Abstract

Background

Atypical hemolytic and uremic syndrome (aHUS), a thrombotic micro-angiopathy (TMA) caused by deregulation in the complement pathway, is sometimes due to the presence of anti-complement factor H (CFH) auto-antibodies. The “standard” treatment for such aHUS combines plasma exchange therapy and immunosuppressive drugs. Eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks the terminal pathway of the complement cascade, could be an interesting alternative in association with an immunosuppressive treatment for maintenance regimen.

Case–diagnosis/treatment

We report on two children, diagnosed with mildly severe aHUS due to anti-CFH antibodies, who were treated with the association eculizumab–mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). Neither side effects nor relapses were observed during the 3 years of follow-up; MMF was even progressively tapered and withdrawn successfully in one patient.

Conclusions

The association of eculizumab and MMF appears to be an effective and safe option in pediatric cases of aHUS due to anti-CFH antibodies of mild severity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Atypical hemolytic and uremic syndrome (aHUS), characterized by a deregulation in the complement pathway [1, 2], might be acquired (due to auto-antibodies directed against complement components), especially in youngsters. It induces a significant mortality (16%) and kidney sequelae in almost 50% of survivors [1].

The “standard,” however based on low evidence, treatment for aHUS secondary to anti-complement factor H (CFH) antibodies combines plasma exchange therapy and immunosuppressive drugs [1, 3]. The initial management of aHUS has dramatically improved over the past decade with the use of eculizumab [1, 3,4,5]. As C5-blockers prevent the consequences of anti-CFH antibodies without decreasing their titer, it seems theorically interesting to combine them with an immunosuppressive treatment.

Here, we report on two patients diagnosed with aHUS due to anti-CFH antibodies who were successfully treated by the association of eculizumab–mycophenolate mofetil (MMF).

Cases

Case 1

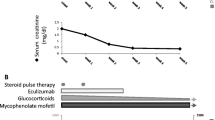

For this 4-year-old boy without medical history, diarrhea first led to the assumption of typical HUS; he was therefore included in the ECULISHU trial (NCT02205541) and received weight-based eculizumab infusions from day 3, according to the study protocol [6]. However, no toxins were found in his stools; both signs of complement activation (C3 0.45g/L, N 0.80–1.50, C4 0.19g/L, N 0.14–0.32, and CH50 34UI/mL, N 41–95) and a significant titer of anti-CFH antibodies (40,500 UA, threshold for significant positivity of 500–1000 UA) confirmed the diagnosis of aHUS. Genetic analysis revealed a classical isolated complete homozygous deletion of CFHR1–CFHR3. The maximum kidney function impairment was observed at day 4 (eGFR 24 mL/min per 1.73 m2), with oliguria and transient arterial hypertension, responsive to diuretic therapy. No kidney replacement therapy was necessary. Two transfusions of red blood cells (day 1 and day 7) and one of platelets (day 1) were required. The patient did not present any extra-renal symptoms. When the result of anti-CFH antibodies was received at day 26, MMF was started. The anti-CFH antibody titer reached non-significance 5 months after diagnosis and eculizumab was thus stopped. As the level of antibodies remained low (< 1000 UA), MMF was decreased and eventually withdrawn 3 years after the onset of disease. With a 1-year follow-up from MMF withdrawal, antibodies are still very low (257 UA), and no relapse has been observed.

Case 2

A 10-year-old girl without significant medical history presented HUS symptoms without bloody diarrhea, during a rhino-pharyngitis episode. An aHUS was suspected because of the association of viral infection and complement activation (C3 0.73 g/L, C4 0.18 g/L, and CH 50 < 14 UI/mL). A significant titer of anti-CFH antibodies (18520 UA) confirmed the diagnosis, and a complete genetic analysis highlighted a homozygous deletion of CFHR1–CFHR3. Neither anti-hypertensive therapy nor kidney replacement therapy was necessary. The patient received two transfusions of red blood cells (day 3 and day 7); no platelet transfusions were necessary. She did not present any extra-renal symptoms. A first eculizumab infusion was administered on day 4 and was followed by weekly weight-based infusions for 3 weeks [6], until maintenance therapy was started, associating eculizumab and MMF. Kidney function and hemolysis normalized within 20 days. Eculizumab infusions were progressively spaced out and withdrawn after 18 months, as both clinical and biological evolutions were favorable (stable anti-CFH antibody titer below 5000 UA). MMF was decreased 4 years after the onset of the disease with a stable level of antibodies around 1000 UA. With a follow-up of 4.5 years, there has been no relapse and antibody levels have remained stable under low MMF therapy. No side effects have been reported.

Figure 1 summarizes the management of these patients. This retrospective series of cases was approved by the local IRB (Comité d’éthique des Hospices Civils de Lyon, session June 7, 2018).

Discussion

We believe that this is the first report of transient eculizumab and MMF therapy combination in pediatric aHUS due to anti-CFH antibodies. Before the eculizumab era, the prognosis of aHUS was poor whatever the cause, leading in pediatrics to chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 5 in 30% and to death in 8–10% of cases [1, 7]. CFH seems to be the most affected complement protein in aHUS: its mutations are found in 20 to 30% of the screened patients and anti-CFH antibodies in about 6 to 10% [8]. A complete homozygous deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3 was found in both our patients, as in most patients presenting anti-CFH antibodies, suggesting a potential pathogenic role in their development [2]. In this setting of aHUS due to anti-CFH antibodies, mortality rates remain between 9 and 16%, at 3 years, 30% of patients are either dead or present CKD stage 5. Immunosuppressive treatments probably prevent the risk of recurrence [1].

All these observations have led to patients with aHUS due to anti-CFH antibodies being treated according to the “standard” first-line treatment [1, 9,10,11], as follows: high doses of corticosteroids associated with early plasma exchange (PE), and sometimes rituximab and cyclophosphamide. This strategy induces a strong and rapidly effective immunosuppression, with a steep decrease in anti-CFH antibody titers at every PE, and stable low antibody titers within 30 to 40 days, followed by a concomitant disappearance of symptoms [12]. Because of the side effects induced by these treatments (and notably cardiovascular morbidity, impaired growth, osteoporosis and mood disorders with corticosteroids, infectious risk with rituximab, decreased fertility, infectious risk and increased tumoral risk with cyclophosphamide) on the one hand, and the significant frequency of kidney sequelae and the higher risk of recurrence rate if immunosuppression is not started or insufficient on the other hand [7, 11], physicians have to find other therapeutic strategies [9]. In this setting, even though eculizumab is expensive and not available in all centers, it seems interesting to use it if available. Indeed, as compared to PE, neither central venous access nor extracorporeal circulation is required, implying fewer complications and improved quality of life.

In the 2016 consensus approach to the management of aHUS in children [1], eculizumab is suggested as a first-line treatment, especially since anti-CFH antibody titers are never obtained immediately. If eculizumab is not available within 24 to 48 h, PE should be preferred. Afterwards, if anti-CFH antibodies are positive, the management depends on the severity of symptoms: if there are severe extra-renal symptoms, a combination of PE, eculizumab infusion (after each PE), and strong immunosuppression with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide or rituximab [1, 2] should be preferred. In contrast, if there are only mild extra-renal symptoms or even exclusive renal symptoms, choosing between eculizumab and PE is reasonable. With PE, an additional strong immunosuppressive regimen (i.e., corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide or rituximab) is recommended; with eculizumab, an empirical “intermediate” immunosuppressive treatment (i.e., adding corticosteroids or MMF) could be considered [1]. Puraswani et al. reported 436 children diagnosed with aHUS due to anti-CFH antibodies. PE was performed in 78% of cases, and immunosuppressive induction or maintenance regimens were performed in 74% of patients [11]. They showed that combining PE and immunosuppressive therapies improved long-term outcomes while maintenance immunosuppression reduced the risk of relapses. As such, they suggested to associate acute primary care with maintenance immunosuppression for 2 years from the onset of the disease [11].

For our patients presenting mild TMA symptoms, we chose to use the recommended weight-based eculizumab doses, without any adjustment to kidney function, combined with MMF [1]. Since the evidence level of such a treatment is low, we targeted the same area under the curve (AUC) than the one used for other kidney diseases: MMF was introduced at 600 mg/m2 twice daily and secondarily adapted to obtain AUC around 50 mg h/L (45–60 mg h/L), so as to be efficient with tolerable side effects, and particularly digestive disorders and leucopenia, as proposed in nephrotic syndrome [13] and in systemic lupus erythematous [14].

Our management led to a slower decrease of antibody titers (i.e., more than 5 months for our patients vs 1.5 months in the literature with the standard treatment [15]). As there were no signs of recurrence, eculizumab was withdrawn, respectively 9 and 18 months after the onset of the disease. MMF was stopped in patient 1, without any relapse so far. As antibody titers remained significantly positive in patient 2, the recurrence risk seemed higher and led us to maintain a long-term immunosuppression.

The side effects of this eculizumab–MMF association must also be discussed: MMF can cause intestinal disorders, and eculizumab can cause anaphylactic reactions and lower immune response to encapsulated bacteria, making immunizations (especially anti-meningococcal and anti-pneumococcal) mandatory in these patients as well as long-term oral antibioprophylaxis by penicillin V.

Our two patients fully recovered, but the limited number of cases makes it difficult to draw strong conclusions. Data are scarce on pediatric aHUS due to anti-CFH antibodies in the era of eculizumab; as such, the comparison of the benefit–risk ratio of different therapeutic strategies is almost impossible. With these limitations in mind, we may nevertheless hypothesize that the favorable outcomes observed in our two patients are due to an early management targeting both the cause and consequences of the disease, with MMF and eculizumab, respectively. Brocklebank et al. reported seven patients out of 17 pediatric aHUS due to anti-CFH antibodies and genetic variants in the complement pathway. As found in our two patients, three of them displayed homozygous deletion of the CFHR1/CFHR3 complex [5], and of the four patients who were on long-term eculizumab as maintenance therapy, none had relapsed with a mean follow-up of 6.4 years [5]. Conversely, here, we present two patients in whom eculizumab was withdrawn 3 years ago. As such, we think that these two cases bring some novel insights in the field, suggesting that the expensive eculizumab therapy can be withdrawn when anti-CFH titers are stable under MMF therapy. The withdrawal of MMF could even be considered secondarily, but the timing and pre-conditions to achieve it cannot be extrapolated from a single patient.

In conclusion, the association of eculizumab and MMF appears to be an effective and safe option in pediatric aHUS due to anti-CFH antibodies, especially in cases of mild severity.

References

Loirat C, Fakhouri F, Ariceta G, Besbas N, Bitzan M, Bjerre A, Coppo R, Emma F, Johnson S, Karpman D, Landau D, Langman CB, Lapeyraque AL, Licht C, Nester C, Pecoraro C, Riedl M, van de Kar NC, Van de Walle J, Vivarelli M, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, HUS International (2016) An international consensus approach to the management of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in children. Pediatr Nephrol 31:15–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-015-3076-8

Loirat C, Frémeaux-Bacchi V (2011) Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 6:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-6-60

Ariceta G, Besbas N, Johnson S, Karpman D, Landau D, Licht C, Loirat C, Pecoraro C, Taylor CM, Van de Kar N, Vandewalle J, Zimmerhackl LB, European Paediatric Study Group for HUS (2009) Guideline for the investigation and initial therapy of diarrhea-negative hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 24:687–696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-008-0964-1

Diamante Chiodini B, Davin JC, Corazza F, Khaldi K, Dahan K, Ismaili K, Adams B (2014) Eculizumab in anti-factor H antibodies associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatrics 133:e1764–e1768. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-1594

Brocklebank V, Johnson S, Sheerin TP, Marks SD, Gilbert RD, Tyerman K, Kinoshita M, Awan A, Kaur A, Webb N, Hegde S, Finlay E, Fitzpatrick M, Walsh PR, Wong EKS, Booth C, Kerecuk L, Salama AD, Almond M, Inward C, Goodship TH, Sheerin NS, Marchbank KJ, Kavanagh D (2017) Factor H autoantibody is associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in children in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Kidney Int 92:1261–1271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2017.04.028

Eculizumab in Shiga-toxin related hemolytic and uremic syndrome pediatric patients - ECULISHU - full text view - ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02205541. Accessed 11 Dec 2018

Dragon-Durey MA, Sethi SK, Bagga A, Blanc C, Blouin J, Ranchin B, André JL, Takagi N, Cheong HI, Hari P, Le Quintrec M, Niaudet P, Loirat C, Fridman WH, Frémeaux-Bacchi V (2010) Clinical features of anti-factor H autoantibody–associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 21:2180–2187. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2010030315

Noris M, Remuzzi G (2009) Atypical hemolytic–uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med 361:1676–1687. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0902814

Loirat C, Garnier A, Sellier-Leclerc AL, Kwon T (2010) Plasmatherapy in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Semin Thromb Hemost 36:673–681. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1262890

Sana G, Dragon-Durey M-A, Charbit M, Bouchireb K, Rousset-Rouvière C, Bérard E, Salomon R, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Niaudet P, Boyer O (2014) Long-term remission of atypical HUS with anti-factor H antibodies after cyclophosphamide pulses. Pediatr Nephrol 29:75–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-013-2558-9

Puraswani M, Khandelwal P, Saini H, Saini S, Gurjar BS, Sinha A, Shende RP, Maiti TK, Singh AK, Kanga U, Ali U, Agarwal I, Anand K, Prasad N, Rajendran P, Sinha R, Vasudevan A, Saxena A, Agarwal S, Hari P, Sahu A, Rath S, Bagga A (2019) Clinical and immunological profile of anti-factor H antibody associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a nationwide database. Front Immunol 10:1282. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01282

Dragon-Durey MA, Blanc C, Garnier A, Hofer J, Sethi SK, Zimmerhackl LB (2010) Anti-factor H autoantibody-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: review of literature of the autoimmune form of HUS. Semin Thromb Hemost 36:633–640. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1262885

Querfeld U, Weber LT (2018) Mycophenolate mofetil for sustained remission in nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 33:2253–2265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-018-3970-y

Woillard JB, Bader-Meunier B, Salomon R, Ranchin B, Decramer S, Fischbach M, Berard E, Guigonis V, Harambat J, Dunand O, Tenenbaum J, Marquet P, Saint-Marcoux F (2014) Pharmacokinetics of mycophenolate mofetil in children with lupus and clinical findings in favour of therapeutic drug monitoring. Br J Clin Pharmacol 78:867–876. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12392

Loirat C, Frémeaux-Bacchi V (2014) Anti-factor H autoantibody-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: the earlier diagnosed and treated, the better. Kidney Int 85:1019–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2013.447

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Véronique Frémeaux-Bacchi for the genetic explorations performed in the patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

JB received travel grants and honoraria from Alexion.

ALL received travel grants from Alexion and honararia from Alexion (2013, 2014).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Matrat, L., Bacchetta, J., Ranchin, B. et al. Pediatric atypical hemolytic–uremic syndrome due to auto-antibodies against factor H: is there an interest to combine eculizumab and mycophenolate mofetil?. Pediatr Nephrol 36, 1647–1650 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-021-05025-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-021-05025-8