Abstract

Goals of work

Increasing economical and administrative constraints and changes in health-care systems constitute a risk for burnout, especially for cancer physicians. However, little is known about differences across medical specialties and the importance of work characteristics.

Methods

A postal questionnaire addressing burnout, psychiatric morbidity, sociodemographics and work characteristics was administered to 180 cancer physicians, 184 paediatricians and 197 general practitioners in Switzerland.

Results

A total of 371 (66%) physicians participated in the survey. Overall, one third of the respondents expressed signs indicative of psychiatric morbidity and of burnout, including high levels of emotional exhaustion (33%) and depersonalisation/cynicism (28%) and a reduced feeling of personal accomplishment (20%). Workload (>50 h/week), lack of continuing education (<6 h/month) and working in a public institution were significantly associated with an increased risk of burnout. After adjustment for these characteristics, general practitioners had a higher risk for emotional exhaustion (OR: 2.0, 95% CI: 1.1 to 3.6) and depersonalisation (OR: 2.7, 95% CI: 1.4 to 5.3).

Conclusion

In this Swiss sample, cancer clinicians had a significant lower risk of burnout, despite a more important workload. Among possible explanations, involvement in research and teaching activities and access to continuing education may have protected them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Numerous investigations have attempted to document the impact of work activities on the mental health of cancer specialists [14, 15, 23, 29, 31, 33]. Work stress, if prolonged and intensified, can result in chronic reactions and lead professionals to negative affective states. Although still without agreed-upon definition, burnout is often used to qualify this reaction [25, 34]. Burnout has obvious clinical implications since it can precipitate professionals’ anxiety and depressive disorders or contribute to self-depreciation [19]. Three main traits are usually evaluated to detect burnout: (a) emotional exhaustion, reflecting depletion of energy and triggering emotional and cognitive distance from work, (b) depersonalisation or cynicism, which refers to impersonal thoughts and attitudes towards patients, and (c) a reduced sense of personal accomplishment or self-efficacy [18]. Latest studies have shown that over 25% of cancer clinicians report abnormal scores for emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation on the Maslach Burnout Inventory, with a prevalence approaching even 50% [14, 15, 23]. In a recent longitudinal survey, emotional exhaustion of UK medical oncologists significantly increased from 39% to 52% between 1994–2002 [27].

Research has also been conducted to identify occupational determinants that may influence the emotional behaviour of cancer specialists. Because of the demanding expectations of cancer patients, early studies focused on trying to uncover stressors linked specifically to the oncology activity, [6, 13, 15, 33]. However, structural factors representative of medical activity such as workload, either quantitative (e.g. workload for number of hours per week) or qualitative (e.g. ambiguity of demands), have appeared more consistently to be associated with doctors’ indices of stress [12, 19, 22, 24, 25, 28].

No such study has been yet conducted in Switzerland, a country that has been subject to numerous reforms of the health-care system [3, 5] in the last decade, which are known to threaten doctor’s mental health. The objective of our study was to establish first a standardised and current measure of psychiatric morbidity and burnout of Swiss cancer clinicians. Second, we wanted to compare these results with other specialists, namely paediatricians and general practitioners, taking into account the possible effects of work characteristics’ differences across these three specialties.

Materials and methods

Participants

We included all physicians working in oncology from the French-speaking part of Switzerland (N = 180) and an equivalent number of paediatricians (N = 184) and general practitioners (N = 197), selected from the registry of their respective medical associations. The sub-group of paediatricians and primary care physicians was matched for sex according to the oncology sample (women: 40%). All physicians had been working for at least 5 years or more in their specialty.

Assessment tools

The short form of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) was used to assess psychological morbidity [2, 11]. This tool developed for the general population and individuals consulting in non-psychiatric care units evaluates subjective psychological tension in the past weeks and has been widely used in studies on burnout assessment [14, 23]. Respondents are asked to rate the intensity of various psychological symptoms (12 items on e.g. anhedonia, anxiety, self-esteem) on a four point scale (“better than usual” = 0, “as usual” = 0, “less than usual” = 1 and “much less than usual” = 1). The maximal score is 12 points. A score greater or equal to 4 is indicative of psychiatric morbidity [20, 22].

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) questionnaire was used to measure symptoms of burnout [7, 19]. This instrument has been validated among various health professional groups and measures three dimensions empirically defined. Emotional exhaustion (ten items; e.g. “I feel emotionally drained from my work”) corresponds to feelings of being nervously exhausted by work. Depersonalisation (five items; e.g. “I’ve become more callous towards people since I took this job”) assesses cynical attitudes towards patients that can diminish empathy. Personal accomplishment reflects professional competence (seven items; e.g. “I feel I’m positively influencing people’s lives through my work”), a sign of increasing self-esteem and feeling of self-efficacy [30]. The questionnaire is composed of 22 propositions on feelings and attitudes towards work, each of which is part of one of the three distinct dimensions and is measured on a seven-point frequency scale from “never” to “every day”. Summing items, for each subscale separately, provides the score for every dimension. For both subscales “emotional exhaustion” and “depersonalisation”, the higher the scores, the closer the subject is from burnout syndrome, whereas it is the contrary for scores on the “personal accomplishment” subscale. Based on initial work of Maslach et al. [19], high emotional exhaustion is defined as a score ≥27, high depersonalisation as a score ≥10 and low personal accomplishment as a score ≤33. These cut-offs scores were defined as tertile of a normative health-care workers sample (N = 1104), with one third of the sample satisfying the criterion of burnout for each score.

Personal and job characteristics

Socio-demographic (e.g. sex, living alone) and work characteristics (e.g. number of years working as specialist or in the same work place, type of practice, workload, access to continuing medical education) were collected. The amount of personal information was limited (e.g. age and year of graduation from medical school were not asked) in order to preserve respondents’ anonymity.

Procedure

The questionnaire was been sent by mail to the eligible physicians, with up to two reminders (the first reminder 2 months after the initial mail and the second, 1 month after the first reminder).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, including cross-tabulation, χ 2 test, analysis of variance and non-parametric tests, were used to study the socio-demographic and work characteristics across medical specialties (oncologists, paediatricians, general practitioners). Descriptive statistics were calculated for the psychological morbidity score and burnout subscales (mean, standard deviation, quartiles) for each group of doctors. Respondents were also categorised for each score according to cut-offs of the original works. Analysis of variance and χ 2 test were used to test differences across medical specialties, where appropriate. To study the relationship between burnout and work characteristics, we dichotomised the respondents as having high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalisation or low personal accomplishment. Finally, to adjust the risk of burnout for differences in socio-demographic and work characteristics across the different medical specialties, multivariate logistic models were used. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Participation rates

Six months after the first questionnaires were sent (N = 561 but nine were not eligible because of retirement or changing address), 63% of the participants of the oncology group, 64% of the paediatricians and 72% of the general practitioners had answered.

Respondents’ characteristics

Two thirds of participants were men and most (87%) were living with someone (Tables 1 and 2). A majority of the physicians (65%) had been working in their specialty for more than 11 years. When compared to paediatricians and general practitioners, cancer physicians reported more teaching and research activities, worked more hours per week and spent more time with medical colleagues and for continuing medical education, but had less frequently a private practice and had been in the same work place for fewer years.

Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and burnout

The mean score for psychiatric morbidity was 2.7 (SD: 3.3, quartiles: 0–1–4; Table 3). According to GHQ-12 cut-off, 32% (N = 117/371) of the participating physicians had signs of psychiatric morbidity. No significant difference was found across the three specialties.

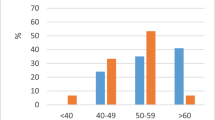

For burnout, one third (33%, N = 123/369) of physicians had high scores for emotional exhaustion (mean: 21.8, SD: 11.7, quartiles: 12–21–31), 28% (N = 102/370) for depersonalisation (mean: 6.6, SD: 5.7, quartiles: 2–5–10), and 20% (N = 72/368) expressed features of low personal accomplishment (mean: 38.6, SD: 7.1, quartiles: 35–40–44). Of note, 6% experienced high scores on both the emotional exhaustion and the depersonalisation scales and low scores on the personal accomplishment scale, reflecting a high degree of burnout. When compared to the other specialists, general practitioners displayed a higher level of depersonalisation.

Impact of job characteristics on burnout scores across medical specialties

Several work characteristics were found to have a significant influence on the three burnout components (Table 4). Working over 50 h/week was associated with an increased risk of high emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation. Spending 6 h or less per month of continuing education was also associated with a higher risk of depersonalisation. Finally, respondents working in a public institution had a higher risk to report lower personal accomplishment.

Because these work characteristics were unevenly distributed across medical specialties, we used logistic regression models to adjust our results for significant confounding factors. The risk for high emotional exhaustion, adjusted for total work time was statistically higher for general practitioners (OR: 2.0, 95% CI = 1.1 to 3.6). The risk for high depersonalisation, adjusted for total work time and hours of continuing education, was also statistically higher for general practitioners (OR: 2.7, 95% CI 1.4 to 5.3). Finally, after adjustment for the type of practice, the risk for low personal accomplishment did not vary across the three medical specialties.

Discussion

Our survey indicates that almost one third of Swiss cancer clinicians express features of emotional exhaustion, generally considered to be an early sign of burnout. Although fairly high, this prevalence of emotional exhaustion is lower than that in previous studies performed among British and Canadian cancer specialists (31% for British and 53% for Canadian cancer specialists versus 27%) [14, 23]. Similarly, we have found that only 24% of Swiss cancer clinicians exhibit reduced feelings of personal accomplishment or self-efficacy, which is also lower than previously reported (respectively, 33% and 48%). On the other hand, we found a prevalence of 21% for depersonalisation, reflecting a cynical or distanced attitudes toward patients, and a prevalence of 34% for psychiatric morbidity, which are in line with previously published works [9, 14, 23, 27].

Previous studies that have often failed to explain burnout scores through specific medical context or patient-related stressors [19, 25]. The inability to identify such associations in previous works has been attributed to the homogeneity of the working contexts, which can impair the identification of relevant risk factors across diverse medical specialties. While performing a systematic comparison focusing on a circumscribed set of occupational factors, we found that burnout was associated with several work characteristics, such as working hours, access to continuing medical education, and type of practice (public vs. private).

Intense workload, especially with long working hours, is considered a relevant risk factor, either as a main element of dissatisfaction [10, 32] or as an inducer of psychological distress and fatigue [26]. Our survey showed that a report of an over 50-h workload per week was associated with a higher risk of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation. Indeed, though cancer clinicians reported higher numbers of worked hours per week, they had a lower risk of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation after adjustment.

We also observed in the present study that physicians mentioning lower levels of continuing education were at higher risk of depersonalisation. As shown by others, the number of hours spent for continuing education is known to have a positive influence on the development of specific skills and knowledge, self-esteem and work-related satisfaction and by time reallocation in resourcing activities [13, 17, 23, 29]. Of note, many cancer clinicians reported to be involved in research and teaching activities, which correlates to higher exposure to continuing education and may explain their relative better resistance to burnout, despite a more important workload.

Finally, we found that physicians working in public institutions expressed, more often, feelings of low accomplishment than their colleagues working in private practice. Results in the literature concerning this distinction are controversial, which may suggest that both types of practice can produce equally satisfying elements (e.g. the variety of work that can be done in academic practice or autonomy coming out of private work) depending on the career options [1]. Despite a much higher proportion of cancer clinicians working in public institutions, adjustment for this characteristic did not change the risk of low personal accomplishment that remained equivalent across the three medical specialties.

In conclusion, when compared to primary care physicians, Swiss cancer clinicians were not at a higher risk to develop burnout. Cancer clinicians displayed lower levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation when compared to general practitioners, after adjustment for differences in workload and access to continuing medical education. Rather surprising, and maybe counter-intuitive, we observed that despite higher numbers of worked hours, cancer clinicians have a lower risk of burnout when compared other doctors. Among possible explanations, their involvement in research and teaching activities and access to continuing education may have protected them against burnout.

Indeed, acquisition of effective communication skills (e.g. open directive questions, delivering bad news with empathy, recognition of cancer patients’ concerns) became mandatory in the postgraduate curricula of Swiss oncologists for nearly 10 years [16]. Without a formal training in stress management, this program may be considered as a buffering factor: it is supposed to have an indirect impact on stress by improving physicians’ feeling of competence and satisfaction and by reducing consequences of poor communication with patients and their families [4, 8, 21].

The protective impact of this specific training may particularly apply to younger cancer clinicians since they are more likely to have been exposed to it. Although we have no information on respondents’ age to preserve strict anonymity, participants from the cancer field have been identified as being ‘younger’ at their workplace compared to paediatricians and general practitioners. Our data suggest that special attention and training in communication skills might compensate for those who have a more limited experience.

However, definitive causal links cannot be definitely drawn because of the cross-sectional nature of our work. Furthermore, age, a possible risk factor for burnout, was not addressed in the survey. As oncology has expanded during the last decade, cancer clinicians might be younger than paediatricians and general practitioners. Therefore, differing age cannot completely be ruled out as a potential confounding factor for burnout across medical specialties. Additional longitudinal studies are needed to better define the respective contribution of specific factors susceptible to explain this difference and clarify the articulation of burnout with mental health.

References

Bell DJ, Bringman J, Bush A, Phillips OP (2006) Job satisfaction among obstetrician–gynecologists: a comparison between private practice physicians and academic physicians. Am J Obstet Gynecol 195:1474–1478

Bettschart W, Plancherel B, Bolognini M (1991) Validation du questionnaire de Goldberg (GHQ) dans un échantillon de population âgée de 20 ans. Psychologie médicale 23:1059–1064

Bovier PA, Martin DP, Perneger TV (2005) Cost-consciousness among Swiss doctors: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res 5:72

Bragard I, Razavi D, Marchal S, Merckaert I, Delvaux N, Libert Y et al (2006) Teaching communication and stress management skills to junior physicians dealing with cancer patients: a Belgian Interuniversity Curriculum. Support Care Cancer 14:454–461

Buddeberg-Fischer B, Dietz C, Klaghofer R, Buddeberg C (2006) Swiss residents’ arguments for and against a career in medicine. BMC Health Serv Res 6:98

Catalan J, Burgess A, Pergami A, Hulme N, Gazzard B, Phillips R (1996) The psychological impact on staff of caring for people with serious diseases: the case of HIV infection and oncology. J Psychosom Res 40:425–435

Dion G, Tessier R (1994) Validation de la traduction de l’inventaire d’épuisement professionnel de Maslach et Jackson. Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement 26:210–227

Favre N, Despland J-N, de Roten Y, Drapeau M, Bernard M, Stiefel F (2007) Psychodynamic aspects of communication skills training: a pilot study. Support Care Cancer 15:333–337

Goehring C, Bouvier Gallacchi M, Kunzi B, Bovier P (2005) Psychosocial and professional characteristics of burnout in Swiss primary care practitioners: a cross-sectional survey. Swiss Med Wkly 135:101–108

Goitein L, Shanafelt TD, Wipf JE, Slatore CG, Back AL (2005) The effects of work-hour limitations on resident well-being, patient care, and education in an internal medicine residency program. Arch Intern Med 165:2601–2606

Goldberg D, Williams P (1991) A user’s guide to the general health questionnaire. NFER-Nelson, Windsor

Graham J (2000) The Kash et al. article reviewed. Oncology (Williston Park) 14:1633–1634

Graham J, Potts HW, Ramirez AJ (2002) Stress and burnout in doctors. Lancet 360:1975–1976 author reply 1976

Grunfeld E, Whelan TJ, Zitzelsberger L, Willan AR, Montesanto B, Evans WK (2000) Cancer care workers in Ontario: prevalence of burnout, job stress and job satisfaction. CMAJ 163:166–169

Kash KM, Holland JC, Breitbart W, Breitbart W, Berenson S, Dougherty J, Ouellette-Kobasa S, Lesko L (2000) Stress and burnout in oncology. Oncology (Williston Park) 14:1621–1633 discussion 1633–1624, 1636–1627

Kiss A (1999) Communication skills training in oncology: a position paper. Ann Oncol 10:899–901

Libert Y, Merckaert I, Reynaert C, Delvaux N, Marchal S, Etienne A-M et al (2006) Does psychological characteristic influence physicians’ communication styles? Impact of physicians’ locus of control on interviews with a cancer patient and a relative. Support Care Cancer 14:230–242

Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter MP (1996) Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd edn. Consulting Psychologist, Palo Alto, CA

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP (2001) Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 52:397–422

McManus IC, Winder BC, Gordon D (2002) The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK doctors. Lancet 359:2089–2090

Merckaert I, Libert Y, Razavi D (2005) Communication skills training in cancer care: where are we and where are we going? Curr Opin Oncol 17:319–330

Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, Cull A, Gregory WM (1996) Mental health of hospital consultants: the effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet 347:724–728

Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, Cull A, Gregory WM, Leaning MS, Snashall DC, Timothy AR (1995) Burnout and psychiatric disorder among cancer clinicians. Br J Cancer 71:1263–1269

Renzi C, Tabolli S, Ianni A, Di Pietro C, Puddu P (2005) Burnout and job satisfaction comparing healthcare staff of a dermatological hospital and a general hospital. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 19:153–157

Schaufeli WB, Enzmann D (1998) The burnout companion to study and practice: a critical analysis. Issues in occupational health. Taylor & Francis, London

Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL (2002) Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 136:358–367

Taylor C, Graham J, Potts HW, Richards MA, Ramirez AJ (2005) Changes in mental health of UK hospital consultants since the mid-1990s. Lancet 366:742–744

Thomsen S, Soares J, Nolan P, Dallender J, Arnetz B (1999) Feelings of professional fulfilment and exhaustion in mental health personnel: the importance of organisational and individual factors. Psychother Psychosom 68:157–164

Travado L, Grassi L, Gil F, Ventura C, Martins C, SEPOS (2005) Physician–patient communication among Southern European cancer physicians: the influence of psychosocial orientation and burnout. Psychooncology 14:661–670

Truchot D (2001) Le burnout des médecins libéraux de Bourgogne. In Edition Dijon: Rapport de recherche pour l’Union Professionnelle des Médecins Libéraux de Bourgogne

Ullrich A, FitzGerald P (1990) Stress experienced by physicians and nurses in the cancer ward. Soc Sci Med 31:1013–1022

Whalley D, Bojke C, Gravelle H, Sibbald B (2006) GP job satisfaction in view of contract reform: a national survey. Br J Gen Pract 56:87–92

Whippen DA, Canellos GP (1991) Burnout syndrome in the practice of oncology: results of a random survey of 1,000 oncologists. J Clin Oncol 9:1916–1920

Williams AP, Barnsley J, Vayda E, Kaczorowski J, ØStbye T, Wenghofer E (2002) Comparing the characteristics and attitudes of physicians in different primary care settings: The Ontario Walk-in Clinic Study. Fam Pract 19:647–657

Acknowledgements

This research project was partly supported by research grants partly from the institutional funds of the Division of oncology and the Department of internal medicine, Geneva University Hospitals and from Amgen Switzerland. We would like to thank Mrs. Paola Pirelli for her administrative work and Dr Jill Graham for giving us methodological indications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arigoni, F., Bovier, P.A., Mermillod, B. et al. Prevalence of burnout among Swiss cancer clinicians, paediatricians and general practitioners: who are most at risk?. Support Care Cancer 17, 75–81 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0465-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0465-6