Abstract

We examine how failure ascriptions (how the core causal characteristics of a failure are identified) impact perceptions of learning, defined here as the ability to transfer knowledge from a failed venture to a subsequently started new venture. Our findings are consistent with prior work in that internal unstable failure ascriptions are associated with greater perceived learning, while external stable ascriptions are associated with less perceived learning. Inconsistent with prior work, however, we find that starting a new venture more quickly after failure enhances perceived learning for entrepreneurs who made internal unstable ascriptions. Further, entrepreneurs with external stable ascriptions have even less perceived learning when they abandon their previous domain in their new venture. Implications for research on failure, ascriptions, and perceived learning for future ventures are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Entrepreneurship is not only about success but also failure—failed attempts or even failed intentions to start new businesses that can be a precursor of another entrepreneurial emergence (Aldrich 1999; Eberhart et al. 2011; Learned 1999; Shane 2001). Moving past a perspective that failure is bad (McGrath 1999), scholars’ interest has shifted to how entrepreneurs can benefit and learn from failure (Cope and Cave 2008; Minniti and Bygrave 2001; Shepherd 2003; Sitkin 1992; Ucbasaran et al. 2013). This is because “failure can expand the entrepreneur’s range of potential behaviors, revise previously ineffective practices, highlight mistakes and augment skills and knowledge about the entrepreneurial process” (Cope 2011: 618). Failure can lead to positive outcomes such as learning (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995) that can be applied to subsequent ventures started by the failed entrepreneur (Sitkin 1992).

The challenge with our understanding of entrepreneurial failure is that the mechanism or process of learning from failure remains a black box (Cannon and Edmonson 2001; Jenkins 2012; Zacharakis et al. 1999). Prior failure experience does not always lead to future success (Green et al. 2003), and learning from failure does not happen automatically or instantaneously (Shepherd 2003). While models have been developed to explore learning (Cope 2005; Corbett 2005, 2007; Harrison and Leitch 2005; Minniti and Bygrave, 2001; Parker 2013), few studies have investigated how learning might be impacted by how individuals attribute or ascribe their failures (Cardon et al. 2011; Jenkins 2012; Yamakawa et al. 2013). Further, we have very little empirical data on how individuals explain or attribute the causes of events that occur (Brockner 2002; Greenberg 1990; Kelley and Michela 1980), and how such attributions impact learning that is applicable for entrepreneurs who venture again, or their actual subsequent venture performance (Parker 2013; Yamakawa et al. 2013). By addressing the call for research on individual level attributions and learning concerning entrepreneurial failure (Cardon et al. 2011; Ucbasaran et al. 2013), we add empirical data to help address some of the mystery concerning how prior failure impacts entrepreneurial learning applicable to later venturing (Jenkins et al. 2014; Yamakawa et al. 2013). This is important because until we understand this relationship, we cannot help entrepreneurs maximize the potential learning opportunities their failures afford them.

In this study, we focus on failure ascription, how the core causal characteristics of the failure are identified (Homsma et al. 2007), and argue that internal unstable ascriptions for prior failure will lead to greater learning, while external stable ascriptions for failure will lead to less learning. Scholars have previously suggested that entrepreneurs engage in critical self-reflection (Cope 2003, 2011) asking themselves “probing questions” (Marsick and Watkins 1990) in order to understand why failure occurred and how much of the venture’s demise was due to their own actions (Cope 2011). Yet, to our knowledge there have been only few quantitative studies to date (e.g., Jenkins 2012; Yamakawa et al. 2013) that directly examine whether entrepreneurs’ stated causes of failures impact their ability to learn and move on from the failure experience. Jenkins’ work (2012) represents the most comprehensive study to date of learning and reentry following firm failure, but by her own report, “does not take into account whether the entrepreneur actually reenters self-employment or the subsequent performance of the firm” (p. 193). This is important because learning is not complete until a person is able to test their new ideas in another firm context (Jenkins 2012; Shepherd 2003). Our first contribution is therefore to empirically examine the relationship between causal ascriptions for failure and perceived learning for the next venture among entrepreneurs who have reentered self-employment. Such perceptions of learning are critical because they may drive the extent of grief experienced by the entrepreneur (Jenkins 2012), motivation to try again with a new venture (Yamakawa et al. 2013), and/or the self-efficacy of the entrepreneur, which has been shown to play an important role in entrepreneurial motivation and action (Jenkins et al. 2014; Shepherd and Cardon 2009).

To help improve our understanding of this learning, we also explore two potential moderators of the failure-to-learning perceptions relationship. First, we look at how quickly an individual rebounds from a failure experience to venture again. Prior scholars have suggested that entrepreneurs who fail need time to heal and distance themselves from the failure before they can learn from the experience (Cope 2011; Shepherd 2009). Yet extended time to reflect can also be detrimental to recovery (Cope 2011), and we argue that a shorter time to start the next venture may be better for perceived learning. Second, we look at whether the entrepreneur remains in the domain in which the failure occurred or completely abandons the domain (Ford 1985; Kawakami 2007). Our second contribution thus comes from exploring the moderating influences of time to start another venture and domain abandonment in order to identify important boundary conditions linking failure ascriptions and subsequent perceptions of learning.

Below we provide background and definitions concerning entrepreneurial failure, learning, and perceptions of learning from failure, before examining the literature on causal ascriptions more closely. We develop and test hypotheses relating causal ascriptions to perceived learning with a sample of 220 Japanese entrepreneurs who started a new venture subsequent to experiencing an entrepreneurial failure. We conclude with a discussion of the results and implications of our study.

2 Literature review

2.1 Entrepreneurial failure

Failure has been defined differently in the literature, ranging from bankruptcy of a particular firm (Zacharakis et al. 1999) to “termination of an initiative that has fallen short of its goals” (McGrath 1999: 14). This latter focus in terms of economic performance that is below some threshold allows for the existence of organizations that are “permanently failing” (Meyer and Zucker 1989), “living dead” (Ruhnka et al. 1992), and “chronic failures” (van Witteloostuijn 1998), all of which are simply “unproductive” (Baumol 1990) at the individual, firm, and societal levels. We use the definition of failure provided by Cope (2011)—full exit of an entrepreneur and full closure of the venture due to poor performance. This is consistent with other research on entrepreneurial failure (e.g., Jenkins et al. 2014; Singh et al. 2007) that looks at failure as the discontinuance of a business and the simultaneous exit of the entrepreneur from the businesses.

2.2 Learning

Within the broader management literature, studies have identified several methods of learning, which in turn has allowed entrepreneurship studies to build on and to further understand how learning can occur in various ways.Footnote 1 For example, learning can occur from the acquisition of knowledge and skills (e.g., Bruce et al. 1995; Burke and Hutchins 2007), such as through educational processes such as training, and where the external environment influences the transferring of knowledge and skills gained to the tasks. Second, learning can occur by doing (Burgoyne and Hodgson 1983), where learning occurs from repetition of tasks (Costello 1996; Reuber and Fischer 1999) and through regularized and repetitive activities (Cope 2005), so that learning itself is a process involving repetition and experimentation (Minniti and Bygrave 2001). Third, learning can occur based on performance triggers (e.g., questioning and replacing faulty assumptions and outdated information following errors, mistakes, and failures) such that in order for learning to happen individuals need to think about and reflect on the experience (Jarvis 1987). Here, learning takes place through reflection as a process that brings meaning to the experience (Marsick and Watkins 1990; Rae and Carswell 2000).

In our study, we build on the specific context of entrepreneurship and focus on learning by doing and learning based on performance triggers. We look at causal ascription, in particular, failure ascriptions in terms of how the core characteristics of a failure are identified, because this can have a profound impact on perceived learning, which we define as perceptions concerning the ability to transfer knowledge from the failed venture to the new venture. In this way, perceived learning can occur from performance triggers (the failure of a venture) and also through the repetition of tasks, whereby the entrepreneur can choose to change (or not) his or her behavior, strategy, or approach for the subsequent venture and thereby experiment with a different approach, industry domain, or type of venture.

We build on prior work that has argued that disjunction and unexpected events (in our case a venture failure) provide greater stimulus for thought and reflection rather than more routinized experiences (Jarvis 1987; Marsick and Watkins 1990). A “deeper” reflection stems from more negative mistakes or crises that are instrumental in creating higher-level entrepreneurial learning (Cope 2005). We suggest that this reflection occurs through causal ascription processes.

2.3 Learning from failure

A substantial amount of prior literature has argued that entrepreneurial failures represent great potential for learning opportunities (Green et al. 2003). Studies have identified failure as an important source for the development of knowledge, skills, and capabilities that can be useful in subsequent activities (McGrath 1999; Minniti and Bygrave 2001; Sitkin 1992; Shepherd 2003). Learning from failure and recovery from failure are intertwined (Cope 2011; Jenkins 2012; Shepherd 2003). Although “the scientific understanding of the negative effects of errors is much better developed than that of the potential positive effects of errors” (Van Dyck et al. 2005: 1228) such as learning, innovation, and resilience (Sitkin 1996), it is difficult to measure the outcomes of learning from failure. Failure can increase an entrepreneur’s probabilities of success when they use failure as an instrument to learn “what works and does not work” (Cope 2011; Sarasvathy and Menon 2003). Yet such learning is not complete until a person is able to test the ideas they think they have learned (perceived learning) by applying them to a new venture (Jenkins 2012; Shepherd et al. 2009). In addition, while entrepreneurial failure can lead to learning, venture failure experience can also perpetuate entrepreneurial confidence, creating a “hubris,” which causes entrepreneurs to re-emerge and start new ventures, despite not learning much from prior failure experiences (Hayward et al. 2006; Jenkins 2012).

Based on this stream of research, we focus our theoretical and empirical inquiry on entrepreneurs who have failed and gone on to venture again, thereby having the opportunity (but not necessarily the certainty) to apply the lessons from the failure to the new venture. Given that “learning is a dynamic process and not an automatic by-product of a homogenous experience of entrepreneurship” (Sardana and Scott-Kemmis 2010: 445), we seek to understand why some entrepreneurs appear to learn more from failures than others.

2.4 Causal ascriptions of failure

Prior work has suggested that individuals’ responses to failures will vary substantially (Cardon et al. 2005; Jenkins et al. 2014; Ucbasaran et al. 2013; Yamakawa et al. 2013; Yanchus et al. 2003), and more specifically that there is heterogeneity in individual abilities to maximize learning from failures (Jenkins 2012; Sardana and Scott-Kemmis 2010; Shepherd and Cardon 2009). One stream of research has focused on how “failure can facilitate learning by encouraging the individual to conduct a postmortem to understand what led to the failure” (Ucbasaran et al. 2011: 544). Consistent with Jenkins (2012: 23), we believe that entrepreneurs’ interpretation of failure forms the basis for their learning from the experience (Boud and Walker 1990) since “it is through the sense making/interpretation of the experience that learning happens” (Rae and Carswell 2001: 154).

Social psychology theory suggests that attributions are the mechanisms through which individuals explain their own behaviors, actions of others, and events in the world (Martinko et al. 2006; Shaver et al. 2001). Causal attributions made for events such as failure impact individuals’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to failure (Douglas et al. 2008; Ford 1985), since the causes offer information about where to provide corrective action, if possible (Ford 1985), or whether to act at all (Jenkins 2012). Prior work suggests that when individuals experience a significant negative event such as a firm failure (Shepherd 2003; Singh et al. 2007), it is likely to stimulate attribution search (Cope 2011; Jenkins 2012), or reflection of the causes for the failure.

There are three primary dimensions along which causes of failure can be classified—locus of causality, stability, and controllability (Weiner 1985). Locus of causality addresses whether the failure is attributed to causes internal to the individual who failed or to causes external to the individual (Bettman and Weitz 1983; Heider 1958). Stability refers to whether the attributed causes are likely to remain fairly constant or stable, or whether they are instead likely to vary in an unstable manner (Weiner et al. 1971). Controllability refers to whether or not the individual is able to control the causes of the failure, with internal causes such as mood or fatigue being less controllable than internal causes such as the amount of effort expended, for example (Rosenbaum 1972).

Recent work on attributions suggests a focus on failure ascriptions, how the core causal characteristics of the failure are identified (Homsma et al. 2007) based on the two dimensions of locus of causality (internal vs. external) and stability (stable vs. unstable). The locus of causality is one of the most frequently studied dimensions of attributions (Zacharakis et al. 1999), and it can be empirically difficult to distinguish between locus of causality and controllability, with internal causes being quite similar to internally controllable causes of failure (Dixon et al. 2001; Ingledew et al. 1996; McAuley et al. 1992; Weiner 1986). Interpretation and meaning concerning failure experiences often include dimensions of control for the causes and the extent of personal responsibility combined together (Homsma et al. 2007). For example, an entrepreneur may say he has failed because he did not devote enough time or effort to the venture (an internal and controllable cause) or alternatively may say he has failed because of a downturn in the economy (an external and uncontrollable cause). Therefore, we follow the work of Homsma et al. (2007) and their focus on two dimensions of failure ascriptions—locus of causality (which also infers controllability) and stability.

We should note that one of the challenges in attribution research is that these dimensions are conceptually distinct, but also highly interrelated. For example, internal ascriptions are typically thought to be unstable, meaning that the entrepreneur is more likely to have beliefs that they can change whatever they believe caused the failure if they also believe those causes were internal. Similarly, an entrepreneur who makes external ascriptions for their failure is more likely to also make stable ascriptions, suggesting that their view is that the failure was not their fault and that the conditions that caused the failure cannot be changed. This has important implications for lessons they perceive to have learned from the failure, or not, as we explain in detail below.

3 Hypotheses

3.1 Internal unstable ascriptions and perceived learning

Research evidence suggests that when errors are ascribed to internal and unstable causes, more functional behavior is likely to result (Abrahamson et al. 1978; Homsma et al. 2007; Weiner 1985). This is because such ascription implies that (1) the cause that led to the failure is not necessarily going to occur again because it is unstable and (2) the individual may still have the capability to achieve a desirable outcome through the use of different strategies, effort, or other factors within the individual’s control (Homsma et al. 2007). Individuals making such ascriptions can still expect positive results in achieving their goals and are more likely to feel personal control over such results (Homsma et al. 2007). They therefore are likely to take an active task-oriented approach to those goals (Dweck 1975), such as through acquiring more training to help them address deficiencies (Jenkins 2012) or expending more personal effort with their subsequent venture (e.g., Lant et al. 1992; Weiner 1983).

Internal unstable ascriptions such as entrepreneurs blaming failure on their lack of entrepreneurial skills or management know-how will spur questions such as “What could I have done better that I can change?” and encourage entrepreneurs to pursue “counterfactual thinking”—the tendency to imagine different outcomes in a given situation than what actually happened (Baron 2004). This important entrepreneurial capability (Baron 2004) is highly relevant because such counterfactual thinking can have profound effects on understanding cause-and-effect relationships, subsequent decision making, and task performance (Markman et al. 2002; Roese 1997). Counterfactual thinking can influence the extent to which individuals who fail bounce back by trying to imagine how things could have turned out better and how their learning may be enhanced in their current venture. This leads to more exploratory behavior and higher quality strategies for avoiding the mistakes in the future (Graham 1991; Homsma et al. 2007). Such counterfactual and productive thinking is more likely to occur when entrepreneurs attribute their failure to internal unstable causes, since this is when they are likely to believe that there are behaviors, strategies, or skills that can change their future performance so it is not a repeated failure, and they are also more likely to believe that they themselves can change those things to achieve better outcomes. In support of this, Yamakawa et al. (2013) found that internally attributed causes of failure (they did not measure stability) lead to higher subsequent venture growth, at least for the first few venture failure experiences. Accordingly,

Hypothesis 1

Internal unstable ascriptions for failure will be positively associated with the amount individuals perceive they have learned from the failure.

3.2 External stable ascriptions and perceived learning

In contrast, when errors are assigned to external stable causes, perceived learning is less likely to occur. Those who ascribe their failures to external forces are less likely to learn the valuable lessons available from the experience of failure, since they are likely to interpret such causes as outside of their personal control (Homsma et al. 2007). They may believe that they have failed due to factors such as environmental uncertainty, competition, changes in customer demographics and preferences, or simply, “bad luck.” Because these causes are outside of the person, entrepreneurs often feel there is little they can do to alter those causes. Ascribing failures to external stable causes will spur little motive to examine previous decisions, behaviors, and actions that contributed to the failure, so very little reflection or opportunity for learning (Jenkins 2012) or beliefs/perceptions that they have learned from the failure. This results in a state of “learned helplessness” (Abrahamson et al. 1978; Caron and McGrath 1999; Dweck 1975) or self-denial (Friedman 2004) where the entrepreneur may venture again, but will have little opportunity or motivation to learn from their previous failure. Entrepreneurs who ascribe failures to external causes are less likely to revise their mental models or approach to entrepreneuring because they believe something outside of their own behaviors or strategies caused the failure (Jenkins 2012), and therefore, they have no need to change any of their behaviors. In addition, any counterfactual thinking that occurs related to an external attribution is likely to be unhelpful, because such “what-ifs” are about factors other than the person’s own actions (Jenkins 2012).

Further, failure can be painful, and while external ascriptions can be made because the entrepreneur truly believes the failure was due to something outside of themselves (other people or environmental factors), they can also be made in order to protect oneself from the challenges to self-esteem of ascribing failures internally. Ucbasaran et al. (2011) argue that some entrepreneurs attribute their failure to external causes in order to maintain their self-esteem, and in doing so, they often do not learn from such failures. Taken together this evidence suggests the following:

Hypothesis 2

External stable ascriptions for failure will be negatively associated with the amount individuals perceive they have learned from the failure.

3.3 The moderating influence of time to restart

We suggest that time between a failure and when an entrepreneur starts another venture will moderate the impact of failure ascriptions on subsequent learning. Many scholars argue that entrepreneurs can only learn from a venture failure with the passing of time. Cope (2011), for example, argues that entrepreneurs have to distance themselves from a loss to be able to learn from it, and Shepherd and colleagues suggest that time to deal with the loss of a venture is important to one’s ability to recover and venture again following that loss, adding that some entrepreneurs may gradually distance themselves from their ventures through “anticipatory grief” processes prior to the actual failure. Longer time intervals may also be needed when the financial cost of a business failure is high (Shepherd et al. 2009).

Building on their arguments, however, we suggest a rather contrary argument proposing two major reasons why starting another venture sooner, rather than later, after failure may have beneficial implications for learning from failure. First, the length of time taken to recover from failure and to start up another business may simply represent the prevailing hardship of overcoming grief that interferes with learning from the failure (Shepherd 2003). The longer the time taken to start up another business, the greater the possibility of the entrepreneur being unable to recover from grief associated with the loss of the business (Shepherd 2003; Shepherd et al. 2009). However, Jenkins et al. (2014) found variability in grief experiences such that when entrepreneurs interpret a failure as involving loss of self-esteem (which occurs when they perceive the venture failure as a personal failure), they are more likely to experience grief from the failure experience, but that some entrepreneurs do not experience failure as a personal loss and therefore experience less (or no) grief from the venture failure. We suggest then that a shorter time period before starting another venture may allow individuals to learn more effectively and quickly from failures, providing a way for entrepreneurs to look forward to and take steps toward the future rather than focusing on the negative emotional response they may be feeling concerning the past failure (Cope 2011). Support for this also comes from Parker (2013), who found that the benefits of learning from one venture experience on subsequent venture performance are temporary and eventually die away, and that the longer the gap between one venture and the next, the more such effects have depreciated.

More specifically, we argue that time to restart will interact with failure ascriptions in impacting learning from failure. We suggest that the positive effects of internal unstable ascriptions on learning will be heightened by a shorter time to restart. If individuals that make internal unstable ascriptions for their failure take a long period of time to restart another venture, this may indicate that a high level of emotional pain is inhibiting entrepreneurs from recovering from the grief produced by the prior failure because they are caught up in blaming themselves for the failure and experience a loss of self-esteem and sense of personal failure due to this self-blame (Jenkins 2012; Jenkins et al. 2014). These strong negative emotions could prevent them from closely examining the failure in a timely manner, and therefore erode learning opportunities from the failure. Perceived learning may be more poignant and specific when sought sooner rather than later after a failure. Therefore, while the combination of strong internal unstable ascriptions for failure and an extended time between failure and re-emergence may erode learning from failure (Shepherd 2003), the combination of strong internal unstable causal ascriptions and a shorter time to start another venture should result in greater learning from the previous failure.

A second reason we suggest there may be beneficial effects of entrepreneurs starting a new venture sooner after a failure is simply that too much waiting time leads the knowledge and skills garnered from the prior failure to be perceived as obsolete. Industry-specific experience involves interactions with buyers, suppliers, distributors, and other stakeholders, which allows accumulation of knowledge about opportunities and threats unique to each industry (Kor et al. 2007). The knowledge and skills that may have been useful in the past can easily become obsolete as the industry evolves, contacts move-on, and technologies change (Song et al. 2008). The longer one waits the less applicable are the industry-specific prior skills and knowledge gained through the failure. In the high-velocity environments in which many entrepreneurs operate, the rigid commitment to insights from previous industry experience may be counterproductive particularly where timely adaptations to changes in demand, competition, and technology are essential for success (Chandler and Hanks 1994). Kawakami (2007) also refers to this waiting time as the “aging effect” and the “depreciation effect” of learning. The longer they wait, the more entrepreneurs may begin to feel that the lessons from failure are no longer applicable to their next venture. Simply put, time may diminish the development of the sense of learning from the failure.

This may be particularly relevant for entrepreneurs who ascribe their failure to external stable causes, since such causes are likely to be embedded in the industry environment of the firm, rather than within the individual entrepreneur. External stable attributions help an individual cope with failure and maintain their confidence (Luthans and Youssef 2004; Weiner 1985), making them more capable of venturing again quickly (Jenkins 2012). When entrepreneurs quickly restart another venture, they can capitalize on their knowledge of the industry and its potential pitfalls in their new firm. Entrepreneurs therefore may believe that they have learned more from a failure when they have ascribed the causes for it to external stable causes and they quickly restart another venture. Accordingly,

Hypothesis 3

Time to re-emerge from a failure moderates the relationship between internal unstable ascriptions for failure and perceptions of learning from the failure. Specifically, the faster individuals start another venture after a failure, the stronger the relationship between internal unstable ascriptions for failure and perceptions of learning from the failure.

Hypothesis 4

Time to re-emerge from a failure moderates the relationship between external stable ascriptions for failure and perceptions of learning from the failure. Specifically, the faster individuals start another venture after a failure, the more the negative relationship between external stable ascriptions for failure and perceptions of learning from the failure will be mitigated (less negative).

3.4 The moderating influence of domain abandonment

Another aspect of learning from failure has to do with whether the failed entrepreneur starts a subsequent venture in the same industry domain as their failed venture, or whether instead they abandon that domain and start a new venture in a new domain (Kawakami 2007). While Yamakawa et al. (2013) refers to domain abandonment as a potential outcome of external attribution of failure, we explore the role it plays in the failure recovery process such as perceived learning from the failure. We suggest that the positive impact of internal unstable failure ascriptions on perceived learning will be further strengthened when entrepreneurs start their subsequent venture in the same domain, and the negative impact of external stable failure ascriptions on perceived learning will be mitigated (somewhat less negative) if entrepreneurs start their subsequent venture in the same domain.

Domain abandonment basically means that many of the specific lessons from entrepreneurial failure may no longer be applicable due to the shifting of the domain. On the one hand, internal and unstable causes, by definition, are internal to one’s self and changeable by one’s self, and are therefore under more control of the entrepreneur (Homsma et al. 2007). If entrepreneurs remain in the same domain when they start another venture instead of completely abandoning the domain, they have greater opportunities to try different strategies or behaviors to do better in their subsequent endeavors, thus leading to greater chances of perceived learning. “Most learning is local or situated in that it is related to a specific technological, sectoral, social, and market position” (Sardana and Scott-Kemmis 2010: 443), which suggests that remaining in the specific domain will likely enhance the potential for learning.

On the other hand, when entrepreneurs attribute their failures to external stable causes they are likely to interpret these factors as beyond their control (Homsma et al. 2007) in the industry or product market they were operating in. While they may have an opportunity to try to address those industry conditions perceived to be constantly there (stable) if they remain in the same domain, they lose even the opportunity to apply the lessons learned if they abandon their previous domain. Unfortunately, some individuals who experience performance downturns due to external causes may pursue a strategy of shrinking or consolidating existing domains (Ford 1985), or starting a subsequent venture in an entirely different industry domain. Such domain abandonment for entrepreneurs means that many of the specific lessons from the failure, such as better understanding of the industry conditions one ascribed the failure to (the external stable causes), may no longer be applicable due to moving to a new industry domain, which is likely to further decrease the amount an individual perceives to have learned from the entrepreneurial failure experience. Frankish et al. (2013: 81) note that “learning is strongest when situations are repeated” among other conditions,Footnote 2 and repeated situations are quite rare in entrepreneurship since conditions change so rapidly, particularly in new venture start-ups. Entrepreneurs who abandon their venture domain after failure are less likely to learn from the experience because such domain abandonment adds to the newness of the context of the new venture start-up, making learning less likely to occur. Accordingly,

Hypothesis 5

Domain abandonment after a failure moderates the relationship between internal unstable ascriptions for failure and perceptions of learning from the failure. Specifically, the positive relationship between internal unstable ascriptions for failure and perceived learning will be strengthened (more positive) when individuals remain in the domain of their failed venture with their subsequent venture.

Hypothesis 6

Domain abandonment after a failure moderates the relationship between external stable ascriptions for failure and perceptions of learning from the failure. Specifically, the negative relationship between external stable ascriptions for failure and perceived learning will be strengthened (more negative) when individuals abandon the domain of their failed venture with their subsequent venture.

Our conceptual model is summarized in Fig. 1.

4 Data and methods

4.1 Entrepreneurship in Japan

Depending on the “entrepreneur-friendliness” of the institutional environment, it can be challenging for individuals to start up a venture, or to have a second chance to start another business upon failure (Simmons et al. 2014). For example, countries vary in the entrepreneur-friendliness of bankruptcy laws that impact entrepreneurship development around the world (Lee et al. 2011; Peng et al. 2010). Cultural values and norms, for example, “tall poppy syndrome” (i.e., knocking high achievers) or societal “intolerance of failure” (i.e., significantly negative public reaction to failure), discourage individuals from starting up a venture, let alone coming back from a failure (Efrat 2006).

In Japan, where failure is intolerable and stigmatized, society rarely allows individuals to accept failure or bounce back from the perceived shame of failure (Economist 2008) and sometimes entrepreneurs even commit suicide after failure (Time 1999). This extremely negative societal perception of failure has led to Japan experiencing a stifling of entrepreneurial activities and slowdown in innovative activities, and recent years have been called the “Lost Decade” (the 1990s) of Japan’s economy (Establishment and Enterprise Census 2006; Harada 2005).

Despite such low tolerance for failure, greater risk, and a hostile environment to entrepreneurship, serial entrepreneurship does happen in Japan. Half of the failed entrepreneurs desire to come back, and 9.6 % of them actually start another business within 2 years (Kawakami 2007). The opportunities to recover and re-emerge exist even in this harsh climate for entrepreneurial failure. If individuals in Japan were to understand that not only surviving a failure is possible, but also learning from failure through applying lessons to a new and successful venture is possible, perhaps the extreme social stigma associated with failure would be less daunting to nascent or would-be entrepreneurs. Therefore, we believe that within this hostile climate in Japan, using a sample of Japanese entrepreneurs with failure experience is quite appropriate for understanding the critical implications of failure for learning, specifically in terms of entrepreneurs believing that they can apply the lessons learned from failure in subsequent entrepreneurial endeavors.

4.2 Data source

Since 1969Footnote 3, the National Life Finance Corporation (NLFC: Kokumin-seikatsu-kinyuu-kouko) has established itself as a major institution that conducts research on new ventures in Japan. In 1991, and thereafter, NLFC has conducted a large-scale survey of new ventures every summer and has published the aggregated result annually by the name of “White Paper on Business Start-ups (Shinki-kaigyo-hakusho).” A number of studies have capitalized on the advantages associated with using the data (e.g., Harada 2003; Masuda 2006), including data bridging various industries, detailed information on entrepreneurs’ background (e.g., age, gender, education, previous business experiences), and financial data of new ventures (e.g., amount of initial capital, sources of funding, expected sales revenue before start-up, actual sales revenue at present).

In August 2001, NLFC carried out an additional study—a follow-up survey in the hopes of capturing data on entrepreneurs’ failure experience. Approximately 5,000 surveys were mailed out, and only those entrepreneurs with failure experience were asked to complete and return the surveys. From this mailing, 236 surveys were returned. Statistically speaking, as a benchmark, new venture studies on surveys conducted by NLFC (e.g., Higuchi et al. 2007; Suzuki 2012) report that only a little more than 10 % of respondents have prior founding/managing experience. Whether or not these serial/portfolio entrepreneurs had experienced failure in their prior ventures is not certain. Thus, even if we were to assume that 10 % of the 5,000 survey recipients had failure experience, this would correspond to a response rate of 47.2 % (236/500) as the most conservative estimate for this study, since many of the 5,000 survey recipients (90 % or more) are unlikely to have had a failure experience and therefore disqualified themselves from completing/returning the surveys.

The current dataset is based on the aggregated result of this “Survey of Entrepreneurs Starting their Businesses for the 2nd-time” (Nidomeno-kaigyou-ni-kansuru-anketo). By definition, only entrepreneurs who have started a second business (or more) after failing in their first attempt are included in this sample. Therefore, the survey data are ideal to address our research questions. Data on entrepreneurial failure at the individual level are not easy to obtain, and studies have reported interesting findings from the data (e.g., Kawakami 2007; Yamakawa et al. 2013).

4.3 Measures

4.3.1 Perceived learning from failure

Our dependent variable is based on respondents’ answers regarding their experience of entrepreneurial failure and to what extent the respondents indicate they are making use of their previous failure experience in their current venture.Footnote 4 Answer choices range from I am “not particularly making use of previous failure experience in my current venture (learning: low)” to “very sure of making use of previous failure experience in my current venture (learning: high)” plotted on a five-point scale. This measure is consistent with that used by Homsma et al. (2009) who assessed learning using questions such as “did the error lead to new insights and/or ideas within the organization?” This is also consistent with the majority of research on entrepreneurial learning, which relies upon self-reported learning data (De Clercq and Sapienza 2005; Sardana and Scott-Kemmis 2010). We discuss potential limitations and advantages of using a self-reported measure of perceived learning from failure below.

4.3.2 Ascriptions for failure

Respondents were asked to identify up to three explicit causes for their venture failure, as well as to indicate which one was the primary reason. Prior research indicates that explicit causes do not lead to equivalent assessments of causal-attribution dimensions (Van Dyck et al. 2005). While Yamakawa et al. (2013) created “internal attribution of blame,” a percentage variable from the three causes of failure identified (e.g., how many of the three are attributed internally), we instead categorized these explicit causes into ascriptions that were “internal/external” and “stable/unstable” as was done in Homsma et al. (2009). Each cause was separately coded into four failure ascription categories of internal/unstable, external/unstable, internal/stable, and external/stable.Footnote 5 In this way, each respondent has up to three “counts” distributed across the categories. For example, one respondent may have “1” for internal/unstable and “2” for external/stable. We separately analyzed these causes based on just the single primary cause of failure listed by respondents (reported in Table 1) and based on (up to) three causes of failure listed by respondents (reported in Table 2). Since the results of our analyses were qualitatively similar to both sets of responses included, and given that individuals see different aspects of failure (Shaver 1985) and that failure is often attributed to multiple factors instead of just one, we chose to report analyses using all three causes. While we theoretically focused on two potential ascription categories, internal unstable and external stable because those categories are found to have the most and least likelihood of learning (Jenkins 2012), we conduct our analyses using all four categories in order to be thorough.

4.3.3 Time to restart

This variable is based on the length of time (in months) from when respondents experienced failure in their previous business until they founded their current venture.Footnote 6 Yamakawa et al. (2013) label this as “time to reentry” and use it as a control variable in their models. Since in our hypothesis we are interested in how quickly an entrepreneur re-emerges from a failure and starts a new venture after failure, we created a new variable (and named it “time to restart” to differentiate it) by dividing 1 by the length of time so that a higher score indicates a shorter time to restart, and a lower score indicates a longer time before the entrepreneurs started their next venture. Our sample shows that respondents took 14 months on average to restart another business (ranging from less than a month to nearly 30 years).

4.3.4 Domain abandonment

To measure domain abandonment, we created a binary variable from respondents’ answers concerning the industry in which they started their subsequent venture. This variable equals 1 if respondents changed their industry between their failed venture and their new venture (domain abandonment), and 0 otherwise (Kawakami 2007; Yamakawa et al. 2013).

4.3.5 Control variables

We control for five sets of factors that might influence perceived learning. First, we created dummy variables to control for industry effects (Chrisman et al. 1999; Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1990) that have implications for overall infrastructure (e.g., resources) to start and restart a business upon failure. Our data represented respondents from nine major industries: manufacturing, wholesale, retail, restaurant, construction, transportation, consumer service, governmental service, real estate, and others. Second, we coded conditions under which entrepreneurs exited their previously failed businesses as dummy variables—voluntary liquidation or bankruptcy filing—to control for the nature of the failure that may have an influence on learning and recovering from the failure (Lee et al. 2011). Third, we calculated venture size of the failed business by the number of employees to control for organizational characteristics, as well as current venture age in months to control for any time-effect on varying perception of learning (Barkham 1994; Song et al. 2008). Fourth, we coded individual characteristics of the entrepreneur (Barringer et al. 2005; Brush 1992; Fischer et al. 1993) including gender (1 = male), age at new start-up (in years), industry experience (in months) as a proxy for knowledge, skills, and capabilities (Minniti and Bygrave 2001), and the extent of failure (number of previous failures) (Politis and Gabrelsson 2009). We included the amount of start-up financial capital (in thousand Yen) raised for their current venture (Forbes 2005; Tyebjee and Bruno 1984) to account for the variation in restart-up conditions, and whether they had financial debt from their previous failure (measured with a dummy variable of 1 if there was still debt remaining from the previous failure and 0 otherwise) since being able to learn and start a new venture can be a function of resource availability and constraints.Footnote 7

Finally, we created a binary variable based on respondents’ answers regarding the financial performance of the current venture to control for subsequent performance after failure (performance of the new firm following failure of a prior firm). This variable, profitability, equals 1 if the business is currently making profit, and 0 otherwise (still in the red). This was to control for the possibility that entrepreneurs’ responses concerning their prior failure experience might be influenced by the outcome of their subsequent actions (Martinko 1995). Essentially, individuals may indicate they learned more from their prior failure when they are successful in their next venture than when they are not, so we include this variable in an attempt to mitigate this influence on our dependent variable.

In order to maintain power considering our sample size, we carefully reviewed all control variables, tested them in groups (e.g., individual, firm, and industry levels), found that industry-level effects were only marginally significant, and therefore retained only individual- and firm-level control variables for further analyses.

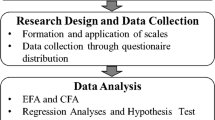

4.4 Analyses

In order to test our hypotheses, we utilize hierarchical regression models. By controlling for main effects, hierarchical regression models enable us to examine the added explanatory variance of each independent variable. Following the conventional approach, we test models in which we enter control variables, main variables, and then interaction terms. The technique of moderation is useful for testing two-way interactions among the variables of interest (Dess et al. 1997).

For robustness checks, we also utilized ordinal logistic regression analysis to test our hypotheses. While the psychological distance between the points of the scale developed to measure the amount of learning from failure seems equal, this is to address the case when it may be unequal. By accounting for a possibility of using a non-interval outcome variable, ordinal logistic regression produces a more appropriate estimate (Kleinbaum and Klein 2010). The results are qualitatively similar to our findings using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression, so we report the latter.

5 Results and findings

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics. Our sample of entrepreneurs includes a total of 220 venture founders who have experienced failure and started another firm. Approximately 86 % of them are male. Average age at start-up is 48, ranging from 24 to 75 years. Industry working experience prior to start-up is an average of 9 years, and ranging from 4 months to 35 years. Average size of the new venture is 7 employees, ranging from none (only self) to 113.

In order to capture any possible multicollinearity problems among our variables, we checked all variance-inflation factors (VIFs) and condition indexes. Individual VIFs greater than 10 and an average greater than 6 are generally seen as indicative of severe multicollinearity (Kleinbaum et al. 1988). In our data, the maximum VIF was 1.45, and the mean VIF was 1.16. This suggests that multicollinearity is not a problem in our study.

Table 4 depicts the hierarchical regression model estimates of perceived learning from entrepreneurial failure. Model 1 is the base model containing only the control variables, models 2 and 3 include main effects, and models 4 through 6 include the interaction terms. The increasing explanatory power among the models is depicted in the R-squared changes. In terms of the control variables in our models, results did not indicate any difference in the ascription-learning relationships based on gender. We find, however (across all models), that age at start-up is negatively associated with perceived learning and that subsequent performance is positively associated with perceived learning. We expand on these findings in the discussion section below.

In Hypothesis 1, we examine the effect of internal unstable failure ascriptions on the amount of perceived learning from the failure. The results are positive and significant in the main-effect models (B = .509; p < .01 in model 2), and thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Hypothesis 2 examines the effect of external stable failure ascriptions on the amount of learning from the failure. The results are negative and significant in the main-effect models (B = −.383; p < .01 in model 2), supporting Hypothesis 2. While we did not hypothesize main effects for internal stable and external unstable ascriptions, we note that neither has a significant effect on learning in model 2, so they are dropped from subsequent analyses.

In Hypothesis 3, we explore the moderating influence of time to restart on the relationship between internal unstable failure ascriptions and learning from failure. The positive and significant interaction term in model 6 (B = .659; p < .01) indicates that Hypothesis 3 is supported. The non-significant result in model 5 shows that Hypothesis 4 (moderating influence of time to restart on the relationship between external stable failure ascriptions and learning from the failure) is not supported. We also tested for a curvilinear effect of time to restart on learning from failure, as a robustness check for our findings, but did not find significant results.

In Hypothesis 5, we explore the moderating influence of domain abandonment upon previous failure on the relationship between internal unstable causal ascriptions and learning from the failure. Results from model 4 show no support for Hypothesis 5. The negative and significant interaction term in model 6 (B = −.479; p < .01) provides support for Hypothesis 6, that there is a moderating influence of domain abandonment on the relationship between external stable failure ascriptions and learning from the failure.

Our findings suggest that internal unstable failure ascriptions are significantly and positively associated with the amount of learning, especially when entrepreneurs take a shorter time to start up another venture, while external stable failure ascriptions are significantly and negatively associated with the amount of learning, especially when entrepreneurs abandon their previous industry domain. Graphs of the significant moderating influences (Hypotheses 3 and 6) are presented in Fig. 2a, b, respectively.

6 Discussion

Failure is a necessary part of entrepreneurship since opportunity creation can occur through a process of trial and error, and failure of particular opportunities can be an essential part of the path toward career success (Singh et al. 2007). Several scholars have examined how entrepreneurs react to failure including their emotional responses which may involve significant levels of grief (e.g., Jenkins et al. 2014; Shepherd 2003), and others examine the coping processes entrepreneurs go through to deal with their failures and learn from them (e.g., Cope 2011; Singh et al. 2007). For the majority of these studies, however, the entrepreneurs studied had not yet started a new venture, so the extent to which the failure experience led to perceptions of learning things that could be applied to a new venture was not examined.

We add to prior work on entrepreneurial failure and learning by examining entrepreneurs who have taken the opportunity to venture again after a failure in order to try to apply the lessons they think they have learned. We specifically focus on the two types of entrepreneurs who are most likely to reenter self-employment after experiencing a firm failure (Jenkins 2012): (1) those who have reflected on their role in contributing to the failure and are thus likely to change how they act in their new ventures (those with internal unstable ascriptions for their prior failure) and (2) those who focus on the role of external conditions in their failure and are thus less likely to change how they act (those with external stable ascriptions for their prior failure). Jenkins (2012) suggests that the first group is most likely to learn from their failure and the second group is least likely to learn from their prior failure. Our results are consistent with those of Jenkins in this regard; however, we add to these findings by also finding evidence that time to restart the subsequent venture and domain abandonment moderates these relationships. Our results suggest that internal unstable ascriptions for failure lead to much greater perceived learning and that the combination of internal unstable ascriptions and shorter time to restart further enhances that learning. In contrast, external stable ascriptions alone and combined with domain abandonment decreases perceived learning. There are a number of contributions from our study.

6.1 Contributions

First, by drawing on insights from the cognitive literature on attributions and ascriptions we are able to better understand the mechanism underlying the link between prior failure and subsequent perceptions of learning. In response to a call for a more nuanced view of failure and its implications (Cope 2011; Ucbasaran et al. 2013), and in particular, the relationship between individual attributions for failure and recovery from failure (Cardon et al. 2011) we bring additional insights to the learning literature. As Baron (2004) and Shane et al. (2003) have emphasized, entrepreneurship arises most fundamentally from the actions of particular persons. Consequently, understanding why and how they learn and act as they do is critical to understanding the entrepreneurial process. In this study, we have partially filled in the gap of clarifying the mechanism of how entrepreneurs ascribe blame for their failures and perceive to have learned from their previous experience by finding evidence that causal ascriptions made on the part of individuals matter. This is consistent with prior work in psychology that has repeatedly demonstrated that assigned causes for errors can lead to considerable differences in behaviors (Weiner 1985).

Our study builds on the importance of learning by doing and learning based on performance triggers. We focused on entrepreneurial failure as an event (context) and examined how reflection on negative mistakes or crises, more specifically, causal ascription of failure, affect perception of learning from failure. We extend prior work showing that critical events within the entrepreneurial process stimulate learning to show that not only does deeper reflection create higher-level perceived learning from experiences (Cope 2003), but also the type of reflection in the form of causal ascriptions impact the extent of perceived learning from failure. Entrepreneurs are more likely to reflect on the mistakes to determine their causes, and to prevent its repetition (Marsick and Watkins 1990), and we add to this argument by showing that “how” they attribute the cause of failure can determine how much they perceived to have learned. By defining learning as an individual’s belief that they can apply the lessons learned to their next venture, we also add to our understanding of the complex relationship between reflection and action (Cope 2005). By examining how causal ascription (reflection) impacts individual’s ability to focus on the future (action) rather than the past, this in turn allows us to predict how they will use what they have learned from previous experiences.

It is important to note that we examine these relationships in a sample of entrepreneurs who have failed and chosen to venture again. While Cardon and McGrath (1999) provide an interesting exploration of attribution and recovery, their sample is of students rather than entrepreneurs and does not empirically examine the question of learning subsequent to entrepreneurial failure. Similarly, Cope (2011) has intriguing suggestions about failure and recovery, but had only one entrepreneur in his sample who had recovered enough from failure to go on to start another venture. The best opportunity for learning to occur from failure is when that learning can be applied to a new venture (Jenkins 2012; Shepherd 2003). By utilizing a sample of entrepreneurs who have experienced failure but recovered enough to start another venture, we were able to look at perceptions of learning as they are applied to the new venture rather than in the abstract, which as a field we previously had very little data on.

When it comes to ascriptions of the cause of failure, our results practically suggest that entrepreneurs should explore what went wrong when faced with failure, and even the potential for multiple causes of the failure. This is akin to Cope’s (2011) discussion of “learning about one’s venture and its demise,” which is important in order for an entrepreneur to also experience “learning about venture management,” which means taking the lessons from the failure experience and applying it to lessons at the firm-level going forward. In order for entrepreneurs to realize the potential functional outcomes from the negative experience of failure, they have to be willing to examine the failure and assess its causes. Functional behavior after error occurrence is optimized by analyzing that error, among other factors (Van Dyck et al. 2005).

While our results certainly suggest that internal ascriptions are beneficial so that entrepreneurs accept responsibility for the failure and can discover what lessons can be taken away, and unstable ascriptions are also beneficial so that entrepreneurs believe in the potential to change those causes and therefore succeed in future endeavors, we recognize that failure ascriptions cannot be forced or mandated in those directions. Entrepreneurs will ascribe the causes of their failure based on their own assessment of why their venture failed, as well as based on their emotional experiences surrounding that failure (e.g., Jenkins et al. 2014; Shepherd 2003). Perhaps training and guidance for entrepreneurs struggling to diagnose and focus on their failure would be helpful so that they can take a step back from the failure and learn how to engage in the dual processes of loss orientation and restoration orientation (Shepherd 2003), which can reduce emotional interference and enhance the ability of entrepreneurs to learn from failures. This suggestion recognizes that sense making for failure through causal ascriptions involves not only cognitions (analyzing why one might have failed), but also information both within and outside of the firm (what other firms failed and what the economic indicators look like), and emotions (if I blame the failure on external causes perhaps I will experience less grief). Such training could help entrepreneurs with the processes of ascription and interpretation to promote functional behaviors and greater coping following failure, as well.

For our second contribution, building on our attempt to unpack the mechanism of how learning from failure occurs, we find interesting boundary conditions that suggest the relationship between internal unstable ascriptions and perceived learning is further strengthened by the time entrepreneurs take to restart. In our data, the faster entrepreneurs started up another venture when they made internal unstable ascriptions, the greater the amount they believe they learned from the failure. This is interestingly in contrast to other literature that suggests that longer periods of time are typically needed for learning to occur so that an entrepreneur has a chance to recover from the grief associated with venture failure (Shepherd 2003, 2009). Cope (2011) suggests that entrepreneurs experience restoration (Shepherd 2009) from a failure through both distraction from the failure experience and looking forward and taking positive new steps not only to avoid the loss or grief feelings but also instead to help end those feelings by replacing them with positive emotional experiences. Cope discusses a three-step process of restoration including: (1) an initial break where entrepreneurs separates themselves from the failure in order to heal; (2) critical reflection to make sense of the failure; and (3) reflective action where entrepreneurs try to move on from the failure and pursue new opportunities. We add to Cope’s qualitative case study findings with our quantitative results suggesting that critical reflection through ascribing causes for failure combined with quick reflective action to venture again helps increase the potential for learning to occur following the initial failure. In particular, we suggest that faster restart makes the lessons fresh and more easily transferrable to the current industry circumstances, and reduces the potential problems associated with the “aging effect” of learning (Kawakami 2007). We see great potential for future research to more carefully look at the time it takes for each of these three steps in the restoration process.

Our results also show that the negative effect of external stable failure ascriptions on perceived learning is contingent upon whether entrepreneurs abandon their previous domains upon starting another business. We find that when entrepreneurs abandon their previous domain upon restart, their external stable ascription is significantly and even more negatively associated with the amount of learning from the failure. Essentially, when entrepreneurs blame conditions outside of their control for the failure, and subsequently abandon the industry or domain that the venture operated in, the chances that they are able to take lessons away from the failure experience to apply to a new venture in a new domain are much lower. Such a giving-up approach has been called “learned helplessness” (Brockner et al. 1983; Wortman and Brehm 1975), where individuals stop trying to achieve something they want (e.g., success in the prior domain) because they believe it is outside of their control and ability to achieve it. While this relationship has previously been suggested in psychology (e.g., Dweck and Leggett 1988), it has not yet been well substantiated in the entrepreneurship literature. In addition, it is quite interesting to note that neither domain abandonment alone, nor domain abandonment and internal unstable ascription together had a significant relationship with learning, but instead the interaction of domain abandonment and ascribing failure to external stable causes was most problematic for perceived learning.

Interestingly, two of our hypotheses were not supported. First, the negative effect of external stable ascriptions on learning did not vary with time to restart another firm. When entrepreneurs ascribed their failure to something outside of their control (external) that they had no ability to change (stable), they felt there were fewer lessons they could take from that to apply to their new ventures, regardless of how quickly or slowly they started their next venture. Similarly, the positive effect of internal unstable ascriptions on perceived learning did not interact with domain abandonment. It seems that entrepreneurs who felt personally responsible for the failure were motivated to apply the lessons learned from that failure experience to their new venture and were more likely to perceive that they were able to do so, regardless of whether they remained in the same industry domain or tried a new one for their subsequent venture.

It is also noteworthy that two of our control variables were significant across all models. “Age at start-up” showed a significant and negative relationship with the mount of perceived learning from the failure, indicating that the older and more mature the entrepreneur, the less they perceive to have learned from their failures. Another variable, “profitability,” showed a significant and positive relationship with the amount of learning from failure, as expected. Our results echo Martinko (1995) that causal attributions can be influenced by the outcome of subsequent actions. In our sample, it seems clear that successful individuals attributed their successes to their learning from their prior failure, which enhanced their perception of the amount they learned from the failure, essentially saying “I am successful now, I must have learned much from my previous failure.” This suggests that further research that captures attributions and perceptions of learning at the time of failure, especially prior to the start of a new venture, may offer new and interesting insights that would tease apart one’s attribution for the failure, assessment of learning for the failure, and later venture performance. We note, however, that our results presented and discussed above are robust when this success element is controlled for, suggesting that in addition to the effect of subsequent success of their new venture, their causal ascriptions had the effects described here.

A third contribution of our work is that we empirically substantiate our arguments through a relatively large-scale survey-based database of Japanese venture-founders who have previous failure experiences—to the best of our knowledge, one of the very first such endeavors in the literature following Yamakawa et al. (2013). The nature of the survey used has allowed us to expand the global scope of research on failure and learning, given the paucity of entrepreneurship research in Japan (Bruton and Lau 2008; Eberhart et al. 2011). Our results also build on the work of Yamakawa et al. (2013) by (1) broadening the scope of attribution dimensions examined from just locus of causality to also incorporate locus of stability and (2) examining the influence of failure ascriptions on perceptions of learning, a more subjective and personal outcome, than on subsequent venture performance.

Our findings suggest that in Japan not only surviving a failure is possible, but also learning from that failure and applying those lessons to a new and successful venture can and does occur. Perhaps the extreme social stigma associated with failure in Japan would be less daunting to nascent or would-be entrepreneurs if they were aware of the findings of this study in this regard. Moreover, recent research suggests that the changing institutional climate for entrepreneurship in Japan, specifically the laws regarding bankruptcy, is changing the incidence of both entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial failure in Japan (Eberhart et al. 2011; Efrat 2006). The more knowledge we have of the relationships between failure, learning, and subsequent venture success, the better, not only for understanding entrepreneurship in Japan, but also for understanding entrepreneurship in other parts of the world where tolerance of failure is low.

6.2 Limitations and future research directions

As with all studies, several limitations exist. First, despite the diagramed arrows in Fig. 1, the directionality remains uncertain, because the cross-sectional design of our study prohibits causal inferences. Since learning from failure is an outcome of a process that occurs over time, we suggest that a longitudinal approach is needed in the future in order to provide a more nuanced view of the causal mechanisms for how the process of learning from failure unfolds.

Second, our sample includes only entrepreneurs who failed and started a subsequent venture, and whose businesses were surviving at the time of our study. While this was a deliberate study design choice given our definition of learning as the ability to apply lessons to a new venture, we note that we cannot speak to all learning that might occur from failure, or generalize to “all” entrepreneurs who failed and decided not to venture again. An ideal sample for such a study would capture data from all new ventures in a population and follow them as they experience success and failure, and then subsequent restarts that occur that are then in turn successful or not. That said, our study is one of very few that does examine actual reentry into entrepreneurship after failure instead of intentions to start again (Yamakawa et al. 2013), or claims of learning without any application of those lessons (Jenkins 2012), which is a clear contribution over existing work.

Third, we acknowledge the possible constraints of our measurement. In particular, we relied on self-reported data, which may pose such potential problems as common method bias and recall-bias by respondents. Our measure was also captured at one point in time. A longitudinal view would allow us to examine the possible shift in one’s causal ascriptions of failure over time. For example, exploring the optimal balance between internal and external as well as unstable and stable attributions seems to promise interesting findings (Harvey et al. 2006). To mitigate these concerns and in order to assure stronger face validity to ascertain that our measures assessed the intended constructs under study, we carefully aligned the definitions, hypothesis-development arguments, and measurement. We also tested internal consistency by comparing results of random sample groups to confirm reliability.

Relatedly, we were unable to assess the “actual” cause of failure—the challenge being that every description or explanation for a failure is a perception or attribution that individuals make, and the “truth” is often only in the eyes of the perceiver (Weick 1995). Relying on entrepreneurs’ perception of causes of failure has been identified as a potential cause for bias in entrepreneurial failure research (Sarasvathy and Menon 2003; Shepherd and Wiklund 2006). However, when the research question itself is focused on the entrepreneur’s perception and interpretation of failure, this is not a cause of bias (Zacharakis et al. 1999; Jenkins 2012). In our study, we were not measuring or attempting to measure actual learning or actual causes of failure, but instead the entrepreneur’s own perceptions concerning the causes of their failure and perceptions of how much they did or did not learn from the failure that was applicable to their subsequent ventures. While it would be fascinating to study the relationship between attributions and actual causes (if such a thing were knowable) in their impact on outcomes such as learning, this was not the intent of the current study. We also note that our measure of perceived learning was based on a single item, which is a limitation of this study.

Finally, although the institution-specific environment was strongly intentional to take into account a variation in the nuance of failure for individuals in a single country, the empirical results derived from a sample of Japanese venture-founders may raise the concern that our findings are country specific. In this context, greater external attribution may be due to the importance of “face saving” or “life saving” considering the prevalence of suicide following failure in Japan (Time 1999). It is possible that in other countries, different cultural norms and inner mechanisms exist that affect the prospects of attribution and learning from failure in different ways (Ucbasaran et al. 2013). There also may be concerns with social desirability bias in respondents’ stated causes for failure, given this conservative context (Simmons et al. 2014). That said, Henrich et al. (2010a, b) have posited that Western societies are among the least representative populations concerning fundamental aspects of psychology, motivation, and behaviors, suggesting that the Japanese context of our study is perhaps more generalizable than others, perhaps even more so than the Western context. In addition, we note that our theorizing builds on prior work concerning entrepreneurial failure and learning completed in multiple countries, including Sweden (Jenkins 2012; Politis and Gabrelsson 2009), Finland (Huovinen and Tihula 2008), Uganda (Sserwanga and Rooks 2014), and the twenty-three countries in the GEM dataset (Simmons et al. 2014). Notwithstanding these limitations, we hope that future research builds on our study and expands our collective knowledge in this domain.

7 Conclusion

Given the pervasiveness of failures, and the importance of understanding how individuals discover/re-discover, create/recreate, and exploit/re-exploit opportunities and with what consequences (Shane and Venkataraman 2000), it is imperative that our attention be devoted to this important, relevant, and challenging research agenda on learning from failure (Ucbasaran et al. 2013). We have added to this effort by drawing from the literature on attribution and ascription to help understand learning after failure for those who choose to venture again in Japan. Our results suggest that, in particular, internal unstable failure ascriptions appear to enhance learning, especially when shorter time is taken to restart, while failure ascriptions to external stable sources alone and especially when combined with abandoning the domain of the failed venture appear to deteriorate such learning. We encourage additional research in this area.

Notes

The majority of work on entrepreneurial learning has relied on self-reported data (De Clercq and Sapienza 2005), which some scholars suggest does not reflect “real” learning (Frankish et al. 2013). We take a broad view of entrepreneurial learning as a process through which entrepreneurs experience, reflect, think, and act (Bailey 1986).

We note, however, that Parker (2013) found no evidence of performance differences in serial entrepreneurship for those who start ventures in the same industry versus a different industry.

Data for this secondary analysis were provided by the Social Science Japan Data Archive, Information Center for Social Science Research on Japan, Institute of Social Science, The University of Tokyo.

Respondents were also asked the ways in which the learning from failure was applicable to their subsequent ventures. Out of all respondents, 35 % of them referred to customer development (and marketing related) issues, 32 % of them raised product/service development issues, 26 % of them mentioned issues related to cost reduction, and 24 % of them referred to financing issues (among other factors).

For example, internal unstable causes of failure include lack of entrepreneurial skills, lack of managerial know-how, and lack of financial planning. External stable causes of failure include competition and environmental uncertainty.

We also used another variable “time to ‘decide’ to start up another business” which represents the length of time (in months) from when respondents exited their previous businesses until they “decided” to found their current business—to capture recovery in a more emotional sense. Results are qualitatively similar.

We also tested our model with the actual monetary value of debt, and results are qualitatively similar to our main findings, due to missing variables; however, the sample size was reduced from N = 220 to N = 99 when the actual monetary value of debt was used.

References

Abrahamson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., & Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in human: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49–74.

Aldrich, H. E. (1999). Organizations evolving. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Bailey, J. (1986). Learning styles of success entrepreneurs. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 6, 199–210. Babson College, Wellesley, MA.

Barkham, R. J. (1994). Entrepreneurial characteristics and the size of the new firm: A model and an econometric test. Small Business Economics, 6, 117–125.

Baron, R. A. (2004). The cognitive perspective: A valuable tool for answering entrepreneurship’s basic “why” questions. Journal of Business Venturing, 19, 221–239.

Barringer, B. R., Jones, F. F., & Neubaum, D. O. (2005). A quantitative content analysis of the characteristics of rapid-growth firms and their founders. Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 663–687.

Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 893–921.

Bettman, J., & Weitz, B. (1983). Attributions in the board room: Causal reasoning in corporate annual reports. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28, 165–183.

Boud, D., & Walker, D. (1990). Making the most of experience. Studies in Continuing Education, 12(2), 61–80.

Brockner, J. (2002). Making sense of procedural fairness: How high procedural fairness can reduce or highten the influence of outcome favorability. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 58–76.

Brockner, J., Gardner, M., Bierman, J., Mahan, T., Thomas, B., Weiss, W., et al. (1983). The roles of self-esteem and self-consciousness in the Wortman-Brehm model of reactance and learned helplessness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(1), 199–209.

Bruce, T. J., Tannenbaum, S. I., & Kavanagh, M. J. (1995). Applying trained skills on the job: The importance of work environment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(2), 239–252.

Brush, C. G. (1992). Research on women business owners: Past trends, a new perspective and future directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 2(1), 1–24.

Bruton, G. D., & Lau, C.-M. (2008). Asian management research: Status today and future outlook. Journal of Management Studies, 45(3), 636–659.

Burgoyne, J. G., & Hodgson, V. E. (1983). Natural learning and managerial action: A phenomenological study in the field setting. Journal of Management Studies, 20(3), 387–399.

Burke, L. A., & Hutchins, H. M. (2007). Training transfer: An integrative review. Human Resource Development Review, 6(3), 263–296.

Cannon, M. D., & Edmonson, A. C. (2001). Confronting failure: Antecedents and consequences of shared beliefs about failure in organizational work groups. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 161–177.

Cardon, M. S., & McGrath, R. G. (1999). When the going gets tough… Toward a psychology of entrepreneurial failure and re-motivation. In P. D. Reynolds, W. D. Bygrave, S. Manigart, C. M. Mason, G. D. Meyer, H. J. Sapienza, & K. G. Shaver (Eds.), Frontiers of entrepreneurship research. Wellesley, MA: Babson College.

Cardon, M. S., Stevens, C. E., & Potter, D. R. (2011). Misfortunes or mistakes? Cultural sensemaking of entrepreneurial failure. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(1), 79–92.

Cardon, M. S., Zietsma, C., Saparito, P., Matherne, B. P., & Davis, C. (2005). A tale of passion: New insights into entrepreneurship from a parenthood metaphor. Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 23–45.