Abstract

Workplace incivility is a current challenge in organizations, including smaller firms, as is the development of programs that enhance employees’ treatment of coworkers and ethical decision making. Ethics programs in particular might attenuate tendencies toward interpersonal misconduct, which can harm ethical reasoning. Consequently, this study evaluated the relationships among the presence of ethics codes and employees’ locus of control, social aversion/malevolence, and ethical judgments of incivility using information secured from a sample of businesspersons employed in smaller organizations (N = 189). Results indicated that ethics code presence was associated with a more internal locus of control and stronger ethical judgment of workplace incivility. Social aversion/malevolence was negatively related to ethical judgment, and internal locus of control was positively related to ethical judgment. Smaller firms should develop ethics codes to manage individuals’ perceptions of control, thus encouraging enhanced ethical reasoning in situations that involve the mistreatment of coworkers; they should also monitor counterproductive tendencies that harm such reasoning and precipitate incivility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Employees’ capacity to make ethical decisions is an important topic in the study of organizations (e.g., Craft 2013; Loe et al. 2000; O’Fallon and Butterfield 2005; Treviño 1986; Treviño and Nelson 2011). While much of this research has focused on ethical reasoning in larger organizations, comparatively fewer studies investigate the contextual conditions and individual characteristics that influence how employees in smaller organizations, and in some cases entrepreneurs, react to ethical problems. For instance, Harris et al. (2009) identified entrepreneurship and ethical decision making as a vital theme of research, but this research stream is typically focused on the entrepreneurs themselves, rather than on the employees of smaller/entrepreneurial firms. Prior research (e.g., Longenecker et al. 1989, 2006) has “…focused on ethical decision making by entrepreneurs and highlighted how entrepreneurs and small business owners vary in their sensitivity to moral/ethical issues and overall moral awareness (e.g., Dawson et al. 2002)” (Khan et al. 2013, pp. 637–638), moral awareness and self-regulation (Bryant 2009), expression of skills tied to moral reasoning (Teal and Carroll 1999), and questionable behaviors (Khan et al. 2013). Longenecker et al. (2006) found evidence that, compared to their counterparts in larger firms, owners/managers of smaller organizations reacted less ethically to ethics situations at one point of time in the 1990s, but found no significant differences between these individuals in two other years. While certainly insightful, such work does not address how all individuals working for smaller firms, not just owners and operators, make ethical decisions.

Related and important to such research is the prevailing idea that both contextual and individual factors influence ethical reasoning and behavior (e.g., Treviño 1986; Treviño and Youngblood 1990), an established paradigm embedded in many ethical decision-making models emphasizing the interactional nature of ethical work practices/programs (codes of conduct, corporate values, culture/climate, etc.) and employee characteristics (i.e., personality, attitudes, perceptions, moral philosophies/ideologies, etc.) (e.g., Ferrell and Gresham 1985; Ferrell et al. 2007; Hunt and Vitell 2006; Jones 1991; Treviño 1986; Wotruba 1990). Many of these frameworks also incorporate, either partially or wholly, Rest’s (1986) four-step framework of ethical reasoning, which includes variations of the sequential factors “awareness of an ethical issue,” “ethical judgment,” “ethical intentions,” and “ethical behavior.” Within entrepreneurship and ethics research, prior work has utilized the Rest (1986) model to analyze whether there are dissimilarities in the ethical reasoning of entrepreneurs and those of managers in large firms, even suggesting that entrepreneurs may possess a stronger capacity for moral decision making than do managers in large companies (Teal and Carroll 1999).

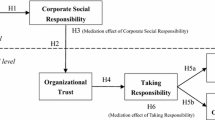

Consistent with such thinking/inquiry, new research should identify how work and organizational factors might motivate entrepreneurs and employees of smaller businesses to think and behave inappropriately (Miller 2014). There is also a need for personality research in the field of entrepreneurship/small business management, particularly studies that identify the negative individual traits that lead to counterproductive behaviors and incivility in smaller firms (Klotz and Neubaum 2016). Consequently, the impact of ethics code presence in smaller organizations, a contextual factor, on locus of control, social aversion/malevolence, and ethical judgment is explored in the current study (see Fig. 1). This investigation also explores how small business employees’ internal locus of control and social aversion/malevolence, both individual factors, impact their ethical judgments of incivility directed at a coworker. The overall focus is on the characteristics and experiences of employees working for smaller organizations rather than on lone entrepreneurs in nascent ventures.

This research is relevant for several reasons. The body of work that investigates entrepreneurial ethics is relatively sparse compared to its overall importance in the economy (Hannafey 2003). While much empirical work in the field of business ethics has focused on larger firms, providing a significant knowledge base (Treviño et al. 2006), research into small business/entrepreneurial ethics is lacking (Hannafey 2003), particularly on the empirical side. Indeed, prior research has not fully considered how employees working for small/entrepreneurial businesses may differ from others in their understanding of ethical standards. One early empirical investigation of small business ethics (Longenecker and Schoen 1975) indicated that attitudes may vary among individuals working in small and large organizations, prompting various questions about how entrepreneurs, compared to managers of larger firms, may hold unique ethical principles/attitudes, deal with unique ethical concerns, and react differently to ethical situations; at the extreme, some researchers have suggested that entrepreneurs launching new ventures may discount their personal beliefs to be successful (Fisscher et al. 2005). Spence and Rutherford (2003) also stressed that the ethical conduct of individuals working for larger organizations should not be applied to persons working for small businesses. These realities point to a need for additional research that explores ethical issues in smaller organizations, particularly those related to ethical standards and practices that may be unique to this context.

Longenecker et al. (1989, p. 27) also claimed that managerial approaches utilized in smaller organizations “…reflect to a greater degree the personality and attitudes of the entrepreneur,” which implies that personality characteristics may in some way be related to the ethical practices found in small businesses. Entrepreneurs, known for their internal loci of control (Miller et al. 1982), fundamentally shape an entrepreneurial organization’s ethical culture (Hannafey 2003). However, far less is known about the loci of control of the employees who work for them, including how such perceptions of individual control may be associated with facets of organizational ethics, workplace incivility, and ethical decision making.

Other personal characteristics are likely germane to these issues. Researchers (e.g., Klotz and Neubaum 2016; Miller 2014) have recently called for entrepreneurship scholars to study how negative personality traits and entrepreneurial outcomes are interrelated, especially with a deeper view of Machiavellianism and psychopathy, which, together with narcissism (O’Boyle et al. 2012), constitute the Dark Triad. Klotz and Neubaum (2016) emphasized the importance of scholars building upon the foundational work in personality established in the psychology and organizational behavior literature over the past 100 years, rather than forging new ground with an “entrepreneurial personality” as a unique phenomenon (Klotz and Neubaum 2016).

Discriminating among the three elements of the Dark Triad (i.e., narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy), researchers (Rauthmann and Kolar 2013; Volmer et al. 2016) have suggested that in contrast to narcissism, which in milder forms is known to be adaptive (Rhodewalt and Peterson 2009), the duo of “Machiavellianism and psychopathy” constitute the “Malicious Two” (Volmer et al. 2016, p. 414), with the latter two constructs specifically “…related to stronger malevolence and negative perceptions from others.” An individual with Machiavellian tendencies possesses the desire and predisposition to manipulate situations. Psychopathy is associated with antisocial tendencies, a lack of restraint typically displayed in a disregard for social conventions, and impulsivity (Boddy 2014). Machiavellianism and psychopathy share a common denominator of violating social norms, typically for personal gain (O’Boyle et al. 2012). They appear to converge with similar interpersonal styles and antagonistic behaviors (Jones and Paulus 2010; Rauthmann and Kolar 2013) and show tendencies toward callousness and exploitation of others (Rauthmann and Kolar 2013). The Malicious Two may be particularly impactful in the area of entrepreneurship, and, to our knowledge, this duo of socially averse/malevolent styles have not been researched within the realm of entrepreneurial/small business ethics. Applying existing personality research on the Malicious Two to entrepreneurial/small business contexts therefore appears to be a meaningful way to advance the study of ethical behavior in smaller firms.

Literature Review

Ethics Code Presence and Ethical Judgment

An ethics code is “a distinct and formal document containing a set of prescriptions developed by and for a company to guide present and future behavior on multiple issues of at least its managers and employees toward one another, the company, external stakeholders and/or society in general” (Kaptein and Schwartz 2008, p. 113). As the foundation for an ethics program, the code of ethics helps foster an ethical culture (Kaptein 2009), and it is an efficient means to signal ethical intentions (Treviño and Weaver 2003). As such, an organization’s code of ethics often underscores its ethical norms and values, which are ideally adopted by its members (Schwartz 2001; Valentine and Barnett 2002). Functioning “as a written document containing general statements intended to serve as principles that underlie acceptable and unacceptable types of behavior (Singh 2006; Stevens 2009), a formal code of ethics is the most common concrete organizational instrument…” that facilitates ethical reasoning and conduct (Ruiz et al. 2015, p. 728).

Although affected by many managerial issues/concerns (Kaptein and Schwartz 2008; Ruiz et al. 2015), which may even be more challenging in smaller organizations, “…such codes are thought to promote ethical behavior by heightening awareness and clarifying expectations…” of employees (Ruiz et al. 2015, p. 728). These challenges are mirrored in the comparative numbers that are found in larger versus smaller organizations. Some studies show that more than 60% of bigger firms have a written ethics code and 38% have a program of ethics training, while only 33% of smaller firms have a written ethics code and 7% have a program of ethics training (Morris et al. 2002; Robertson 1991). These numbers might suggest that smaller firms do not face the same volume and variety of ethical concerns as do larger organizations, but they may also underscore the reality that smaller firms have far fewer workers and available resources to develop significant ethics programs. It could be that small businesspersons reference a code of their own or follow professional guidelines in the absence of an ethics code (Vyakarnam et al. 1997), possibly precipitating ethical transgressions if such guidelines conflict with prescribed norms in a small business. Unfortunately, little research has explored these issues, particularly the impact of codes on the ethical reasoning of individuals employed in smaller organizations.

Regardless of the presence of ethics codes in small firms, extant research has explored their relationship with individual ethical reasoning in a broad sense. O’Fallon and Butterfield (2005), across 20 studies, found a positive relationship between the two variables. More recently, McKinney, Emerson, and Neubert (2010, p. 505) studied the impact of ethics codes on ethical beliefs, with findings showing that businesspersons in organizations that had ethics codes were “…significantly less accepting of ethically questionable behavior toward most stakeholders.” However, a review of empirical studies (see Loe et al. 2000) indicated that several researchers, primarily with undergraduate student populations, found that an awareness of ethics codes does not significantly influence ethical reasoning or actions. Further, another review (see Treviño et al. 2006) found that the impact of ethics codes was apparently marginal.

Even though these results are mixed, there is still reason to believe that employee ethics is influenced by institutionalized ethical practices, including the advancement of formal ethics codes (McDonald and Zepp 1990; Vyakarnam et al. 1997). More important than the presence of ethics codes, employees should be aware of their existence for these codes to be impactful (Valentine and Barnett 2003). We contend that, when employees in smaller firms are keenly aware that ethics codes are present, they should be motivated to think and act ethically because they perceive greater psychological proximity to and intimacy with a work environment that employs fewer individuals and is thus more normatively impactful. Based on these ideas, the following relationship for smaller organizations is therefore proposed:

H1

The presence of an ethics code in a smaller organization is associated with more ethical judgments.

Ethics Code Presence, Social Aversion/Malevolence, and Internal Locus of Control

There is reason to believe that ethics codes developed in smaller organizations have the capacity to influence employees’ dispositions, key individual characteristics that likely have some bearing on workplace incivility and ethical reasoning. Codes function this way by creating a profound and prevailing ethical work environment that shapes the personal attitudes of employees in relation to both relatedness to others and self-evaluation. Two particularly relevant characteristics include social aversion/malevolence (Machiavellianism and psychopathy, or the Malicious Two) and (internal) locus of control because they represent behavioral, relational, and experience-based tendencies shaped by the social/cultural norms experienced by employees at work, which can be influenced by ethics codes.

Since the presence/awareness of ethics codes should contribute to increased levels of ethical conduct and stronger perceptions of organizational ethics among employees (e.g., Ferrell and Skinner 1988; McCabe et al. 1996; Valentine and Barnett 2003), codes should also precipitate incremental decreases in individual counterproductive beliefs/tendencies that prompt an uncivil work environment. In other words, ethics codes prescribe acceptable behavioral norms, thus reducing employee attitudes and conduct consistent with social aversion/malevolence that lead to the mistreatment of others. Codes also form the backbone for ethical leadership (in this case small business leaders) and behavioral control systems (Brown and Treviño 2006), actively minimizing poor judgment and promoting ethical behavior. Although employees with characteristics consistent with social aversion/malevolence may be predisposed to function negatively against generally accepted social norms, clear rules of what constitutes misconduct provides expectations to avert incivility. It is likely that these relationships are particularly profound in smaller organizations because there is often less direct oversight of employees (i.e., fewer managerial personnel) and fewer established company policies; ethics codes would serve to fill some of the gaps in leadership and behavioral control mechanisms found in smaller firms. The following hypothesis is therefore presented:

H2

The presence of an ethics code in a smaller organization is associated with weakened social aversion/malevolence.

Locus of control, an important consideration in small business ethics, refers to individuals’ perceptions about whether the consequences of their behaviors are within (internal) or beyond (external) their own personal control (Schjoedt and Shaver 2012; Treviño 1986). Pandey and Tewary (1979) found that individuals planning to start small enterprises exhibited internal loci of control; they thought that they influenced their own outcomes, rather than their circumstances. Further, Boone et al. (1996) found that firms with CEOs that had an internal locus of control performed better than CEOs who had an external locus of control. We know less about the employees of entrepreneurial ventures and small businesses, particularly when those employees are faced with an ethical scenario at work. In general, individuals gravitating towards an external locus of control may consistently think that ethical problems are out of their control, while individuals with an internal locus of control feel empowered to control situations with a willingness to accept personal responsibility for their own actions (Forte 2004; Treviño 1986).

Locus of control is sometimes treated as a single trait for simplicity in empirical research (e.g., Judge and Bono 2001), but there is psychometric evidence to suggest that locus of control, self-esteem, neuroticism, and generalized self-efficacy may be reflections of a similar higher-order construct (Judge et al. 2002). Further, locus of control may be conceptualized within a specific context, such as within a work domain. Spector (1988) found a correlation of .57 between “general locus of control” and “work locus of control,” suggesting that perhaps there may be a stable (i.e., trait) element and a situational component of locus of control that may vary by environment, such as in a small business context. For example, Schjoedt and Shaver (2012) stressed the need to consider the context in their analysis of the construct of locus of control within an entrepreneurial domain. The common theme in these studies is that context matters.

Given a particular small business context that either has or does not have ethics codes, behavior may be situation dependent and expected to differ, though there may be a “gradient of generalization from one situation to another” (Rotter 1990, p. 491). Treviño (1986) stressed that situational influences have a strong impact in reducing the role of an individual’s internal/external locus of control. Regardless of where employees fall on the spectrum of internal to external locus of control in terms of their personality style, we are suggesting that there may be increased perceived control in the presence of ethics codes that guide employees in small businesses. The presence of an ethics code shows employees that their organization is ethical (Adams et al. 2001), thus leading employees to believe that they have the ability to control their environmental choices when faced with an ethical decision. This, in turn, should lead to increased employee perceptions of internal (versus external) locus of control (i.e., ethics code ⟶ enhanced perceptions of internal-focused locus of control). Stated differently, the presence of an ethics code should provide employees with confidence that they can control their ethical choices because the organization is signaling that it supports an ethical environment.

These insights prompt the notion that the behavioral prescriptions embedded within ethics codes found in smaller organizations may both facilitate the stable trait element of locus of control and influence a more situational perception of internal control over an outcome, particularly those that relate to a perceived ethical situation or problem associated with workplace incivility. The following hypothesis is therefore presented:

H3

The presence of an ethics code in a smaller organization is positively associated with locus of control that is more internal in nature.

Social Aversion/Malevolence and Ethical Judgment

There is also reason to believe that social aversion/malevolence is related to ethical reasoning, especially in situations that involve perceived workplace incivility. For instance, Cohen et al. (2014) found moral disengagement to be positively associated with Machiavellianism (r = .44). Specific to ethical judgments given scenarios of questionable selling actions, individuals scoring higher on measures of Machiavellianism viewed questionable selling practices as more acceptable (Bass et al. 1999). Valentine and Fleischman (2017) also determined that Machiavellianism was negatively related to perceived ethical issue importance in a workplace bullying situation.

Prior research has also suggested that individuals with psychopathic tendencies have difficulty following the steps of the ethical reasoning process (Cohen et al. 2014). Jackson et al. (2013) suggested in their framework of ethical decision-making dissolution that poor cognitive moral development, low ethical sensitivity, and a willingness to break rules, characteristics associated with social aversion/malevolence, would negatively impact the recognition of ethical situations. One study in particular provides evidence highlighting these relationships. Stevens et al. (2012) found that the link between the constructs “psychopathy” and “unethical decision making” was mediated by “moral disengagement.” In their study, a sample of 27 undergraduates reacted to four ethical scenarios containing various business dilemmas (e.g., “cutting corners” in production, failing to disclose errors in financial reports, etc.) and were asked to respond with their willingness to act unethically given the issues explored in each vignette. The findings showed that psychopathy was associated with increased self-reported willingness to act unethically (Stevens et al. 2012). Finally, Valentine et al. (2018) found that psychopathy was associated with weakened ethical reasoning (i.e., decreased ethical issue importance and ethical intention) in an ethical situation that involved the mistreatment of a coworker.

Given the positive relationship between the Malicious Two traits, psychopathy and Machiavellianism (or social aversion/malevolence in this study), with unethical decision making, it follows that as levels of social aversion/malevolence increase, ethical judgments of workplace incivility would decrease. This occurs because there is a deterioration of the standards associated with how one should constructively relate to others at work. Consequently, the following hypothesis is offered:

H4

In a smaller organization, increased social aversion/malevolence is negatively associated with judgments that workplace incivility is unethical.

Internal Locus of Control and Ethical Judgment

The interactionist perspective of ethical reasoning (see Treviño 1986) emphasizes locus of control as a key individual factor that moderates the link between moral judgment and ethical behavior. Those individuals exhibiting an external locus of control should be less willing to accept responsibility for the outcomes of unethical behavior, placing blame or reliance on external forces. Conversely, individuals displaying an internal locus of control should be more likely to accept responsibility for outcomes, utilizing an internal ethical assessment (or “ethical compass”) to guide their actions. However, as previously stated, a predisposition towards internal or external locus of control can be moderated and shaped by contextual cues, cues that should be particularly normative in smaller organizations given the increased psychological and integrated closeness found within a more intimate work environment. Regardless of one’s view of the emergence, development, and evolution of locus of control, the following hypothesis is found in prior research (i.e., Craft 2013; O’Fallon and Butterfield 2005; Treviño and Youngblood 1990) and extended and tested in a small business context as follows:

H5

In a smaller organization, a more internal locus of control is positively associated with judgments that workplace incivility is unethical.

Method

Data

After receiving questionnaire feedback from two respected researchers in organizational ethics/sustainability, information was gathered from a U.S. national sample of 3000 selling professionals; information used to contact individuals was purchased from a marketing research firm. Selling professionals were identified as a useful source for information because it is common for them to deal with ethical issues and incivility in the workplace (e.g., Darrat et al. 2010; Jelinek and Ahearne 2006; Valentine et al. 2015; Yoo and Frankwick 2013). Questionnaire packets were mailed to individuals, resulting in the return of 95 forms in the first round. After a period of about 3 months, a second round of questionnaire packets was sent to individuals, resulting in another 43 forms. Consequently, a total of 138 questionnaires and an approximate 4.73% response rate (after accounting for ineligible forms) were obtained. This low response rate was likely driven by the highly sensitive nature of the topics (individual ethics, workplace bullying, incivility, etc.) explored in this research. Comparisons of individual responses across the two waves for demographic and key variables of this study indicated no significant differences (Armstrong and Overton 1977).

Given the low response rate of this initial collection of data, an additional convenience sample of selling professionals employed in different businesses operating in a region of the southern U.S. was also secured to increase the overall sample size and facilitate hypothesized relationships. To support our multivariate and univariate analyses with a power of .80 and a significance level (alpha) of .05, the recommended sample size ranged from 180 to 196 participants (respectively) for a medium effect size using an approximation of the G*Power sample size calculator (Faul et al. 2007). Once again, many of these employees were identified because their jobs included selling activities, which enhanced the likelihood that a more homogenous sample of professionals would be secured when the samples were combined. Consequently, our targeted convenience sample was in no way haphazard, as some definitions of convenience samples suggest.

There are limitations associated with combining probability and convenience samples, namely the potential bias in nonprobability samples (Kim et al. 2010). However, securing a convenience to supplement an existing probability sample may be appropriate when the convenience sample is inexpensive to gather and relatively large in relation to the probability sample (Schonlau et al. 2002). In addition, many studies published in the Journal of Business Ethics and other top-tier journals have utilized combined samples (i.e., probability and nonprobability and/or multiple convenience) to investigate a variety of ethical issues (see Brower and Shrader 2000; Gok et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2010; McClaren 2015; Pearce 2013; Strand 2014; Valentine et al. 2010). In terms of sampling design, due to practical limitations, researchers may rely solely on convenience samples to study ethical issues (e.g., Randall and Gibson 1990; Roof 2015). In the current study, collapsed samples from the two different data collection methods allowed for a broader overall sample, consisting of both national representation augmented by a regional convenience sample. Since we combined two different samples containing identical email survey questions, we controlled for data collection method in our multivariate and univariate analyses, with the differences between the two samples being generally insignificant in complete models containing all of the control and focal variables.

Individuals were given questionnaires for completion, and additional questionnaires were provided at times so that other employees might participate; completed questionnaires were collected either immediately or later. A total of 246 questionnaires were obtained from this second round of data collection, and after these identical survey forms were combined with the national sample, the total sample included 384 questionnaires. From this total count, 189 questionnaires completed by individuals working for companies that employed “fewer than 100” individuals were separated from the combined sample for use in this current investigation.

Employees had an average of age 39.30 years; 60.6% of them were male, 76.3% were white, and 53.2% were married. With regard to education, 17.7% of the employees indicated that they had a high school diploma, 51.1% had some college, and 18.8% had a Bachelor’s degree. Reported work experiences indicated that 88.1% of individuals were employed full-time, and that they had an average of 8.38 years of job tenure. Many claimed to be “sales/marketing” managers (41.4%), some of them worked as general managers (12.2%), and many worked in “other” types of jobs (30.4%). Individuals also disclosed a variety of business/industry information about their employers. For example, 34% of the organizations conducted business in “wholesale/retail,” 16% in “manufacturing/construction,” 12.2% in “services,” 4.3% in “communications,” and 2.1% each in “high-tech,” “banking,” and “insurance.” Almost 58% of organizations had an ethics code that influenced work behavior.

A majority of the employees claimed to be sales professionals (84%), meaning that a component of their work involved selling or managing sales activities. However, almost all of them called on others to make sales, dedicated some of their time to selling, and/or were involved with sales accounts based on responses provided on a series of demographic items. We therefore considered these participants to be sales-oriented employees in this study, despite their responses to a direct question about being a sales professional. Indeed, many of the disclosed job classifications showed that many sales-based positions were included in the sample, including “real estate” professionals, “retail and hospitality” employees, “customer contact” workers, and others. Therefore, we define selling professionals somewhat broadly in the present study. We posit that this definitional strategy is appropriate given our broad study purposes because we wished to gather feedback from a wide variety of individuals to assess our hypotheses. Subjects had on average 13.61 years of “selling experience” (of 186 answers provided), they made on average 8.64 “sales calls per day” (of 168 answers provided), they dedicated an average of 24.55 “hours per week” on “selling activities” (of 179 answers provided), and they dealt with an average of 233.99 “sales accounts” (of 155 answers provided).

Measures

Ethics Scenario and Ethical Judgment

An ethics scenario highlighting workplace bullying and other socially aversive/malevolent behaviors was used to prompt respondents’ ethical judgments. Ethics research often utilizes such vignettes to assess individual ethical reasoning in different business situations (e.g., Alexander and Becker 1978; Barnett 2001; Reidenbach and Robin 1990). The scenario utilized in this study, which appears in past work (Valentine and Fleischman 2017, p. 298; Valentine et al. 2018, p. 149), presents circumstances where a salesperson is mistreated by a coworker:

Situation: Kim is a seasoned salesperson in an office supply firm that services many large corporate clients. A year ago, she was given several new sales accounts that had high potential, mainly because of her seniority in the sales department, as well as her popularity, easy-going nature, and preferences for teamwork (i.e., she sometimes gives sales leads away to help struggling associates). Unfortunately, she has been unable to sell enough merchandise to these new clients, and her current level of sales performance only “meets expectations” according to recent appraisals received from her sales manager. Jocelyn, a relatively new member of the sales department, subscribes to a different approach to selling that involves individualistic and assertive tactics, excessive networking with others, and impression management around important people, qualities that have often enabled her to get good sales leads and assignments and to effectively close deals. Jocelyn is upset because she thinks that Kim is not selling enough given her good sales leads, she’s too concerned about getting along with others, and she’s not political enough. Consequently, Jocelyn believes that Kim’s new accounts should be assigned to her to oversee and manage.

Actions: Jocelyn meets individually with members of the sales department to convince them that Kim’s new accounts should be assigned to her. While many disagree with Jocelyn, she convinces a core group of salespeople, including the sales manager, that Kim’s new clients should be given to her, which occurs during Kim’s next performance appraisal. Feeling empowered by this decision, Jocelyn begins to ignore, isolate, and criticize those who disagreed with her, while at the same time strengthening her relationships with those who supported her.

In particular, the coworker shows traits and behaviors similar to the characteristics embedded in the Malicious Two. The coworker acts in a political and self-serving manner similar to Machiavellianism, and she shows proclivities toward subclinical psychopathy by behaving aggressively, exhibiting low empathy, and harming the salesperson.

Along with other decision-making measures, the single item for “ethical judgment” followed the scenario with the prompting text “Next is a set of adjectives that allow you to evaluate Jocelyn’s actions described in the situation.” This presentation required respondents to reference the situation’s characteristics and answer a seven-point semantic differential scale containing the opposing words “Ethical” and “Unethical.” Higher item scores showed stronger opinions that the negative acts detailed in the scenario were considered unethical by the respondents. This single-item ethical judgment measure, used alone or with additional items, as well as other similar one-item scales, have been utilized effectively in previous work to assess the ethicality of actions highlighted in a variety of ethics scenarios and situations (e.g., Barnett et al. 1994; Fleischman and Valentine 2003; Hunt and Vasquez-Parraga 1993; Mayo and Marks 1990; Reidenbach and Robin 1988; Vitell and Ho 1997).

Social Aversion/Malevolence

Respondents’ social aversion/malevolence was measured with six items taken from the primary subscale of the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (Levenson et al. 1995; Valentine et al. 2018). Sample items include “For me, what’s right is whatever I can get away with” and “I enjoy manipulating other people’s feelings.” Opinions were provided on a seven-point scale anchored by “1 = Strongly Disagree” and “7 = Strongly Agree,” and item scores were averaged to have higher values indicating elevated, yet subclinical psychopathy. The scale had a coefficient alpha of .808 in this study. A five-item measure of Machiavellianism was also used to assess social aversion/malevolence among respondents (Christie and Geis 1970; Valentine and Fleischman 2003). Sample items include “It is wise to flatter important people” and “It is hard to get ahead without cutting corners here and there.” Items were rated on a seven-point scale including “1 = Strongly Disagree” and “7 = Strongly Agree,” and item scores were averaged so that higher values showed increased Machiavellianism. The scale had a coefficient alpha of .730 in this investigation.

A factor analysis using principal components extraction was conducted to evaluate the dimensionality of the composite scores for subclinical psychopathy and Machiavellianism. The results indicated a one-factor model with an initial eigenvalue of 1.552, 77.615% of explained variance, and factor loadings of .881 for both measures. Based on these satisfactory findings, as well as established conceptualizations of the “Malicious Two” (Volmer et al. 2016, p. 414), the average values for psychopathy and Machiavellianism were added together and divided by a value of “2” to obtain an overall composite measure for the social aversion/malevolence construct. The coefficient alpha of this combined overall measure was .709.

Internal Locus of Control

Three items used by Lumpkin and Hunt (1989) were used to evaluate employees’ internal locus of control. This three-item measure is slightly modified from a three-item “internal control” scale developed by Lumpkin (1985), which was based on the original Rotter (1966) locus of control instrument. Lumpkin and Hunt (1989) reported a coefficient alpha score of .617, which provides some evidence that the measure has adequate internal consistency reliability, particularly for exploratory research. Sample items are “What happens is my own doing” and “Getting people to do the right things depends upon ability not luck.” Responses were provided on a seven-point scale anchored by “1 = Strongly Disagree” and “7 = Strongly Agree,” and item scores were summed and divided by the number of items so that higher composite values indicated a more internal locus of control. The scale’s coefficient alpha in this investigation was .722.

Presence of an Ethics Code

The presence of an ethics code in the smaller businesses was determined with a single item that enabled respondents to indicate whether their employers had an ethics code that governed work conduct within the ranks of the organization. The item is “Does your organization have an ethics code that governs work conduct? (1) No (2) Yes.” Other studies have used similar demographic items to determine the availability and utilization of different programs to manage organizational ethics (Valentine and Barnett 2002; Valentine and Fleischman 2008; Valentine et al. 2015).

Controls

Two control variables were included in the analysis. For instance, the presence of social desirability is common in ethics research (Randall and Fernandes 1991), so it was necessary to account for this individual tendency. We posit that controlling for social desirability was especially important in the present study because of the highly sensitive nature of ethical issues related to aversion/malevolence. We therefore controlled for this important form of bias in each of our multivariate and univariate analyses. An abbreviated ten-item measure was used to evaluate respondents’ social desirability (see Crowne and Marlowe 1960; Fischer and Fick 1993; Strahan and Gerbasi 1972), and all items were evaluated with a seven-point scale specified as “1 = Strongly Disagree” and “7 = Strongly Agree.” Several factor analyses using principal components extraction facilitated the selection of the most appropriate items, which were “I’m always willing to admit it when I make a mistake” and “I always try to practice what I preach.” Item scores were averaged with higher values indicating increased social desirability. The scale’s coefficient alpha value was .739. As stated previously, a sample variable that indicated whether observations were from the national sample (coded as “1”) or regional sample (coded as “2”) was also included in the statistical models to account for any potential response differences across the two separate data collection rounds.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were estimated to evaluate the magnitude of the key variables, and correlations were examined to determine how variables were interrelated. Various multivariate and univariate models were specified to assess the hypothesized relationships in this study. Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) and univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) were used to identify how the presence of an ethics code impacted ethical judgment, social aversion/malevolence, and internal locus of control while controlling for social desirability. Another ANCOVA model was specified to determine how the presence of an ethics code, social aversion/malevolence, and internal of control were related to ethical judgment while controlling for social desirability.

Results

Variable Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 1 outlines the variable descriptive statistics and correlations. The mean scores for ethical judgment and internal locus of control were moderately high, which suggested that the employees perceived that the actions highlighted in the scenario were generally unethical, and that they were reasonably empowered with personal control. The mean value for social aversion/malevolence was low, indicating that employees had only slight inclinations toward counterproductive interactions with others. The mean value for the ethics code variable showed that a slight majority of employers had ethics codes that governed work conduct. The social desirability mean value was also moderately high, implying that managing the impressions of others was an issue among the respondents. The mean value for sample type (national vs. regional) indicated that the regional sample was slightly larger than the national sample.

The correlation analysis showed that the presence of an ethics code in smaller organizations was positively related to employees’ internal locus of control and ethical judgment (p < .05), and that an internal locus of control was positively related to ethical judgment (p < .001). Social aversion/malevolence was also negatively related to ethical judgment (p < .001). These identified relationships provided some support for the idea that codes of conduct can be used to empower employees to make ethical decisions in situations involving workplace misconduct, specifically situations impacted by the Dark Triad traits. The findings also underscore the idea that social aversion/malevolence can harm ethical decision making in these same situations. Finally, three of the four study variables were associated with the social desirability measure (at the .01 level or better), and two of the four study variables and the social desirability measure were associated with the sample variable (at the .01 level or better), which provided support for the specification of these two factors as controls in the analysis.

Multivariate and Univariate Analyses

Table 2 highlights the MANCOVA and ANCOVA results. The multivariate model specifying ethical judgment, social aversion/malevolence, and internal locus of control as the dependent variables, social desirability and sample type (national vs. regional) as controls/covariates, and ethics code presence as the fixed factor generated significant Wilks’ lambda values for both social desirability (p < .001) and ethics code presence (p < .05). The univariate model specifying ethical judgment as the dependent variable indicated that, after controlling for social desirability (p < .01), which was positively related to ethical judgment (β = .310, se = .093, t value = 3.332, p = .001), and sample type (national vs. regional), having an ethics code in smaller organizations resulted in a significant increase in employees’ ethical judgment in the ethics scenario involving a person who exhibited traits/behaviors related to the Dark Triad (p < .05); the parameter estimate for not having an ethics code was negatively related to ethical judgment (β = − .624, se = .242, t value = − 2.576, p = .011). These results provided adequate statistical support for Hypothesis (1). After controlling for social desirability (p < .05) and sample type (p < .10), the univariate model specifying social aversion/malevolence as the dependent variable indicated that having an ethics code did not result in a significant decrease in employee’s counterproductive tendencies; social desirability was negatively related to social aversion/malevolence (β = − .151, se = .062, t value = − 2.446, p = .016), the regional sample was associated with increased social aversion/malevolence (β = .315, se = .168, t value = 1.878, p = .062), and the parameter estimate for not having an ethics code was not related to social aversion/malevolence (β = .057, se = .161, t value = .353, p = .725). Overall, these findings did not support Hypothesis (2). Finally, the univariate model specifying internal locus of control as the dependent variable indicated that, after controlling for social desirability (p < .001), which was positively related to internal locus of control (β = .415, se = .061, t value = 6.803, p = .000), and sample type, having an ethics code resulted in a significant increase in employees’ internal locus of control (p < .05); the parameter estimate for not having an ethics code was negatively related to internal locus of control (β = − .4.00 se = .159, t value = − 2.509, p = .013). These results provided adequate statistical support for Hypothesis 3.

The results of the second ANCOVA, which specified ethical judgment as the dependent variable, social aversion/malevolence, internal locus of control, social desirability, and sample type (national vs. regional) as the controls/covariates, and ethics code presence as the fixed factor, are summarized in Table 3. Employees’ social aversion/malevolence was significantly related to ethical judgment in the situation involving a person who exhibited characteristics associated with the Dark Triad (p < .001), and a negative parameter estimate was identified between the two variables (β = − .479, se = .116, t value = − 4.139, p = .000). These results provide strong support for Hypothesis 4. Employees’ internal locus of control was significantly related to ethical judgment (p < .10), and a positive parameter estimate was identified between the two constructs (β = .229, se = .117, t value = 1.954, p = .053). These results provide sound support for Hypothesis 5. Finally, ethics code presence in smaller organizations is positively associated with more ethical employee judgments (p < .05), and a negative parameter association was identified between not having an ethics code and ethical judgment (β = − .506, se = .235, t VALUE = − 2.155, p = .033). These findings provided additional support for Hypothesis 1.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to utilize the small business/entrepreneurial context to investigate the ethical inclinations of employees by specifically focusing on those who display dark personality tendencies of social aversion/malevolence. We measure social aversion/malevolence using a construct that combines dual aspects of subclinical psychopathy and Machiavellianism, elements that the literature describes as the “Malicious Two” (Volmer et al. 2016, p. 414). To operationalize this broad research aim, the study evaluates the variable interrelationships between the presence of ethics codes in smaller organizations and employees’ internal locus of control, social aversion/malevolence, and ethical judgment of workplace incivility directed toward a coworker.

Overall, our statistical findings supported four of our five working hypotheses. For example, Hypothesis 1 was supported by the conclusion that the presence of an ethics code was positively associated with judgments that the employee mistreatment in the scenario was unethical. Hypothesis 3 was supported by the inference that the presence of an ethical code was positively associated with internal locus of control. Hypothesis 4 was supported because increased social aversion/malevolence was associated with decreased judgments that the employee mistreatment was unethical. Hypothesis 5 was supported because small business employees’ internal locus of control was positively associated with ethical judgments.

Managerial Implications

Our finding that the presence of an ethics code was positively associated with judgments that social aversion/malevolence was unethical provides a number of important managerial implications. For example, codes of conduct essentially proxy for ethical standards and directives within the small business, which provides formal organizational expectations for acceptable behavior (Fernández and Camacho 2016). This finding is especially important because small businesses can be more informal than formal (Fassin et al. 2011; Jenkins 2006; Spence and Lozano 2000) with regard to institutionalizing behavioral norms. Therefore, this result provides evidence that small business managers who wish to institutionalize an ethical environment in the firm should create and then communicate a formal ethics code if they do not already have one. If a code already exists, it is in the best interest of small business leaders (i.e., managers, entrepreneurs, owners, operators) to periodically update the code for relevance and communicate its content to employees, thus reemphasizing its significance. It is important that leadership pragmatically emphasizes that the code is necessary to improve employee ethical awareness, ethical reasoning, and decision-making skills.

The presence of an ethics code in a small business is also significant because it is positively associated with employee’s internal locus of control. Small business managers are wise to promote internal locus of control in their employees because workers with this viewpoint perceive themselves as having power and influence over their environment. This is important because individually empowered employees might be more likely to take personal responsibility for their own ethical actions (Forte 2004; Treviño 1986) and to make positive interventions regarding fellow employees who display dark personality tendencies in the small business workplace. Similarly, our related finding that small business employees’ internal locus of control is positively associated with judgments that workplace incivility is unethical further underscores why employee perceptions of empowerment are helpful to promote workplace ethical reasoning. Employees who perceive that they have control over their work environment should be much more likely to initially recognize that an ethical dilemma exists and then to subsequently make an accurate judgment that employee mistreatment is unethical. In contrast, small business employees with an external locus of control should be much more likely to experience helplessness by either ignoring or tolerating aversive/malevolent behaviors in the workplace. This suggests a decreased likelihood that externals will judge such behaviors as unethical.

One of the particularly important conclusions of the study is that social aversion/malevolence is negatively associated with judgments that employee mistreatment is unethical. Stated differently, this finding indicates that small business employees who display dark personality tendencies are less likely to perceive that social aversion/malevolence is unethical. While this conclusion has significant repercussions on the ethical context of any organization, this finding has even more serious implications in the small business context. For example, an obvious extension of this finding relates to the scale of a small business; due to a smaller number of personnel, workers who display social aversion/malevolence in the workplace will likely have a relatively greater impact on fellow employees. The problem is especially acute if the toxic worker is a member of the management team, or worse still, if they are the sole owner-manager, since arguably management in the small business context has an even greater influence on the “tone at the top” than does management in larger businesses (Vitell et al. 2000; Jenkins 2006). The scale of a small business also exacerbates the likelihood that aversive/malevolent behaviors will spread in the workplace, as such “Malicious Two” (Volmer et al. 2016, p. 414) dark behaviors quickly become the behavioral norm.

Our finding that the presence of an ethics code was not significantly and negatively related to social aversion/malevolence is noteworthy. Although the study findings noted above suggest that the presence of the code is useful for enhancing ethical judgments and internal locus of control, the presence of the code in our small business salesperson sample apparently is not sufficient to arrest uncivil behavior. The existence of an ethics code related to ethical decision making is sometimes not enough and research has suggested that effective enforcement may also be needed (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010), as “…ethics-related codes and policies can be…” missed “…in day-to-day decision making” (Ruiz et al. 2015, p. 728). Communicating the content of the code is also important (Ruiz et al. 2015).

Small business leadership must therefore diligently take proactive steps to manage the ethical context beyond formalities such as establishing codes of ethics. This suggests that management should actively reinforce the code by reminding employees of the importance of the code during meetings and workshops (Fernández and Camacho 2016). More importantly, leadership should remind employees that the code is a pragmatic and necessary directive element that governs behavioral ethical expectations of the business in general, as well as employee interactions with each other and with customers, in particular. Stated differently, leadership needs to pragmatically emphasize that, without a code of conduct to help govern ethical interactions in the workplace, the business becomes riskier, which could ultimately threaten its reputation and viability as a going concern, should uncivil behaviors become normalized.

In addition to communicating an ethics code to employees, it is also important for management to specify rewards for ethical behavior that facilitates positive employee relations, as well as penalties for the uncivil mistreatment of employees (e.g., Ashkanasy et al. 2006). If punishment for aversive/malevolent behaviors is not swift and appropriate, it is likely that employees will ignore the ethical code as mere window dressing. Clearly, top management must themselves abide by the ethics code and “walk the talk” because leadership in smaller organizations generally plays an even more influential role on the ethical context than in larger businesses (Jenkins 2006; Vitell et al. 2000).

Behavioral Influence of Social Aversion/Malevolence

The typical small business is generally less formal given its small size, is strained financially, often employs workers with less formal education, and requires employees to wear “multiple hats” in terms of job responsibilities. Many small businesses are characterized by authoritarian leaders (Spence and Lozano 2000). Our small business sample is composed primarily of individuals with selling backgrounds, so these people are likely to face ethical dilemmas due to the high pressure, risk taking, multitasking (Spence and Lozano 2000), and boundary spanning associated with the marketing discipline. Furthermore, small business sales professionals are often isolated from the office and thus may be more difficult to monitor ethically. Together, these personal and job characteristics suggest that small business employees in our sample likely face considerable stress that may lead some to compromise their ethics by engaging in harmful/uncivil behaviors to meet service performance deadlines and quota commission mandates. Such conduct profoundly influences not only the victim, but also bystanders, which may quickly transform accepted norms of behavior to create a toxic environment. Additionally, many small businesses lack formal internal controls and separation of duties that unintentionally present employees with numerous occasions to engage in opportunistic behaviors that further damage the ethical context. Worse still, a toxic environment from such acts can invariably harm customer interactions in the sales context, which eventually damages the organization’s reputation and long-term viability.

Strategies to Arrest Social Aversion/Malevolence

Typical prescriptions for ethical transformation in a larger business may not be appropriate, or even feasible, in smaller organizations given their size and funding restrictions. For example, most small businesses will not be able to afford the luxury of hiring ethics officers or ethics counselors to train and counsel employees, as well as institutionalize and monitor a healthy ethical context. Therefore, small business managers must instead employ pragmatic, cost-effective strategies to manage the ethical context and immediately arrest aversive/malevolent behaviors when they arise, which can include the identification of such behavior, followed by some form of punishment. Employees must understand that uncivil behaviors are not tolerated in the workplace, and that a no-tolerance policy exists that will severely damage perpetrator standing in the organization. Indeed, the scant ethics literature dealing with transforming the small business ethical environment suggests that codes of ethics may be ineffective, a contention partially supported by our findings, in deference to strong ethical leadership at the top (Jenkins 2006; Spence and Lozano 2000; Vitell et al. 2000). Specifically, the literature suggests that what is potentially more important than the presence of a written code of ethics, which in many organizations is a mere formality or “window dressing,” is that organizational employees are aware that the business conducts itself with moral integrity, and that they also believe in the business’s generalized morality themselves (Jenkins 2006; Spence and Lozano 2000); positive ethical leadership is imperative (Fernández and Camacho 2016). Further, the authors underscore the importance of small business internal relations spearheaded by strong moral leadership. In sum, small business ethical environments will only improve when leadership takes an uncompromising stance that clearly communicates that misbehaviors will not be tolerated, and will be severely punished, while ethical and related helping behaviors will be instead supported and rewarded (Vitell et al. 2000).

Despite the fact that the above small business literature downplays the importance of a written code of ethics, our findings suggest that such a code is nevertheless important for enhancing employee ethical reasoning (see Fernández and Camacho 2016) and precipitating an internal locus of control, which are necessary to empower employees to take personal action to influence the ethical environment. To support employee grassroots ethical behavior, a small business will ideally promote an internal champion who will sponsor an environmental image branding of generalized morality that becomes institutionalized as “what the business does,” while also monitoring employee counterproductive tendencies that can harm ethical reasoning (Jenkins 2006, p. 253). Unfortunately, the converse will also be true, meaning that if leadership instead displays social aversion/malevolence, there is little hope that the small business will be able to cleanse itself of negative behavioral norms and incivility.

Finally, there is support in the small business ethics literature that employees prefer to learn about ethics by networking with their peers, often at small business conferences (Jenkins 2006; Fassin et al. 2011). The authors also identify that small business owners are often greatly influenced by pragmatic aspects of the popular business press. Based on this literature, a potential strategy to influence leadership about ethical considerations is to provide topics at small business conferences that deal with the importance of establishing an ethical environment. Specific conference topics could also include training and role-playing activities that demonstrate how to eradicate such incivility in the workplace.

Contributions, Limitations, and Suggestions for Future Research

This study contributes to the scant literature dealing with ethics in smaller organizations, particularly in relation to the “Malicious Two” (Volmer et al. 2016, p. 414). Specifically, the findings suggest that the presence of a code of ethics is helpful to promote small business ethical reasoning and internal locus of control, which can develop the ethical context. In contrast, the study also contributes to the literature by demonstrating that aversive/malevolent behaviors compromise small business employee ethical reasoning. The presence of an ethics code is insufficient to arrest aversion/malevolence behaviors, so leadership should strategize to eradicate such behaviors by taking a firm stance against dark behaviors by setting an ethical “tone at the top.” Leadership should also consider requiring all personnel to attend small business conferences that present strategies to minimize dark behaviors and promote generalized morality.

While the study makes a number of significant contributions to the small business/entrepreneurial ethics literature, we do note some limitations of the study. For example, we do not intend to make inferences of causality due to the cross-sectional nature of the study. Further, there may be self-selection bias due to the possibility that study subjects who volunteered to participate are more altruistic than most business professionals. We also caution against extending the findings to other business fields because our sample contained only employees working for organizations with 100 or fewer employees, and most were employed broadly speaking as sales professionals. Furthermore, given that some data were obtained from a national sample of sales professionals, nonresponse bias could be a problem, but tests of early versus later respondents suggested that this form of bias was not a concern. The study also addressed sensitive issues relating to aversion/malevolence behaviors, so this likely compromised our response rate in the national sample and also could have led some participants to provide socially acceptable answers, so we controlled for social desirability bias in our models tested. We also used parts of scales to measure some constructs, a common practice that should be employed with caution because scale reliability can be potentially compromised. We assessed the reliability, dimensionality, and validity of our constructs and concluded that they appear to be reasonably stable. Finally, the study assessed a highly sensitive topic, so we had difficulty collecting data from a national sample in isolation because of a relatively small sample size. Because of the importance of assessing aversion/malevolence in the small business context, we opted to augment our national sample data with a targeted convenience sample of selling professionals. Use of a nonprobability sample is not ideal, yet we deemed it necessary to obtain necessary sample size and statistical power. Therefore, we encourage readers to interpret our findings with caution given that point estimates may lack precision.

Our findings answer a number of questions regarding ethics in the small business and entrepreneurial venture context; however, numerous unexplored questions remain. Future research should investigate whether active communication of the code of ethics arrests aversive/malevolent behaviors, despite our finding that the presence of an ethics code was not successful in mitigating such dark behaviors. Future research should also investigate, on a pre- versus post-longitudinal basis, the effectiveness of having employees attend small business conferences that deal with strategies to minimize uncivil behaviors. This study could specifically investigate whether employee ethical reasoning is subsequently enhanced. Finally, future research should investigate any appropriate strategies that may be used to effectively transform the aversive/malevolent tendencies exhibited by small business leaders.

References

Adams, J. S., Tashchian, A., & Shore, T. H. (2001). Codes of ethics as signals for ethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(3), 199–211.

Alexander, C. S., & Becker, H. J. (1978). The use of vignettes in survey research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 42(1), 93–104.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14, 396–402.

Ashkanasy, N. M., Windsor, C. A., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Bad apples in bad barrels revisited: Cognitive moral development, just world beliefs, rewards, and ethical decision-making. Business Ethics Quarterly, 16(4), 449–473.

Barnett, T. (2001). Dimensions of moral intensity and ethical decision-making: An empirical study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(5), 1038–1057.

Barnett, T., Bass, K., & Brown, G. (1994). Ethical ideology and ethical judgment regarding ethical issues in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(6), 469–480.

Bass, K., Barnett, T., & Brown, G. (1999). Individual difference variables, ethical judgments, and ethical behavioral intentions. Business Ethics Quarterly, 9(2), 183–205.

Boddy, C. R. (2014). Corporate psychopaths, conflict, employee affective well-being and counterproductive work behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(1), 107–121.

Boone, C., Brabander, B., & Witteloostuijn, A. (1996). CEO locus of control and small firm performance: An integrative framework and empirical test. Journal of Management Studies, 33(5), 667–700.

Brower, H. H., & Shrader, C. B. (2000). Moral reasoning and ethical climate: Not-for-profit vs. for-profit boards of directors. Journal of Business Ethics, 26(2), 147–167.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Bryant, P. (2009). Self-regulation and moral awareness among entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 505–518.

Christie, R., & Geis, F. L. (1970). Studies in Machiavellianism. New York: Academic Press.

Cohen, T. R., Panter, A. T., Turan, N., Morse, L., & Kim, Y. (2014). Moral character in the workplace. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 943.

Craft, J. L. (2013). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 221–259.

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1960). A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24(4), 349–354.

Darrat, M., Amyx, D., & Bennett, R. (2010). An investigation into the effects on work-family conflict and job satisfaction on salesperson deviance. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 30, 239–251.

Dawson, S., Breen, J., & Satyen, L. (2002). The ethical outlook of micro business operators. Journal of Small Business Management, 40(4), 302–313.

Fassin, Y., Rossem, A. V., & Buelens, M. (2011). Small-business owner-managers’ perceptions of business ethics and CSR-related concepts. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(3), 425–453.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191.

Fernández, J. L., & Camacho, J. (2016). Effective elements to establish an ethical infrastructure: An exploratory study of SMEs in the Madrid region. Journal of Business Ethics, 138(1), 113–131.

Ferrell, O. C., & Gresham, L. G. (1985). A contingency framework for understanding ethical decision making in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 49(3), 87–96.

Ferrell, O. C., Johnston, M. W., & Ferrell, L. (2007). A framework for personal selling and sales management ethical decision making. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 27(4), 291–299.

Ferrell, O. C., & Skinner, S. J. (1988). Ethical behavior and bureaucratic structure in marketing research organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(1), 103–109.

Fischer, D. G., & Fick, C. (1993). Measuring social desirability: Short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53, 417–424.

Fisscher, O., Frenkel, D., Lurie, Y., & Nijhof, A. (2005). Stretching the frontiers: Exploring the relationships between entrepreneurship and ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 60(3), 207–209.

Forte, A. (2004). Business ethics: A study of the moral reasoning of selected business managers and the influence of organizational ethical climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 51(2), 167–173.

Gok, K., Sumanth, J. J., Bommer, W. H., Demirtas, O., Arslan, A., Eberhard, J., Ozdemir, A. I., & Yigit, A. (2017). You may reap what you sow: How employees’ moral awareness minimizes ethical leadership’s positive impact on workplace deviance. Journal of Business Ethics, 146(2), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3655-7.

Hannafey, F. T. (2003). Entrepreneurship and ethics: A literature review. Journal of Business Ethics, 46(2), 99–110.

Harris, J. D., Sapienza, H. J., & Bowie, N. E. (2009). Ethics and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 407–418.

Hunt, S. D., & Vasquez-Parraga, A. Z. (1993). Organizational consequences, marketing ethics, and salesforce satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 21(1), 78–90.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. J. (2006). A general theory of marketing ethics: A revision and three questions. Journal of Macromarketing, 26(2), 143–153.

Jackson, R. W., Wood, C. M., & Zboja, J. J. (2013). The dissolution of ethical decision-making in organizations: A comprehensive review and model. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(2), 233–250.

Jelinek, R., & Ahearne, M. (2006). The enemy within: Salesperson deviance and its determinants. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 26(2), 327–344.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Small business champions for corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(3), 241–256.

Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2010). Different provocations trigger aggression in narcissists and psychopaths. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1(1), 12–18.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision-making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395.

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80–92.

Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2002). Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy indicators of a common core construct?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(3), 693–710.

Kaptein, M. (2009). Ethics programs and ethical culture: A next step in unraveling their multi-faceted relationship. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(2), 261–281.

Kaptein, M., & Schwartz, M. S. (2008). The effectiveness of business codes: A critical examination of existing studies and the development of an integrated research model. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(2), 111–127.

Khan, S. A., Tang, J., & Zhu, R. (2013). The impact of environmental, firm, and relational factors of entrepreneurs’ ethically suspect behaviors. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(4), 637–657.

Kim, G. S., Lee, G. Y., & Park, K. (2010). A cross-national investigation on how ethical consumers build loyalty toward fair trade brands. Journal of Business Ethics, 96, 589–611.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Treviño, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 1–31.

Klotz, A. C., & Neubaum, D. O. (2016). Research on the dark side of personality traits in entrepreneurship: Observations from an organizational behavior perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(1), 7–17.

Levenson, M. R., Kiehl, K. A., & Fitzpatrick, C. M. (1995). Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(1), 151–158.

Loe, T. W., Ferrell, L., & Mansfield, P. (2000). A review of empirical studies assessing ethical decision making in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 25(3), 185–204.

Longenecker, J. G., McKinney, J. A., & Moore, C. W. (1989). Ethics in small business. Journal of Small Business Management, 27(1), 27–31.

Longenecker, J. G., Moore, C. W., Petty, J. W., Palich, L. E., & McKinney, J. A. (2006). Ethical attitudes in small businesses and large corporations: Theory and empirical findings from a tracking study spanning three decades. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(2), 167–183.

Longenecker, J. G., & Schoen, J. E. (1975). The essence of entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management, 16(3), 1–6.

Lumpkin, J. R. (1985). Validity of a brief locus of control scale for survey research. Psychological Reports, 57(2), 655–659.

Lumpkin, J. R., & Hunt, J. B. (1989). Mobility as an influence of retail patronage behavior of the elderly: Testing conventional wisdom. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 17(Winter), 1–12.

Mayo, M. A., & Marks, L. J. (1990). An empirical investigation of a general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 18(2), 163–171.

McCabe, D. L., Treviño, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (1996). The influence of collegiate and corporate codes of conduct on ethics-related behavior in the workplace. Business Ethics Quarterly, 6(4), 461–476.

McClaren, N. (2015). The methodology in empirical sales ethics research: 1980–2010. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(1), 121–147.

McDonald, G. M., & Zepp, R. A. (1990). What should be done? A practical approach to business ethics. Management Decision, 28(1), 9–14.

McKinney, J. A., Emerson, T. L., & Neubert, M. J. (2010). The effects of ethical codes on ethical perceptions of actions toward stakeholders. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(4), 505–516.

Miller, D. (2014). A downside to the entrepreneurial personality. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(1), 1–8.

Miller, D., De Vries, M. F. R. K., & Toulouse, J. M. (1982). Top executive locus of control and its relationship to strategy-making, structure, and environment. Academy of Management Journal, 25(2), 237–253.

Morris, M. H., Schindehutte, M., Walton, J., & Allen, J. (2002). The ethical context of entrepreneurship: Proposing and testing a developmental framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 40(4), 331–361.

O’Boyle, E. H. Jr., Forsyth, D. R., Banks, G. C., & McDaniel, M. A. (2012). A meta-analysis of the dark triad and work behavior: A social exchange perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 557.

O’Fallon, M. J., & Butterfield, K. D. (2005). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 1996–2003. Journal of Business Ethics, 59(4), 375–413.

Pandey, J., & Tewary, N. B. (1979). Locus of control and achievement values of entrepreneurs. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 52(2), 107–111.

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563.

Pearce, I. I., J. A (2013). Using social identity theory to predict managers’ emphases on ethical and legal values in judging business issues. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(3), 497–514.

Randall, D. M., & Fernandes, M. F. (1991). The social desirability response bias in ethics research. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(11), 805–817.

Randall, D. M., & Gibson, A. M. (1990). Methodology in business ethics research: A review and critical assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(6), 457–471.

Rauthmann, J. F., & Kolar, G. P. (2013). The perceived attractiveness and traits of the dark triad: Narcissists are perceived as hot, Machiavellians and psychopaths not. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(5), 582–586.

Reidenbach, R. E., & Robin, D. P. (1988). Some initial steps toward improving the measurement of ethical evaluations of marketing activities. Journal of Business Ethics, 7(11), 871–879.

Reidenbach, R. E., & Robin, D. P. (1990). Toward the development of a multidimensional scale for improving evaluations of business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(8), 639–653.

Rest, J. R. (1986). Moral development: Advances in research and theory. New York: Praeger.

Rhodewalt, F., & Peterson, B. (2009). Narcissism. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle. (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 547–560). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Robertson, D. C. (1991). Corporate ethics programs: The impact of firm size. In B. Harvey, H. van Luijk & G. Corbetta. (Eds.), Market morality and company size (pp. 119–136). Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Roof, R. (2015). The association of individual spirituality on employee engagement: The spirit at work. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(3), 585–599.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal and external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28.

Rotter, J. B. (1990). Internal versus external control of reinforcement: A case history of a variable. American Psychologist, 45(4), 489–493.

Ruiz, P., Martinez, R., Rodrigo, J., & Diaz, C. (2015). Level of coherence among ethics program components and its impact on ethical intent. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(4), 725–742.

Schjoedt, L., & Shaver, K. G. (2012). Development and validation of a locus of control scale for the entrepreneurship domain. Small Business Economics, 39(3), 713–726.

Schonlau, M., Ronald, D. Jr., & Elliott, M. N. (2002). Conducting research surveys via email and the web (Appendix C). Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Schwartz, M. (2001). The nature of the relationship between corporate codes of ethics and behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 32(3), 247–262.

Singh, J. B. (2006). A comparison of the contents of the codes of ethics of Canada’s largest corporations in 1992 and 2003. Journal of Business Ethics, 64(1), 17–29.

Spector, P. E. (1988). Development of the Work Locus of Control Scale. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 61(4), 335–340.

Spence, L. J., & Lozano J. F. (2000). Communicating about ethics with small firms: Experiences from the U.K. and Spain. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(1), 43–53.