Abstract

Despite the powerful benefits of entrepreneurial failure experience with regard to experiential learning and future venture performance, our understanding of how failure experience impacts entrepreneurs’ decision to reenter entrepreneurship while taking advantage of the lessons that they have learned from their previous entrepreneurial endeavors remains limited. While some studies have highlighted the potential of entrepreneurial failure experience to stimulate reentry intention, other researchers have argued that failure experience can actually decrease subsequent entrepreneurial intention. This study draws on various streams of research on entrepreneurs’ responses to business failures at the cognitive, affective, and behavioral levels to propose the existence of a curvilinear relationship between entrepreneurial failure and reentry intention. We employ hierarchical regression to test a series of hypotheses by reference to a sample of 379 entrepreneurs who had experienced failure in their recent business ventures. The results reveal that the degree of failure exhibits an inverted U-shaped relationship with reentry intention. Furthermore, we find that the effect of entrepreneurial failure on reentry intention is mediated by entrepreneurs’ learning from failure and that entrepreneurial passion moderates the effects of entrepreneurial failure on both learning from failure and reentry intention. This article helps explain the distinctive effects of failure experience on reentry intention and provides empirical evidence that can facilitate the development of tailor-made support programs that can help previously failed entrepreneurs address the challenges that they encounter during the process of reentry into entrepreneurship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Reentry into entrepreneurship refers to the behavior exhibited by an individual who reengages in the process of new venture creation after previously experiencing entrepreneurial failure. Studies have reported that nearly 20% of entrepreneurs have past entrepreneurial experience (Plehn-Dujowich, 2010; Vaillant et al., 2024). Due to the high rate of new venture failure in most economies (Artinger & Powell, 2016; Brüderl et al., 1992; Yang & Aldrich, 2012), the contributions of entrepreneurs who have experienced prior business failures to entrepreneurial activity are significant, thus leading increasing numbers of researchers to consider the process of entrepreneurial reentry after failure (Costa et al., 2023).

Ample evidence has been provided to support the powerful benefits of entrepreneurial failure experiences with respect to experiential learning and new venture performance among individuals who restart new ventures after experiencing failure, including higher-level learning outcomes such as transformative learning, double-loop learning, and generative learning (Cope, 2011; Politis, 2005), enriched cognitive patterns that can enhance entrepreneurs’ opportunity identification ability (Espinoza-Benavides & Díaz, 2019; Lafuente et al., 2019; Ucbasaran et al., 2009), entrepreneurial dynamic capability and strategic decision comprehensiveness (Shirshitskaia et al., 2021), and new venture growth (Sarasvathy et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2022).

Notably, Vaillant et al. (2024) identified the negative effect of the time interval between entrepreneurial exit and reentry on the learning benefits of past entrepreneurial experience (i.e., the forgetting curve) with respect to serial entrepreneurs’ subsequent performance and suggested that rapid reentry into entrepreneurship should be encouraged among ex-entrepreneurs with the goal of enabling them to take advantage of the lessons they have learned from their prior entrepreneurial experience most effectively. However, in response to the multiple negative consequences of unsuccessful business ventures, including financial and social capital losses, psychological and emotional suffering, impaired physical health (De Sordi et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2007; Ucbasaran et al., 2013), harsh evaluations (Shepherd & Patzelt, 2015) and social stigmatization (Rawal et al., 2023; Singh et al., 2015), the process of reentering entrepreneurship is usually challenging for failed entrepreneurs (Hsu et al., 2017; Saylors et al., 2023; Shore et al., 2023; Simmons et al., 2014, 2019).

Despite the positive impacts of entrepreneurial failure experience on future business ventures, the tendencies and decisions of failed entrepreneurs to reenter entrepreneurship remain poorly understood, as studies on this topic have not only been remarkably scarce but also expressed opposing views. While several studies have highlighted the potential of entrepreneurial failure experience to trigger an individual’s intention to engage in new entrepreneurial ventures in pursuit of success in subsequent business activities (Rawal et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2020; Yamakawa et al., 2015), other studies have argued that entrepreneurial failure experience can actually decrease reentry intention due to the associated financial, psychological, and social costs (Lin & Wang, 2019; Singh et al., 2007; Ucbasaran et al., 2013). Moreover, empirical examinations of the relationship between entrepreneurial failure experience and reentry into entrepreneurship remain largely lacking, and most relevant studies have provided only indirect arguments or anecdotal evidence in this regard. In light of the significant benefits of past failure experience with respect to entrepreneurial activity, we must urgently obtain a deep understanding of the process of entrepreneurial reentry following entrepreneurial failure.

Therefore, our study aims to investigate how and under what conditions prior entrepreneurial failure stimulates an individual’s reentry intention. Specifically, by investigating the emotional and cognitive levels of individuals’ responses to entrepreneurial failure, we explicitly explore how the degree of such failure influences the decision to reenter new ventures through the mediation of learning from failure; we also identify entrepreneurial passion as an important contingency factor that shapes the extent to which the entrepreneur may capitalize on prior failures through experiential learning. In so doing, this study makes meaningful contributions to the extant literature on entrepreneurial failure, reentry into entrepreneurship, and learning from failure.

First, we advance our understanding of past entrepreneurial failure experience as an important antecedent of an individual’s entrepreneurial intention by providing an extensive analysis of how the degree of entrepreneurial failure is likely to influence entrepreneurs’ reentry decisions through two psychological processes that are crucial for efforts to cope with entrepreneurial failure (Smollan & Singh, 2024), namely, the emotional process (including the negative emotions evoked by failure and affective activation) and the cognitive process (including the attribution of the cause of failure and the appraisal of failure). We suggest that the degree of failure associated with entrepreneurs’ previous business ventures enhances their intention to resume such ventures after having failed, as their previous experiences may have elicited negative emotions such as anger and disappointment, thereby stimulating their desire to reenter the entrepreneurial field while making various adjustments in pursuit of future success (He et al., 2018; Shore et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2020). However, we argue that the positive effects of the degree of failure effects on reentry intention decrease and ultimately become negative effects at high levels of the degree of failure, which may cause previously failed entrepreneurs to become overwhelmed by the loss and harm appraisals associated with such severe failure (Jenkins et al., 2014; Simmons et al., 2014; Ucbasaran et al., 2013) and consequently to experience difficulty in their attempts to recover from failure and restarting a new venture. By highlighting this nonlinear relationship resulting from the distinct effects of the degree of failure, our study advances our current understanding of the impacts of entrepreneurial failure experience on reentry intention by integrating, reconciling, and extending the inconsistent and even contradictory perspectives adopted by previous studies.

Second, our study reveals the mediating mechanism that links entrepreneurial failure to reentry intention by highlighting and clarifying the role of learning from failure in the decision-making process of previously failed entrepreneurs considering whether to restart a new venture, a topic that has remained largely unexplored. Learning from failure represents the ability of an entrepreneur to acquire new knowledge by reflecting on and drawing lessons from a failed business venture with the goal of identifying and exploiting opportunities; this process has been generally acknowledged as a unique and fundamental channel that connects entrepreneurial failure experience to subsequent new venture performance (Boso et al., 2019). Since effective learning from failure can increase an individual’s level of preparedness for future entrepreneurial activities (Cope, 2011), it might also trigger the intention of an entrepreneur who has experienced failure to find and expand a new venture (Zhao & Wibowo, 2021). Thus, we suggest that learning from failure has a direct and proximal relationship with the reentry intention of previously failed entrepreneurs, and we speculate that the degree of failure affects reentry intention by influencing learning from failure.

Third, our study deepens our understanding of the relationship between business failure experience and subsequent entrepreneurial intention by introducing entrepreneurial passion as an important contingency factor in this context. In the literature on entrepreneurship and persistence, contributing factors related to individual-level values, motives, personality, and identity have been used to explain why entrepreneurs restart new ventures after experiencing entrepreneurial failure and how they respond to entrepreneurial failure at the emotional, cognitive and behavioral levels (Smollan & Singh, 2024). Entrepreneurial passion represents a powerful motivating force that can help explain the formation of individuals’ entrepreneurial intention (Karimi, 2020) and actual entrepreneurial behavior (Murnieks et al., 2014); such passion has also been reported to be associated with several decisions and endeavors associated with new business ventures, such as entrepreneurial persistence (Cardon & Kirk, 2015; Kiani et al., 2023), grit (Mueller et al., 2017) and resilience (Fisher et al., 2018), as well as with venture performance and success (Fisher et al., 2018; Mueller et al., 2017). More importantly, evidence has revealed that entrepreneurial passion has a regulatory function with regard to entrepreneurs’ negative affective experiences due to, for instance, fear of failure (Stroe et al., 2020). Accordingly, we argue that the impact of the degree of failure on reentry intention is likely to differ to some extent between highly passionate entrepreneurs and less passionate entrepreneurs.

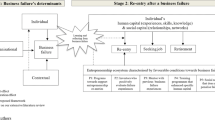

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In the subsequent section, we provide a brief literature review to elaborate the theoretical background of our conceptual framework, which is followed by a section that explains our hypothesis development. Next, the methodology section presents an overview of the empirical data and measures on which this research relies. We then demonstrate the results of this research, after which we discuss its theoretical contributions, practical implications, and limitations as well as directions for future research. Finally, a conclusion is presented. Figure 1 is a flow chart that illustrates the steps involved in this study.

Theoretical background

From failure to reentry

Due to the diversity of criteria for and manifestations of entrepreneurial failure, no clear and unified definition of entrepreneurial failure has yet been developed. Early studies on this topic equated entrepreneurial failure with the termination of business ownership. Subsequently, in light of the existence of voluntary exits or successful sales by entrepreneurs seeking to spend more time with their families or maximize their personal wealth, various scholars narrowed the scope of entrepreneurial failure to focus on cases involving bankruptcy or insolvency (Jenkins & McKelvie, 2016; McGrath, 1999). This objective definition focuses on the financial aspects of the firm. As the focus of entrepreneurial failure research has gradually shifted to the individual entrepreneur, some scholars have defined entrepreneurial failure in terms of the subjective deviation of the firm’s realistic performance from the entrepreneur’s expected goals. Entrepreneurial goals, which are determined subjectively by entrepreneurs, are multidimensional and involve various aspects, such as financial performance, business models, social relationships, personal achievement and emotions. Accordingly, maintaining operations at a level below the expected goals (as opposed to a complete exit or termination of business operations) is also considered to constitute a form of entrepreneurial failure (Jenkins & McKelvie, 2016). Based on a combination of the different perspectives mentioned above, He et al. (2018) clearly defined the category of entrepreneurial failure by combining two judgment criteria, namely, whether the business terminates its operations and whether the entrepreneurial goals are achieved. We follow this definition of entrepreneurial failure, which focuses on the pain, frustration, or trauma that the experience of entrepreneurial failure may be essential for entrepreneurs given that the aim of this research is to explore the impacts of emotional and cognitive responses to entrepreneurial failure on subsequent entrepreneurial behavior (Singh et al., 2015).

With regard to the impact of prior failure experiences on entrepreneurs’ subsequent entrepreneurial intentions, studies that have been conducted from different theoretical perspectives have reported contradictory findings. From the cognitive perspective, entrepreneurial failure is viewed as a component of trial and error that serves as an important source of information that can help entrepreneurs reflect on entrepreneurship, improve their entrepreneurial knowledge and skills, avoid making the same mistakes repeatedly, and increase the likelihood of success in the future, thereby stimulating the intention of failed entrepreneurs to restart a new business (Aguzzoli et al., 2021; Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2022; Cope, 2011). From the emotional perspective, failure experience is viewed as a critical event in entrepreneurs’ lives that triggers negative emotional experiences such as disappointment and grief, reduces entrepreneurs’ self-efficacy, and may cause entrepreneurs to lose the courage necessary to reenter entrepreneurship (Shore et al., 2023; Ucbasaran et al., 2013). Accordingly, this study explores the complex, nonlinear relationship between failure experience and reentry intentions by combining different theoretical perspectives.

Learning from failure

Learning from failure is considered to be a fundamental process through which entrepreneurs transition from failure to success (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2018, 2022), and this notion has been a vital aspect of the extant literature on entrepreneurial failure (Costa et al., 2023; Singh et al., 2007). According to experiential learning theory, intermittent experiences during the entrepreneurial journey play significant roles in entrepreneurial learning, in which context failure represents a particularly noteworthy “event” that signals problems, encourages reflection, and provides valuable practical information (Cope, 2011). Scholars have widely acknowledged the fact that learning from failure has positive effects on entrepreneurs, such as expanding their knowledge base (Shepherd, 2003) and regulating their cognitive and emotional responses (Politis & Gabrielsson, 2009), ultimately contributing to subsequent entrepreneurial success. However, scholars have also noted that multiple or costly experiences of entrepreneurial failure can impede learning from failure and that only moderate levels of failure can optimize the positive effects of experiential learning (Cardon et al., 2011). The empirical findings of Yamakawa et al. (2015) are in line with this perspective, indicating that entrepreneurs who experience a moderate number of failures are associated with optimal business creation performance. Based on these considerations, we propose that learning from failure plays a crucial mediating role in the nonlinear relationship between failure experiences and the intention to reenter entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurial passion

While scholars have provided rich insights into how entrepreneurial failure experiences affect reentry intention, the boundary conditions that shape the relationship between these two factors have not been fully investigated. The impact of entrepreneurial failure on the intention to reenter entrepreneurship is not consistently the same, and it may be influenced by the unique characteristics and motivations of individual entrepreneurs. In this regard, we aim to investigate the moderating role of entrepreneurial passion, as an inherent entrepreneurial trait, in the effects of entrepreneurial failure. Entrepreneurial passion, a distinctive quality of entrepreneurs, includes two components: identity perception and positive emotions. These aspects are expressed through experiences of conscious, intense, and positive emotions during meaningful entrepreneurial engagements in line with the individual’s entrepreneurial identity (Cardon et al., 2009). In terms of identity perception, entrepreneurs are commonly persistent in their pursuit of goals with the goal of safeguarding their identity (Drnovsek et al., 2016). With regard to positive emotions, entrepreneurial passion serves as a unique emotional state that promotes motivation and untapped potential, thus enabling entrepreneurs to overcome daunting challenges (Biraglia & Kadile, 2017). Thus, entrepreneurial passion may moderate relationship between entrepreneurial failure experiences and reentry intentions by weakening and/or strengthening individuals’ emotional and cognitive responses to entrepreneurial failure.

Hypothesis development

The degree of failure and reentry

Previous research on the intention of failed entrepreneurs to reenter entrepreneurship has focused primarily on the influence of past entrepreneurial failure experience on their likelihood of initiating new ventures (Lafuente et al., 2019). Moreover, although some studies have examined entrepreneurial failure experience in terms of the number of past failures (Hwang & Choi, 2021), only limited attention has been given to the severity or magnitude of the losses associated with entrepreneurial failure (Eftekhari & Timmermans, 2022; Lin & Wang, 2019). The present study focuses on the economic, psychological, and social costs of individuals’ most recent experience of entrepreneurial failure. Such losses include reduced personal income, increased debt burden, impaired family relationships, and decreased social status (Ucbasaran et al., 2013). Rather than focusing solely on whether individuals have experienced entrepreneurial failure, we use the degree of such failure to investigate the nonlinear relationship between failure experience and the intention to reenter entrepreneurship.

Additionally, the impact of entrepreneurs’ most recent entrepreneurial failure experience on their emotional cognitive responses and behavioral tendencies is more direct and pronounced than that of the cumulative number of previous entrepreneurial failures (Ucbasaran et al., 2013). Furthermore, variations in the extent of entrepreneurial failure give rise to distinct emotional and cognitive response patterns among entrepreneurs (Walsh & Cunningham, 2017; Williams et al., 2020; Yamakawa & Cardon, 2015). However, the literature has focused primarily on the linear influence of entrepreneurial failure experience on the intention to reenter entrepreneurship. In contrast, we assess entrepreneurial failure in a more nuanced manner by taking different degrees of failure into account. By so doing, we provide a more comprehensive explanation of the intricate, nonlinear relationship between entrepreneurial failure experience and reentry intention, thereby generating deeper insights into the notions of entrepreneurial failure and reentry.

Based on the conceptualization of serial entrepreneurial intentions proposed by Souitaris et al. (2007), we define reentry intention in terms of the psychological tendency or likelihood of entrepreneurs who have experienced entrepreneurial failure to reengage in entrepreneurial activities. We draw on research pertaining to entrepreneurial failure to analyze the emotional and cognitive effects of entrepreneurial failure, thereby proposing a nonlinear relationship between the degree of entrepreneurial failure and the intention to reenter entrepreneurship. That is, as the degree of entrepreneurial failure increases, the intention to reenter entrepreneurship initially increases. However, after reaching a turning point, further increases in the degree of entrepreneurial failure may lead to decreases in the intention to reenter the process of venture creation.

Specifically, according to He et al. (2018), emotions play a crucial role in motivating individuals, and the activation of different emotions can lead to the emergence of distinct behavioral motivations. Furthermore, the intensity of behavioral motivation is influenced by the degree to which a specific emotion is triggered. When entrepreneurs experience low levels of failure, they typically experience negative emotions such as anger and disappointment. These negative emotions stimulate entrepreneurs’ desire to bridge the gap between reality and expectations (Shepherd, 2003), thus motivating them to seek feedback from their failures, make adjustments, and reengage in entrepreneurial activities in pursuit of future success; in turn, this process enhances their intention to restart a new venture. Furthermore, within a certain range of degrees of failure, entrepreneurs’ aforementioned emotional arousal is amplified, resulting in an increase in their intention to reenter entrepreneurship.

From a cognitive perspective, a marginal failure may induce a near-miss effect, thus suggesting that experiences of failure at a point close to success can encourage additional attempts (Fan-Osuala, 2021). In cases of such marginal failure, entrepreneurs perceive their unsuccessful entrepreneurial endeavors as unfulfilled but potentially attainable goals that can be achieved in the future. This positive perception sustains and enhances their self-efficacy and sense of control, following which it prompts them to adopt a more positive mindset regarding their ability to change their circumstances. Consequently, failed entrepreneurs can obtain a comprehensive understanding of the challenges associated with entrepreneurship, recognize their own limitations, and identify the skills and qualities that are necessary for success in this context. Based on their hard work, they come to expect entrepreneurial success in the future, thus increasing their motivation to embark on a new venture.

However, when the level of failure exceeds a certain threshold, it triggers strong negative emotions and negative cognitive evaluations, which can impede the formation of reentry intention on the part of failed entrepreneurs. In the specific context of emotions, as the level of failure increases, entrepreneurs experience intense negative emotions such as sadness, shame, and self-blame (Ucbasaran et al., 2013), which can significantly decrease their motivation to initiate a new venture. Additionally, due to the societal stigma associated with failure, entrepreneurs may perceive a considerable degree of temporal and psychological distance between themselves and entrepreneurial success, thus decreasing their confidence in their ability to make a comeback (Simmons et al., 2014). Furthermore, in response to the high social costs of failure, a major setback might cause entrepreneurs to experience fear of failure, which can decrease their willingness to try again and inhibit their growth aspirations (Henriquez-Daza et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2021).

Cognitively, severe entrepreneurial failures are usually appraised as forms of harm and loss (rather than as challenges) in terms of financial income, independence, and self-esteem (Jenkins et al., 2014). As Lin and Wang (2019) reported, the greater the loss associated with failure is, the longer a previously failed entrepreneur requires to restart a business venture. Furthermore, such a large failure is likely to cause entrepreneurs to fall into a failure trap and to develop regurgitated patterns of thinking (Seckler et al., 2017), which can increase their frustration and grief while decreasing their self-efficacy and risk propensity (Shepherd et al., 2009; Yamakawa et al., 2015); such a failure can also decrease entrepreneurs’ optimism in the context of subsequent business ventures (Ucbasaran et al., 2010), which may therefore weaken their subsequent entrepreneurial intention. Empirical evidence has shown that an entrepreneur whose new venture is underperforming is likely to experience regret regarding the choice of this career instead of a regular job (Hsu et al., 2019), which may in turn drive the entrepreneur in question to exit the entrepreneurial career as a way of reducing such regret (Kawai et al., 2023).

In summary, different degrees of failure entail differences in the extent to which such failures influence the intention to reenter entrepreneurship. That is, when the level of failure is within a certain threshold, the degree of failure positively affects the individual’s intention to start a new business, but when the level of failure exceeds a certain threshold, the degree of failure negatively affects the individual’s intention to start a new business. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

-

H1: The relationship between the degree of entrepreneurial failure and reentry intention is an inverted U-shaped relationship.

The mediating role of learning from failure

We have discussed the different emotional and cognitive responses that are triggered by different levels of entrepreneurial failure and their nonlinear effects on the intention to reenter venture creation after failure. However, it is also necessary to explore the evolving effects of the emotions and cognitions associated with entrepreneurial failure on the inclination to start a new business. We aim to fill this research gap by identifying learning from failure as an essential intermediate mechanism that underlies the relationship between these two factors. Similarly, failure experience does not have a simple linear effect on learning from failure; rather, it is influenced by the emotional and cognitive effects of different levels of entrepreneurial failure.

Learning from failure is considered to be a type of future-oriented learning that helps prepare previously failed entrepreneurs for subsequent entrepreneurial success by improving their abilities in terms of opportunity exploration and exploitation (Cope, 2011). Learning from failure does not occur automatically and, to a large extent, depends on how entrepreneurs respond to failure at the emotional and cognitive levels since it often requires them to overcome various emotional and cognitive obstacles to reflect effectively on their failed business activities and to learn valuable lessons therefrom (Lattacher & Wdowiak, 2020).

When failure is at a low level, entrepreneurs are more capable of accepting and digesting the negative emotions associated with failure. They maintain their composure, actively seek and process information related to the failure event, and adopt a positive approach by focusing on potential opportunities in contexts involving adversity (Byrne & Shepherd, 2015). From a cognitive perspective, a moderate failure can trigger individuals’ need to learn and fuel the process of experiential learning with the aim of promoting future success (Hurmerinta et al., 2024). Entrepreneurs who employ constructive cognitive strategies tend to attribute failure to internal sources, engage in self-reflection and effectively process information feedback regarding failure events (Walsh & Cunningham, 2017; Yamakawa & Cardon, 2015).

However, when failure exceeds a certain threshold, entrepreneurs become deeply immersed in the losses and harm caused by the stressful situation. The ensuing intense negative emotions lead to self-doubt and self-denial, which overwhelm entrepreneurs and deplete their cognitive resources. Consequently, their ability to process information is impaired (Shepherd, 2003). This situation also impairs their attentiveness to external information and knowledge, thus preventing them from engaging in behaviors related to learning from failure (Cope, 2011; Shepherd et al., 2009). Furthermore, a large failure may encourage self-serving attribution bias. In this context, entrepreneurs who deny their personal responsibility for failure do not learn from their mistakes (Mantere et al., 2013), disregard information feedback from the failure event and face challenges in their efforts to scan and obtain information effectively (Yamakawa & Cardon, 2015). We thus propose the following hypothesis:

-

H2: The relationship between the degree of entrepreneurial failure and learning from failure is an inverted U-shaped relationship.

Furthermore, we deduce the existence of a positive correlation between the degree of learning from failure and the intention to reenter the process of venture creation. When entrepreneurs enhance their level of learning from failure, they acquire novel knowledge, expand their entrepreneurial competencies such as those pertaining to the process of identifying and developing opportunities, augment their entrepreneurial vigilance, and consequently increase their prospects of succeeding in subsequent ventures (Cope, 2011). As a result, their intention to reenter venture creation is enhanced. Moreover, the process of learning from failure enables entrepreneurs to cultivate self-efficacy and enhance their sense of behavioral control, thereby mitigating the influence of failure bias and facilitating their recovery from setbacks (Cope, 2011). This situation leads to the emergence of a behavioral inclination toward the initiation of new business ventures (Yamakawa et al., 2015). Namely, as the entrepreneur’s level of learning from failure increases, the potential augmentation of this individual’s entrepreneurial knowledge and skills and the corresponding development of self-efficacy collectively contribute to entrepreneurs’ intention to reenter venture creation. Studies have provided evidence indicating that learning from failure can promote entrepreneurial resilience through knowledge creation (Yao et al., 2021). Entrepreneurial resilience, which helps individuals cope with setbacks, in turn plays a crucial role in reentry into entrepreneurship after failure (Corner et al., 2017). Furthermore, Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue (2019) reported that after business closures, entrepreneurs who have accumulated broader and deeper experiential capital (i.e., those who have acquired skills pertaining to business opportunity identification and exploitation from previous organizations) are more likely to reenter entrepreneurship more quickly. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

-

H3: Learning from failure is positively related to reentry intention.

Therefore, we examine the mediating role of learning from failure in the relationship between entrepreneurial failure and the intention to reenter entrepreneurship. Failure experiences serve as vital opportunities to engage in entrepreneurial learning, in which context the extent of failure has a nonlinear impact on learning from failure due to variations in emotional and cognitive responses. This factor, in turn, positively affects the intention to reengage in entrepreneurial activities.

As the level of failure increases up to a certain point, negative emotions such as anger and disappointment are elicited, thus motivating entrepreneurs to learn from their failures and improve their entrepreneurial skills. This process leads them to reenter venture creation, achieve success, and enhance their sense of entrepreneurial efficacy and control (He et al., 2018). Simultaneously, in the cognitive context, entrepreneurs tend to interpret failure events optimistically and to view failure as a catalyst for continuous growth and the pursuit of challenging entrepreneurial endeavors (Walsh & Cunningham, 2017; Williams et al., 2020). In addition, as Politis and Gabrielsson (2009) suggested, entrepreneurs who have more extensive experience with critical setbacks during the new venture creation process, as well as business closures, are likely to exhibit more favorable attitudes toward failure due to the valuable lessons they have learned.

However, when failure exceeds a certain level, entrepreneurs experience intense negative emotions such as grief and shame, which reduce their autonomy and motivation. These emotional experiences, alongside persistent negative thinking patterns, hinder entrepreneurs’ ability to reflect on and learn from their failures effectively (Shepherd, 2003). As a result, their intention to reenter venture creation is lower. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

H4: Learning from failure plays a mediating role in the relationship between the degree of entrepreneurial failure and reentry intention.

The moderating role of entrepreneurial passion

The preceding analysis highlighted the fact that emotional and cognitive responses to entrepreneurial failure have both favorable and adverse outcomes. The positive effects of these factors are due primarily to the revival of intrinsic motivation and a constructive interpretation of failure incidents. Conversely, the negative consequences include increased stress and a sense of resource depletion. This study suggests that entrepreneurial passion amplifies the positive impacts of emotional and cognitive responses to failure experiences while mitigating their negative repercussions with respect to learning from failure and reentry intention.

On the one hand, entrepreneurial passion enhances the positive effects of entrepreneurial failure emotions and cognitive stigma when the level of failure in question is low. Entrepreneurial passion, which is a kind of positive emotion, can strengthen entrepreneurs’ internal drive, enhance the degree to which intrinsic motivation is elicited (Cardon & Kirk, 2015), drive entrepreneurs to actively reinvest their resources and energy in entrepreneurial activities, and enhance their intention to reenter venture creation. Moreover, a strong and positive emotional experience can effectively mitigate the fear of entrepreneurial failure, encourage entrepreneurs to engage in challenging cognitive evaluations of their failure experiences, enable them to cope with the current stressful situation in a positive manner, and facilitate learning from failure (Baum & Locke, 2004). In addition, entrepreneurial passion reflects a strong identity on the part of entrepreneurs, particularly an identity that is characterized by perceptions such as “I am an entrepreneur” and “I want to be an entrepreneur” (Cardon et al., 2009); in turn, such perceptions help increase entrepreneurs’ risk-taking tendencies and entrepreneurial commitment (Drnovsek et al., 2016), thus motivating them to learn from entrepreneurial failures and to continue to engage in entrepreneurial activities despite their experiences of entrepreneurial failure.

Studies on this topic have reported that affective and cognitive well-being have important regulatory functions, such as with regard to facilitating recovery in the exhaustion-exit (the flip side of persistence) process (Shahid & Kundi, 2022), and that personal initiative can enhance the behavioral tendency of individuals to learn from failure (Wang et al., 2022). Furthermore, a longitudinal analysis conducted by Belchior and Castro-Silva (2023) indicated that the temporal stability and path dependence of the positive effect of entrepreneurial identity aspiration on entrepreneurial behavior, even in the context of unsuccessful experiences, does not lead to decreased salience. More importantly, an individual who exhibits a high level of entrepreneurial passion is likely to be motivated to devote considerable effort to the task of exploring business opportunities (Tu et al., 2023). Accordingly, due to the significant role played by entrepreneurial passion, we treat it as an important positive force that can encourage previously failed entrepreneurs to restart new businesses.

On the other hand, entrepreneurial passion mitigates the negative effects of entrepreneurial failure emotions and cognitive stigma when the level of failure exceeds a certain level. Entrepreneurial passion can help entrepreneurs develop their own psychological resources, enable them to recover from stressful environments (Newman et al., 2021), reduce their rumination and excessive focus on negative emotions, and encourage them to address failure events in a more objective manner. Moreover, due to the motivation associated with identity, entrepreneurs who exhibit high levels of entrepreneurial passion actively take measures to consolidate their entrepreneurial identity (Cardon & Kirk, 2015); in situations involving entrepreneurial failure, this process leads them to avoid emotional and cognitive disturbances, learn from failure positively and effectively, improve their self-efficacy and behavioral control, and develop the intention to reenter the entrepreneurial world. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

-

H5a: Entrepreneurial passion strengthens the inverted U-shaped relationship between the level of entrepreneurial failure and reentry intention. As the level of entrepreneurial passion increases, the inverted U-shaped curve associated with the effect of the degree of entrepreneurial failure on reentry intention becomes steeper, and the inflection point shifts toward the right.

-

H5b: Entrepreneurial passion strengthens the inverted U-shaped relationship between entrepreneurial failure and learning from failure. As the level of entrepreneurial passion increases, the inverted U-shaped curve associated with the effect of entrepreneurial failure on learning from failure becomes steeper, and the inflection point shifts toward the right.

In addition to its moderating roles in the inverted U-shaped relationships between the level of entrepreneurial failure and both learning from failure and the intention to restart a business, entrepreneurial passion may also strengthen the positive relationship between learning from failure and the intention to restart a business. On the one hand, the positive emotions associated with higher levels of entrepreneurial passion can absorb the possible negative impacts of learning from failure to some extent, including the negative emotions pertaining to loss or frustration that occur due to reflective learning about one’s own capabilities or the limitations of external environments; in turn, this process can help entrepreneurs maintain their self-efficacy and focus their attention on the tasks of identifying and exploiting new entrepreneurial opportunities. On the other hand, at a given level of learning from failure, as the degree of entrepreneurial passion increases, identity-driven self-validation motives are enhanced, thus leading entrepreneurs to utilize learning from failure proactively to reengage in entrepreneurial activities in an attempt to preserve and consolidate their entrepreneurial identities by seeking future success. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

-

H5c: Entrepreneurial passion strengthens the positive relationship between learning from failure and reentry intention. As the level of entrepreneurial passion increases, the positive effect of learning from failure on reentry intention becomes more significant.

The theoretical model on which this study relies is shown in Fig. 2.

Methodology

Research procedure and sample

As the focus of our research is on the impact of entrepreneurial failure on reentry intention, in line with previous studies (Shore et al., 2023), a cross-sectional survey was conducted to collect sensitive data regarding entrepreneurial failure experiences from entrepreneurs. To collect such data, questionnaires were sent to target respondents (i.e., entrepreneurs who had experience in this regard) via multiple channels during three months in 2019. First, the author team visited the local business incubation center with the goal of identifying entrepreneurs and distributing well-designed survey questionnaires to them. Second, the author team distributed the questionnaire to entrepreneurs with whom they were acquainted; the authors also encouraged these entrepreneurs to share the questionnaire via WeChat and other social media platforms and to send the questionnaire to other entrepreneurs with whom they were acquainted. This approach facilitated the accumulation of questionnaire data through a process involving social fission and friend recommendations.

A total of 960 questionnaires were received and screened based on the following criteria. First, the question “Have you ever experienced entrepreneurial failure (the cessation of business operations due to failure to meet expectations, project failure, financial difficulties, etc.)?” was asked at the beginning of the questionnaire with the goal of identifying effective responses. Second, questionnaires featuring omissions, incomplete information, a single answer throughout the questionnaire, and obvious logical errors were eliminated. As a result, 379 valid questionnaires were included in this research. A total of 61.5% of the respondents were male, and most (277) were in the age range of 26–35 years. Among these respondents, 15.51% held a master’s degree or higher level of education, followed by 75.46% who held a bachelor’s degree and 7.92% who held a junior college diploma; the remaining 2.11% of respondents held a high school or technical secondary degree.

Research instrument

To ensure reliability and validity, this study used mature scales as measurement tools. Unless otherwise noted, each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Table 1 presents the items used to measure the key variables in this study.

Dependent variable

The reentry intention scale developed by Chen et al. (1998) was used to measure respondents’ intention to start a new business. This scale included 4 items, such as “I would still consider embarking on a new business venture after failing”. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the reentry intention scale was 0.874.

Independent variable

Entrepreneurial failure was measured on a 5-point Likert scale in terms of the dimensions of economic cost and psychological cost based on the research of Jenkins and McKelvie (2016); this scale included four items such as “the degree to which your most recent entrepreneurial activity impacted your personal financial situation”. Higher scores indicated higher levels of entrepreneurial failure among participants. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entrepreneurial failure scale was 0.959.

Mediator

The measure of learning from failure was adapted from Atuahene-Gima and Murray (2007) and consisted of 10 items, including “I searched for information to refine common methods and ideas for solving problems”. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the learning from failure scale was 0.959.

Moderator

Entrepreneurial passion was assessed using the scale developed by Cardon et al. (2013), which included the two subdimensions of positive emotions and identity. This scale included 13 items, such as “Establishing a new company excites me”. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entrepreneurial passion scale was 0.940.

Control variables

In line with previous studies (Cardon et al., 2013; Mueller & Shepherd, 2016), we also controlled for entrepreneurs’ gender, age, and level of education. Gender was dummy-coded as a categorical variable (0 = male, 1 = female), and age was coded as a categorical variable (1 = 21–25 years old, 2 = 26–30 years old, 3 = 31–35 years old, 4 = 36–40 years old, 5 = 41–45 years old). We also dummy-coded the extent of education as a categorical variable (1 = high school/technical secondary degree or below, 2 = junior college diploma, 3 = bachelor’s degree, 4 = master’s degree, 5 = PhD or above), which was used to capture the participant’s highest level of education.

The variance inflation factors (VIFs) exhibited by the control variables and independent variables were < 2.5, with a maximum of 2.14, i.e., below the recommended threshold of 10. These values indicate that multicollinearity was not a significant concern in this research. To mitigate common method bias, we incorporated several strategies into the survey design. These strategies included separating the dependent and independent variables, including reversed questions, and explicitly indicating that the survey was anonymous and that the responses would be used for academic research. According to Harman’s single-factor test, the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) revealed that the first component explained 41.501% of the total variance (i.e., less than the 50% threshold).

As mentioned, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for each variable exceeded 0.85, thus indicating that the scales exhibited good internal consistency. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test the discriminant validity of the main variables, namely, entrepreneurial failure (EF), learning from failure (EL), entrepreneurial passion (EP) and reentry intention (RI). As shown in Table 2, the analysis revealed that the fit indices of the hypothesized four-factor measurement models (X²/df = 3.544; CFI = 0.881; TLI = 0.870; RMSEA = 0.081; SRMR = 0.064) were better than those of the other competing models, thus indicating that the main variables included in this study exhibited good discriminant validity.

Results

The descriptive statistics and pairwise correlations among the variables are presented in Table 3. These findings reveal no significant correlations between entrepreneurial failure and learning from failure (r = 0.072, p > 0.1) or reentry intention (r=-0.020, p > 0.1), thus providing initial support for the inverted U-shaped relationship proposed in this study.

We used hierarchical regression analysis to test our hypotheses. According to Haans et al. (2016), an inverted U-shaped relationship is indicated if three conditions are met: (1) the coefficient of the squared term is significantly negative; (2) when the independent variable takes the minimum (maximum) value, the slope of the curve is significantly positive (negative); and (3) the inflection point of the curve must fall within the interval of the sample value of the independent variable.

Table 4 reports the results of the regression analysis conducted to investigate Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4. As shown in Model 2, the coefficient of entrepreneurial failure is significantly positive (α1 = 2.276, p > 0.1), and the coefficient of its squared term is significantly negative (α2=-0.375, p < 0.01). When entrepreneurial failure takes the minimum value of 1, the slope is α1 + 2α2*EFmin=1.526 > 0; in contrast, when it takes the maximum value of 5, the slope is α1 + 2α2*EFmax=-1.474 < 0. The value of entrepreneurial failure at the inflection point of the curve is -α1/2α2 = 3.035, which is within the interval of the sample value. In summary, as entrepreneurial failure increases, reentry intention tends first to increase and then to decrease. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

The results of Model 3 reveal that the coefficient of entrepreneurial failure is significantly positive (β1 = 2.976, p > 0.1), and the coefficient of its squared term is significantly negative (β2=-0.479, p < 0.01). When entrepreneurial failure takes the minimum value of 1, the slope is β1 + 2β2*EFmin=2.018 > 0; in contrast, when it takes the maximum value of 5, the slope is β1 + 2β2*EFmin=2.018 > 0. The value of entrepreneurial failure at the inflection point of the curve is β1 + 2β2*EFmin=2.018 > 0, which is within the interval of the sample value. Therefore, as entrepreneurial failure increases, learning from failure tends first to increase and then to decrease. Accordingly, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

In addition, this study used the stepwise regression method (Baron & Kenny, 1986) to test the mediating role of learning from failure in this context. As shown in Model 4 of Table 4, the relationship between learning from failure and reentry intention is significant and positive (γ1 = 0.776, p < 0.01), thus confirming Hypothesis 3. Model 5 reveals that the coefficient of entrepreneurial failure (δ1=-0.048, p > 0.1) and the coefficient of its squared term (δ2=-0.001, p > 0.1) are not significant, while the coefficient of learning from failure (δ3 = 0.781, p < 0.01) is significantly positive. Overall, after the addition of learning from failure to the regression model of the effect of entrepreneurial failure on reentry intention, the direct effect of entrepreneurial failure on reentry intention is no longer significant. Accordingly, learning from failure mediates the inverted U-shaped relationship between entrepreneurial failure and reentry intention. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

The regression findings regarding the moderating effect are presented in Table 5. As shown in Model 6, the coefficient of the interaction term between entrepreneurial failure and entrepreneurial passion is not significant (ε4 = 0.009, p > 0.1), while the coefficient of the interaction term between the squared term of entrepreneurial failure and entrepreneurial passion is negative and significant (ε5=-0.221, p < 0.01). Furthermore, as Fig. 3 indicates, when the level of entrepreneurial passion increases, the inflection point of the inverted U-shaped curve that characterizes the relationship between entrepreneurial failure and reentry intention shifts toward the right and tends to become steeper. Therefore, Hypothesis 5a is supported. Similarly, Model 7 reveals that the coefficient of the interaction term between entrepreneurial failure and entrepreneurial passion is significantly positive (η4 = 0.009, p < 0.01), while the coefficient of the interaction term between the squared term of entrepreneurial failure and entrepreneurial passion is significantly negative (η5=-0.336, p < 0.01), thus providing support for Hypothesis 5b.

As shown in Model 8, the coefficient of the interaction term between learning from failure and entrepreneurial passion is positive but not significant (θ3 = 0.082, p > 0.1). Accordingly, Hypothesis 5c is not supported. A possible explanation for this finding may be that the moderating role played by entrepreneurial passion in the dynamic effect of entrepreneurial failure on reentry intention focuses on the early stage of learning from failure. The two dimensions of entrepreneurial passion, namely, positive emotion and identity, influence the effectiveness of learning from failure by strengthening the positive effects and weakening the negative effects of entrepreneurial failure, following which they indirectly affect reentry intention. Thus, the moderating effect of entrepreneurial passion on the relationship between learning from failure and reentry intention is not obvious.

Discussion

Despite the significant role played by entrepreneurial failure experience in experiential learning and future venture performance, our understanding of how failure experience impacts entrepreneurs’ intention to restart a new venture by taking advantage of the lessons they have learned from their previous entrepreneurial endeavors remains limited. The literature on this topic has suggested that entrepreneurial failure has either a positive or negative impact on reentry intention (Lafuente et al., 2019). This study draws on various streams of research to propose that entrepreneurial failure has a curvilinear effect on reentry intention; we also analyze the mediating effect of learning from failure and the moderating effect of entrepreneurial passion in this context. The results of this research reveal that entrepreneurial failure exhibits an inverted U-shaped relationship with reentry intention and that the effect of entrepreneurial failure on reentry intention is mediated by learning from failure. Moreover, entrepreneurial passion moderates the effects of entrepreneurial failure on learning from failure and reentry intention, as the inverted U-shaped relationship becomes steeper when failed entrepreneurs exhibit higher levels of entrepreneurial passion.

Theoretical contributions

First, although this research enhances our understanding of the effects of entrepreneurial failure experience on the emotional and cognitive changes experienced by entrepreneurs (Cope, 2011; Shepherd, 2003; Shepherd et al., 2009) as well as their future decisions and actions (Eggers & Song, 2015; Williams et al., 2020), the literature has been mostly silent with regard to the differential impacts of entrepreneurial failure experience in terms of its characteristics (rather than its mere presence) on the likelihood that entrepreneurs will initiate a subsequent business venture, especially in an empirical setting. The novelty of our study regarding the effect of entrepreneurial failure experience is due to our introduction of the degree of failure to this context. By focusing on the degree of failure, this study theoretically and empirically explores the nonlinear influence of entrepreneurial failure experience on reentry intention both theoretically and empirically. While previous studies have mainly analyzed the simple linear effects of entrepreneurial failure on subsequent entrepreneurial cognition, behavior and performance from a single perspective, this study integrates emotional and cognitive processing mechanisms to propose that entrepreneurial failure has a double-edged sword effect. Furthermore, the empirical results reveal that entrepreneurial failure has an inverted U-shaped effect on reentry intention. By analyzing different degrees of failure, the heterogeneous impacts of entrepreneurial failure experience on learning from failure and reentry intention are explored, thus expanding our understanding of the effects of entrepreneurial failure experience.

Second, the study investigates learning from failure as a crucial mediating mechanism in the relationship between entrepreneurial failure and reentry intention. Although previous studies have documented how entrepreneurs respond to failure at the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral levels, most such studies have investigated these levels of response only in part. Very little research has focused on how these different types of responses interact with each other, particularly over time, and little empirical testing has been performed in this regard (Smollan & Singh, 2024). The few empirical studies that have explored the relationships among these levels of response have focused on emotional and/or cognitive responses to learning in the contexts of confronting failure or generating reentry intentions after failure. Moreover, although many scholars have suggested that learning from failure can increase the intentions of previously failed entrepreneurs to restart a new business (De Hoe & Janssen, 2022), little empirical evidence has been provided in this regard. Previous theoretical and empirical studies on the consequences of entrepreneurial failure have called for new research to provide a full overview of how previous failure might affect entrepreneurs at the cognitive, affective, and behavioral levels in the process of deciding whether or not to reenter entrepreneurship (Mandl et al., 2016; Mantere et al., 2013). Our study fills this gap in the extant literature by responding to these calls. By addressing the emotional and cognitive levels of responses to entrepreneurial failure, we explicitly investigate how the degree of failure influences entrepreneurs’ decision to reenter new ventures through the mediation of learning from failure (behavioral response). Thus, our study not only opens the black box regarding the relationship between business failure experience and subsequent entrepreneurial intention but also makes a valuable contribution to the literature on the relationship between failure experience and learning from failure. Previous studies on this topic have analyzed the influence of business failure experience on learning from failure; however, they have focused mainly on the linear effects of business failure experience (Boso et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019), thereby ignoring the potential curvilinear relationship between business failure experience and learning from failure (except He et al. (2018). This oversight is surprising in light of the intricate emotional and cognitive reactions of entrepreneurs to business failure (Byrne & Shepherd, 2015). At different levels of, business failure experience might have distinctive effects on entrepreneurs’ behaviors with regard to learning from failure due to the completely different responses to business failure that occur at the cognitive and emotional levels.

Third, the study provides support for the claim that entrepreneurial passion plays a moderating role in the “entrepreneurial failure– learning from failure– reentry intention” relationship, which constitutes a significant contribution to the entrepreneurial passion literature. While many studies have connected passion to positive entrepreneurial activities, the current study is unique in that it examines entrepreneurial passion in the context of business failures both theoretically and empirically (Fu et al., 2023; Walsh & Cunningham, 2023). Our results thus contribute to the literature on entrepreneurial passion by highlighting the ability of entrepreneurial passion to modulate entrepreneurs’ emotional and cognitive responses to failure during the processes of learning from failure and reentry after failure.

Practical implications

This study has several practical implications concerning how entrepreneurs who have experienced failure can effectively restart a new venture.

First, beyond the levels of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, attributions, and public failure narratives (Baù et al., 2017; Hsu et al., 2017; Saylors et al., 2023), the findings of our study demonstrate that the extent of entrepreneurial failure has curvilinear effects on reentry intention, thus indicating that entrepreneurs may employ diverse coping strategies in response to varying degrees of entrepreneurial failure. When the degree of entrepreneurial failure is relatively low, entrepreneurs should prioritize learning from failure, actively search for clues regarding the causes of entrepreneurial failure, and develop reasonable and effective interpretations, thus enhancing their own entrepreneurial abilities and increasing the probability of future venture success. If the degree of entrepreneurial failure is high, it is necessary to take conscious steps to adjust and overcome the negative cognitions and emotions associated with the experience of failure with the goal of mitigating the corresponding interference and obstruction of learning from failure and subsequent entrepreneurial intention.

Second, our empirical findings reveal that learning from failure mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial failure and reentry intention, thereby explaining how entrepreneurial passion moderates the process of recovering from failure. As such, entrepreneurs can deal with unpleasant emotions effectively by utilizing various tactics, such as adopting an optimistic mindset and seeking assistance from others, thus enabling them to engage in entrepreneurial learning more quickly and strengthening their belief in their ability to found new businesses. This approach is expected to be particularly impactful when it is employed by passionate entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs should also pay attention to institutional change, impression management, and knowledge management when learning from their past failures (Edeh et al., 2023; Fanaja et al., 2023; Pimentel et al., 2023).

Third, in light of the critical role of learning from failure highlighted by our study, local governments, business incubators, and other relevant organizations in the entrepreneurial ecosystem can enhance the specialized counseling and other interventions they provide to entrepreneurs who have experienced business failure. On the one hand, they should establish a supportive cultural atmosphere that fosters entrepreneurship and accommodates failures, guide mainstream media outlets to report entrepreneurial activities objectively with the goals of reducing public prejudice against entrepreneurial failures and helping alleviate the psychological and social pressures faced by entrepreneurs after failures. On the other hand, they can also improve entrepreneurship education and training (Slade Shantz et al., 2024; Walter & Block, 2016), project consulting, technical guidance, etc., not only to foster specific entrepreneurial skills and professional counseling regarding industry insights to entrepreneurs but also, more importantly, to establish a conducive atmosphere, promote positive and harmonious entrepreneurial passion and improve learning efficiency.

Limitations and directions for future research

Despite the valuable conclusions of this study, it has certain limitations that could be addressed by future research. First, this study focuses on the effect of the degree of entrepreneurial failure on the intention to reenter venture creation, and future researchers can combine the number of entrepreneurial failures (Yamakawa et al., 2015) with the velocity of entrepreneurial failure (He et al., 2018), the time between failures, the reasons for entrepreneurial failures (Franco et al., 2021; Politis & Gabrielsson, 2009; Shore et al., 2023), and other characteristics of this experience to examine the effects of the interactions among these factors on the entrepreneurial decision-making of subsequent entrepreneurship in light of the differentiated impacts revealed by this research. Second, the effects of emotional and cognitive responses to failure are also shaped by external environmental conditions (Ucbasaran et al., 2013). Thus, a socialized approach that introduces social contexts to this research can be considered in the future to explore the boundary conditions associated with the relationship between failure and reentry, such as family support (Lin & Wang, 2019) and the entrepreneurial ecosystem (Simmons et al., 2014, 2019). Third, the respondents on whom this study focuses are entrepreneurs who have experienced failure, and it is difficult to obtain data regarding such individuals; therefore, this study uses cross-sectional data to explore the effect of entrepreneurial failure on reentry intention. Future studies should employ a longitudinal research design to validate the dynamic relationships among the degree of entrepreneurial failure, learning from failure, and reentry intentions explored in this study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while previous empirical studies have focused predominantly on the linear effects of experiences of entrepreneurial failure or the number of such failures on subsequent reentry intentions, we shift the focus of research on entrepreneurial failure experience to the degree of failure. By drawing on various research streams pertaining to entrepreneurs’ responses to business failures at the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral levels, this study theoretically elaborates and empirically examines the curvilinear relationship between the degree of entrepreneurial failure and the entrepreneur’s subsequent intention to restart a new venture as well as the mediating role of learning from failure and the moderating role of entrepreneurial passion in this context. By exploring the potentially intricate curvilinear relationship between entrepreneurial failure and subsequent reentry intentions, we contribute new insights and promote various synergies with respect to diverse theoretical perspectives on the notion of reentry after failure. Moreover, by deepening our understanding of the distinctive effects of failure experience on the process underlying the transition from failure to reentry, this study enables the challenges that previously failed entrepreneurs face during the process of reentry into entrepreneurship to be addressed through tailor-made support programs.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aguzzoli, R., Lengler, J., Sousa, C. M. P., & Benito, G. R. G. (2021). Here we go again: A case study on re-entering a foreign market. British Journal of Management, 32(2), 416–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12407

Amankwah-Amoah, J., Boso, N., & Antwi-Agyei, I. (2018). The effects of Business failure experience on successive entrepreneurial engagements: An evolutionary phase model. Group & Organization Management, 43(4), 648–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601116643447

Amankwah-Amoah, J., Khan, Z., Ifere, S. E., Nyuur, R. B., & Khan, H. (2022). Entrepreneurs’ learning from business failures: An emerging market perspective. British Journal of Management, 33(4), 1735–1756. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12557

Artinger, S., & Powell, T. C. (2016). Entrepreneurial failure: Statistical and psychological explanations [Article]. Strategic Management Journal, 37(6), 1047–1064. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2378

Atuahene-Gima, K., & Murray, J. Y. (2007). Exploratory and exploitative learning in new product development: A social capital perspective on new technology ventures in China. Journal of International Marketing, 15(2), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.15.2.1

Baù, M., Sieger, P., Eddleston, K. A., & Chirico, F. (2017). Fail but try again? The effects of age, gender, and multiple–owner experience on failed entrepreneurs’ reentry. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 909–941. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12233

Baron, R., & Kenny, D. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

Baum, J. R., & Locke, E. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.587

Belchior, R. F., & Castro-Silva, H. (2023). The virtuous cycle of entrepreneurial identity and experience - a longitudinal analysis. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 19(4), 1739–1770. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00898-7

Biraglia, A., & Kadile, V. (2017). The role of entrepreneurial passion and Creativity in developing entrepreneurial intentions: Insights from American homebrewers [Article]. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(1), 170–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12242

Boso, N., Adeleye, I., Donbesuur, F., & Gyensare, M. (2019). Do entrepreneurs always benefit from business failure experience? Journal of Business Research, 98, 370–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.063

Brüderl, J., Preisendörfer, P., & Ziegler, R. (1992). Survival chances of newly founded business organizations. American Sociological Review, 57(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096207

Byrne, O., & Shepherd, D. A. (2015). Different strokes for different folks: Entrepreneurial narratives of emotion, cognition, and making sense of business failure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(2), 375–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12046

Cardon, M. S., Gregoire, D. A., Stevens, C. E., & Patel, P. C. (2013). Measuring entrepreneurial passion: Conceptual foundations and scale validation. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(3), 373–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.03.003

Cardon, M. S., & Kirk, C. P. (2015). Entrepreneurial passion as mediator of the self-efficacy to persistence relationship. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 39(5), 1027–1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12089

Cardon, M. S., Stevens, C. E., & Potter, D. R. (2011). Misfortunes or mistakes? Cultural sensemaking of entrepreneurial failure. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(1), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.06.004

Cardon, M. S., Wincent, J., Singh, J., & Drnovsek, M. (2009). The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 511–532. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2009.40633190

Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? [Article]. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00029-3

Cope, J. (2011). Entrepreneurial learning from failure: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(6), 604–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.06.002

Corner, P. D., Singh, S., & Pavlovich, K. (2017). Entrepreneurial resilience and venture failure. International Small Business Journal-Researching Entrepreneurship, 35(6), 687–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242616685604

Costa, P. L., Ferreira, J. J., & de Torres, R. (2023). From entrepreneurial failure to re-entry [Article]. Journal of Business Research, 158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113699. Article 113699.

De Hoe, R., & Janssen, F. (2022). Re-creation after business failure: A conceptual model of the mediating role of psychological capital. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 842590. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.842590

De Sordi, J. O., dos Santos, A. R., de Azevedo, M. C., Jorge, C. F. B., & Hashimoto, M. (2022). Dark, down, and destructive side of entrepreneurship: Unveiling negative aspects of unsuccessful entrepreneurial action. International Journal of Management Education, 20(3), 100659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100659

Drnovsek, M., Cardon, M. S., & Patel, P. C. (2016). Direct and indirect effects of passion on growing technology ventures. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 10(2), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1213

Edeh, F. O., Zayed, N. M., Darwish, S., Nitsenko, V., Hanechko, I., & Islam, K. M. A. (2023). Impression management and employee contextual performance in service organizations (enterprises). Emerging Science Journal, 7(2), 366–384. https://doi.org/10.28991/esj-2023-07-02-05

Eftekhari, N., & Timmermans, B. (2022). New venture dissolution and the comobility of new venture teams. Small Business Economics, 59(1), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00543-z

Eggers, J. P., & Song, L. (2015). Dealing with failure: Serial entrepreneurs and the costs of changing industries between ventures [Article]. Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), 1785–1803. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0050

Espinoza-Benavides, J., & Díaz, D. (2019). The entrepreneurial profile after failure. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(8), 1634–1651. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijebr-04-2018-0242

Fanaja, R. A., Pradana, M., Eka Saputri, M., & Utami, D. G. (2023). Knowledge management as driver of women’s entrepreneurial innovativeness. Journal of Human Earth and Future, 4(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.28991/hef-2023-04-01-01

Fan-Osuala, O. (2021). All failures are not equal: Degree of failure and the launch of subsequent crowdfunding campaigns [Article]. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2021.e00260. Article e00260.

Fisher, R., Merlot, E., & Johnson, L. W. (2018). The obsessive and harmonious nature of entrepreneurial passion. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 24(1), 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-01-2017-0011

Franco, M., Haase, H., & António, D. (2021). Influence of failure factors on entrepreneurial resilience in Angolan micro, small and medium-sized enterprises [Article]. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 29(1), 240–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-07-2019-1829

Fu, H., Xiao, X. H., Ye, B. H. B., Fang, S. J., Li, Y. Q., & Wu, Y. Y. (2023). Stay passionate and carry on: Why passion exhausts and how it can be restored. Current Psychology, 42(31), 27574–27592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03889-z

Guerrero, M., & Peña-Legazkue, I. (2019). Renascence after post-mortem: The choice of accelerated repeat entrepreneurship [Article]. Small Business Economics, 52(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0015-7

Haans, R., Pieters, C., & He, Z. L. (2016). Thinking about U: Theorizing and Testing U- and inverted U-shaped relationships in strategy research. Strategic Management Journal, 37, 1177–1195. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2399

Henriquez-Daza, M. C., Capelleras, J. L., & Osorio-Tinoco, F. (2023). Does fear of failure affect entrepreneurial growth aspirations? The moderating role of institutional collectivism in emerging and developed countries [Article]. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-08-2022-0232

He, V. F., Sirén, C., Singh, S., Solomon, G., & von Krogh, G. (2018). Keep calm and carry on: Emotion regulation in entrepreneurs’ learning from failure [Article]. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 42(4), 605–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12273

Hsu, D. K., Shinnar, R. S., & Anderson, S. E. (2019). I wish I had a regular job’: An exploratory study of entrepreneurial regret [Article]. Journal of Business Research, 96, 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.006

Hsu, D. K., Wiklund, J., & Cotton, R. D. (2017). Success, failure, and entrepreneurial reentry: An experimental assessment of the veracity of self-efficacy and prospect theory [Article]. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 41(1), 19–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12166

Hurmerinta, L., Nummela, N., & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. (2024). Boosted by failure? Entrepreneurial internationalisation as a cyclical learning process. European Journal of International Management, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.1504/ejim.2024.136483

Hwang, K., & Choi, J. (2021). How do failed entrepreneurs cope with their prior failure when they seek subsequent re-entry into serial entrepreneurship? Failed entrepreneurs’ optimism and defensive pessimism and coping humor as a moderator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 7021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137021

Jenkins, A., & McKelvie, A. (2016). What is entrepreneurial failure? Implications for future research. International Small Business Journal-Researching Entrepreneurship, 34(2), 176–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615574011

Jenkins, A. S., Wiklund, J., & Brundin, E. (2014). Individual responses to firm failure: Appraisals, grief, and the influence of prior failure experience. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.10.006

Karimi, S. (2020). The role of entrepreneurial passion in the formation of students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Applied Economics, 52(3), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1645287

Kawai, N., Sibunruang, H., & Kazumi, T. (2023). Work-family conflict, entrepreneurial regret, and entrepreneurial outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic [Article]. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 19(2), 837–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00846-5

Kiani, A., Ali, A., Biraglia, A., & Wang, D. (2023). Why I persist while others leave? Investigating the path from passion to persistence in entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management, 61(6), 2818–2848. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1938097

Lafuente, E., Vaillant, Y., Vendrell-Herrero, F., & Gomes, E. (2019). Bouncing back from failure: Entrepreneurial resilience and the internationalisation of subsequent ventures created by serial entrepreneurs. Applied Psychology, 68(4), 658–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12175

Lattacher, W., & Wdowiak, M. A. (2020). Entrepreneurial learning from failure. A systematic review. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(5), 1093–1131. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2019-0085

Lee, C. K., Cottle, G. W., Simmons, S. A., & Wiklund, J. (2021). Fear not, want not: Untangling the effects of social cost of failure on high-growth entrepreneurship [Article]. Small Business Economics, 57(1), 531–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00324-0

Lin, S., & Wang, S. (2019). How does the age of serial entrepreneurs influence their re-venture speed after a business failure? [Article]. Small Business Economics, 52(3), 651–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9977-0

Liu, Y., Li, Y., Hao, X., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Narcissism and learning from entrepreneurial failure [Article]. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(3), 496–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.01.003

Mandl, C., Berger, E. S. C., & Kuckertz, A. (2016). Do you plead guilty? Exploring entrepreneurs’ sensemaking-behavior link after business failure [Article]. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 5, 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2015.12.002

Mantere, S., Aula, P., Schildt, H., & Vaara, E. (2013). Narrative attributions of entrepreneurial failure. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(4), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.12.001

McGrath, R. G. (1999). Falling forward: Real options reasoning and entrepreneurial failure. Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.1580438

Mueller, B. A., & Shepherd, D. A. (2016). Making the most of failure experiences: Exploring the relationship between business failure and the identification of business opportunities. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(3), 457–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12116

Mueller, B. A., Wolfe, M. T., & Syed, I. (2017). Passion and grit: An exploration of the pathways leading to venture success. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(3), 260–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.02.001