Abstract

We construct a relative export price index that adjusts for changes in non-price factors (e.g. quality or taste) and changes in the set of competitors for nine emerging economies (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia and Turkey). The index is calculated using highly disaggregated (6-digit Harmonized System, HS) trade data from UN Comtrade for the period between 1996 and 2012. Our method highlights the crucial importance of non-price competitiveness in assessing emerging countries’ performance on external markets, as well as notable differences in non-price competitiveness dynamics across exporters. China shows a huge gain in international competitiveness due to non-price factors, while the role of the exchange rate in explaining China’s competitive position may have been overstressed. Similarly, Brazil, India and Turkey show discernible improvements in their competitive position when accounting for non-price factors. Oil exports account for strong improvement in Russia’s non-price competitiveness, as well as losses of competitiveness for Indonesia. Mexico’s competitiveness deteriorates prior to 2006 and improves afterwards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Emerging economies account for an ever-increasing share of world trade. According to the CPB World Trade Monitor (December 2013), the share of emerging countries in total world exports was just 32 % in 1996, but 50 % in 2012. This gain in global export market share is largely the consequence of a substantial growth differential between emerging and advanced economies. Over the period 1996–2012, annual real export growth in emerging markets averaged 7.9 % well outstripping the 3.5 % annual performance of advanced countries. Moreover, real export growth in emerging countries outperformed that of advanced countries every year since 1996, with just two exceptions in 1997 and 2010.

In the general discussion, growing world market shares are mainly associated with improving price competitiveness. Hence, policy makers often focus on price measures and aim at achieving a real depreciation of their currency in order to support their exporters. However, real effective exchange rate (REER) statistics do not always support this prediction, especially in the case of emerging economies’ currencies. Although several emerging countries experienced sharp depreciations in late 1990s and early 2000s, these were followed by gradual real appreciation afterwards. Argentina is the only country among large emerging economies whose REER is significantly below levels of the mid-1990s. For other important emerging economies, we observe either a gradually increasing REER (China, Mexico, Chile, India) or sharp real depreciations during a currency crisis with a subsequent overcompensating increase in the REER (Russia, Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia). This evidence suggests that the traditional REER indicator cannot explain the performance of emerging countries and we should add other factors to the analysis.

The REER indicator, initiated by the theoretical framework of Armington (1969) and further developed by McGuirk (1987), relies on a set of restrictive assumptions. One crucial assumption states that consumers’ utility depends solely on consumed quantities, thus attributing no role to product quality or taste. These non-price factors could be the missing element that explains the discrepancy between REER developments and exports performance in emerging countries.

Several recent empirical studies support the importance of non-price factors for the export performance of emerging countries. Khandelwal (2010) combines information on unit values and market shares for products exported to the USA and finds large variation in the quality of emerging countries’ exports between different products. Hallak and Schott (2011) estimate export quality from export unit values, quantities and trade balances, and find contradictory results regarding the quality performance of emerging countries. While some Asian countries improved their quality rank between 1989 and 2003 (Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia), others just retained their place or even lost several positions (China, India, Mexico). Pula and Santabárbara (2011) analyse the quality of Chinese exports to the European Union using Eurostat’s very detailed COMEXT database and conclude that China gained quality relative to other competitors since the mid-1990s.

Our paper contributes to the literature by developing a measure of a country’s competitiveness that takes into account changes in non-price factors. This measure is an adjusted relative export price index and has some similarities with the unit-value-based REER, but in contrast to the REER it is adjusted for changes in quality, taste and variety that occur over time. Our analysis builds on the framework developed by Feenstra (1994a, b) and Broda and Weinstein (2006) for the calculation of variety-adjusted import prices. We extend their approach beyond the effects of variety alone and apply it to export prices. We also modify the approach developed in Benkovskis and Wörz (2012) by re-weighting relative prices according to the respective elasticity of substitution between varieties (putting more weight to price competitiveness in markets with more competition). In spirit of Hummels and Klenow (2005) and Khandelwal (2010), unobserved relative quality or taste is defined here as a function of observable unit values and volumes of exports as well as unobservable elasticities of substitution between varieties. In fact, we capture all factors that make the respective export good more (or less) valuable for consumers and hence affect consumer utility in the importing country. Such factors comprise physical product quality (i.e. purely supplier controlled) as well as labelling and meeting consumers’ tastes (i.e. demand related). As our approach is solely based on the consumer’s utility maximization problem, it is limited to the demand side and cannot be used to distinguish the relative significance of quality and taste. Therefore, we refer to non-price competitiveness rather than calling it the “quality dimension”.

Here, we illustrate the empirical use of the proposed competitiveness measure for a range of globally important emerging markets over the period 1996–2012. Our sample of nine emerging economies (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia and Turkey) represents roughly one-fifth of total world exports.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 summarizes the conventional wisdom with respect to price competitiveness as described by the REER and explains why the real effective exchange rate conceals non-price elements of competitiveness and therefore provides an insufficient picture of a country’s competitiveness. Section 3 outlines our methodological approach to reveal these non-price aspects. Section 4 describes the data from UN Comtrade database and Sect. 5 reports the results. Conclusions are given in Sect. 6.

2 From price to non-price competitiveness

Competitiveness of a country relative to another is often assessed by its real exchange rate, a reflection of relative changes in nominal exchange rates net of differences in inflation rates. Inflation, in turn, can be measured in terms of consumer price index (CPI), producer price index (PPI) or unit labour costs. Beyond bilateral comparisons, competitiveness can also easily be measured through the REER index, a trade-weighted average of all bilateral real exchange rates. While REER calculation is tedious, the necessary data (exchange rates and inflation rates) are readily available.

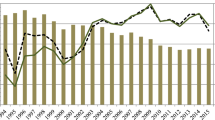

CPI-based real effective exchange rates of emerging countries (172 trading partners, \(2000=100\)). Sources: Darvas (2012). We change Darvas’ (2012) base year of 2007 to 2000 for ease of comparison with our reported results. An increase denotes a real appreciation of the national currency that can be interpreted as a loss of competitiveness

Figure 1 shows CPI-based real effective exchange rates for our nine countries between 1996 and 2012.Footnote 1 Increases reflect real appreciation, so they are associated with losses of international competitiveness. Although the majority of emerging countries from our sample experienced the sharp real devaluation of their currencies in the first half of the sample period (Indonesia and Russia in 1998, Brazil in 1999, Turkey in 2001 and Argentina in 2002), this was overcompensated by subsequent real appreciation in most cases. Indeed, apart from Argentina, the sample countries experience a loss (or at least no gains) in price competitiveness during the 17-year sample period as measured through the CPI-based REER. The increase in relative prices is especially pronounced for Russia, Brazil, Turkey and Indonesia in the second half of our sample period. In Russia’s case, this increase is clearly related to the dominance of energy products in its exports. High oil revenues lead to higher incomes with a consequent upward pressure on inflation and the REER. In Turkey, the disinflation process after the 2001 crisis has supported a long-term appreciation trend with an adverse effect on external price competitiveness. India and China have no clear tendency, although a trend towards rising relative prices emerges in the final years of the sample. All countries show signs of improving or stable price competitiveness in 2009 in the midst of the global financial crisis, while the upward trend in CPI-based REER recommences afterwards.

The above analysis can be criticized for failing to illustrate competitiveness adequately as changes in consumer prices often do a poor job in explaining export performance. Domestic and export prices are the products of largely distinct demand and supply conditions. Moreover, the CPI is subject to changes in indirect taxes (e.g. VAT) that do not affect export prices directly. While the PPI might be a better measure for purely production-related price dynamics, it usually refers primarily to production for the domestic sector, and in most cases, data on export-oriented producer prices are unavailable. Similar caveats apply for unit labour costs as a price measure as these often refer to the whole economy including services, especially in the case of emerging economies.

Our solution is to construct an index for export prices calculated at the most detailed product level available. However, a new problem arises from the use of REERs, which only measure the price competitiveness of exports and ignore important factors such as changes in the quality of exported products (Flam and Helpman 1987), quality that has both an objective (e.g. physical properties and technological features) and a subjective aspect (e.g. consumer tastes, branding and labelling). Consumers also gain utility from the increased product variety that results from international trade. Thus, while for example the CPI or the PPI are adjusted for changes in product quality, neither takes into account the changes in the number of products or product variety available to the consumer.

In response to these challenges, we employ an index that adjusts for quality and the set of competitors to improve on existing measures and disentangle changes in pure price competitiveness from changes in non-price competitiveness (i.e. changes in variety and quality). Specifically, we define “variety” following the Armington assumption (Armington 1969) as products of different origin within the same product category. “Quality” is defined as the tangible and intangible attributes of a product that change the consumer’s valuation of it (Hallak and Schott 2011), i.e. the combination of physical attributes of the product and consumer preferences.Footnote 2

3 Disaggregated approach to measure price and non-price competitiveness

We now describe the disaggregated approach to measure price and non-price competitiveness of exports of emerging countries. Our approach combines the methodology developed by Feenstra (1994a, b) and Broda and Weinstein (2006) with an evaluation of an unobserved quality or taste parameter based on the work of Hummels and Klenow (2005). The insight here is that consumers value physical attributes of products and variety (i.e. the set of exporters in line with the Armington assumption) and that consumer utility depends to a certain extent on the quality or taste preference. By solving this consumer maximization problem, it is possible to introduce non-price factors into a measure for relative export prices (see “Import price index”, “Relative export price index” sections of Appendix, for technical derivations). Having derived a formula for a variety- and quality-adjusted import price index, we then use the mirror image of trade flows to apply this formula to export prices. In other words, we interpret imports of product g originating from country c as country c’s export of product g to the importing country.

Changes in the adjusted relative export price of good g exported to a particular market \((\mathrm{RXP}_{gk,t})\) are defined as

where k denotes a particular emerging country, \(p_{gc,t}\) is the price of good g imported from country c, \(d_{gc,t}\) is the unobservable quality or taste parameter of a corresponding product, \(C_{g}\) is the set of countries exporting a particular product in both periods t and \(t-1, w_{gc,t}(C_{g})\) represents the Sato–Vartia weights of countries exporting a product g in both periods, \(\lambda _{g,t}\) shows the share of new or disappearing exporters, and \(\sigma _{g}\) is elasticity of substitution among varieties (different countries of origin) of good g. Note that \(\mathrm{RXP}_{gk,t}\) shows changes in emerging country k’s adjusted export price relative to the world adjusted export prices.

The index of adjusted relative export prices in (1) can be divided into three parts. The first term gives the traditional definition of changes in relative export prices driven by changes in relative export unit values. These changes in relative unit values are weighted by the importance of competitors in a given market \((w_{gc,t})\) and the respective elasticity of substitution between varieties (putting more weight to price competitiveness in markets with more competition). This particular feature of the relative export price index in (1) makes it superior to the standard REER that assumes a constant elasticity of substitution between any two suppliers (see McGuirk 1987). An increase in relative unit values is to be interpreted as a loss in price competitiveness.

The second term represents Feenstra’s (1994a, b) ratio for capturing changes in varieties. It accounts for the fact that the appearance of a new variety increases consumers’ utility and diminishes the import price index. Even though our framework is based on maximizing consumer utility (and hence on imports), we interpret it from the exporter’s point of view. Thus, variety represents the set of exporters delivering a specific variety of the good and a new variety is tantamount to entry of an additional exporter in the market. If more competitors sell the same product, minimum unit costs are lower and consumers’ utility is increased. At the same time, the market power of each exporter is reduced. Therefore, additional competitors for a specific product imply a positive contribution to the adjusted relative export price index and are associated with a loss in competitiveness.

The third term is simply the change in relative quality or taste preference for a country’s export products. If the quality or taste preference for a country’s exports rises faster than that of its rivals, the contribution to the adjusted relative export price index is negative, thereby signalling an improvement in non-price competitiveness. Although relative quality or consumer tastes are unobservable, it is possible to evaluate it using information on relative unit values and real market shares (see “Evaluation of relative quality” section of Appendix).

Finally, we need to design an aggregate relative export price index as the index in (1) describes relative export prices for a specific product exported to a particular country only. The aggregate-adjusted relative export price index \((\mathrm{RXP}_{k,t})\) for the emerging country k can be defined as a weighted average of specific market indices, where weights are given by shares of those markets in a country’s exports:Footnote 3

where \(W(i)_{g,t}\) represents the Tornqvist weights of specific markets in total export basket.

4 Description of the database

For the empirical analysis in this paper, we use trade data from UN Comtrade. Although the data reported in UN Comtrade have a lower level of disaggregation and longer publication lag than Eurostat’s COMEXT, the worldwide coverage of the UN database is a significant advantage. We use the most detailed level reported by UN Comtrade, which is the six-digit level of the Harmonized System (HS) introduced in 1996. This gives us 5132 products, i.e. enough to ensure a reasonable level of disaggregation.

Although our ultimate goal is to evaluate competitiveness of exports from emerging countries, we start with the import data of partner countries in the analysis. The argument for focusing on partner imports rather than the emerging country’s exports is driven by the theoretical framework on which our evaluation of price and non-price competitiveness is based. Recall that our methodology starts with the consumer’s utility maximization problem. Thus, import data are clearly preferred as imports are reported in CIF (cost, insurance, freight) prices, giving us the cost of the product at the point it arrives at the importer country’s border. From the consumer’s point of view, import data provide a better comparison of prices. On the other hand, import data come with certain drawbacks. Obviously, the data on imports from emerging countries do not necessarily coincide with the country’s reported exports due to differences in valuation, timing, sources of information and incentives to report. That said, and especially with respect to emerging economies, which are still subject to import tariffs for a considerable range of their products, import data are as a rule fairly well reported as national authorities have an interest in the proper recording of imports on which they collect a tariff revenue.

Our import data set contains annual data on imports of 190 countries at the six-digit HS level between 1996 and 2012.Footnote 4 UN Comtrade database contains information on 238 partner countries (exporters); therefore, we obtain complete and detailed information on world trade from the importers’ point of view.

We use unit value indices (dollars per kilogram or other measure of quantity) as a proxy for prices and trade volume (mainly in kg, although other measures of quantity are used for certain products) as a proxy for quantities. If data are missing for values or volumes, or data on volumes is not observed directly but estimated by statistical authorities, a unit value index cannot be calculated. Estimating unit values is complicated for many reporting countries. Even the world’s top importer, the US, only publishes import data that would allow for the calculation of unit values for about 70 % of imports (in value terms). The situation is better for most of the EU countries, China, Japan, while several countries (e.g. Canada) provide coverage around 50 %. Coverage is also generally worse for the first half of the sample period. This problem makes the analysis of non-price competitiveness more challenging and our results should be taken with a grain of salt. However, coverage ratios of available unit values in several countries are rather homogenous across product groups, so we argue that this problem is unlikely to affect our results significantly. The other adjustment we made to the database is related to structural changes within the categories of goods. Although we use the most detailed classification available, it is still possible that we may compare apples and oranges within a particular category. One indication of such a problem is given by large price-level differences within a product code. Consequently, all observations with outlying unit value indices were excluded from the database.Footnote 5

Finally, in order to calculate the weights for the aggregate relative adjusted export price index, we use export data of our nine emerging countries. The export data set reflects the structure of exports adequately and contains annual value data on exports to 238 partner countries at the six-digit HS level between 1996 and 2012.

5 Empirical results for exports of emerging countries

5.1 Estimating elasticities of substitution

Before discussing the relative export price indices of emerging countries, we need to describe the estimation of unobservable elasticities of substitution between varieties \((\sigma _{g})\) that enter the Eq. (1). Following the approach proposed by Feenstra (1994a, b) and developed by Broda and Weinstein (2006), and Soderbery (2010, 2013), we specify a system of demand and supply equations for each individual product g in every importing country. Technical details are provided in “Elasticities of substitution between varieties” section of Appendix.

Table 1 displays the main characteristics of estimated elasticities of substitution between varieties for the top 20 world importers.Footnote 6 The median elasticities of substitution are typically clustered between 2.3 and 3.9: USA (2.28), China (3.04), Germany (3.39). Despite similarities of median elasticities of substitution between varieties across countries, our results signal a remarkable variation in elasticities of substitution across products. Literally, elasticities vary between unity and infinity, meaning that some markets operate under almost perfect competition, while others under monopolistic competition. This highlights a significant potential drawback of the traditional REER, which assumes the same elasticity of substitution for all products.

Table 2 in the Appendix compares our estimates for US imports with the results found in the empirical literature. In addition, we also report our own estimates of \(\sigma _{g}\) for different levels of disaggregation (3- and 5-digit SITC rev. 3). We see that our results are higher than those obtained by Soderbery (2013) using nonlinear LIML, while our estimates are significantly lower than median elasticities reported by Broda and Weinstein (2006) and Mohler (2009). Differences in the sample period fully explain our higher median elasticity compared to Soderbery (2013), since we use the same estimation methodology and a lower level of disaggregation (Table 2 shows that estimates tend to be smaller for more aggregate product groups, as expected). Our sample period includes the dramatic trade collapse in 2008–2009, which may explain higher estimates and signal that elasticities of substitution could vary over time. Besides sample period, differences in estimates with Broda and Weinstein (2006), and Mohler (2009) are also due to the choice of methodology and the level of disaggregation.

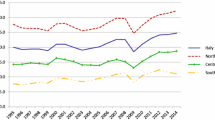

Export prices of emerging countries relative to competitor export prices (2000 = 100). Sources: UN Comtrade, authors’ calculations. Relative export prices are calculated by cumulating RXP changes from Eqs. (1), (2) and (16). Increase denotes losses in competitiveness. RXP starts from 1997 for Brazil, Chile and Russia due to missing of export data in 1996. a Argentina. b Brazil. c Chile. d China. e India. f Indonesia. g Mexico. h Russia. i Turkey

5.2 Relative export prices

When elasticities of substitutions are estimated, we start by calculating a conventional export price index that ignores changes in both the set of competitors and the taste or quality factors. This index is obtained from the first term of (1) and is shown as the solid line in Fig. 2 below. We next augment this index by taking into account exit and entry of competitors in each narrowly defined goods market (adding the second term of (1), dashed line). Finally, we adjust the export price index to include product quality and consumer tastes (using all terms of Eq. (1), line plotted in diamonds).Footnote 7

Compared to the findings based on REERs, we observe weaker gains or losses in price competitiveness for these countries using the conventional export price index, although the patterns are comparable with the one reported in Fig. 1. For Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, Mexico and Turkey both measures show similar dynamics for price competitiveness, although the RXP exhibits smaller fluctuations in the late 1990s. The most significant difference is observed for Argentina, where the RXP in Fig. 2 signals a pronounced loss in price competitiveness since 2006 in contrast to the CPI-based REER which showed no discernible change over the same period. The conventional RXP for India even reports a moderate improvement in price competitiveness since 2001 in contrast to results obtained from the REER. Interestingly, RXP-based evidence for China suggests almost no changes in price competitiveness, although we would have expected to see stronger evidence of rising price competitiveness in China, given frequent claims by its trade partners concerning its undervalued currency.Footnote 8

As all our emerging economies are catching up with their advanced counterparts, we would expect the convergence in income levels to be accompanied by convergence in price levels as observed for emerging economies in central and eastern Europe (Benkovskis and Wörz 2012; Oomes 2005). However, we observe the pronounced trend of falling price competitiveness only for Russia, which can largely be attributed to Russia’s oil income. For example, Égert (2005) finds evidence of a clear “Dutch Disease” pattern for Russia that explains the real appreciation trend. Égert et al. (2003) also points out exchange rate pass-through, oil price shocks and cyclical factors as determinants of inflation in Russia. As an observation from our data, when oil prices collapsed at the beginning of the global economic crisis, prices for Russian exports fell considerably.Footnote 9

Adjusting the index for changes in the set of competitors produces no notable changes—the two lines are almost identical for most countries. The only exception is Indonesia, for which changes in the set of competitors marginally reduce overall competitiveness. Table 3 in the Appendix reveals some notable changes in the average number of competitors faced by emerging economies when exporting a particular product to a particular market. However, one needs to remember that Feenstra’s (1994a, b) ratio accounts for market shares of new and disappearing varieties, not the number of varieties. Thus, our results suggest that emerging countries face a stable set of major rivals, while the changes in the average number of competitors are driven by countries with tiny shares of the market.

Export prices of emerging countries relative to competitors, excluding mineral fuels exports (2000 = 100). Sources: UN Comtrade, authors’ calculations. Relative export prices are calculated by cumulating RXP changes from Eqs. (1), (2) and (16). Increase denotes losses in competitiveness. RXP starts from 1997 for Brazil, Chile and Russia due to missing of export data in 1996. a Argentina. b Brazil. c Chile. d China. e India. f Indonesia. g Mexico. h Russia. i Turkey

However, as soon as we adjust for non-price factors such as quality improvements and changes in consumers’ tastes, the results become more differentiated. The majority of countries in our sample show clear improvements in non-price competitiveness (as reflected in a falling double-adjusted export price index).

China, in particular, stands out. Prices of Chinese goods on international markets fell by more than 40 % since 2000 after correcting for quality improvements and other non-price factors. Among countries in our sample, only Turkey comes close to realizing such a large gain in competitiveness. Indeed, just a few small, highly open transition countries in central, eastern and south-eastern Europe display comparable improvements in non-price adjusted competitiveness over the same period (Benkovskis and Wörz 2012). This suggests that China’s inexorable rise as a trading power—we see China overtake Germany to become the world’s largest exporter in 2009—is based on a combination of non-price factors and an abundance of relatively cheap labour. Our finding here corroborates the earlier results of Fu et al. (2012), who observe weakening price competition and rising importance of non-price factors such as quality and variety for China over the period 1989-2006. They analyse unit prices of imports into the EU, Japan and the USA (a smaller and more homogenous market than in our analysis) and conclude that this trend, if sustained, poses a serious threat to high-income countries. Pula and Santabárbara (2011) come to similar conclusions and state that China’s exports climb up the quality ladder. Our findings also support the view that a revaluation of the exchange rate would only have a limited impact on China’s competitiveness (Mazier et al. 2008; Coudert and Couharde 2007).

The substantial improvement in Russia’s non-price competitiveness observed in our non-price adjusted index tracks primarily oil exports, Russia’s prime export good.Footnote 10 When oil is excluded from the analysis, only a small improvement in non-price competitiveness is observed for Russia (see Fig. 3 in the Appendix). This finding comports with the empirical literature on Russia’s competitiveness. Ahrend (2006) finds that Russia has experienced great increases in labour productivity in its major export sectors, but qualifies this with the observation that these increases in competitiveness are largely limited to a small number of primary commodity and energy-intensive sectors. Robinson (2009) points out Russia’s dependence on oil exports carry a persisting risk of Dutch Disease problems. Subsequently, he argues that political reform is needed to abate this risk (Robinson 2011). Finally, Ferdinand (2007) observes similarities between Russia and China in their orientation towards building on and promoting national industrial champions and the tendency of this approach to foster specialization.

Brazil, Chile and India also show sizable improvements in their non-price adjusted competitiveness, a finding which is robust when oil products are excluded from the analysis. In line with our results, Brunner and Massimiliano (2006) also observe rising unit values for South Asia in their analysis of technology upgrading in this regions. However, they report a closing of the technology gap by the South Asian countries only with respect to Southeast Asia and not with respect to OECD countries. Interestingly, our detailed results for India by trading partnersFootnote 11 show the same pattern only for the first half of our observation period; the picture becomes more differentiated in more recent years with an increase in non-price competitiveness on the US market accelerating from 2005 onwards. We also observe strong rises in price competitiveness vis-á-vis France and the UK. The results for Turkey suggest significant improvements in non-price factors, a finding which is again robust when oil exports are excluded.

We also observe some apparent losses in non-price competitiveness in Indonesia, although the size of these losses is not robust to excluding oil exports.Footnote 12 The non-price competitiveness of Argentina does not affect RXP adjusted by non-price factors when we analyse total exports. However, Fig. 3 in the Appendix reveals that when oil is excluded, Argentina has a moderate positive trend in non-price competitiveness. Finally, Mexico shows some clear signs of weakening non-price competitiveness before 2006, the results are invariant to excluding oil products. Gallagher et al. (2008) mention factors that can explain these losses, such as the decline in public and infrastructure investment in Mexico, limited access to bank credit for export purposes and the lack of a government policy to spur technological innovation. However, we observe gradual improvements in non-price competitiveness of Mexico since 2006.

In contrast to the findings based on REERs, the crisis in 2009 is less visible in these indices. This is to be expected; changes in non-price factors are driven more strongly by structural (i.e. longer-term) factors than exchange rates and consumer prices, which react quickly to changes in global demand conditions. However, there is some evidence of a temporary drop in non-price competitiveness during the crisis. One can observe a fall in non-price competitiveness for Chile, India and Turkey in 2009–2010. This could be both supply and demand driven. On the one hand, emerging countries’ enterprises could have postponed some of their investment projects because of the financial crisis, thus slowing down the process of quality upgrading in their production. On the other hand, the drop in consumers’ disposable income could have shifted demand towards less-qualitative and cheaper products from emerging countries.

5.3 Relative taste or quality by HS sections

In order to gain a better understanding of the reasons behind changes in non-price competitiveness, Table 4 in the Appendix reports sectoral details of the importance of relative taste or quality for the competitiveness of nine emerging countries. We focus on the most important export categories in terms of their share in emerging countries’ exports in 2012 (vegetable products, chemical products, textiles, base metals, machinery and mechanical appliance, vehicles).Footnote 13

As discussed in the previous subsection, we observe the most significant improvement in non-price competitiveness for China—the adjusted RXP is almost half as low as the conventional RXP indicating a strong contribution of non-price factors above and beyond pure price and cost factors or variety effects for China’s competitive position between 2000 and 2012. This result is invariant to including mineral products. Non-price competitiveness gains are of particular importance in vehicles and associated transport equipment, chemicals and base metals. The most pronounced gains in relative taste or quality are observed for machinery and mechanical appliances (constituting more than 40 % of China’s exports). The implications of these enormous gains in China’s international non-price competitiveness have been noted in several recent discussions. For example, Kaplinsky and Morris (2008) assert that the dominance of China in sectors such as textiles and clothing that serve traditionally as early sectors for industrialization not only precludes gains by other emerging countries but shuts down opportunities for less-developed countries even thinking about embarking on an export-led growth strategy in these sectors. Indeed, our results show that China’s dominance in textiles is due in large part to the contribution of non-price factors.

Brazil, India and Turkey—other emerging countries that show discernible improvements in their competitive position due to non-price factors—also perform well in almost all major product sections (except for Turkish vegetable product exports and exports of vehicles from Brazil). The most striking improvements in non-price competitiveness are observed for exports of chemical products from India and Turkey, textiles from Brazil, machinery from Turkey and motor vehicles from India.

The remaining emerging economies in our sample display more heterogeneous results. Argentina, Chile, Indonesia, Mexico and Russia show improvements in non-price competitiveness in some product groups and deteriorations in others. For example, non-price factors positively affected export performance of Indonesian exporters of textiles in contrast to being a drag on Russia’s and Mexico’s textile exports. We find positive effects of non-price factors in this sector also for China, India and Turkey which is in line with general shifts in global production of textiles towards Asian countries.

6 Conclusions

This paper highlights an often-overlooked aspect of international competitiveness in the discussion of emerging economies export strength that traditionally focuses on price competitiveness. The effects of sharp or forced devaluations are frequently discussed (hardly surprising given the long history of currency crises in such economies) and generally follow a narrative that the abundance of relatively cheap labour in these markets provides them with considerable cost advantages. To our knowledge, however, there is no study that explicitly analyses non-price competitiveness in emerging economies within the narrowly defined concept of competitiveness as “a country’s ability to sell goods internationally.”

To fill this gap and go beyond pure price competitiveness, we measure the evolution of competitiveness by relative export prices, allowing for entry and exit of competitors in narrowly defined goods markets and controlling for changes in non-price aspects (e.g. quality or consumer tastes) of exported goods over time. Drawing on our earlier work (Benkovskis and Wörz 2014) that extends the approach developed by Feenstra (1994a, b), Broda and Weinstein (2006), we consider a highly disaggregated data set of global imports and exports at the detailed 6-digit HS level (yielding more than 5000 products) over the period 1996–2012. The sample consists of nine emerging economies (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia and Turkey) that together represent roughly one-fifth of total world exports.

While we also observe some losses in price competitiveness for several countries in our sample when we base our conclusions on traditional export unit values, these losses are less pronounced compared to the results drawn from CPI-based real effective exchange rates. Taking changes in the global set of competitors into account does not alter the picture, which shows that the set of major competitors is fairly stable in any given year. However, as soon as we allow for non-price factors such as changes in the (physical or perceived) quality of exported products, we observe more pronounced trends for individual emerging markets.

Perhaps our foremost finding is that non-price factors have contributed strongly to China’s gains in international competitiveness. Thus, we conclude that China has assumed its dominant role in the global market through non-price factors, as well as other factors such as the size and structure of its labour force. Our results suggest that the role of the exchange rate in explaining China’s competitive position may have been overstressed by some of China’s critics. Further, Brazil, Chile, India and Turkey show discernible improvements in their competitive position. The surprisingly strong non-price related improvement of Russia’s export position is entirely related to developments in the oil sector with mineral products accounting for more than two-thirds of Russian exports in 2012. We also observe moderate losses in non-price competitiveness for Indonesia, which mostly can be ascribed to exports of oil products. When oil is excluded, Argentina shows a moderate positive trend in non-price competitiveness. Finally, we observe a loss in Mexican non-price competitiveness before 2006, confirming earlier findings in the literature; the non-price competitiveness of Mexico restores afterwards, however.

Although our analysis is based on highly disaggregated data and separates price from non-price effects, it still does not yield a comprehensive picture of competitiveness. Competitiveness continues to be a vague concept, and therefore, multiple approaches have to be combined before drawing firmer conclusions. However, our analysis points towards important factors often ignored, mostly because data sources are missing. Our methodology offers a simple—yet theoretically sound—way to look explicitly at price versus non-price adjustments in international competitiveness. Another important issue that emerges is the increasing global integration of production and shifts in geographic patterns of production chains. Internationalization of production implies a diminishing domestic component of exports, so data on gross trade flows are no more an adequate representative of a country’s competitiveness. Combining trade data with information from input–output tables is a potential solution pointing the direction for further research on the value-added content of exports.

Notes

For a description of the calculations, see Darvas (2012).

Remember that our approach is solely based on the consumer’s utility maximization problem and thus limited to the demand side. To differentiate quality stemming from the supply side and demand-side-related taste, one would need to model the behaviour of firms as in Feenstra and Romalis (2014) or use individual product characteristics as in Sheu (2014).

Here, we limit the analysis of competitiveness to stable exports markets (those, where exports are nonzero in both periods t and \(t-1\)). Thus, the paper limits the analysis to the intensive margin of exports. Although we miss some information on emerging countries’ performance by ignoring the extensive margin, this does little damage to our conclusions. Empirical evidence shows that the extensive margin has a small contribution to total export growth. For instance, Amiti and Freund (2010) find that export growth of China was mainly accounted for by high growth of existing products rather than in new varieties. Also Besedes and Prusa (2011) point to the fact that the majority of the growth of trade is due to the intensive rather than the extensive margin. They also stress that export survival for developing countries is shorter than for advanced economies, thus the extensive margin generates less export growth for emerging countries.

The data for some reporting countries are not available in the early years. The major world importers with missing data are Brazil, Chile, Russia and Singapore (1996), Thailand and Saudi Arabia (1996–1998).

The observation is treated as an outlier if the absolute difference between the unit value and the median unit value of the product category in the particular year exceeds five median absolute deviations. The exclusion of outliers does not significantly reduce the coverage of the database. In the majority of cases, less than 2 % of total import value was treated as an outlier.

Results for other countries are available upon request.

We also produce similar calculations for 3- and 5-digit SITC, rev. 3 disaggregation level. Results are available upon request. In general, we find all RXP indices to be robust, and our conclusions are valid for alternative choices of disaggregation level.

Coudert and Couharde (2007) relate this undervaluation to the absence of the Balassa–Samuelson effect in China which can be inferred from the limited degree of currency appreciation despite its strong catching-up performance. The issue of China’s currency undervaluation is not only a hot topic because of large trade imbalances with some advanced countries (most prominently the US) but also within the context of competition among emerging markets. Pontines and Siregar (2012) note the great concern in East Asian countries over relative appreciation against the renminbi and to a lesser extent against the US dollar that points to strong intra-regional price competition. Gallagher et al. (2008) mention Chinese undervaluation as a potential detrimental effect on Mexico’s export performance beyond purely domestic factors.

Given the relatively inelastic demand for oil products in normal times, this deterioration in Russian price competitiveness up to 2008 did not impact notably on Russia’s global market share, a fact well documented in the empirical literature (e.g. Ahrend 2006; Cooper 2006; Porter et al. 2007; Robinson 2009, 2011) and discussed below.

Mineral products, which include gas and oil, accounted for 70 % of Russia’s total exports in 2012.

These results are available from the authors on request.

Mineral products are the most important export category for Indonesia, representing 33 % of total exports in 2012.

Actually, Feenstra’s (1994a) approach also may take into account taste or quality parameter changes, as “\(\ldots \)change in the number of varieties within a country acts in the same manner as a change in the taste or quality parameter for that country’s imports.” Therefore, one can interpret increasing quality as replacement of a low-quality variety by a high-quality variety. Although both approaches lead to the same import price index, the decomposition and interpretation differs in (11) and (14). In order to account for changes in taste or quality, the first term of (11) should be limited to varieties with unchanged taste or quality that were imported in both periods, thus representing “pure” or “quality-adjusted” price changes. However, the set of such stable varieties may be rather small (especially if we interpret \(d_{gc,t}\) as taste). In contrast, the first term of Eq. (13) captures price changes for the wider set of varieties (i.e. the full set of varieties imported in both periods), although the price changes now include the effect of taste or quality. In addition, (13) allows to differentiate changes in variety from changes in taste or quality.

Although the choice of l could be arbitrary in theory, Mohler (2009) shows that estimates are more stable if the dominant supplier (the country exporting the respective product for the most time periods) is chosen.

Equation (17) states that one can proxy relative \(d_{gc,t}\) by other observable variables, but it does not state the dependence.

The independence assumption relies on the assumption that taste or quality do not enter the residual of the relative supply equation \((\delta _{gc,t})\). If this does not hold, errors are not independent since changes in taste or quality enter \(\varepsilon _{gc,t}\). The assumption of the irrelevance for the supply function seems realistic for taste (if we ignore the possibility that taste is manipulated by advertisement; however, advertisement costs can be viewed as fixed, which should reduce the correlation with the error term). But it is difficult to argue that changes in physical quality of a product should not affect the \(\delta _{gc,t}\). The empirical literature did not address this issue until now and the size of induced bias is unclear.

References

Ahrend R (2006) Russian industrial restructuring: trends in productivity. Competitiveness and comparative advantage. Post-Communist Econ 18(3):277–295

Amiti M, Freund C (2010) An anatomy of China’s export growth. In: Feenstra R, Wei S-J (eds) China’s growing role in world trade. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 35–56

Armington P (1969) A theory of demand for products distinguished by place of production. Int Monet Fund Staff Pap 16(1):159–178

Benkovskis K, Wörz J (2012) Non-price competitiveness gains of central, eastern and southeastern European countries in the EU market. Focus Eur Econ Integr 3:27–47

Benkovskis K, Wörz J (2014) How does taste and quality impact on import prices? Rev World Econ 15(4):665–691

Besedes T, Prusa T (2011) The role of extensive and intensive margins and export growth. J Dev Econ 96(6):371–379

Bloningen B, Soderbery A (2010) Measuring the benefits of foreign product variety with an accurate variety set. J Int Econ 82(2):168–180

Broda C, Weinstein D (2006) Globalization and the gains from variety. Q J Econ 121(2):541–585

Brunner HP, Massimiliano C (2006) The dynamics of manufacturing competitiveness in South Asia: an analysis through export data. J Asian Econ 17(4):557–582

Cooper J (2006) Can Russia compete in the global economy? Eurasian Geogr Econ 47(4):407–425

Coudert V, Couharde C (2007) Real equilibrium exchange rate in China: is the renminbi undervalued? J Asian Econ 18(4):568–594

Darvas Z (2012) Real effective exchange rates for 178 countries: a new database. Bruegel working paper 6

Égert B (2005) Equilibrium exchange rates in South Eastern Europe, Russia, Ukraine and Turkey: healthy or (Dutch) diseased? Econ Syst 29(2):205–241

Égert B, Drine I, Lommatzsch K, Rault C (2003) The Balassa–Samuelson effect in central and eastern Europe: myth or reality? J Comp Econ 31(3):552–572

Feenstra R (1994a) New product varieties and the measurement of international prices. Am Econ Rev 84(1):157–177

Feenstra R (1994b) New goods and index numbers: U.S. import prices. NBER working paper 3610

Feenstra RC, Romalis J (2014) International prices and endogenous quality. Q J Econ. doi:10.1093/qje/qju001

Ferdinand P (2007) Russia and China: converging responses to globalization. Int Aff 83(4):655–680

Flam H, Helpman E (1987) Vertical product differentiation and north–south trade. Am Econ Rev 77(5):810–822

Fu X, Kaplinsky R, Zhang J (2012) The impact of China on low and middle income countries, export prices in industrial-country markets. World Dev 40(8):1483–1496

Gallagher K, Moreno-Brid JC, Porzecanski R (2008) The dynamism of Mexican exports: lost in (Chinese) translation? World Dev 36(8):1365–1380

Hallak JC, Schott P (2011) Estimating cross-country differences in product quality. Q J Econ 126(1):417–474

Hummels D, Klenow P (2005) The variety and quality of a nation’s exports. Am Econ Rev 95(3):704–723

Kaplinsky R, Morris M (2008) Do the Asian drivers undermine export-oriented industrialization in SSA? World Dev 36(2):254–273

Khandelwal A (2010) The long and short (of) quality ladders. Rev Econ Stud 77(4):1450–1476

Leamer E (1981) Is it a demand curve, or is it a supply curve? partial identification through inequality constraints. Rev Econ Stat 63(3):319–327

Mazier J, Oh YH, Saglio S (2008) Exchange rates, global imbalances, and interdependence in East Asia. J Asian Econ 19(1):53–73

McGuirk A (1987) Measuring price competitiveness for industrial country trade in manufactures. IMF working paper 87/34

Mohler L (2009) On the sensitivity of estimated elasticities of substitution. FREIT working paper 38

Oomes N (2005) Maintaining competitiveness under equilibrium real appreciation: the case of Slovakia. Econ Syst 29(2):187–204

Pontines V, Siregar R (2012) Fear of appreciation in East and Southeast Asia: the role of the Chinese renminbi. J Asian Econ 23(4):324–334

Porter M, Ketels C, Delgado M, Bryden R (2007) Competitiveness at the crossroads: choosing the future direction of the Russian economy. Center for Strategic Research (CSR), Moscow

Pula G, Santabárbara D (2011) Is China climbing up the quality ladder? estimating cross country differences in product quality using Eurostat’s COMEXT trade database. ECB working paper 1310

Reinsdorf M, Dorfman A (1999) The Sato–Vartia index and the monotonicity axiom. J Econom 90(1):45–61

Robinson N (2009) August 1998 and the development of Russia’s post-communist political economy. Rev Int Polit Econ 16(3):433–455

Robinson N (2011) Political barriers to economic development in Russia: obstacles to modernization under Yeltsin and Putin. Int J Dev Issues 10(1):5–19

Sato K (1976) The ideal log-change index number. Rev Econ Stat 58(2):223–228

Sheu G (2014) Price, quality, and variety: measuring the gains from trade in differentiated products. Am Econ J: Appl Econ 6(4):66–89

Soderbery A (2010) Investigating the asymptotic properties of import elasticity estimates. Econ Lett 109(2):57–62

Soderbery A (2013) Estimating import supply and demand elasticities: analysis and implications. Mimeo, Department of Economics, Purdue University

Vartia Y (1976) Ideal log-change index numbers. Scand J Stat 3(3):121–126

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank anonymous referees, Rudolfs Bems, Chiara Osbat, Tairi Rõõm, and seminar participants at the 10th Emerging Markets Workshop (Oesterreichische Nationalbank), European Trade Study Group 2012 annual conference and EACES Workshop in Tartu for useful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Latvijas Banka or Oesterreichische Nationalbank.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Import price index

1.1.1 Household utility function

We closely follow Broda and Weinstein (2006) and define a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) utility function for a representative household consisting of three nests. At the topmost level, a composite import good and domestic good are consumed:

where \(D_{t}\) is the domestic good, \(M_{t}\) is composite imports and \(\kappa \) is the elasticity of substitution between domestic and foreign good. At the middle level of the utility function, the composite imported good consists of individual imported products:

where \(M_{g,t}\) is the subutility from consumption of imported good \(g, \gamma \) is elasticity of substitution among import goods and G denotes the set of imported goods.

The bottom-level utility function introduces variety and quality into the model. Each imported good consists of varieties (i.e. goods have different countries of origins, so product variety indicates the set of competitors in a particular market). A taste or quality parameter denotes the subjective or objective quality consumers attach to a given product. \(M_{g,t}\) is defined by a non-symmetric CES function:

where \(m_{gc,t}\) denotes quantity of imports g from country \(c, C_{g,t}\) is a set of all partner countries, \(d_{gc,t}\) is the taste or quality parameter and \(\sigma _{g}\) is elasticity of substitution among varieties of good g.

1.1.2 Conventional import price index

After solving the utility maximization problem subject to the budget constraint, the minimum unit-cost function of import good g is defined as

where \(\phi \) denotes minimum unit-cost function of import good \(g, p_{gc,t}\) is the price of good g imported from country \(c, p_{g,t}\) and \(d_{g,t}\) are the corresponding vectors of prices and taste/quality parameters of good g in period t. The price index for good g is defined as a ratio of minimum unit costs in the current period to minimum unit costs in the previous period:

The conventional assumption is that taste or quality parameters are constant over time \((d_{g}=d_{g,t}=d_{g,t-1})\), and the set of varieties is unchanged. The price index is calculated over the set of product varieties \(C_{g}=C_{g,t}\cap C_{g,t-1}\) available both in periods t and \(t-1\), where \(C_{gt}\subset C\) is the subset of all varieties of goods consumed in period t. Sato (1976) and Vartia (1976) show that, for a CES function, the exact price index will be given by the log-change price index

whereby weights \(w_{gc,t}(C_{g})\) are computed using cost shares \(s_{gc,t}(C_{g})\) for the set of product varieties available in periods t and \(t-1\) as follows:

where \(x_{gc,t}\) is the cost-minimizing quantity of good g imported from country c.

1.1.3 Adjusting for changes in varieties

The import price index in (8) ignores possible changes in variety (set of partner countries) and taste or quality. Feenstra (1994a, b) relaxes the underlying assumption that variety is constant. The cost share of imports from country c in total imports of good g in period t is given by:

from which it follows that

where

After taking the summation of (10) over \(c\in C_{g}\) and raising to the power \(1/(\sigma _{g}-1)\):

from which one could obtain

This is the brief proof of the Proposition 1 in Feenstra (1994a, b) and Broda and Weinstein (2006), which posit that if \(d_{g}=d_{g,t}=d_{g,t-1}\) for \(c\in C_{g}=(C_{g,t}\cap C_{g,t-1})\), \(C_{g}\ne \)Ø, then the exact price index for good g is given by

Therefore, the price index derived in (8) is multiplied by an additional term to capture the role of new and disappearing varieties.

1.1.4 Adjusting for changes in taste or quality parameter

The price index in (11) assumes that taste or quality parameters are unchanged for all varieties existing in both periods \((d_{g}=~d_{g,t}=d_{g,t-1})\). Benkovskis and Wörz (2014) further introduce an import price index that allows for changes in taste or quality. The derivation is straightforward and directly follows from Feenstra (1994a, b) and Broda and Weinstein (2006). From (9) we obtain that

After taking the geometric mean of (12) using weights \(w_{gc,t}(C_{g})\) we arrive to

To prove that the last term of (13) equals unity, we take its natural log:

since the sum of cost shares equals unity in both t and \(t-1\). Thus,

Equation (14) can therefore be seen as a more general version of Eq. (11) with an additional term that captures changes in the quality or taste parameter.Footnote 14

Note that (14) does not contradict the Proposition 2 from Feenstra (1994b), which states that even when \(d_{g,t}\) changes over time, a price index in (11) can be interpreted as a ratio of minimum unit costs with constant taste or quality parameters lying between a normalized version of \(d_{g,t-1}\) and \(d_{g,t}\). According to the Proposition 2, one can always find the vector of constant taste or quality parameters for which the exact price index will coincide with price index in (11). Thus, the Proposition 2 does not state that one can evaluate the exact price index by using (11) in the case of \(d_{g,t-1} \ne d_{g,t}\). Rather it provides useful interpretation of obtained price index that still ignores the developments of taste or quality.

1.2 Relative export price index

Equation (14) gives us a formula for a variety- and quality-adjusted import price index. We can easily interpret \(x_{gc,t}\) (imports of product g originating from country c) as country’s c exports of a product g to the importing market (assuming for the moment that there exists only one destination of exports for all exporting countries—the importing country where the representative household resides). From Eq. (9), it follows that the market share of an emerging country k equals to

and we further derive changes in adjusted relative export price as inverse growth of country k’s export market share:

where \(\mathrm{RXP}_{gk,t}\) represents changes in the adjusted relative export price index for an emerging country k, when defined for a single market (exports of good g to a single destination country). We use the inverse growth of the market share in order to keep the usual interpretation of the relative price indicator—an increasing index denotes losses in competitiveness. Combining (14) and (15), we obtain

Finally, we need to design an aggregate relative export price; the index in (1) only describes relative export prices for a specific product exported to a particular market. The assumption of a single destination for exports is relaxed to allow for multiple importing countries. In all these countries, consumers are assumed to be maximizing their utility. All parameters and variables entering the three-layered utility function can differ across countries. If we denote the export price, export volume and relative export price index of a product g exported by emerging country k to country i as \(p(i)_{gk,t}\), \(x(i)_{gk,t}\) and \(\mathrm{RXP}(i)_{gk,t}\) accordingly, the aggregate-adjusted relative export price index can be defined as

where

The aggregate index \((\mathrm{RXP}_{k,t})\) in Eq. (2) is just the Tornqvist index. Its weights are computed using the share of product g exports to country i out of total exports by country k.

1.3 Evaluation of relative quality

The calculation of the adjusted relative export price index in (1) is challenging as relative taste or quality is unobservable. Following Hummels and Klenow (2005), we evaluate unobserved taste or quality from the utility optimization problem, i.e. after taking first-order conditions and transformation into log-ratios, we express relative taste or quality in terms of relative prices, volumes and the elasticity of substitution between varieties as

where k denotes a particular emerging country.

Relative taste or quality, as any relative measure, is highly sensitive to the choice of a benchmark country. The emerging country of interest serves as a benchmark in our analysis. This choice is driven by the design of the RXP index, which compares export prices and quality of an emerging country to weighted world export prices and quality.

1.4 Elasticities of substitution between varieties

We estimate elasticities of substitution between varieties according to the methodology proposed by Feenstra (1994a, b) and later applied by Broda and Weinstein (2006). To derive the elasticity of substitution, one needs to specify both demand and supply equations. The demand equation is defined by re-arranging the minimum unit-cost function from (6) in terms of market share, taking first differences and ratios to a reference country l:Footnote 15

where \(\varepsilon _{gc,t}=\Delta \hbox {ln}d_{gc,t}+\xi _{gc,t}\), and \(\xi _{gc,t}\) is an error term (e.g. a measurement error) in the demand equation. Following Feenstra (1994a, b) and Broda and Weinstein (2006), we treat \(\varepsilon _{gc,t}\) as an unobserved random variable, reflecting changes in the taste or quality of product variables. Note that \(d_{gc,t}\) reflects fundamental characteristics of a particular variety and should be treated as exogenous.Footnote 16

The export supply equation relative to country l is given by:

where \(\omega _{g}\ge 0\) is the inverse supply elasticity assumed to be the same across partner countries, and \(\delta _{gc,t}\) is an error term of supply equation which is assumed to be independent of \(\varepsilon _{gc,t}\).

A nasty feature of the system of (17) and (18) is the absence of exogenous variables to identify and estimate elasticities. By rearranging (17) and (18), one can get the following system that cannot be estimated:

To get the estimates, the system of two equations is transformed into a single equation by exploiting the insight of Leamer (1981) and the independence of errors \(\varepsilon _{gc,t}\) and \(\delta _{gc,t}\).Footnote 17 This is done by multiplying both sides of the equations. After transformation, the following equation is obtained:

where

Note that the evaluation of \(\theta _{1}\) and \(\theta _{2}\) leads to inconsistent estimates as relative price and relative market share are correlated with error \(u_{gc,t}\). Broda and Weinstein (2006) argue that it is possible to obtain consistent estimates by exploiting the panel nature of data and define a set of moment conditions for each good g. If estimates of elasticities are imaginary or of the wrong sign, the grid search procedure is implemented. Broda and Weinstein (2006) also address the problem of measurement error and heteroskedasticity by adding a term inversely related to the quantity and weighting the data according to the amount of trading flows. Recent papers by Soderbery (2010, 2013), however, report that this methodology generates severely biased elasticity estimates (median elasticity of substitution is overestimated by more than 35 %). Soderbery (2010, 2013) proposes the use of a limited information maximum likelihood (LIML) estimator instead. Where estimates of elasticities are not feasible \(({\hat{\theta }}_{1}<0)\), nonlinear constrained LIML is implemented. Monte Carlo analysis performed by Soderbery (2010, 2013) demonstrates that this hybrid estimator corrects small sample biases and constrained search inefficiencies. It further shows that Feenstra’s (1994a) original method of controlling a measurement error with a constant and correcting for heteroskedasticity by the inverse of the estimated residuals performs well. We thus follow Soderbery (2010, 2013) and use a hybrid estimator, combining LIML with a constrained nonlinear LIML to estimate elasticities of substitution between varieties using the Feenstra’s (1994a, b) method.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Benkovskis, K., Wörz, J. Non-price competitiveness of exports from emerging countries. Empir Econ 51, 707–735 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-015-1015-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-015-1015-y