complications and side effects of treatment. However, median age of systemic treated patients increased over time and median survival of elderly patients improved especially in recent periods. Therefore, increasing numbers of elderly patients receiving curative or palliative cancer treatments may have contributed to a slowed survival improvement in the last period. The increasing survival gap between patients with colon cancer and patients with rectal cancer is remarkable. This survival gap may to some extend be explained by differences in patterns of metastatic spread. Peritoneal metastases are more frequently found in colon cancer patients, whereas lung metastases are more common in rectal cancer patients [33]. Survival is found to be less favorable in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis than in patients with lung metastasis [34, 35], as was also confirmed in this study.

The survival benefit for patients with single-organ metastasis can easily be explained, as they will more often be eligible for curative surgery than patients with multiple organs affected. In patients who received palliative systemic treatment, survival was lower than reported in randomized trials [10–12], which is partly because the general population encompass elderly and frail patients who are usually not included in those trials. This is reflected by the fact that only 28 % of the patients in this population based study received modern, expensive, systemic targeted treatment which might also explain the lower overall survival. A recent study showed that patients with Stage IV CRC not fulfilling eligible criteria for the original trial had a worse outcome while eligible non-trial patients showed a similar outcome compared to trial participants [36].

The remarkable improvement in survival for patients with lung metastases, especially patients with lung-only metastases, can partly be contributed to improvements in systemic therapy and surgical intervention. However, to some extent it will also reflect earlier diagnosis as a result of improved imaging techniques [19, 21, 37]. Probably, this phenomenon has influenced other survival outcomes as well. With regard to survival of CRC patients who underwent metastasectomy of lung metastases, results in this study are in line with a recent review of 25 retrospective series reporting a median survival between 18.5 and 72 months [8].

A limitation in this study is the amount of lacking data on location of metastasis for patients diagnosed between 1996 and 2007. With careful selection of included data, missing values were limited to a minimum without compromising representativeness. Furthermore, in the literature several definitions are used for distinguishing synchronous and metachronous metastases. Because the NCR does not provide information on the date of diagnosis of distant metastases, we cannot select distant metastases that were diagnosed within a predefined period of date of diagnosis of the primary tumor (e.g. 3, 6 or 12 months) to analyze possible differences in the incidence of distant metastases.

In conclusion, an increase in the proportion of Stage IV CRC patients was observed over the last two decades. This increase can mainly be explained by an improved detection of non-liver metastases, especially lung metastases. In upcoming years, further increase of survival is expected, when more patients will undergo metastatic surgery and the efficacy of systemic treatment increases further by the developments in personalized medicine. Optimizing the use of personalized medicines justifies an extensive tracking system of treatment and treatment results. However, treatment and survival patterns may further diverge according to metastatic spread.

References

Netherlands Cancer R. Dutch Cancer Figures. 2013

van der Pool AE, Damhuis RA, Ijzermans JN et al (2012) Trends in incidence, treatment and survival of patients with stage IV colorectal cancer: a population-based series. Colorectal Dis 14:56–61

Elferink MA, van Steenbergen LN, Krijnen P et al (2010) Marked improvements in survival of patients with rectal cancer in the Netherlands following changes in therapy, 1989–2006. Eur J Cancer 46:1421–1429 (Oxford, England : 1990)

van Steenbergen LN, Elferink MA, Krijnen P et al (2010) Improved survival of colon cancer due to improved treatment and detection: a nationwide population-based study in The Netherlands 1989–2006. Ann Oncol 21:2206–2212

Kanas GP, Taylor A, Primrose JN et al (2012) Survival after liver resection in metastatic colorectal cancer: review and meta-analysis of prognostic factors. Clin Epidemiol 4:283–301

Hackl C, Gerken M, Loss M et al (2011) A population-based analysis on the rate and surgical management of colorectal liver metastases in southern Germany. Int J Colorectal Dis 26:1475–1481

Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ et al (2009) Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 27:3677–3683

Gonzalez M, Poncet A, Combescure C et al (2013) Risk factors for survival after lung metastasectomy in colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 20:572–579

de Cuba EM, Kwakman R, Knol DL et al (2013) Cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for peritoneal metastases combined with curative treatment of colorectal liver metastases: systematic review of all literature and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Treat Rev 39:321–327

de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M et al (2000) Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 18:2938–2947

Saltz LB, Cox JV, Blanke C et al (2000) Irinotecan plus fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. Irinotecan Study Group. N Engl J Med 343:905–914

Koopman M, Antonini NF, Douma J et al (2007) Sequential versus combination chemotherapy with capecitabine, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer (CAIRO): a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet 370:135–142

Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W et al (2004) Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 350:2335–2342

Cirocchi R, Trastulli S, Abraha I et al (2012) Non-resection versus resection for an asymptomatic primary tumour in patients with unresectable stage IV colorectal cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 8:CD008997

Verhoef C, de Wilt JH, Burger JW et al (2011) Surgery of the primary in stage IV colorectal cancer with unresectable metastases. Eur J Cancer 47(Suppl 3):S61–S66 (Oxford, England : 1990)

Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A et al (2000) International classification of diseases for oncology (ICD-O). World Health Organization, Geneva

Wittekind C, Greene FL, Hutter RVP et al (2004) TNM atlas. Springer, Berlin

Nagtegaal ID, Tot T, Jayne DG et al (2011) Lymph nodes, tumor deposits, and TNM: are we getting better? J Clin Oncol 29:2487–2492

Parnaby CN, Bailey W, Balasingam A et al (2012) Pulmonary staging in colorectal cancer: a review. Colorectal Dis 14:660–670

Bipat S, Niekel MC, Comans EF et al (2012) Imaging modalities for the staging of patients with colorectal cancer. Neth J Med 70:26–34

Mitry E, Guiu B, Cosconea S et al (2010) Epidemiology, management and prognosis of colorectal cancer with lung metastases: a 30-year population-based study. Gut 59:1383–1388

Wiering B, Vogel WV, Ruers TJ et al (2008) Controversies in the management of colorectal liver metastases: role of PET and PET/CT. Dig Surg 25:413–420

Mitry E, Rollot F, Jooste V et al (2013) Improvement in survival of metastatic colorectal cancer: are the benefits of clinical trials reproduced in population-based studies? Eur J Cancer 49:2919–2925 (Oxford, England : 1990)

Damjanov N, Weiss J, Haller DG (2009) Resection of the primary colorectal cancer is not necessary in nonobstructed patients with metastatic disease. Oncologist 14:963–969

Benoist S, Pautrat K, Mitry E et al (2005) Treatment strategy for patients with colorectal cancer and synchronous irresectable liver metastases. Br J Surg 92:1155–1160

Hu CY, Bailey CE, You YN et al (2015) Time trend analysis of primary tumor resection for stage iv colorectal cancer: less surgery, improved survival. JAMA Surg 150:245–251

Scheer MG, Sloots CE, van der Wilt GJ et al (2008) Management of patients with asymptomatic colorectal cancer and synchronous irresectable metastases. Ann Oncol 19:1829–1835

Vargas GM, Sheffield KM, Parmar AD et al (2014) Trends in treatment and survival in older patients presenting with stage IV colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 18:369–377

Jones RP, Vauthey JN, Adam R et al (2012) Effect of specialist decision-making on treatment strategies for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg 99:1263–1269

Hattori N, Kanemitsu Y, Komori K et al (2013) Outcomes after hepatic and pulmonary metastasectomies compared with pulmonary metastasectomy alone in patients with colorectal cancer metastasis to liver and lungs. World J Surg 37:1315–1321

Chua TC, Saxena A, Liauw W et al (2012) Hepatectomy and resection of concomitant extrahepatic disease for colorectal liver metastases–a systematic review. Eur J Cancer 48:1757–1765 (Oxford, England : 1990)

Sorbye H, Cvancarova M, Qvortrup C et al (2013) Age-dependent improvement in median and long-term survival in unselected population-based Nordic registries of patients with synchronous metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 24:2354–2360

Kornmann M, Staib L, Wiegel T et al (2013) Long-term results of 2 adjuvant trials reveal differences in chemosensitivity and the pattern of metastases between colon cancer and rectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 12:54–61

Khattak MA, Martin HL, Beeke C et al (2012) Survival differences in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer and with single site metastatic disease at initial presentation: results from South Australian clinical registry for advanced colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 11:247–254

Lemmens VE, Klaver YL, Verwaal VJ et al (2011) Predictors and survival of synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: a population-based study. Int J Cancer 128:2717–2725

Mol L, Koopman M, van Gils CW et al (2013) Comparison of treatment outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer patients included in a clinical trial versus daily practice in The Netherlands. Acta Oncol 52:950–955

Downs-Canner S, Bahar R, Reddy SK et al (2012) Indeterminate pulmonary nodules represent lung metastases in a significant portion of patients undergoing liver resection for malignancy. J Gastrointest Surg 16:2256–2259

Conflict of interest

The submitted material has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. We declare there are no conflicts of interest. The manuscript has been seen and approved by all authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van der Geest, L.G.M., Lam-Boer, J., Koopman, M. et al. Nationwide trends in incidence, treatment and survival of colorectal cancer patients with synchronous metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis 32, 457–465 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-015-9719-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-015-9719-0