Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the level of burnout and identify who is at highest risk among healthcare professionals (HCPs) working at the largest referent national institution.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted at the Institute of Oncology and Radiology of Serbia from May 2019 to July 2019, evaluating the level of burnout, depression, fatigue, socio-demographic, behavioral and professional characteristics, and quality of life among healthcare professionals. Of the 576 distributed questionnaires among physicians, nurses/technicians and healthcare coworkers, 432 participants returned their questionnaires (75%). All instruments used in our study had been validated and cross-culturally adapted to Serbian language.

Results

The overall prevalence of burnout was 42.4%, with the greatest proportion of burned out in emotional exhaustion domain (66.9%). The multivariable-adjusted model analysis showed that nurses/technicians had a 1.41 times greater chance of experiencing burnout, compared to physicians (OR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.16–7.10), and that with each year of work experience, the chance of burnout increased by about 2% (OR = 1.02, 95% CI 1.00–1.92). Furthermore, it was shown that, with each point in the PHQ-9 score for depression, probability of burnout increased by 14% (OR = 1.14, 95% CI 1.07–1.94). Finally, after controlling all these potential confounders, the Mental Composite Score of SF-36 score showed an independent prognostic value in exploring the burnout presence among HCPs (OR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.03–2.47).

Conclusion

Our research showed a significant level of burnout among healthcare professionals working in oncology, especially among nurses/technicians. The development of effective interventions at both individual and organizational level toward specific risk groups is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Burnout is an occupational phenomenon that affects the psychological well-being and quality of life of healthcare professionals (Maslach et al. 2001; Shanafelt et al. 2003; Hlubocky et al. 2016) with potential negative impact on patients’ safety and quality of health care (Dyrbye and Shanafelt 2011; Alexandrova-Karamanova et al. 2016; Salyers et al. 2017; Panagioti et al. 2018). It has been defined as a psychological state of emotional exhaustion (loss of enthusiasm for work), depersonalization (cynicism, dehumanization) and reduced personal accomplishment (losing a sense of meaning in work) (Maslach et al. 2001; Murali and Banerjee 2018).

Incidence of burnout among health care professionals (HCPs) has been globally increasing (Shanafelt et al. 2003; Dyrbye and Shanafelt 2011; Hlubocky et al. 2016). Studies have shown many oncologists experience a high level of burnout in the United States, Europe and Australia (Trufelli et al. 2008; Blanchard et al. 2010; Shanafelt and Dyrbye 2012; Medisauskaite and Kamau 2017; Murali and Banerjee 2018). These findings determine that oncologists’ burnout is a recognized problem with a growing call to action (Murali and Banerjee 2018). Within the oncology healthcare team, burnout is highly prevalent among oncology nurses, especially on the emotional exhaustion and low personal accomplishment, while depersonalization is less prevalent in this population (Poghosyan et al. 2010; Cañadas‐De la Fuente et al. 2018). Physicians and nurses encounter many ethical issues and moral dilemmas, especially when a patient is terminally ill (Shanafelt and Dyrbye 2012; Hlubocky et al. 2016; Laor-Maayany et al. 2020). Furthermore, a strong correlation has been documented between burnout and medical errors (Williams et al. 2007; Shanafelt et al. 2010). Various studies have been undertaken to analyze the influence of different socio-demographic and work-related variables on the development of burnout, such as age, sex, parenthood, relationship status, length of employment, administrative tasks, years in oncology practice, academic level, shift work, hours per week devoted to direct patient care, reduced recourses and support (Meier et al. 2001; Escribà-Agüir et al. 2006; Trufelli et al. 2008; Blanchard et al. 2010; Poghosyan et al. 2010; Shanafelt and Dyrbye 2012; Shanafelt et al. 2014; Hlubocky et al. 2016; Banerjee et al. 2017; Murali and Banerjee 2018; Cañadas‐De la Fuente et al. 2018). Additional burden for HCPs are daily responsibilities such as communication regarding cancer diagnoses, treatment decisions, and toxicities, delivering bad news and coping with patients’ emotions, suffering, and death (Espinosa et al. 1996; Isikhan et al. 2004; Medisauskaite and Kamau 2017). Physicians and nurses not only have to respond and care for patients’ needs and emotions, but they need to cope with their own emotional burden often caused by the need to rescue patients, feelings of powerlessness against illness, and grief (Meier et al. 2001; Isikhan et al. 2004; Shanafelt and Dyrbye 2012). All these various factors contribute to development of burnout in HCPs, both at personal and organizational levels (Shanafelt et al. 2003; Dyrbye and Shanafelt 2011; Shanafelt and Dyrbye 2012; Hlubocky et al. 2016).

In Serbia, burnout is still a silent epidemic that receives a small amount of attention from HCPs, government health institutions and the public. Reviewing the international research on this subject, only few studies actually performed a comprehensive analysis of the prevalence of burnout among all members of the multi-professional oncology healthcare team. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the level of burnout and identify who is at highest risk among HCPs working at the largest referent national institution. The results of our study should raise the awareness of burnout among HCPs in oncology, identify vulnerable subgroups, and provoke an urgent call to action.

Materials and methods

Design and sample

A cross-sectional quantitative survey was conducted at the Institute of Oncology and Radiology of Serbia (IORS) from May 2019 to July 2019. This institution is the national referent centre for cancer diagnosis and treatment. All HCPs working at the IORS at the time of investigation were eligible to participate in the study. The total number of HCPs working at the IORS in 2019 was 757, and self-reported anonymous questionnaires were distributed to all departments. Of the 576 distributed questionnaires, 432 were returned. The response rate was 75%. Exclusion criteria for participation in the study were sick leave or holiday during the data gathering period, work discontinuity of more than one year (prolonged studies abroad or prolonged illness), exposure to considerable mental or physical trauma in the previous 6 months (independent of the professional environment). All HCPs provided their written informed consent to participate in this survey. The Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine University of Belgrade, Serbia, approved the design of the study and the consent procedure.

Instruments

The level of burnout among HCPs was assessed with the original 22-item version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) (Maslach et al. 2001). The Maslach Burnout Inventory is widely used as a gold standard instrument for assessing burnout (Maslach et al. 1996). This is the most common, widely described and internationally validated instrument used to assess burnout. For this study, a Serbian cross-culturally adapted and validated version of the MBI-HSS was used (Matejic et al. 2015). This questionnaire assessed burnout across three dimensions. Emotional exhaustion (EE) was measured using nine items, depersonalization (DP) using five, and personal accomplishment (PA) using eight. Each of the 22 items required the respondents to describe, on a 7-point Likert scale, the frequency of experiencing certain feelings related to their work. According to this instrument, high scores relating to EE and DP corresponded to a higher degree of burnout, but a high score in PA corresponded to a lower degree of burnout pertaining to that dimension. Thus, the cut-off scores were defined for each dimension and we adopted the following internationally established definition of burnout: high levels of EE and DP combined with low PA (Maslach et al. 1996). A high level of burnout was defined as a high level of EE (score of 27 or higher), a high level of DP (score of 10 or higher), and a low level of PA (score of 33 or lower). The risk of burnout was defined as follows:

-

High risk: two of the three dimensions beyond the cut-off point;

-

Average risk: one of the three dimensions beyond the cut-off point;

-

Low risk, average or low levels in the EE and DEP dimensions, and high or average levels in the PA.

To increase the sensitivity in estimation of burnout presence among HCPs, only participants with High risk were categorized as those with burnout.

Two questions were asked to evaluate participants’ attitudes toward their current careers and choice of specialty. These questions were as follows: “If you could go back, would you choose medicine as profession all over again?”, and “If you could go back, would you choose an oncology as your selected specialty?”.

Health-related quality of life (QoL) was assessed using the Serbian version of the SF-36 questionnaire. The questionnaire was divided into eight scales: Physical functioning, Role physical, Bodily pain, General health, Vitality, Social functioning, Role emotional and Mental health. Based on these eight domains, two summary scales were made: (1) the Physical Composite Score, comprising Physical functioning, Role physical, Bodily pain and General health and (2) the Mental Composite Score, including Vitality, Social functioning, Role emotional and Mental health. The total QoL score represented the mean value of the Physical Composite and the Mental Composite Scores. Scoring and calculation of scales were performed using the Ware’s survey manual). The scores ranged from 0 as minimum to 100 as maximum, with higher values denoting better functioning and well-being (Ware and Sherbourne 1992).

Fatigue symptoms were quantified using the Serbian version of the Krupp Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), a nine-statement interview where the average score was determined on a seven-point scale. It consisted of 9 items concerning fatigue, on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The suggested cut-off point was 4.0; the FSS had acceptable internal consistency, stability over time and sensitivity to clinical change (Krupp et al. 1989).

The severity of depressive symptoms was quantified using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 incorporates DSM-IV depression diagnostic criteria into a brief self-reporting tool. The first 2 items address anhedonia and depressive mood—symptoms of major depression. These are followed by seven additional items that address changes in sleep, energy, appetite, feeling of guilt and worthlessness, concentration, feeling slowed down or restless, and suicidal thoughts. For each item, the respondents are asked to rate how much they have been bothered by a symptom over the past 2 weeks. Scoring is on a Likert‐type scale from 0 to 3 (0 indicates not at all; 1, several days; 2, more than half the days; 3, nearly every day). The total score for the nine items ranges from 0 to 27, scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 represent the cut-off for mild, moderate, moderately severe and severe depression (Kroenke et al. 2001).

Statistical analysis

Normality was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Data were presented as arithmetic mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as absolute number and percentage for discrete variables. The univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to determine the odds ratio (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), with the aim to explore predictive factors of high burnout risk. A p value of less than 0.05 was chosen as the statistical significance level.

Results

The main socio-demographic, behavioral and health-related professional characteristics of the 432 HCPs are displayed in Tables 1 and 2.

Two questions were asked to evaluate participants’ attitudes toward their current careers and choice of specialty. One of the questions in the structured survey was “If you could go back, would you choose medicine as profession all over again?” Less than half (45.3%) of the respondents replied with a positive answer (“I think YES” and “Absolutely YES”), 29.6% of HCPs were not certain about that choice, while a quarter of participants stated that they would not choose medicine as profession again (“I think NO” and “Absolutely NO”). On the other hand, the same question was repeated regarding the HCPs' attitudes toward working in oncology as their selected specialty. Only 6.8% of HCPs strongly confirmed with “Absolutely YES” and 20.79% with “I think YES” regarding choosing to work in oncology again, while more than one-third of respondents negatively replied to this query.

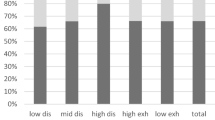

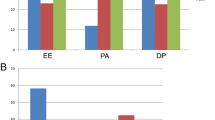

The level of burnout among HCPs was assessed with the MBI-HSS. According to this instrument, high scores relating to EE and DP correspond to a higher degree of burnout, but a high score of PA corresponds to a lower degree of burnout related to that dimension. It was shown that the greatest proportion of high burnout risk was observed in the EE domain (66.9%) and PA domain (47.2%) (Fig. 1). The combination of values in these three MBI-HSS domains determined the final classification of burnout presence. To increase sensitivity, only participants with high risk in two of the three burnout dimensions, values above the cut-off point (EE and DP) and values below the cut-off point (PA), were categorized as those with burnout. With this strict rule in mind, the overall prevalence of burnout among HCPs was 42.4%.

The presence of depression, fatigue and quality of life aspects were also investigated in our HCPs sample in order to estimate their possible confounding effect. Severity of depression symptoms was quantified in all participants with the PHQ-9, and the average reported value was 8.4 ± 6.1. According to the categorization of this score, 70.4% of all participants had at least some mild depressive episodes, while 39 HCPs (6.7%) reported symptoms of severe depression. Fatigue symptoms were quantified using the FSS, with a mean value of 35.4 ± 16.9. Additionally, health-related quality of life was assessed by using the SF-36. The average value of the Physical Composite Score was 63.4 ± 25.4, while the mean value of the Mental Composite Score was 57.0 ± 24.1. The total score of SF-36 was 60.1 ± 23.9.

The predictors of the presence of burnout among HCPs were identified using logistic regression models, illustrated in Table 3. The unadjusted models revealed that significant prognostic value for the presence of burnout had the following variables: age, occupation, oncology departments, duration of work experience in medicine, duration of work experience in oncology, total score of PHQ-9, total score of FSS, the Physical Composite Score, the Mental Composite Score and Total score of SF-36. Furthermore, after testing for variables interaction and controlling the effect of potential confounders, the multivariable-adjusted model demonstrated that independent prognostic value for the presence of burnout among the HCPs working at oncology departments remained significant for occupation, duration of work experience in oncology (years), total score of PHQ-9 and the Mental Composite Score of SF-36. Namely, this analysis showed that nurses and medical technicians had 1.41 times greater chance of burnout compared to physicians (OR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.16–7.10). Additionally, this predictive model demonstrated that with each year of work experience in oncology, the chance of burnout increased by about 2% (OR = 1.02, 95% CI 1.00–1.92). Furthermore, it was shown that with each point in the PHQ-9 score, the probability of burnout increased by 14% (OR = 1.14, 95% CI 1.07–1.94). Finally, after controlling all these potential confounders, the Mental Composite Score of SF-36 score showed an independent prognostic value in exploring the burnout presence among HCPs. Namely, the adjusted logistic regression model revealed that with each one-unit increase in the Mental Composite Scores, the chance of burnout increased by 17% (OR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.03–2.47).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the level of burnout and identify who is at highest risk among HCPs. It was the first one conducted in our country among these professional group, working in different field-specialty oncology departments at the largest national referent institution. Our research revealed a serious problem regarding the prevalence of burnout among HCPs in Serbia.

The results of this study showed that the overall prevalence of burnout in our population of HCPs was 42.4%, which is in accordance with previous international findings among HCPs working in oncology (Trufelli et al. 2008; Blanchard et al. 2010; Shanafelt and Dyrbye 2012; Shanafelt et al. 2014; Gomez-Urquiza et al. 2016; Medisauskaite and Kamau 2017; Murali and Banerjee 2018; Cañadas‐De la Fuente et al. 2018). However, a recent systematic research review of 182 studies, including 109 628 physicians, from 45 countries, demonstrated great inconsistency in published results. The approximations of overall prevalence of burnout ranging from 0 to 80.5% highlighted the importance of developing consensus about the definition of burnout and standardizing assessment instruments (Rotenstein et al. 2018). In March 2020, the ASCO Ethics Committee announced recommendations to address burnout in oncology and support future empirical and interventional burnout research (Hlubocky et al. 2020).

In our study, participants with high risk in two of the three burnout dimensions, values above the cut-off point (EE and DP) and values below the cut-off point (PA), were categorized as those with burnout. With the aim to increase sensitivity of assessment of burnout among this vulnerable cohort, we chose this methodological approach with the High-risk category as cut-off. However, it is important to emphasize that many of our respondents, who were not in this category reported signs and symptoms of burnout. The findings obtained at the Mayo Clinic highlighted high number of physicians with at least one symptom of burnout with significant increasing tendency from 46% in 2011 to 54% in 2014 (Shanafelt et al. 2015). Moreover, the study conducted by Shanafelt et al. (2014) reported a 45% prevalence of burnout among US oncologists’ similar results were also observed in a nationwide cross-sectional study in France (Blanchard et al. 2010). A large European study conducted among young oncologists (< 40 years old) from 41 European countries, emphasized the huge burden of burnout among young oncologist where this value reached up to 70% (Banerjee et al. 2017). This finding pointed out that a substantial number of young oncology-related professionals are already emotionally exhausted. Since it is expected that these HCPs will at least work during the next 20 years, it could be an increasing public-health issue.

Emotional exhaustion (EE) is considered to be the core dimension of burnout (Murali and Banerjee 2018). A multinational study conducted among HCPs from South and South Eastern Europe pointed out high EE to more than 50% among HCPs in Turkey and more than 35% in Greece and Bulgaria (Alexandrova-Karamanova et al. 2016). Our results showed that the greatest proportion of high risk of burnout was observed in EE domain (66.9%), which is in a line with other international studies (Eelen et al. 2014; Gomez-Urquiza 2016; Banerjee et al. 2017). Very high scores of EE among all HCPs working in the field of oncology could be explained by their frequent coping with patients’ deaths, anxiety, suffering during treatment, unrealistic expectations about cancer treatment, delivering bad news, feeling disappointed about cancer treatment limitations, communication with distressed family members (Espinosa et al. 1996; Shanafelt et al. 2003; Isikhan et al.2004; Roth et al. 2011; Leung et al. 2015; Medisauskaite and Kamau 2017).

Our study revealed that a significant prognostic value for the presence of burnout was the occupation and career specialty. The results indicated that medical oncologists are at a greater risk of developing burnout than radiologists and surgical oncologists. International studies focused on assessing burnout among oncology-related specialties reported a prevalence of 28–36% among surgical oncologists, 35% among medical oncologists and 38% among radiation oncologists (Shanafelt and Dyrbye 2012). In our HCP population, burnout is especially prevalent among oncology nurses/technicians. A recent meta-analysis also reported worrying results regarding many oncology nurses with high EE and low PA (Cañadas‐De la Fuente et al. 2018). A study performed in Turkey showed that EE level in nurses was significantly higher than EE among physicians (Alacacioglu et al. 2009). Similarly, our results showed that nurses/technicians had a 1.41 times greater chance of burnout compared to physicians.

The analysis concerning career and satisfaction with the chosen specialty in our study showed distressing results. Less than a half participant reported they would choose medicine as their profession again, while only 30% confirmed they would choose to practice oncology again. The study conducted by Kuerer et al. (2007) showed that burnout in surgical oncologists was associated with reduced satisfaction with career and specialty choice. As shown in our study, the situation regarding the nursing profession and specialty choice is even more alarming. The large European multicenter survey among 23,159 nurses showed that burnout is strongly associated with nurses’ intention to leave their profession. The results of this study showed that 9% of nurses intended to resign due to job dissatisfaction (Heinen et al. 2013).

Several studies analyzed age and work experience as risk factors for burnout among oncology nurses. They reported that young and inexperienced oncology nurses experience less EE and that burnout is more prevalent in those older than 40 (Gomez-Urquiza et al. 2017). Our finding reflects that oncology nurses are subject to greater burnout than other HCPs and that with each year of work in the field of oncology the chance of getting burnout increases by about 2%.

The confounding effect of the presence of depression, fatigue and quality of life was also assessed in our population. Our results showed that 70% of all participants had at least some mild depressive symptoms, while almost 7% of them reported severe depressive episodes, which was closely related to burnout. Namely, it was shown that with each point in the PHQ-9 score, the probability on burnout increased by 14%. A meta-analysis conducted by Medisauskaite and Kamau (2017) demonstrated that 12% of oncologists suffered from depression, while another study among surgical oncologists showed that 5% of them even had suicidal intentions (Balch et al. 2011). Furthermore, the study conducted among members of the society of gynecological oncologists showed that 33% were positive for depression and 13% had a history of suicidal ideation (Rath et al. 2015). Findings of a recent meta-analysis supported this hypothesis showing prevalence of depression among physicians, ranging from 20.9 to 43.2% depending on the instruments used in the research (Mata et al. 2015).

In our study, we also estimated mental and physical aspects of the QoL among HCPs. A study among surgical oncologists also indicated lower physical QoL score as a factor associated with a higher degree of emotional exhaustion and burnout (Kuerer et al. 2007). Another study conducted by Rath et al. (2015) a showed that low mental quality of life score proved to be a factor associated with burnout. In our sample, the average value of the Mental Composite Score was greater compared to the Physical Composite Score indicating a higher contribution of mental aspects for daily living of our participants. Additionally, the predictive model in our study supported this finding. Specifically, it was highlighted that after controlling of all potential confounders, the Mental Composite Score remained an independent prognostic factor for development of burnout. This prognostic equation estimated that with each one-unit increase in the Mental Composite Scores, the chance of burnout increased by 17%.

Limitations and strengths

Some limitations of the present study need to be taken into account during interpretation of results. First, the cross-sectional design of our investigation captures the associations between several variables, but does not inherently allow us to make definite causality conclusions. Therefore, there is no additional information about variations in burden of burnout that potentially occurred between different time points. More frequent monitoring during the follow-up period would provide more information about fluctuations in burnout burden among oncology HCPs and their relationships with selected variables over time. Second, the presence of selection bias might be considered, related mainly to participation bias. Keeping in mind the fact that all data was based on self-report, and while the instruments were validated due to cross-sectional design and self-report information, the observed associations may be overestimated of true ones because of the recall bias. Third, an information bias should be acknowledged, because this study relies on self-reported data, which may be subject to over- or under-estimation, potentially distorting results. Namely, the data in our research were obtained through self-reported questionnaires. Although this approach has many advantages (low price, collecting data in a short period of time, etc.), it is dependent on sincerity of respondents which is generally linked to the nature of questions. Finally, it is very important to mention that comparison of results of different studies that have dealt with this issue is very difficult due to methodological differences and heterogeneity in the criteria used to define and measure burnout, as well as the use of different approaches in scoring and interpretation. However, lack of consensus calls for attention whether the estimated prevalence is interpreted properly. Apart from these limitations, this study has several strengths because it refers to an emerging public health issue and targets a high-risk cohort, expected to be cornerstone in the fight against cancer, although its’ professional-related suffering is obvious. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that such an investigation was conducted for the first time in Serbia, and offered an image of the burnout burden in our health-care settings. We also recruited a representative sample of the HCPs from the largest referent national institution dealing with oncology patients. Thus, we hypothesize that the results of our study could be generalized for the total HCP population in the country.

Conclusion

Our research showed a significant level of burnout among HCPs working at oncology departments, especially among nurses/technicians. Independent prognostic value for the presence of burnout remained significant for occupation, duration of work experience in oncology, total score of PHQ-9 and the Mental Composite Score of SF-36. Ongoing research and further assessment remain of key importance for the development of effective interventions at both individual and organizational level. These results should provide guidance for further research and development of strategies for healthcare professionals working in different field-specialty oncology departments in Serbia. Comprehensive HCPs support programs such as stress management, communication skills training, mindfulness, small-group and team-building activities, counseling and cognitive behavioral therapy can be effective interventions in reducing burnout.

Availability of data and material

We acknowledge that we have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal review the data if requested.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Alacacioglu A, Yavuzsen T, Dirioz M, Oztop I, Yilmaz U (2009) Burnout in nurses and physicians working at an oncology department. Psycho-Oncology 18(5):543–548. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1432

Alexandrova-Karamanova A, Todorova I, Montgomery A et al (2016) Burnout and health behaviors in health professionals from seven European countries. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 89(7):1059–1075

Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Sloan J et al (2011) Burnout and career satisfaction among surgical oncologists compared with other surgical specialties. Ann Surg Oncol 18(1):16–25. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-010-1369-5

Banerjee S, Califano R, de Azambuja E et al (2017) Professional burnout in European young oncologists: results of the European Society For Medical Oncology (ESMO) young oncologists committee burnout survey. Ann Oncol 28:1590–1596. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx196

Blanchard P, Truchot D, Albiges-Sauvin L et al (2010) Prevalence and causes of burnout amongst oncology residents: a comprehensive nationwide cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer 46(15):2708–2715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.014

Cañadas-De la Fuente GA, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Ortega-Campos EM (2018) Prevalence of burnout syndrome in oncology nursing: a meta-analytic study. Psycho-Oncology 27(5):1426–1433. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4632

Dyrbye LN, Schanafelt TD (2011) Physician burnout: a potential threat to successful health care reform. JAMA 305(19):2009–2010. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.652

Eelen S, Bauwens S, Baillon C et al (2014) The prevalence of burnout among oncology professionals: oncologists are at risk of developing burnout. Psycho-Oncology 23(12):1415–1422. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3579

Escribà-Agüir V, Martín-Baena D, Pérez-Hoyos S (2006) Psychosocial work environment and burnout among emergency medical and nursing staff. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 80(2):127–133

Espinosa E, Barón MG, Zamora P et al (1996) Doctors also suffer when giving bad news to cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 4(1):61–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01769878

Gómez-Urquiza JL, Aneas-López AB, De la Fuente EI et al (2016) Prevalence, risk factors, and levels of burnout among oncology nurses: a systematic review. Oncol Nurs Forum 43(3):104–120. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.ONF.E104-E120

Gómez-Urquiza JL, Vargas C, De la Fuente EI et al (2017) Age as a risk factor for burnout syndrome in nursing professionals: a meta-analytic study. Res Nurs Health 40(2):99–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21774

Heinen M, Van Achterberg T, Schwendimann R, Zander B, Matthews A, Kózka M et al (2013) Nurses’ intention to leave their profession: a cross sectional observational study in 10 European countries. Int J Nurs Stud 50(2):174–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.019

Hlubocky FJ, Back AL, Shanafelt TD (2016) Addressing burnout in oncology: why cancer care clinicians are at risk, what individuals can do, and how organizations can respond. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 35:271–279. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_156120

Hlubocky FJ, Taylor LP, Marron JM et al (2020) A call to action: ethics committee roundtable recommendations for addressing burnout and moral distress in oncology. JCO Oncol Practice 16(4):191–199. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.19.00806

Isikhan V, Comez T, Dani MZ (2004) Job stress and coping strategies in health care professionals working with cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nursing 8(3):234–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2003.11.004

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16(9):606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J (1989) The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 46(10):1121–1123. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022

Kuerer HM, Eberlein TJ, Pollock RE et al (2007) Career satisfaction, practice patterns and burnout among surgical oncologists: report on the quality of life of members of the society of surgical oncology. Ann Surg Oncol 14(11):3043–3053. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9579-1

Laor-Maayany R, Goldzweig G, Hasson-Ohayon I et al (2020) Compassion fatigue among oncologists: the role of grief, sense of failure, and exposure to suffering and death. Support Care Cancer 28(4):2025–2031. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05009-3

Leung J, Rioseco P, Munro P (2015) Stress, satisfaction and burnout amongst Australian and New Zealand radiation oncologists. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 59(1):115–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/1754-9485.12217

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP (1996) Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd edn. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

Maslach C, Schaufeli W, Leiter M (2001) Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 52(1):397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N et al (2015) Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 314(22):2373–2383. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15845

Matejić B, Milenović M, Kisić Tepavčević D, Simić D, Pekmezović T, Worley JA (2015) Psychometric properties of the Serbian version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Service Survey: A validation Study among Anesthesiologist from Belgrade Teaching Hospitals. Scient World J. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/903597. http://www.hindawi.com/journals/tswj/2015/903597/ (accessed 10 January 2018)

Medisauskaite A, Kamau C (2017) Prevalence of oncologists in distress: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology 26(11):1732–1740. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4382

Meier DE, Back AL, Morrison RS (2001) The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. JAMA 286(23):3007–3014. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.23.3007

Murali K, Banerjee S (2018) Burnout in oncologists is a serious issue: what can we do about it? Cancer Treat Rev 68:55–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.05.009

Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J et al (2018) Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Med 178(10):1317–1331. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713

Poghosyan L, Clarke SP, Finlayson M, Aiken LH (2010) Nurse burnout and quality of care: cross-national investigation in six countries. Res Nurs Health 33(4):288–298. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20383

Rath KS, Huffman LB, Phillips GS et al (2015) Burnout and associated factors among members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol 213(6):824.e1-824.e8249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.036

Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA et al (2018) Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA 320(11):1131–1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.12777

Roth M, Morrone K, Moddy K et al (2011) Career burnout among pediatric oncologists. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57(7):1168–1173. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.23121

Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L et al (2017) The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 32(4):475–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9

Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN (2012) Oncologist burnout: causes, consequences, and responses. J Clin Oncol 30(11):1235–1241. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7380

Shanafelt TD, Sluan J, Habermann T (2003) The well-being of physicians. Am J Med 114(6):513–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00117-7

Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G et al (2010) Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 251(6):995–1000. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3

Shanafelt TD, Gradishar WJ, Kosty M et al (2014) Burnout and career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol 32(7):678. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.51.8480

Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN (2015) Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 90:1600–1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

Trufelli DC, Bensi CG, Garcia JB et al (2008) Burnout in cancer professionals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care 17(6):524–531. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.00927.x

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30:473–483

Williams ES, Manwell LB, Konrad TR, Linzer M (2007) The relationship of organizational culture, stress, satisfaction, and burnout with physician-reported error and suboptimal patient care: results from the MEMO study. Health Care Manage Rev 32(3):203–212. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HMR.0000281626.28363.59

Funding

This investigation was supported by the Ministry of education, Science and Technological development of the Republic of Serbia (Grant no.175087).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA carried out the study and prepared the manuscript. DK-T was responsible for study design, statistical analysis and interpretation. MN provided interpretation and critical revision of the article. NM was responsible for participant recruitment and study coordination. TP supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict interest.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of University of Belgrade, Serbia (Date: 31.5.2019., No: 1150-V-20).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andrijic, M., Tepavcevic, D.K., Nikitovic, M. et al. Prevalence of burnout among healthcare professionals at the Serbian National Cancer Center. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 94, 669–677 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-020-01621-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-020-01621-7