Abstract

Although a growing body of research has shown the positive impact of ethical leadership on workplace deviance, questions remain as to whether its benefits are consistent across all situations. In this investigation, we explore an important boundary condition of ethical leadership by exploring how employees’ moral awareness may lessen the need for ethical leadership. Drawing on substitutes for leadership theory, we suggest that when individuals already possess a heightened level of moral awareness, ethical leadership’s role in reducing deviant actions may be reduced. However, when individuals lack this strong moral disposition, ethical leadership may be instrumental in inspiring them to reduce their deviant actions. To enhance the external validity and generalizability of our findings, the current research used two large field samples of working professionals in both Turkey and the USA. Results suggest that ethical leadership’s positive influence on workplace deviance is dependent upon the individual’s moral awareness—helpful for those employees whose moral awareness is low, but not high. Thus, our investigation helps to build theory around the contingencies of ethical leadership and the specific audience for whom it may be more (or less) influential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, ethical leadership (cf. Brown et al. 2005; Brown and Treviño 2006) has become a “hot topic” in the popular press, fueled in large part by the significant number of ethical scandals that have negatively impacted the global economy since the early 2000s. During this time, Enron, Tyco, WorldCom, Arthur Andersen, Wells Fargo, Volkswagen and Bernie Madoff, to name just a few, have become infamous household names, synonymous with egregious unethical and illegal behavior.

This heightened interest and focus on ethical leadership (and the lack thereof) is similarly reflected in the academic literature. In their recent meta-analysis exploring the antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership, Bedi and colleagues (2016) identified 134 independent samples and nearly 55,000 employees that have taken part in this growing research stream, serving to highlight the significant time and energy scholars have invested in trying to understand ethical leadership’s role within organizations. Although leaders’ high-profile actions typically garner most of the headlines and claim a significant portion of scholars’ attention, employees’ (un)ethical behaviors have also come under greater empirical scrutiny. Since the early days of the ethical behavior literature, when most investigations focused exclusively on identifying the drivers of positive forms of employee behavior (e.g., organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) and prosocial behavior), scholars have broadened and expanded their focus to also include the “dark side” of employee behavior (e.g., employee deviance and counterproductive work behaviors or CWBs). This subtle, but important shift has been motivated, in part, by a recognition of the significant costs unethical behavior poses to industry, including shrinkage due to employee theft, reduced productivity from abusive treatment and negative publicity and its harmful impact upon key stakeholders (Bennett and Robinson 2000; Tepper et al. 2008; van Gils et al. 2015).

Given the significant problem workplace deviance poses to organizational effectiveness, scholars have sought to find empirically driven remedies and, for valid reasons, have touted ethical leadership as one of the most effective solutions to this widespread and ongoing problem (Brown and Treviño 2006; Den Hartog 2015; Treviño et al. 2014). In fact, recent meta-analytic work by Hoch et al. (2016) establishes ethical leadership as a useful remedy to the problem of employee deviance, above and beyond other leadership styles (e.g., transformational, authentic and servant leadership). Furthermore, many organizational scholars have continued to theorize about the benefits of ethical leadership, further reinforcing the idea that ethical leadership is useful across almost all situations (for recent reviews, please see Bedi et al. 2016; Den Hartog 2015; Hoch et al. 2016; Ng and Feldman 2015; Treviño et al. 2014).

Despite this recognition of ethical leadership as a powerful contextual lever to effect positive change, emerging research suggests that a more nuanced and conditional view of ethical leadership’s role may be more accurate. In recent years, studies have begun to show that the direct influence of ethical leadership may be less impactful across certain contexts (cf. Avey et al. 2011; Chuang and Chiu 2017; Kalshoven et al. 2013; Taylor and Pattie 2014). Additionally, long-standing theoretical perspectives suggest that substitutes for leadership frequently exist (Kerr and Jermier 1978), serving to eliminate the need for strong leadership across all situations (Babalola et al. 2017). Taken together, this research suggests that despite the considerable evidence supporting ethical leadership as a powerful deterrent against employee deviance (Avey et al. 2011; Mayer et al. 2009); the positive impact of ethical leadership may be conditional and dependent upon other important factors, such as followers’ moral characteristics. We base this argument on emerging research highlighting the role of individuals’ moral dispositions as a critical influence on how they respond to strong expressions of ethical leadership (Babalola et al. 2017; Chuang and Chiu 2017; Kalshoven et al. 2013; Sturm 2017).

To add to this growing body of work, we highlight here the role of individuals’ moral awareness (Reynolds 2006) as an important boundary condition of ethical leadership. By identifying this contingency, we not only help to add new insights and refine ethical leadership theory for scholarly use, but also provide managers with practical guidance about where to specifically target their expressions of ethical leadership (i.e., those low in moral awareness). As we will articulate in greater detail below, we suggest that for individuals who are already highly attuned to moral issues (i.e., possess a high level of moral awareness), having a leader who works hard to communicate and reinforce an ethics-first message may have little effect in lowering their deviant conduct. However, for individuals who lack this heightened level of moral understanding, ethical leadership may play a pivotal role in helping them see the importance of acting in an ethical manner and thus, motivate them to reduce their own deviant actions.

Through this investigation, we aim to make three important contributions to the literature. First, we seek to demonstrate how ethical leadership acts as a general deterrent against deviant employee behavior directed at both the organization and one’s supervisor. To do this, we utilize two, large field samples of working professionals in both Turkey and the USA, thus providing more generalizable, cross-cultural evidence for how ethical leadership functions. Second, we highlight an important, but to date, unexplored boundary condition of ethical leadership—individuals’ moral awareness—that should be accounted for when examining the impact of ethical leadership. Absent such a perspective, our findings suggest both scholars and practitioners alike may erroneously conclude that engaging in ethical leadership is always beneficial or necessary. Third, we provide leaders with practical insights about whom their acts of ethical leadership should target. By providing leaders with clearer guidance into the types of employees who are influenced most by their actions, we seek to help leaders save valuable time, energy and resources in their ongoing effort to lead others effectively.

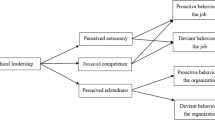

We begin by briefly reviewing prior research on workplace deviance and ethical leadership. Next, we discuss our hypothesis linking ethical leadership to workplace deviance, and how individuals’ moral awareness may moderate this relationship. We then utilize hierarchical moderated regression analysis to test our hypothesized model across two large field samples of employees in both Turkey and the USA. Finally, we discuss the implications of our findings for both theory and practice, acknowledge study limitations and offer avenues for future research. Figure 1 depicts our hypothesized relationships.

Literature Review

Workplace Deviance

Acts of workplace deviance may be characterized as sins of commission, as opposed to sins of omission, in that they are voluntary behaviors intended to violate organizational norms and harm organizational functioning (Bennett and Robinson 2000; Robinson and Bennett 1995). Whether it involves stealing from people and/or the organization, damaging company property, arriving late to work, taking unauthorized breaks, neglecting to follow instructions, publicly embarrassing one’s supervisor, sharing confidential company information, gossiping or even violence (Bennett and Robinson 2000; Berry et al. 2007; Ferris et al. 2009; Vardi and Wiener 1996), workplace deviance is typically seen as egregious, willful behavior.

Although conceptualizations of workplace deviance have varied over the years (Bennett and Robinson 2000; Robinson and Bennett 1995), the deviance literature has begun to distinguish between two primary targets when individuals attempt to retaliate against perceived workplace injustices—organization-directed deviance and supervisor-directed deviance (Hershcovis et al. 2007; Mitchell and Ambrose 2007). These two forms of counterproductive seem to be driven by individuals’ motivations and ability to retaliate. When individuals perceive their supervisor has treated them unfairly, research suggests they may be more likely to engage in supervisor-directed deviance that is intended to undermine, ridicule or challenge their bosses (Baron and Neuman 1998; Bies and Tripp 1998). Thus, supervisor-directed deviance is borne of employees’ sense of direct violation at the hands of their supervisor(s). However, displaced aggression theory (Dollard et al. 1939) and subsequent empirical work (Mitchell and Ambrose 2007) also suggest that negative forms of leadership and/or supervision may encourage actors to engage in deviance directed toward the organization (i.e., organizational-directed deviance). When individuals fear further retaliation at the hands of their perpetrator, or are limited in their ability to retaliate directly against him/her, this displaced form of aggression toward the organization may be the chosen retaliatory avenue (Dollard et al. 1939). Thus, both supervisor-directed and organization-directed deviance may be appropriate targets for individuals to express their displeasure with their leader(s).

Extant research has also documented many underlying motives driving individuals’ deviant conduct. While some scholars have proposed that individuals may engage in deviant behavior, simply to experience the thrill of rebelling against authority (Bennett and Robinson 2000), in most cases, research points to workplace deviance stemming from perceived injustices, dissatisfaction, poor role modeling and mistreatment at the hands of one’s leader (cf. Tepper et al. 2009). Research also suggests that both contextual and individual factors are associated with employees’ deviant conduct. Contextual factors may include a hostile work climate (Mawritz et al. 2012), psychological contract breaches (Bordia et al. 2008), abusive supervision (Tepper et al. 2008, 2009; Mitchell and Ambrose 2007; Martinko et al. 2013) and workplace aggression (Hershcovis and Barling 2010), while individual factors may include negative emotions and a desire for revenge (El Akremi et al. 2010). Together, these factors make a compelling argument for considering both the person and the context simultaneously (Treviño 1986) when trying to predict whether individuals will engage in deviant actions.

Ethical Leadership

At its core, leadership is about positively influencing others (Hannah et al. 2014; Yukl 2002). Treviño et al. (2014) postulated that leaders play a key role as authority figures and role models and have sizable influence on subordinates’ attitudes and behaviors. Ethical leadership, by the way of its explicit moral focus, explains how leaders, through their ethical conduct, can positively influence those around them in the pursuit of broader organizational goals and objectives (Brown et al. 2005; Sumanth and Hannah 2014).

Ethical leadership is defined as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (Brown et al. 2005: 120). It is based on the view that ethical conduct is a central aspect of leadership and encompasses the whole person, not just ancillary dimensions (Mayer et al. 2009). For this reason, Brown et al. (2005) described ethical leadership as including both trait (i.e., the moral person) and behavior (i.e., the moral manager) dimensions. They argued that ethical leadership can be reflected by leader traits such as integrity, social responsibility, fairness and the willingness to think through the consequences of one’s actions. At the same time, ethical leadership is also reflected by specific behaviors, through which the leader promotes workplace ethicality. Drawing from social learning theory (Bandura 1986), ethical leadership involves influencing individuals to engage in ethical behaviors through behavioral modeling of transactional leadership behaviors (e.g., rewarding, communicating and punishing). In this way, ethical leadership is based on the belief that ethics represent a critical component of effective leadership and leaders are responsible for promoting ethical climates and behavior (Brown and Treviño 2006). This behavioral aspect is particularly important when it comes to understanding the cascading effects of leader behavior.

The accumulated evidence suggests that ethical leadership is positively associated with numerous workplace benefits. Whether it be improved employee attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction, affective commitment and work engagement), reduced turnover intentions (Brown et al. 2005; Kim and Brymer 2011, Neubert et al. 2009; Ruiz et al. 2011; Tanner et al. 2010), heightened citizenship behavior (Avey et al. 2011; Kacmar et al. 2011; Piccolo et al. 2010), increased voice (Brown and Treviño 2006; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009), enhanced job performance (Ahn et al. 2016; Piccolo et al. 2010; Walumbwa et al. 2011) or reduced deviance and unethical behavior at work (Mayer et al. 2009, 2012), ethical leadership has been shown to drive a host of desirable outcomes.

Hypothesis Development

Ethical Leadership and Workplace Deviance

To better understand the many benefits of ethical leadership, scholars have looked to theories of social learning (Bandura 1986) and social exchange (Blau 1964) as the psychological mechanisms through which ethical leadership may operate. To date, this work has offered three useful explanations—(a) leaders’ role modeling, (b) leaders’ effects on individuals’ attitudes and behaviors and (c) social exchange/reciprocity norms of behavior—each of which we describe below.

First, social learning theory posits that individuals look to their social environment for cues as to the kinds of behaviors that are expected, rewarded and punished (Bandura 1986; Brown et al. 2005). Although individuals may behave and learn through their own volition and self-influence (Johns and Saks 2014), social learning theory asserts that individuals primarily learn through observing others’ behavior and the consequences such behavior elicits (Davis and Luthans 1980). In many cases, individuals learn what constitutes normative behavior from their leaders. Through a process of social learning and observation, individuals learn their leaders’ values and norms concerning ethical conduct and how to respond to moral issues at work (Avolio et al. 2004; Sims and Brinkman 2002). In fact, research finds that leaders who act in unethical ways can increase the likelihood that their employees will engage in counterproductive work behaviors (CWB) such as theft, sabotage, withdrawal and production deviance (Bennett and Robinson 2000; Ferris et al. 2009; Tepper et al. 2009). Numerous studies have also shown that a leader’s ethical behavior has a cascading effect on employees lower in the organizational hierarchy through the mechanisms of social learning and role modeling (Brown and Treviño 2006; Mayer et al. 2009; Schaubroeck et al. 2012).

Alternately, when leaders consistently demonstrate high levels of integrity, they earn a reputation for being credible and trustworthy sources of information and guidance (Brown and Treviño 2006; Kouzes and Posner 2011). This reputation, in turn, helps to build employees’ sense of confidence in and commitment to their leaders and organizations (Ng and Feldman 2015). Such leaders are perceived as positive role models that individuals look up to, respect and model their behavior after (Bryan and Test 1967; Mayer et al. 2010; Piccolo et al. 2010). Research also finds that leaders who possess high moral character and consistently uphold ethical principles are more likely to be emulated by subordinates (Mayer et al. 2012; Schaubroeck et al. 2012; Schminke et al. 2005) and rated by them as ethical leaders (Brown and Treviño 2014). Thus, leaders who consistently engage in ethical behaviors can serve as powerful moral examples for their employees.

Ethical leaders may also be able to prevent their employees from engaging in deviant workplace actions by improving their employees’ workplace attitudes (Treviño and Brown 2005; van den Akker et al. 2009). When leaders demonstrate consideration, support and trust in their employees, employees tend to exhibit more favorable attitudes and behaviors about their leaders and their workplace environment (Chullen et al. 2010). These positive emotions, attitudes and beliefs employees have about their leader(s) help to foster a stronger sense of attachment to the organization (Brown and Treviño 2006; Neves and Story 2015; Schminke et al. 2005). Importantly, these improved employee opinions of the leader help to reduce incidents of workplace misconduct. When employees experience ethical leadership, they tend to have greater affective commitment, which serves to reduce their organizational deviance, particularly when their supervisor has a reputation as a high performer (Neves and Story 2015). Thus, leaders who serve as strong ethical role models and demonstrate high levels of competence can reduce the frequency of workplace deviance by strengthening employees’ attitudes, commitment and willingness to trust those in positions of authority.

Employees may also be motivated to engage in less deviant behavior because of a desire to reciprocate and give back to their leaders in positive ways. One of the most widely applied theories to issues of organizational life over the last 50 years (cf. Dulebohn et al. 2012), social exchange theory postulates that individuals follow a norm of reciprocity that obligates them to respond in kind (Blau 1964; Homans 1961; Thibaut and Walker 1975). Research shows that when leaders act in considerate ways toward their employees, employees respond by engaging in more frequent citizenship behaviors such as voicing helpful ideas for organizational improvement (Wang et al. 2005; Van Dyne et al. 2008).

However, social exchange can also operate in negative ways, encouraging more destructive forms of reciprocity. When leaders operate at the low end of the ethical leadership spectrum, they foster employee perceptions of suspicion, distrust and discomfort that may give rise to unethical follower conduct (Brown and Treviño 2004; Tepper et al. 2009; Thau et al. 2009). When leaders consistently and intentionally act in ways that demean, denigrate and disparage those around them, individuals are more apt to retaliate to try and “get even” (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005; Gouldner 1960). This suggests that leaders who engage in unethical behaviors create a context that encourages negative reciprocity where employees imitate the unethical conduct they see exhibited toward them (Treviño and Brown 2004; Brown and Mitchell 2010). Thus, while high ethical leadership motivates followers to reciprocate with moral behavior, low ethical leadership motivates followers to display negative behavior, either through modeling, breaches in the exchange relationships, or reduced identification (van Gils et al. 2015, p. 3).

In addition to the different ways in which employees may respond to acts of (un)ethical leadership, the target of employees’ retaliation (i.e., organization vs. supervisor) may also vary. When employees feel powerless and incapable of effecting meaningful change with their supervisor directly, employees may decide to direct their aggression more broadly toward the organization, rather than their leaders (Tepper et al. 2009; Xu et al. 2012; Schyns and Schilling 2013). Supporting this view, Hershcovis and Barling (2010) found that supervisors’ aggression resulted in not only negative employee attitudes (e.g., lower job satisfaction, lower affective commitment and increased turnover intention), but also high levels of deviance directed at the organization. This is because retaliating directly against one’s supervisor can be dangerous and threatening to one’s career and has the potential to backfire on the deviant actor (Rehg et al. 2008; Sumanth et al. 2011). For this reason, employees may choose retaliation against the organization (e.g., engaging in deviant work behavior, withholding and reducing effort, failing to be a good corporate citizen), deeming it a safer way to get even with their leaders.

In other cases, employees may choose to retaliate directly against their supervisors. When leaders act in abusive ways toward employees who are already intent on leaving the organization, supervisor-directed deviance is more likely (Tepper et al. 2009). Other studies also support the view that negative leader behaviors serve as a powerful trigger for supervisor-directed deviance (e.g., Mitchell and Ambrose 2007; Tepper et al. 2008). In their meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes, Schyns and Schilling (2013) reported strong, positive correlations between destructive leadership and employees’ counterproductive work behavior directed specifically at the leader. These findings suggest that although employees may choose subtler means of retaliating against their supervisor’s unethical conduct (i.e., directing deviance at the organization), in situations where employees perceive a strong and direct injustice perpetrated against them by their supervisor, employees may be more likely to retaliate directly against their supervisors.

In sum, this evidence suggests that both high and low levels of ethical leadership will directly influence how employees respond attitudinally and behaviorally toward their supervisors and organizations (Brown and Treviño 2006; Mayer et al. 2009). Through a combination of both social learning and social exchange motives, individuals may engage in more productive organizational actions when supported by a leader who consistently exhibits ethical leadership behaviors. Conversely, low levels of ethical leadership may have the opposite effect on employees and encourage them to retaliate against their organizations and supervisors to restore a sense of justice and equity to the relationship. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a

Ethical leadership will be negatively associated with employees’ deviance directed at the organization.

Hypothesis 1b

Ethical leadership will be negatively associated with employees’ deviance directed at the supervisor.

The Moderating Role of Moral Awareness

Our initial hypothesis that ethical leadership will be associated with lower levels of deviance directed at both the organization and supervisor is hardly provocative and has been widely supported in prior research. The identification of situations where ethical leadership may not be relevant, or its consequences largely mitigated, however, offers scholars and practitioners something different and interesting to consider.

Moral awareness is “a person’s determination that a situation contains moral content and legitimately can be considered from a moral point of view” (Reynolds 2006: 233). In other words, moral awareness is the disposition of some people to recognize situations that are likely to cause moral wrong or harm to individuals and entities (VanSandt et al. 2006). For this reason, moral awareness is an important feature of individuals’ moral reasoning and moral decision making (Rest 1986) and serves as a precursor to their incorporation of moral elements into situational judgments.

In a leadership context, we assert that employees who have a high moral awareness will be less influenced by their leader’s ethical behavior than employees who do not already possess high moral awareness. In this way, moral awareness behaves as a substitute for ethical leadership, consistent with the substitutes for leadership framework (Kerr and Jermier 1978) originally put forth as an extension of House’s path-goal theory (House 1971). Kerr and Jermier (1978, p. 395) defined leadership substitutes as “a person or thing acting or used in place of another… [that] render(s)…leadership not only impossible but also unnecessary.” In other words, “a substitute is someone or something in the leader’s environment that reduces the leader’s ability to influence subordinate attitudes, perceptions, or behaviors, and, in effect, replaces the impact of his or her behavior” (Podsakoff et al. 1993, p. 2).

In the case of ethical leadership, the leader’s behavior is important because of the ethical model being displayed to the employee. This model is then followed by the employee based on social learning theory (Bandura 1986). In cases where an employee’s moral awareness is already high, however, the leader’s ethical model will be largely redundant and only serve to reinforce the employee’s existing beliefs. However, when an employee’s moral awareness is low, a different response is likely. In such instances, the leader’s (un)ethical behavior serves as the employee’s primary ethical cue and model for ethical action. Consequently, we would expect individuals with low moral awareness to follow their leader’s ethical example much more closely than those who have a high level of moral awareness, since the latter already possess a strong moral foundation for making ethical judgments. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2a

Employees’ moral awareness will moderate the negative relationship between ethical leadership and organization-directed deviance, such that the relationship will be more negative when employees’ moral awareness is low.

Hypothesis 2b

Employees’ moral awareness will moderate the negative relationship between ethical leadership and Supervisor-directed deviance, such that the relationship will be more negative when employees’ moral awareness is low.

Methods

In this section, we report the samples, procedures and measures used to operationalize and test the proposed theoretical model in Fig. 1. Further, we outline the procedures used to discriminate our model variables and test our hypotheses using both hierarchical regression analysis and the PROCESS macro.

Procedures and Samples

Procedures for Both Samples

To test our theoretical model, we collected multi-sourced, lagged field data from 772 working professionals in Turkey (Study 1) (n = 360) and the USA (Study 2) (n = 412). In both the Turkish and US samples, data were collected at two time periods (1 week apart) to minimize the likelihood of common method variance exerting undue influence on our results (Podsakoff et al. 2012). At Time 1, participants provided basic demographic information (e.g., age, gender, education and years of work experience) and ratings on the ethical leadership, moral awareness and honesty/humility measures. At Time 2, the same respondents were asked to provide measures of organization-directed deviance and supervisor-directed deviance.

To assist us in collecting the US sample data (Study 2), one of the researchers, who worked more than 10 years in the HVAC (heating, ventilation and air conditioning) industry as a manager of supply chain management, contacted his former employer to discuss the nature and purpose of the study. This led to the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the HVAC company’s human resources manager and two of the researchers. The MOU was signed to ensure that the study team would not disclose the company’s name in any resulting publications and that survey participants’ identities would remain confidential. With this confidentiality agreement in place, the HVAC manufacturer gave the research team permission to distribute and collect surveys at the company’s site in the Midwestern United States.

During the data collection process, we implemented several procedures to ensure anonymity and data confidentiality of all US study participants, particularly since we used both paper/pencil and online surveysFootnote 1 to gather our data. First, before administering any surveys, we informed participants about the voluntary nature of the study and assured them that their responses would be treated confidentially. Moreover, study participants were advised that all identifying information would be removed to preserve anonymity. Second, all paper/pencil survey recipients were given a return envelope for their survey so that none of their colleagues (e.g., supervisors) would see their responses. Participants were instructed to drop off their completed survey in a sealed envelope at one of two box locations—(a) the participants’ HVAC organization or (b) the home institution of the lead researcher.

To ensure we could link participants’ anonymous survey responses across two time periods, each participant was given two raffle tickets that had the same, 6-digit random number. During the first wave of data collection (i.e., Time 1), participants were instructed to staple one of the raffle tickets to their questionnaire upon completion. Participants were asked to save the second raffle ticket and staple it to the second questionnaire upon completing it at Time 2. This anonymous matching process enabled us to match 274 completed surveys from participants who completed the two paper/pencil questionnaires. To further strengthen and supplement this already robust sample, we also contacted a group of respondents via email and invited them to take our questionnaire via an anonymous, online survey tool. Online survey participants were instructed to make up a 6-digit identifier for themselves and to use it during both phases of data collection to facilitate survey matching. At the end of this process, we downloaded and matched 138 completed surveys from the online survey platform. In sum, by administering both paper/pencil and online surveys, our US data collection efforts yielded 412 completed, usable surveys.

We also implemented several procedures to ensure the anonymity of study participants and confidentiality of data collected in Turkey. Two members of the research team, who were invited as co-authors midway through the project, established contact with several human resources (HR) managers at various businesses and public institutions in a regional business and industrial hub located in central Turkey. These researchers explained the purpose and nature of the study to obtain HR managers’ support for their employees’ participation in the study. In addition, these researchers assisted in identifying a volunteer from each participating organization to distribute the data collection instruments (i.e., questionnaires, envelopes, two raffle tickets for survey matching) to their fellow employees. Using the same survey matching procedure that we used for the US sample, respondents were instructed to staple a raffle ticket with a preprinted six-digit random number to the questionnaire they completed at Time 1 and the second raffle ticket to the questionnaire they completed at Time 2. Respondents were then asked to place their completed questionnaires in a sealed envelope and drop it off in a researcher-provided box at their organization. Just as in Study 1, participants were also given the option to participate via an online survey tool. Those participants who chose to take the survey online were instructed to make up a 6-digit identifier and use it during both phases of data collection to facilitate the matching of surveys completed at Time 1 and Time 2.

Participants: Turkish Sample (Study 1)

Data for the first field study were obtained from a sample of working professionals in Turkey. Participants were selected using a convenience sampling approach to reach as many working professionals as possible in an industrial hub located in central Turkey. About a quarter of respondents had full-time employment at public organizations, while the rest were full-time employees working at small- and medium-sized enterprises in different industrial sectors, such as energy, retail, manufacturing, construction, financial services, information services and telecommunications. Of the 393 paper/pencil, and online questionnaires distributed during the first wave of data collection, researchers collected 349 paper/pencil surveys and 20 online surveys. One week later, during the second wave of data collection, 340 paper/pencil surveys were matched with the surveys from Time 1, along with all 20 online surveys. Thus, across the two waves of data collection, we matched a total of 360 questionnaires, yielding a 91.6% overall response rate. Of the 360 matched surveys, the majority (94.4%) of respondents completed paper/pencil surveys, while the remainder (5.6%) completed online surveys. To more conservatively estimate model parameters and other relevant statistics in our model, we used listwise deletion in SPSS to eliminate cases with missing data. This resulted in 339 observations being used to assess organization-directed deviance and 340 observations being used to assess supervisor-directed deviance.

Though only a small percentage of Study 1 participants completed online surveys, we nevertheless assessed whether responses to the four main study variables significantly differed between those participants who completed paper/pencil surveys and those who completed online surveys. Results from an independent two-samples test indicated that the mean difference between paper/pencil survey participants and online survey participants did not differ significantly from zero, since the 95% confidence intervals included zero for all four study variables. Thus, we combined responses from both the paper/pencil surveys (n = 340) and online surveys (n = 20) into a single sample for Study 1.

Our final combined Turkish sample was primarily male (66%), with an average age of 33.1 and 9.4 years of work experience. Three percent of participants were in upper management positions (e.g., Vice President, Chief Operating Officer and Chief Executive Officer), 10% in middle management, 18% in lower management, 43% in clerical/administrative roles and the rest (27%) in other positions. Participants’ educational levels varied significantly, with 27% having a high school diploma or equivalent, 16% possessing an associate’s degree, 43% having a bachelor’s degree and 8% holding a graduate degree.

Participants: US Sample (Study 2)

The US data were collected from three separate target groups, which together yielded a sample of 412 respondents. The first group of respondents consisted of 183 employees working for an HVAC manufacturing company in the Midwestern United States. Participants in this sample subset worked in assembly lines, specialized machine operations, engineering, finance, purchasing and quality control. The second group of respondents included 91 graduate business administration students from a small, public university in the Midwest who held part-time or full-time positions during the data collection process. Each respondent had at least 6 months of work experience at either manufacturing or service firms and worked in various jobs including assembly lines, specialized machine operations, customer service, finance, materials management and quality control. Students who voluntarily participated in both phases of the data collection process received course extra credit points as remuneration. The third and final group of respondents included 138 employees working in the Midwest who responded to our email request (sent to 200 individuals) to participate in our study. These respondents worked for various manufacturing companies in HVAC, aerospace, automobile and heavy equipment industries. Subjects in this group worked in specialized machine operations, engineering, accounting, finance, project management, purchasing and quality control. Unlike the first two groups of respondents who completed paper/pencil surveys, this third group of respondents only completed an anonymous, online survey.

Since our Study 2 sample of US working professionals came from three different participant sources, we considered whether participant group membership might influence our results and thus, should be included in subsequent analyses. We therefore conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess whether responses on our main study variables significantly differed across the three sample subsets (Lee et al. 2017). Results showed that the three groups did not significantly differ from one another at conventional significance levels (i.e., p < .05) on either of our predictors—moral awareness, F(2, 409) = 2.41, p = .09 or ethical leadership, F(2, 409) = 2.58, p = .08. Further, subsequent post hoc analyses of the pairwise comparison of group means showed that all three pairwise comparisons included zero in the 95% confidence intervals, providing further evidence that participant responses for moral awareness and ethical leadership did not significantly differ across the three participant groups of the sample. Results also revealed that there was no significant effect of group membership on participant responses to organization-directed deviance F(2, 409) = .90, p = .41 or supervisor-directed deviance, F(2, 409) = .02, p = .98. Given the results of this ANOVA and the lack of significant differences across the three subsets of samples on four main study variables, we chose to combine these participant groups into a single sample for Study 2.

Across the three participant groups, 523 survey requests were sent and 412 completed and usable questionnaires were returned (a 79% response rate). Once again, we used listwise deletion in SPSS to eliminate cases with missing data, resulting in 409 observations as our final sample size. Across this sample, participants were predominantly male (55%), averaged 31.2 years of age and possessed nearly 11.2 years of work experience. Less than 1% of participants held upper management positions, 9% were in middle management, 26% in lower management and 27% in administrative or clerical roles. The largest proportion of participants (38%) self-identified as operations workers, which included jobs operating specialized machinery and manual assembly work. The educational mix of participants included 66% with a high school diploma or equivalent, 30% with college degrees and 3% with graduate degrees.

Measures

Unless otherwise stated, all variables in both Study 1 and Study 2 were measured using a 5-point Likert agreement scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”). Table 1 provides scale reliabilities (i.e., Cronbach’s alphas) along the diagonal for measures used in the Turkish sample (Study 1), while Table 4 presents reliability estimates along the diagonal for the US sample (Study 2). Items comprising each scale were averaged to create composite measures for each variable, and items were coded such that higher scores equated to higher levels of the construct of interest.

Ethical leadership was measured using the ELS (Ethical Leadership Scale) developed by Brown et al. (2005). This scale consisted of ten items (e.g., “My supervisor disciplines employees who violate ethical standards”) (Study 1 α = .91; Study 2 α = .90).

Moral Awareness was measured using the three-item scale developed by Arnaud (2010) (e.g., “I am aware of ethical issues in this organization”) (Study 1 α = .83; Study 2 α = .67).

Organization-directed deviance was measured using Bennett and Robinson’s (2000) 12-item scale (e.g., “I spent too much time fantasizing or daydreaming instead of working”) (Study 1 α = .95; Study 2 α = .87). This variable was measured using a 5-point frequency scale where 1 = “Never” and 5 = “Very often.”

Supervisor-directed deviance was measured using Mitchell and Ambrose’s (2007) 10-item scale (e.g., “I gossiped about my supervisor”) (Study 1 α = .95; Study 2 α = .90). Like our measure of organization-directed deviance, this variable was measured using a 5-point frequency scale where 1 = “Never” and 5 = “Very often.”

Control Variables

We controlled for various demographic variables in our study, including the age, gender and work experience of participants. We chose these variables based on prior research showing significant relationships between these demographic characteristics and ethical issues. Research suggests moral awareness may covary with an individual’s age (Kohlberg 1981), just as ethical behavior may vary as a function of one’s expertise and knowledge accumulated over time (Ford and Richardson 1994; van Gils et al. 2015). Additionally, we controlled for individuals’ honesty and humility using Lee and Ashton’s (2004) 16-item measure (Study 1 α = .67; Study 2 α = .83), given the possibility that individuals who are more honest and humble may engage in less deviant behavior (Ashton et al. 2014; Zettler and Hilbig 2010). Thus, by including each of these variables in our model, we account for several alternative explanations that could challenge the validity of our findings (cf. Spector and Brannick 2011).

To provide initial evidence of construct validity, and consistent with prior recommendations from research (Bagozzi et al. 1991), we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of all survey items using AMOS version 22.0 with maximum likelihood estimation. To model the CFA, each item was fit to its latent factor (e.g., all supervisor-directed deviance items created a supervisor-directed deviance factor). After allowing residuals to correlate (cf. Cole et al., 2007), the expected four-factor solution displayed adequate fit across both studies: Study 1: (Chi-square [502] = 1516.38, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .078, SRMR = .056); Study 2: (Chi-square [466] = 1486.04, CFI = .88, RMSEA = .073, SRMR = .074). These adequate fit indices, combined with the results of our reliability analyses, provided robust support for the validity of our study measures across both samples.

Analytical Strategy

We employed various statistical techniques to examine the hypothesized relationships in our theoretical model (Fig. 1). We used hierarchical linear regression to test Hypotheses 1a and 1b, which proposed main effects of ethical leadership on both organization-directed deviance and supervisor-directed deviance. To examine these proposed main effects, we first included our control variables (age, gender work experience and honesty) in step 1 of the hierarchical regression analysis. In step 2, ethical leadership was entered along with the control variables. To test Hypotheses 2a and 2b, which proposed a moderating influence of moral awareness on ethical leadership, we used Hayes’ (2014) PROCESS macro (i.e., Model 1) and followed the procedures for regression analysis recommended by Aiken and West (1991), including mean centering the independent (ethical leadership) and moderator (moral awareness) variables. Following the approach recommended by Stone and Hollenbeck (1989) and Aiken and West (1991), we plotted the interactions at ±1 standard deviation above/below the mean to determine their form (see Figs. 2a, b, 3a, b).

Results

Study 1: Results (Turkey Sample)

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics, correlations and coefficient alphas for all Study 1 variables. Ethical leadership was positively associated with moral awareness (r = .20; p < .01), but negatively associated with organization-directed deviance (r = −.21; p < .01) and supervisor-directed deviance (r = −.16; p < .01). Correlational analysis also revealed a negative relationship between moral awareness and organization-directed deviance (r = −.18; p < .01) and supervisor-directed deviance (r = −.13; p < .05), and a positive relationship between moral awareness and honesty (r = .12; p < .05). Finally, age was significantly positively correlated with moral awareness (r = .09; p < .05) and work experience (r = .78; p < .01), while gender was positively correlated with honesty (r = .13; p < .05).

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1a predicted that ethical leadership would be negatively associated with employees’ deviance directed at the organization. Results from step 1 of the hierarchical regression analysis reveal that control variables (age, gender, work experience and honesty) accounted for only 5% of the variance in employees’ organization-directed deviance behavior, with honesty being the only significant predictor (β = .19; p ≤ .001). However, when added to these control variables, ethical leadership accounted for an additional 4% of the variance in employees’ organization-directed deviance behavior (see Table 2). Thus, since ethical leadership is a strong, negative predictor of organizational-directed deviance (β = −.22; p < .001), even after controlling for various factors, including individuals’ honesty (β = .20; p < .001), our results provide support for Hypothesis 1a.

Hypothesis 1b predicted that ethical leadership would be negatively associated with employees’ deviance directed at the supervisor. To evaluate the impact of ethical leadership on supervisor-directed deviance, we followed the same procedure as above, changing only the dependent variable in our regression model. Once again, honesty was the only significant predictor (β = .23; p < .001) of supervisor-directed deviance in step 1 of the hierarchical regression analysis, which explained 7% of the variance. After including ethical leadership in step 2, an additional 2% of the variance in supervisor-directed deviance was explained. Overall, these results show that ethical leadership is a significant negative predictor of supervisor-directed deviance (β = −.17; p ≤ .001), even after controlling for individuals’ honesty (β = .24; p < .001) and other demographic characteristics. Thus, Hypothesis 1b was also supported.

Hypothesis 2a predicted that employees’ moral awareness would moderate the negative relationship between ethical leadership and organization-directed deviance, such that the relationship would be more negative when employees’ moral awareness was low. As shown in Table 3, negative main effects of ethical leadership (β = −.14; p < .01) and moral awareness (β = −.19; p < .001) were found when predicting organizational-directed deviance. Importantly, the interaction term was significant for the moderating effect of moral awareness on organization-directed deviance (β = .22; p < .001). This significant interaction accounted for an additional 7% of the variance in organization-directed deviance, increasing from 9% in Hypothesis 1a to 16% in Hypothesis 2a.

Hypothesis 2b predicted that employees’ moral awareness would moderate the negative relationship between ethical leadership and supervisor-directed deviance, such that the relationship would be more negative when employees’ moral awareness was low. While there was a significant negative main effect of moral awareness on supervisor-directed deviance (β = −.17; p < .01), most importantly a significant interaction between ethical leadership and moral awareness was also found (β = .31; p < .001). This significant interaction term accounted for an additional 9% of the variance in supervisor-directed deviance, increasing from 9% in Hypothesis 1b to 18% in Hypothesis 2b.

Following the approach recommended by Stone and Hollenbeck (1989) and Aiken and West (1991), we plotted the interactions at ±1 standard deviation above/below the mean (see Fig. 2a, b). These graphs indicate that the highest levels of deviance (i.e., both organization-directed and supervisor-directed) were found at low levels of ethical leadership for those individuals who were also low in moral awareness.

Simple slopes analysis revealed that slopes were significantly different from zero for low levels of moral awareness when predicting both organization-directed (b = −.36, t = −5.12, p < .001) and supervisor-directed deviance (b = −.40, t = −5.49, p < .001). In contrast, the slope did not differ significantly from zero at high levels of moral awareness when predicting organization-directed deviance (b = .08, t = .95, p = .344), although it did differ from zero when predicting supervisor-directed deviance (b = .23, t = 2.485, p < .05). Taken together, this evidence suggests that the beneficial impact of ethical leadership to reduce individuals’ organization- and supervisor-directed deviance is strongest for those employees who rate low in moral awareness. Thus, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were both supported.

Although these findings provide robust preliminary support for our hypotheses and highlight the important role individuals’ moral awareness plays in driving the effects of ethical leadership, we sought to enhance the external validity of our findings by examining whether these effects held in a different national cultural context. For this reason, we sought to constructively replicate the findings from Study 1 with a different sample of working professionals in another country (the USA).

Study 2: Results (US Sample)

Table 4 provides descriptive statistics, correlations and coefficient alphas for all Study 2 variables. Results from this sample of US working professionals indicate that ethical leadership is negatively associated with moral awareness (r = −.09; p < .05), organization-directed deviance (r = −.18; p < .01), supervisor-directed deviance (r = −.21; p < .01), age (r = −.22; p < .01) and work experience (r = −.20; p < .01). We found that moral awareness was positively associated with honesty (r = .18; p < .01), age (r = .23; p < .01) and work experience (r = .23; p < .01) and that honesty was negatively associated with organization-directed deviance (r = −.31; p < .01), supervisor-directed deviance (r = −.16; p < .01) and gender (r = −.22; p < .01) but positively associated with age (r = .43; p < .01) and work experience (r = 39; p < .01). A significant negative association between organization-directed deviance and age (r = −.10; p < .05) was found but a positive one between gender and organization-directed deviance (r = .38; p < .01) and supervisor-directed deviance (r = .27; p < .01).

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1a predicted that ethical leadership would be negatively associated with employees’ deviance directed at the organization. Following the same analytical procedures as in Study 1, we entered the control variables (age, gender work experience and honesty) in Step 1 of the hierarchical regression model. Compared to Study 1, the control variables in Study 2 explained a significantly larger proportion of the variance (21%) in organization-directed deviance, including a significant main effect of gender (0 = female, 1 = male) (β = .33, p < .001) and a strong, negative effect of honesty (β = −.23, p < .001). Adding ethical leadership into the model in Step 2 increased the variance explained to 24%, suggesting ethical leadership (β = −.20, p < .001) accounted for an additional 3% of the variance after accounting for individuals’ honesty (β = −.23; p < .001). Thus, Hypothesis 1a was supported.

Hypothesis 1b predicted that ethical leadership would be negatively associated with employees’ deviance directed at their supervisor. Main effects of gender (β = .23, p < .001), work experience (β = .19, p = .05) and honesty (β = −.13, p < .05) were significant predictors of supervisor-directed deviance in Step 1 of the regression model, accounting for 9% of the variance in supervisor-directed deviance behavior. In Step 2, ethical leadership was added to the model, resulting in work experience no longer being a significant predictor of supervisor-directed deviance at conventional significance levels (β = .18, p = .058), while gender (β = .23, p < .001) and honesty (β = −.13, p < .05) remained significant. Adding ethical leadership (β = −.22, p < .001) in Step 2 contributed an additional 5% of the total variance, resulting in 14% of the total variance in employees’ supervisor-directed deviance behavior being explained by our model. Thus, Hypothesis 1b was also supported (Table 5).

Next, we examined the moderating role of moral awareness on the relationship between ethical leadership and organization-directed deviance (i.e., Hypothesis 2a). Once again, we used Hayes’ (2014) PROCESS macro (Model 1) and mean centered the independent and moderator variables (cf., Aiken & West 1991). As shown in Table 6, we found significant negative main effects of ethical leadership (β = −.16; p < .001), moral awareness (β = −.11; p < .01), honesty (β = −.24, p < .001) and gender (β = .35, p < .001) on organizational-directed deviance. Results also revealed a significant interaction between ethical leadership and moral awareness (β = .18, p < .01), which accounted for an additional 2% of the total variance in organizational-directed deviance.

Hypothesis 2b predicted that employees’ moral awareness would moderate the negative relationship between ethical leadership and supervisor-directed deviance, such that this relationship would be more negative when employees’ moral awareness was low. As shown in Table 6, we found significant negative main effects of ethical leadership (β = −.18; p < .001), honesty (β = −.15, p < .01) and gender (β = .25, p < .001). More importantly, our findings also uncovered a significant interaction between ethical leadership and moral awareness (β = .17, p < .01), which accounted for an additional 2% of the total model variance (15%).

Plotting these significant interactions at ±1 standard deviation above/below the mean (see Fig. 3a, b) revealed once again that the highest levels of deviance occurred at low levels of ethical leadership when individuals were low in moral awareness.

Analysis of simple slopes indicated that at low levels of moral awareness, the slope of the line differed significantly from zero when predicting both organization-directed deviance (b = −.34, t = −5.14, p < .001) and supervisor-directed deviance (b = −.34, t = −4.73, p < .001). However, the slope did not differ significantly from zero at high levels of moral awareness when predicting organization-directed deviance (b = .02, t = .31, p = .757) or supervisor-directed deviance (b = −.01, t = −.081, p = .935). This evidence again suggests that ethical leadership wields its benefits by reducing organization- and supervisor-directed deviance in those individuals whose moral awareness is low, not high. Thus, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were once again both supported.

Discussion

As organizations continue to seek solutions to ongoing ethical violations and deviant workplace behavior, understanding how leaders can help to minimize and eliminate such occurrences is of vital importance. To date, organizational scholars have presented ethical leadership as one potentially useful remedy to this problem, repeatedly arguing for its capacity to simultaneously enhance organizational functioning and reduce unethical workplace conduct (Brown and Treviño 2006; Mo and Shi 2017). Despite this recognition that ethical leadership has the potential to reduce the frequency of unethical acts, few studies have examined the specific conditions under which ethical leadership is effective at reducing workplace deviance, and those where it is less so (Babalola et al. 2017; Chuang and Chiu 2017).

In this investigation, we sought to contribute to this discussion by introducing the role of individuals’ moral awareness as an important boundary condition of ethical leadership. Results from two large field studies of working professionals in Turkey (Study 1) and the USA (Study 2), provide robust and consistent support for the view that ethical leadership is most effective in reducing both organization-directed and supervisor-directed deviance, particularly for those employees lacking high levels of moral awareness. This suggests that leaders who attempt to alter employees’ behavior by engaging in ethical leadership practices with all of them, irrespective of their moral characteristics, may be wasting their time by misallocating valuable cognitive, affective and leadership resources. As a result, leaders may need to seek other alternatives or ways to reduce deviant conduct when employees already possess high levels of moral awareness.

Theoretical Contributions

This paper seeks to make several important theoretical contributions to the ethical leadership, moral awareness and employee deviance literature. First, through this investigation we reinforce the power of ethical leaders to shape and positively influence their organizations. Consistent with prior work (Avey et al. 2011; Mayer et al. 2009) and predicted by social learning theory (Bandura 1986), our findings suggest that leaders who engage in ethical leadership behaviors play a critical role in reducing workplace deviance by serving as strong, moral examples for employees to emulate (Chen et al. 2013; Greenbaum et al. 2013; Taylor and Pattie 2014). In this way, our research reinforces the importance of ethical leaders as moral role models who set the tone for organizational expectations and norms around ethical conduct and decision making (Mayer et al. 2009; Neves and Story 2015).

Importantly, our investigation also paints a more nuanced picture of when ethical leadership is most likely to be an effective tool in reducing employees’ deviant behavior. We provide insight into how an important contextual force (i.e., ethical leadership) interacts with a key individual difference (i.e., moral awareness) to yield valued organizational outcomes (i.e., lower organization-directed and supervisor-directed deviance). Although a fair amount of work has already examined how individuals’ personality traits impact their responses to ethical leadership behaviors (Berry et al. 2007; Mayer et al. 2012), research exploring the role of individuals’ moral dispositions on this relationship is still in its infancy. Thus, this paper addresses calls for researchers to simultaneously explore the role of ethical leadership (Brown and Treviño 2006) and ethical predispositions as joint influencers on individuals’ workplace conduct (van Gils et al. 2015). We do so by identifying a new boundary condition—low levels of moral awareness (cf. Arnaud 2010; Kalshoven et al. 2013)—under which ethical leadership exerts a significant influence in reducing employees’ organizational-directed and supervisor-directed deviance. Importantly, we find that this negative relationship between ethical leadership and deviance behavior may be strengthened when employees lack a high level of awareness and understanding around how ethical issues may impact organizational decision making. In situations where employees lack this moral understanding, having a leader who a) communicates an ethics-first message at work, b) helps employees aspire to higher levels of moral achievement and c) consistently acts with integrity in his/her personal and professional life can provide followers with a guiding moral influence they seek to emulate. In this way, ethical leadership is a crucial strategic lever leaders can use to positively influence their less morally aware followers. Through these efforts, leaders not only equip employees to abide by ethical norms of conduct, but also limit the damage done to individual- and organizational reputations that can accrue from employees’ deviant actions (Fehr et al. 2015; Treviño et al. 2000a, b).

This finding, while potentially provocative, is nonetheless consistent with substitutes for leadership theory (Kerr and Jermier 1978). While ethical leadership has been shown as valuable for enhancing organizational functioning and effectiveness (Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009), our findings suggest it is not always critical to ensuring positive ethical outcomes. To the contrary, our research shows that high levels of ethical leadership do little to reduce employees’ deviant actions when they are already predisposed toward understanding issues of moral importance. From a theory-building standpoint, this insight helps to advance the ethical leadership literature by highlighting the construct’s inherent limitations and boundary conditions. By recognizing that individuals have wide and differing perspectives on morality and use different evaluation criteria to assess leader behavior (Giessner and Van Quaquebeke 2010; Henle 2005), we believe researchers can better advance ethical leadership’s conceptual and practical utility by applying it more specifically to certain individuals (e.g., the less morally aware) and/or situations (e.g., where an ethical climate is non-existent) where its influence may be more valuable. In this way, the utility and precision of our leadership theories is enhanced, providing greater value for scholars and practitioners seeking to employ these different leadership behaviors in their work.

Practical Implications

In addition to advancing theory on ethical leadership, moral awareness and deviance, our findings also provide important, practical insights for managers seeking to build more ethical organizations. First, our research indicates that leaders who engage in ethical leadership practices are more likely to see a potential reduction in followers’ deviant conduct, given the strong negative relationship that exists between ethical leadership and employees’ deviance. However, we caution that such an approach is akin to using the proverbial hammer for anything that looks like a nail. As noted above, ethical leadership, despite its numerous purported benefits, is not a “one size fits all” solution to reducing deviant behavior at work. Rather, our findings suggest its influence is conditional, dependent as much on employees’ moral characteristics as it is on leaders’ own behaviors.

We recommend, therefore, that leaders take a more personalized, tailored approach when deciding to whom to exhibit ethical leadership practices. By understanding and being aware that employees’ ethical tendencies, much like their motivations, are unique (van Gils et al. 2015), leaders are better equipped to see a greater return on their investment in ethical leadership practices. Rather than relying upon ethical leadership with all their employees, our findings suggest leaders are better served by being more judicious in how they allocate and expend their leadership resources. Taking the time to understand and appreciate their employees’ personalities, moral dispositions and tendencies can only serve to enhance leaders’ ability to manage them effectively. Whether it be through a battery of personality and behavioral integrity assessments, formal ethics training seminars or other ways of capturing knowledge about their employees’ moral dispositions, leaders would be well served by identifying early on which of their employees would benefit from more intense, focused ethical leadership practices (e.g., continually communicating and reinforcing an ethics-first message) and which of them only need intermittent, infrequent reminders. Doing so can alleviate the burden upon leaders to be all things to all people and free them to be more strategic and targeted in their leadership approach.

A second important practical implication of this work is highlighting the critical role leaders play in selecting and hiring employees who possess the proper levels of moral awareness. Building a culture of ethicality takes time, and hiring the right people who fit the desired culture is one way to minimize acts of workplace deviance (Appelbaum et al. 2005). When leaders begin to include individuals’ moral awareness as a relevant and important selection criterion for employment and/or promotion, this not only increases the likelihood of hiring ethical individuals, thereby lowering deviance in the process, but also communicates and demonstrates to interested observers the organization’s commitment to ethical values. This helps to reinforce and build a healthy ethical climate and culture, while also reducing the “ethical burden” on current and future managers to actively manage ethical missteps.

Yet, if leaders cannot find highly morally aware individuals who also satisfy specific job and/or role requirements, then it becomes incumbent upon leaders to proactively raise their employees’ level of moral awareness, particularly if one of their objectives is to lower the frequency of deviant behavior. Leaders who purposefully seek ways to increase their employees’ understanding of and sensitivity to ethical issues at work can potentially insure themselves against widespread deviant behavior. By helping their employees understand the ways in which ethical dilemmas may present themselves during day-to-day business interactions, leaders can help to foster a more ethical work environment, creating a culture of transparency, honesty and virtue (Arnaud 2010). Thus, looking for creative and engaging ways to raise the collective moral awareness of employees should be a top strategic priority of both senior- and mid-level leaders tasked with setting and executing the organization’s vision.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this investigation makes several important contributions to both theory and practice, like any research endeavor, it is not without limitations, thus reflecting opportunities for future research. While our two studies on two different continents established moral awareness as a significant moderator of the relationship between ethical leadership and employees’ organization-directed and supervisor-directed deviance, our findings are also consistent with prior work which raises the possibility that other specific moral dispositions, such as honesty and humility, may play a role in shaping individuals’ deviant behavior (O’Neill and Hastings 2011). Although ethical leadership exhibited a strong negative impact on deviance for those low in moral awareness across both studies, in Study 1 (Turkish working professionals), we also observed a surprisingly positive trend in deviance among those individuals who rated themselves highly on moral awareness and honesty. Here, we offer three potential explanations for these counterintuitive results and encourage future research to consider their merits.

First, higher levels of honesty may be associated with higher levels of deviance, in part, due to a lack of anticipation or foresight about how their dishonest actions might affect themselves and others. Recent research by Sheldon and Fishbach (2015) and Ariely (2012) suggests that when individuals fail to anticipate temptation or how they might respond to it, even “honest” individuals are highly susceptible to engaging in unethical behavior. Second, individuals who rated themselves highly on honesty and moral awareness may have over reported and/or overestimated their deviant conduct to further magnify their honesty, even if it was about undesirable things, such as workplace deviance. In self-reporting deviant behavior that their less honesty peers may be more inclined to hide or underreport, highly honest individuals may be trying to reinforce their social and moral identities as ethical persons, consistent with established prior research (Aquino et al. 2009). A third potential explanation we offer here is that national culture, organizational culture and/or other unique sample differences may have had an impact, particularly since in the US sample (Study 2), self-reported deviance behaviors were negatively associated with both honesty and moral awareness. Thus, norms of behavior and ethicality may have differed across samples, as could have receptivity to an ethical form of leadership (Eisenbeiß and Brodbeck 2014). We therefore encourage researchers to further explore the antecedents and outcomes of ethical leadership across various national cultures, samples and working environments to better inform our understanding of how ethical leadership operates. Although the current investigation limits our ability to test these various explanations, future research should consider these interesting alternatives.

A second limitation worth noting is the cross-sectional nature of our data. Although the data for these studies admittedly represent employees’ attitudes and behaviors at a moment in time, we attempted to enhance the rigor of our measurement by using established scales and collecting independent and dependent variables at two distinct points in time, thus minimizing the potential for common method variance (CMV) (cf. Podsakoff et al. 2012). Further, the consistent and significant interactions we found across both field samples strongly suggest our findings are not spurious or caused by CMV, consistent with prior research on the nature of interactions (Siemsen et al. 2010). However, we acknowledge the need for more robust approaches to measurement and encourage future research to utilize more longitudinal designs that can help to illuminate how perceptions of ethical leadership develop over time and whether employee deviance occurs in response to a specific triggering event, a compilation of actions or some combination thereof.

While our study identified an important boundary condition of ethical leadership as it relates to supervisor-directed and organization-directed deviance (i.e., moral awareness), we admittedly did not test additional moderators that may also help to strengthen this association, nor did we directly measure the causal mechanism driving individuals to engage in less deviant conduct. Going forward, it will be important for researchers to examine the underlying psychological mechanisms driving individuals to engage in less deviant behavior and how ethical leadership influences these psychological conditions. In addition, we encourage scholars to explore how other newer-genre forms of leadership (e.g., transformational and authentic leadership) (Hannah et al. 2014) may influence other forms of workplace deviance and whether they operate through the same or different causal channels.

A final limitation worth noting is the conceptualization and operationalization of deviance we employed in this research effort. To date, a central effort of the behavioral ethics literature has been to distinguish between unethical behavior and deviant behavior. However, to be able to call a given behavior deviant requires intimate knowledge of individuals’ intentions and motives (Wilks 2011). Whereas unethical behavior is characterized by a breaking of societal rules, deviant behavior focuses on the violation of organizational norms (Spreitzer and Sonenshein 2004). Given this distinction, exploring whether individuals’ level of moral awareness might predict whether they engage in unethical or deviant behaviors would add much needed clarity to the literature. Additionally, future research might also consider investigating the underlying psychological differences between individuals possessing high and low levels of moral awareness. Studies have shown that employees often react to perceived injustices and dissatisfaction (Bennett and Robinson 2000), unfair treatment (El Akremi et al. 2010) or mistreatments (Tepper et al. 2009) quite differently. Understanding the moral and psychological makeup of individuals who respond in these various ways to a lack of ethical leadership would prove valuable.

Conclusion

Ethical leadership is a powerful lever leaders can use to enhance their organizations. Yet, despite the widespread recognition that ethical leaders have the power to influence their organizations in positive and meaningful ways, very little research has been devoted to exploring how certain individual moral factors (e.g., moral awareness) interact with various contextual factors (e.g., ethical leadership) to predict workplace deviance. Our research takes an important step in advancing the literature by focusing on the moderating role of moral awareness as an important boundary condition of ethical leadership. In demonstrating that ethical leadership helps to reduce deviance primarily among those lacking in moral awareness, we contribute to a growing body of work demonstrating that followers’ actions are dependent upon both their moral characteristics (Reynolds 2008; Moore et al. 2012; Chuang and Chiu 2017) and the context under which leadership occurs (Mitchell and Ambrose 2012; Michel et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2015). Looking ahead, it will be important for both scholars and practitioners to recognize that ethical leadership, while beneficial in many ways, is neither a panacea nor a one size fits all solution. Only through its judicious application can organizations reap its many benefits.

Notes

Research suggests there are no significant differences between print and online participant groups on closed surveys, nor differences in participant’s willingness to disclose personally revealing information (Huang 2006; Knapp and Kirk 2003). For example, Hayslett and Wildemuth (2004) examined the relative effectiveness of online vs. paper surveys, paying special attention to response rates, response time/quickness, sampling bias and response differences that could be attributable to the choice of survey medium. Their study detected no sampling bias or differences in content responses. Similarly, Hardré et al. (2012) found no statistically significant differences between paper-based and web-based surveys in terms of overall quality (completeness, coherence, correctness). Finally, in a recent meta-analysis, Dodou and de Winter (2014) compared social desirability scores between paper and computer surveys across 51 studies that included 62 independent samples and 16,700 unique participants. Their findings show that there is no difference in social desirability between paper-and-pencil surveys and computer surveys. Thus, we felt justified in combining participants from both survey method groups.

References

Ahn, J., Lee, S., & Yun, S. (2016). Leaders’ core self-evaluation, ethical leadership, and employees’ job performance: The moderating role of employees’ exchange ideology. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3030-0.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions Sage. CA: Newbury Park.

Appelbaum, S.H., Deguire, K.J., & Lay, M. (2005). The relationship of ethical climate to deviant workplace behavior. Corporate Governance, 5(4), 43–56.

Aquino, K., Freeman, D., Reed, A., II, Lim, V. K., & Felps, W. (2009). Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: the interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 123–141.

Ariely, D. (2012). The (honest) truth about dishonesty. New York: Harper Audio.

Arnaud, A. (2010). Conceptualizing and measuring ethical work climate development and validation of the ethical climate index. Business and Society, 49(2), 345–358.

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., & de Vries, R. E. (2014). The HEXACO Honesty-humility, agreeableness, and emotionality factors: A review of research and theory. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(2), 139–152.

Avey, J. B., Palanski, M. E., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2011). When leadership goes unnoticed: The moderating role of follower self-esteem on the relationship between ethical leadership and follower behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(4), 573–582.

Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., & May, D. R. (2004). Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), 801–823.

Babalola, M. T., Stouten, J., Camps, J., & Euwema, M. (2017). When do ethical leaders become less effective? The moderating role of perceived leader ethical conviction on employee discretionary reactions to ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3472-z.

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 421–458.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social-cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Baron, R. A., & Neuman, J. H. (1998). Workplace aggression—The iceberg beneath the tip of workplace violence: Evidence on its forms, frequency, and targets. Public Administration Quarterly, 21, 446–464.

Bedi, A., Alpaslan, C. M., & Green, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(3), 517–536.

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–363.

Berry, C. M., Ones, D. S., & Sackett, P. R. (2007). Interpersonal deviance, organizational deviance, and their common correlates: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 410–424.

Bies, R. J., & Tripp, T. M. (1998). Revenge in organizations: The good, the bad, and the ugly. In R. W. Griffin, A. O’Leary-Kelly, & J. M. Collins (Eds.), Dysfunctional behavior in organizations: Non-violent dysfunctional behavior (pp. 49–67). Stamford, CT: JAI Press.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Bordia, P., Restubog, S. L., & Tang, R. L. (2008). When employees strike back: Investigating mediating mechanisms between psychological contract breach and workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 1104–1117.

Brown, M. E., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Ethical and unethical leadership. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(4), 583–616.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134.