Abstract

Maternal anxiety is common during the perinatal period, and despite the negative outcomes of anxiety on the mother and infant, its treatment has received limited attention. This paper describes the first review of psychological interventions for clinical anxiety during the perinatal period. A systematic search was carried out of six electronic databases. Five studies which evaluated psychological interventions for clinical anxiety in perinatal women were identified. Of the five studies included, four were open trials and one was a randomised controlled trial. Three studies evaluated group-based interventions; one study evaluated an online-delivered intervention; and one study a combined pharmacologic-psychological intervention. All participants demonstrated significant reductions in anxiety symptom severity from pre- to post-treatment. However, this review was limited to published literature evaluating treatments for clinical anxiety in perinatal women, which may have excluded important intervention studies and prevention programs, and unpublished literature. This review identifies an area of research that needs urgent attention, as very few studies have evaluated psychological treatments for perinatal anxiety. The studies included in this review demonstrate that symptoms of anxiety during the perinatal period appear to improve during treatment. Future research is needed to establish the efficacy of perinatal anxiety interventions in randomised controlled trials, whether reductions persist long term and whether benefits extend to other outcomes for the mother, infant and family.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The perinatal period, from pregnancy through to 12 months postpartum, represents a time of increased vulnerability to maternal mental health problems (Biaggi et al. 2016; O’Hara and Wisner 2014). Anxiety and depressive disorders are most common with rates significantly higher in pregnant and postpartum women than in the general adult population (Dennis et al. 2017). Although there has been considerable focus on treating maternal depression during the perinatal period (e.g. Sockol et al. 2011), anxiety has received limited attention despite similar, if not higher, prevalence rates and negative maternal-infant outcomes if left untreated.

Between 9 and 23% of women will experience clinical levels of anxiety during pregnancy (i.e. antenatal period) and 11–21% during the postpartum period (Dennis et al. 2017; Fairbrother et al. 2016), with 8.5% of postpartum mothers estimated to meet criteria for one or more anxiety disorders (Goodman et al. 2016). Anxiety symptoms occur on a continuum of severity with ‘clinical levels’ (i.e. moderate to severe range) representing anxiety at its most distressing and persistent (Goodman et al. 2016; Milgrom and Gemmill 2015). Anxiety during this period is associated with adverse effects on both the mother and infant (e.g. detrimental to the mother-infant relationship; increased risk of obstetrical complications and child developmental problems; Glasheen et al. 2010; Stein et al. 2014). Untreated antenatal anxiety is also one of the strongest predictors of maternal postpartum depression (Austin et al. 2007; Milgrom et al. 2008).

While there is a great deal of evidence for the effectiveness of psychological treatments, particularly cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), for anxiety disorders in the general adult population (Hofmann and Smits 2008; Stewart and Chambless 2009), the perinatal period presents unique issues and considerations for the treatment of anxiety (e.g. fears of childbirth; intrusive thoughts of harm to baby; Ross and McLean 2006). To address these issues, psychological treatments tailored for the perinatal period have been developed. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the evidence for perinatal-specific psychological interventions for the treatment of clinical anxiety.

The only previous review of this literature, conducted by Goodman et al. (2016), focused on anxiety disorders in postpartum women. The review found two pilot studies of treatment interventions for postpartum anxiety disorders. In one study, Green et al. (2015) found a 6-week group CBT program for women with a primary anxiety disorder significantly improved worry and depression symptoms from pre- to post-treatment. In the second study, Challacombe and Salkovskis (2011) showed significant improvements in symptoms (self-report and clinician ratings) of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in a case series of an intensive CBT program, delivered in sessions of 2 to 3 h over a 2-week period, for postpartum women with OCD.

Notably, the review by Goodman et al. (2016) focused solely on women who met diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder, rather than those with clinical levels of anxiety symptoms. Despite clinical diagnostic interviews being the current ‘gold standard’ of measuring mental health problems, diagnostic measures may not account for all perinatal-specific problems or difficulties (Ayers et al. 2015). Further, studies investigating treatment interventions in clinical samples often rely on self-report anxiety symptom measures rather than clinician-administered diagnostic interviews (Goodman et al. 2016; Grant et al. 2008). Not all women will meet diagnostic criteria; yet, a substantial proportion will experience clinical levels of anxiety symptoms and similar levels of distress and disability (Milgrom and Gemmill 2015). A broader systematic review is therefore needed to examine the effect of psychological treatments on the reduction of clinical levels of anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders. While subthreshold symptoms of anxiety are also often considered important by clinicians and researchers, interventions evaluated in nonclinical samples cannot be generalised to women experiencing clinical levels of anxiety which differ qualitatively and in severity to subthreshold symptoms (Goodman et al. 2016).

In addition, the previous review by Goodman et al. (2016) only focused on postpartum anxiety disorders and did not review treatments for the antenatal (i.e. pregnancy) period. While pregnancy has historically been considered a ‘protective’ factor against the development of maternal mental health problems (e.g. Biaggi et al. 2016), recent prevalence rates estimate more women experience an anxiety disorder during pregnancy (18%) than postpartum (10%; Dennis et al. 2017). There is also growing evidence that antenatal exposure to anxiety can have negative effects on offspring development up to adolescence (e.g. Betts et al. 2014). Given women prefer nonpharmacological treatment interventions due to potential concerns about fetal and infant health outcomes associated with the use of medication (e.g. Shaila Misri and Kendrick 2007), evaluating the efficacy of psychological interventions for antenatal anxiety is an important area of focus that warrants investigation. To date, research has shown a positive impact of CBT-based group treatment for antenatal anxiety disorders (e.g. blood injection phobia; Lilliecreutz et al. 2010) and mindfulness-based group cognitive therapy for clinical levels of antenatal anxiety symptoms (Goodman et al. 2014).

This study aimed to conduct a comprehensive review of psychological interventions for the treatment of clinical levels of anxiety in women during the perinatal period. We also sought to determine the effect of improvements in symptoms on maternal-infant outcomes and examine adherence rates and program satisfaction.

Materials and methods

Inclusion/eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were

-

1.

Participants: Women aged over 18 years, pregnant or in the postpartum period (defined as ≤ 12 months after childbirth) who met criteria for a clinical anxiety disorder according to a diagnostic interview (e.g. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), First and Gibbon 2004) or met clinical cut-off scoresFootnote 1 on a validated self-report measure of anxiety (e.g. State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Spielberger et al. 1970).

-

2.

Interventions: Psychotherapeutic interventions of any psychological treatment modality (e.g. CBT; behavioural activation) or delivery mode (e.g. group, face-to-face) specifically targeted at reducing maternal anxiety symptoms during the perinatal period were included. Interventions targeting ‘worry’ and ‘perinatal-specific anxiety’ (e.g. fear of childbirth) were included if a validated measure of the construct with clear cut-off scores for clinical levels of symptoms were used (e.g. Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire (W-DEQ), Wijma et al. 1998). Self-guided and therapist- or clinician-assisted interventions were included, as were blended interventions (e.g. computerised intervention combined with face-to-face therapy).

-

3.

Comparisons and outcomes: Studies were included that reported at least one validated self-report or clinician-administered measure of anxiety at pre-treatment (baseline) and post-treatment in order to determine treatment effects. Because many of the studies used different instruments to measure anxiety, we used the primary outcome as reported by the study investigators.

-

4.

Study design: Studies published in English in a peer-reviewed journal. Randomised controlled trials (RCT), uncontrolled (open) trials, and feasibility studies with a pre-post-study design were included.

Excluded studies

We excluded (1) studies of psychosocial interventions that did not explicitly target perinatal anxiety symptoms (e.g. general wellbeing; stress management), (2) studies that did not report pre-post anxiety treatment effects, and (3) studies that focused on populations under age 18 and greater than 12 months postpartum. Qualitative studies, case studies and case series were excluded. Protocols, conference abstracts and dissertations were excluded if study results were not published or ‘in press’.

Identification and selection of studies

Relevant studies were identified through comprehensive systematic searches of electronic databases, up to 5 May 2017. Databases included: PsycINFO, Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and PubMed, CINAHL and Maternity and Infant Care. A combination of perinatal (e.g. pregnancy), anxiety (e.g. anxiety) and intervention terms (e.g. treatment) were used to search databases (see Appendix A).

After duplicates were removed, two authors (SL, MW) independently screened all titles and abstracts for relevance to this study. Studies found ineligible based on title/abstract were discarded (e.g. fertility studies). All eligible papers were retrieved for full-text screening and independently reviewed by authors (SL, AJ, HH) to assess further eligibility for inclusion. Those studies not meeting inclusion criteria at full-text review were discarded (e.g. nonclinical samples; depression interventions; studies not published in English). Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consultation with author JN.

Results

Study selection

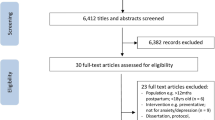

Figure 1 presents the flow chart. Database searches yielded 9207 studies; of these, 35 full texts were screened. After full text review, eight manuscripts met eligibility criteria. Two papers reported different outcomes of the same study, only the paper that reported anxiety data was included. An additional two studies were excluded as subsample data (clinical sample only), were not reported and could not be obtained from authors. A total of five studies were included in this review.

Study characteristics

Characteristics of included studies are summarised in Table 1. Of the five included studies, four were open trials and one was a RCT, with a combined total of 127 participants. The majority of women across studies were pregnant or postpartum with their first child, married or in a relationship, educated to at least high school, and employed.

Mindfulness-based cognitive group therapy program

Goodman et al. (2014) conducted an open pilot study to evaluate a mindfulness-based cognitive therapy intervention. Twenty-four women (mean age 33.5 years; mean gestational age 15.5 weeks) with a clinical diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD; 70.8%) and/or meeting threshold criteria indicating an elevated level of anxiety symptoms were recruited via hospital screening, self- or clinician referral (e.g. obstetrician). Six of the 11 participants meeting criteria for GAD also had comorbid diagnoses (e.g. major depressive disorder; agoraphobia).

The intervention consisted of eight 2-h sessions delivered weekly to three groups of 6–12 women. This intervention was based on the principles of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, which combines mindfulness practices (e.g. body scan, meditation) and cognitive techniques to target symptoms of anxiety. The program’s content was tailored to common anxieties experienced by pregnant women (e.g. labour and delivery). Depression-related content was also included. The program included presentations, group exercises, formal meditation practices and leader-facilitated group discussions and was delivered in English by a social worker. Participants were required to complete 30–40 min of daily homework exercises (e.g. meditation). Twenty-three women completed the study, the majority attending at least six of the eight sessions. Participants demonstrated statistically and clinically significant improvements in anxiety severity according to the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer et al. 1990) with a moderate effect size (Hedge’ g of 0.75). Of the 16 participants meeting criteria for GAD at baseline, only one continued to meet diagnostic criteria at post-treatment according to the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al. 1998). Participants rated their experience with the intervention as positive and helpful.

Face-to-face cognitive behaviour group therapy programs

Two studies explored the effects of group-based CBT for women during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Lilliecreutz et al. (2010) conducted an open trial to evaluate a group CBT-based intervention for blood and injection phobia in pregnant women. Thirty pregnant women (mean age 28.5 years; gestational age 25–30 weeks) with a DSM-IV diagnosis of blood and injection phobia were recruited from an antenatal clinic in Sweden. Two control groups were used from a prevalence study conducted during the same time period. One control group consisted of 46 women with untreated blood and injection phobia while the second consisted of 70 healthy pregnant women, with both groups only receiving regular antenatal health care.

The two treatment sessions, scheduled 4 weeks apart, were delivered to groups of four to six women. Session one, delivered at 25–30 weeks’ gestation, consisted of education and intensive, prolonged exposure to injection-related material (e.g. syringes), including an injection demonstration by the midwife. The second session included discussion of the previous session and homework, before intensive exposure to injection-related exercises (i.e. injections received by participants). The program was delivered in English by a CBT therapist and midwife. All 30 women completed both sessions and pre-post evaluations. Anxiety according to the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck and Steer 1996) was significantly reduced from the first session to the second session with a large effect size (Hedges’ g of 0.92) and gains maintained at 3-month postpartum follow-up. Injection phobia was significantly reduced over the whole study period, in addition to before and after each treatment session according to the Injection Phobia Scale (Öst 1992). Scores were also reduced at 3-month postpartum follow-up compared to the first and second occasions. Participant satisfaction with the intervention was not reported.

Green et al. (2015) conducted an open pilot study to evaluate a group CBT-based intervention specifically tailored to address perinatal anxiety. Ten women (mean age 31.2 years) were recruited from a women’s clinic at a Canadian academic hospital and were either pregnant (n = 2; mean gestational age 6 months) or within 12 months postpartum (n = 8; mean infant age 4 months) with a primary diagnosis of an anxiety disorder (7/10 generalised anxiety disorder; 3/10 social anxiety disorder).

Two treatment groups were conducted with five women per group. The intervention consisted of six 2-h weekly sessions. The program was based on traditional CBT group therapy for anxiety including psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, problem solving, relaxation, behavioural experiments and assertiveness. Program content was delivered in the context of the perinatal period through the use of relevant examples and tailored psychoeducation. Depression-related content and strategies were also included (e.g. behavioural activation). The program was presented as a manual-based intervention (including worksheets for homework) with both groups conducted in English and administered by a clinical health psychologist and psychology-trained clinician from the women’s clinic. There was a significant reduction in anxiety symptoms from pre- to post-treatment according to the PSWQ (Meyer et al. 1990) with a large effect size (Hedges’ g of 1.46). Participants rated the intervention as highly satisfactory.

Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural program (fear of childbirth)

Nieminen et al. (2016a) conducted an open pilot study to evaluate an Internet-delivered intervention for nulliparous women (i.e. first pregnancy) with severe fear of childbirth. Twenty-eight women (mean age 30.5 years; mean gestational age 24 weeks) residing in Sweden and between 18 and 30 weeks pregnant were recruited via the study home page. At baseline, the majority of women (86%) reported a phobic level of fear of childbirth (according to the antenatal component of the Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire (W-DEQ), Wijma et al. 1998) and clinical levels of anxiety (71%; according to the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS), Zigmond and Snaith 1983).

The 8-week intervention consisted of eight modules, with one module presented to participants per week. The Internet-delivered intervention was based on a self-help CBT-based manual developed for the treatment of severe fear of childbirth. Each module consisted of an information track focusing on the physiology of pregnancy, labour and delivery and possible complications; a therapy track focusing on psychoeducation and cognitive and behavioural components of treatment (e.g. breathing, cognitive restructuring, in vivo exposure, and relapse prevention) and questions and homework tasks for the current week. Participants were required to complete 2–3 h of homework tasks each week, in addition to pre- and post-treatment tasks (e.g. imagining themselves in five different delivery situations and spontaneously describing these). The intervention was supported by an Internet therapist (e.g. obstetrician) who provided short, individual feedback (e.g. motivating techniques) each week, and was available for participants to contact whenever needed.

Of the total 28 participants, 15 women completed all 8 modules. Of these women, participants demonstrated large and significant reductions in fear of childbirth symptoms (Hedges’ g of 1.95) from pre-treatment to post-treatment according to the antenatal W-DEQ. At 3 months postpartum follow-up (n = 24), the level of fear (according to the postpartum component of the W-DEQ; Wijma et al. 1998) was comparable with the normal population of primiparous women at 5 weeks’ postpartum. Participants reported the intervention as positive and convenient (e.g. no need to travel to a clinic).

Combined pharmacologic-psychological program

Misri et al. (2004) conducted an RCT to investigate the addition of individual face-to-face CBT to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), paroxetine, to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression in postpartum women. Women (mean age 30 years) were recruited from clinician referrals from an outpatient program in Canada. Participants were required to meet diagnostic criteria for a depressive or anxiety disorder (according to DSM-IV criteria) within 6 months postpartum in addition to meeting clinical cut-off scores for anxiety according to the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (≥ 20 (HAM-A), Zigmond and Snaith 1983) and depression according to the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (≥ 20 (HAM-D), Zigmond and Snaith 1983) and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (≥ 12 (EPDS), Cox et al. 1987). Women were randomly allocated to receive either paroxetine or a combination of paroxetine and CBT. Of the total 35 participants, 34 met criteria for major depressive disorder with comorbid anxiety disorders (e.g. anxiety plus obsessive-compulsive disorder).

For those in the combined paroxetine and CBT group, a 1-h individual face-to-face CBT session was delivered weekly over 12 weeks. The program focused on psychoeducation about the interrelationships between thoughts, affect, behaviour, physical reactions and environment, and strategies to promote positive change in each domain. The program was delivered in English by a registered psychologist who followed a treatment manual developed specifically for women with postpartum anxiety and depression. The overall methodological quality of this study was varied with adequate random sequence generation, low risk of attrition bias (32/35 completed outcome data) and detection bias (clinician-administered outcome assessments) but high risk of performance bias (i.e. not blinded to group allocation). Statistically significant improvements in anxiety symptoms were evident in both the paroxetine and the combined CBT plus paroxetine treatment groups from baseline to post-treatment according to the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A; Hamilton 1959). There was a large within-group effect size (Hedges’ g of 1.77) for the pre- to post-change in the combined CBT plus paroxetine treatment group. The combined paroxetine and CBT group did not demonstrate any additional treatment advantages in comparison to monotherapy group (i.e. paroxetine only), with a small and nonsignificant between-group effect size (Hedges’ g of 0.06) from baseline to post-treatment. Participant satisfaction with the intervention was not reported.

Discussion

This paper presents the first review of psychological treatments for clinical anxiety during the perinatal period. Overall, there was little research evaluating the treatment of clinical anxiety in perinatal women. We identified only five studies, four uncontrolled pilot studies and one RCT with a total of 127 participants.

Three studies investigated brief group-based protocols, based on CBT or mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, delivered over six to eight sessions. One study investigated a therapist-supported, Internet-delivered CBT intervention over eight sessions to address excessive fears of childbirth, and another study evaluated a SSRI, paroxetine, in combination with face-to-face individual CBT over 12 sessions. Although we were unable to pool the interventions to examine an overall effect size, the group-based interventions individually demonstrated moderate to large and significant improvements in anxiety symptom severity from pre- to post-treatment (Hedges’ g ranged from 0.75 to 1.46). The Internet-delivered CBT intervention also demonstrated a large and significant reduction in fear of childbirth symptoms from pre- to post-treatment (Hedges’ g of 1.95). It is difficult to determine if reductions in symptoms are reflective of the effect of treatment or a natural decrease in symptoms over time, because these interventions were evaluated in uncontrolled pilot studies. However, group-based interventions appear to be acceptable and beneficial to women with clinical anxiety who were included in these studies, with high program adherence rates and patient satisfaction. Internet-delivered CBT also appears to be an acceptable form of treatment delivery for antenatal women experiencing severe to phobic levels of fear of childbirth. The combined paroxetine and CBT intervention demonstrated a large individual effect size in reducing anxiety symptom severity from pre- to post-treatment (Hedges’ g of 1.77); however, the addition of CBT demonstrated no benefits over paroxetine alone for postpartum women with moderate-to-severe anxiety (and comorbid depression).

Despite each study demonstrating positive preliminary results in reducing perinatal anxiety symptoms, the paucity of research in this area is concerning. Given maternal anxiety is associated with short- and long-term adverse outcomes for the mother and infant (e.g. increased risk of negative birth outcomes) and significant healthcare costs (Post and Antenatal Depression Association 2012; Glasheen et al. 2010), it is surprising that this area has received so little attention while considerable research has been conducted on perinatal depression. A 2011 review of treatments for perinatal depression found 19 psychological interventions and four combined psychological and pharmacological interventions (Sockol et al. 2011). Treatment for perinatal depression has also extended into the field of e-health with several computerised (i.e. Internet-delivered) interventions demonstrating significant reductions in depression symptom severity from pre- to post-treatment (e.g. Milgrom et al. 2016). We found only one study investigating an Internet-delivered treatment for women experiencing fear of childbirth during the perinatal period (Nieminen et al. 2016a). One other study has evaluated an Internet-delivered treatment for childbirth-related trauma; however, the majority of participants in this study were outside the ‘perinatal’ period (i.e. greater than 12 months since trauma; Nieminen et al.2016b). No studies have investigated the efficacy or acceptability of Internet-delivered treatment interventions for generalised anxiety symptoms (i.e. GAD) or comorbid anxiety and depression during the perinatal period. Given general anxiety symptoms and comorbid symptoms are highly prevalent in perinatal women, this is an important area of research that warrants attention.

Future RCTs are needed to evaluate the efficacy of psychological therapies for perinatal anxiety, particularly how they compare to control groups including waiting list, usual care and alternative psychological treatments, or delivery models (e.g. individual therapy, rather than group-based). In addition, it would be useful for more research to determine what treatment factors are most effective for which patients and whether the presence of anxiety disorders, or the severity of anxiety, influences response (Goodman et al. 2016). As only two studies reported outcomes at 3-month follow-up and none examined long-term follow-up, it is necessary for future research to examine long-term outcomes to determine whether the positive outcomes are sustained over a longer duration beyond the immediate completion of treatment. The majority of interventions included in our study were also developed and evaluated in English language within Western countries, with participants being well educated, married, and the majority pregnant with or having just had their first child (i.e. nulliparous). Careful interpretation of our findings is required as it is difficult to generalise our findings to perinatal anxiety interventions delivered in low-income countries or other languages.

Future studies should use clinician-administered diagnostic interviews, the current gold standard of measuring mental health problems, in addition to self-report measures of anxiety to evaluate the efficacy of treatment interventions in this population. It is important that self-report measures of anxiety, developed for use in the general population, have been validated in pregnant and postpartum women with appropriate clinical cut-offs and norms (see review; Meades and Ayers 2011). Reliance on general measures not validated in perinatal populations may limit the accurate detection of anxiety in perinatal women. For example, general measures may inflate anxiety scores on questions regarding physical symptoms of anxiety common in pregnancy (e.g. ‘I feel rested’; ‘I feel comfortable’) and may not take into account anxiety presentations that are not relevant in the general population (e.g. fear of childbirth; negative intrusive thoughts of harming the baby; Huizink et al. 2004; Somerville et al. 2014). It is also important to consider measures developed specifically for this population which take into account the psychological, social and physiological changes that accompany pregnancy and childbirth (Grant et al. 2008). For example the pregnancy anxiety scale (PAS; Levin 1991) and perinatal anxiety screening scale (PASS; Somerville et al. 2014) have been developed specifically for use in identifying anxiety in pregnant and postpartum women and the W-DEQ which has been developed to measure fear of childbirth in nulliparous women (Wijma et al. 1998). The use of psychometrically robust measures of perinatal anxiety is essential for clinical practice and research, particularly for interpreting the clinical significance of research findings and enabling researchers to compare treatment outcomes across studies.

Future intervention studies would also benefit from the evaluation of not only maternal anxiety changes but also infant- and mother-infant outcomes. Given that maternal anxiety is associated with adverse outcomes on both the mother and infant, it is important to evaluate whether changes in maternal anxiety correspond to improvements in infant- and mother-infant outcomes (e.g. mother-infant relationship; child developmental progress; Murray et al. 2003). For example, as found with depressed mothers, difficulties in the mother-infant relationship may persist even after remission of maternal symptoms (Murray et al. 2003). This information will inform how anxiety treatment interventions can be tailored most effectively to maximise the benefit to both mothers and infants (Challacombe and Salkovskis 2011).

While the small number of studies included in this review reflects the current status of the field, the review needs to be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First, the inclusion of published studies may have introduced some bias towards studies with positive findings. Second, we restricted our inclusion criteria to studies evaluating the efficacy of treatment interventions in reducing clinical levels of anxiety within the perinatal period and may therefore have excluded important studies within this field. For example, we excluded several studies evaluating preventative interventions for healthy or ‘at-risk’ women (e.g. Austin et al. 2008; Byrne et al. 2014), interventions evaluated in women with ‘elevated’ but nonclinical levels of anxiety (e.g. Bittner et al. 2014) and interventions evaluated in women outside the perinatal period (e.g. Nieminen et al. 2016b; Muzik et al. 2015).

Conclusion

This review is first to synthesise the existing literature and identify an area of research that needs urgent attention from clinicians and researchers as very few studies have evaluated psychological treatments for clinical anxiety in perinatal women. The studies included in this review demonstrate that symptoms of anxiety during the perinatal period appear to improve during treatment. However, we cannot conclude that the interventions trialled are efficacious, due to the lack of RCTs. Future research is needed to establish the efficacy of perinatal anxiety interventions in comparison to control or other active treatment conditions, whether reductions in anxiety persist long term and whether these benefits extend to other outcomes for the mother, infant and family. Given the prevalence of anxiety during pregnancy and the postpartum period and negative outcomes for both the mother and child, the identification of effective and acceptable treatments is imperative.

References

Post and Antenatal Depression Association (2012) The cost of perinatal depression in Australia. Deloitte Access Economics Pty Ltd, Canberra

Austin M-P, Frilingos M, Lumley J, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Roncolato W, Acland S et al (2008) Brief antenatal cognitive behaviour therapy group intervention for the prevention of postnatal depression and anxiety: a randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord 105(1):35–44

Austin M-P, Tully L, Parker G (2007) Examining the relationship between antenatal anxiety and postnatal depression. J Affect Disord 101(1-3):169–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.015

Ayers S, Coates R, Matthey S (2015) Identifying perinatal anxiety, First edn. Wiley, West Sussex

Beck AT, Steer RA (1996) Beck anxiety inventory. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

Betts KS, Williams GM, Najman JM, Alati R (2014) Maternal depressive, anxious, and stress symptoms during pregnancy predict internalizing problems in adolescence. Depress Anxiety 31(1):9–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22210

Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM (2016) Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 191:62–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014

Bittner A, Peukert J, Zimmermann C, Junge-Hoffmeister J, Parker LS, Stobel-Richter Y, Weidner K (2014) Early intervention in pregnant women with elevated anxiety and depressive symptoms: efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral group program. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 28(3):185–195. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0000000000000027

Byrne J, Hauck Y, Fisher C, Bayes S, Schutze R (2014) Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based childbirth education pilot study on maternal self-efficacy and fear of childbirth. J Midwifery & Women’s Health 59(2):192–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12075

Challacombe FL, Salkovskis PM (2011) Intensive cognitive-behavioural treatment for women with postnatal obsessive-compulsive disorder: a consecutive case series. Behav Res Ther 49(6):422–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.006

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 150(06):782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R (2017) Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 210(05):315–323. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187179

Fairbrother N, Janssen P, Antony MM, Tucker E, Young AH (2016) Perinatal anxiety disorder prevalence and incidence. J Affect Disord 200:148–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.082

FirstMB,GibbonM (2004) The structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II)

Glasheen C, Richardson GA, Fabio A (2010) A systematic review of the effects of postnatal maternal anxiety on children. Arch Womens Ment Health 13(1):61–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-009-0109-y

Goodman J, Guarino A, Chenausky K, Klein L, Prager J, Petersen R et al (2014) CALM pregnancy: results of a pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal anxiety. Arch Womens Ment Health 17(5):373–387

Goodman JH, Watson GR, Stubbs B (2016) Anxiety disorders in postpartum women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 203:292–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.033

Grant K-A, McMahon C, Austin M-P (2008) Maternal anxiety during the transition to parenthood: a prospective study. J Affect Disord 108(1):101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.002

Green SM, Haber E, Frey BN, McCabe RE (2015) Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for perinatal anxiety: a pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health 18(4):631–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-015-0498-z

Hamilton M (1959) The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 32(1):50–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x

Higgins J, GreenSM (2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Retrieved fromwww.handbook.cochrane.org

Hofmann SG, Smits JA (2008) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatr 69(4):621–632. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v69n0415

Huizink AC, Mulder EJ, de Medina PGR, Visser GH, Buitelaar JK (2004) Is pregnancy anxiety a distinctive syndrome? Early Hum Dev 79(2):81–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.04.014

Levin JS (1991) The factor structure of the pregnancy anxiety scale. J Health Soc Behav 32(4):368–381. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137104

Lilliecreutz C, Josefsson A, Sydsjo G (2010) An open trial with cognitive behavioral therapy for blood- and injection phobia in pregnant women—a group intervention program. Arch Womens Ment Health 13(3):259–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-009-0126-x

Meades R, Ayers S (2011) Anxiety measures validated in perinatal populations: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 133(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.009

Meyer TJ, Miller MJ, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD (1990) Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther 28(6):487–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6

MilgromJ, DanaherBG, GemmillAW, HoltC, HoltCJ, SeeleyJR, …EricksenJ (2016) Internet cognitive behavioral therapy for women with postnatal depression: a randomized controlled trial of Mum Mood Booster. J Med Internet Res 18(3)

Milgrom J, Gemmill AW (2015) Identifying perinatal depression and anxiety: evidence-based practice in screening, psychosocial assessment and management. Wiley, Hoboken. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118509722

Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Bilszta JL, Hayes B, Barnett B, Brooks J et al (2008) Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: a large prospective study. J Affect Disord 108:147–157

Misri S, Kendrick K (2007) Treatment of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders: a review. Can J Psychiatr 52(8):489–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370705200803

Misri S, Reebye P, Corral M, Milis L (2004) The use of paroxetine and cognitive-behavioral therapy in postpartum depression and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 65(9):1236–1241. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v65n0913

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Murray L, Cooper PJ, Wilson A, Romaniuk H (2003) Controlled trial of the short-and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression. Br J Psychiatry 182(5):420–427. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.182.5.420

Muzik M, Rosenblum KL, Alfafara EA, Schuster MM, Miller NM, Waddell RM, Kohler ES (2015) Mom power: preliminary outcomes of a group intervention to improve mental health and parenting among high-risk mothers. Arch Women’s Mental Health 18(3):507–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0490-z

Nieminen K, Andersson G, Wijma B, Ryding E-L, Wijma K (2016a) Treatment of nulliparous women with severe fear of childbirth via the Internet: a feasibility study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 37(2):37–43. https://doi.org/10.3109/0167482X.2016.1140143

Nieminen K, Berg I, Frankenstein K, Viita L, Larsson K, Persson U et al (2016b) Internet-provided cognitive behaviour therapy of posttraumatic stress symptoms following childbirth—a randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther 45(4):287–306

O'Hara MW, Wisner KL (2014) Perinatal mental illness: definition, description and aetiology. Best Pract Res Clin Obstret Gynaecol 28(1):3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.09.002

Öst L-G (1992) Blood and injection phobia: background and cognitive, physiological, and behavioral variables. J Abnorm Psychol 101(1):68–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.101.1.68

Ross LE, McLean LM (2006) Anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry 67(08):1285–1298. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v67n0818

Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J et al (1998) Diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59:22–33

Sockol L, Epperson CN, Barber JP (2011) A meta-analysis of treatments for perinatal depression. Clin Psychol Rev 31(5):839–849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.009

Somerville S, Dedman K, Hagan R, Oxnam E, Wettinger M, Byrne S et al (2014) The perinatal anxiety screening scale: development and preliminary validation. Arch Womens Ment Health 17(5):443–454

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene PR, Vagg PR, Jacobs AG (1970) Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M et al (2014) Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 384(9956):1800–1819

Stewart RE, Chambless DL (2009) Cognitive–behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C.

Wijma K, Wijma B, Zar M (1998) Psychometric aspects of the W-DEQ; a new questionnaire for the measurement of fear of childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 19(2):84–97. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674829809048501

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Contributors

SL, JN and GA designed the study and wrote the protocol and search strategy. SL, MW, AJ and HH conducted the searches, screened the titles, abstracts and full-texts for eligibility for inclusion. SL extracted the data from manuscripts, independently checked by MW, and conducted the data analysis with supervision from JN. All authors contributed to and have approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This study was supported by the Australian Rotary Health and the David Henning Memorial Foundation in the form of a PhD scholarship awarded to Siobhan Loughnan. Rotary Health Australia and the David Henning Memorial Foundation had no role in the study design, collection, data analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The protocol was developed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins and Green 2011), was registered with PROSPERO [CRD42017052446] and followed the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al. 2009).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

PsycINFO Search

-

1.

(Perinatal OR peripartum OR antenatal OR antepartum OR prenatal OR pregnan* OR postnatal OR postpartum OR birth OR (after birth)).mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests and measures]

-

2.

(Anxiety OR (anxiety disorder) OR worry OR distress OR stress OR (generali$ed. anxiety disorder) OR general$ anxiety OR obsessive compulsive disorder OR (post-traumatic stress disorder) OR (traumatic stress) OR agoraphobia OR phobia$ OR (health anxiety) OR depression) mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests and measures]

-

3.

(Intervention OR treatment OR therap* OR (treatment outcome) OR self-help OR counsel$ing OR psychotherapy* OR bibliotherapy OR (behave$ change) OR CBT OR (cognitive behave$ therapy) OR (cognitive therapy) OR (interpersonal psychotherapy) OR (psychodynamic therapy) OR relaxation).mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests and measures]

-

4.

1 and 2 and 3

-

5.

Limit 4 to (human, adulthood and English language)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Loughnan, S.A., Wallace, M., Joubert, A.E. et al. A systematic review of psychological treatments for clinical anxiety during the perinatal period. Arch Womens Ment Health 21, 481–490 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0812-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0812-7