Abstract

Purpose

Sialolithiasis is the most common cause of chronic sialadenitis. In this case report, intraoperative finding of an accessory submandibular duct, obstructed with stone, originating from the same gland nearby the main Warthon’s duct, is presented.

Case report

A 22-year-old male patient, suffering from eating-related pain and swelling in his left submandibular region, was diagnosed with left sublandibular gland sialadenitis with radiologically manifested sialolithiasis, and gland excision was advised. Surgery was performed under general anesthesia. When the full anatomical scenery was delineated before excision of the gland, we surprisingly encountered two submandibular ducts originating from ipsilateral gland, one of them was obstructed with stone. After two ducts were ligated, the gland with sialolith was excised. According to histopathologic examination, the duct obstructed with stone was identified as the accessory duct and the other one was the main Wharton’s duct. Postoperative days were uneventful; no neurologic complication was observed.

Conclusions

Otolaryngologists should be aware of anatomic variations of the submandibular duct(s) to avoid possible complications, especially intraoperatively, because rutine preoperative radiologic preparation does not include investigation of possible accessory ducts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Surgeries regarding submandibular gland are widely performed in otorhinolaryngology practice. Common reasons for gland surgery are chronic sialadenitis, sialolithiasis, a primary neoplastic process, or enlargement of periglandular lymph nodes which are mostly inseparable from the gland. When compared with parotid gland, primary tumors of the submandibular gland are infrequent; however, chronic inflammation with or without sialolith occurs more frequently in the submandibular gland [2].

The annual incidence of sialolithiasis has been reported in the range of 1/30,000–1/10,000 [11]. However, it has still an unclear etiology. As a general approach to the disease, it is believed that salivary stasis or decreased salivary flow causes the development of stones [6]. The main risk factors are reduced fluid intake, any reason for dehydration, smoking, long illness, diuretics, and drugs that reduce saliva [7, 13].

The accessory duct of submandibular gland is a rare entity. To date, a few reports indicating an accessory duct of the submandibular gland are available [4, 5, 12]. This anomaly is usually found as a duplication of the main Wharton’s duct, with the same or separate opening in the oral cavity. In this case report, we aimed to present a more unusual situation: an accessory submandibular duct obstructed with stone.

Case report

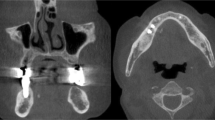

A 22-year-old male patient, suffering from eating-related pain and swelling in his left submandibular region for 5 years, admitted to our clinic to request a radical solution regarding his complaint. Ultrasonography has showed a stone of 7.5 mm in size in the beginning part of the left submandibular duct with increased heterogeneity of submandibular gland, and the computed tomography has confirmed the sialolithiasis (Fig. 1). Gland excision was offered to the patient. Surgery was performed under general anesthesia. When the full anatomical scenery was delineated before excision of the gland, we surprisingly encountered two submandibular ducts originating from single gland, one of them was obstructed with stone (Fig. 2). We also identified the lingual and hypoglossal nerves in their normal anatomic positions. Both two ducts were ligated, and then the gland with sialolith was excised. The histopathological examination was reported as a chronic sialadenitis and sialolithiasis of the submandibular gland with two ducts; the duct obstructed with stone was identified as the accessory duct and the other one was the main Wharton’s duct. One day after the surgery, the patient was discharged on without any complaints or complications. Written informed consent was also obtained from the patient who is presented in this paper.

Discussion

Current literature offers few reports regarding accessory ducts of submandibular gland [4, 5, 12]. The present paper shows more different situation, a sialolithiasis of an accessory submandibular duct. When we encountered two ducts intraoperatively, it was not possible to identify which the main Wharton duct was, and which the accessory duct was. Both two ducts were ligated, and the gland was sent to pathology with its two ducts. According to histopathological examination, the duct obstructed with stone was identified as the accessory duct. The question why the stone in the accessory duct causes obstructive complaints such as food-related pain and swelling despite the presence of main Wharton duct may be best explained as the accessory duct was providing the main secretion of the gland rather than Wharton duct. In our case, two ducts were beginning separately from the gland, but no secondary opening was found in the mouth. Since the examination of the patient’s oral cavity showed only one opening at the floor of mouth, it may be suggested that two ducts come together and combine at anywhere before opening in the oral cavity. Therefore, two ducts were originating from the submandibular gland, but only one opening was present in the mouth. Another possibility that should be taken into consideration, there was another opening in the mouth, but we could not identify that one. As an interesting example of this situation, Gaur et al. reported the submandibular gland having three ducts with three intraoral separate openings [5]. In some cases, it is also possible that the accessory duct can be duplication of the main Wharton’s duct, and this duplication can be located in the beginning of Wharton duct, in the deep side of the gland. Whether there is another opening in the mouth or not, the two ducts were beginning separately in our patient, so duplication is not considered.

Repeated attacks of inflammatory process due to calculus in the Wharton’s duct leads chronic intermittent obstruction with enlargement of the gland and increase in size of stone. The submandibular duct is not elastic, and therefore, when obstructed causes pain. If the stone located in the Wharton’s duct presents itself in the oral cavity, and is obviously palpable, then the stone may be extracted intraorally by a minimal mucosa incision on the duct line [3].

Ultrasonography (USG) is an important first-line diagnostic method for sialolithiasis. In most cases, USG alone is sufficient for preoperative preparation. In this case, USG showed the presence of stone nearby the submandibular gland, but no information was obtained regarding duct(s). Computed tomography (CT) of submandibular gland is very accurate in assessing the location and is helpful for the location of sialolith. Sialography is rarely indicated. It is sometimes possible to assist the surgeon in surgery planning. Since the procedure itself may precipitate an attack of acute sialadenitis, it should be used carefully. It is suggested that the magnetic resonance (MR) sialography should be used in future studies to clarify the course of the accessory salivary duct and other possible ducts [8]. However, this radiologic method is not cost effective and not used in the standard management of sialoliths. In our case, the routes of two ducts from submandibular gland to oral opening could be best demonstrated by MR sialography before surgery; however, rutine preoperative radiologic preparation does not include investigation of possible submandbular gland ducts. In addition, no specific finding was present to support any accessory duct before the surgery. Since it is not a standard procedure to perform further radiologic diagnostic tools such as MR sialography in every “sialolithiasis case”, otolaryngologists will encounter anatomic variations and possible surprises intraoperatively.

The most likely neural complications during surgery are marginal mandibular, lingual and hypoglossal nerve injuries. Anatomical variations or anomalies of the submandibular duct may make surgeon’s work difficult in identifying nerves. Even there is only one duct from submandibular gland as in normal anatomy of the gland, surgeons perform tiny dissections nearby the gland to avoid neural and vascular complications. If there are multiple ducts originating from the submandibular gland, the level of attention during surgery should be increased, because surgeon should dissect multiple ducts this time. In addition, due to the presence of multiple ducts, unrecognition of other ducts may result in unligated or damaged accessory ducts, which leads to complaints due to residual gland ducts. The most possible complications are neck infection and fistula. In addition, in case of re-operation of the neck for any reason, unrecognized residual duct in previous surgery may impair the anatomy in the second surgery. We suggest that surgeons should look for anatomic variations of the submandibular duct(s) during gland excision to avoid these complications. If there is suspicion for anatomic variations, MR sialography is indicated.

In terms of histologic features, there are no differences between main and accessory ducts, and pathologic disorders of the main ducts may also occur in the accessory duct [1, 10]. In the sixth week of embriologic period, the submandibular glands begin to appear as cellular cords on each side under the tongue. The duct grows backward and then turns ventrally near the angle of the mandible branching into smaller ducts. The terminal cell clusters change to the secreting acinar cells. Meanwhile, surrounding mesenchyme creates the stroma of the gland and divides the gland into lobules. It is likely that the accessory ducts may develop from a premature development of an acinar system. When drainage begins to occur with these small canaliculi instead of a main duct, the accessory duct may develop as an independent duct [9].

Conclusion

The presence of two salivary ducts from single submandibular gland, one of which was obstructed by stone, is a very rare entity. Otolaryngologists should be aware of anatomic variations of the submandibular duct(s) especially intraoperatively to avoid possible neural complications regarding lingual and hypoglossal nerves, and to prevent possible future complaints due to residual gland duct. When required, MR sialography may be used.

References

Batsakis JG (1986) Heterotopic and accessory salivary tissues. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 95:434–435

Bodner L (2002) Giant salivary gland calculi: diagnostic imaging and surgical management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 94:320–323

Eun YG, Chung DH, Kwon KH (2010) Advantages of intraoral removal over submandibular gland resection for proximal submandibular stones: a prospective randomized study. Laryngoscope 11:2189–2192

Gadodia A, Seith A, Neyaz Z, Sharma R, Thakkar A (2007) Magnetic resonance identification of an accessory submandibular duct and gland: an unusual variant. J Laryngol Otol 121:122

Gaur U, Choudhry R, Anand C, Choudhry S (1994) Submandibular gland with multiple ducts. Surg Radiol Anat 16:439–440

Harrison JD (2009) Causes, natural history, and incidence of salivary stones and obstructions. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 42:927–947

Huoh KC, Eisele DW (2011) Etiologic factors in sialolithiasis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 145:935–939

Karaca Erdogan N, Altay C, Ozenler N, Bozkurt T, Uluc E, Dirim Mete B, Ozdemir I (2013) Magnetic resonance sialography findings of submandibular ducts imaging. Biomed Res Int 417052:25

Köybaşioğlu A, Ileri F, Gençay S, Poyraz A, Uslu S, Inal E (2000) Submandibular accessory salivary gland causing Warthin’s duct obstruction. Head Neck 22:717–721

Kronenberg J, Horowitz A, Creter D (1988) Pleomorphic adenoma arising in accessory salivary tissue with constriction of Stensen’s duct. J Laryngol Otol 102:382–383

Marchal F, Dulguerov P (2003) Sialolithiasis management: the state of the art. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 129:951–956

Pirkl I, Filipovic B, Goranovic T, Simunjak B (2015) Large tonsillolith associated with the accessory duct of the ipsilateral submandibular gland: support for saliva stasis hypothesis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 44:20

Williams MF (1999) Sialolithiasis. Otolaryngol Clin N Am 32:819–834

Author contributions

Each of the authors has contributed to read and approve this manuscript. This manuscript is original and it, or any part of it, has not been previously published; nor is it under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Funding

No funding was received from any organization for this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Binar, M., Gokgoz, M.C., Aydin, U. et al. Chronic sialadenitis due to the stone inside the accessory duct of submandibular gland. Surg Radiol Anat 39, 1165–1168 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-017-1850-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-017-1850-y