Abstract

Purpose

Cancer survivors experience significant health concerns compared to the general population. Sydney Survivorship Clinic (SSC) is a multi-disciplinary clinic aiming to help survivors treated with curative intent manage side effects, and establish a healthy lifestyle. Here, we determine the health concerns of survivors post-primary treatment.

Methods

Survivors completed questionnaires assessing symptoms, quality of life (QOL), distress, diet, and exercise before attending SSC, and a satisfaction survey after. Body mass index (BMI), clinical findings and recommendations were reviewed. Descriptive statistical methods were used.

Results

Overall, 410 new patients attended SSC between September 2013 and April 2018, with 385 survivors included in analysis: median age 57 years (range 18–86); 69% female; 43% breast, 31% colorectal and 19% haematological cancers. Median time from diagnosis, 12 months. Common symptoms of at least moderate severity: fatigue (45%), insomnia (37%), pain (34%), anxiety (31%) and with 56% having > 5 moderate-severe symptoms. Overall, 45% scored distress ≥ 4/10 and 62% were rated by clinical psychologist as having ‘fear of cancer recurrence’. Compared to population mean of 50, mean global QOL T-score was 47.2, with physical and emotional well-being domains most affected. Average BMI was 28.2 kg/m2 (range 17.0–59.1); 61% overweight/obese. Only 31% met aerobic exercise guidelines. Overall, 98% ‘agreed’/‘completely agreed’ attending the SSC was worthwhile, and 99% would recommend it to others.

Conclusion

Distress, fear of cancer recurrence, fatigue, obesity and sedentary lifestyle are common in cancer survivors attending SSC and may best be addressed in a multi-disciplinary Survivorship Clinic to minimise longer-term effects. This model is well-rated by survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Improvements in screening for and treatment of cancer, together with an ageing population, have resulted in rapidly increasing numbers of survivors of adult cancers. Cancer survivors are estimated to reach more than 21.3 million in the USA alone by 2026, and this number is projected to increase rapidly [1].

Research has consistently shown adults who have survived even early-stage cancer have poorer health than the general population, with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis and risk of cancer recurrence [2, 3]. Many cancer survivors continue to suffer treatment-related side effects resulting in substantial distress, impacting quality of life (QOL), reducing their independent functional ability and decreasing productivity [4]. These issues are often multifactorial, complex and not always easily addressed by the patients’ general practitioner (GP) or during routine oncology follow-up (e.g. with a medical or radiation oncologist, or surgeon). Furthermore, there is growing evidence of lifestyle risk factors, such as physical inactivity, obesity and excessive alcohol intake, increasing the risk of a new cancer or cancer recurrence [5]. A model of care consisting of multi-disciplinary health professionals with a good understanding of the disease trajectory and experience in treating cancer patients could address these health concerns in a coordinated and timely manner, and provide information to help cancer survivors modify their lifestyle risk factors to improve clinical outcomes.

The Sydney Survivorship Centre at Concord Cancer Centre, founded in 2013, included a new initiative with a multi-disciplinary Survivorship Clinic for survivors of adult cancers who had completed primary treatment (+/− surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy) for early-stage breast or colorectal cancer treatment. In 2014, the clinic expanded to include haematological malignancies, then other solid tumour types in 2015. At the initial clinic visit, survivors consulted a medical oncologist/haematologist, cancer nurse specialist, exercise physiologist, dietitian and clinical psychologist to develop a management plan based on current evidence and guidelines. Where appropriate, patients were referred to attached survivorship programmes promoting healthy lifestyles, such as the Survivorship gym, or other health services, such as a sexual health clinic. This paper aimed to describe the patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and health status of patients attending their initial visit at the Sydney Survivorship Clinic between September 12, 2013, and April 5, 2018, and their acceptance of the MDT clinic [6].

Methods

This was a single site, longitudinal study in which patient-reported outcome data were collected as part of standard care and for quality assurance. The current analysis reports baseline characteristics of clinic attendees, self-reported health issues and clinical data from the initial clinic visit, and satisfaction rating at the end of their first clinic.

Patients eligible for the Survivorship Clinic are survivors of adult cancers who have completed potentially curative primary treatment that includes chemotherapy, with no evidence of disease recurrence. Breast cancer patients may be receiving hormonal treatment and/or targeted treatment. Referrals from patients with complex survivorship issues who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy are occasionally accepted [6].

Cancer survivors referred to the Sydney Survivorship Clinic were mailed a package of paper patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) prior to their appointment and asked to bring completed forms to clinic. These are described in full elsewhere [6] but, in brief, assessed aerobic exercise, food intake, distress [7], quality of life (QOL) [8] and symptoms [9] (outlined in Appendix Table 1). The 48 symptoms measured using the Patient’s Disease and Treatment Assessment Form-General [9] were scored from 0 to 10 (from no trouble at all to worst I can imagine) with a score of 4 or above being classified as at least moderate intensity. From 2013 to 2016, the physical activity questionnaire sent to survivors was the Active Australia questionnaire [10], replaced in 2017 with the modified Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (LTEQ) [11]. Clinic staff performed anthropometric measurements (weight, body mass index). The clinical psychologist saw each survivor for at least 20 min, and as part of their clinical interview, provided brief psychoeducation about fear of cancer recurrence (FCR), describing its common features, prevalence and quality of life impact. Patients were encouraged to identify their own symptoms, or lack thereof, and then asked to compare their experience against this description, and, when appropriate, to self-rate the severity of their FCR. The psychologist diagnosed the presence, absence and level of severity of FCR symptoms based on both the reported self-rating and/or the psychologist’s own observations about the patients’ affective state when they described their experience, as well as the reported efficacy (or otherwise) of the patients’ coping strategies and the impact of the FCR on their quality of life. Recommendations as to the benefits of further psychological follow-up were based on the outcome of this assessment. Demographic and disease information were accessed from the medical record. An individualised Survivorship Care Plan (SCP) was prepared by the oncologist, or Survivorship Nurse for haematology survivors, prior to clinic using medical records, and updated in consultation with the survivor. The SCP was a modified version of the disease-specific templates provided by the American Society of Clinical Oncology [12, 13]. The SCP contained a summary of medical information including treatment received, surveillance recommendations and personalised recommendations from the multi-disciplinary team. The SCP was mailed to survivors, their general practitioner and specialists involved in their care after being updated by the team. Survivors completed a written evaluation form at the conclusion of the clinic, which could be completed anonymously and placed in a box on the reception desk.

All data were entered into a custom designed REDCap™ database. Ethics approval was obtained from Concord Repatriation General Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/14/CRGH/23). Survivors seen prior to July 17, 2014, had consent waived allowing use of their de-identified data unless they were returning to the Survivorship Clinic for follow-up, in which case consent was required to be obtained at that time.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was pragmatically determined by the number attending the Survivorship Clinic from September 2013 until April 2018. Descriptive statistics were used to report symptoms, exercise and dietary behaviour, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) reported where appropriate. The overall mean QOL and domain scores were converted to T-scores and compared with general Australian population data [14]. The number who completed an assessment is indicated in the manuscript and tables by the denominator. IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 was used for all analyses.

Results

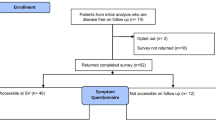

A total of 410 new survivors attended their initial Sydney Survivorship Centre Clinic from September 2013 to April 2018, with data from 385 survivors included in the main analysis (Appendix Fig. 1). In total, 240/250 (96%) of cancer patients were referred to the MDT Survivorship Clinic by other medical oncologists or haematologists working in Concord Hospital. Referral for ongoing follow-up was made for a third (103/325) of the attendees but here we report only baseline data of all attendees. Consent was waived for 62 (15%) participants. In total, 25 (6%) survivors were excluded from the analysis as they either did not consent for their data to be used or their consent forms could not be located.

The overall response rate for PROM was 80–87%, except for the FACT-G, where due to an administrative error, the rate was 72%. Missing PROM responses were mainly due to insufficient English language skills.

Patients’ characteristics and health concerns

The median age of survivors attending the clinic for the first time was 57 years (range 18–86); 69% of all attendees were women. Tumour types were breast 43%, colorectal 31%, haematological 19% and 7.5% other (mainly upper gastrointestinal) cancers. Most survivors previously had undergone surgery (81%) and chemotherapy (88%), and 44% radiation therapy. Survivors were a median of 12 months post cancer diagnosis or surgery, ranging from 1.6 to 327.8 months, including a small number of long-term haematology survivors. At the time of their initial Survivorship Clinic visit, 72% of breast cancer survivors were on adjuvant endocrine treatment, and 26% had or were currently receiving targeted therapy (see Table 1 for details).

Lifestyle risk factors—physical activity and obesity

Based on the Active Australia and Leisure Time Equivalent questionnaires, 31% of survivors met the recommended guidelines of at least 150 min/week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, or 75 min/week of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity (Table 2). Information on resistance training was available for 90 survivors. Only 3/90 (3%) survivors met the current exercise guidelines for aerobic exercise plus two resistance training sessions per week. The mean body mass index (BMI) at time of their initial Survivorship Clinic visit was 28.2 kg/m2 (range 17.0–59.1 kg/m2); 233/368 (63%) survivors were overweight or obese (Table 2).

Stress and fear of cancer recurrence

The mean score on the distress thermometer was 3.5/10 (SD 2.8, range 0–10) with 151/335 (45%) rating their distress in the past week as 4 or above, meeting guidelines for further investigation [15] (Table 3). Our clinical psychologist classified 173/281 (62%) survivors as having fear of cancer recurrence based on their initial consultation. Severity was rated in 77, with 39 (51%) rated as moderate to severe. Overall, 135/329 (41%) were recommended psychological follow-up; of these, 29 (9%) were already receiving regular psychological care.

Quality of life

QOL scores as assessed by the FACT-G [16] showed a mean global score of 81.7 (SD 16.7) with physical (22.6, SD 4.9) and emotional well-being (18.0, SD 4.4) the domains most impacted. The mean T-scores for these domains were 42.6 and 41.5, respectively, which is almost one standard deviation below that seen in an Australian general population (expected mean 50, 1 SD = 10). The mean global QOL T-score was 47.2 (Fig. 1).

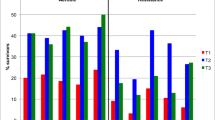

Symptoms and health concerns

Figure 2 illustrates the most common symptoms of at least moderate severity reported by cancer survivors by tumour groups. Common symptoms of at least moderate severity (rated 4+/10) were fatigue (45%), insomnia (37%), pain (34%), anxiety (31%), sore hands/feet (30%), numbness (30%) and trouble concentrating (27.5%). In total, 21.5% reported at least moderate problems with sex. Overall, 97/266 (36%) reported at least five symptoms of moderate severity or higher, with 21/44 (48%) at least 2 years post diagnosis or surgery having five or more symptoms. Approximately half of survivors self-rated their energy level as ‘fair’ to ‘worst possible’ (182/333, 55%) and one-third (116/333, 35%) rated their overall well-being as ‘fair’ to ‘worst possible’.

In total, 38/113 (34%) had more than two lifestyle risk factors (overweight, not meeting exercise guidelines), in addition to psychological issues (distress thermometer score of 4+/10, and/or rated as having fear of cancer recurrence), and five or more symptoms of at least moderate severity.

Patient feedback on the MDT survivorship model

Overall, 98% (301/307) of participants ‘agreed’ or ‘completely agreed’ attending the Survivorship Clinic was worthwhile, and 98% (233/235) said they would recommend it to others. Most thought the timing of the first clinic visit (generally being seen 3–6 months after completion of primary adjuvant treatment) was ‘right’, but 22% (52/234) said they could have benefited from attending earlier in their cancer journey. Seeing a multi-disciplinary team was reported as the main strength of the clinic.

Discussion

Follow-up of cancer survivors is important in terms of surveillance for cancer recurrence or a second malignancy. However, with improved survival, the importance of identifying, treating and preventing longer-term physical and psychological side effects of the initial cancer diagnosis and treatment have received greater recognition.

The multi-disciplinary Sydney Survivorship Clinic for survivors of adult cancers is the first of its kind in Australia. Our results highlight the considerable burden of morbidity many survivors live with, long after completing cancer treatment with curative intent, with 36% reporting at least five symptoms of moderate severity or higher and 55% reporting suboptimal energy levels. Fatigue was the most common symptom of at least moderate severity (45%), followed by sleep disturbance (37%), pain (34%) and symptoms of peripheral neuropathy (30%). Overall, 48% of breast cancer survivors were bothered by hot flushes. These results support the need for regular assessment and interventions to alleviate these symptoms. Of note, while one-third of survivors reported at least moderately severe pain, the aetiology of the pain was unclear. Many concerns described by cancer survivors were psychosocial rather than physical, with a third of patients reporting poor overall well-being. In particular, we found high rates of fear of cancer recurrence and psychological distress warranting referral for further clinical support.

A British survey of 1425 early cancer survivors reported that 30% had five or more unmet needs at completion of treatment, with 60% of survivors still having unmet needs 6 months later [17]. Self-reported fear of cancer recurrence was the most common concern, with 30% rating this as moderate or severe immediately post treatment, and 26% 6 months later, with uncertainty about the future 26% and 20% respectively. The strongest predictors for unmet needs 6 months after completion of treatment were unmet needs immediately post treatment, receiving hormonal treatment, affective symptoms, fear of cancer recurrence, a comorbid condition and experiencing a significant event. An Australian cross-sectional study of 117 women also found self-reported fear of cancer recurrence and existential issues were the most common concerns (33%) 2–10 years after a breast cancer diagnosis, failing to find any association between increased time from diagnosis and lower needs [18].

Interestingly, the incidence of fear of cancer recurrence in our cohort was more than double that reported in either of the above studies. Rather than indicating a higher rate of fear of cancer recurrence amongst our survivors, the higher incidence may be due to survivors being assessed by a clinical psychologist rather than self-report questionnaire. This suggests that fear of cancer recurrence may be more prevalent than suggested by PROM, but unfortunately no specific fear of cancer recurrence PROM was included for comparison. Following this observation, the clinical psychologist in our Survivorship Clinic began to rate severity of fear of cancer recurrence; in more recent attendees, 24/77 (31%) were rated as having moderate severity of fear of cancer recurrence, and 15/77 (19%) as severe. The literature suggests little association between those at highest risk of a cancer recurrence and those with strongest fear of recurrence [19], but we have yet to formally evaluate this in our population. However, the link between high rate of fear of cancer recurrence and psychological distress and reduced QOL in other studies [19] highlights the importance of assessing fear of cancer recurrence and offering evidence-based treatment, such as a tailored psychological intervention [20].

Our study, and a number of others, reported QOL in cancer survivors to be similar to that of the general population [18], although QOL may vary depending on time from diagnosis and treatment. Compared to QOL from a large population study in Queensland, our patient group’s mean T-scores were within 1 SD of the general population (mean 50; SD 10) [14]. It is important to note the age of our study cohort ranged from 18 to 86 years compared to the Queensland population study (n = 2727) aged 20–75 years. Physical and emotional well-being domains were the most affected, with T-scores of 42.6 and 41.5 respectively.

Despite mounting evidence that physical activity and a healthy body weight can reduce the risk of a recurrence of some common cancers [21,22,23], as well as decrease treatment-related side effects and improve function [24], population-based studies in the USA and Australia have shown up to 70% of cancer survivors do not meet recommended guidelines for physical activity, and 35% of breast cancer survivors are overweight or obese [2, 25,26,27,28,29]. Our cohort reflected these findings, reporting low compliance with guideline recommendations for aerobic and resistance exercise, and high rates of overweight and obesity. Actual compliance may be even lower, given evidence people overestimate their levels and intensity of physical activity [30]. In our study, 63% were overweight or obese. This highlights the need for healthy lifestyle programmes to facilitate cancer survivors’ incorporation of physical activity and a healthy diet into their daily life, with weight loss where required [31,32,33]. The Sydney Survivorship Centre has developed a number of programmes with accredited health professionals to assist survivors in instituting and maintaining a healthy lifestyle [6]. Longitudinal follow-up of the cohort will determine the impact of these lifestyle and behavioural interventions.

Satisfaction with the clinic was high. Participants consistently reported the greatest benefit was being seen by a multi-disciplinary team and having time to address their concerns with referral to support programmes as appropriate. These issues are often time-consuming to address, in routine follow-up cancer clinic appointments.

Strengths and limitations

There may be a selection bias with people with ongoing symptoms, or those more interested in self-management of their long-term health, more likely to be referred to, or to attend, the clinic. This is more likely to have occurred in the first couple of years when referral patterns were being established, particularly for haematology survivors. For the last 2 years, eligible oncology patients have been routinely referred to the Survivorship Clinic after completing chemotherapy. Missing data were an issue, either due to low English language literacy or survivors not completing questionnaires, despite attempts to overcome this barrier by using interpreters in the clinic, and encouraging survivors to complete questionnaires while waiting to be seen if they had not been completed in advance. This study evaluates 385 of 410 (94%) consecutive patients attending a Survivorship Clinic, with participants more generalisable to ‘real world’ cancer survivors than those in clinical trials.

Conclusion

Our results highlight that many cancer survivors experience concerning symptoms, mostly psychological, long after completion of their anti-cancer treatment. In particular, fatigue, sleep disturbance, symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, anxiety, distress and fear of cancer recurrence were common, highlighting the importance of a multi-disciplinary team to assess and address these concerns. The majority of survivors were overweight or obese and sedentary, indicating the need to address their weight and increase physical activity to reduce the risk of a new cancer or cancer recurrence. The Sydney Survivorship Clinic was rated highly by patients and has the potential to identify and address important concerns for cancer survivors.

References

Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, Stein KD, Alteri R, Jemal A (2016) Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66(4):271–289. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21349

Eakin EG, Youlden DR, Baade PD, Lawler SP, Reeves MM, Heyworth JS, Fritschi L (2006) Health status of long-term cancer survivors: results from an Australian population-based sample. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 15(10):1969–1976. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0122

Armenian SH, Xu L, Ky B, Sun C, Farol LT, Pal SK, Douglas PS, Bhatia S, Chao C (2016) Cardiovascular disease among survivors of adult-onset cancer: a community-based retrospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 34(10):1122–1130. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0409

Keating NL, Norredam M, Landrum MB, Huskamp HA, Meara E (2005) Physical and mental health status of older long-term cancer survivors. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(12):2145–2152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00507.x

World Cancer Research Foundation (2018) Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer: a global perspective. Continous update project report 2018. . https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Summary-third-expert-report.pdf. Accessed 7th Aug 2018

Vardy JL, Tan C, Turner JD, Dhillon H (2017) Health status and needs of cancer survivors attending the Sydney Survivorship Centre clinics and programmes: a protocol for longitudinal evaluation of the centre’s services. BMJ Open 7(5):e014803. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014803

Tuinman MA, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Hoekstra-Weebers JE (2008) Screening and referral for psychosocial distress in oncologic practice: use of the distress thermometer. Cancer 113(4):870–878. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23622

Cella D, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J (1993) The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11(3):10

Stockler MR, O’Connell R, Nowak AK, Goldstein D, Turner J, Wilcken NR, Wyld D, Abdi EA, Glasgow A, Beale PJ, Jefford M, Dhillon H, Heritier S, Carter C, Hickie IB, Simes RJ, Zoloft’s Effects on S, survival Time Trial G (2007) Effect of sertraline on symptoms and survival in patients with advanced cancer, but without major depression: a placebo-controlled double-blind randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 8(7):603–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70148-1

Brown WJ, Trost SG, Bauman A, Mummery K, Owen N (2004) Test-retest reliability of four physical activity measures used in population surveys. J Sci Med Sport 7(2):11

Amireault S, Godin G, Lacombe J, Sabiston CM (2015) The use of the Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire in oncology research: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 15:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-015-0045-7

McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, Reaman GH, Tyne C, Wollins DS, Hudson MM (2013) American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol 31(5):631–640. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854

Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, Merrill JK, Wollins DS, Shulman LN (2014) American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract 10(6):345–351

Janda M, DiSipio T, Hurst C, Cella D, Newman B (2009) The Queensland Cancer Risk Study: general population norms for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G). Psychooncology 18(6):606–614. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1428

Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, Fleishman SB, Zabora J, Baker F, Holland JC (2005) Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer 103(7):1494–1502. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20940

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J et al (1993) The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11(3):570–579. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570

Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, Morgan H, Murrells T, Oakley C, Palmer N, Ream E, Young A, Richardson A (2009) Patients’ supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: a prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol 27(36):6172–6179. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5151

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hobbs K, Hunt G, Lo S, Wain G (2007) Assessing unmet supportive care needs in partners of cancer survivors: the development and evaluation of the Cancer Survivors’ Partners Unmet Needs measure (CaSPUN). Psycho-Oncology 16(9):805–813

Thewes B, Husson O, Poort H, Custers JAE, Butow PN, McLachlan SA, Prins JB (2017) Fear of cancer recurrence in an era of personalized medicine. J Clin Oncol 35(29):3275–3278. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.72.8212

Butow P, Turner J, Gilchrist J, Sharpe L, Smith A, Fardell J, Tesson S, O’Connell R, Girgis A, Gebski V, Asher R, Mihalopoulos C, Bell M, Grunewald Zola K, Beith J, Thewes B, Conquer-Fear Authorship Group (2017) A randomised trial of ConquerFear: a novel, theoretically-based psychosocial intervention for fear of cancer recurrence. J Clin Oncol in press

Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, Rock CL, Demark-Wahnefried W, Bandera EV, Gapstur S, Patel AV, Andrews K, Gansler T (2012) American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin 62(1):30–67

Lemanne D, Cassileth B, Gubili J (2013) The role of physical activity in cancer prevention, treatment, recovery, and survivorship. Oncology (Williston Park) 27(6):580–585

Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, Anderson GL, Thomson CA, Manson JE, Simon MS, Howard BV, Rohan TE, Snetselar L, Lane D, Barrington W, Vitolins MZ, Womack C, Qi L, Hou L, Thomas F, Prentice RL (2017) Low-fat dietary pattern and breast cancer mortality in the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 35(25):2919–2926. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0326

Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Are M, Baker KS, Broderick G, Demark-Wahnefried W, Friedman DL, Goldman M, Jones LW, King A, Ku GH, Kvale E, Langbaum TS, McCabe MS, Melisko M, Montoya JG, Mooney K, Morgan MA, Moslehi JJ, O’Connor T, Overholser L, Paskett ED, Peppercorn J, Rodriguez MA, Ruddy KJ, Sanft T, Silverman P, Smith S, Syrjala KL, Urba SG, Wakabayashi MT, Zee P, McMillian NR, Freedman-Cass DA (2016) NCCN guidelines insights: survivorship, version 1.2016. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 14(6):715–724

Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL, Bandera EV, Hamilton KK, Grant B, McCullough M, Byers T, Gansler T (2012) Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 62(4):243–274. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21142

Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K (2008) Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol 26(13):2198–2204

Coups EJ, Ostroff JS (2005) A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Prev Med 40(6):702–711

Eakin EG, Youlden DR, Baade PD, Lawler SP, Reeves MM, Heyworth JS, Fritschi L (2007) Health behaviors of cancer survivors: data from an Australian population-based survey. Cancer Causes Control 18(8):881–894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-007-9033-5

Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, Irwin ML, Wolin KY, Segal RJ, Lucia A, Schneider CM, von Gruenigen VE, Schwartz AL, American College of Sports M (2010) American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42(7):1409–1426. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112

Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Gorber SC, Tremblay M (2008) A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 5(1):56

Hayes SC, Rye S, DiSipio T, Yates P, Bashford J, Pyke C, Saunders C, Battistutta D, Eakin E (2013) Exercise for health: a randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a pragmatic, translational exercise intervention on the quality of life, function and treatment-related side effects following breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 137(1):175–186

Courneya KS, Vardy J, Gill S, Jonker D, O’Brien P, Friedenreich CM, Dhillon H, Wong RK, Meyer RM, Crawford JJ (2014) Update on the Colon Health and Life-Long Exercise Change Trial: a phase III study of the impact of an exercise program on disease-free survival in colon cancer survivors. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep 10(3):321–328

Mishra SI, Scherer R, Geigle P, Berlanstein D, Topaloglu O, Gotay C, Snyder C (2009) Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8(1)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Erika Jungfer, Loraine Fong and Mashaal Hamayun for their assistance with data entry.

Funding

Dr. Janette Vardy is supported by a Practitioner Fellowship from the National Breast Cancer Foundation, Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, S.Y., Turner, J., Kerin-Ayres, K. et al. Health concerns of cancer survivors after primary anti-cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 27, 3739–3747 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04664-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04664-w