Abstract

We report a case of intrahepatic bile duct adenoma (BDA) detected during laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. A 70-year-old man was referred to our hospital for the treatment of gastric cancer. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed an irregular, nodular, and elevated lesion on the greater curvature side of the middle third of the stomach. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed wall thickening with homogeneous enhancement in the middle part of the stomach, and no lesions in the liver. The patient underwent laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with regional lymphadenectomy, and during the operation a small whitish nodule was observed on the lateral segment of the liver surface. The lesion was excised by partial resection of the liver for the purpose of both histological diagnosis and treatment. Pathological examination of the liver lesion revealed no structural or cellular atypia, no stromal invasion, and immunohistochemical positivity for CK7 and CK19, but negativity for p53. The final diagnosis was well-differentiated adenocarcinoma invading the gastric serosal layer without lymph node metastasis, and intrahepatic BDA measuring 0.4 × 0.3 cm. Following surgery, the patient remained symptom-free without evidence of recurrence for 5 months. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of BDA with gastric cancer. Because it is difficult to distinguish BDA from other liver tumors including metastatic cancer due to its characteristically small size and lack of specific morphological features on standard imaging, surgical resection should be considered as the most suitable approach for both accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bile duct adenoma (BDA) is a rare benign tumor of the liver derived from the bile duct epithelium and reported in 1.3% of primary liver tumors [1]. Although the pathogenesis of BDA remains unclear, it is thought to represent a reactive process originating in the intrahepatic bile duct epithelium following damage such as that from trauma or inflammation [1, 2]. In contrast, gastric cancer is a common malignant tumor listed seventh worldwide and second in Japan among the causes of cancer-related deaths [3, 4].

We herein report a case of intrahepatic BDA with gastric cancer detected during laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer.

Case report

A 70-year-old Japanese man was referred to our hospital for the treatment of gastric cancer. His past medical history revealed a coronary stent replacement for angina pectoris followed by oral administration of anticoagulant. His laboratory findings on admission were as follows: decreased red blood cell count (427 × 104/mm3; normal range 435–555 × 104/mm3), normal white blood cell count (5.4 × 103/mm3; normal range 3.3–8.6 × 103/mm3), normal C-reactive protein levels (0.01 mg/dl; normal range < 0.3 mg/dl), and levels within the normal ranges for serum tumor markers, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9, CA 125, CA 72-4, and alpha-fetoprotein.

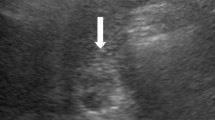

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed an irregular, nodular, elevated, lesion on the greater curvature side of the middle third of the stomach that was identified by biopsy analysis as a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed wall thickening with homogeneous enhancement in the middle part of the stomach, no enlarged lymph nodes in the perigastric area, and no liver lesions. Under a clinical diagnosis of T3N0M0 stage IIA, according to the 8th International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM classification [5], the patient underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy with regional lymphadenectomy. During surgery, we noticed a whitish, small nodule on the surface in the lateral segment of the liver (Fig. 1), suspecting the liver nodule to be a metastasis. No lesions were detected as liver metastasis from the gastric cancer by intraoperative ultrasonography. We performed distal gastrectomy with reginal lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer under laparoscopy, and then the small hepatic nodule was removed by partial resection of the lesion-containing liver segment under a small incision measuring 6 cm in diameter on the upper abdomen (Fig. 2). Because it was a small partial resection of the liver surface, we performed liver resection under direct view in the small incision.

Macroscopically, the resected specimen of liver contained a well-defined and non-encapsulated, whitish solid lesion measuring 0.4 × 0.3 cm in diameter. Histological examination revealed epithelial cell proliferation of the bile ducts and scant fibrous connective tissue stroma in the lesion (Fig. 3a). The borders between the lesion and surrounding liver tissue were distinct and no invasive growth was detected. The bile tubules in the lesion comprised well-formed, bland, cuboidal cells and duct formation without cell atypia or mitotic activity (Fig. 3b). The immunohistochemical examination showed proliferating small bile ducts positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK19, and negative for monoclonal CEA and p53, with a Ki-67 labeling index of 1% (Fig. 4). In addition, inflammatory cells which were positive for cluster of differentiation (CD)3 (Fig. 5a) and CD45 (Fig. 5b) accumulated in the hepatic lesion. Furthermore, tightly packed collagen fibers were seen in the connective tissue of the lesion by Sirius red staining (Fig. 5c) and Azan–Mallory staining (Fig. 5d). We also confirmed the diagnosis of a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma invading the gastric serosa, but with no lymph node metastasis.

Pathological results from the liver lesion. Microscopic imaging showed proliferation of the bile ducts with dense connective tissue stroma (a). Hematoxylin and eosin staining; magnification, ×10 (objective); black bar, 50 µm. The epithelial cells of the proliferated bile ducts were well differentiated with inflammation, but without obvious cell atypia or mitotic activity (b). Hematoxylin and eosin staining; magnification, ×20 (objective); black bar 50 µm

Immunohistochemical examination of the liver lesion. Immunohistochemical examination showed positive staining for cytokeratin (CK) 7 (a) and CK19 (b), but not for monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) or p53 (c). The Ki-67 labeling index was 1% (d). Magnification, ×20 (objective); black bars 50 µm

Immunohistochemical examination and connective tissue staining of the liver lesion. Immunohistochemical examination showed positive staining for cluster of differentiation (CD)3 (a), CD45 (b). Sirius red staining (c) and Azan–Mallory staining (d) show abundant fibrous component in the liver lesion. Magnification, ×20 (objective); black bars 50 µm

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and his hospitalization period was 11 days. He has been well with no evidence of recurrence for 5 months following the operation.

Discussion

We present herein a rare case of intrahepatic BDA detected in a patient with gastric cancer during laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. BDAs are an extremely rare benign tumor, usually diagnosed incidentally during a physical examination, surgery, or autopsy [6]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported BDA that was resolved during surgery for gastric cancer.

Based on an earlier histopathological study of 152 BDAs, the tumors range in size from 1 to 20 mm in diameter (mean of 5.8 mm) and are typically located immediately below the liver capsule [1]. The small size and lack of specific tumor characteristics or symptoms could account for the difficulty in locating and qualitatively diagnosing BDAs, and in our case, neither preoperative CT nor intraoperative ultrasonography detected the 0.4 × 0.3-cm liver lesion. Because the volume of liver partial resection including the lesion was small sized specimen, we did not submit it to an intraoperative histopathological consultation. Even if it was metastasis, additional resection of the liver was not carried out, because the whole lesion had been removed. Nevertheless, small-sized BDA such as the present case gives an important warning of overdiagnosis of liver nodules to surgeons in the hospitals where the intraoperative histopathological consultation is not available.

Furthermore, our case represented the so far unreported occurrence of BDA with gastric cancer. Together, these findings highlight that because the liver is a common metastatic site of gastrointestinal cancer, thorough imaging examination of the liver is important when considering the optimal therapeutic strategy for gastric cancer patients. Indeed, despite no established treatments being prescribed for liver metastasis of gastric cancer, chemotherapy is recommended for patients with unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer including liver metastases according to the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines [7]. When liver metastasis cannot be determined by imaging modalities, histopathological examination may be required to make a correct diagnosis, as highlighted in this case wherein a BDA could not be differentiated from liver metastasis during surgery.

Previous studies suggest that BDAs are usually subcapsular with a marked border without capsule, and are associated with proliferated bile ducts containing inflammatory cells [2, 6, 8]. The typical BDA pathology is positive immunohistochemical staining for CK7, CK19, and CD56, and negative staining for Ki-67 and p53 [2]. In addition, BDAs larger than 2 cm in diameter frequently show hypervascularity with prolonged enhancement on dynamic CT, MRI, or angiography, reflecting the fibrous tissues within the tumor, whereas hepatocellular carcinoma usually shows definite washout during the delayed phase of enhancement [6, 8]. In the present case, the absence of significant structural and cellular atypia or stromal invasion, and the immunohistochemical profile confirmed BDA, despite the contrast-enhanced CT not revealing the liver lesion even in the retrospective view. To ensure both an accurate diagnosis and treatment for such lesions, surgical resection is thus considered an appropriate intervention, although BDAs are defined as benign tumors.

In recent years, contra-enhanced ultrasonography using ultrasound contrast agents has been widely used in various hepatobiliary diseases, permitting the characterization of focal liver lesions due to its ability to demonstrate the vascularity of the tumor [9, 10]. Furthermore, recent advances in near-infrared fluorescence imaging using indocyanine green-enabled visualization and detection of various cancers [11, 12]. These novel imaging diagnostic techniques might be promising modalities to discriminate the malignant potential of liver tumor during the operation.

In conclusion, BDA is a rare, benign tumor that is difficult to distinguish from other liver lesions including metastatic liver tumor or hepatocellular carcinoma in spite of recent advances in imaging modalities. It is therefore important to consider BDA in the differential diagnosis of liver tumor, and further assessments by accumulation of additional cases are needed to establish an accurate diagnostic strategy, the etiological relationship between BDA and gastric cancer, and the optimal treatment.

References

Allaire GS, Rabin L, Ishak KG et al (1988) Bile duct adenoma. A study of 152 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 12:708–715

Kim SK, Kim SR, Imoto S et al (2016) Bile duct adenoma in patient with chronic hepatitis C: as a benign neoplasm by pathological and imaging studies. Pathol Int 66:640–642

Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Isobe Y et al (2013) Gastric cancer treated in 2002 in Japan: 2009 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer 16:1–27

Fidler MM, Gupta S, Soerjomataram I et al (2017) Cancer incidence and mortality among young adults aged 20–39 years worldwide in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 18:1579–1589

Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C (eds) (2017) TNM classification of malignant tumours, 8th edn. Wiley, New York

Chen L, Xu MY, Chen F (2014) Bile duct adenoma: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol 12:125

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2017) Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer 20:1–19

Albores-Saavedra J, Hoang MP, Murakata LA et al (2001) Atypical bile duct adenoma, clear cell type: a previously undescribed tumor of the liver. Am J Surg Pathol 25:956–960

D’Onofrio M, Crosara S, De Robertis R et al (2015) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of focal liver lesions. AJR 205:W56–W66

Ferraioli G, Meloni MF (2018) Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography of the liver using SonoVue. Ultrasonography 37:25–35

Namikawa T, Fujisawa K, Munekage E et al (2018) Clinical application of photodynamic medicine technology using light-emitting fluorescence imaging based on a specialized luminous source. Med Mol Morphol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00795-018-0190-2

Namikawa T, Sato T, Hanazaki K (2015) Recent advances in near-infrared fluorescence-guided imaging surgery using indocyanine green. Surg Today 45:1467–1474

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human and/or animal rights

All procedures followed have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

About this article

Cite this article

Namikawa, T., Tsuda, S., Fujisawa, K. et al. Intrahepatic bile duct adenoma in a patient with gastric cancer. Int Canc Conf J 8, 7–11 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13691-018-0345-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13691-018-0345-y