Abstract

Purpose

Whereas the different somatostatin receptor (SSTR) subtypes and the chemokine receptor CXCR4 are known to be expressed in a wide variety of human malignancies, comprehensive data are still lacking for MALT-type lymphomas.

Methods

Overall, 55 cases of MALT-type lymphoma of both gastric and extragastric origin were evaluated for the SSTR subtype and CXCR4 expression by means of immunohistochemistry using novel monoclonal rabbit antibodies. The stainings were rated by means of the immunoreactive score and correlated with clinical data.

Results

While the CXCR4 was detected in 92 % of the cases investigated, the SSTR subtypes were much less frequently present. The SSTR5 was expressed in about 50 % of the cases, followed by the SSTR3, the SSTR2A, the SSTR4 and the SSTR1, which were present in 35, 27, 18 or 2 %, respectively, of the tumors only. Gastric lymphomas displayed a significantly higher SSTR3, SSTR4 and SSTR5 expression than extragastric tumors. A correlation between CXCR4 and Ki-67 expression was seen in gastric lymphomas, whereas primarily in extragastric tumors SSTR5 negativity was associated with poor patient outcome.

Conclusions

The CXCR4 may serve as a promising target for diagnostics and therapy of MALT-type lymphomas, while the SSTRs appear not suitable in this respect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type represents the third most frequent subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the most common type of primary extranodal lymphoma, and accounts for about 50 % of gastric lymphoma. They are usually diagnosed in the sixth decade of life, and there is a slight predominance of the female gender (Cohen et al. 2006). MALT-type lymphomas are most often found in the gastrointestinal tract, but they can also occur in almost every organ and tissue, e.g., in the ocular adnexa, salivary glands, thyroid, thymus, breast, lung and skin (Cohen et al. 2006). They are postulated to arise from post-germinal center memory B cells in response to a persistent stimulation of the immune system due to a chronic bacterial or viral infection or to an autoimmune process (Novak et al. 2011). Hence, in 85–90 % of the cases, gastric MALT-type lymphomas are associated with Helicobacter pylori infection and MALT-type lymphomas of the salivary glands or the thyroid usually arise in conjunction with Sjögren’s syndrome or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (Cohen et al. 2006). Clinically, MALT-type lymphomas are considered an indolent disease, which remains confined to the original environment for a prolonged period of time. Therefore, local treatment modalities such as surgery or radiation are preferentially applied (Cohen et al. 2006; Deinbeck et al. 2013; Nam et al. 2014; Wöhrer et al. 2014). Early-stage gastric disease can be successfully treated by Helicobacter pylori eradication, and in up to 95 % of the cases, complete or at least partial remission can be achieved (Fischbach 2014; Zucca et al. 2013; Zullo et al. 2014; Nakamura and Matsumoto 2015; Raderer et al. 2016). For advanced disease, systemic chemotherapy and treatment with rituximab are recommended (Cohen et al. 2006; Zucca et al. 2013; Fischbach 2014; Wöhrer et al. 2014; Raderer et al. 2016). However, clinical outcomes and response to treatment vary considerably between the patients and there is still a need for new effective therapies especially in advanced-stage disease. Additionally, quite often relapse is observed, in some cases even decades after initial diagnosis. Furthermore, in about 30 % of the cases a dissemination to other MALT sites, lymph nodes or bone marrow has been described and recent evidence suggests that this is not a late event (as commonly thought), but that the disease may often be disseminated already at diagnosis (Raderer et al. 2005, 2006, 2016; Wöhrer et al. 2014). Since the stage of the disease has an important impact on patient prognosis and management, a thorough staging is inevitable in all MALT-type lymphoma patients before the start of therapy. In terms of imaging methods, ultrasound examinations and computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis are recommended, whereas the value of a 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) scanning is discussed controversially, especially in early stages of the disease (Zucca et al. 2013). Since both Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas (like normal lymphatic tissue) have been shown to express somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) (Reubi et al. 1992), in a few studies (but mostly with a small number of patients only) SSTR-based scintigraphy has been evaluated for staging of MALT-type lymphomas, too. All in all, a sensitivity around 60 % and false-negative results in about 40 % were seen (Lugtenburg et al. 2001; Li et al. 2003), with a much higher sensitiveness, however, in extragastric as compared to gastric tumors (Raderer et al. 1999, 2001; Morgensztern et al. 2004; Ferone et al. 2005). On the other hand, a substantial amount of additional lesions could be detected in comparison with the conventional staging methods. Thus, in selected cases SSTR-based imaging may increase diagnostic efficiency when performed in conjunction with other imaging modalities (Lugtenburg et al. 2001; Li et al. 2003). However, additional studies are necessary to further substantiate these findings. This should be accompanied by a thorough evaluation of the expression levels of the different SSTR subtypes in a large series of tumor samples. In this respect, investigations have been performed only in a small set of MALT-type lymphomas on the mRNA level so far (Raderer et al. 1999).

Another promising target structure for diagnostics and therapy in MALT-type lymphoma represents the CXCR4 chemokine receptor. In the adult organism, the CXCR4 is physiologically expressed in stem cells, in hematopoietic cells and in cells of the immune system. The activation of the receptor by its natural ligand, the chemokine CXCL12, leads to the proliferation and directed migration of these cells toward the source of the ligand. Hence, the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis is important for the homing and retention of stem cells and the trafficking of lymphocytes toward the sites of tissue damage or inflammation (Teicher and Fricker 2010). Besides, an overexpression of the CXCR4 has been shown in more than 23 different tumor entities including lymphomas. It has been demonstrated in many studies that an increased CXCR4 expression is associated with rapid tumor progression, early metastasis and poor patient outcome (for data on lymphoma, see, e.g., Durig et al. 2001; Balkwill 2004; Lopez-Giral et al. 2004; Brunn et al. 2007; Deutsch et al. 2008, 2013; Furusato et al. 2010; Mazur et al. 2014; Shin et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2015; Moreno et al. 2015). For targeting of the CXCR4, several antagonists are available (Oishi and Fujii 2012), one of which has even been evaluated for its therapeutic potential in non-Hodgkin lymphomas (Beider et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2015). Besides, the Ga-68-labelled CXCR4 ligand CPCR4-2 has been shown to be excellently suited for CXCR4-based PET diagnostics in different highly proliferative tumor entities like lymphomas (Gourni et al. 2011; Wester et al. 2015). Despite these findings and although many types of tumors have extensively been studied for the expression of the CXCR4 at the protein level, only few studies exist in lymphomas (Brunn et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2015; Moreno et al. 2015; Wester et al. 2015) and (like with the SSTRs) respective data are completely lacking for MALT-type lymphomas.

Thus, in the present study the expression of the five SSTR subtypes (SSTR1, SSTR2, SSTR3, SSTR4 and SSTR5) and the presence of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 were evaluated for the first time in a large set of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded MALT-type lymphoma samples by means of immunohistochemistry (IHC) using novel rabbit monoclonal antibodies. These antibodies, displaying numerous advantages over polyclonal ones, were generated by our group and have been extensively characterized recently (Fischer et al. 2008a, b; Lupp et al. 2011, 2012, 2013).

Materials and methods

Tumor specimens

A total of 64 archived formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples from 55 patients with histologically verified MALT lymphoma were included in the present investigation. From 48 patients 1 sample, from 5 patients 2 samples and from 2 patients 3 samples were available. From the 55 lymphomas investigated, 11 were of gastric and 44 of extragastric origin, comprising tumors from the parotid (n = 30), the submandibular (n = 6) and the thyroid gland (n = 6) as well as from the orbita (n = 2). All samples were provided by the Clinical Institute for Pathology and the Department of Internal Medicine I, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, and had been removed by surgery between 1993 and 2013 at the University Hospital of Vienna (Vienna General Hospital), Vienna, Austria. The clinical data were gathered from the respective patient records (see Supplemental Table 1).

Immunohistochemistry

From the paraffin blocks, 4-µm sections were prepared and floated onto positively charged slides. Immunostaining was performed by an indirect peroxidase labelling method as described previously (Lupp et al. 2001). Briefly, sections were dewaxed, microwaved in 10 mM citric acid (pH 6.0) for 16 min at 600 W and then incubated with the specific primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. For the detection of the SSTRs (except SSTR4) and the CXCR4, rabbit monoclonal antibodies were used (hybridoma cell culture supernatants), which are directed against the respective carboxyl-terminal tail of the different receptors (for detailed information on the clones, epitopes and the dilutions of the antibodies, see Table 1). With respect to the SSTR4, similar but polyclonal antibodies (Gramsch Laboratories, Schwabhausen) were applied. Additional stainings were performed with monoclonal mouse antibodies against the proliferation marker Ki-67 (Table 1). Detection of the primary antibodies was performed using a biotinylated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG, respectively, followed by an incubation with peroxidase-conjugated avidin (Vector ABC “Elite” kit; Vector, Burlingame, CA). Binding of the primary antibodies was visualized using 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) in acetate buffer (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA). Sections were then rinsed, counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin and mounted in Vectamount™ mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

The stainings for the receptors of all sections were scored by means of the semiquantitative immunoreactive score (IRS) according to Remmele and Stegner (1987), multiplying the percentage of positive tumor cells in five gradations (no positive cells [0]; <10 % positive cells [1]; 10–50 % positive cells [2]; 51–80 % positive cells [3]; and >80 % positive cells [4]) with the staining intensity in four gradations (no staining [0]; mild staining [1]; moderate staining [2]; and strong staining [3]). As a result, score values between 0 and 12 were obtained. In case that one patient had more than one tumor slide, an arithmetic mean was calculated from the IRS of each slide. Samples having values ≥3 IRS points were considered positive. With respect to the Ki-67 staining, the percentage of positive nuclei was determined.

Statistics

For statistical analysis, the IBM SPSS statistics program version 22.0.0.0 was used. Because the data were not normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), the Mann–Whitney test, Kendall’s τ-b test, Chi-square test and Spearman’s rank correlation were performed. For survival analysis, the Kaplan–Meier method with a log-rank test was used. A p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Overall, tumors from 17 male and 38 female patients were evaluated in the present investigation. The median age of the patients at diagnosis was 54 years (range 31–87 years). Whereas between tumors of gastric and extragastric origin no difference with respect to patient age was seen, there was a distinct dissimilarity with regard to patient gender. Gastric lymphomas displayed a male (7 male vs. 4 female patients) and extragastric tumors a female predominance (10 male vs. 34 female patients).

According to the Ann Arbor classification, 22 patients had a stage I, 15 patients a stage II, 1 patient a stage III, and 15 a stage IV disease. From two patients, no respective data were available. Whereas all patients with gastric lymphoma were in stage I or II (73 % [n = 8] or 27 % [n = 3] of the cases, respectively), 2 % [n = 1] of the patients with extragastric tumors displayed a stage III and 34 % [n = 15] already a stage IV disease.

Somatostatin and CXCR4 chemokine receptor expression

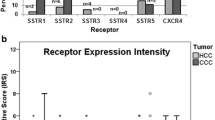

The CXCR4 was by far the most prominent receptor in the MALT-type lymphoma samples investigated (Fig. 1a). It was present in 92 % of the cases at a high intensity of expression (median IRS: 6 points; Fig. 1b). The frequency and intensity of expression of the different SSTR subtypes, in contrast, were quite low. Within the SSTRs, the SSTR5 was the most prominent receptor, displaying an expression in about 50 % of the cases, followed by the SSTR3, the SSTR2A and the SSTR4, which were present in 36, 27 or 18 %, respectively, of the tumors only (Fig. 1a). Also the intensity of expression within the SSTR-positive tumor samples was much lower as compared to the CXCR4-positive cases. Here, the median IRS values solely amounted to 2 points or 1 point, respectively (Fig. 1b). An SSTR1 expression could be detected in one gastric lymphoma only. There was a significant correlation between the SSTR3 and the SSTR4, between the SSTR3 and the SSTR5 and between the SSTR4 and SSTR5 expression intensities (Table 2). No association was seen between the extent of SSTR or CXCR4 expression and the values of the proliferation marker Ki-67. Only when calculating the statistics with the gastric tumors separately, a significant correlation between the CXCR4 and the Ki-67 expression was noticed (r = 0.706; p = 0.015).

Expression profile of the different somatostatin receptor (SSTR) subtypes and of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in MALT-type lymphoma. a Percentage and number of positive cases for the different SSTRs and for the CXCR4. Tumors were only considered positive from an IRS value ≥3. b Box plots of the expression levels (IRS values) of the SSTRs and of the CXCR4. Depicted is the median value, the upper and lower quartile, the minimum and maximum values and outliers

Regarding the receptor combinations observed within the 55 lymphomas investigated, most frequently (with 17 tumors) only a positivity for the CXCR4 was observed, in 10 lymphomas the SSTR5 and the CXCR4 were concomitantly present, in 6 tumors a coexpression of the SSTR2 and the CXCR4 was seen, in 5 cases the combined presence of the SSTR3, the SSTR4, the SSTR5 and the CXCR4 and in 4 tumors the concomitant expression of the SSTR3, the SSTR5 and the CXCR4. In none of the tumors all receptors were simultaneously present, but on the other hand, only one sample was completely SSTR and CXCR4 negative.

As shown in Fig. 2a, the SSTR2 expression was predominantly confined to the germinal centers of the (neoplastic) lymphoid follicles and, here, often present with high intensity, whereas especially the SSTR5 and the CXCR4 were more evenly distributed throughout the tumors. While the immunostaining for the SSTR2 and SSTR3 was predominantly localized at the plasma membrane of the cells, the SSTR1 and SSTR5 displayed both a homogeneous cytoplasmic and a membranous staining (Fig. 2a–c). For the SSTR4, only a cytoplasmic positivity was observed. With respect to the CXCR4, a distinct membranous staining was seen predominantly in the germinal centers of the lymph follicles (Fig. 2d and e, arrowheads), whereas in many cases in the surrounding tumor cells a strong intracellular, dot-like staining was noticed, pointing to a presence in intracellular vesicles and, thus, to a predominant internalization of the receptors (Fig. 2d and f, small arrows).

SSTR and CXCR4 expression pattern in MALT-type lymphomas of gastric and of extragastric origin. Depicted are typical examples for the staining patterns of the SSTR2, the SSTR3, the SSTR5 and the CXCR4. Whereas with the SSTR2 and SSTR3 a predominantly membranous staining was noticed (a, b), the SSTR5 displayed both a cytoplasmic and a membranous expression (c). With respect to the CXCR4, a membranous staining was seen in the germinal centers of the lymph follicles (d, e: large arrowheads), whereas in many cases in the surrounding tumor cells a strong intracellular, dot-like staining was noticed (d, f: small arrows), pointing to a strong internalization of the receptors. Scale bars a = b = c = e = f = 100 µm; d = 250 µm

Comparison between tumors of gastric and extragastric origin

When comparing the different places of origin, tumors of gastric derivation displayed a significantly higher SSTR3, SSTR4 and SSTR5 expression as compared to those of extragastric origin (Fig. 3). A certain tendency toward higher values in gastric lymphomas was also noticed for the CXCR4 (p = 0.101). No differences were seen between gastric and extragastric tumors with respect to the SSTR2A (and SSTR1) expression. Also regarding the Ki-67 level, no statistically significant difference between tumors of gastric or extragastric origin was noticed (median Ki-67 value: gastric tumors: 17.5 %; extragastric tumors: 16.0 %; p = 0.333).

Differential SSTR and CXCR4 expression in MALT-type lymphomas of gastric and extragastric origin. Box plots of the expression levels (IRS values) of the SSTRs and of the CXCR4 separated by gastric and extragastric MALT-type lymphomas. Depicted is the median value, the upper and lower quartile, the minimum and maximum values and outliers

Impact of an infection with Helicobacter pylori or of an autoimmune disease

The presence of Helicobacter pylori, of any autoimmune disease, or of Sjögren’s syndrome or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, respectively, had no impact on the SSTR or CXCR4 expression within the tumors, even when considering gastric or extragastric lymphomas, tumors of the salivary glands or of the thyroid separately. With regard to the Ki-67 values, however, lower values were seen in the tumor samples from patients having an autoimmune disease compared to those without such a disorder both when considering all tumor cases (p = 0.057) and when performing the statistics with extragastric tumors (p = 0.024) or with lymphomas of the salivary glands (p = 0.020) separately.

Correlation with clinical data

From the 11 patients with gastric lymphoma, which were included in the present investigation, none had died during the time period of record, whereas from the 44 patients with extragastric tumor 5 had died in consequence of their tumor and 2 for other reasons.

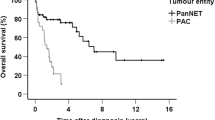

According to the Kaplan–Meier analysis, negativity for the SSTR5 was significantly associated with poor patient outcome. This association was seen both when taking all patients into account (log-rank test: p = 0.038; Supplemental Figure 2) and when considering those with extragastric tumors only (log-rank test: p = 0.075). With the other SSTRs and the CXCR4, in contrast, no such relationship was observed. Besides, a significant negative correlation between the Ki-67 values and overall survival both in all patients and in patients with extragastric tumors only was noticed (all patients: r = −0.219; p = 0.019; extragastric tumors only: r = −0.236; p = 0.024). In extragastric tumors, additionally a significant positive correlation between the Ki-67 values and tumor stage was found (r = 0.245; p = 0.036).

Discussion

Patient characteristics

In comparison with the data of the large epidemiological studies (Cohen et al. 2006; Olszewski and Castillo 2013), the median age of our cohort was slightly lower, with a somewhat higher percentage of extragastric tumors and thus a stronger prevalence of female patients, which is most probably due to the minor number of patients in our study. However, since the discrepancies are small, all in all our cohort of patients can be considered as representative. As shown already in the literature (Raderer et al. 2005, 2006; Ueda et al. 2013), also in the present study a distinctly better outcome was observed with patients with gastric lymphoma as compared to those with extragastric tumors.

Somatostatin and CXCR4 chemokine receptor expression

The SSTRs were clearly of minor importance in the MALT lymphomas investigated. These results are in line with the findings of Dalm et al. (2004) showing no or only a very weak SSTR expression both on the mRNA and on the protein level in a total of 10 samples of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Thus, also according to our results, SSTR-based imaging, radio- or pharmacotherapy cannot be recommended for the routine use in MALT lymphomas. Only in selected cases and when performed in combination with other imaging modalities, SSTR-based imaging may help to enhance diagnostic sensitivity (Lugtenburg et al. 2001; Li et al. 2003). Correspondingly, only in few cases with an immunohistochemically proven at least moderate SSTR expression (i.e., at an IRS >5), SSTR-based treatment attempts may be made. Here, in view of the SSTR expression profile found in the present investigation, pan-somatostatin analogs should be preferred.

In contrast to the SSTRs, the CXCR4 was present in almost all tumors both of gastric and of extragastric origin and mostly at a high intensity of expression. These findings correspond well to the immunohistochemical findings and to the PET/CT data obtained in other lymphoma entities (Brunn et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2015; Moreno et al. 2015; Wester et al. 2015), and they suggest a high significance of the CXCR4 as diagnostic and therapeutic target structure also in MALT lymphomas. Interestingly, with the exception of the (neoplastic) germinal centers, where a predominant membranous staining was seen, in many cases in most of the other tumor cells a strong internalization of the receptor was noticed, pointing to a high level of the natural ligand CXCL12 within these tumors.

In contrast to other lymphoma entities (Durig et al. 2001; Balkwill 2004; Lopez-Giral et al. 2004; Brunn et al. 2007; Deutsch et al. 2008, 2013; Furusato et al. 2010; Mazur et al. 2014; Shin et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2015; Moreno et al. 2015), in the present investigation no correlation between the CXCR4 expression and the tumor stage or patient survival was seen. In gastric tumors, however, a correlation between the CXCR4 expression and the level of the proliferation marker Ki-67 was observed. Additionally, there was a significant association between SSTR5 negativity and poor patient outcome both when considering all MALT lymphomas and the extragastric tumors only, suggesting that the SSTR5 expression may be used also as a prognostic parameter in MALT lymphomas. Since a similar association has also been seen in other tumors entities (see, e.g., Corleto et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2013; Song et al. 2016), this finding should be further substantiated in a larger study population.

Comparison between tumors of gastric and extragastric origin

In contrast to the findings of Raderer et al. (1999) at the mRNA level, in our study tumors of gastric origin displayed significantly higher SSTR3, SSTR4 and SSTR5 expression intensities as compared to the extragastric tumors. This discrepancy between our results and those of Raderer et al. (1999) may be due to either the small sample size investigated by Raderer et al. (6 tumor samples, 4 of which were of gastric and 2 of extragastric origin) or the fact that due to regulatory influences (e.g., expression of miRNAs) not every mRNA is translated into a protein. Our data suggest that (if at all) SSTR-based diagnostics and treatment attempts may be more useful in gastric tumors than in those of extragastric origin.

Conclusions

Due to the high expression rate found in the present investigation, the CXCR4 may serve as a valuable target for diagnostics and therapy in MALT-type lymphomas. The SSTRs, in contrast, are clearly less suitable in this respect. If at all, SSTR-based treatment attempts may be useful in gastric tumors. Beforehand, however, an at least moderate receptor expression has to be proven by immunohistochemistry. Due to the preponderance of the SSTR5 in MALT-type lymphomas, pan-somatostatin analogs should be preferred.

Abbreviations

- SSTR:

-

Somatostatin receptor

References

Balkwill F (2004) The significance of cancer cell expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. Semin Cancer Biol 14:171–179

Beider K, Ribakovski E, Abraham M, Wald H, Weiss L, Rosenberg E, Galun E, Avigdor A, Eizenberg O, Peled A, Nagler A (2013) Targeting the CD20 and CXCR4 pathways in non-Hodgkin lymphoma with rituximab and high-affinity CXCR4 antagonist BKT140. Clin Cancer Res 19:3495–3507

Brunn A, Montesinos-Rongen M, Strack A, Reifenberger G, Mawrin C, Schaller C, Deckert M (2007) Expression pattern and cellular sources of chemokines in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Acta Neuropathol 114:271–276

Chen J, Xu-Monette ZY, Deng L, Shen Q, Manyam GC, Martinez-Lopez A, Zhang L, Montes-Moreno S, Visco C, Tzankov A, Yin L, Dybkaer K, Chiu A, Orazi A, Zu Y, Bhagat G, Richards KL, His ED, Choi WW, van Krieken JH, Huh J, Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Zhao X, Moller MB, Farnen JP, Winter JN, Piris MA, Pham L, Young KH (2015) Dysregulated CXCR4 expression promotes lymphoma cell survival and independently predicts disease progression in germinal-center B-cell like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget 6:5597–5614

Cohen SM, Petryk M, Varma M, Kozuch PS, Ames ED, Grossbard ML (2006) Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Oncologist 11:1100–1117

Corleto VD, Falconi M, Panzuto F, Milione M, De Luca O, Perri P, Cannizzaro R, Bordi C, Pederzoli P, Scarpa A, Delle Fave G (2009) Somatostatin receptor subtypes 2 and 5 are associated with better survival in well-differentiated endocrine carcinomas. Neuroendocrinol 89:223–230

Dalm VASH, Hofland LJ, Mooy CM, Waaijers MA, van Koetsveld PM, Langerak AW, Staal FTJ, van der Lely A-J, Lamberts SWJ, van Hagen MP (2004) Somatostatin receptors in malignant lymphomas: targets for radiotherapy? J Nucl Med 45:8–16

Deinbeck K, Geinitz H, Haller B, Fakhrian K (2013) Radiotherapy in marginal zone lymphoma. Radiat Oncol 8:2

Deutsch AJA, Aigelsreiter A, Steinbauer E, Frühwirth M, Kerl H, Beham-Schmid C, Schaider H, Neumeister P (2008) Distinct signatures of B-cell homeostatic and activation-dependent chemokine receptors in the development and progression of extragastric MALT lymphomas. J Pathol 215:431–444

Deutsch AJA, Steinbauer E, Hofmann NA, Strunk D, Gerlza T, Beham-Schmid C, Schaider H, Neumeister P (2013) Chemokine receptors in gastric MALT lymphoma: loss of CXCR4 and upregulation of CXCR7 is associated with progression to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Modern Pathol 26:182–194

Durig J, Schmucker U, Duhrsen U (2001) Differential expression of chemokine receptors in B cell malignancies. Leukemia 15:752–756

Ferone D, Semino C, Boschetti M, Cascini GL, Minuto F, Lastoria S (2005) Initial staging of lymphoma with octreotide and other imaging agents. Semin Nucl Med 35:176–185

Fischbach W (2014) Gastric MALT lymphoma—update on diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroentreol 28:1069–1077

Fischer T, Doll C, Jacobs S, Kolodziej A, Stumm R, Schulz S (2008a) Reassessment of sst2 somatostatin receptor expression in human normal and neoplastic tissues using the novel rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:4519–4524

Fischer T, Nagel F, Jacobs S, Stumm R, Schulz S (2008b) Reassessment of CXCR4 chemokine receptor expression in human normal and neoplastic tissues using the novel rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-2. PLoS ONE 3:e4069

Furusato B, Mohamed A, Uhlén M, Rhim JS (2010) CXCR4 and cancer. Pathol Int 60:497–505

Gourni E, Demmer O, Schottelius M, D’Alessandria C, Schulz S, Dijkgraaf I, Schumacher U, Schwaiger M, Kessler H, Wester HJ (2011) PET of CXCR4 expression by a (68)Ga-labeled highly specific targeted contrast agent. J Nucl Med 52:1803–1810

Li S, Kurtaran A, Li M, Traub-Weidinger T, Kienast O, Schima W, Angelberger P, Virgolini I, Raderer M, Dudczak R (2003) 111In-DOTA-DPhe1-Tyr3-octreotide, 111In-DOTA-lanreotide and 67Ga citrate scintigraphy for visualisation of extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the MALT type: a comparative study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30:1087–1095

Liu Y, Jiang L, Mu Y (2013) Somatostatin receptor subtypes 2 and 5 are associated with better survival in operable hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma following octreotide long-acting release treatment. Oncol Lett 6:821–828

Lopez-Giral S, Quintana NE, Cabrerizo M, Alfonso-Perez M, Sala-Valdes M, de Soria VG, Fernandez-Ranada JM, Fernandez-Ruiz E, Munoz C (2004) Chemokine receptors that mediate B cell homing to secondary lymphoid tissues are highly expressed in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphomas with widespread nodular dissemination. J Leukoc Biol 76:462–471

Lugtenburg PJ, Löwenberg B, Valkema R, Oei HY, Lamberts SW, Eijkemans MJ, van Putten WL, Krenning EP (2001) Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy in the initial staging of low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. J Nucl Med 42:222–229

Lupp A, Danz M, Müller D (2001) Morphology and cytochrome P450 isoforms expression in precision-cut rat liver slices. Toxicology 161:53–66

Lupp A, Hunder A, Petrich A, Nagel F, Doll C, Schulz S (2011) Reassessment of sst5 somatostatin receptor expression in normal and neoplastic human tissues using the novel rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-4. Neuroendocrinol 94:255–264

Lupp A, Nagel F, Doll C, Röcken C, Evert M, Mawrin C, Saeger W, Schulz S (2012) Reassessment of sst3 somatostatin receptor expression in normal and neoplastic human tissues using the novel rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-4. Neuroendocrinol 96:301–310

Lupp A, Nagel F, Schulz S (2013) Reevaluation of sst1 somatostatin receptor expression in human normal and neoplastic tissues using the novel rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-7. Regul Pept 183:1–6

Mazur G, Butrym A, Kryczek I, Dlubek D, Jaskula E, Lange A, Kuliczkowski K, Jelen M (2014) Decreased expression of CXCR4 chemokine receptor in bone marrow after chemotherapy in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphomas is a good prognostic factor. PLoS ONE 9:e98194

Moreno MJ, Bosch R, Dieguez-Gonzalez R, Novelli S, Mozos A, Gallardo A, Pavon MA, Cespedes MV, Granena A, Alcoceba M, Blanco O, Gonzalez-Diaz M, Sierra J, Mangues R, Casanova I (2015) CXCR4 expression enhances diffuse large B cell lymphoma dissemination and decreases patient survival. J Pathol 235:445–455

Morgensztern D, Rosado MF, Serafini AN, Lossos IS (2004) Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy in MALT lymphoma of the lacrimal gland treated with rituximab. Leuk Lymphoma 45:1275–1278

Nakamura S, Matsumoto T (2015) Treatment strategy of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 44:649–660

Nam TK, Ahn JS, Choi YD, Jeong JU, Kim YH, Yoon MS, Song JY, Ahn SJ, Chung WK (2014) The role of radiotherapy in the treatment of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Cancer Res Treat 46:33–40

Novak U, Basso K, Pasqualucci L, Dalla-Favera R, Bhagat G (2011) Genomic analysis of non-splenic marginal zone lymphomas (MZL) indicates similarities between nodal and extranodal MZL and supports their derivation from memory B-cells. Br J Haematol 155:362–365

Oishi S, Fujii N (2012) Peptide and peptidomimetic ligands for CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4). Org Biomol Chem 10:5720–5731

Olszewski AJ, Castillo JJ (2013) Survival of patients with marginal zone lymphoma: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Cancer 119:629–638

Raderer M, Valencak J, Pfeffel F, Drach J, Pangerl T, Kurtaran A, Hejna M, Vorbeck F, Chott A, Virgolini I (1999) Somatostatin receptor expression in primary gastric versus nongastric extranodal B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type. J Natl Cancer Inst 91:716–718

Raderer M, Traub T, Formanek M, Virgolini I, Österreicher C, Fiebiger W, Penz M, Jäger U, Pont J, Chott A, Kurtaran A (2001) Somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy for staging and follow-up of patients with extraintestinal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)-type. Br J Cancer 85:1462–1466

Raderer M, Streubel B, Woehrer S, Puespoek A, Jaeger U, Formanek M, Chott A (2005) High relapse rate in patients with MALT lymphoma warrants lifelong follow-up. Clin Cancer Res 11:3349–3352

Raderer M, Wöhrer S, Streubel B, Troch M, Turetschek K, Jäger U, Skrabs C, Gaiger A, Drach J, Puespoek A, Formanek M, Hoffmann M, Hauff W, Chott A (2006) Assessment of disease dissemination in gastric compared with extragastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma using extensive staging: a single-center experience. J Clin Oncol 24:3136–3141

Raderer M, Kiesewetter B, Ferreri AJ (2016) Clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment of marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). CA Cancer J Clin 66:152–171

Remmele W, Stegner HE (1987) Recommendation for uniform definition of an immunoreactive score (IRS) for immunohistochemical estrogen receptor detection (ER-ICA) in breast cancer tissue. Pathologe 8:138–140

Reubi JC, Waser B, van Hagen MS, Lamberts WJ, Krenning EP, Gebbers J-O, Laissue AJ (1992) In vitro and in vivo detection of somatostatin receptors in human malignant lymphomas. Int J Cancer 50:895–900

Shin HC, Seo J, Kang BW, Moon JH, Chae YS, Lee SJ, Lee YJ, Han S, Seo SK, Kim JG, Sohn SK, Park T-I (2014) Clinical significance of nuclear factor κB and chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who received rituximab-based therapy. Korean J Intern Med 29:785–792

Song KB, Kim SC, Kim JH, Seo D-W, Hong S-M, Park K-M, Hwang DW, Lee JH, Lee Y-J (2016) Prognostic value of somatostatin receptor subtypes in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas 45:187–192

Teicher BA, Fricker SP (2010) CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res 16:2927–2931

Ueda K, Terui Y, Yokoyama M, Sakajiri S, Nishimura N, Tsuyama N, Takeuchi K, Hatake K (2013) Non-gastric advanced mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma has worse prognosis than gastric MALT lymphoma even when treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy. Leukemia & Lymphoma 54:1928–1933

Wester HJ, Keller U, Schottelius M, Beer A, Philipp-Abbrederis K, Hoffmann F, Simecek J, Gerngross C, Lassmann M, Herrmann K, Pellegata N, Rudelius M, Kessler H, Schwaiger M (2015) Disclosing the CXCR4 expression in lymphoproliferative diseases by targeted molecular imaging. Theranostics 5:618–630

Wöhrer S, Kiesewetter B, Fischbach J, Müllauer L, Troch M, Lukas J, Mayerhofer ME, Raderer M (2014) Retrospective comparison of the effectiveness of various treatment modalities of extragastric MALT lymphoma: a songle-center analysis. Ann Hematol 93:1287–1295

Zucca E, Copie-Bergmann C, Ricardi U, Thieblemont C, Raderer M, Ladetto M, on behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Working Group (2013) Gastric marginal zone lymphoma of the MALT type: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 24(Suppl 6):vi144–vi148

Zullo A, Hassan C, Repici A, Manta R, Andriani A (2014) Gastric MALT lymphoma: old and new insights. Ann Gastroenterol 27:1–7

Author’s contributions

Daniel Kaemmerer and Amelie Lupp conceived and designed the experiments; Ingrid Simonitsch-Klupp, Barbara Kiesewetter and Markus Raderer provided the tumor samples; Stefan Schulz provided the antibodies; Susann Stollberg and Amelie Lupp performed the experiments; Susann Stollberg, Elisa Neubauer and Amelie Lupp analyzed the data; Amelie Lupp wrote the paper; each of the authors has approved the manuscript and acknowledges that he or she participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for its content.

Funding

The Theranostic Research Center, Zentralklinik Bad Berka, 99437 Bad Berka, Germany, provided funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Daniel Kaemmerer received funding and support for travelling to meetings by the companies Ipsen and Pfizer. All other authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Permission was gained from the local ethics committees both in Jena/Bad Berka and in Vienna for this retrospective analysis. Informed consent for the use of tissue samples for scientific purposes was obtained from all individual participants included in the study when entering the University Hospital of Vienna.

Additional information

Susann Stollberg and Daniel Kämmerer have contributed equally to the first authorship.

Markus Raderer and Amelie Lupp have contributed equally to the last authorship.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00432-016-2312-3.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

432_2016_2220_MOESM1_ESM.tif

Supplemental Figure 1. Overall survival of patients with extragastric and with gastric MALT-type lymphoma. Kaplan–Meier survival plot; extragastric tumors n = 44, gastric tumors n = 11; log-rank test: p = 0.366. (TIFF 3676 kb)

432_2016_2220_MOESM2_ESM.tif

Supplemental Figure 2. Overall survival of MALT-type lymphoma patients with either no SSTR5 expression or with SSTR5 positivity of the tumor. Kaplan–Meier survival plot; n = 55; log-rank test: p = 0.038. (TIFF 3676 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stollberg, S., Kämmerer, D., Neubauer, E. et al. Differential somatostatin and CXCR4 chemokine receptor expression in MALT-type lymphoma of gastric and extragastric origin. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 142, 2239–2247 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-016-2220-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-016-2220-6