Abstract

The study examines the research methodology of more than 200 empirical investigations of ethics in personal selling and sales management between 1980 and 2010. The review discusses the sources and authorship of the sales ethics research. To better understand the drivers of empirical sales ethics research, the foundations used in business, marketing, and sales ethics are compared. The use of hypotheses, operationalization, measurement, population and sampling decisions, research design, and statistical analysis techniques were examined as part of theory development and testing. The review establishes a benchmark, assesses the status and direction of the sales ethics research methodology, and helps inform researchers who need to deal with increasing amounts of empirical research. The investigation identified changing sources of publication with the Journal of Business Ethics and the Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management maintaining their position as the main conduit of high quality empirical sales ethics research. The results suggest that despite the use of theoretical models for empirical testing, a greater variety of moral frameworks and wider use of marketing exchange theory is needed. The review highlights many sound aspects about the empirical sales ethics research statistical methodology but also raises concerns about several areas. Ways in which these concerns might be addressed and recommendations for researchers are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interest in marketing ethics has increased dramatically over the preceding 50 years with a tenfold increase in the number of marketing ethics publications (Schlegelmilch and Öberseder 2010). This increased interest has featured a deepening of the debate in sub-disciplines and the introduction of new topics. In the 1980s, sales-related themes were the most important aspect of this interest, as measured by the number of publications and citations (Schlegelmilch and Öberseder 2010), and ranked equal third in terms of the number of marketing ethics publications between 1981 and 2005 (Nill and Schibrowsky 2007).

There have been more than 20 assessments of the business, marketing, and sales ethics research over the past 30 years. The focus of these assessments has included the discipline’s conceptual foundations, empirical findings, research direction, research methodology, contribution and utilization of knowledge, and methods of measurement. Of special note is the continuing discussion of theoretical foundations and research methodology in several of the reviews. The assessments, summarized in Table 1, have assisted in the critical analysis, the development of research agendas, and the conceptual and empirical direction necessary to accommodate practitioner and academic interest in the field.

Compared to the business and marketing ethics disciplines, there are fewer assessments of the research in personal selling and sales management ethics, despite being a very important part of business ethics in terms of general interest and publications. Swan et al. (1991) analyzed the contribution to and utilization of sales management knowledge but did not focus specifically on ethics research. Bush and Grant (1991, 1994) continued the work of Swan et al. (1991) also including theoretical foundations. Bush and Grant (1994) examined the content of 358 articles in sales force research from four marketing journals between 1980 and 1992 identifying that the research was becoming more rigorous. Part of their investigation determined the extent to which sales force research had been theoretically grounded and identified the disciplines that were most influential in guiding this research. A comprehensive review of the business marketing research published in the Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management by Reid and Plank (2000) identified a small number of ethics articles. The only reviews dealing directly with the personal selling and sales management ethics research are those by McClaren (2000, 2013) focusing on empirical findings, conceptual foundations, and managerial implications. Previous reviews of sales ethics literature have not focused on research methodology despite researchers now needing to deal with large amounts of empirical research.

Without periodic evaluation, sales ethics researchers risk losing the direction and impetus that keeps their research at the forefront of the business ethics discipline. Particularly, there is an absence of reviews and critical evaluations of the methods used in the personal selling and sales management research (McClaren 2013). The objective of the present study is to fill this gap by assessing the empirical research methodology used in sales ethics research. To inform sales ethics researchers, the first part of the present review begins by identifying the theoretical ethical foundations of the business and marketing ethics research to enable a comparison with the sales ethics research. These sections include identifying the research to be incorporated in the review and categorizing the theoretical frameworks identified in the search of the literature in terms of publication outlets, level of theoretical development, and authorship.

Randall and Gibson (1990) highlighted the importance of theoretical foundations as the driver of quality empirical research, and the structure of their review was adopted as an organizing template for the present study. The present review continues by synthesizing previous assessments of theory development and empirical research methodology in the business and marketing literature to enable a comparison between this research and the theoretical foundations in sales ethics research. The second main part of the review examines the use of hypothesis testing, operationalization and the source of instruments, and the reliability and validity of measures. The review continues by assessing study populations, sampling decisions, research designs, response rates, and statistical analysis techniques. Theoretical and empirical conclusions for sales ethics researchers are provided in the final section.

Selection of the Sales Ethics Studies

The personal selling and sales management ethics literature was searched for empirical and conceptual articles. First, all articles included in preceding reviews of the sales ethics literature by McClaren (2000, 2013) were included. Second, data bases were searched using EBSCOhost with Business Source Complete and Academic Source Premier for peer-reviewed journal articles from 1980 and including 2010 publication dates. Business Source Complete contains approximately 1,300 journals and Academic Search Complete includes more than 7,800 peer-reviewed journals. These searches used combinations of “ethic*”, “sales”, “selling”, and “sales management” in the title field. Duplicates, publications identified previously, book reviews, and articles unrelated to ethics in personal selling and sales management, such as those about selling financial securities and work ethic, were not included in the final list. Errata and articles in languages other than English were also excluded. The result comprised 222 normative and empirical articles. Of these 222 articles, nine were reviews of the literature, 19 were unrelated to the present review, 37 were normative, and the remaining 157 were empirical investigations of personal selling and sales management. Each article was then examined for its relevance to ethics research in personal selling and sales management. Forty-four articles were removed from further consideration because they covered areas other than ethics, or because they dealt with subjects other than sales (e.g., students, customers, or primarily marketers), leaving 113 empirical ethics articles. These remaining articles included only investigations of sales and marketing practitioners, sales organizations, and sales students.

Not including reviews of the literature and articles unrelated to this review, 37 of 150 sales ethics articles were normative (25 %) and 113 positive (75 %). This compares to Nill and Schibrowsky (2007) who found that 37 % of marketing ethics articles were normative and 63 % positive, and who noted that since 1985 the ratio of positive versus normative marketing ethics publications has been increasing. It appears that the lack of normative marketing ethics research noted by Schlegelmilch and Öberseder (2010) is more pronounced in the sales ethics area. Randall and Gibson (1990) included 94 empirical business articles from 31 journals over the 15-year period 1974–1989, citing four empirical sales ethics articles from four journals. The present review identified 113 empirical sales ethics articles from 28 journals suggesting an increasing and widespread interest in the area, as shown in Table 2. The number of articles increased from 12 between 1980 and 1990 to 40 between 1991 and 2000, and then to 61 between 2001 and 2010. Although the number of years covered in the present study is twice as many as in Randall and Gibson’s (1990) study, the number of empirical sales articles represents a dramatic increase in interest. Table 2 shows that the Journal of Business Ethics and the Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management had an approximately equal number of articles published and accounted for nearly 60 % of the total number of articles. These two journals maintained similar shares of the number of articles published across the three review periods. This compares to Nill and Schibrowsky’s (2007) finding that the Journal of Business Ethics and the European Journal of Marketing accounted for approximately 44 % of all marketing ethics articles, and that the European Journal of Marketing had a comparatively higher number of normative contributions.

Significant Theories Models and Frameworks

Randall and Gibson (1990) assessed the studies according to whether theory development was not present, unclear, weak, or strong. They did not, however, provide the criteria for their assessment. The present review categorized the theoretical development of the 113 articles, shown previously in Table 2, in a similar manner using the following criteria. The first category, labelled “Theoretical”, contained studies that included clear statements of the theoretical foundations being utilized. These studies were characterized with clear definitions of the constructs and conceptual components under investigation and espousing a clear theoretical relationship or sets of relationships based on preceding models, theories, frameworks, and conceptual or empirical research. Such studies were also typified by the inclusion of frameworks allowing for the classification of information, stated causal-type relationships, and were likely to include specific sections clearly addressing theory. They frequently provided models diagrammatically representing conceptual, theoretical, and empirical relationships.

The second category, labelled “Weak”, contained studies that provided some theoretical foundations, but were typified by general statements or reviews of the literature describing relationships arising from other research. Such research cited lists of studies relevant to the area being investigated, but the nexus between previous research and the current study was not espoused in detail. Some of these studies provided hypotheses and stated generically that they were based on a review of the literature. Overall, these studies did not move beyond stating that a certain theory somehow explained or was related to the topic being investigated. The third category, labelled “Descriptive”, included studies lacking theoretical foundations or in which it was unclear whether theoretical development was present.

A group labelled “Classification” was added to Randall and Gibson’s (1990) original categorization. This included 11 studies where the main focus of the research was to empirically categorize, group, and describe phenomena based on the application of a framework or to develop research instruments or scales. It is important to distinguish between this and other research because typologies are a bridge between theory and empirical research, guiding conceptualization, instrument development, and data collection and interpretation (Brinkmann 2002). Examples of studies in this group are Ross and Robertson’s (2003) development of a typology of situational factors and scale development studies (Amyx et al. 2008; Dabholkar and Kellaris 1992; Lavorata 2007).

During 1980–2010, and not including the 11 classification articles, 32 (31 %) of 102 articles were categorized as descriptive, with 18, 8, and 14 articles published in the early, middle, and recent periods. A total of 8 articles (8 %) were weak in theory development during 1980–2010, with 1, 3, and 4 articles published in the respective periods. Twenty-seven theoretically strong articles were published in 1991–2000 and 35 during 2001–2010, totally 62 articles (61 %). Of particular interest is the changing level of theoretical development in articles. Articles strong in theoretical development were not present in the period 1980–1990 but accounted for 62 % of the articles published in the period 2001–2010. The Journal of Business Ethics (JBE) and the Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management (JPSSM) accounted for 43 of the 63 theoretically strong articles published between 1980 and 2010.

For the following analysis the articles were grouped only as “Descriptive” or “Theoretical”. Again, not including articles grouped as classifications, the number of descriptive articles remained fairly constant as a percentage of the total number of all articles published in the middle and recent periods, comprising 29 % of 38 articles in 1991–2000 and 33 % of 54 articles in 2001–2010. Table 2 shows that theoretical articles remained fairly constant as a proportion of the total publications for these two periods, comprising 71 and 66 %, respectively.

When the articles are examined by journal outlet, the findings show that 113 articles were published in 28 different journals, shown previously in Table 2. Nine different journals published articles in 1980–1990, ten different journals in 1991–2000, and 13 in 2001–2010. A point of interest is the increase in and changing sources of publication. Although the total number of publications increased by approximately 50 % from the middle to recent periods, the number of journals in which these articles were published increased from 10 to 13, suggesting an increasing concentration of publications in certain journals. A feature of the publication outlets is that, not including the JBE and the JPSSM, four journals published articles in more than one of the three periods. Combined, the JBE and JPSSM accounted for 58 % of 113 articles published between 1980 and 2010 and 68 % of the 63 theoretically driven articles published in the same period. This suggests that although the number and diversity of outlets have increased, the JBE and JPSSM are the main vehicles for sequential, systematic publication of theoretically driven empirical sales ethics research.

Another interesting feature of the theoretical articles and their publication outlets is that they were published in eight different journals in 1991–2000 and nine different journals in 2001–2010. However, not including the JBE and JPSSM, the publication outlets that published strong theoretical articles in 1991–2000 were not the same journals that published strong theoretical articles in 2001–2000. For example, the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science published two theoretical articles in 1991–2000 but none between 2001 and 2010, and the Journal of Business Research published four theoretical articles between 2001 and 2010 but none preceding this period.

When the JBE and JPSSM are compared, the results show they held approximately equal shares of the total number of descriptive articles published in the periods 1980–1990 and 1991–2000. However, as shown previously in Table 2, the share of descriptive articles published in the JBE increased to seven articles or 39 % of the 18 descriptive articles published in 2001–2010, while the percentage of descriptive articles published in the JPSSM decreased to one article (6 %). The preceding findings suggest that although there are large and increasing numbers of outlets for descriptive and theory-driven sales ethics studies, a much smaller number of journals are the main conduits for dissemination of this research. The findings also suggest that although the overall proportion of descriptive and theoretical articles has remained similar, researchers and practitioners should look to certain journals for the consistent publication of strong theoretically based articles.

Although Randall and Gibson (1990) did not include analysis of authorship in their review, it can inform researchers about theoretical research development. One-hundred and forty-one different researchers were identified in the period 1980–2010 from 116 different articles. The results show that the total number of different authors increased across each of the three periods from 15 to 85 authors, totalling 141 authors over the review period. The citation average has fluctuated slightly at 1.73, 1.52, and 1.71 citations per author over the respective review periods, averaging 1.86 citations per author between 1980 and 2010. An increasing number of authors combined with a fairly stable citation rate suggest there is a core of relatively more prolific authors.

The analysis also identified the most prolific authors of theoretical research and other relevant patterns in the research output. The data were examined for information about the number and frequency of theoretical research publications, the authorship of this research, and the continuity of research output by author. Authors with fewer than three articles and authors with no theoretical articles were deleted from the analysis. Table 3 ranks the remaining 21 authors by the total number of theoretical publications over the period. Five of the top ten ranking authors of theoretical papers were published in two or more of the periods. It is important to bear in mind that studies are published on their merit rather than for the use or otherwise of theoretical foundations, and that the provision of theoretical foundations is also related to the period in which articles were published. Authors with longer publishing histories are more likely to be included in both categories.

Empirical Contributions to Theory

It is useful to review the nature and application of theoretical foundations and empiricism in business and marketing ethics to shed light on the drivers of sales ethics research. Twenty-six percent of business ethics studies between 1972 and 1990 were strong in theory development, the balance presenting no theoretical foundation (Randall and Gibson 1990). Twelve of 26 scenario-based studies published between 1961 and 1990 indicated a theoretical foundation for the empirical assessment (Weber 1992). Ford and Richardson (1994) found that the lack of effort, especially empirical effort, directed toward theory testing had led to a paucity of empirical research grounded in theory and had substantially impeded the development of the field. Business ethics research prior to 1993, was characterized as being strong in the application of empirical research to managerial practice rather than to the generation of theory, having few researchers engaged in the generation of comprehensive models of ethical behavior, and where the deficit in empiricism was its contribution to theory (Robertson 1993). Broader models of ethical behavior, specifying individual and organizational variables, and taking contextual factors into account were needed (Robertson 1993). The empirical ethical decision-making literature featured a continuing lack of studies with strong theoretical grounding, a lack of formal hypotheses, and an increasing discussion of construct development rather than theory (O’Fallon and Butterfield 2005).

Although approximately 70 % of sales force studies used at least one theoretical foundation (Bush and Grant 1994), one of the barriers to overcoming the problems in building sales ethics theory had been the scarcity of empirical sales research (McClaren 2000). The few models proposed for the sales component of organizations had generally not provided the same impetus as those in marketing (McClaren 2000). More work is needed in developing the conceptual understanding of sales ethics, in the theoretical grounding of research, in developing theory, particularly predictive theory, grounded in ethical decision-making models, and in the operationalization and measurement of (un)ethical behavior (McClaren 2013).

A continuing concern of reviewers of the business and marketing research has been about the source and development of its conceptual foundations. Early reviewers’ assessments of the ethical foundations in business ethics concluded that competing strains of moral philosophy had been largely ignored, that it included the measurement of moral development, that it included normative models of decision-making, and incorporated theoretical foundations from outside moral philosophy, as summarized in Table 4. More recently, reviewers have noted studies grounded in theory also frequently drew from social psychology.

Theoretical Foundations in Sales Ethics Research

In the light of the preceding discussion, the empirical sales ethics articles were examined for theoretical and conceptual frameworks. The introduction of theoretical models for empirical testing occurred mainly during 1991–2000 and became much more prominent in certain areas during 2000–2010. Including and extending theoretical foundations as a part of research has become a feature of positive sales research, possibly in response to calls for stronger theoretical foundations by Randall and Gibson (1990), McClaren (2000), and others. The research was grouped into six main areas to clarify the development of theoretical foundations. These groupings are arbitrary and this categorization is done only to facilitate a comparison of the foundations between the two recent research periods.

The moral frameworks adopted in 1991–2000 included theoretical underpinnings particularly from utility theory (Etzioni 1988), moral reasoning (Kohlberg 1969, 1981; Kohlberg and Candee 1984; Rest 1986a), moral relativism (Reidenbach et al. 1991), and ethical theory (Frankena 1973). Syntheses of applied ethics were extended minimally during 2000–2010, for example, with Beauchamp and Bowie’s (1979) ethical theory. Sales ethics research might benefit from broadening the foundations of its moral frameworks. Although virtue ethics, Kantianism, and utilitarianism are the most prevalent ethical theories in the business ethics literature (Arnold et al. 2010), sales ethics researchers might consider ethical intuitionism. Application of theories of ethical intuitionism might clarify if a sales practitioner’s unconscious principles or immediate, emotional reactions influence moral commitment. Sales ethics researchers might also consider their understanding of consequentialism. Although most mainstream ethical approaches incorporate a relationship between moral commitment and moral judgments, Lombrozo (2009) challenges that moral commitments are explicitly applied as a basis for moral judgment, that the relationship between moral commitment and moral judgment is imperfect, and that improvement in the measurement of consequentialist commitment is required.

Empirical sales ethics researchers have made substantial progress during 1991–2000 in the application of existing theory to decision-making in the sales area. This research can be characterized as being based conceptually on contingency theory (Ferrell and Gresham 1985; Ferrell et al. 1989), deontological and teleological theories of moral philosophy (Hunt and Vitell 1986, 1992; Jones 1991; Sutherland and Cressy 1970; Trevino 1986), and attitude and behavior (Bommer et al. 1987; Dubinsky and Loken 1989). Of note during this period was the introduction of the first sales ethics decision-making model (Wotruba 1990). Noticeably, several models have been refined and expanded to provide more comprehensive explanations of decision-making. More recently, Laczniak (1983, 1993) received attention and Laczniak and Murphy (2006) outline many of the normative theoretical foundations that may be beneficial for further empirical sales ethics research. Investigations into the social contract between sales practitioners and customers as means, rather than ends to a profit, may prove worthwhile. The same model might be used to investigate the fit between the moral and professional responsibility of sales managers and societal expectations. Noticeably, Ferrell et al. (2007) provide an ethical decision-making framework and empirical research agenda specifically for selling and sales management contexts. Researchers might explicate this framework to become an even more detailed theoretical structure for sales research. Cohen and Reed’s (2006) attitude formation, retrieval, and reliance model integrates attitude formation and change theory, such as that by Ajzen (1991), with those focusing on the impact of attitudes on behavior (Petty et al. 1995). This model could provide theoretical foundations for sales ethics researchers to extend previous studies based on the theory of planned behavior.

Management models during 1991–2000 included research based on theories of climate and organizational environment (Victor and Cullen 1987, 1988), social learning (Bandura 1977; Guzzo and Gannett 1988), career stage (Cron and Slocum 1986), prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky 1979), and leadership theory (Ramsey 1998; Burns 1978). During the period 2001–2010 the increased use of frameworks became more prominent in the areas of role theory (Aldrich and Herker 1977; Kahn et al. 1964; Merton 1957; Michaels et al. 1987; Rizzo et al. 1970), socialization (Feldman 1976, 1981; Fisher 1986; Schein 1965, 1968; Van Maanen 1976; Van Maanen and Schein 1979), social exchange (Aryee et al. 2002; Blau 1964; Lewicki and Bunker 1995; Mayer et al. 1995), and climate theory (Carroll 1979; Deal and Kennedy 1982; Mowday et al. 1979). Sales ethics researchers may find it worthwhile to incorporate management theory from other areas. The integrative model of organizational trust (Mayer et al. 1995) may provide a useful theoretical foundation for sales ethic research by explicitly encompassing relationship-specific boundary condition and the factors involving trust between two parties. The theoretical underpinnings of the model could be extended to include relationships between trust and ethical decision-making. Social exchange theory might be used as a theoretical foundation to explore the influence of ethics on the relationships between social justice, trust, and sales practitioner job outcomes, similar to research by Aryee et al. (2002).

Empirical research about individual characteristics in the period 1991–2000 incorporated theoretical foundations particularly from attitude change (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980; Fishbein and Ajzen 1975, 1979), attribution and expectancy theory (Jones and Davis 1965; Kelley 1967; Mitchell et al. 1981; Rosen and Jerdee 1974; Shaver 1975; Vroom 1964), and goal theory (Locke 1968; Locke and Latham 1990). Other theories incorporated during this period included gender theory (Gilligan 1982, 1987), values (Liedtka 1989), and script theory (Schank and Abelson 1977). The use of theoretical foundations increased between 2000 and 2010 to extend attitude change theory (Ajzen 1991, 2001) and goal theory (Greene 1979; House 1971, 1996; House and Dressler 1974). Theory introduced in this period included person–organization fit (Chatman 1989; Netemeyer et al. 1997; O’Reilly et al. 1991), leadership theory (House and Dressler 1974; Sosik and Godshalk 2000), social identity and identification (Kelman 1958; Tajfel and Turner 1979), and dissonance theory (Viswesvaran et al. 1998).

Sales ethics researchers may also benefit from extending social identity theory (Kelman 1958; Tajfel and Turner 1979) to include foundations from Ashforth and Mael’s (1989) earlier conceptualizations and more recent work incorporating relational identity (Sluss and Ashforth, 2007, 2008; Ashforth et al. 2007, 2008). This research provides theoretical foundations underpinning how role- and person-based identities create relational (i.e., supervisor–subordinate) identities. Application of this model may extend current knowledge about how supervision influences salespeople’s role conflict and ambiguity, ethical decisions, and performance. Sales ethics research might also examine if relational identification develops in salesperson–customer dyads and the effect this may have on ethics in the selling relationship. Such investigations would not only identify the managerial and selling tasks and individual characteristics that contribute to role and person identity but enhance our understanding of the influence of selling contexts and ethical decision-making.

Taxonomies were grouped as part of “Classifications” to clarify the application of conceptual foundations and for the reasons mentioned previously. Taxonomies applied in 1991–2000 included categorizing ethical position (Forsyth 1980, 1992), cultural values (Hofstede 1983, 1991; Hofstede and Bond 1984; Hosmer 1985; Rokeach 1968), and facilitators (Katz and Kahn 1978). The taxonomies introduced during 2001–2010 were new to the area and included supervisor orientation (Kohli et al. 1998), selling-customer orientation (Saxe and Weitz 1982), training needs (Steel and Ovalle 1984), and situational factors (Ross and Robertson 2003). Ross and Robertson’s (2003) findings suggest that their situational taxonomy should be applied in sales ethics studies to more clearly identify differences in the effect that universal, particular, direct, and indirect factors have on decision-making. Darmon’s (1998) classification of selling positions by information load, complexity of information processing, and the relative importance of time and relationship management would also contribute to sales research by identifying differences in salesperson–customer dyads and ethical decision-making.

Marketing exchange theory used in 1991–2000 included relationship marketing frameworks by Crosby et al. (1990) and Dwyer et al. (1987). These were extended during 2000–2010 with Jaworski’s (1988) theory of marketing control. This area is perhaps where sales ethics researchers most need to integrate new theory. As an instance, the theoretical understanding of relationship marketing has been extended recently by Palmatier et al. (2013) who included “relationship velocity” to describe the rate and direction of changes of trust, commitment, and norms in relationships. Sales ethics researchers might extend the present understanding of ethical salesperson–customer relationships by integrating this theoretical development in their research. In a similar manner as Palmatier et al. (2013) view relationship velocity as comprising rate and direction, sales ethics researchers might better understand how and why ethical salesperson–customer relationships change over time. Although controversial, theoretical foundations from game theory (Von Neumann and Morgenstern 1944) could provide a useful understanding of selling relationships, particularly those characterized by different levels of information, various amount of negotiation, the number of participants, and the duration of the relationship.

To summarize, the present review found that about 70 % of sales ethics studies provided theoretical foundations and about 60 % were “strong” in the use of theory. The inclusion of theoretical frameworks as part of sales ethics research appears to have increased during the review period and this issue is not as great a concern as in the past. Between 2001 and 2010 management models and individual characteristics were the most prevalent theoretical foundations introduced to the sales area. In comparison, the introduction of decision-making models, taxonomic and moral frameworks, and exchange theory were less prevalent as research foundations. The sales ethics research still needs greater variety in the introduction of moral frameworks and marketing exchange theory. The present review confirms Bush and Grant’s (1994) finding that although sales force research has been grounded in solid conceptual foundations, the majority of these foundations are derived from organizational psychology. Theoretical perspectives from other areas of psychology and from other disciplines are still needed to inject new ideas and frameworks into sales ethics research. These areas might include social and cognitive psychology, sociology, anthropology, learning theory, and finance. Although Bush and Grant’s (1994) recommendation to shift from survey-driven research to testing theory has been widely adopted, sales ethics researchers appear to have ignored the emerging attention to relationship marketing identified by Bush and Grant as early as 1994.

Particularly, the present review identified the lack of application of marketing exchange theory and, more recently, the introduction of few moral frameworks in sales ethics research. Investigators need to generate new theory or extend existing marketing exchange theory specifically for sales contexts. Bush and Grant (1994) also considered that failing to include consumers and buyers was to neglect half the relationship. Although the criteria for including articles in the present review excluded studies solely of customers, research founded on exchange theory would necessitate examination of sales and customer aspects of the dyad. The present review found that less than 2 % of studies included customers in their samples, as discussed in following sections, and reinforces the continuing need to include combined samples of customers and sales practitioners in sales ethics research.

The present review also identified that the introduction of further moral frameworks is warranted. Reviewers consistently note the development of models attempting to explain and predict managerial decision-making (Ford and Richardson 1994). Nill and Schibrowsky (2007) found that research into how marketers arrive at ethically relevant decisions commenced in the 1980s under the influence of positive decision-making models, such as the Theory of Marketing Ethics (Hunt and Vitell 1986) and that much of the subsequent research was positive research about normative issues based on this model. Reviewers have also consistently noted the use of and the need to move beyond ethical prescriptions in marketing ethics based primarily on ethical theories of teleology and deontology (McClaren 2000, 2013; Murphy and Laczniak 1981; O’Fallon and Butterfield 2005; Tsalikis and Fritzsche 1989).

Methodological Analysis of Sales Ethics Research

The second main part of the article reviews the use of hypotheses and operationalization, reliability, and validity issues. The following sections include analysis of the selection of population, sampling design, sample size and response rate. Research design and statistical technique are assessed in the third main part of the review.

Hypotheses

Randall and Gibson (1990) noted the importance of hypothesis testing for moving beyond exploratory research to testing theory, reporting that only 25 % of studies utilized hypotheses. The present study examined the empirical sales ethics research for formal statements of hypotheses. The following analyses do not include items gathering information about demographic and background variables that are typically gathered as part of the research process and included studies that were previously categorized as classifications. Over the 30-year period, 72 % of the 116 studies used formal hypothesis testing as part of the research method. It is important to note that the use of hypotheses is not the only requirement of theory testing. Hunt and Vasquez-Parraga (1993), as an example, used research questions and an experimental design when testing A General Theory of Marketing Ethics (Hunt and Vitell 1986). The findings, summarized in Table 5, show a dramatic increase in the use of hypotheses from comprising only 20 % of studies during 1980–1990, to constituting 70 % of studies during 1991–2000, with a more moderate increase from 2000 to 2010, during which time they accounted for 81 % of studies.

Other interesting features about the use of hypotheses are evident in the data. First is that the proportion of studies using hypotheses in the present review was similar to that reported by Randall and Gibson during 1981–1990. Second, and considering only the Journal of Business Ethics and the Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, in the period 1991–2000 the number of studies published and the percentages using hypotheses was the same. Eleven of the 15 articles (73 %) published in each journal used hypotheses. In 2001–2010 the number of studies published in the Journal of Business Ethics increased by a third from the preceding period and the proportion of studies using hypotheses increased slightly to 75 %. During the same time, the number of studies published in the Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management increased by 13 % from the preceding period and the proportion of studies using hypotheses increased to 88 %. While the total number of publications by these two journals has remained fairly similar over the three periods, most recently the JPSSM has favoured studies using hypothesis testing as part of the research method over studies without this aspect in their design.

The third finding of importance in theory development is reflected by 55 of the 60 studies (92 %) categorized as “strong” in theoretical development also using hypothesis testing. Noting that two further studies were partial tests of A General Theory of Marketing Ethics using research questions and experimental designs (Hunt and Vasquez-Parraga 1993; Menguc 1998), and therefore not categorized strictly speaking as including formal hypotheses, this proportion is increased further. Clearly, hypothesis testing is central to sound theory development. It is important to note here that the review process first categorized the studies as descriptive or theory development by an examination of the conceptual foundations underpinning the research, not on the use of hypotheses. The presence of hypotheses as part of the “strong” research design helps confirm the prior categorization of the research.

The fourth facet of relevance to theory development is that the proportion of strong theoretical articles using hypotheses tests has increased over the preceding two review periods. Between 1991–2000 and 2001–2010 the number of theoretically strong studies increased from 21 to 33, or in percentages, from being 38 % of studies in 1991–2000 to constituting 62 % of publications during 2001–2010. It is illuminating that publication outlet and the use of hypotheses is associated with the level of theoretical development in studies. Collectively, 68 studies were published in the top six journals ranked in terms of using hypothesis testing (i.e., in JBE, JPSSM, MMJ, JBR, JAMS, and EJM). This was approximately 82 % of the 83 studies published in 1980–2010 using hypothesis testing. In the two most recent periods these top six journals published 92 % of the theoretically strong studies and 57 % of those categorized as theoretically weak.

Operationalization, Reliability, and Validity Issues

Randall and Gibson (1990) recommended building a cumulative database of business ethics where researchers will clearly define key constructs, provide a shared understanding of what is meant by ethical beliefs and conduct, provide reliable and valid measures for theoretical constructs, and establish face validity so multidimensional constructs tap all dimensions. Randall and Gibson (1990) suggested that researchers needed to have greater concern when operationalizing theoretical constructs and that more attention to the reliability and validity of instruments was required. Bush and Grant (1994) found an abundance of survey-driven research and recommended that research needed to begin theory testing, focusing on internal validity.

Three hundred and nineteen measures were identified in the sales ethics studies published between 1980 and 2010. A total of 55 measures were excluded from this part of the analysis because reliability assessment using Cronbach’s alpha was inappropriate. Forty-two of these exclusions were because they were single-item measures of the construct or because the research design was such that reliability assessment was not applicable. Seven studies were also excluded because they used the Defining Issue Test where a P-score is reported as a measure of reliability, and six were omitted because they were measures of social desirability. The remaining 264 were examined for evidence of concern for the reliability and validity of the measures.

Overall, the reliability of measures was reported in nearly 80 % of applications. The proportion of studies reporting reliability increased across each of the three periods from 15 % in 1980–1990 to 92 % in 2001–2010. This was done nearly invariably using the alpha coefficient statistic, or Cronbach’s alpha. The exceptions to this were Grisaffe and Jaramillo (2007) who provided a coefficient of reproducibility in their use of secondary data, and Jaramillo and others (Jaramillo et al. 2006, 2009) who used a Guttman-type instrument to measure reliability.

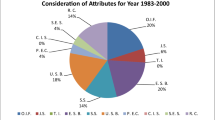

Another demonstration of concern for the reliability and validity of instruments was taken to be examination of the structure of the data, particularly through the use of factor analysis. Slightly more than half of the 264 measures used from 1980 to 2010 were examined using various types of factor analysis, described in studies as factor analysis, exploratory factor analysis, and principal components analysis. The proportion of studies employing such techniques more than doubled from 32 to 65 % between the second and third review periods. Six of the 319 measures were not included in the following analysis because the information was sourced from secondary data or was collected through interviews. Of the remaining 313 measures, identification of the source was not relevant in a further six instances, the source of the instrument was not stated or was unclear in 13 instances, or were new instruments on 16 occasions. The remaining 278 measures were cited from a previous publication. A comparison across the three periods shows that using instruments from previously published sources occurs approximately 90 % of the time, as shown in Fig. 1.

Several studies developed instruments to identify features of the environment. Examples included the measurement of the ethical perceptions surrounding the use of global positioning systems (Inks and Loe 2005), perceptions of ethical issues in personal selling and advertising (Burnett et al. 2008), and the perceptions of ethical issues in the use of new sales force technologies. Other studies examined the psychometric properties of their new measures in some detail, considering the convergent and discriminant validity of the instrument, their factor structures, the total variance explained by the factors, their reliability, and by providing confirmatory factor analysis of the measures. Most of the new instruments were developed to measure various aspects of the organization rather than the individual. Schwepker and Good (1999) developed a three-item measure of perceived quota difficulty, reporting the factor structure from an exploratory factor analysis, the total variance explained by the factors, the reliability using Cronbach’s (1951) coefficient alpha, the convergent and discriminant validity, and also provided confirmatory factor analysis of the measures. Verbeke et al. (1996) developed measures of various aspects of the organizational control including its control system, its competitiveness, its internal communication, and the organization’s career using the same research methodology. Valentine and Fleischman (2008) developed a new measure of professional ethical standards and corporate social responsibility. A company ethical clarity scale was developed by Ross and Robertson (2003), and Amyx et al. (2008) developed an instrument for measuring the frequency of salespeople’s ethical behavior with customers and their company, and sales peoples’ perceptions of corporate ethical standards and behavior using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Lavorata (2007) tested an ethical climate measurement scale in a French-speaking business-to-business context. Schwepker and Good (2004) developed a measure of sales managers’ ethical attitudes towards company ethics and ethical hiring evaluations using confirmatory factor analysis, and Dubinsky et al. (2004) developed an instrument for measuring retail sales peoples’ perceptions of ethical issues in retailing using exploratory factor analysis.

New instruments for measuring individual characteristics were fewer. Singhapakdi and Vitell (1993) defined professional values as the values that are commonly shared by the members of a profession and operationalized them using the nine items used previously to measure the deontological norms of marketers. Lu et al. (1999) also developed a measure for deontological norms based on the National Association of Health Underwriters, the National Association of Life Underwriters, and the Taipei Life Insurance Association, but appear not to have subjected the measure to factor analysis. Izzo and Vitell (Izzo 2000; Izzo and Vitell 2003) developed an industry-specific instrument for measuring the cognitive development of real estate agents.

Population and Sampling Decisions

An early step in the sampling process is the selection of the sampling method and the source of respondents. One hundred and nine studies were categorized by the research design, population number and characteristics, the sampling frame, and the response rate. Studies that included surveys of more than one population have been identified separately. As an example, Lu et al. (1999) surveyed salesmen in Taiwan and salespeople in the USA. Other examples included surveys of salespeople and sales students. The sample was also identified separately where the same sample was used in more than one article. The list of 122 samples in the following analyses is greater than the list of studies.

Population

The total population from which samples were drawn increased nearly tenfold over the review period. The studies during 1980–1990 were drawn from a population of 2,553 sales practitioners compared to the 21,871 sales practitioners represented in 2001–2010. Although it is not always possible to know the size of the population when using convenience sampling, there are occasions when this number can be reported, such as in the use of student samples. However, 13 studies employed a convenience sampling method with only one study reporting the size of the population from which the sample was drawn.

For the following analysis the studies were categorized into (i) salespeople (non-retail and retail), (ii) sales managers, (iii) sales executives, (iv) students, and (v) combinations of the preceding three categories including customers, other marketers, and marketing managers. Studies by Ferrell et al. (2000), Grisaffe and Jaramillo (2007), Sayre et al. (1991) relied on secondary data. Not surprisingly, approximately 42 % of the 109 studies exclusively surveyed sales people and 22 % surveyed sales managers. Approximately two-thirds of 109 studies exclusively surveyed sales people, sales managers, or sales executives. Turning to combined samples, 25 % of studies surveyed various combinations of sales practitioners, such as (i) sales people and sales managers, (ii) sales managers and marketing managers, and (iii) sales people, sales managers, and sales executives. The proportion of sales practitioners surveyed increases to approximately 91 % when the combined samples are included, as shown in Table 6. This table also shows an increase in the number of studies surveying retail sales people in 2001–2010 from the preceding period, but a decline in the number of retail sales managers being surveyed. The results also found few surveys combining sales practitioners and their customers.

The proportion of sales people populations surveyed using convenience sampling increased from approximately 14 % of studies to 38 % between the two review periods, while the proportion of studies adopting random sampling decreased from 25 to 13 %. A similar increase in the convenience surveying of sales managers is not apparent although a decline of random sampling was evident. Sales managers comprised 27 % of random samples in 1991–2000 but only 15 % during 2001–2010.

Comparisons between the survey populations of sales practitioners in the present study and Randall and Gibson’s (1990) review of the business ethics research should be viewed cautiously. Randall and Gibson (1990) reported that 67 % of studies surveyed practising managers and professionals, with a further 7 % surveying a combination of managers and students, and more than 25 % of studies surveying marketing-related professions. Bush and Grant (1994) found that the majority of sales force studies sampled sales people as the sampling unit, rather than sales managers, and considered that the increasing attention to relationship marketing required researchers to include consumers and buyers. McClaren (2000, 2013) suggested that investigations were needed into the nature of the selling activity, that contentious results among many studies have arisen because job-related responses can vary across settings, that sales ethics research requires greater use of selling taxonomies, and that research is required to establish differences between sales practitioners and other groups, such as marketers.

As mentioned previously, and not surprisingly, the findings indicate sales people and sales managers were the most prevalent population exclusively surveyed, representing 42 and 22 % of 109 studies. Sales people comprised between 37 and 50 % of the studies over the three review periods, averaging about 40 % of studies in the two most recent periods. Surveying sales managers appears to be declining, representing approximately 33 % of studies in the middle period and approximately 16 % in the most recent period. However, as Table 6 showed, these percentages differ when populations of salespeople and sales managers are combined with other practitioners.

The changing composition of populations may be related to the sampling design. Convenience sampling of sales people populations doubled from constituting 37 % of sales people studies during 1991–2000 to comprising 74 % of sales people studies in 2001–2010. The proportion of convenience sampling of sales managers increased less dramatically across the same periods to comprising 10 % of studies. Calls by Bush and Grant (1994) and McClaren (2000) for investigation of sales practitioners and other marketers appear to have gone mostly unheeded, except for those studies combining salespeople and sales managers. The few studies comparing different groups have included salespeople and sales managers (8 %), and salespeople, sales managers, and sales executives (4 %). Calls for the use of selling taxonomies and replication studies have also gone mostly unanswered. Assuming the importance of understanding differences in selling and managerial activities, the lack of comparative studies is an obstacle for sales ethics researchers.

Country of Population

Although Randall and Gibson (1990) did not provide information on the country from which populations were drawn, this information was collected and shown in Table 7. The country was either not stated or was implicitly communicated to be the USA in approximately 39 % of 122 studies. Studies conducted on USA populations comprised 52 or approximately 69 % of the remaining 75 studies. Researchers should clearly state the country of population to avoid ambiguity. Although the studies in Table 7 include single country and cross-culture studies, the findings demonstrate an increasing focus on surveying populations from a greater number of countries, particularly in the most recent review period, and when compared to the two cross-culture studies reported by McClaren (2000).

Sampling Design

The studies were examined for a description of the sampling design, essentially a choice between convenience or random sampling. Overall, 38 % of 109 studies used convenience sampling methods to select potential respondents. A comparison of the research designs used between 1991–2000 and 2001–2010 suggests that while the total number of studies increased by approximately 20 % from 45 to 53 studies, the proportion of studies adopting convenience sampling methods nearly doubled from 12 to 22 studies. Approximately a quarter of studies used a convenience sample design in 1991–2000 but this proportion increased to approximately 42 % in 2001–2010. During the same period, the percentage of studies using random sampling decreased from 67 to 51 %, as shown in Table 8. The number of studies using convenience and random sampling designs are more equal in the most recent review period.

Randall and Gibson (1990) found that business ethics researchers relied primarily on random or convenience sampling to select individuals, reporting that 42 % of studies used convenience sampling and 33 % random sampling techniques. They also noted that random samples have been preferred over convenience samples as they offer the best assurance against sampling bias, because convenience samples offer no assurance of representativeness and do not permit generalization to a larger population, excepting the use of convenience sampling for expert opinion surveys. Randall and Gibson (1990) reported the frequent generalization from convenience samples to larger populations in business ethics research and recommended that researchers should decrease their reliance on convenience samples in favour of random samples. The reliance on convenience sampling is evident in the sales ethics research, at least in the two most recent periods where convenience sampling increased from 27 to 42 % of studies. Although random sampling comprised slightly more than 50 % of studies in the most recent review period, Randall and Gibson’s (1990) call for business ethics researchers to decrease their reliance on convenience samples appears not to have been heeded by sales ethics researchers.

Randall and Gibson (1990) also noted an association between studies of student populations and the use of convenience sampling. Student samples accounted for 26 % of the studies they reviewed, but is less prevalent in the personal selling and sales management ethics research, comprising only 7 % of the 109 studies, shown previously in Table 6. As Randall and Gibson (1990) point out, the use of convenience methods to select samples is not inherently problematic so long as the selection of the sample is appropriate for the purpose of the research. Bush and others (Bush et al. 2007, 2010) adopted a convenience technique to solicit expert opinions about sales force technology. Other instances of appropriate selection of samples include Honeycutt et al. (2004) who investigated sales force training with a judgment sample of Singaporean retail organizations as the unit of analysis. Lee et al. (2009) sourced potential respondents from personal contacts to overcome difficulties of sampling from population lists in China. Sayre et al. (1991) collected secondary data from a census of licensed real estate violation cases. Other studies, such as Verbeke et al. (1996), drew a sample from a journal’s subscription list and requested sales managers distribute questionnaires to salespeople meeting certain criteria. As with Verbeke et al.’s (1996) acknowledgment of the potential bias of managers distributing questionnaires to salespeople who may share their own ethical standpoint, researchers should clearly and fully enunciate the limitations of the sampling method, and provide an evaluation of the extent to which results may or may not be generalized to other populations. Other studies, Chonko and Burnett (1983) as an example, selected one organization as the sample frame, enabling researchers some control over external factors.

The data were also examined for the use of sampling frames. Random samples were drawn from professional associations, commercial list providers, and occupational registration lists. Although the early period is characterized by the use of professional associations as sampling frames for both convenience and randomly drawn samples, their use declined from 54 % of studies during 1980–1990 to 16 % of studies from 2001 to 2010, as shown in Table 9. The proportion of studies using commercial lists remained comparatively stable at around 31 % of studies during the middle and most recent review periods. It is surprising that the use of registration lists, which might provide a census of practitioner groups such as real estate agents or financial service sellers, are used infrequently, constituting about 3 % of studies.

Convenience samples accounted for 35 % and random sampling the remaining 65 % of the studies during 1991–2000. This period was notable for the introduction of commercial list providers, which accounted for approximately a third of the studies. Other sampling frames used in the periods were registration lists, for example, of insurance sales agents registered with government agencies. Compared to the preceding period, the use of convenience samples increased during 2001–2010 to account for 57 % of the 60 studies, and the use of random sampling decreased to comprise 43 %.

Sample Size and Response Rate

A large sample size can help minimize sampling error. Using 100 subjects as the minimum sample size, Randall and Gibson (1990) noted that the business ethics research clearly surpasses the minimum, with a mean sample size of 434, a median of 196, and a range from four to 2,856 subjects. Randall and Gibson (1990) highlighted other important aspects about the adequacy of sample size including issues such as how respondents were selected (random or convenience), the distribution of the population parameter (the variable of interest), the purpose of the research project (exploratory or applied), and the intended data analysis procedures (to ensure adequate cell sizes for statistical analysis). Despite the importance of such factors, Randall and Gibson (1990) found the business ethics research infrequently took these factors into consideration when determining sample size, and, as with most social science research, the sample size was fixed by the amount of money available or the sample size used in similar previous research. Randall and Gibson (1990) identified the need for business ethics researchers to consider the issue of sample size more carefully and in light of the purpose of the research, the data analysis techniques, and pre-testing.

The average number of responses in the present review period was 277. Similar to the size of the populations, there was a substantial increase in the overall number of responses included in the period 1991–2000. Although the response rate was not stated in 34 of the 122 studies examined, over the last 20 years there has been a dramatic increase in reporting such that more than 75 % of studies included this statistic. Nevertheless, a concerning aspect was the lack of clarity and the inconsistency in reporting response rates. Although researchers are reporting response rates, they are calculated in a variety of ways. Some studies reported rates as a percentage of the total number of surveys sent, some as a percentage of the number sent adjusted for those not deliverable, and some as the percentage of usable responses. Researchers need to provide clear statements of all the information relevant to the calculation of response rates.

Twenty-four of the remaining 88 studies reported response rates less than 19 %. Approximately 40 % of the studies reported response rates between 10 and 39 %. A decline in response rates is a facet of random sampling about which numerous researchers have commented recently. The data were examined for response rates only in those studies using random sampling for the middle and recent review periods. Between 1991–2000 and 2001–2010 the number of studies adopting random sampling declined by approximately 20 %, from 32 to 26 studies. Overall, random sampling appears to be associated with lower response rates and convenience samples the reverse. A potential cause for the low response rate associated with random sampling is that this method uses physical mail or electronic surveying and consequently the response rates are lower.

A shift in random sampling response rates is most evident in the levels of response rates below 50 %, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The proportion of studies reporting response rates below 50 % accounted for approximately 85 % of the number of random samples in both the 1991–2000 and 2001–2010 review periods. A decline in the proportion of studies achieving “20–29 %” and “30–39 %” levels of response is apparent between the two review periods. These levels accounted for approximately 44 % of studies in 1991–2000 and approximately 12 % in 2001–2010. The higher levels of response (i.e., 20 to 39 %) appear to have been replaced with a “bracket slip” to the lowest two levels of response. The combined response levels of “less than 10 %” and “10–19 %” accounted for approximately 25 % of the studies during 1991–2000 and approximately 58 % of studies during 2001–2010, more than double the preceding review period. The levels of response above 39 % appear not to be as affected by this bracket slip, possibly because of the additional efforts made by researchers to secure responses.

Randall and Gibson (1990) report the mean response rate in business ethics research was 43 %, the median 40, and the range of response rates between 10 and 96 %. Randall and Gibson (1990) found an insignificant relationship between publication date and the response rate, contradicting the contention that response rates are declining in social sciences due to saturation. Randall and Gibson (1990) suggested the cause of low response rates is the sensitive nature of the topic and respondents being unwilling to have their “ethics” measured, and that their unwillingness to divulge incriminating information means that participants may have very different attitudes from non-participants. Given the importance of achieving adequate response rates, Randall and Gibson (1990) made recommendations in three main areas. First, use techniques to encourage higher response rates, such as, targeting and intensively surveying a sub-population, persuading the respondents of the importance of the research topic, and providing incentives. Second, use techniques to determine non-respondent bias. Randall and Gibson (1990) note that, of the business ethics studies reporting a response rate of less than 60 %, only one study compared demographics of respondents and non-respondents to assess response bias. Third, researchers should warn readers not to generalize beyond the sample, although the utility of the study and its contribution to the literature might be questioned if understanding the differences between respondents and non-respondents is an issue.

Although the use of the preceding techniques to ensure responses was evident in much of the sales ethics research, it appeared that higher response rates resulted from putting extra resources into generating responses, usually in requesting participation prior to the survey or from follow-up requests throughout the survey process. Some, but not all, researchers provided comparisons of early and late respondents using t tests and Armstrong and Overton’s (1977) procedure. Most researchers included statements to the effect that their findings could not be generalized beyond the population surveyed.

Research Design

Analysis of the research design utilized in the present review was based on the categories used by Reid and Plank (2000). Surveys or interviews were the most frequently used research design occurring in approximately 83 % of studies, as shown in Table 10. This compares to the 81 % reported by Randall and Gibson (1990) for business ethics research and 80 % reported by Reid and Plank (2000) in the business-to-business research. The use of experiments was fairly constant, fluctuating around 11 % in the present study, higher than both the 6 % reported by Randall and Gibson (1990) and the 4 % reported by Reid and Plank (2000). The frequency of content analysis and multiple designs was similar in the present review compared to the business-to-business research, each at approximately 2 % of research designs. Reid and Plank (2000) found that the business-to-business research included greater use of case study design (9 %) and secondary data (4 %).

Tsalikis and Fritzsche (1989) refer to numerous methods used in ethics research, including laboratory experiments, business game simulations, observational research, and research in which actual ethical decision situations are reconstructed. They noted that the majority of instruments used in collecting ethical data utilize some form of scenarios to which the subjects have to react. Self-report questionnaires, hypothetical ethical dilemmas or vignettes, interview, and records of actual illegal behavior are the four major data-gathering techniques in business ethics research (Robertson 1993). Bush and Grant (1994) noted an abundance of survey-driven research suggesting researchers could adopt experimental research designs, be open to different data analysis methods (as discussed in the following sections), and consider generating alternative perspectives through qualitative research methods. Similarly, Vitell and Ho (1997) note that because of the difficulty of measuring actual ethical behavior, all studies were self-reported measures of ethical behavior rather than actual behavior, and that experimental settings or simulations might overcome the problem of measuring actual behavior. Vitell and Ho (1997) suggested comparisons of the various self-report scales within a single study would improve the overall quality of research. Although experiments and quasi-experiments were a consistent feature of the sales ethics research at around 12 % of studies in each period, their limited use compared to survey research suggests that recommendations by Tsalikis and Fritzsche (1989), Robertson (1993), Bush and Grant (1994), and Vitell and Ho (1997) have largely been ignored.

Randall and Gibson (1990) found the commonly used research designs were survey research (81 %), laboratory experiments and simulations (6 %), in-person interviews (4 %), and a combination of in-person interviews and surveys (3 %). Survey research employed either a direct question format or scenarios. Randall and Gibson (1990) suggested that scenarios and questions were vague and clearly needed to be developed with a greater concern for realism. Randall and Gibson (1990) also viewed the heavy use of close-ended questions as a secondary problem in survey research methodology because problems do not typically present themselves in multiple-choice form. In addition, solutions sometimes need to be invented and close-ended questions are most appropriate when researchers have a well-defined issue and know precisely what dimension of thought they want the respondent to use when providing an answer, and feasible behavioral choices remain loosely defined. Although a free-response format to questions and scenarios may be superior to the close-ended format typically used, Randall and Gibson (1990) found that a free-response format was used in only 5 % of studies. Again, the prevalence of surveys and interviews suggests that, on the whole, researchers in sales ethics research are not addressing the problems of close-ended questions and realism.

Randall and Gibson (1990) found that self-report data, accounting for almost 90 % of the research articles (including research designs involving surveys or interviews) and were almost invariably used as an observation technique as few alternative techniques exist. Because of the problem of the difference between what people say they would do and what they actually do, and the potential social desirability bias in self-reported data, Randall and Gibson (1990) recommend techniques to detect it. The present review revealed few studies utilizing data about actual illegal behavior.

Research designs that were mostly absent in the sales ethics research included replication studies, content analysis, laboratory studies such as those used in neuro-marketing, in-basket exercises, and simulation techniques. Robertson’s (1993) call for meta-analysis has not been met in the sales ethics research although this research design could shed light on specific issues. Loe et al.’s (2000) call for longitudinal studies, specifically into ethical climate and how ethics constructs influence performance over time, has gone unheeded. There were few, if any, longitudinal studies in the sales ethics research. Studies adopting secondary data were also sparse in the literature despite the increased world-wide electronic availability of information.

Statistical Technique

The studies were examined for the main statistical technique used. Randall and Gibson (1990) categorized the studies into those adopting univariate, bivariate, or multivariate techniques. They found that 35 % of studies used only univariate statistics, 46 % used bivariate statistics (mostly t tests), and 19 % used multivariate analysis (analysis of covariance, multiple regression, or log linear logit analysis). The present study found similar use of univariate statistics in the 1980–1990 period, as shown in Table 11. Reid and Plank (2000) found 55 % of studies used descriptive statistics, although the figure includes any use of that technique, rather than sole or primary data analysis as was the criteria in the present review. After descriptive statistics, Reid and Plank (2000) found that correlation, parametric regression, analysis of variance, and exploratory factor analysis ranked as the three most frequently adopted statistical techniques. They also found that structural equation modelling (SEM) was adopted in 8 % of studies, mostly after 1990 and mostly used for confirmatory factor analysis.

The present review confirms Randall and Gibson’s (1990) prediction of an increase in the use of multivariate statistics and, overall, found that the methodology in sales ethics research had undergone substantial improvement, particularly with regard to more comprehensive reporting of the methodologies being adopted. Although the timing is debatable, most reviewers identify a revolution to multivariate techniques occurring between 1986 and 1996 (Randall and Gibson 1990; Ford and Richardson 1994; Loe et al. 2000; McClaren 2000; O’Fallon and Butterfield 2005). O’Fallon and Butterfield (2005) found 24 % of studies used univariate and bivariate statistics and 76 % used multivariate statistics. O’Fallon and Butterfield (2005) also found 36 % used ANOVA, 31 % used regression, and 9 % used path analysis, LISREL or SEM.

Several interesting similarities between the sales ethics research and the business ethics research are apparent. The ranking of the frequency of use of statistical techniques in the present review is similar to the ranking in the business-to-business research. Although the selection of statistical techniques should suit the overall research methodology, with no technique inherently superior to another, there are differences in the frequency of adoption of some techniques. This is probably due to a greater spread of topics and authors in the business-to-business literature and because the number of articles reviewed by Reid and Plank (2000) was more than ten times the number of the present review. Techniques that are more frequently used in the business-to-business ethics research become evident when comparing the sales ethics research between 1991 and 2000 to Reid and Plank’s (2000) findings. A summary of their data is also included in Table 11 for comparison with the 1991–2000 review period. In percentage terms, correlation, regression, structural modelling, exploratory factor analysis, and discriminant analysis techniques were used more frequently, and ANOVA, F and Z tests, and MANOVA less frequently in business-to-business research than in the sales ethics research.

There are at least two aspects to consider in terms of the timing of the adoption of various techniques. Twelve of the 19 techniques that Reid and Plank (2000) reported had also been adopted in the sales ethics research. Perceptual mapping and general non-parametric testing were two techniques not used in sales ethics research between 1991 and 2000 but which were adopted in the most recent review period, albeit in a very low number of instances. Although multidimensional scaling, canonical correlation, conjoint analysis, logistic regression and log linear analysis, and cluster analysis have been used in the business-to-business ethics research, they have not been utilized in the sales ethics research.

The results are not clear on whether or not sales ethics researchers are lagging in the introduction of statistical techniques. The results suggest that ten techniques are the most appropriate statistical tools for a wide variety of business and ethics research. The fact that a similar number of techniques are used infrequently in business ethics research and not used in sales ethics research, tends to suggest that they are specialized techniques not appropriate to the type of survey research that is commonly conducted in sales ethics.

Theoretical and Empirical Conclusions for Sales Ethics Researchers

The present review is limited to the analysis of peer-reviewed journal publications. The search is also limited to articles cited in previous reviews and to those journals accessed through EBSCOhost and, although more than 9,000 journals were included, this may not reflect all studies. The search included only articles published in English. The present review reflects opinions, evaluations, and categorizations made by the author. These may not be the same as those made by other commentators. The review also interprets and draws conclusions from statistical and other information, many of which will naturally be subjective.

Given the proportion of positive compared to normative contributions to the sales ethics literature, researchers should consider the way in which their empirical research contributes to theory development and how normative theory might inform managerial application. Overall, the review highlights that although there has been an increase in the number of sales ethics studies, quality research premised on strong theoretical foundations is found most consistently in a small number of publications and produced by a comparatively small cohort of key authors. This is an advantage and a threat to the sales ethics discipline. On one hand, it is advantageous to have a programmatic stream of high-quality research identifiable in key outlets. On the other hand, there is a risk that with a comparatively smaller number of high caliber researchers, replenishing the pool may prove difficult.

The introduction of theory new to the discipline, the extension of existing theory, and the systematic testing of predictive theory is needed to drive sales ethics research forward. This mostly likely will require the reformulation of some frameworks in a manner more suitable for programmatic research and will be best achieved with the consistent selection of relevant samples, survey methods, and instruments. Particularly, the review highlighted that despite the increasing use of strong theoretical foundations, there is a continuing need to introduce further moral frameworks and foundations from exchange theory. Broadening theoretical moral foundations to include those mentioned previously, and extending management and decision-making models in the way described previously will also advance the sales ethics research.

The review identified a small number of studies classifying and categorizing phenomena. The review distinguished between research classifying our understanding of topics and other types of studies. Although taxonomic underpinnings are required to establish the nature of the selling activity being investigated and the impact situational factors may have on decision-making these are rarely included in studies. Categorizations that reflect current personal selling practices, rather than broad demographic descriptors, are required so that researchers can fully tap the dimensions of ethical conflict. For instance, an exploratory study (McClaren and Tansey 2000) identifying that ethical perspective is associated with some of the dimensions underlying Darmon’s (1998) selling position taxonomy might be expanded.

Clearly, hypothesis testing is now an established aspect of sales ethics research methodology. The two most important journals in the discipline, the Journal of Business Ethics and the Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, publish articles with strong theoretical foundations and hypothesis testing. There may be occasions where greater consideration during the research process can strengthen a study. For example, emerging researchers are advised to consider the target journal early in the formulation of the research design so that the content and the research methodology provide a sound fit with the anticipated outlet. Early career researchers are also advised to consider extending the data analysis method, if possible.

Sales ethics researchers show concern for their instruments with a high proportion of studies using the alpha coefficient and more than half using factor analysis to ascertain some aspects about the reliability and validity of measures. The sales ethics research is now sufficiently abundant to warrant a cumulative database that defines constructs, identifies the measures that have been adopted, and summarizes the reliability and validity of instruments. Such a repository would guide sales ethics research through the plethora of instruments available to them and contribute to the development of programmatic research mentioned previously.