Abstract

Implementing sustainable sourcing practices (SSP) relies strongly on organizational decisions and the motives behind these decisions. However, little is known about how SSP are influenced by organizational motives (OM). To address this gap, we developed a multifaceted framework based on stakeholder theory (ST) that enables enhanced knowledge of OM, such as instrumental motives (IM), relational motives (RM), moral motives (MM), and their influence on SSP by incorporating the moderating role of stakeholder pressure (STP). Data were compiled from 308 Pakistani manufacturing organizational respondents and assayed by partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The deliverables of SEM validated that all OM directly impact SSP. Further, STP expressively moderated the targeted relations in confounding ways and organizational size moderately distinguished small and larger organizations. Importance-performance map analysis also revealed that RM have a greater importance value (0.201) and MM have a greater performance value (71.833) than all exogenous variables. This research offers several key contributions. First, all three OM (IM, RM, and MM) significantly improve SSP directly, and with the moderation of STP and organizational size, which signifies the salience of ST and provide diverse conclusions. Second, OM operationalize SSP and suggest ways to execute them to meet the organizational environmental goals. Third, this study examines how SSP implementation requires the source function to reconsider its key motives for sustainability endeavors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Globalization of supply chains and the relentless pursuit of manufacturing cost reduction have had detrimental effects on the environment worldwide, particularly in developing countries where high-demand commodities are increasingly being produced (Qin et al. 2021; Rahman et al. 2023). Recently the matter has gained prominence. Awareness of these adverse consequences has risen, prompting stakeholders to drive organizations towards accepting responsibility and adopting a “Go-green” approach to overcome these ecological sustainability issues (Del Giudice et al. 2020; Yousaf 2021). The understanding is that manufacturing organizations that turn raw materials into finished items can begin their journey towards sustainability from the start of their supply chain operations, i.e., sustainable sourcing practices (SSP). SSP are the amalgamation of several activities that transform raw materials to finish products (Bui et al. 2021; Schulze et al. 2022).

The accelerated industrialization and outsourcing of low-end manufacturing and fabrication in emerging economies have generated apprehensions regarding the insufficient emphasis and oversight of ecological sustainability (Foo et al. 2018; Shahzad et al. 2020a). This trend has led to the propagation of unethical, dishonest, and irresponsible activities in sourcing, posing significant threats to ecological sustainability (Del Giudice et al. 2020; Qin et al. 2021). As businesses expand their operations globally, there is a growing need to address these challenges and promote more responsible and sustainable practices in sourcing raw materials to certify a sustainable future (Rehman et al. 2023). The prioritization of financial gains over environmental concerns, driven by organizational motives (OM) (Paulraj et al. 2017), coupled with the growing influence of shareholders in strategical decision making (Mirzaei et al. 2021), has resulted in a lack of foresight and economic pressure that has silenced the voices of numerous stakeholders (Rahman et al. 2023). Major customers of finished goods from emerging economies, such as the European Union (EU), are setting out a strategic plan for achieving sustainable development (SD) (Haque and Ntim 2022). The agenda of UN 2030 for sustainable development goals (SDGs) has pushed the international trade regulation regimes to take radical measures to support downstream and upstream supply chains (Awan et al. 2017). The resulting scrutiny and strict procedures have encouraged many international businesses to follow sustainable practices throughout their supply chains. With the addition of ecological, social, and economic criteria in the sourcing process, many organizations try to abide by SSP to minimize adverse social, environmental, and economic impacts (Pinto 2020; Chatterjee and Chaudhuri 2021). Stakeholder pressure (STP) and public pressure arising from noncompliance with sustainable procurement could harm businesses operating in developing countries.

Adopting eco-conscious sourcing practices, such as prioritizing renewable energy, enhancing product development, and effectively managing supplier relationships, fosters ecological sustainability by encouraging practices like recycling and reclamation. Moreover, these practices also lead to socio-economic benefits (Li et al. 2020; Shahzad et al. 2020b). Reducing waste costs and increasing competitive advantage are just two of the many benefits that SSP can provide (Ding et al. 2019; Del Giudice et al. 2020). Other advantages include lowering the risk of health and ecological liabilities and avoiding fines for environmental infractions (Jaafar et al. 2018; Mirzaei et al. 2021). Furthermore, with increased consumer environmental awareness, green products comprised of materials supplied by green suppliers can be unique selling features, improving sustainable organizational competitiveness.

While the advantages of adopting the SSP are evident, significant challenges are also to overcome. One such challenge is that the emphasis on green sourcing may decrease the pool of qualified vendors owing to the stringent ecological quality standards required (Bueno-Garcia et al. 2021). Implementing prerequisites, like supplier pre-qualification based on the requirement of certifications, will further raise the bar for the suppliers (Yousaf 2021). An additional challenge arises from internal employees who may oppose newly adopted sourcing practices, as these changes disrupt their established sourcing habits and conventional business processes (Del Giudice et al. 2020; Abdul et al. 2022; Schulze et al. 2022). A further challenge, perhaps the biggest, will be to get shareholders on board with the decision to sacrifice some part of the existing capital in return for future benefits (Rehman et al. 2023). Though Shahzad et al. (2020b) highlighted that STP (involving primary and secondary stakeholders) substantially drives CSR and green innovation. This positive impact is facilitated by the knowledge management process, enabling organizations to embrace sustainable and socially responsible practices. Earlier research has also emphasized the substantial impact of STP on green management practices directly and indirectly through OM (Shahzad et al. 2022a). Extant literature signifies that green management, green innovation, and sustainable practices aren’t only distinctive concepts but rather contain different implications. These studies also offer a limited perspective since they haven’t considered STP as a boundary factor since the pressure might differ among various organizations in this context. Thus, we have particularly focused on SSP with the integration of STP. Another study by Rehman et al. (2023) revealed that corporate motivation considerably impacts the adoption of SSP, though regulatory measures moderate the influence on these relationships. Nevertheless, this relatable study doesn’t explore the role of organization size as well as it only considers the role of regulatory pressure, providing limited information. Contrary, the current study incorporates the significance of diversified stakeholders in influencing SSP adoption, supported by top leadership motives. Furthermore, larger organizations possess more resources and can implement green and sustainable sourcing more efficiently than smaller ones (Shahzad et al. 2022b). Therefore, it was necessary to study in detail to gain more specific insights into how various STP and organizational sizes may drive the adoption of SSP. These realities have catalyzed the formulation of the framework upon which the present research stands. Thus, the primary aim of this work is to empirically discover the effect of various OM on the SSP under the pressure of diverse stakeholders and organizational size. Hence, the problem stated above and the vacuum in the extant literature drove this examination, following which the study topics are listed below, which aim to minimize the uncertainty around these interactions.

-

What is the influence of the several OM on SSP?

-

Do STP and organizational size moderate the association between each of the OM and SSP?

The current research serves the extant literature in a variety of ways. This research study fills the gap by examining the role of OM in adopting SSP under the moderation of STP and organizational size by employing structural equation modeling (SEM) in a novel way. Empirically, this study explores and validates the role of different OM on SSP following stakeholder theory. The significance of these motives may vary for different types of organizations distinguished based on industry, size, and scope of operations while adopting SSP. These least explored connections between study variables may have significant consequences for sourcing policies, as policies are likely to be more effective if they are tailored to the considerable motivations of specific target groups. The findings will enrich the empirical research on adopting SSP in the manufacturing industry and will be a chance to examine the role of stakeholders like regulators and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Besides, large and more resourceful organizations can implement green and sustainable sourcing quicker than others, which can be a differentiating element from small and less resourceful organizations while executing SSP. This research explores an unexplored area by examining the impact of OM, STP, and organizational size on adopting SSP. The study aims to reveal the driving forces behind adopting sustainable sourcing and how various motives, moderated by STP and organizational size, influence SSP, thus, providing significant insights to organizations, policymakers, and environmental agencies, enabling them to understand the factors influencing sustainable sourcing and make informed decisions to promote sustainability in business operations. The theoretical foundation and hypothesis are signified in the next section, succeeded by the research methodology, results, discussion, conclusion, and implications.

2 Literature review

2.1 Theoretical background

According to stakeholder theory (ST), the impact of numerous stakeholders inspires enterprises to implement certain environmental practices to boost SD (Shahzad et al. 2022a). Accordingly, Freeman (1984) well-defined stakeholders as “a group or an individual that can affect or is affected by the achievement of an organization’s purpose.“ There are primarily two types of stakeholders: primary and secondary. Primary stakeholders include customers, employees, shareholders, and regulatory/government bodies. Secondary stakeholders encompass the media and various NGOs (Helmig et al. 2016; Shahzad et al. 2020b). Recently, stakeholders’ perceptions of environmental concerns have markedly broadened. STP greatly influences organizational motives (OM) and decision making; in particular, when stakeholders can influence the endurance of the firm (Baah et al. 2021). Organizations face growing pressure from various stakeholders to formulate strategies, procedures, and policies that prioritize environmental concerns (Del Giudice et al. 2020; Rehman et al. 2023). This concept describes examples for instigating specific environmental policies (Sarkis et al. 2011). Previous investigation has conceded a substantial association between STP and ecological management practices pursuing ST (Shahzad et al. 2020b). Furthermore, organizations reveal that applying STP principles to address ecological concerns substantially impacts improving eco-friendly performance (Gu et al. 2014).

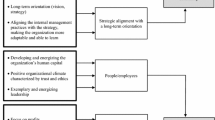

As stakeholders have become more aware and knowledgeable about green production practices, industries have been compelled to completely overhaul their entire life cycle, encompassing sourcing, production, and disposal processes (Jaafar et al. 2018). The strategic influences exerted by different stakeholders on organizations vary considerably, making it challenging to quantify their impact (Shahzad et al. 2022a). The extent of STP can be primarily determined by three key features: “power, legitimacy, and urgency”. “Power – the stakeholder’s power to influence the firm; Legitimacy – the stakeholder’s relationship with the firm; and Urgency – the stakeholder’s claim on the firm” (Yu and Choi 2016). Following the same ethos, Shahzad et al. (2022a) emphasized that STP directly influences green management practices by following ST. Importantly, sustainable sourcing throughout the supply chain helps organizations cut costs, boost efficiency, and boost financial performance in emerging nations (Bueno-Garcia et al. 2021; Qazi et al. 2022). Rahman et al. (2023) emphasized that four key sourcing practices: internal environmental management, suppliers and customers collaboration, green procurement, and environmental-friendly design significantly impact sustainable performance. Besides, Del Giudice et al. (2020) acknowledge three classes of circular economy practices, such as relationship, design, and HR, which are crucial in boosting firm performance from circular economy aspects. Further, Zhou et al. (2023) also highlighted that sustainable logistics management influences organizational circular economy practices and sustainable performance. Besides, Ambekar et al. (2019) identified numerous practices related to SSP through a comprehensive literature review. These sourcing practices include pressure from focal firms, supplier relationship management, monitoring, collaboration, certification, reducing supplier risk, multi-sourcing, lean supply, batch sizing, carbon tax, etc. (Abdul et al. 2022). The practices are mainly associated with the basic theory of sustainability and are primarily linked to our targeted constructs of SSP (product development, long-term relations, quality-focused, and reduced supplier base). Researchers have also adopted these constructs to measure SSP (Thomas et al. 2016; Qazi et al. 2022; Schulze et al. 2022; Rahman et al. 2023). This study primarily examines the impact of various OM on SSP, specifically in the existence of stakeholder pressure by highlighting the role of organizational size. These pressures exert a significant effect on the embracing of SSP. The study model depicted in Fig. 1 illustrates the relationships between OM (IM, RM, and MM) and SSP, contemplating the moderating role of STP and organizational size.

2.2 Sustainable sourcing practices (SSP)

Rapid industrialization has given rise to the importance of sustainability and sustainable sourcing (Foo et al. 2018). Preceding research found that 3000 enterprises globally contributed over USD 2 trillion in environmental concerns yearly which adversely impact business sustainability (Shahzad et al. 2022a; Foo et al. 2018). The concept of sustainable and green sourcing in the supply chain has emerged as a driver for companies to reduce costs, gain a competitive advantage, and enhance financial performance by increasing efficiency, particularly in competitive markets within emerging countries (Thomas et al. 2016; Bueno-Garcia et al. 2021). On the contrary, concerns about environmental safety, openness in business operations, security challenges, and labor welfare necessitate that corporations modify their raw material procurement methods accordingly (Dai et al. 2021; Schulze et al. 2022). To achieve sustainability throughout the sourcing process, companies must prioritize environmentally-friendly products and adopt a green management approach that aligns with legal regulations and activist initiatives, rather than solely focusing on financial performance (Shahzad et al. 2020c). Visionary firms have already begun implementing green and sustainable sourcing practices for green supply chain management, aiming to attain long-standing benefits from SD (Schulze et al. 2022; Rehman et al. 2023). Prior researchers also highlighted and acknowledged the critical role of the IOT, industry 4.0, and sustainability-oriented innovation in enhancing green growth and sustainability outcomes (Ahmed et al. 2021; Kalsoom et al. 2021; Ferrari et al. 2023). Besides, organizational strategy and environmental CSR with the adoption of blockchain technology also affect green technology innovation for sustainable performance (Shin et al. 2000; Akbari and Hopkins 2022; Sun et al. 2022).

Earlier SD and business ethics research has consistently found that OM are crucial in driving corporations to adopt green and sustainable sourcing (Paulraj et al. 2017; Del Giudice et al. 2020). While they constantly move towards reducing costs and enhancing production capacity, they also raise risks; such as the risk of choosing non-sustainable materials over sustainable alternatives due to price disparities (Rogetzer et al. 2018). Alternatively, consumers, employees, and other organizational stakeholders are beginning to question these goods’ source and manner of production. Consumers are now prepared to pay more for sustainable products to combat ecological degradation (Chen 2008; Mungkung et al. 2021). Due to stakeholders’ demands, organizations commit to accountability for their sourcing environmental and social impacts. Sustainable procurement is rising due to its economic, ecological, and social benefits; many organizations recognize the benefits of a green supply chain (Gu et al. 2014; Del Giudice et al. 2020). Pursuing ST, Shahzad et al. (2020b) emphasized that STP significantly positively influences CSR and green innovation through effective knowledge management. Further, STP also affects green management practices directly and indirectly through OM (Shahzad et al. 2022a). In addition, Rehman et al. (2023) realize that corporate motives significantly impact the adoption of SSP.

Following the previous research, SSP encompass integrating social, environmental, and economic fundamentals into a firm’s procurement processes, going beyond the standard delivery, pricing, and quality contemplations (Dai et al. 2021; Rehman et al. 2023). It involves several key elements including supplier verification and certification in compliance with environmental legislation to enhance product quality. It also entails green purchasing, emphasizing utilizing renewable energy to produce environmentally-friendly goods. Additionally, establishing long-term buyer-supplier partnerships is crucial to foster synchronization and collaboration between buyers and suppliers to pursue sustainability goals (Schulze et al. 2022).

2.3 Organizational motives (OM)

A motive is an implied desire or emotion influencing an individual’s ambition that causes him/her to act (Paulraj et al. 2017). Motivation can be further divided into extrinsic and intrinsic aspects of motivation from the many things that motivate people. Intrinsic motivation encompasses all internal motivators such as self-actualization or assisting a friend in need. Extrinsic motivations are behavior driven solely by external rewards such as money, grades, praise, or fame (Reiss 2012). To be motivated means to be moved into action. The equity theory postulates that organizations will weigh their input into an initiative against the output they receive from it (Reiss 2012). While previous researchers identified many reasons to take the initiative, three manifest motives, namely “instrumental motives (IM), relational motives (RM), and moral motives (MM)”, move a firm to adopt sustainable practices (Paulraj et al. 2017). We mainly adopted these three distinct motives for adopting SSP for this work.

IM refer to motives governing employee and company self-interests (Qin et al. 2018; Shahzad et al. 2022a). Within the framework of SSP, IM refer to the convenience or inconvenience associated with implementing sustainable sourcing strategies. They include reducing environmental impact, enhancing brand reputation, increasing revenue, fostering stronger stakeholder partnerships, and improving risk management (Paulraj et al. 2017). Organizations adopt sustainable methods to boost their brand image and IM profits. RM seek social legitimacy (Rousseau and Tijoriwala 1999; Shahzad et al. 2022a).

In conformity with legitimacy theory, a business will undertake activities willingly if top management believes that such actions are required by the communities in which it functions for sustainable practices (Amjad et al. 2017). RM signify that organizations can effectively communicate their social and competitive positioning by adopting sustainable sourcing practices. By doing so, they can associate their green sourcing efforts with those of others and align them with social norms and expectations. Prouteau and Wolff (2008) proposed that RM can enhance networking opportunities by actively engaging in CSR activities within the local community. Furthermore, virtue and ethics lead to MM. MM motivate organizations to embrace sustainable and green practices without internal or external pressure, going beyond compliance with environmental regulations (Chang 2019; Shahzad et al. 2022a). These emotions, often associated with being sustainable, can be seen as a sense of pride arising from competitiveness. Hypothetically, these emotions can precede the decision-making process when making production choices in favor of sustainability.

2.4 Hypotheses development

2.4.1 Instrumental motives (IM)

The impact of IM on SSP is undeniable and irrefutable. Organizational reactions to environmental and social concerns have been studied using instrumental perception, i.e., what compensations a corporation might obtain by addressing social issues (Qin et al. 2018; Shahzad et al. 2022b). STP scholars found that synchronizing organizational value development with IM to increase shareholders’ long-term value makes businesses more inclined to be engrossed in socially responsible activities (Shahzad et al. 2020b). Managers should consider enhancing compensation packages to mitigate a negative reputation and improve a firm’s competitiveness and profitability (Paulraj et al. 2017).

Preceding research has recognized that the positive outcomes associated with SSP inspire top management commitment to espouse and adhere to these green practices (Qin et al. 2021; Rahman et al. 2023). By designing and manufacturing products and processes following environmental standards, firms can reduce costs by eliminating resource waste. Besides, SSP inspire shareholders to invest more, enhance staff morale, and promote unity (Rogetzer et al. 2018). In the current intense competition, organizations strive to attain sustainable competitiveness. To achieve this, every organization must collaborate with contractors and customers to reach instrumental outcomes. Effective exterior alliances must incorporate sustainability into manufacturing operations, resulting in financial benefits (Bansal and Clelland 2004). IM are vital to gain the returns of SD (Gao and Bansal 2013). The instrumental approach to sustainability primarily focuses on economic considerations and often fails to fully integrate social and ecological apprehensions into organizational operations. Therefore, it only addresses a subgroup of the broader sustainability archetype. Ethical egoism theory views IM as a significant driving force behind an organization adopting SSP. Following the same vein, the hypothesis below is proposed:

H1

Instrumental Motives (IM) significantly impact Sustainable Sourcing Practices (SSP).

2.4.2 Relational motives (RM)

Relational motivation exemplifies corporate principles and objectives that explicitly conflict with instrumental encouragements, which are aligned with utilitarianism theory (Paulraj et al. 2017). RM elucidate observations like SSP that may be seen in ST. It is appealing to investigate “why prominent businesses have embraced SSP” and RM are a vital component that will be evaluated to analyze the implications of this adjustment (Prouteau and Wolff 2008; Gu et al. 2014). RM reflect the overall payback to all stakeholders involved in commercial activity, aiming to promote competitiveness and sustainability (Rehman et al. 2023).

ST represents variety by focusing on stakeholder well-being and shareholders’ interests. Legitimacy and utilitarianism theory also help identify that if a business legitimately follows the norms of stakeholders and ethical egoism, an organization has the RM to adopt SSP (Aguilera et al. 2007; Rehman et al. 2023). Instead of targeting short-term shareholder profits, enterprises can emphasize the reprieve of numerous stakeholders such as delivering ecologically friendly goods to customers, suppliers reducing harmful materials, and personnel co-ordinating ecological training and awareness programs (Aguilera et al. 2007).

Prior studies have shown that for businesses to survive, it is obligatory to imitate the successful movements of their contestants in order to outperform them (Hofer et al. 2012). Moreover, organizational CSR is the primary reason for developing a competitive ecological strategy (Shahzad et al. 2019; Yousaf 2021; Rehman et al. 2023). The strategical differences can lead to sustainable competition according to the client’s necessities and feedback. Diverse scholars have extolled customers’ sustainability concerns (Shahzad et al. 2022a). Business activities are inherently relational, as the entire value chain relies on the collaboration and interaction between manufacturers, suppliers, the government, and customers. It also covers social, ecological, and economic structure interrelationships (Del Giudice et al. 2020; Rahman et al. 2023). Subsequently, we offer the succeeding hypothesis after evaluating competitive forces and stakeholder interests:

H2

Relational Motives (RM) significantly impact Sustainable Sourcing Practices (SSP).

2.4.3 Moral motives (MM)

MM are ethical standards, honesty, and moral belief. Morally-driven businesses are more likely to accept, support, and promote SD. Such organizational moral obligation pushes them to constructively serve nature and society to boost the forthcoming generation (Chang 2019). An organization with MM has the moral responsibility of positively influencing the economy, society, and environment, providing light on the future (Chen and Kitsis 2017; Shahzad et al. 2022a). Managers play a crucial role in integrating sustainable and environmentally-friendly practices into business plans by taking actions guided by environmental considerations (Chen and Kitsis 2017). Organizations incorporate CSR initiatives into their strategies to drive societal change through their commitment to responsible stewardship. These initiatives prioritize social and ethical actions to foster a healthier, more sustainable society (Prouteau and Wolff 2008). Previous examination has emphasized the importance of MM as a crucial factor beyond mere compliance with laws and regulations to foster a better future (Chang 2019). Besides, experimental studies have shown that MM play a prominent role in driving and persuading green practices (Paulraj et al. 2017).

MM facilitate the improvement of top management commitments and reinforce association and capacities with channel stakeholders (Cantor et al. 2014). Scholars of organizational virtuousness also recommended that firms with good repute are more engaged in SSP as they consider it the right path to follow (Chen and Kitsis 2017). Past study has shown that a corporation with MM is morally accountable for making beneficial economic, environmental, and social deviations by implementing sustainable practices (Morais and Silvestre 2018). Further, the morality-based values of managers motivate them to think beyond financial benefits. When managers consider stewardship theory by showing concern for environmental issues and behaving accordingly by initiating MM’s actions for a healthier civilization, they inoculate the SSP into their corporate strategies (Cantor et al. 2014). These preceding studies and findings suggest MM and SSP are related, motivating an organization to examine environmental concerns and do the “right thing.“ So, we can hypothesize:

H3

Moral Motives (MM) significantly impact Sustainable Sourcing Practices (SSP).

2.5 Stakeholders’ pressure and organizational motives

OM are essential elements that entitle a company to respond to stakeholder claims for participation in a green and sustainable future (Shahzad et al. 2022a). ST has stated diversified STP might motivate use of OM to explore anti-environmental concerns and use of eco-friendly solutions for growth (Rehman et al. 2023). It is pronounced as “the ability and capacity of stakeholders to affect an organization by influencing its decisions” (Helmig et al. 2016). Humankind is facing environmental, socio-economic, and resource issues. Rising awareness and corporate objectives make sustainable and green activities prominent topics (Lee et al. 2018).

Preceding studies have recognized several drivers of OM including management strategies, organizational structure, external customers, competitors, and corporate employees. These factors shape organizations’ motives and behaviors (Yu and Choi 2016; Yousaf 2021). STP and top management commitment are key aspects that motivate organizations to adopt environmental strategies as essential green practices. These factors are crucial in implementing environmentally-friendly organizational initiatives (Shahzad et al. 2022a). Further, pursuant to Helmig et al. (2016), stakeholders have a significant influence on environmental and social responsibilities. Likewise, Shahzad et al. (2020b) emphasized that STP greatly drives green innovation and CSR. Furthermore, these activities are the basis for gaining a competitive advantage, fostering environmental sustainability, and achieving SD outcomes (Del Giudice et al. 2020). Earlier research has also revealed that competitive pressure, external and internal STP, organizational support, and institutional pressure are critical to achieving SSP. These factors are vital in shaping sustainable sourcing initiatives within organizations (Lee et al. 2018; Yousaf 2021; Rahman et al. 2023).

Organizations may be reluctant to adopt environmentally-friendly practices without stakeholder pressure, leading to subpar environmental and economic performance. STP drives organizations to prioritize sustainability and implement effective environmental practices (Shahzad et al. 2022a). Rehman et al. (2023) exposed that regulatory pressure positively influenced the realization of SSP. Further, media and NGO pressures have driven companies to share evidence about their production, ensuring accountability and gaining customer trust, thereby contributing to SSP adoption (Albort-Morant et al. 2018; Ambekar et al. 2019). In response to STP, dynamic companies adopt eco-friendly activities and leverage predominant and recently acquired information in their research and development (R&D) efforts to mature novel processes and advanced technologies to minimize ecological damage (Yousaf 2021). Also, sustainability can be employed to achieve green business goals encompassing environmental, economic, and social sustainability (Rehman et al. 2023). Following the above argument, the subsequent hypotheses are proposed:

H4

Stakeholder Pressure (STP) moderates the relationship between OM (IM - H4a, RM - H4b, MM - H4c) and Sustainable Sourcing Practices (SSP).

2.6 Moderation of organizational size

In most contexts, “organizational size” denotes the total number of staff members in a particular geographic area. Several academics have shown that specific characteristics of organizations are associated with a higher likelihood of adopting environmentally friendly and sustainable practices (Shahzad et al. 2022b). Following prior research findings, this investigation considers the magnitude of the organization size as a moderating variable (Shu et al. 2016; Ma et al. 2018; Shahzad et al. 2022b). Lin and Ho (2008) stressed the importance of organizational resources, particularly the quality of resources and organizational size, as an additional factor influencing the adoption of SSP. Besides, Lin et al. (2020) emphasized the standing of corporate resources in determining the degree to which green sourcing is adopted. Adopting environmentally-friendly sourcing is one way organizations execute creative environmental strategies. An organizational capacity for adopting innovative technologies is increased when it possesses more resources and a larger size. Consequently, the following hypothesis is put forward for consideration:

H5

H5: Organizational size significantly moderates the abovementioned relations towards SSP in confounding ways.

3 Research methods

3.1 Sample and procedure

The current study’s target populace is manufacturing businesses with ISO certifications such as 9001 and 14,001 and listed on the “Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX)”. This research collected data by email and personal visits from August 2021 to March 2022. Because of the Covid-19 outbreak, we connected with upper, medium, and lower-level staff members that have detailed evidence of organizational policies. Participants were asked to complete a survey on OM and their impact on their capacity to source sustainably; responses were verified on a 7-point Likert scale. We received 308 operational responses from a total of 740 surveys issued, with a response ratio of 42%. The preponderance of informants, 43%, supervised organizational policy implementation. Table 1 displays the comprehensive demographic results. The 10X principle was applied for sample volumes, “10 times the largest number of structural paths directed at a particular latent construct in a structural model”, as proposed by Hair et al. (2017).

3.2 Measures and validation

The study questionnaire was segregated into three sections by the researcher. The four fundamentals linked to diverse aspects of SSP (Shin et al. 2000) were employed in the first section, which were quality emphasis in choosing suppliers, long-term buyer-supplier relations, supplier participation in product development, and reduced supplier base. Second section covers nine measures that were implemented for different OM, i.e., three measurements were used to quantify IM by Bansal and Clelland (2004) and Paulraj et al. (2017), three measures were used to quantify RM by Buysse and Verbeke (2003) and Paulraj et al. (2017), and three measures were served to quantify MM by Paulraj et al. (2017). These elements measured the level to which organizations are involved in SSP to satisfy the demand for sustainability and profitability enhancement, surge in customer base, meet sustainability guidelines, distinguish from competitors to gain a competitive edge, genuine concern and sense of obligation for the environment, and top management trust. In the third section, the STP was separated into two constructs: government/regulatory measures with three items and NGOs/activists also measured through three measures espoused from the research of Helmig et al. (2016). These elements measured the organizational presence and media monitoring to establish collaborations with relevant NGOs to improve sustainability and long-term environmental growth objectives. Measures were valued employing a 7-point Likert scale. 7 facilitates “strongly agree” and 1 facilitates “strongly disagree”. A 7-point scale is easier to use, more precise, and represents a respondent’s objective assessment compared to a 5 point scale. Further, a 7-point scale is best for evaluating questionnaire survey (Finstad 2010). Subsequent to Hinkin’s (1998) confirmation, we led a pilot survey to prove reliability and validity.

4 Data analysis and results

We used PLS-SEM to investigate the connections of OM, SSP, and STP. Because PLS-SEM is ideal for exploratory research (Hair et al. 2017), concurrent processing of measurement and structural models is also possible in PLS-SEM. More accurate estimations can accommodate small sample volumes (Hair et al. 2017). Thus, for this study, the academics employed SmartPLS ver 3.3.7.

4.1 Common method variance bias

Common method bias (CMB) may alter format content and element responsiveness, leading to inaccurate measurements (Podsakoff et al. 2012). We utilized a first factor test to inspect the CMB using a non-rotating method (Harman 1976). The outcomes showed that no sole element was reported for more than 33.60% of the variation; hence, this research has no significant CMB problem (Harman 1976). Respondents were asked to fill out the survey honestly. This study also used the efficient approach suggested by Kock (2015). A full collinearity analysis was executed to calculate the inflation rate (VIF). All VIF values were below 3.3. Consequently, based on the available evidence, it can be inferred that CMB is not an anxiety in this study.

4.2 Analysis of the measurement model

The measurement model was assessed using construct reliability measures such as (“Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, composite reliability”) and validity measures including (“convergence and discriminant validity”) pursuing the guidelines recommended by Hair et al. (2017). Reliability was assessed by “Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR)” values. The findings indicated that the values of CR and CA were greater than the least threshold value, signifying good reliability of the measurement model (Cohen 1988; Hair et al. 2017). Besides, all the factor loadings and AVE standards exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.50, as specified by Hair et al. (2017). The comprehensive results with assessment criteria are imparted in Tables 2 and 3.

The Fornell-Larcker approach was applied in this study to assess the discriminant validity (DV) of the measurement models (Fornell and Larcker 1981) and the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) method (Henseler et al. 2015). In line with the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square root of the AVE for each construct should exceed the connection between the constructs to establish DV. Sarstedt et al. (2017) recommended 0.85 scores for DV in the case of HTMT. The resultants are presented in Table 4 support both criteria, demonstrating that the measurement models are valid and robust for evaluating the proposed structural model.

4.3 Analysis of the structural model

Pursuing the authentication of the measurement model, the structural model was tested to assess the validity of the proposed hypotheses using the bootstrap method with 5000 resamples. The consequences of the model exposed substantial and positive influence of IM on SSP (H1: β = 0.234; p < 0.006), RM (H2: β = 0.239; p < 0.005), MM (H3: β = 0.165; p < 0.046), which confirm hypotheses H1 to H3. None of the control variables yielded substantial results. The complete results of the hypothesis testing, including the β and corresponding p-values, are presented in Table 5.

4.4 Moderation analysis

The research also explores the role of STP as a moderator in the relationship between various OM (IM, RM, MM) to SSP. The results, depicted in Table 5, demonstrate that STP has a substantial moderating effectuate on the association between IM and SSP, with a p-value of 0.05 (β = 0.139; p < 0.012), as well as between MM and SSP, with a p-value of 0.05 (β = 0.109; p < 0.046). Consequently, hypotheses H4a and H4c are supported, indicating that STP plays a significant role in moderating the impact of IM and MM on SSP. However, STP regulates the relationship between RM and SSP at a p-value of 0.10 (β = 0.094; p < 0.090), accepting hypothesis H4b. The significant effects of these relationships are visually represented in Figs. 2, 3 and 4. These figures illustrated the slopes of interaction effects. When managers or policymakers face higher pressure from stakeholders than lower pressure, SSP adoption in the manufacturing industry will improve. The middle line in the graph highlights the mean values and the upper and lower lines show the standard deviation at + 1 and − 1.

Moreover, the multi-group analysis (MGA) was conducted to observe the moderation effect of organizational size. MGA is valuable in assessing significant differences between multiple groups within the data, particularly when a categorical moderator is intricate in the model (Hair et al. 2017). Data were alienated into two groups by employee count to measure the moderation of organizational size: 1 to 200 (small, n = 135) and 200+ (large, n = 173). Table 5 displays the findings of MGA. MM considerably affected SSP in smaller organizations, while IM and RM had insignificant effects. For larger organizations, all effects were significant. These results recommended that the inclination for SSP among these clusters has incongruities (larger to smaller). Smaller organizations have inadequate resources and investment capacities, unlike large-size organizations. Hence, H5 is supported.

4.5 Assessment of R2, F2, and Q2

The R2 and F2 were also evaluated. Our findings revealed that the overall model explained a 35.2% variance in SSP before the inclusion of the moderator and 38.4% with the moderator, indicating good predictive power. Similarly, we assessed Q2 values using a blindfolded procedure to measure predictive accuracy. Hair et al. (2017) specified that the model is predictive when Q2 > 0. Our finding revealed that Q2 of SSP before the inclusion of the moderator is 0.210 and 0.216 with the moderator. These results show that our model has decent predictive relevance. Besides, we employed Cohen’s (1988) trials to confirm F2. The F2 values for IM, RM, MM, and STP were 0.039, 0.033, 0.017, and 0.004, respectively. Further, we weighed the model fit through the “standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR)”, where a recommended threshold value is < 0.08 (Hair et al. 2017). Our SRMR score is 0.056, suggesting our model demonstrates a good fit. We also assessed the model fit by (GOF = √ (AVE × R2) following Wetzels et al. (2009). In this study, GOF is 0.51, signifying that the model fit satisfies the large criterion.

4.6 Importance-performance map analysis (IPMA)

When it comes to the graphical depiction of path coefficients, IPMA is a well-regarded instrument (Hair et al. 2017). The results in Fig. 5 demonstrate the constructs’ comparative performance and importance values. The importance and performance values for IM, RM, MM, and STP are (0.174, 67.515), (0.201, 70.694), (0.128, 71.833), and (0.041, 71.552), respectively, in SSP predictions. Additionally, the performance value for MM (71.833) is relatively higher than all other exogenous constructs, while the importance value for RM (0.201) is relatively higher among the constructs.

5 Discussion on key outcomes

This study incorporates ST to develop a theoretical framework that explores the relationship among OM, SSP, and STP. Data for this research comprised manufacturing companies in Pakistan to assess the proposed hypotheses. According to the empirical research findings, IM, RM, and MM prompted green sourcing and encouraged firms to devise SSP in response to demand from various stakeholders. To accomplish the purpose of the research, we put forward five main hypotheses. In certain manufacturing industries, sustainable and green practices may be new ideas and their effectiveness may be unknown. The findings indicate that IM positively contributes to SSP with β = 0.234, endorsing H1. Similarly, RM hugely influence SSP with β = 0.239, endorsing H2. Moreover, MM also significantly influence SSP with β = 0.165, endorsing H3. Largely, these results followed Amjad et al. (2017); Paulraj et al. (2017); Rehman et al. (2023); Shahzad et al. (2022a); Sun et al. (2022) who recognized similar outcomes in this setting. Besides, Gao and Bansal (2013) documented the essence of IM to gain profits from sustainable growth. RM were crucial in fostering comprehensive stakeholder relationships to preserve natural and economic structures (Touboulic and Walker 2016). A firm contributes to SSP if it produces eco-friendly products using best practices without sacrificing supplier interests. This supports earlier studies by Shahzad et al. (2022a), who recognized the positive connection between MM and green management practices. Modifying firms’ strategies based on OM and customer necessities can vastly enhance the acceptance of SSP among organizations, resulting in competitive advantages. Moreover, due to MM, organizations are inclined to fulfill their ethical duties and perceive them as their moral commitment and responsibility, which certainly impacts society and the environment. The progress of an ecological strategy in a competitive environment is primarily driven by the organization’s ethical and socially responsible actions (Gao and Bansal 2013). The competitive strategies in the environmental domain, supported by MM, can effectively mitigate ecological issues and generate greater satisfaction and constructive response from numerous stakeholders.

Besides, the moderating impact of STP was suggestively endorsing H4a-b-c with β = 0.139, 0.094, and 0.109, respectively. These substantial outcomes align with preceding studies by Albort-Morant et al. (2018); Shahzad et al. 2020a); Rehman et al. (2023). Our study makes a significant offering to the existing literature by thoroughly considering and highlighting the pacifying role of STP among IM, RM, MM, and SSP. These results predominantly exposed regulatory and NGO pressure’s significant role in realizing SD objectives by signifying SSP. Finally, this study used MGA to examine how organizational size moderates integrated relationships. By accepting H5, organizational size affects structural relations differently, which is intriguing. Implementing SSP and greening production operations can be time-consuming and costly, making it challenging for every organization to adopt. However, larger organizations have an advantage in this regard, as they can leverage economies of scale to implement SSP effectively by expanding their output levels (Shahzad et al. 2022b). Concisely, the inclusive outcomes of this study offer substantially to the prevailing body of literature and provide new insights into SSP, highlighting the importance of the relationships among suppliers, distributors, government, and the interests of various stockholders. These findings enhance our understanding of SSP and its multifaceted nature. It is also evident from preceding studies that STP has increased the espousal of green and sustainable sourcing, which ultimately supports the global phenomenon of a sustainable future in European and developed countries (Meixell and Luoma 2015; Haque and Ntim 2022; Siems et al. 2022). Further, implementing EU environmental laws safeguards natural ecosystems, clean air, and water, ensures waste disposal, increases understanding of harmful chemicals, and enables enterprises to transition to a sustainable economy (Haque and Ntim 2022), which is the need of the current global era. Developing countries should follow stringent environmental laws and policies for green resource delivery. This research also provides support for the multinational manufacturing organization to adopt SSP backed by organizational core motives, organizational size, and STP that facilitates the significance of green industrialization in the international market.

6 Conclusion and research contributions

6.1 Conclusion

This research has made significant contributions by presenting novel propositions to expand the existing literature. The study aimed to examine the influence of various OM (IM, RM, and MM) on SSP in the context of STP and organizational size subsequent ST in the Pakistani manufacturing industry. The projected framework was tested using SEM grounded on prior literature. The experiential analysis exposed that each of the OM, such as IM, RM, and MM, has a direct impact on SSP. Moreover, STP notably moderated the relationship between each motive and SSP. These outcomes contribute to a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics between OM, STP, and SSP. Organizational size also curbs the aptitude to pursue SSP differentially in small and large organizations. The IPMA also recognizes the significance of all the constructs examined in this study. Embracing SSP involves aligning the corporate vision with OM under the influence of STP. Notably, the performance of MM and the importance of RM surpassed that of other constructs in the IPMA framework, highlighting the compelling case for embracing SSP based on moral principles. Moreover, this research presents concrete evidence that ethical and social accountability are crucial in environmentally-conscious, sustainable, and eco-friendly management approaches. The outcomes of this study hold promise as a reference point for guiding future progress and the effective adoption of SSP.

6.2 Theoretical implications

The current study contributes considerably to the expanding body of work on OM, STP, and SSP theoretically. Firstly, this research categorizes the model grounded on ST to expand the existing body of literature in the Pakistani manufacturing industry. This research provides empirical support for the tenets of ST, highlighting that organizations are increasingly influenced by stakeholder demands when making sourcing decisions. Secondly, the research sheds light on the significant role of OM in driving SSP. Organizations prioritizing ecological and social impacts in their supply chain decisions will likely align with the increasing demand for sustainable products and services. The research outcomes illuminate the complex interconnections between all the direct relationships examined in this study. Besides, the moderated model explains the link between each construct (IM, RM, MM, and SSP) with the moderation of STP among these targeted relationships, which is a novel marvel and has previously not been assessed. This research supplements the prior literature by indicating that these three OM are vital for SSP’s embryonic activities. Third, the study underscores the long-term benefits associated with SSP. Organizations that recognize the economic, ecological, and social advantages of green supply chains are more likely to be competitive in a changing business landscape. Fourthly, IPMA has elevated the importance and performance of each construct. Contrary to Rehman et al. (2023), this research divulges that each motive has a varying influence on SSP implementation. Specifically, the MM scored the highest performance at 71.552, while the RM scored the highest importance at 0.201, surpassing other constructs in the IPMA framework. These findings emphasize the decisive argument for adopting SSP based on moral principles. Prior research highlighted that regulatory pressure was more important in this context.

Paulraj et al.‘s (2017) highlighted that OM undergo development and refinement over time, and a higher level of motivation results in improved effectiveness in achieving sustainability and ecological stability. The results also shed light on the implications of adopting green tactics, as OM plays a substantial role in driving the implementation of SSP within industries aligned with the UN sustainable agendas. According to Shahzad et al. (2022a), including SSP and ecological factors in the operations of industrial sourcing may help accomplish sustainable goals, boost market value, preserve energy, and reduce emissions. Larger organizations are more inclined to adopt green and sustainable practices quicker than medium and small-sized organizations because green sourcing impacts green manufacturing and delivery (Shahzad et al. 2022b). Having ample financial and non-financial resources, these organizations have an advantage and could become the market leader in adopting sustainable practices. Smaller and less resourceful organizations should follow in the footsteps of larger organizations to compete in the global market. Further, industries with multifaceted aspirations and preferences can also use it to boost SSP efficiency by accumulating adoption across operations. It is the only way to compete globally and avoid global ecological and sustainability risks in the current scenario.

6.3 Practical implications

This research offers practical recommendations for regulators, executives, and policymakers. One of the primary takeaways from this research is that businesses should work toward aligning the core motives to implement sustainable objectives throughout the organization to boost their day-to-day operational competitiveness. As sustainability becomes an increasingly critical aspect of business operations, companies should stay updated with evolving regulations and industry standards related to sustainable sourcing (Jin et al. 2022). Adapting to these changes can help organizations remain compliant and maintain a competitive edge. Further, a genuine commitment to sustainability can be a powerful driving force for implementing green sourcing strategies and are more likely to maintain competitiveness in a dynamic business environment. Hence, stakeholders are urged to integrate OM into their sustainability policies and action plans. This step ensures the coherence and efficacy of their SSP and enables them to monitor the outcomes achieved through these initiatives. Secondly, this research offers valuable insights into the stimulation of SSP by analyzing the influence of three key motives, thereby contributing to organizational sustainability. Organizations can benefit from sharing best practices and collaborating with other industry players to advance sustainable sourcing initiatives. Furthermore, our IPMA outcomes also revealed the relative significance of STP and each OM (IM, RM, MM ) for SSP. MM are more crucial for SSP, thus highlighting the importance of moral responsibility in sustainable sourcing. Organizations should embrace ethical principles and values to foster a culture of responsible sourcing and positive societal contributions. Moreover, the strategic link between SSP and OM is crucial in fully representing SD as it enables organizations to effectively achieve the outcomes of practices and avoid potential threats to sustainable processes. Following international standards and stringent laws also supports sustainable sourcing. Consequently, policymakers and senior management should cautiously plan and implement sustainable practices vital to firms’ competitiveness and excellence (Maasoumi et al. 2020). Besides, implementing SSP may require more time and greater financial resources. The size of an organization plays a crucial role in determining its available resources and, consequently, its impact on organizational sustainability. As evident from our moderation results, larger organizations often have more substantial financial, technological, and human resources. They have greater green investment capacity, scalability of sustainable practices, and R&D opportunities. Thus, they can easily adopt a long-term perspective, incorporating sustainability goals into their strategic planning and allocating adequate resources to support sustainability initiatives.

Further, in the Asian region, stakeholders, especially buyers, are becoming more aware of environmental and ecological laws and policies through social media. Corporations in this region lack the ingenuities to achieve trust and social capital (Shahzad et al. 2020b). Top leadership motives should align with regulatory bodies and move forward with a shared goal for a greener future. The moderation results show that STP can make an organization more likely to adopt SSP when OM are in play. Most likely, failing manufacturing industries worldwide are due to conventional manufacturing, lack of innovation, and adverse environmental effects. This will require regulators and stakeholders to employ stringent corrective measures and techniques for monitoring their operations instead of perimeter methods. Organizations in developing nations should follow in the footsteps of industrialized countries to enhance the embracing of green and sustainable sourcing. This study holds great significance as it offers a valuable understanding of the crucial enactment of sustainable innovation processes that maximize SD. Consequently, it plays a pivotal role in transmuting the manufacturing sector of emerging nations and making substantial contributions to national economic growth.

6.4 Future research

Despite the research’s enormous significance, it is essential to understand its shortcomings, which may affect future research. For this study, data from manufacturing companies in Pakistan were sampled exclusively to focus on the context of the Pakistani manufacturing industry. In the future, researchers can expand their data collection efforts to encompass various industries and domains, allowing for a more comprehensive application of this approach. Though integrated practices of SSP are considered following the notable published studies related to the manufacturing industry. Future scholars could propose different groups of constructs based on the existing practices of sustainable sourcing (Ambekar et al. 2019) to address this phenomenon according to the prevailing industries. Besides, scholars can attempt to compare these different constructs’ applications in various industries to understand sustainable sourcing better.

References

Abdul S, Khan R, Zahid A, Zhang P (2022) Digital technology and circular economy practices: future of supply chains. Oper Manag Res 15:676–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-021-00247-3

Aguilera RV, Rupp DE, Williams CA, Ganapathi J (2007) Putting the s back in corporate social responsibility: a multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad Manag Rev 22:836–868. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.25275678

Ahmed S, Kalsoom T, Ramzan N et al (2021) Towards supply chain visibility using internet of things: a dyadic analysis review. Sensors 21:1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21124158

Akbari M, Hopkins JL (2022) Digital technologies as enablers of supply chain sustainability in an emerging economy. Oper Manag Res 15:689–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-021-00226-8

Albort-Morant G, Leal-Rodríguez AL, De Marchi V (2018) Absorptive capacity and relationship learning mechanisms as complementary drivers of green innovation performance. J Knowl Manag 22:432–452. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-07-2017-0310

Ambekar S, Kapoor R, Prakash A, Patyal VS (2019) Motives, processes and practices of sustainable sourcing: a literature review. J Glob Oper Strateg Sourc 12:2–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGOSS-11-2017-0046

Amjad M, Jamil A, Ehsan A (2017) The impact of organizational motives on their performance with mediating effect of sustainable supply chain management. Int J Bus Soc 18:585–602

Awan U, Kraslawski A, Huiskonen J (2017) Understanding the relationship between Stakeholder pressure and sustainability performance in Manufacturing Firms in Pakistan. Procedia Manuf 11:768–777

Baah C, Opoku-Agyeman D, Acquah ISK et al (2021) Examining the correlations between stakeholder pressures, green production practices, firm reputation, environmental and financial performance: evidence from manufacturing SMEs. Sustain Prod Consum 27:100–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2020.10.015

Bansal P, Clelland I (2004) Talking trash: legitimacy, impression management, and unsystematic risk in the context of the natural environment. Acad Manag J 47:93–103. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159562

Bueno-Garcia M, Ortiz‐Perez A, Mellado‐Garcia E (2021) Shareholders’ environmental profile and its impact on firm’s environmental proactivity: an institutional approach. Bus Strateg Environ 30:374–387

Bui TD, Tsai FM, Tseng ML et al (2021) Sustainable supply chain management towards disruption and organizational ambidexterity: a data driven analysis. Sustain Prod Consum 26:373–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2020.09.017

Buysse K, Verbeke A (2003) Proactive environmental strategies: a stakeholder management perspective. Strateg Manag J 24:453–470. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.299

Cantor DE, Blackhurst J, Pan M, Crum M (2014) Examining the role of stakeholder pressure and knowledge management on supply chain risk and demand responsiveness. Int J Logist Manag 25:202–223

Chang CH (2019) Do green motives influence green product innovation? The mediating role of green value co-creation. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 26:330–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1685

Chatterjee S, Chaudhuri R (2021) Supply chain sustainability during turbulent environment: examining the role of firm capabilities and government regulation. Oper Manag Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-021-00203-1

Chen Y-S (2008) The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. J Bus ethics 81:531–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9522-1

Chen IJ, Kitsis AM (2017) A research framework of sustainable supply chain management: the role of relational capabilities in driving performance. Int J Logist Manag 28:1454–1478. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-11-2016-0265

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers

Dai J, Xie L, Chu Z (2021) Developing sustainable supply chain management: the interplay of institutional pressures and sustainability capabilities. Sustain Prod Consum 28:254–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.04.017

Del Giudice M, Chierici R, Mazzucchelli A, Fiano F (2020) Supply chain management in the era of circular economy: the moderating effect of big data. Int J Logist Manag 32:337–356. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-03-2020-0119

Ding X, Qu Y, Shahzad M (2019) The impact of environmental administrative penalties on the disclosure of environmental information. Sustain 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205820

Ferrari A, Mangano G, Corinna A, Alberto C (2023) 4.0 technologies in city logistics: an empirical investigation of contextual factors. Oper Manag Res 16:345–362

Finstad K (2010) Response interpolation and scale sensitivity: evidence against 5-point scales. J Usability Stud 5:104–110

Foo PY, Lee VH, Tan GWH, Ooi KB (2018) A gateway to realising sustainability performance via green supply chain management practices: a PLS-ANN approach. Expert Syst Appl 107:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2018.04.013

Fornell C, Larcker D (1981) Evaluating Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18:39–50

Freeman RE (1984) Strategic Management: a Stakeholder Approach. Pitman Press, Boston

Gao J, Bansal P (2013) Instrumental and integrative logics in business sustainability. J Bus Ethics 112:241–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1245-2

Gu VC, Hoffman JJ, Cao Q, Schniederjans MJ (2014) The effects of organizational culture and environmental pressures on IT project performance: a moderation perspective. Int J Proj Manag 32:1170–1181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.12.003

Hair JFJ, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2017) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd edn. Sage publications

Haque F, Ntim CG (2022) Do corporate sustainability initiatives improve corporate carbon performance? Evidence from european firms. Bus Strateg Environ 31:3318–3334. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3078

Harman HH (1976) Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA

Helmig B, Spraul K, Ingenhoff D (2016) Under positive pressure: how Stakeholder pressure affects corporate social responsibility implementation. Bus Soc 55:151–187

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43:115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hinkin TR (1998) A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organ Res Methods 1:104–121

Hofer C, Cantor DE, Dai J (2012) The competitive determinants of a firm’s environmental management activities: evidence from US manufacturing industries. J Oper Manag 30:69–84. https://doi.org/0.1016/j.jom.2011.06.002

Jaafar H, Razi NA, Azzeri A et al (2018) A systematic review of financial implications of air pollution on health in Asia. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25:30009–30020

Jin C, Shahzad M, Zafar AU, Suki NM (2022) Socio-economic and environmental drivers of green innovation: evidence from nonlinear ARDL. Econ Res Istraz 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2026241

Kalsoom T, Ahmed S, Rafi-Ul-shan PM et al (2021) Impact of IoT on manufacturing industry 4.0: a new triangular systematic review. Sustain 13:1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212506

Kock N (2015) Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assesment Approach. Int J e-Collaboration 11:1–10

Lee JW, Kim YM, Kim YE (2018) Antecedents of adopting corporate environmental responsibility and Green Practices. J Bus Ethics 148:397–409

Li G, Li L, Choi T, Sethi SP (2020) Green supply chain management in chinese firms: innovative measures and the moderating role of quick response technology. J Oper Manag 66:958–988

Lin C-Y, Ho Y-H (2008) An empirical study on Logistics Service Providers’ intention to adopt Green Innovations. J Technol Manag Innov 3:17–26

Lin CY, Alam SS, Ho YH et al (2020) Adoption of green supply chain management among SMEs in Malaysia. Sustain 12:1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166454

Ma Y, Hou G, Yin Q et al (2018) The sources of green management innovation: does internal efficiency demand pull or external knowledge supply push? J Clean Prod 202:582–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.173

Maasoumi E, Heshmati A, Lee I (2020) Green innovations and patenting renewable energy technologies. Empir Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01986-1

Meixell MJ, Luoma P (2015) Stakeholder pressure in sustainable supply chain management: a systematic review. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 45:16–42

Mirzaei NE, Hilletofth P, Pal R (2021) Challenges to competitive manufacturing in high – cost environments: checklist and insights from swedish manufacturing firms. Oper Manag Res 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-021-00193-0

Morais DOC, Silvestre BS (2018) Advancing social sustainability in supply chain management: Lessons from multiple case studies in an emerging economy. J Clean Prod 199:222–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.097

Mungkung R, Sorakon K, Sitthikitpanya S, Gheewala SH (2021) Analysis of green product procurement and ecolabels towards sustainable consumption and production in Thailand. Sustain Prod Consum 28:11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.03.024

Paulraj A, Chen IJ, Blome C (2017) Motives and performance outcomes of sustainable supply Chain Management Practices: a multi-theoretical perspective. J Bus Ethics 145:239–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2857-0

Pinto L (2020) Green supply chain practices and company performance in portuguese manufacturing sector. Bus Strateg Environ 29:1832–1849

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 63:539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Prouteau L, Wolff F-C (2008) On the relational motive for volunteer work. J Econ Psychol 29:314–335

Qazi AA, Appolloni A, Shaikh AR (2022) Does the stakeholder ’ s relationship affect supply chain resilience and organizational performance ? Empirical evidence from the supply chain community of Pakistan. Int J Emerg Mark. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-08-2021-1218

Qin X, Ren R, Zhang Z, Johnson RE (2018) Considering self-interests and symbolism together: how instrumental and value‐expressive motives interact to influence supervisors’ justice behavior. Pers Psychol 71:225–253

Qin X, Godil DI, Sarwat S et al (2021) Green practices in food supply chains: evidence from emerging economies. Oper Manag Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-021-00187-y

Rahman HU, Zahid M, Ullah M, Al-Faryan MAS (2023) Green supply chain management and firm sustainable performance: the awareness of China Pakistan Economic Corridor. J Clean Prod 414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137502

Rehman SU, Shahzad M, Ding X, Razzaq A (2023) Impact of corporate motives for sustainable sourcing: key moderating role of regulatory pressure. Environ Sci Pollut Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27463-7

Reiss S (2012) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Teach Psychol 39:152–156

Rogetzer P, Silbermayr L, Jammernegg W (2018) Sustainable sourcing of strategic raw materials by integrating recycled materials. Flex Serv Manuf J 30:421–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10696-017-9288-4

Rousseau DM, Tijoriwala SA (1999) What’s a good reason to change? Motivated reasoning and social accounts in promoting organizational change. J Appl Psychol 84:514

Sarkis J, Zhu Q, Lai KH (2011) An organizational theoretic review of green supply chain management literature. Int J Prod Econ 130:1–15

Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Hair JFJ (2017) Partial least squares structural equation modeling. Springer International Publishing AG

Schulze H, Bals L, Warwick J (2022) A sustainable sourcing competence model for purchasing and supply management professionals. Oper Manag Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-022-00256-w

Shahzad M, Qu Y, Rehman SU et al (2019) Impact of knowledge absorptive capacity on corporate sustainability with mediating role of CSR: analysis from the asian context. J Environ Plan Manag 63:148–174

Shahzad M, Qu Y, Javed S et al (2020a) Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: a case of pakistani manufacturing industry. J Clean Prod 253:119938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119938

Shahzad M, Qu Y, Zafar AU et al (2020b) Translating stakeholders’ pressure into environmental practices - the mediating role of knowledge management. J Clean Prod 275:124163

Shahzad M, Qu Y, Zafar AU et al (2020c) Exploring the influence of knowledge management process on corporate sustainable performance through Green Innovation. J Knowl Manag 24:2079–2106

Shahzad M, Qu Y, Rehman SU et al (2022a) Impact of stakeholders’ pressure on green management practices of manufacturing organizations under the mediation of organizational motives. J Environ Plan Manag 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2022.2062567

Shahzad M, Qu Y, Rehman SU, Zafar AU (2022b) Adoption of green innovation technology to accelerate sustainable development among manufacturing industry. J Innov Knowl 7:100231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100231

Shin H, Collier DA, Wilson DD (2000) Supply management orientation and supplier/buyer performance. J Oper Manag 18:317–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(99)00031-5

Shu C, Zhou KZ, Xiao Y (2016) How Green Management Influences Product Innovation in China: the role of institutional benefits. J Bus Ethics 133:471–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2401-7

Siems E, Seuring S, Schilling L (2022) Stakeholder roles in sustainable supply chain management: a literature review. J Bus Econ 93:747–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-022-01117-5

Sun Y, Shahzad M, Razzaq A (2022) Sustainable organizational performance through blockchain technology adoption and knowledge management in China. J Innov Knowl 7:100247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100247

Thomas RW, Fugate BS, Robinson JL, Tasçioglu M (2016) The impact of environmental and social sustainability practices on sourcing behavior. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 46

Touboulic A, Walker H (2016) A relational, transformative and engaged approach to sustainable supply chain management: the potential of action research. Hum Relations 69:301–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715583364

Wetzels M, Odekerken-Schröder G, Van Oppen C (2009) Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q 33:177

Yousaf Z (2021) Go for green: green innovation through green dynamic capabilities: accessing the mediating role of green practices and green value. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:54863–54875. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14343-1

Yu Y, Choi Y (2016) Stakeholder pressure and CSR adoption: the mediating role of organizational culture for chinese companies. Soc Sci J 53:226–235

Zhou B, Siddik AB, Zheng G-W, Masukujjaman M (2023) Unveiling the role of Green Logistics Management in improving SMEs’ sustainability performance, vol 11. Do Circular Economy Practices and Supply Chain Traceability Matter? Systems

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shahzad, M., Rehman, S.U., Zafar, A.U. et al. Sustainable sourcing for a sustainable future: the role of organizational motives and stakeholder pressure. Oper Manag Res 17, 75–90 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-023-00409-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-023-00409-5