Abstract

Background

Sydney Cancer Survivorship Centre (SCSC) clinic provides multidisciplinary care after primary adjuvant treatment, with ~ 40% of attendees continuing follow-up with SCSC.

Methods

SCSC survivors completed measures of symptoms, quality-of-life and lifestyle factors at initial visit (T1), first follow-up (T2) and 1 year (T3). Analyses used mixed effect models, adjusted for age, sex and tumour type.

Results

Data from 206 survivors (2013–2019) were included: 51% male; median age 63 years; tumour types colorectal 68%, breast 12%, upper gastrointestinal 12%, other 8%. Mean time from: T1 to T2, 3.6 months; T1 to T3, 11.8 months. Mean weight remained stable, but 45% (35/77) of overweight/obese survivors lost weight from T1 to T3. Moderately-intense aerobic exercise increased by 63 mins/week at T2, and 68 mins/week T3. Proportion meeting aerobic exercise guidelines increased from 20 to 41%. Resistance exercise increased by 26 mins/week at T2. Global quality-of-life was unchanged from T1 to T2, improving slightly by T3 (3.7-point increase), mainly in males. Mean distress scores were stable, but at T3 the proportion scoring 4+/10 had declined from 41 to 33%. At T3, improvements were seen in pain, fatigue and energy, but > 20% reported moderate–severe fatigue, pain or sleep disturbance. Proportion reporting 5+ moderate–severe symptoms declined from 35% at T1 to 26% at T3, remaining higher in women.

Conclusions

Survivors attending SCSC increased exercise by 3 months, and sustained it at 1 year. Most overweight/obese survivors avoided further weight gain. Survivors had relatively good quality-of-life, with improvement in many symptoms and lifestyle factors at 1 year.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Article

Background

The landmark 2006 US Institute of Medicine report ‘Lost in Transition’ highlighted that the post-treatment phase for cancer patients with early stage disease is a distinct phase that requires increased attention [1]. The report emphasised poor coordination of care, under-recognition of levels of distress and failure to address psychosocial and supportive needs of many survivors and their families. In 2018, the US National Academy of Medicine Report [2] stated that current models of care still do not meet the needs of many survivors, with many remaining as ‘lost in transition’ as they were in 2006.

In 2014, it was estimated that one in 22 Australians were cancer survivors, with 5-year relative survival of 69% in Australia across all cancers for the period 2011 to 2015 [3]. With rapid increase in both the number of survivors, and duration of their survival, and many survivors having sustained or late treatment-related side effects and poorer general health [4], it is essential to focus on improving the quality of survival. There is increasing observational evidence that instituting healthy lifestyle behaviours such as exercise, a healthy diet and maintaining a healthy weight can contribute to improved cancer-specific outcomes as well as general improved health [5,6,7,8].

The Sydney Cancer Survivorship Centre (SCSC) clinic was established at Concord Cancer Centre, to provide multi-disciplinary care for survivors of adult cancers who had completed primary treatment (± surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy) for their cancer [9, 10]. The service opened in September 2013 using a staged approach, initially for survivors with early stage breast or colorectal cancer who had received chemotherapy, expanding in 2015 to include other tumour groups. Survivors are seen individually by all members of the multi-disciplinary team at their first visit (medical oncologist/haematologist, cancer nurse specialist, exercise physiologist, dietitian and clinical psychologist) and a Survivorship Care Plan (SCP) developed. The SCP is based on a modified American Society Clinical Oncology template but includes individualised recommendations from every member of the multi-disciplinary team regarding cancer care and healthy lifestyle. The focus of the survivorship clinic is to co-ordinate care, assess and treat ongoing or emergent physical and psychological symptoms, facilitate healthy lifestyle behaviours (with individualised recommendations regarding exercise, healthy diet, smoking and alcohol), prevent or minimise cancer and treatment sequelae, as well as surveillance for new primary or recurrent cancers [1]. Referrals to our SCSC or community programmes and other health care professionals are arranged, and include referral for an assessment and individualised exercise programme at our survivorship gym if appropriate. Where possible, clinical care recommendations are based on available guidelines, such as the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA) exercise guidelines for cancer survivors [11]. At the request of the referring doctor, generally the medical oncologist, ~ 40% of the survivors receive ongoing cancer follow-up in the SCSC clinic. There are differences in the local referral patterns based on tumour type, with almost all breast cancer survivors returning to their treating oncologist for ongoing follow-up, while gastrointestinal survivors continue follow-up through the survivorship clinic. Our follow-up schedule is structured so survivors are seen three monthly for years 1–3 after diagnosis, then 6-monthly years 4–5. They are routinely seen by a medical oncologist and survivorship nurse specialist.

There are limited prospective data available on novel models of survivorship care, in particular longitudinal real-world data. Here, we aimed to evaluate longitudinal changes in symptoms, quality-of-life (QOL) and lifestyle factors in survivors receiving follow-up care at the SCSC Clinic.

Methods

This is a longitudinal study evaluating cancer survivors attending the SCSC clinic at Concord Cancer Centre. This analysis evaluates longitudinal changes over the first year a survivor attended the SCSC between September 2013 and July 2019. Survivors’ data were included for analysis if they had attended at least one follow-up clinic, and provided consent for their de-identified data to be used. Assessments included were initial visit (T1), first follow-up visit (T2), and 12-month (or 1-year) visit (T3). T2 was defined as the first follow-up visit after survivors’ initial visit if it occurred within 6 months of their initial clinic. T3 was defined as the visit closest in date to 1 year after survivors’ initial clinic if the visit was between 9 and 15 months after their initial clinic.

Prior to each clinic visit, survivors are mailed a package of paper-based Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and asked to bring the completed questionnaires to their appointment. The PROMs are reviewed with patients as part of their standard visit. The PROMs completed at baseline are described in detail elsewhere [9, 10] but include exercise (Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (LTEQ) [12]), diet (3-day food diary and food questionnaire designed by team for clinical purposes), distress (Distress Thermometer [13]), QOL (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General (FACT-G) [14]) and symptoms (Patient’s Disease and Treatment Assessment Form—General [15]). On subsequent visits, the survivors were asked about dietary changes, leisure time exercise levels and alcohol intake. Survivors are weighed at each visit.

Ethics approval was obtained from Concord Repatriation General Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/14/CRGH/23). All participants’ contributing data to the analysis have provided written informed consent. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Sydney [16, 17].

Statistical analysis

Sample size was pragmatic based on the number of survivors attending the SCSC clinic for follow-up in the defined period. FACT-G scores were converted to T-scores and compared with general Australian population data that is not cancer-specific [18]. To analyse continuous PROMs (e.g., minutes of weekly exercise) separate linear mixed-effects models were estimated with PROMs acting as dependent variables. Ordered logistic mixed-effects models were estimated to analyse discrete ordinal PROMs measured on a Likert scale, including distress and symptoms, with coefficients expressed as adjusted odds ratios (AORs). To analyse longitudinal changes in PROMs, T1 was compared with T2 and T3, which were included in the models as the main covariates of interest. The choice of visits was pragmatic, allowing longitudinal changes to be illustrated without overly comprising sample size. Covariates to control for age, gender and cancer type were also included in the models. Descriptive statistics were calculated to further analyse changes in variables of interest. Stata 13 [19] was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

During the period September 2013 to July 2019, 609 new patients attended the survivorship clinic; excluding the 104 haematology patients who all only attend an initial visit, 41% of medical oncology patients had ongoing follow-up with the survivorship clinic. Data for 206 survivors who attended an initial SCSC clinic and at least one follow-up clinic in this timeframe were included in the analysis. The median time from diagnosis to first SCSC visit (T1) was 11 months. T2 occurred a mean of 3.6 months after T1 (SD 0.9; N = 154), and T3 a mean of 11.7 months after T1 (SD 1.4; N = 122).

The response rates for PROMs at T1 were approximately 90% for distress, symptoms and exercise variables and 80% for FACT-G. Denominators are shown in each table to indicate number completed. There was no difference in compliance with PROMs by tumour types. Main reasons for missing data were lack of English fluency and not receiving PROMs prior to clinic.

Patient characteristics

The median age of survivors at T1 was 63 years (range 32–91); 51% were male. The most common tumour type was colorectal (68%), others included breast (12%), upper GI (12%), lung (6%) and others (2%). Survivors’ prior treatments included surgery (99%), chemotherapy (83%) and radiotherapy (21%) (Table 1).

Changes in exercise and weight

Compared with T1, there was a statistically significant increase in self-reported weekly moderate-intensity aerobic exercise by 63 min at T2 (p < 0.01) and 68 min at T3 (p < 0.01). A significant increase was also seen in weekly vigorous aerobic exercise of 32 min at T3 (p = 0.04) (Table 2). The proportion of survivors meeting aerobic exercise guidelines of at least 150 min per week of moderate aerobic exercise or 75 min of vigorous aerobic exercise increased from 20% at T1 to 41% at T2 and T3 (Fig. 1). This increase held for both females and males, as well as for patients classified as overweight or obese.

Survivors reported increasing their weekly resistance exercise by 26 min (p < 0.01) at T2 and 25 min at T3 (p < 0.01). The proportion of survivors meeting recommended guidelines of ≥ 2 sessions per week of resistance exercise increased from 9% at T1 to 33% at T2, before declining to 18% at T3 (Fig. 1). The decline in resistance exercise at T3 was driven by survivors classified as overweight or obese; while patients with a BMI of 25 or below increased resistance exercise slightly between T2 and T3.

Overall, there was a small increase in mean body weight of 1.0 kg at T3 compared with T1 (p < 0.01). The proportion of survivors classified as overweight or obese based on Body Mass Index (BMI) 25 kg/m2 and above changed little: 64% at T1, 61% at T2 and 68% at T3. Of the survivors rated as overweight or obese at T1, 35/77 (45%) had lost weight by T3 with 19% losing more than 2 kg, and 9% more than 5 kg by T3 (Table 2).

Of these, male survivors had higher rates of weight loss with 49% losing weight, 23% losing more than 2 kg and 9% losing more than 5 kg by T3, whereas for female survivors 41% lost weight, 15% lost more than 2 kg and 9% lost more than 5 kg. Rates were almost the same for weight loss when restricted to only overweight or obese CRC and breast cancer survivors; with 44% losing weight by T3, 17% more than 2 kg and 8% more than 5 kg.

Of those overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25), 9% lost more than 5% of bodyweight between T1 and T3 (considered to be of clinical significance) [20], with no difference between males and females, compared with 3% for survivors with a BMI < 25.

Quality-of-life

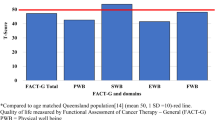

There was no statistically significant difference in survivors’ global QOL score as assessed by the FACT-G between T1 and T2, but a small improvement at T3 (3.7-point increase in mean FACT-G T-score relative to T1; p < 0.01). In total, 20/59 (34%) survivors increased their overall FACT-G score by more than 10% between T1 and T3. The mean FACT-G T-score of survivors at T3 was 51.2, higher than the general (not cancer-specific) Australian population mean of 50 [18]. The increase was across all four domains, with the largest increases in physical (T-score 43.8–47.2) and functional (49.2–51.7) domains (Fig. 2). However, female survivors reported no improvement in overall QOL between T1 and T3 (47.6–47.5), whereas male survivors reported a substantial increase and higher overall QOL (49.7–53.6).

Change in mean T-Scores for overall Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G) and subdomains, compared with the general Australian population. Mean Australian population T-score is 50 (SD 10) for overall FACT-G and subdomains [18]

Distress and symptoms

There were no significant changes in the mean distress thermometer scores at T2 and T3, relative to T1. However, the proportion of survivors reporting distress over the past week as 4 or above, the cut off suggesting further screening is indicated, [21] improved from 41% at T1 to 33% at T3.

Similar to QOL findings, survivors generally reported no statistically significant reduction in symptom severity between T1 and T2, the exception being a decline in severity of ‘sore hands and feet’ (AOR = 0.43, p < 0.01). In contrast, at T3 there were statistically significant reductions in the severity of several symptoms, including pain (AOR = 0.32, p < 0.01), fatigue (AOR = 0.58, p = 0.05) and trouble concentrating (AOR = 0.50, p = 0.03), as well as an improvement in energy (AOR = 2.1, p < 0.01). For many symptoms, the proportion of survivors’ reporting symptoms of at least moderate severity (rated as ≥ 4/10) reduced, although at T3, approximately a third were experiencing ongoing moderate to severe trouble with fatigue, sleep, anxiety and around 20% with pain and memory impairment (Fig. 3). There were no statistically significant reductions in symptoms of anxiety or depression. Despite this, the proportion of survivors reporting ≥ 5 symptoms of at least moderate severity declined from 38% at T1 to 26% at T3. The proportion of female survivors reporting ≥ 5 moderate to severe symptoms declined from 49 to 41%, but remained substantially higher than in men, which declined from 27 to 16%.

Common symptoms of at least moderate severity. Moderate severity is defined as survey response of 4/10 or above on the Patient’s Disease and Treatment Assessment Form-General [15]

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that many cancer survivors continue to experience a high-symptom burden after a year of follow-up in the SCSC clinic (approximately 2 years after diagnosis), with women reporting greater symptom burden and less improvements in QOL and exercise levels than men. Symptoms most commonly improving over time included fatigue, sore hands, pain and trouble concentrating, but a quarter of survivors scored ≥ 5 symptoms of at least moderate severity at 1 year, particularly fatigue, sleep disturbance, pain and memory impairment. QOL scores did not change greatly over the 1-year period, with global QOL scores similar to that of the general Australian population [18]. Two thirds of survivors remain overweight or obese, although 45% of these managed to reduce their weight. There were significant increases in survivors’ levels of aerobic and resistance exercise after attendance at the SCSC clinic.

The recently published consensus statement from the 2018 international multidisciplinary roundtable for exercise in cancer confirms exercise is generally safe for cancer survivors and “inactivity” should be avoided [8]. The consensus statement reports strong levels of evidence for exercise improving many cancer-related outcomes, including fatigue, anxiety/depression, physical functioning and health-related QOL, with moderate evidence for improving bone health and sleep. Importantly, a major step forward is that it provides evidence-based exercise prescriptions for many cancer-related outcomes. Exercise programmes are recommended to be tailored to meet an individual’s needs, but in general, aerobic exercise of moderate intensity three times/week for 12 weeks, and/or combined with twice weekly resistance training, was sufficient to see improvement in the above symptoms. Supporting the importance of increasing exercise in survivors, large observational studies and meta-analyses have shown improved survival, both all-cause and cancer-specific mortality, with higher levels of exercise [22].

Despite the benefits for exercise being known, it is estimated that only 30–40% of people with cancer meet the recommended amount of 150 min/week of moderate intensity exercise or 75 mins/week of vigorous intensity exercise, with even less (10–20%) achieving two sessions/week of resistance exercise [11, 23,24,25]. Although the majority of our patients did not meet aerobic or resistance exercise recommendations, we have shown they were able to increase their exercise levels significantly, with a doubling from baseline in the proportion meeting aerobic and resistance guidelines, up to 41% at T3 for aerobic exercise (approximately 2 years post-diagnosis), and resistance guidelines at 18%, although resistance exercise declined from a peak of 33% at T2 suggesting maintenance of resistance exercise requires a more structured approach to training. A large US prospective study comparing lifestyle factors in > 10,000 cancer survivors (all stages) to ~ 82,000 non-cancer participants found survivors participated in significantly less exercise, regardless of their baseline practices [26].

Many survivors remain overweight or obese at 1-year follow up [27]. Our results are similar to other studies demonstrating more than half of breast cancer survivors were overweight or obese [28, 29]. However, as the proportion of survivors with no further weight gain was high, it is likely attending the SCSC clinic increased awareness of the importance of healthy lifestyle behaviours. Vagenas and colleagues found breast cancer survivors in Australia had gained more weight after surgery than aged-matched control in a similar time frame [28]. Many cancer survivor guidelines include maintenance of a healthy weight as a key recommendation for cancer prevention [30, 31]. It has also been increasingly recommended that a multidisciplinary team approach is optimal in addressing weight issues.

Although our analysis did not examine the reasons our cohort were able to increase their exercise and better manage their weight, it is likely the consultation with the exercise physiologist and dietitian at the initial visit, and subsequent referrals and availability of Survivorship gym programmes contributed to these changes. Supporting this, the interim analysis from the CHALLENGE study showed that colon cancer patients who received individualised exercise plans and supervised exercise and behavioural sessions increased their exercise over a 12-month period compared with control patients who were only given written materials about increasing exercise and good nutrition [32].

Of interest, men generally improved more in exercise, symptoms, overall QOL and weight loss than women. There is a lack of research evaluating sex differences in exercise and weight management in cancer survivors, with most studies limited to single sex tumour types (e.g. breast cancer). Comparison across tumour types is complex due to treatment differences. The ongoing CHALLENGE study will provide interesting results regarding sex differences for exercise as it is a large randomised controlled trial (planned n = 962) and restricted to colon cancer survivors who have all received adjuvant chemotherapy.

In our study, men and women were equally divided, but only 12% of survivors were breast cancer survivors, and nearly all had received a taxane-containing chemotherapy regimen, which has been found to cause greater and more persistent symptom burden [33].

Comparison of symptoms and QOL with other studies is complex due to differences in patient populations (particularly tumour and treatments), PROMs, scoring systems and timing of assessments, but research in Australian and Asian cancer survivors 5 years after adjuvant treatment found the symptoms most commonly reported to be slightly higher than ours with fatigue (67%), loss of strength (62%), pain (62%), sleep disturbance (60%) and weight changes (58%) [34]. Similar to our findings, QOL was generally good, particularly in the Australian participants. Another cross-sectional Australian study evaluated QOL and symptoms in survivors of breast, colorectal and prostate cancer, melanoma and lymphoma at various stages of disease, one, three and 5 years after diagnosis, and reported similar rates of symptoms, highest in breast cancer survivors, particularly pain, anxiety or depression [35]. In the colorectal cancer survivors, which is closest to our survivorship population, sleep disturbance was reported by 38–41% from 1 to 5 years, fatigue was 38% at 1 year fluctuating between 29% at 3-years and 39% at 5, and trouble concentrating was 25 to 28%. Using longitudinal data, our study was able to show that although these symptoms remained problematic for many, there had been significant reduction in their severity approximately 2 years after diagnosis (T3), but no improvement in symptoms of anxiety or depression. A systematic review found higher prevalence of anxiety in particular, but also depression, in cancer survivors at least 2-years after diagnosis compared with healthy controls but no difference in prevalence between survivors and their spouses [36]. Interestingly, the mean score on the distress thermometer was unchanged, despite the number of people reporting a score of 4/10 or above declining.

Research comparing sex differences in a single tumour site (colo/rectal cancer) has reported mixed results: one showing no differences in QOL and symptom burden [37] whereas another better global QOL and fewer symptoms in men post treatment [38]. Another study found significant main effects for sex and colorectal cancer when compared with the general population for most QOL domains, but a significant interaction effect only for diarrhoea, suggesting disease-specific factors are important.

Taken together, our results suggest we may need to focus more on mental health to reduce anxiety and depression. Further attention may also be required for those with multiple moderate to severe symptoms early on, particularly female survivors who showed less improvement than males over time.

The improvement seen in QOL scores from T1 to T3 was of statistical significance but less than the minimal important difference previously described [39] and so may not be of clinical significance. Overall, QOL was however not dissimilar to that seen in the general Australian population [18].

Limitations include this is a single site study, and there may be a selection bias with participants restricted to those attending SCSC for ongoing follow-up. Much of the data collected are based on patient self-report, and improvement in behaviour may occur simply by being studied. Although approximately 85% of eligible survivors attend SCSC for an initial visit, the local referral pattern for ongoing follow-up is skewed to survivors of colorectal and upper gastro-intestinal cancers, with most breast cancer survivors remaining under their initial oncology teams. In view of our own baseline data [40] showing higher symptom burden in breast cancer survivors, our results cannot necessarily be extrapolated to all tumour types. Data were not paired at all three time points; rather modelling results were based on separate matched samples between T1 and T2 and T1 and T3. Missing data were an issue, particularly in those less fluent in English, who are known to have poorer outcomes [41] and are less able to participate in organised programmes due to English language difficulties, and our lack of resources to support programmes in other languages. It is particularly pertinent to the exercise PROM; participants had difficulty with the original measure used which limits the data collected particularly at T3.

A major strength of our study is the longitudinal prospective collection of comprehensive PRO data, including lifestyle variables, of ‘real-world’ survivors outside of clinical trials, with a moderate response rate for completing the patient-reported outcomes in those attending follow-up clinic.

Conclusions

Our real-world results indicate survivors attending an initial multidisciplinary survivorship clinic, with appropriate referrals to exercise facilities, are able to increase their exercise and sustain that increase, and almost half of those overweight or obese at baseline able to avoid gaining weight. Although unable to demonstrate a causal relationship between the clinic and improvement in healthy lifestyle behaviours, our results differ from the literature where survivors are more likely to gain weight and remain sedentary. While there was improvement in some common symptoms over time, anxiety and depression remained unchanged, with fatigue, sleep disturbance and pain remaining troubling. Cancer survivors, particularly women, continue to have high symptom burden 2 years after diagnosis.

References

Hewitt ME, Ganz PA, Institute of Medicine (US), American Society of Clinical Oncology (US) (2006) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition : an American Society of Clinical Oncology and Institute of Medicine Symposium. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Kline RM, Arora NK, Bradley CJ, Brauer ER, Graves DL, Lunsford NB, McCabe MS, Nasso SF, Nekhlyudov L, Rowland JH et al (2018) Long-term survivorship care after cancer treatment - summary of a 2017 National Cancer Policy Forum Workshop. J Natl Cancer Inst 110(12):1300–1310

Welfare AIoH (2019) Cancer data in Australia. In. Canberra, AIHW

Eakin EG, Youlden DR, Baade PD, Lawler SP, Reeves MM, Heyworth JS, Fritschi L (2006) Health status of long-term cancer survivors: results from an Australian population-based sample. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 15(10):1969–1976

(2004) Cancer survivorship--United States, 1971–2001, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 53(24):526–529

Brown JC, Meyerhardt JA (2016) Obesity and energy balance in GI Cancer. J Clin Oncol 34(35):4217–4224

Demark-Wahnefried W, Schmitz KH, Alfano CM, Bail JR, Goodwin PJ, Thomson CA, Bradley DW, Courneya KS, Befort CA, Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Dietz WH, Stolley MR, Irwin ML, Bamman MM, Apovian CM, Pinto BM, Wolin KY, Ballard RM, Dannenberg AJ, Eakin EG, Longjohn MM, Raffa SD, Adams-Campbell LL, Buzaglo JS, Nass SJ, Massetti GM, Balogh EP, Kraft ES, Parekh AK, Sanghavi DM, Morris GS, Basen-Engquist K (2018) Weight management and physical activity throughout the cancer care continuum. CA Cancer J Clin 68(1):64–89

Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, May AM, Schwartz AL, Courneya KS, Zucker DS, Matthews CE, Ligibel JA, Gerber LH et al (2019) Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc 51(11):2375–2390

Vardy JL, Tan C, Turner JD, Dhillon H (2017) Health status and needs of cancer survivors attending the Sydney Survivorship Centre clinics and programmes: a protocol for longitudinal evaluation of the centre's services. BMJ Open 7(5):e014803

Tan SY, Turner J, Kerin-Ayres K, Butler S, Deguchi C, Khatri S, Mo C, Warby A, Cunningham I, Malalasekera A, Dhillon HM, Vardy JL (2019) Health concerns of cancer survivors after primary anti-cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 27(10):3739–3747

Cormie P, Atkinson M, Bucci L, Cust A, Eakin E, Hayes S, McCarthy S, Murnane A, Patchell S, Adams D (2018) Clinical Oncology Society of Australia position statement on exercise in cancer care. Med J Aust 209(4):184–187

Amireault S, Godin G, Lacombe J, Sabiston CM (2015) The use of the Godin-Shephard leisure-time physical activity questionnaire in oncology research: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 15:60

Tuinman MA, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Hoekstra-Weebers JE (2008) Screening and referral for psychosocial distress in oncologic practice: use of the distress thermometer. Cancer 113(4):870–878

Cella D, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J (1993) The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11(3):10

Stockler MR, O'Connell R, Nowak AK, Goldstein D, Turner J, Wilcken NR, Wyld D, Abdi EA, Glasgow A, Beale PJ, Jefford M, Dhillon H, Heritier S, Carter C, Hickie IB, Simes RJ, Zoloft’s Effects on Symptoms and survival Time Trial Group (2007) Effect of sertraline on symptoms and survival in patients with advanced cancer, but without major depression: a placebo-controlled double-blind randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 8(7):603–612

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J et al (2019) The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 95:103208

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42(2):377–381

Janda M, DiSipio T, Hurst C, Cella D, Newman B (2009) The Queensland Cancer risk study: general population norms for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G). Psychooncology 18(6):606–614

StataCorp.: Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. In., Release 13 edn. College Station, Texas: StataCorp LP; 2013

Williamson DA, Bray GA, Ryan DH (2015) Is 5% weight loss a satisfactory criterion to define clinically significant weight loss? Obesity (Silver Spring) 23(12):2319–2320

Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, Fleishman SB, Zabora J, Baker F, Holland JC (2005) Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer 103(7):1494–1502

Patel AV, Friedenreich CM, Moore SC, Hayes SC, Silver JK, Campbell KL, Winters-Stone K, Gerber LH, George SM, Fulton JE et al (2019) American College of Sports Medicine roundtable report on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and cancer prevention and control. Med Sci Sports Exerc 51(11):2391–2402

Eakin EG, Youlden DR, Baade PD, Lawler SP, Reeves MM, Heyworth JS, Fritschi L (2007) Health behaviors of cancer survivors: data from an Australian population-based survey. Cancer Causes Control 18(8):881–894

Short CE, James EL, Girgis A, D'Souza MI, Plotnikoff RC (2015) Main outcomes of the Move More for Life Trial: a randomised controlled trial examining the effects of tailored-print and targeted-print materials for promoting physical activity among post-treatment breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 24(7):771–778

Galvao DA, Newton RU, Gardiner RA, Girgis A, Lepore SJ, Stiller A, Occhipinti S, Chambers SK (2015) Compliance to exercise-oncology guidelines in prostate cancer survivors and associations with psychological distress, unmet supportive care needs, and quality of life. Psychooncology 24(10):1241–1249

Hawkins ML, Buys SS, Gren LH, Simonsen SE, Kirchhoff AC, Hashibe M (2017) Do cancer survivors develop healthier lifestyle behaviors than the cancer-free population in the PLCO study? J Cancer Surviv 11(2):233–245

Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL, Bandera EV, Hamilton KK, Grant B, McCullough M et al (2012) Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 62(4):243–274

Vagenas D, DiSipio T, Battistutta D, Demark-Wahnefried W, Rye S, Bashford J, Pyke C, Saunders C, Hayes SC (2015) Weight and weight change following breast cancer: evidence from a prospective, population-based, breast cancer cohort study. BMC Cancer 15:28

Vance V, Mourtzakis M, McCargar L, Hanning R (2011) Weight gain in breast cancer survivors: prevalence, pattern and health consequences. Obes Rev 12(4):282–294

Ligibel JA, Alfano CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Burger RA, Chlebowski RT, Fabian CJ, Gucalp A, Hershman DL, Hudson MM, Jones LW, Kakarala M, Ness KK, Merrill JK, Wollins DS, Hudis CA (2014) American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement on obesity and cancer. J Clin Oncol 32(31):3568–3574

World Cancer Research Fund (2019) Be a healthy weight. Accessed 19 November 2019

Courneya KS, Vardy JL, O'Callaghan CJ, Friedenreich CM, Campbell KL, Prapavessis H, Crawford JJ, O’Brien P, Dhillon HM, Jonker DJ, Chua NS, Lupichuk S, Sanatani MS, Gill S, Meyer RM, Begbie S, Bonaventura T, Burge ME, Turner J, Tu D, Booth CM (2016) Effects of a structured exercise program on physical activity and fitness in colon cancer survivors: one year feasibility results from the CHALLENGE trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 25(6):969–977

Haidinger R, Bauerfeind I (2019) Long-term side effects of adjuvant therapy in primary breast cancer patients: results of a web-based survey. Breast Care (Basel) 14(2):111–116

Molassiotis A, Yates P, Li Q, So WKW, Pongthavornkamol K, Pittayapan P, Komatsu H, Thandar M, Yi M, Titus Chacko S et al (2018) Mapping unmet supportive care needs, quality-of-life perceptions and current symptoms in cancer survivors across the Asia-Pacific region: results from the international STEP study. Ann Oncol

Jefford M, Ward AC, Lisy K, Lacey K, Emery JD, Glaser AW, Cross H, Krishnasamy M, McLachlan SA, Bishop J (2017) Patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivors: a population-wide cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer 25(10):3171–3179

Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, Paul J, Symonds P (2013) Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 14(8):721–732

Arndt V, Merx H, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H (2004) Quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer 1 year after diagnosis compared with the general population: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 22(23):4829–4836

Schmidt CE, Bestmann B, Kuchler T, Longo WE, Rohde V, Kremer B (2005) Gender differences in quality of life of patients with rectal cancer. A five-year prospective study. World J Surg 29(12):1630–1641

King MT, Stockler MR, Cella DF, Osoba D, Eton DT, Thompson J, Eisenstein AR (2010) Meta-analysis provides evidence-based effect sizes for a cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire, the FACT-G. J Clin Epidemiol 63(3):270–281

Tan SY, Turner J, Kerin-Ayres K, Butler S, Deguchi C, Khatri S, Mo C, Warby A, Cunningham I, Malalasekera A, Dhillon HM, Vardy JL (2019) Health concerns of cancer survivors after primary anti-cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 27:3739–3747

Butow PN, Aldridge L, Bell ML, Sze M, Eisenbruch M, Jefford M, Schofield P, Girgis A, King M, Duggal-Beri P, McGrane J, Goldstein D (2013) Inferior health-related quality of life and psychological well-being in immigrant cancer survivors: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer 49(8):1948–1956

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anne Warby for her assistance with creating the database and Erika Jungfer, Anne Warby and Loraine Fong for their assistance with data entry.

Funding

Dr. Janette Vardy was supported by a Practitioner Fellowship from the National Breast Cancer Foundation, Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vardy, J.L., Liew, A., Turner, J. et al. What happens to cancer survivors attending a structured cancer survivorship clinic? Symptoms, quality of life and lifestyle changes over the first year at the Sydney Cancer Survivorship Centre clinic. Support Care Cancer 29, 1337–1345 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05614-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05614-7