Abstract

We used latent class analysis to identify substance use patterns for 1363 women living with HIV in Canada and assessed associations with socio-economic marginalization, violence, and sub-optimal adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). A six-class model was identified consisting of: abstainers (26.3%), Tobacco Users (8.81%), Alcohol Users (31.9%), ‘Socially Acceptable’ Poly-substance Users (13.9%), Illicit Poly-substance Users (9.81%) and Illicit Poly-substance Users of All Types (9.27%). Multinomial logistic regression showed that women experiencing recent violence had significantly higher odds of membership in all substance use latent classes, relative to Abstainers, while those reporting sub-optimal cART adherence had higher odds of being members of the poly-substance use classes only. Factors significantly associated with Illicit Poly-substance Users of All Types were sexual minority status, lower income, and lower resiliency. Findings underline a need for increased social and structural supports for women who use substances to support them in leading safe and healthy lives with HIV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While much research has examined substance use as a risk factor for sub-optimal HIV treatment outcomes including sub-optimal adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) [1,2,3,4], far less research has investigated poly-substance use patterns, particularly among women and in relation to systems of oppression. Most commonly, previous studies have shown that use of any illicit drug (e.g., heroin, cocaine, amphetamines, opioids) is negatively associated with cART adherence [5, 6]. Other studies looking at different types of illicit drugs have found that stimulant use has the most deleterious impact [7, 8], especially crack cocaine among economically disadvantaged women living with HIV [9]. Regarding alcohol, the most commonly used substance among women in general [10], some studies show any use [5] contributes to sub-optimal adherence while others do not [11] or have implicated frequent use [12,13,14]. Findings on cannabis use are also mixed, with most studies, though not all [15], suggesting no association [3, 6, 16]. Less research has been conducted on tobacco use, however independent associations with sub-optimal cART adherence [4] are reported. How these substances may co-occur among women remains largely unexplored, however, and investigating this in relation to sub-optimal adherence is critical given the attendant consequences to overall health and survival [17,18,19].

Among women with HIV who use substances, growing evidence points to the role of gender-based violence as a contributor to poorer cART adherence. A recent meta-analysis of psychological trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder among women living with HIV in the United States (US) estimated women’s lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence at 55.3% (95% confidence interval (CI) 36.1–73.8%), double the national rate [20]. In terms of recent violence, estimates range from 22% [21] to 50% [22], with higher odds among women who use substances regardless of the type (e.g., problematic drinking, non-intravenous drug use, marijuana, crack) and those reporting other markers of poverty and oppression (e.g., less than a highschool education, housing instability, food insecurity) [21, 23, 24]. The co-occurrence of violence, substance use, and socio-economic disadvantage is particularly common among women with HIV who are involved in street-based sex work [25,26,27] as well as young Canadian Indigenous women healing from historical trauma [28]. Many of these women contend with intersectional stigma associated with HIV, drug use, sex work, race, and low income (among other social categories) [29, 30], which can enhance vulnerabilities to poor health outcomes [31]. Indeed, a large body of evidence shows independent associations between violence and increased risks of both HIV infection [32] and poor outcomes after HIV diagnosis, including reduced engagement in care [33,34,35], lower cART use [33,34,35] and self-reported cART adherence [22], and detectable viral loads [33,34,35].

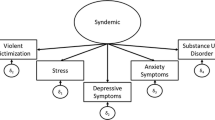

The clustering of substance (ab)use, violence, and HIV/AIDS (SAVA) issues among women at-risk for and women living with HIV has received growing attention in the literature [36, 37]. SAVA has been described as a syndemic [38, 39], or “a set of intertwined and mutually enhancing epidemics involving disease interactions at the biological level that develop and are sustained in a community/population because of harmful social conditions and injurious social connections” [40]. Studies employing SAVA composite variables reveal the synergistic nature of violence, substance use, and other social forces present in women’s lives including poverty, mental illness, and risk of HIV acquisition [41, 42]. The synergistic effects of these epidemics impact treatment outcomes among women living with HIV. For example, a study of 564 women of color found lower odds of viral suppression with higher SAVA scores (odds ratio (OR) 0.81 (95% CI 0.66–0.99), a composite variable combining substance use [dichotomized as ever versus never used illicit drugs (54% of the sample)], binge drinking in the past 30 days (8.5%), lifetime experience of intimate partner violence (27.3%), poor mental health (38%), and sexual risk-taking [37]. These effects may operate through reduced adherence, although this was not measured or controlled for in this study. Importantly, however, recent research suggests that resilience, or the ability to cope positively in the face of adverse circumstances, may be an important buffer against the negative effects of substance use, violence, and other stressors on adherence [43].

While these studies provide insight into the intersecting conditions fuelling HIV-related health inequities, most of these studies dichotomized individuals into substance users or non-users via a single variable asking about illicit drug use, or by asking about specific drug use (e.g., alcohol) rather than measuring multiple forms of substances as well as poly-use. This approach masks important heterogeneity in substance use patterns, since heavy users rarely use a single substance and some drug combinations may be more harmful than others [10]. Further, data are frequently reported for men and women combined with little consideration given to how substance use, cART adherence, or social circumstances differ by gender. To provide a more comprehensive picture, the present study used the SAVA theoretical framework in combination with Latent Class Analysis (LCA) methodology [44] to model multiple types of substance use simultaneously and examine associations with sub-optimal cART adherence, interpersonal violence, and other social determinants of health among a cohort of 1363 women living with HIV in Canada. Analogous to factor analysis for categorical variables, LCA has been used to understand complex substance use patterns and associated factors among binge drinkers [45], people who use injection drugs [46], gay and bisexual men [47, 48], and HIV-negative women [49]. This is the first application of LCA to understand substance use patterns among women living with HIV.

Methods

Study Design

Data for these analyses come from the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS; www.chiwos.ca) [50, 51]. CHIWOS is grounded in community-based research principles [52] and guided by Social Determinants of Women’s Health [53, 54] and Critical Feminist [55] frameworks. Participants were eligible for CHIWOS if they self-identified as a woman (trans-inclusive) living with HIV, were 16 years or older, and resided in British Columbia, Ontario, or Quebec. Between August 27, 2013 and May 1, 2015, we recruited a total of 1424 women with HIV through peers, HIV clinics, AIDS Service Organizations, online networks (i.e., www.facebook.com/CHIWOS; www.twitter.com/CHIWOSresearch), and other methods [56].

Peer Research Associates (PRAs; women living with HIV with research training), administered questionnaires to participants in English or French using FluidSurveys™ software. PRAs received training in community-based research methods (e.g., ethics, confidentiality, good interview practices) and were responsible for recruiting participants, asking the survey questions and entering participants’ responses into the online data collection tool, and engaging in knowledge dissemination (including manuscript co-authorship), among other activities. The baseline visit took place either in-person at clinic or community sites, women’s homes or via phone/Skype, and lasted a median of 120 min (interquartile range (IQR): 90-150).

Wave 2 (18-month) follow-up interviews were completed in February 2017, and wave 3 (36-month) visits are currently in-progress. Ethical approval for all study procedures were provided from Simon Fraser University, University of British Columbia/Providence Health, Women’s College Hospital, and McGill University Health Centre.

Measures

Indicators of Latent Class Membership

Seven substance use indicators for LCA were derived from 18 survey questions on substance use, either in the past year (alcohol and cannabis) or past 3 months (tobacco and illicit drugs). Data reduction was used to reduce LCA model complexity. Each derived variable had three levels, with the frequency of use collapsed into “yes” and “no” responses as well as a third level for “abstainers” who had not used any of the 18 substances measured. Final LCA indicators included: (1) alcohol; (2) tobacco; (3) cannabis; (4) powder cocaine and other party drugs—a composite variable including powder cocaine, ecstasy, MDA, acid (i.e., LCD, PCP), or mushrooms; (5) crack cocaine and other stimulants—crack cocaine, methamphetamine (i.e., crystal meth), or amphetamines (i.e., speed); (6) prescription drugs not used in the manner prescribed—benzodiazepines (e.g., Ativan, Xanax), opioids (including Diluadid, Oxycotin/Ocycondone), or sedatives (specifically Talwin & Ritalin, T3s & T4s); and (7) illicit opioids—heroin, heroin and cocaine (i.e., speedballs), morphine, or methadone.

Of note, although powder cocaine and crack cocaine are the same substance, we separated them into the groupings shown since they differ in terms of strength, routes of administration and ensuing effects on the body, as well as the socio-economics and criminality around use (i.e., crack cocaine is highly concentrated, smoked, cheaper, and more highly prosecuted) [57]. All of these factors are relevant to addiction potential and pertinent to exploring social disparity in substance use and associated effects on cART adherence among women with HIV. ‘Other party drugs’ and ‘other stimulants’ were grouped with powder cocaine and crack cocaine, respectively, owing to small cell sizes.

Concerning methadone, while it is legal for opioid substitution therapy and could be considered a misused prescription drug, we grouped it with illicit opioids because of its strong historic and current usage as a heroin substitute. Regarding cannabis, we did not distinguish between medical versus recreational use but explored self-reported motivations for use in post hoc analyses. Finally, since indicators only provided a measure of any use, we also explored frequency of use in post hoc analyses to assess the proportion of heavy users in each class.

Correlates of Latent Class Membership

Independent variables considered included: (1) adherence to cART (trichotomized as never/not currently on cART versus <95% (non-adherent) versus ≥95% (adherent), measured via self-report to a question asking women for their “best guess about how much medication they have taken in the last month”), (2) any experience of physical, sexual, verbal, or controlling violence in the past 3 months (yes vs. no), (3) age (<median (43 years) vs. ≥median [43]), (4) ethnicity (Indigenous vs. White vs. African, Caribbean, or Black vs. Other/multiple ethnicities), (5) sexual orientation (heterosexual vs. lesbian, gay, bisexual, two-spirited, or queer (LGBTQ), (6) annual household income (<$20,000 CAD vs. ≥$20,000 CAD, near the 2014 poverty line [58]), (7) sex work in the past 6 months (yes vs. no, with responses coded as “yes” if women reported receiving money, drugs, shelter, food, gifts, or other items in exchange for sex), (8) years since HIV diagnosis (<median (10.8) vs. ≥median (10.8)), and (9) resiliency (the Resilience Scale (RS-10), α = 0.90) [59], a 10-item scale (e.g., “When I’m in a difficult situation, I can usually find my way out of it”), scored on a 7-point scale from “Disagree” to “Agree”, summing to a range of 10–70, with higher scores indicating higher resilience. We dichotomized this scale at the median (<median, “lower resilience” vs. ≥median “higher resilience”) as it had a non-normal distribution (i.e., it was highly right-skewed). We employed a strict 95% cut-off definition of cART adherence for consistency and comparability with past research [60].

Analysis

Final Analytic Sample

Analyses were restricted to participants who completed the baseline questionnaire and provided valid responses to all indicators of latent class membership. Thus, the final analytic sample for LCA as well as descriptive and bivariable analyses was 1363 (96% of the total 1424 women enrolled). In multivariable analyses, an additional 153 participants who reported “don’t know” or “prefer not to answer” to selected covariates were excluded from the final model (n = 1210).

Latent Class Analysis

We modelled latent classes using PROC LCA for SAS (https://methodology.psu.edu) [61, 62] based on the seven substance use indicators described above, and examined solutions with two to six latent classes. Model identification for each solution was assessed by an expectation–maximization (EM) algorithm [61]. The maximum number of iterations for the EM algorithm was set to 1000. We performed 100 repetitions of model estimation for each solution, using 100 random sets of starting values, to ensure we found the global maximum log-likelihood (ML) solution. To select the best model, we considered interpretability of the classes and relied on information criteria: Akaike information criterion (AIC) [63], Bayesian information criterion (BIC) [64], consistent AIC (CAIC) [65] and adjusted BIC (aBIC) [66]. We used the posterior class membership probabilities from the LCA model estimation to weight women across the classes. In doing so, women were not assigned to one class but rather had a probability of being in each of the classes. While this multi-step method may attenuate associations (unlike the simultaneous approach that combines LCA with regression into a joint model), it allows for multivariable regression modelling with numerous covariates, which, in the one-step approach, can affect the LCA structure [67].

Descriptive, Bivariable, and Multivariable Analyses

Following LCA, sample characteristics were examined using frequencies and proportions. We then assessed the prevalence of covariates across the latent classes, using the Pearson χ2 to test for significant differences. Next, we used multinomial logistic regression to examine predictors of latent class membership, reporting adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Model selections were conducted using a backward stepwise elimination technique based on two criteria (AIC and Type III p-values), with the least significant variable dropped until the final model had the optimum (minimum) AIC [68]. This resulted in sexual orientation, ethnicity, income, violence, adherence, and resilience being included in the model.

Sex work was excluded from the final model as the referent latent class had only one woman currently involved in transactional sex, leading to highly unstable estimates and extremely wide 95% CIs. Time since diagnosis and age at interview were not selected for. We did, however, conduct a sensitivity analysis, including age in the model. The variance around each effect estimate for age included the null-value of ‘1’ and the AORs and 95% CIs for all other covariates remained similar. We also observed a slightly poorer model fit (i.e., higher AIC). Thus, we retained the original model (i.e., the one without age).

In presenting results, we adhered to the recent American Statistical Association statement on best practices that emphasized reporting both the best effect estimate and the 95% CI around that estimate, rather than p-values [69, 70]. We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS, North Carolina, United States) for all analyses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Overall, the sample included 41% women identifying as White, 30% as African, Caribbean, and Black, and 22% as Indigenous (Table 1). Median age was 43 (IQR = 35–50), and median time since HIV diagnosis was 10.8 years (IQR = 6–17). Thirteen percent identified as LGBTQ, 6% engaged in sex work in the 6 months prior to interview, 20% reported experiencing violence in the past 3 months, and nearly two-thirds (65%) had an annual household income <$20,000. The median resiliency score was 64 (IQR: 59–69). Finally, 17% were never/not currently on cART. Among those currently on cART, 73% had the optimum cART adherence level of ≥95%.

Substance Use Prevalence and Latent Class Models

The most commonly used substances were alcohol (n = 804, 59% of overall sample) and tobacco (n = 558, 43%) (Table 2). Cannabis use was reported by 25% (n = 346) of women. Among the remaining drug groupings, crack cocaine and other stimulants were most prevalent (14%, n = 185), followed by illicit opioids (8%, n = 103), powder cocaine and other party drugs (7%, n = 99), and misused prescription drugs (4%, n = 52). Crack (n = 148) and cocaine (n = 93) accounted for most of those coded within the groupings ‘crack cocaine and other stimulants’ and ‘powder cocaine and other party drugs’.

Table 3 shows the resulting goodness of fit statistics derived for the different latent class models in which all above drug types are included, and the percentage of seeds associated with the ML solution for each model. Although it had the lowest seed percentage (28/100), which indicates a complex latent variable, we considered 10% as a cut-off for inadequate model identification [49] and decided to select the 6-class model because of the scores associated with three fit statistics (i.e., lowest log-likelihood, G-squared, and AIC) and because it contained classes recognizable as distinct substance user groups.

Table 4 presents six latent classes associated with the selected model, showing their class membership and item response probabilities. We named these classes: (1) Abstainers (26.3%)—characterized by almost 100% of members reporting no current substance use; (2) Tobacco Users (8.8%)—the numerically smallest class, with almost 100% reporting smoking tobacco, but with few members using other substances; (3) Alcohol Users (31.9%)—the largest class, with almost all members reporting alcohol use combined with low (i.e., tobacco) or very low use of other substances; (4) Socially Acceptable Poly-substance Users (13.9%)—group members reported high levels of tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use; but low use of illicit substances; (5) Illicit Poly-substance Users (9.8%)—in addition to tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use, this group had high rates of cocaine and other party drug use (39%) as well as crack and other stimulant drug use (59%); and (6) Illicit Poly-substance Users of All Types (9.3%)—in addition to all aforementioned substances, these members also recorded high rates of prescription drug misuse (39%) and opioids (78%). Arranged in this sequence, LCA analysis indicates a substance use continuum, from none, through legal or socially acceptable substances, to illicit substances exemplified by crack, cocaine, and heroin, for instance, as well as increased poly-substance use.

Since the indicators making up these classes showed any use (not frequency of use), we investigated heavy use in post hoc bivariable analyses (data not shown). Binge drinking was most prevalent among Illicit Poly-substance Users (38%) and less common among Socially Acceptable Poly-substance Users (27%) and Alcohol Users (19%), suggesting heavy alcohol use co-occurred more frequently with those using illicit drugs. We also found that among those who smoked tobacco, most (71–78%) were heavy smokers (≥half pack per day) across all classes, indicating highly addicted smoking behaviors regardless of other substance use. Among those who used cocaine and crack, the most prevalent illicit drugs, Illicit Poly-substance Users of All Types reported higher rates of daily use of each substance (39%) versus Illicit Poly-substance Users (10% daily cocaine use, 19% daily crack use), signaling not just more types of drug use but also higher intensity drug use in the final latent class. While problematic cannabis use remained unmeasured, post hoc analyses showed cannabis use rationale varied markedly by latent class. Socially Acceptable Poly-substance Users who used cannabis were likely to report medical reasons for use (31% prescribed, 21% not prescribed) or both medical and recreational reasons (29%), as opposed to recreational reasons alone (19%). The opposite was true for Illicit Poly-substance Users of All Types who used cannabis: recreational purposes were most common (46%), versus prescription (9%) and non-prescription (18%) medical use and combined medical/recreational use (27%).

Bivariable and Multivariable Results

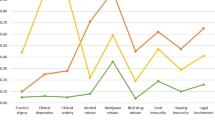

Bivariable Chi squared analyses, shown in Table 5, indicate considerable heterogeneity in latent class membership along several markers of social and clinical wellbeing. With the exception of Alcohol Users, the proportion of women identifying as Indigenous increased across each subsequent class, ranging from 12% of Abstainers to 45% of Illicit Poly-substance Users of All Types. A similar pattern was seen with LGBTQ women (range across classes 9–30%) and those reporting current sex work (1–35%) and recent violence (7–42%). A downward trend was observed in higher incomes (36–14% ≥$20,000) and higher resiliency scores (61–44% ≥median). Alcohol Users, however, were more likely to report incomes ≥$20,000 compared with Abstainers (48 vs. 36%) and less likely to report violence (7 vs. 15%), lower (i.e., below the median) resiliency scores (41 vs. 51%), and Indigenous ancestry (13 vs. 34%) compared with Tobacco Users. Ad hoc analyses showed that 78% of the Alcohol Users were non-binge drinkers in the past month (data not shown), indicating general (not heavy) alcohol use. Illicit Poly-substance Users of All Types were also more likely to be younger: 60% were <43 years, compared with 42–54% of all other classes. In terms of cART adherence, among those currently on treatment, Tobacco Users (81%) and Abstainers (79%) had the highest prevalence of being ≥95% adherent, followed by Alcohol Users (76%) and all classes of Poly-substance Users, ranging from a high of 68% for those using socially acceptable drugs to a low of 58% for those using all types of illicit drugs.

To explore group membership characteristics further we ran multinomial logistic regression analyses, using the Abstainers class as the referent group (Table 6). No independent associations were seen for women with Indigenous ancestry (versus White), while African, Caribbean, and Black women exhibited significantly lower adjusted odds of membership in all five latent classes. LGBTQ women had lower AORs for membership in some latent classes (i.e., Tobacco and Alcohol) relative to heterosexual women, but they had higher AORs in the class of Illicit Poly-substance User of All Types (1.91 (95% CI 1.01, 3.64)). A similarly complex pattern was seen for women with annual household incomes <$20,000: they were significantly more likely to be Tobacco and Illicit Poly-substance Users of All Types, but less likely to be Alcohol Users. Women with lower (i.e., below the median) resiliency scores were more likely to be members of the class of Illicit Poly-substance User of All Types, with a best estimate of 2.08 and effects ranging from 1.52 to 4.44. Violence was independently associated with membership in every latent class, with the high odds seen for Illicit (7.31 (95% CI 3.99, 13.39)) and Illicit-All Type (9.37 (95% CI 5.02, 17.48)) Poly-substance Users, compared with users of Alcohol (2.56 (95% CI 1.57, 4.19)), Tobacco (4.13 (95% CI 2.17, 7.86)), and Socially Acceptable Poly-substances (4.43 (95% CI 2.47, 7.94)). Finally, after adjusting for sexual orientation, ethnicity, income, violence, and resiliency, the strength of the association between sub-optimal adherence and substance use gradually increased across increasing classes of substance users, ranging from 1.16 (95% CI 0.60, 2.23) for Tobacco Users to 2.56 (95% CI 1.35, 4.88) for Illicit Poly-substance Users of All Types. The variance around the estimates excluded the null value of ‘1’ for the three poly-substance use classes only. Those never/not currently on cART (vs. adherent to cART) had reduced odds of membership in every substance use latent class.

Discussion

In this study, we used LCA to: (1) delineate specific substance use patterns; (2) identify social determinants of latent class membership and associations with sub-optimal cART adherence; and (3) assess results in light of the SAVA syndemic model. In the first regard, LCA produced a nuanced picture of multiple socially acceptable and illicit poly-substance use. Analysis showed important differences in social identities and economic positions and a trend of poorer adherence to cART across substance use classes, as well as increasing violence. Illicit Poly-substance Users of All Types were the most vulnerable group of women living with HIV as seen in associations with sexual minority status, poverty, and lower resilience and were least likely to realize optimal cART adherence. These findings add to the literature documenting the effects of SAVA on health outcomes for women living with HIV, with particular attention to complexity of substance use behaviours and their intersection with violence and the larger social contexts of oppression within which substance use and violence are embedded. In light of this, we argue that singular measures of substance use (e.g., any use versus no use) mask key nuances among women who use multiple forms of legal and illicit drugs as well as differing health and social realities.

In descriptive analyses, alcohol was the most commonly used substance (59%), though this was quite a bit lower than national statistics data showing (i.e., 74.3% of Canadian women have drank alcohol in the past year) [10] as well as data from international HIV cohorts (38–71%) [11, 71,72,73]. The prevalence of tobacco (43%) and cannabis (25%) use in this cohort was much higher than national estimates among females (13% and 6.2%, respectively), albeit comparable to other HIV cohorts [15, 74,75,76,77,78]. The same was true for rates of illicit drug use (4–14% in CHIWOS (depending on the substance) versus 1% nationally) [10, 79], with the most prevalent drugs being powder cocaine and crack cocaine, consistent with past research among women living with HIV [9, 80, 81]. Unlike previous research, however, we exposed patterns of poly-substance use using LCA. About one-third of women belonged to the Alcohol Users class, using alcohol almost exclusively. The second most prevalent latent class was Abstainers (26.3%), who had not used any of the 18 substances assessed. Remaining classes of roughly equal proportions included exclusive Tobacco Users (8.8%) and users of poly-substances including either Socially Acceptable Drugs (i.e., alcohol, marijuana, cannabis) (13.9%) or socially acceptable drugs combined with Illicit Drugs, which was divided into two latent classes (9–10%). These results provide a comprehensive snapshot of substance use among women living with HIV, adding to the LCA literature among other populations [45,46,47,48,49].

This study also linked substance use patterns to treatment sub-optimal adherence. Among women on cART, 73% of women reported more than 95% adherence, comparable to estimates from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) in the US [82]. It is worth noting, however, that lower levels of adherence can still achieve viral suppression and prevent drug resistance, although this depends on the potency of cART regimens and length of time suppressed [83, 84], among other factors (e.g., renal function, creatinine levels, body weight). While the majority of participants achieved the 95% adherence cut-off, this rate varied markedly by substance use: Abstainers, Tobacco Users, and Alcohol Users had the highest unadjusted rates (74–79%), while poly-substance users were least likely to adhere, including both Illicit Drug Users (58–63%) and Socially Accepted Poly-substance Users (68%). After adjusting for other factors, the best estimates corresponding to sub-optimal adherence increased across increasing types of drug use, from Tobacco Users to Illicit Poly-substance Users of All Types, though was only statistically significant for the three poly-substance use classes. This contradicts past research showing a significant association between sub-optimal adherence and tobacco use [4] and alcohol [5, 12, 13], but supports findings concerning illicit drugs like cocaine [7] and crack [9]. It also brings insight to the impact of multiple socially acceptable drugs (i.e., tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana combined). Those never/not currently on cART (versus adherent to cART) had reduced odds of membership in every substance use latent class. While current guidelines suggest all individuals should be on treatment [85], there are a variety of reasons women may not be taking cART including levels of current health and personal autonomy. These results are important and bear future study.

Results also demonstrated how substance use patterns intersect with several social factors, which may help to explain why some women are less adherent to treatment. For example, 50% of women identifying as African, Caribbean, and Black were Abstainers and 44% Alcohol Users, leaving only 6% distributed across the remaining latent classes. Recent (past 3 months) violence was also particularly striking, affecting 20% of the cohort overall, but just 7% of Abstainers versus 36–42% of Illicit Drug Users. This is comparable to prevalence estimates of violence from some cohorts [21] but lower than others [22]. Importantly, the AORs reported in this study add to evidence linking violence and substance use epidemics [21, 23, 24], particularly among heavy users of substances, sex workers [25,26,27], and young Indigenous women [28]. Indeed, our study found unadjusted associations between substance use and sex work and younger age (although these variables were not selected for in the final model owing to low sample size in some cells), along with adjusted associations with ethnicity, lower income, LGBTQ identity, and lower resilience. With the exception of sexual minority status (to our knowledge), each of these factors have been implicated in viral suppression and treatment adherence in past research, with both their independent [22, 28, 43] and combined (SAVA) effects documented [37]. It is worth noting that even after adjusting for variables marking social marginalization, financial isolation, violence, and resilience, sub-optimal adherence was still independently and significantly associated with poly-substance use (whether socially acceptable or illicit). This may reflect confounders unaccounted for in the final multivariable model (e.g., housing instability, food insecurity). Regardless, findings provide clear evidence of the clustering of “mutually enhancing epidemics” or syndemics, which emerge from “harmful social conditions and injurious social connections” [40].

There are limitations to this study. Self-reporting of substance use may have been influenced by social desirability bias, resulting in substance use underreporting. However, study interviewers were peers (women living with HIV), who may have improved the quality of data collection through increased trust and rapport with participants [86]. Also, data were derived from a cross-sectional survey, necessitating longitudinal inquiries such as latent transition analyses to evaluate these relationships over time [49]. Additionally, our LCA substance use indicators were dichotomous measures, though we did examine frequency and intensity of use in ad-hoc analyses. We also found significant associations with cART adherence, violence, and other social determinants of health, suggesting that our measure of exposure meaningfully captured substance use behaviors with negative health consequences. Many factors contributing to social marginalization including intersectional stigma related to drug use, sex work, and HIV were not investigated in this study and should be examined in future research. The study’s strengths include its use of a large and multi-site sample of women living with HIV, an under-researched population in Canada. In addition, to our knowledge, it is the first study to analyze substance use patterns of women living with HIV by combining LCA and the SAVA theoretical framework, as opposed to more traditional approaches employing one broad substance use indicator in isolation from social contexts. Results offer a new methodological direction for researchers focused on the social dimensions and effects of SAVA among women living with HIV and also have important implications for care providers.

As women living with HIV have multiple intersecting needs and concerns, supporting their health requires integrated care protocols and referral systems. Low-barrier dispensation of cART to those who use substances is an essential component. The effect of Maximally Assisted Therapy on supporting HIV treatment adherence has been documented in Canada [87], along with other similar programs (e.g., Directly Observed Therapy) in other jurisdictions [88,89,90]. Linking daily cART administration to daily witnessed methadone may be particularly promising for those using heroin or other opioids [91]. Integrating these interventions with drug harm reduction counseling and programming onsite is also key, including the creation of spaces for people to use drugs and, at the same time, access a range of essential health and social services [92]. Key elements of such care programs include fostering a safe and welcoming environment free from stigma and judgement, meaningfully involving those affected by substance use as equal partners in service planning and delivery, and tailoring supports to individuals’ unique needs [93]. Our findings also underscore the importance of reducing harms across the social determinants of women’s health, with particular attention to violence, poverty, and other social epidemics marginalizing women [94]. Culturally-relevant, strength-based approaches that focus on building resiliency may be helpful [43]. Supporting women with HIV who use substances is also challenged in Canada by laws that criminalize drug use [95], and greater attention to creating more enabling legal and societal structures, not just individual supports, are needed in research and public health practice.

Conclusions

Substance use among women living with HIV is varied and complex, with multiple causes and consequences. This study delineated complex substance use patterns via LCA and linked these patterns, empirically and theoretically using a SAVA lens, to cART sub-optimal adherence and syndemic factors including violence, poverty, and sexual minority status. Results showed women experiencing current violence and sub-optimal adherence had higher odds of membership in more illicit drug use latent classes. Based on these findings, research and support for women living with HIV who use substances must consider relationships between substance use, violence, and HIV/AIDS and address these issues concurrently–not just to support treatment adherence but, more importantly, to improve safety and wellbeing for women living with HIV.

References

Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112(3):178–93.

Lucas GM. Substance abuse, adherence with antiretroviral therapy, and clinical outcomes among HIV-infected individuals. Life Sci. 2011;88(21):948–52.

Slawson G, Milloy M, Balneaves L, Simo A, Guillemi S, Hogg R, et al. High-intensity cannabis use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people who use illicit drugs in a Canadian setting. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):120–7.

Shuter J, Bernstein SL. Cigarette smoking is an independent predictor of nonadherence in HIV-infected individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(4):731–6.

Rosen M, Black A, Arnsten J, Goggin K, Remien R, Simoni J, et al. Association between use of specific drugs and antiretroviral adherence: findings from MACH 14. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):142–7.

Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Grasso C, Crane HM, Safren SA, Kitahata MM, et al. Substance use among HIV-infected patients engaged in primary care in the United States: findings from the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems cohort. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1457–67.

Hinkin CH, Barclay TR, Castellon SA, Levine AJ, Durvasula RS, Marion SD, et al. Drug use and medication adherence among HIV-1 infected individuals. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(2):185–94.

Azar P, Wood E, Nguyen P, Luma M, Montaner J, Kerr T, et al. Drug use patterns associated with risk of non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive illicit drug users in a Canadian setting: a longitudinal analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):193.

Sharpe TT, Lee LM, Nakashima AK, Elam-Evans LD, Fleming PL. Crack cocaine use and adherence to antiretroviral treatment among HIV-infected black women. J Community Health. 2004;29(2):117–27.

Health Canada. Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Monitoring Survey: Summary of Results for 2011. 2011. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/drugs-drogues/stat/_2011/summary-sommaire-eng.php-share.

Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, McNerney M, White D, Kalichman MO, et al. Viral suppression and antiretroviral medication adherence among alcohol using HIV-positive adults. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21(5):811–20.

Chander LB, Moore R. Hazardous alcohol use: a risk factor for non-adherence and lack of suppression in HIV infection (1999). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndromes. 2006;43(4):411.

Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, Simoni JM. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis (1999). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndromes. 2009;52(2):180.

Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, Sales S, Page JB, Campa A. Alcohol use accelerates HIV disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2010;26(5):511–8.

Bonn-Miller MO, Oser ML, Bucossi MM, Trafton JA. Cannabis use and HIV antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-related symptoms. J Behav Med. 2014;37(1):1–10.

Lake S, Kerr T, Capler R, Shoveller J, Montaner J, Milloy MJ. High-intensity cannabis use and HIV clinical outcomes among HIV-positive people who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;42:63–70.

Porter K, Babiker A, Bhaskaran K, Darbyshire J, Pezzotti P, Porter K, et al. Determinants of survival following HIV-1 seroconversion after the introduction of HAART. Lancet. 2003;362(9392):1267–74.

Grigoryan A, Hall HI, Durant T, Wei X. Late HIV diagnosis and determinants of progression to AIDS or death after HIV diagnosis among injection drug users, 33 US States, 1996–2004. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(2):e4445.

Carrico AW. Substance use and HIV disease progression in the HAART era: implications for the primary prevention of HIV. Life Sci. 2011;88(21):940–7.

Machtinger E, Wilson T, Haberer JE, Weiss D. Psychological trauma and PTSD in HIV-positive women: a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2091–100.

Borwein A, Chan K, Palmer A, Miller C, Montaner J, Hogg R. Violence among a cohort of HIV-positive women on antiretroviral therapy in British Columbia, Canada. Oral session presented at 1st International Workshop on HIV and Women 2011, January.

Trimble DD, Nava A, McFarlane J. Intimate partner violence and antiretroviral adherence among women receiving care in an urban Southeastern Texas HIV clinic. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24(4):331–40.

Gruskin L, Gange SJ, Celentano D, Schuman P, Moore JS, Zierler S, et al. Incidence of violence against HIV-infected and uninfected women: findings from the HIV Epidemiology Research (HER) Study. J Urban Health. 2002;79(4):512–24.

Bedimo AL, Kissinger P, Bessinger R. History of sexual abuse among HIV-infected women. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8(5):332–5.

Shannon K, Kerr T, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Montaner JS, Tyndall MW. Prevalence and structural correlates of gender based violence among a prospective cohort of female sex workers. BMJ. 2009;339:2939–47.

El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, Go H, Hill J. HIV and intimate partner violence among methadone-maintained women in New York City. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(1):171–83.

El-Bassel N, Witte S, Wada T, Gilbert L, Wallace J. Correlates of partner violence among female street-based sex workers: substance abuse, history of childhood abuse, and HIV risks. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2001;15(1):41–51.

Pearce ME, Christian WM, Patterson K, Norris K, Moniruzzaman A, Craib KJP, et al. The cedar project: historical trauma, sexual abuse and HIV risk among young aboriginal people who use injection and non-injection drugs in two Canadian cities. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(11):2185–94.

Berger. Workable sisterhood: the political journey of stigmatized women with HIV/AIDS. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2010.

Logie C, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy M. HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: a qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11):e1001124.

Azim T, Bontell I, Strathdee SA. Women, drugs and HIV. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(1):S16–21.

Campbell JC, Baty M, Ghandour RM, Stockman JK, Francisco L, Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: a review. Int J Injury Control Saf Promot. 2008;15(4):221–31.

Hatcher AM, Smout EM, Turan JM, Christofides N, Stöckl H. Intimate partner violence and engagement in HIV care and treatment among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2015;29(16):2183–94.

Schafer KR, Brant J, Gupta S, Thorpe J, Winstead-Derlega C, Pinkerton R, et al. Intimate partner violence: a predictor of worse HIV outcomes and engagement in care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(6):356–65.

Machtinger E, Haberer J, Wilson T, Weiss D. Recent trauma is associated with antiretroviral failure and HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-positive women and female-identified transgenders. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2160–70.

Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: a literature review of the syndemic. J Women’s Health. 2011;20(7):991–1006.

Sullivan KA, Messer LC, Quinlivan EB. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV/AIDS (SAVA) syndemic effects on viral suppression among HIV positive women of color. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(S1):S42–8.

Singer M. A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inq Creative Sociol. 1996;24(2):99–110.

Singer M. AIDS and the health crisis of the US urban poor; the perspective of critical medical anthropology. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(7):931–48.

Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17(4):423–41.

Batchelder AW, Lounsbury DW, Palma A, Carrico A, Pachankis J, Schoenbaum E, et al. Importance of substance use and violence in psychosocial syndemics among women with and at-risk for HIV. AIDS Care. 2016;28(10):1316–20.

Koblin BA, Grant S, Frye V, Superak H, Sanchez B, Lucy D, et al. HIV sexual risk and syndemics among women in three urban areas in the United States: analysis from HVTN 906. J Urban Health. 2015;92(3):572–83.

Dale S, Cohen M, Weber K, Cruise R, Kelso G, Brody L. Abuse and resilience in relation to HAART medication adherence and HIV viral load among women with HIV in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014;28(3):136–43.

Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis: with applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Hoboken: Wiley; 2013.

Sunderland M, Chalmers J, McKetin R, Bright D. Typologies of alcohol consumption on a saturday night among young adults. Alcoholism. 2014;38(6):1745–52.

Noor SW, Ross MW, Lai D, Risser JM. Use of latent class analysis approach to describe drug and sexual HIV risk patterns among injection drug users in Houston, Texas. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):276–83.

McCarty-Caplan D, Jantz I, Swartz J. MSM and drug use: a latent class analysis of drug use and related sexual risk behaviors. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(7):1339–51.

Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Greene GJ, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. Prevalence and patterns of smoking, alcohol use, and illicit drug use in young men who have sex with men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;141:65–71.

Lanza ST, Bray BC. Transitions in drug use among high-risk women: an application of latent class and latent transition analysis. Adv Appl Stat Sci. 2010;3(2):203–35.

Loutfy M, Greene S, Kennedy VL, Lewis J, Thomas-Pavanel J, Conway T, et al. Establishing the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS): operationalizing Community-based Research in a Large National Quantitative Study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):101–10.

Loutfy M dPA, O’Brien N, Thomas-Pavanel J, Carter A, Proulx-Boucher K, Beaver K, Nicholson V, Colley G, Sereda P, Hogg RS, Kaida A, CHIWOS Research Team. The Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS): an evaluation of women-centred HIV care (WCC). 5th International Workshop on HIV and Women; Seattle, WAFebruary 21-22nd, 2015.

Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19(1):173–202.

Raphael D. Social determinants of health: Canadian perspectives. 2nd ed. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2009.

Benoit C, Shumka L. Gendering the population health perspective: fundamental determinants of women’s health. Final report prepared for the Women’s Health Research Network. Vancouver, BC; 2007.

De Reus LA, Few AL, Blume LB. Multicultural and critical race feminisms: theorizing families in the third wave. Sourceb Fam Theory Res. 2005. doi:10.4135/9781412990172.n18.

Webster K, Carter A, Proulx-Boucher K, Dubuc D, Nicholson V, Beaver K, et al. Strategies for recruiting women living with HIV in community-based research: Lessons from Canada Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. Accepted.

Palamar JJ, Davies S, Ompad DC, Cleland CM, Weitzman M. Powder cocaine and crack use in the United States: an examination of risk for arrest and socioeconomic disparities in use. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2015;149:108–16.

Statistics Canada. Low income lines, 2013-2014: Update Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada; 2013.

Wagnild G, Young H. Development and psychometric validation of the resilience scale. J Nurs Meas. 1993;1:165–78.

Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. AIDS. 2002;16(2):269–77.

Lanza ST, Collins LM, Lemmon DR, Schafer JL. PROC LCA: a SAS procedure for latent class analysis. Struct Equ Model. 2007;14(4):671–94.

Lanza ST, Dziak JJ, Huang L, Xu S, Collins LM. PROC LCA & PROC LTA user’s guide (Version 1.3.2). University Park: The Methodology Center, Pennsylvania State University; 2015.

Akaike H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):317–32.

Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6(2):461–4.

Bozdogan H. Model selection and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC): the general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):345–70.

Sclove SL. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):333–43.

Vermunt JK. Latent class modeling with covariates: two improved three-step approaches. Polit Anal. 2010;18(4):450–69.

Lima VD, Geller J, Bangsberg DR, Patterson TL, Daniel M, Kerr T, et al. The effect of adherence on the association between depressive symptoms and mortality among HIV-infected individuals first initiating HAART. AIDS. 2007;21(9):1175–83.

Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA’s statement on p-values: context, process, and purpose. The American Statistician. 2016.

Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: an introduction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, London AS, Caetano R, Burnam MA, et al. The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(2):179–86.

Hutton HE, McCaul ME, Chander G, Jenckes MW, Nollen C, Sharp VL, et al. Alcohol use, anal sex, and other risky sexual behaviors among HIV-infected women and men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1694–704.

Chander Josephs J, Fleishman J, Korthuis P, Gaist P, Hellinger J, et al. Alcohol use among HIV-infected persons in care: results of a multi-site survey. HIV Med. 2008;9(4):196–202.

Webb MS, Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC. Cigarette smoking among HIV + men and women: examining health, substance use, and psychosocial correlates across the smoking spectrum. J Behav Med. 2007;30(5):371–83.

Lifson AR, Neuhaus J, Arribas JR, van den Berg-Wolf M, Labriola AM, Read TR. Smoking-related health risks among persons with HIV in the strategies for management of antiretroviral therapy clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1896–903.

Helleberg M, Afzal S, Kronborg G, Larsen CS, Pedersen G, Gerstoft J, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking among HIV-1–infected individuals: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(5):727–34.

Hile SJ, Feldman MB, Alexy ER, Irvine MK. Recent tobacco smoking is associated with poor HIV medical outcomes among HIV-infected individuals in New York. AIDS Behav. 2016. doi:10.1007/s10461-015-1273-x.

Prentiss D, Power R, Balmas G, Tzuang G, Israelski DM. Patterns of marijuana use among patients with HIV/AIDS followed in a public health care setting. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndromes. 2004;35(1):38–45.

Reid JL, Hammond D, Rynard VL, Burkhalter R. Tobacco use in Canada: patterns and trends. 2015th ed. Waterloo: Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, University of Waterloo; 2015.

Kuo I, Golin CE, Wang J, Haley DF, Hughes J, Mannheimer S, et al. Substance use patterns and factors associated with changes over time in a cohort of heterosexual women at risk for HIV acquisition in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;139:93–9.

Marquez C, Mitchell SJ, Hare CB, John M, Klausner JD. Methamphetamine use, sexual activity, patient–provider communication, and medication adherence among HIV-infected patients in care, San Francisco 2004–2006. AIDS Care. 2009;21(5):575–82.

Kapadia F, Vlahov D, Wu Y, Cohen MH, Greenblatt RM, Howard AA, et al. Impact of drug abuse treatment modalities on adherence to ART/HAART among a cohort of HIV seropositive women. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34(2):161–70.

Bangsberg DR. Preventing HIV antiretroviral resistance through better monitoring of treatment adherence. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(Supplement 3):S272–8.

Lima VD, Bangsberg DR, Harrigan PR, Deeks SG, Yip B, Hogg RS, et al. Risk of viral failure declines with duration of suppression on HAART, irrespective of adherence level. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndromes. 2010;55(4):460.

Günthard HF, Saag MS, Benson CA, Rio C, Eron JJ, Gallant JE. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2016 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA Panel. JAMA. 2016;2016:316.

Brizay U, Golob L, Globerman J, Gogolishvili D, Bird M, Rios-Ellis B, et al. Community-academic partnerships in HIV-related research: a systematic literature review of theory and practice. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1):19354.

Parashar S, Palmer AK, O’Brien N, Chan K, Shen A, Coulter S, et al. Sticking to it: the effect of maximally assisted therapy on antiretroviral treatment adherence among individuals living with HIV who are unstably housed. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1612.

Maru DS-R, Bruce RD, Walton M, Mezger JA, Springer SA, Shield D, et al. Initiation, adherence, and retention in a randomized controlled trial of directly administered antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(2):284–93.

Macalino GE, Hogan JW, Mitty JA, Bazerman LB, DeLong AK, Loewenthal H, et al. A randomized clinical trial of community-based directly observed therapy as an adherence intervention for HAART among substance users. AIDS. 2007;21(11):1473–7.

Altice FL, Maru DS-R, Bruce RD, Springer SA, Friedland GH. Superiority of directly administered antiretroviral therapy over self-administered therapy among HIV-infected drug users: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(6):770–8.

Lappalainen L, Nolan S, Dobrer S, Puscas C, Montaner J, Ahamad K, et al. Dose–response relationship between methadone dose and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive people who use illicit opioids. Addiction. 2015;110(8):1330–9.

Vancouver Coastal Health. Insite - Supervised Injection Site 2016. http://supervisedinjection.vch.ca.

British Columbia Ministry of Health. Integrated models of primary care and mental health & substance use care in the community: literature review and guiding document. Vancouver: British Columbia Ministry of Health; 2012.

British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health. Women-centred harm reduction: gendering the national framework. Vancouver: British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health; 2012.

Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. The challenges in managing HIV in people who use drugs. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2015;28(1):10.

Acknowledgements

The Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS) Research Team would like to especially thank all of the women living with HIV who participate in this research. We also thank the entire national team of Co-Investigators, Collaborators, and Peer Research Associates. We would like to acknowledge the national Steering Committee, the three provincial Community Advisory Boards, the national CHIWOS Aboriginal Advisory Board, and our partnering organizations for supporting the study, especially those who provide interview space and support to our Peer Research Associates.

Funding

CHIWOS is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, MOP111041); the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network (CTN 262); the Ontario HIV Treatment Network (OHTN); and the Academic Health Science Centres (AHSC) Alternative Funding Plans (AFP) Innovation Fund. AC received support from a CIHR Doctoral Award. AdP received support from Fonds de Recherche du Quebéc – Santé (FRQS) (Chercheur-boursier clinicien – Junior 1). AK received salary support through a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Global Perspectives on HIV and Sexual and Reproductive Health. M-JM is supported in part by the United States National Institutes of Health (R01-DA0251525), a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and a New Investigator Award from CIHR. His institution has received unstructured funding to support his research from NG Biomed, Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Additional research team members and affiliated institutions are listed below in Appendix.

Appendix

Appendix

Chiwos Research Team

British Columbia Aranka Anema (University of British Columbia), Denise Becker (Positive Living Society of British Columbia), Lori Brotto (University of British Columbia), Allison Carter (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and Simon Fraser University), Claudette Cardinal (Simon Fraser University), Guillaume Colley (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Erin Ding (British Columbia Centre for Excellence), Janice Duddy (Pacific AIDS Network), Nada Gataric (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Robert S. Hogg (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and Simon Fraser University), Terry Howard (Positive Living Society of British Columbia), Shahab Jabbari (British Columbia Centre for Excellence), Evin Jones (Pacific AIDS Network), Mary Kestler (Oak Tree Clinic, BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre), Andrea Langlois (Pacific AIDS Network), Viviane Lima (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Elisa Lloyd-Smith (Providence Health Care), Melissa Medjuck (Positive Women’s Network), Cari Miller (Simon Fraser University), Deborah Money (Women’s Health Research Institute), Valerie Nicholson (Simon Fraser University), Gina Ogilvie (British Columbia Centre for Disease Control), Sophie Patterson (Simon Fraser University), Neora Pick (Oak Tree Clinic, BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre), Eric Roth (University of Victoria), Kate Salters (Simon Fraser University), Margarite Sanchez (ViVA, Positive Living Society of British Columbia), Jacquie Sas (CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network), Paul Sereda (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Marcie Summers (Positive Women’s Network), Christina Tom (Simon Fraser University, BC), Clara Wang (British Columbia Centre for Excellence), Kath Webster (Simon Fraser University), Wendy Zhang (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS).

Ontario Rahma Abdul-Noor (Women’s College Research Institute), Jonathan Angel (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute), Fatimatou Barry (Women’s College Research Institute), Greta Bauer (University of Western Ontario), Kerrigan Beaver (Women’s College Research Institute), Anita Benoit (Women’s College Research Institute), Breklyn Bertozzi (Women’s College Research Institute), Sheila Borton (Women’s College Research Institute), Tammy Bourque (Women’s College Research Institute), Jason Brophy (Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario), Ann Burchell (Ontario HIV Treatment Network), Allison Carlson (Women’s College Research Institute), Lynne Cioppa (Women’s College Research Institute), Jeffrey Cohen (Windsor Regional Hospital), Tracey Conway (Women’s College Research Institute), Curtis Cooper (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute), Jasmine Cotnam (Women’s College Research Institute), Janette Cousineau (Women’s College Research Institute), Marisol Desbiens (Women’s College Research Institute), Annette Fraleigh (Women’s College Research Institute), Brenda Gagnier (Women’s College Research Institute), Claudine Gasingirwa (Women’s College Research Institute), Saara Greene (McMaster University), Trevor Hart (Ryerson University), Shazia Islam (Women’s College Research Institute), Charu Kaushic (McMaster University), Logan Kennedy (Women’s College Research Institute), Desiree Kerr (Women’s College Research Institute), Maxime Kiboyogo (McGill University Health Centre), Gladys Kwaramba (Women’s College Research Institute), Lynne Leonard (University of Ottawa), Johanna Lewis (Women’s College Research Institute), Carmen Logie (University of Toronto), Shari Margolese (Women’s College Research Institute), Marvelous Muchenje (Women’s Health in Women’s Hands), Mary (Muthoni) Ndung'u (Women’s College Research Institute), Kelly O’Brien (University of Toronto), Charlene Ouellette (Women’s College Research Institute), Jeff Powis (Toronto East General Hospital), Corinna Quan (Windsor Regional Hospital), Janet Raboud (Ontario HIV Treatment Network), Anita Rachlis (Sunnybrook Health Science Centre), Edward Ralph (St. Joseph’s Health Care), Sean Rourke (Ontario HIV Treatment Network), Sergio Rueda (Ontario HIV Treatment Network), Roger Sandre (Haven Clinic), Fiona Smaill (McMaster University), Stephanie Smith (Women’s College Research Institute), Tsitsi Tigere (Women’s College Research Institute), Wangari Tharao (Women’s Health in Women’s Hands), Sharon Walmsley (Toronto General Research Institute), Wendy Wobeser (Kingston University), Jessica Yee (Native Youth Sexual Health Network), Mark Yudin (St-Michael’s Hospital).

Québec Dada Mamvula Bakombo (McGill University Health Centre), Jean-Guy Baril (Université de Montréal), Nora Butler Burke (University Concordia), Pierrette Clément (McGill University Health Center), Janice Dayle, (McGill University Health Centre), Danièle Dubuc, (McGill University Health Centre), Mylène Fernet (Université du Québec à Montréal), Danielle Groleau (McGill University), Ken Montheith (COCQ-SIDA), Marina Klein (McGill University Health Centre), Carrie Martin (Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal), Lyne Massie, (Université de Québec à Montréal), Brigitte Ménard, (McGill University Health Centre), Nadia O'Brien (McGill University Health Centre and Université de Montréal), Joanne Otis (Université du Québec à Montréal), Doris Peltier (Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network), Alie Pierre, (McGill University Health Centre), Karène Proulx-Boucher (McGill University Health Centre), Danielle Rouleau (Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal), Édénia Savoie (McGill University Health Centre), Cécile Tremblay (Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal), Benoit Trottier (Clinique l’Actuel), Sylvie Trottier (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec), Christos Tsoukas (McGill University Health Centre).

Other Canadian provinces or international jurisdictions Jacqueline Gahagan (Dalhousie University), Catherine Hankins (University of Amsterdam and McGill University), Renee Masching (Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network), Susanna Ogunnaike-Cooke (Public Health Agency of Canada).

All other CHIWOS Research Team Members who wish to remain anonymous.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carter, A., Roth, E.A., Ding, E. et al. Substance Use, Violence, and Antiretroviral Adherence: A Latent Class Analysis of Women Living with HIV in Canada. AIDS Behav 22, 971–985 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1863-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1863-x