Abstract

This paper examines the antecedents of organizational commitment for adopting corporate environmental responsibility and green practices in the case of the logistics industry in South Korea. Seven hundred and eighty employees and top management from logistics companies were sampled. The data were analyzed using factor analysis, structural equation modeling techniques, and one-way analysis of variance. The results showed that social expectations, organizational support, and stakeholder pressure were the important antecedents for the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices. In the path analysis, social expectations had the greatest impact on both stakeholder pressure and green practice adoption. Moreover, we found that the higher the job titles were, the more willing they were to adopt green practices. This indicated that the current top management of Korean logistics companies is well aware of being mandated to make a commitment to corporate environmental responsibility and green practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The broader social concern of corporate social responsibility and environmental responsibility has currently become a dominant theme. Having a culture of proactive corporate social responsibility and environmental responsibility is quickly becoming a source of competitive advantage for many companies. Meanwhile, the leaders of major corporations worldwide are increasingly facing the challenge of managing organizations that should meet the expectations of a broad range of stakeholders and deliver a return in line with these expectations at the same time. As a result, practicing corporate social responsibility and environmental responsibility have become the necessary ingredients for a company’s long-term success. Eccles et al. (2012) reported that high responsibility organizations are characterized by a governance structure that explicitly takes into account the environmental and social benefits of the company, in addition to financial benefits. They also found that companies that manage their environmental and social benefits have superior financial benefits and actually create more value for their shareholders.

The logistics industry plays an important role in the Korean economy. These firms provide logistics services for their customers including warehousing, transportation, inventory management, order processing, and packaging. With the fast growth of the Korean economy, the demand for logistics services has been growing rapidly. The total economic contribution rate of the logistics industry to the gross domestic product (GDP) of Korea was 2.8 % in 2010 and the total economic cost of logistics services to GDP was 9.1 % in 2010 (National Logistics Information Center of Korea 2011). Thus, the logistics industry in Korea is perceived as one of the least productive industries and a dirty industry that provides lower value jobs in terms of their education level and wealth and also produces the most environmental pollution. To transform the logistics industry from the least productive industry to a “better” one and from a dirty industry to a clean one, the Korean government has formed a master plan to support the logistics industry by increasing the industry’s economic contribution up to 5.0 % by 2020. Meanwhile, the government aims to reduce the logistics cost of the economy down by 5.5 % by 2020 and reduce 15 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport of the Republic of Korea 2011). In the meantime, the negative environmental impact of the logistics industry has been an important issue in Korea and many logistics and transportation services usually result in several negative environmental impacts including air pollution, improper waste disposal, and excessive fuel consumption. (Jo 2010; Kim and Lee 2011; Kim and Yoo 2012). In this regard, the Korean government has stipulated several new environmental policies, and logistics companies accordingly have begun to adopt best environmental management practices.

Many logistics companies in Korea, however, represent small businesses—typically defined as firms with 50 or fewer employees—paying little attention to environmental issues thus far while limiting consuming resources for the effort and generating both greenhouse gases and industrial waste (Kim 2012; Kim and Han 2011). For these reasons, the government advocates taking a more long-term view for this process, instead of carrying out its mandated mission of strengthening regulations on the environmental pollution and vehicle emissions standards. The government has been taking positions that favor an industry’s voluntary actions, industry trade associations, and government watchdogs. It is time that the logistics industry makes more of an effort to adopt “better” environmental management practices.

Various explanations have been proposed as to what factors influence firms’ adoption of green practices. Stakeholder pressure, environmental regulation, company size, top management’s characteristics, and quality of human resources are relevant environmental and organizational variables frequently appearing in the literature (Etzion 2007; González-Benito and González-Benito 2006b; Lin and Ho 2011). Although organizational and environment regulatory factors have been taken into account in several studies on green practice issues (Gadenne et al. 2009; Williamson et al. 2006), much still remains to be examined empirically about how organizational factors and environment regulatory factors influence green practice adoption for the logistics industry. As applying new environmental standards into corporate operations requires exploring new resource combinations and deploying existing resources in new ways, green practice adoption involves implementing new or modified processes to reduce environmental pollution, which can be regarded as an innovation process (Henriques and Sadorsky 2007; Rothenberg and Zyglidopoulos 2007).

In order to fill this research gap, this paper sought to identify antecedents influencing the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices for logistics firms in Korea. This paper examined the main components of corporate social responsibility dimensions, namely social expectation, organizational behavior, and stakeholder theories, in order to determine organizations’ behavioral intentions to adopt corporate environmental responsibility and green practices. This study assumed that social expectations, organizational support, and stakeholder pressures for the environment may have an impact on the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices.

Literature Review

Social Expectations for the Environment

Social expectation theory refers to a body of social theories that are concerned with how our socially received expectations motivate our behavior. In this regard, people tend to adopt social norms and to change their behavior to meet the expectations that society provides. In this way, social expectations for the environment provide ethical norms to form moral judgments about the environment. Social expectations may play a role in how corporations perceive their environmental obligations and responsibilities. In this way, we may have a better understanding of how socially received expectations motivate business organizations’ behavioral intentions. Corporate social responsibility, which is mirrored in social expectations, indicates that corporations have an ethical responsibility to treat the public and the environment with dignity and respect.

Iyer (2006, 2009) suggested that the relationship between corporations and society is essentially dynamic and heterogeneous, thus it is difficult to characterize the relationship in terms of the social contract concept. However, the economic aspect of corporations is finely intertwined with society. Torugsa et al. (2013) found that proactive corporate social responsibility involves business practices adopted voluntarily by firms that go beyond regulatory requirements in order to support economic and environmental sustainability and thereby contribute positively to society. Mueller et al. (2009) reported that corporations implement social and environmental standards as instruments toward corporate social responsibility in supply chains and such standards increase legitimacy among stakeholders. That being said, examples of corporate environmental responsibility include carbon emission reduction policies, green supply chain policies, energy and water efficiency strategies. Arend (2014) reported that small businesses can build a competitive advantage with their environmental practices, while some tradeoffs exist between activities aimed at financial performance and at improving environmental performance. Baker (2003) reported that proactive corporate social responsibility leads to corporate environmental responsibility in utilizing both internal and external resources in bringing harmony to society. Peng and Lin (2008) reported that local community expectations for environmental responsibility have a positive effect on the level of green practice adoption of corporations.

Organizational Support for the Environment

Much of the literature discusses a variety of organizational characteristic variables—such as top management’s leadership skills, quality of human resources, organizational culture, and organization size—which influence their environmental strategy (Etzion 2007; González-Benito and González-Benito 2006b). Among others, sufficient organizational resources and qualified organizational learning capabilities are two relevant organizational characteristics advancing innovation (Jeyaraj et al. 2006), environmental benefits (Kim 2012; Lin and Ho 2010), and green practice adoption (Álvarez-Gil et al. 2007; Lee 2008; Lin and Ho 2011; Zhu et al. 2008).

Organizational support refers to the extent to which a company supports its employees to use a particular technology or system that influences innovation. Stawiski et al. (2010) found that corporate social responsibility is beneficial because it improves employees’ perceptions of the company. When a company has conducted corporate social responsibility initiatives, employees are more proud and committed to the organization (Brammer et al. 2007). Stawiski et al. (2010) also found that employees’ perceptions of their organizations’ concern for society and the environment were linked to their level of organizational commitment. That is, the higher an employee rates his/her organization’s corporate citizenship, the more committed he/she is to the organization. In this regard, the top management plays an important role; the central task of top management is to acquire resources and allocate them efficiently so that the company is able to adopt green practices to achieve an environmental competitive advantage (González-Benito and González-Benito 2006a). Ensuring the availability of financial and technical resources for innovation has positive effects on the adoption of innovation (Lee et al. 2005).

Adopting green practices is, to some extent, a complicated process requiring cross disciplinary coordination and significant changes in the existing operation process (Russo and Fouts 1997). Adoption requires intensive efforts in human resources and depends on the development and training of tacit skills through the employees’ involvement (del Brío and Junquera 2003). Employees with competent learning capabilities will be easily involved in training programs that can improve companies’ innovative capacities and further advance green practice adoption. The degree to which an organization is receptive to new ideas will influence its propensity to adopt new technologies (Frambach and Schillewaert 2002). A company with higher innovative capacity will be more likely to successfully implement an advanced environmental strategy (Christmann 2000). For the adoption of environmental responsibility and green practices, therefore, organizational support is essential because the resources required for adopting green practices will be more easily available; thus, the employees will be motivated to implement green behaviors.

Stakeholder Pressure for the Environment

Several stakeholders such as society, local community, employees, management, and shareholders among others have been discussed in the previous sections. Stakeholders are individuals or groups who can affect a company’s activities. They play an important role in organizational decision-making processes and are widely involved in various environmental issues. Stakeholder pressure is regarded as the most prominent factor influencing a company’s environmental strategy (Buysse and Verbeke 2003). Wolf (2014) found that stakeholder pressure and sustainable supply chain management contribute to an organization’s sustainability performance. Konrad et al. (2006) found that the relationship between corporations and stakeholders promotes sustainable development. Hummels and Timmer (2004) discussed the stakeholders’ need for social, ethical, and environmental information and the efforts of corporations to address this need.

Stakeholders such as customers, suppliers, government regulatory bodies, and non-governmental organizations have been discussed in the literature of environmental management (González-Benito and González-Benito 2006a, b; Lai and Wong 2012). Chen et al. (2014) reported that market orientation positively affects corporate environmental strategy which has a positive influence on environmental performance. In line with other advanced nations in social responsibility and environmental ethics, Korean consumers have a moderate yet increasing demand for products that are ethically sourced, manufactured, and delivered across the supply chain. The results of the 2012 Greendex survey showed that Korean consumers are, in fact, conscious of the environmental impact of their lifestyles. South Korean consumers currently rank 2nd out of 17 on the Greendex Goods sub-index (National Geographic 2012), which means that they are most likely purchasing environmentally friendly products. The expectations for green products of Korean consumers can represent a powerful driver for promoting green processes of Korean logistics and supply chain operations.

Walker et al. (2014) found that regulatory stakeholder pressure is positively related to types of environmental proactivity. Lin and Ho (2011) found that regulatory pressure has a significantly positive influence on the adoption of green practices for Chinese logistics companies. Plenty of research has revealed the positive relationship between firms’ environmental activities and government regulatory pressure (e.g., Christmann 2004; Lee 2008). Guay et al. (2004) found non-governmental organizations also influence corporate environmental conduct and so the overall influence of non-governmental organizations is growing with intended consequences for corporate environmental strategy, governance, and performance.

Ruhnka and Boerstler (1998) reported that traditional legal and regulatory pressure for corporate behavior are overwhelmingly punitive in their intended effects, while more recent governmental incentives to encourage voluntary corporate self-regulation are much more positive in their intended effects. Several researchers have suggested that governmental incentives are more relevant factors influencing technical innovation than regulatory pressure (Lee 2008; Lin and Ho 2011; Scupola 2003). Rodríguez et al. (2013) found governmental incentives are associated with pollution prevention. Shu et al. (2014) found that governmental support more strongly mediates the effect of green management on radical product innovation than its effect on incremental product innovation. The availability of external resources will influence the adoption of green practices (Aragon-Correa and Sharma 2003; Rothenberg and Zyglidopoulos 2007). Governments can advance technical innovation by encouraging such policies by providing financial incentives and technical resources. The government can increase its support by providing tax incentives for alternative energy and environmentally friendly technologies, and lower insurance premiums for lower environmental risks (Lee 2008; Lin and Ho 2011).

Adoption of Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Green Practices

Peters and Romi (2014) suggested that voluntary environmental governance mechanisms operate to enhance a firm’s environmental legitimacy, whereas corporate governance mechanisms have a role in responding to stakeholders’ concerns about environmental risks. Lion et al. (2013) reported that environmental impact assessments have emerged as a key tool for businesses to manage the negative impact of their activities on the environment. Giménez and Sierra (2013) found that environmental governance mechanisms and supplier assessment have a positive and synergistic effect on environmental performance. Lannelongue et al. (2014) reported that, while environmental motivations based on the search for legitimation lead to more incomplete styles of environmental management, competitive motivations entail a more complete environmental management, showing more effective environmental performance of organizations.

Done correctly, companies have enormous potential to effect change in their communities and the environment by investing in corporate social and environmental initiatives. Potential organizational benefits of adopting corporate environmental responsibility and green practices include reduced energy and natural resource consumption, reduced waste and pollutant emissions, improved financial benefits, increased company market value, increased corporate image, and greater responsiveness to social expectations for the environment (del Río González 2005; Goldsby and Stank 2000; Murphy et al. 2006; Zhu et al. 2007). The benefits will serve as motivation for business organizations to adopt their environmental responsibility and green practices.

Hypotheses and Research Framework

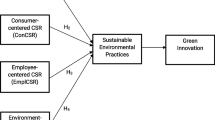

Based on the evidence and findings from the previous literature, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

Social expectations for the environment are likely to have a positive effect on organizational support for the environment.

Hypothesis 2

Social expectations for the environment are likely to have a positive effect on stakeholder pressure for the environment.

Hypothesis 3

Organizational support is likely to have a positive effect on the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices.

Hypothesis 4

Stakeholder pressure is likely to have a positive effect on the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices.

Hypothesis 5

Social expectations are likely to have a positive effect on the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices.

Figure 1 displays a conceptual model and research framework of adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices.

Research Methods

Survey and Sample Characteristics

According to the statistics (The Korea Federation of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises 2012), a total of 340,526 companies with 1,043,861 employees in the logistics industry—including road transportation services, warehouse services, storage, and packing services—registered with the government as of December 2009: 8779 small- and medium-sized enterprises (defined as firms with 50 or fewer employees in Korea) with 450,572 employees registered, 208 large enterprises (defined as firms with 100 or more employees in Korea) with 226,932 employees registered, and 331,539 micro enterprises (defined as firms with three or fewer employees in Korea) with 366,357 employees registered with the government. 95 % of companies of the logistics and transportation industry in South Korea are micro and small enterprises. The total number of 8779 small- and medium-sized enterprises with 450,572 employees is singled out as being fundamental in the growth and development of this sector.

Of the 8779 small- and medium-sized enterprises, a mail survey was conducted with the National Logistics Information Center of Korea. 1500 sets of questionnaires were mailed to 500 small- and medium-sized companies listed on the logistics company directory of the National Logistics Information Center of Korea. Of 824 filled out and returned questionnaires in the mail survey, 44 cases were removed from the dataset because they contained missing data or outliers. The final sample size included 780 cases that had no missing data and was used for the analyses. We admit that there is a possible selection bias of 500 companies out of 8779 companies and using mail surveys for data collection is still questionable as to whether the survey method is able to generate data that does represent the entire population. It is said that all kinds of sampling methods for data collection for this type of empirical research inherently have some biases concerning representativeness (Szolnoki and Hoffmann 2013). Table 1 provides the sample statistics.

Given that the model embeds complex relationships in the path of adopting corporate environmental responsibility and green practices, this study collected self-reported corporate employees’ perceptions using a questionnaire. An initial structured questionnaire was developed based on a study of the existing literature (e.g., Kacmar et al. 1999; Kim and Lee 2011; Lin and Ho 2011; Rao and Holt 2005; Zhu et al. 2007) and the model’s hypotheses with 13 participants in focus group interviews. The initial questionnaire included 23 items related to various constructs discussed in this study and 5 items that captured information pertaining to respondents’ gender, age, company location, job position titles, and work experience in the logistics industry. The questionnaire was refined based on the feedback and the initial analysis. A final questionnaire retained 18 items related to the various constructs and 5 items for demographic information.

The principles of scale design and development are well documented (e.g., Nunnally and Bernstein 1994), and they describe methods of item selection, content validation, construct validation reliability assessment, scaling, and analysis. The sensitivity of data in measuring individuals’ perceptions and behavioral intentions in many different cultural contexts poses a problem for the adoption of a single superior scale due to limited data comparability (Bartoshuk et al. 2005; Dawes 2008). For this reason, different researchers have employed different scales in their measurements of consumer perceptions and behaviors as one size does not fit all. Therefore, a 5-point Likert type scale was used in this study to be consistent with research in a different cultural context and the response options in this research ranged from (1) strongly disagree, and (3) neutral, to (5) strongly agree, as noted in Appendix Table 5.

Factor Analysis and Internal Consistency Reliability Test

Evidence of the effectiveness of our scale was examined. Bartholomew (1996) and Basilevsky (1994) provided a comprehensive description of scale development and validation. Many methods of validation rely heavily on the analysis of inter-item or inter-scale correlations. Construct validity embraces a variety of techniques for assessing the degree to which an instrument measures the concept that it is designed to measure. This may include testing dimensionality and homogeneity. Construct validation is best seen as a process of learning more about the joint behavior of the items and of making and testing new predictions about this behavior. Factor analysis is an often-used key technique in this process. In order to ensure the construct validity of the measurement instrument, factor analysis was employed in a two-stage process. First, exploratory factor analysis with a varimax rotation procedure was employed to identify underlying predictors based on an eigenvalue cut-off of one. Second, confirmation factor analysis using structural equation modeling techniques was employed to confirm that the identified predictors comprised the items correctly and reliably.

To identify underlying antecedents of green practice adoption, factor analysis with a varimax rotation procedure was employed. The component factor analysis was used to uncover the underlying structure of a large set of items and identified four components: component one with four items “social expectations” (eigenvalue = 2.731), component two with three items “organizational support” (eigenvalue = 2.014), component three with four items “stakeholder pressure” (eigenvalue = 2.568), and component four with four items “green practice adoption” (eigenvalue = 2.348). This resulted in the retention of 15 items out of 18, which represented the four components. Afterward, the four components were used for the following analyses.

To test the appropriateness of factor analysis, two measures, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin and the Bartlett’s test, were used. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin overall measure of sampling adequacy of 0.802 fell within the acceptable significance level at p < 0.01. Bartlett’s test of sphericity of 4698.077 with 105° of freedom showed a highly significant correlation among the survey items at p < 0.01. The sum of square loadings from the four components explained 64.412 % of the total variance of the data. The results of exploratory factor analysis using principal component analysis extraction methods are reported in Table 2.

Internal consistency reliability is a measure of how well a test addresses different constructs and delivers reliable scores. A more comprehensive description of scale development and reliability is provided by Dunn (1989). Three main reliability tests are split halves, Kuder Richardson, and Cronbach’s alpha tests. These tests check that the results and constructs measured by a test are correct, and the subject, size, and response of the data set dictate the exact type used. However, the most common method for assessing internal consistency is Cronbach’s alpha. This form of intra-class correlation is closely related to convergent validity, i.e., the extent to which the items in a scale are all highly inter-correlated. For example, in a series of questions that ask the subjects to rate their response between one and seven, Cronbach’s alpha gives a score between zero and one, with 0.7 and above being reliable. The test also takes into account both the size of the sample and the number of potential responses.

The Cronbach’s alpha test is preferred in this study due to the benefit of averaging the correlation between every possible combination of split halves and allowing multi-level responses. For example, the survey items were divided into the four constructs. The internal consistency reliability test provides a measure so that each of these particular constructs is measured correctly and reliably. The results of internal consistency reliability tests for the four constructs of green practice adoption were reported as follows: “social expectations” (4 items, α = 0.795), “organizational support” (3 items, α = 0.719), “stakeholder pressure” (4 items, α = 0.815), and “green practice adoption” (4 items, α = 0.769). The detailed results of internal consistency reliability tests, including item-total correlation coefficient values, are reported in Table 2.

The confirmatory factor analysis using structural equation modeling techniques was employed to confirm that the identified antecedents fit the items correctly and reliably. The results of confirmation factor analysis indicated that single factor solutions fit the items acceptably. The corrected item-total correlation value of each item to the construct is presented in Table 2.

Results

Structural Equation Model Estimates and Path Diagram

The analysis of moment structures was used for an empirical test of the structural model. The maximum-likelihood estimation was applied to estimate numerical values for the components in the model. In the process of identifying the best-fit model, multiple models were analyzed because we were testing competing theoretical models. From a predictive perspective, we determined which model fit the data best, but sometimes the differences between the models appeared small on the basis of the fit indexes. When comparing non-nested models, the Akaike information criterion fit index was used as our first choice because the difference in the Chi square values among the models cannot be interpreted as a test statistic (Kline 2005), the root mean square of approximation fit index as our second choice, and then the goodness-of-fit index as our third choice.

The results of the analysis of moment structures generally achieved acceptable goodness-of-fit measures. For example, the index of the goodness-of-fit index (=0.927) indicated that the fit of the proposed model was about 93 % of the saturated model (the perfectly fitting model). The index of the normed fit index (=0.914) indicated that the fit of the proposed model was about 91 %. The other goodness-of-fit measures were as follows:

Model fit measures The minimum value of the sample discrepancy (=894.434), degrees of freedom (=84), the goodness-of-fit index (=0.927), the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (=0.913), the parsimony goodness-of-fit index (=0.905), the root mean square residual (=0.044), and the root mean square of approximation (=0.038).

Baseline comparisons measures The Bentler–Bonett normed fit index (=0.914), the Bollen’s relative fit index (=0.902), the Tucker–Lewis coefficient index (=0.938), and the comparative fit index (=0.946).

Parsimony-adjusted measures The parsimony ratio (=0.905), the parsimony normed fit index (=0.872), the parsimony comparative fit index (=0.895), the estimate of the non-centrality parameter (=810.434), the Akaike information criterion (=966.434), the Browne–Cudeck criterion (=967.943), and the Bayes information criterion (=1134.168). Table 3 displays the estimates of green practice adoption using the structural equation model.

In testing Hypotheses 1 and 2, social expectations for the environment had a positive effect on both organizational support and stakeholder pressure for the environment. The results in Table 3 showed a significant positive relationship at a 95 % CI (p < 0.01). Social expectations for the environment had a positive propensity toward strong organizational support and increased stakeholder pressure for the environment. In the meantime, social expectations for the environment had a positive and direct effect on the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices (p < 0.01).

Hypotheses 3 and 4 tested the relationships between organizational support and green practice adoption and between stakeholder pressure and green practice adoption (ps < 0.01). Both organizational support and stakeholder pressure positively and directly influenced the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices.

In testing Hypothesis 5 that social expectations for the environment had a positive effect on the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices, the result in Table 3 showed a significant positive relationship at a 95 % CI (p < 0.01). Social expectations had a positive propensity toward green practice adoption of corporations. In the meantime, social expectations for the environment had a positive and direct effect on both organizational support and stakeholder pressure.

Overall, the three components of social expectations, organizational support, and stakeholder pressure for the environment served as important antecedents for the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices. In the path, social expectations had the greatest impact on both stakeholder pressure and green practice adoption. In Table 3, the 0.557 total effect of social expectations on the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices consisted of a direct effect of 0.352 and an indirect effect of 0.205 via organizational support and stakeholder pressure. Figure 2 displays the structural equation model and path diagram of green practice adoption.

The structural equation model and path diagram of green practice adoption. Note Fig. 2 shows the measurement components and the structural components by using thin lines. Big circles represent the latent variables that are unobserved endogenous variables, while rectangles represent the measure variables that are observed endogenous variables. The numeric values on the lines represent the coefficient values of the parameters estimated in the model. Coefficient is statistically significant at 95 % CI (*** p < 0.01)

Demographic Differences in Green Practice Adoption

One-way analysis of variance was conducted to compare means of the four constructs by job titles and positions of the respondents. Table 4 shows statistically significant mean differences in social expectations, organizational support, stakeholder pressure, and green practice adoption, respectively (p < 0.01). The results in Table 4 showed that the respondents with higher positions and titles had a more positive perception of their commitment to green practice adoption. The results meant that the current top management of the Korean logistics industry was well aware that they have been mandated to make a commitment to the environment, environmental sustainability, greenhouse gas emissions reduction, efficient use of energy and resources, and corporate environmental responsibility and green practices.

Discussion and Policy Implications

The results of this study showed that perceived social expectations exerted the most important influence on firms’ behavior to adopt corporate environmental responsibility and green practices. The positive impact of organizational support and stakeholder pressure on the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices was also of special interest. The results indicated that perceived social expectations, organizational support (availability of internal resources), and stakeholder pressure (availability of external resources) were viewed as important antecedents for the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices.

The results of Hypotheses 1, 2, and 5 highlighted the role of perceived social expectations of corporate employees and top management in promoting the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices of logistics companies in Korea. The perceived social expectations of corporate employees and top management were one of the most critical antecedents in promoting the positive perceptions of organizational support and stakeholder pressure and resulted in the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices. Accordingly, the increasing organizational support and stakeholder pressure in the process drove the green practice adoption of Korean logistics companies. Greenhouse gas emissions, fuel efficiency in transportation, and efficient energy use in warehouse management are probably the most critical environmental issues of the logistics and transportation industry in Korea, which have become the key environmental issues of organizational support and stakeholder pressure in the Korean logistics industry. By becoming aware of the ever increasing expectations from society and local communities for corporate environmental responsibility and environmental ethics companies in this sector should make a substantial contribution to reducing their greenhouse gas emissions and other environmental impacts as well as improve the operational efficiency and economic profitability of their businesses.

The result of Hypothesis 3 highlighted the role of perceived organizational support in facilitating the green practice adoption of logistics companies in Korea. The perceived organizational support (availability of organizational resources) of corporate employees and top management was a critical antecedent of the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices. Strong organizational support and the quality of human resources facilitated the green practice adoption of Korean logistics companies. The acknowledgement of strong organizational support and the availability of internal resources provided employees with motivation and resources required to make environmental commitments and adopt green practices.

The result of Hypothesis 4 highlighted the role of perceived stakeholder pressure in driving the green practice adoption of logistics companies in Korea. The perceived stakeholder pressure (availability of external resources) of corporate employees and top management was also a critical antecedent of the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices. Both non-governmental organizations’ pressure and governmental regulatory pressure drove the fast adoption of green practices of Korean logistics companies. In this regard, government actions will force a green agenda on the industry in a top-down approach. Although this may be the least desirable outcome for the logistics industry, it is already evident that government intervention and legislation are directly impacting environmental issues of the logistics industry. For example, legislation controlling the movement of hazardous goods, reducing packaging waste, stipulating the recycled content of products, and the mandatory collection and recycling of products is already evident in the economy. Although there are clear trends in policy guidelines that make users pay the full costs of using the resources, many logistics and transportation companies in Korea have largely escaped these initiatives.

The results in Table 4 showed that the respondents with higher positions and titles had a more positive perception of their commitment to green practice adoption. The current top management of the Korean logistics industry was well aware that they have been mandated to make a commitment to environmental responsibility and green practices. Based on the findings from this study, governmental regulatory bodies should be aware of the reality that most logistics and transportation companies in Korea are still small enterprises and thus they may suffer from a lack of financial, technical, and qualified human resources. Although most logistics and transportation companies in Korea, regardless of their size and business scope, are well aware of the importance of their environmental commitments, they are less likely to put resources into adopting new technologies and green practices as they have a tendency to focus on the short-term return on their investments. In addition, small companies in such less productive industries will put more resources into improving their primary business activities but allocate fewer resources to environmental responsibility and green practices. Therefore, policy makers may offer economic incentives and provide required resources to the logistics industry for achieving their environmental commitments. Policy makers should put more efforts in encouraging logistics companies to adopt green practices, instead of enforcing new environmental rules and standards.

In summary, logistics and transportation companies in Korea are consequently under heavy pressure from both outside and inside factors to be more proactive and accountable for a wide range of environmental responsibilities and adopting green practices. The ever increasing social expectations for corporate environmental responsibility and green practices require logistics companies to publicly report on their assessments of making environmental commitments and adopting green practices. Such regulatory pressure and increasing social expectations for the environment, whether rational or not, should be seen in the context of the business sector’s reality. Therefore, the role of the logistics and transportation industry in the economy will be changing and will become an active partner in promoting corporate environmental responsibility and green practices. As a result, green practices in the Korean logistics industry are more likely to be adopted if, in addition to regulatory pressure, the government provides a wide range of incentives available for implementing measures in compliance with the new environmental rules and standards that have complicated business operations in the logistics industry even further.

Conclusions

This paper examined antecedents for the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices of the Korean logistics industry. The results showed that perceived social expectations, organizational support, and stakeholder pressure were important antecedents for the adoption of corporate environmental responsibility and green practices. In the path analysis, social expectations had the highest impact on both stakeholder pressure and green practice adoption. Moreover, we found that the higher the job titles were, the more willing they were to adopt green practices.

Future research is needed to generalize these findings and could examine other business sectors (for example, clean industries versus dirty industries, high-tech industries versus low-tech (labor-intensive) industries) from different levels of economic development (for example, developed economies versus developing economies) as potential sources of variation in the antecedents of organizational commitment to adopt corporate environmental responsibility and green practices.

References

Álvarez-Gil, M. J., Berrone, P., Husillos, F. J., & Lado, N. (2007). Reverse logistics, stakeholders’ influence, organizational slack, and managers’ posture. Journal of Business Research, 60(5), 463–473.

Aragon-Correa, J. A., & Sharma, S. (2003). A contingent resource-based view of proactive corporate environmental strategy. Academy of Management Review, 28(1), 71–88.

Arend, R. J. (2014). Social and environmental performance at SMEs: Considering motivations, capabilities, and instrumentalism. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 541–561.

Baker, M. (2003). Corporate social responsibility in 2003: A review of the year. Business Respect, 68. Retrieved Feb 25, 2014 from http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/APCITY/UNPAN016538.pdf

Bartholomew, D. J. (1996). The statistical approach to social measurement. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Bartoshuk, L. M., Fast, K., & Snyder, D. J. (2005). Differences in our sensory worlds: Invalid comparisons with labeled scales. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(3), 122–125.

Basilevsky, A. (1994). Statistical factor analysis and related methods. New York, NY: Wiley.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18, 1701–1719.

Buysse, K., & Verbeke, A. (2003). Proactive environmental strategies: A stakeholder management perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 24(5), 453–470.

Chen, Y., Tang, G., Jin, J., Li, J., & Paillé, P. (2014). Linking market orientation and environmental performance: The influence of environmental strategy, employee’s environmental involvement, and environmental product quality. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2059-1.

Christmann, P. (2000). Effects of ‘‘best practices’’ of environmental management on cost advantage: The role of complementary assets. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 663–680.

Christmann, P. (2004). Multinational companies and the natural environment: Determinants of global environmental policy standardization. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5), 747–760.

Dawes, J. (2008). Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An experiment using 5-point, 7-point and 10-point scales. International Journal of Market Research, 50(1), 61–77.

Del Brío, J. A., & Junquera, B. (2003). A review of the literature on environmental innovation management in SMEs: Implications for public policies. Technovation, 23(12), 939–948.

Del Río González, P. (2005). Analysing the factors influencing clean technology adoption: A study of the Spanish pulp and paper industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 14(1), 20–37.

Dunn, G. (1989). Design and analysis of reliability studies. London: Arnold.

Eccles, R., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2012). Is responsibility now the key to corporate success? Guardian Professional Network. Retrieved Feb 25, 2013 from the Guardian website http://www.guardian.co.uk/sustainable-business/responsibility-key-corporate-success.

Etzion, D. (2007). Research on organizations and the natural environment, 1992–present: A review. Journal of Management, 33(4), 637–664.

Frambach, R. T., & Schillewaert, N. (2002). Organizational innovation adoption: A multi-level framework of determinants and opportunities for future research. Journal of Business Research, 55(2), 163–176.

Gadenne, D. L., Kennedy, J., & McKeiver, C. (2009). An empirical study of environmental awareness and practices in SMEs. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(1), 45–63.

Giménez, C., & Sierra, V. (2013). Sustainable supply chains: Governance mechanisms to greening suppliers. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(1), 189–203.

Goldsby, T. J., & Stank, T. P. (2000). World-class logistics benefits and environmentally responsible logistics practices. Journal of Business Logistics, 21(2), 187–209.

González-Benito, J., & González-Benito, O. (2006a). A review of determinant factors of environmental proactivity. Business Strategy and the Environment, 15(2), 87–102.

González-Benito, J., & González-Benito, O. (2006b). The role of stakeholder pressure and managerial values in the implementation of environmental logistics practices. International Journal of Production Research, 44(7), 1353–1373.

Guay, T., Doh, J. P., & Sinclair, G. (2004). Non-governmental organizations, shareholder activism, and socially responsible investments: Ethical, strategic, and governance implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(1), 125–139.

Henriques, I., & Sadorsky, P. (2007). Environmental, technical and administrative innovations in the Canadian manufacturing industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 16(2), 119–132.

Hummels, H., & Timmer, D. (2004). Investors in need of social, ethical, and environmental information. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(1), 73–84.

Iyer, A. A. (2006). The missing dynamic: Corporations, individuals and contracts. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(4), 393–406.

Iyer, A. A. (2009). Corporate social responsibility and farmer suicides: A case for Benign paternalism? Journal of Business Ethics, 85(4), 429–443.

Jeyaraj, A., Rottman, J. W., & Lacity, M. C. (2006). A review of the predictors, linkages, and biases in IT innovation adoption research. Journal of Information Technology, 21(1), 1–23.

Jo, S.-W. (2010). Driving factors of green physical distribution and its subsequent impact on environmental and economic benefits. Journal of the Korean Industrial Economic Association, 23(2), 675–696.

Kacmar, K. M., Carlson, D. S., & Brymer, R. A. (1999). Antecedents and consequences of organizational commitment: A comparison of two scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 59, 976–994.

Kim, J.-H. (2012). Studies on green logistics in the transport system. Korea Research Academy of Distribution and Management Review, 15(5), 17–27.

Kim, S.-T., & Han, C.-W. (2011). Measuring environmental logistics practices. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics, 27(2), 237–258.

Kim, Y.-M., & Lee, K.-N. (2011). A study on the driving factors of green physical distribution and its subsequent impact on environmental and economic benefits. Journal of the Korean Academy of International Commerce, 26(3), 91–109.

Kim, T.-H., & Yoo, S.-G. (2012). A study on the green growth and government support on green physical distribution. Journal of the Korea Association for International Commerce and Information, 14(1), 315–344.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Konrad, A., Steurer, R., Langer, M. E., & Martinuzzi, A. (2006). Empirical findings on business–society relations in Europe. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(1), 89–105.

Korea Federation of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises. (2012). Industry Activity Survey 2009: Logistics and Transportation Survey. Retrieved Oct 13, 2015 from the Korea Federation of SMEs website http://220.71.4.128:8000/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=340&tblId=DT_A30005

Lai, K. H., & Wong, C. W. Y. (2012). Green logistics management and benefits: Some empirical evidence from Chinese manufacturing exporters. Omega, 40(3), 267–282.

Lannelongue, G., González-Benito, O., & González-Benito, J. (2014). Environmental motivations: The pathway to complete environmental management. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(1), 135–147.

Lee, S. (2008). Drivers for the participation of small and medium-sized suppliers in green supply chain initiatives. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 13(3), 185–198.

Lee, H.-Y., Lee, Y.-K., & Kwon, D. (2005). The intention to use computerized reservation systems: The moderating effects of organizational support and supplier incentive. Journal of Business Research, 58(11), 1552–1561.

Lin, C.-Y., & Ho, Y.-H. (2010). An empirical study on logistics services providers’ intention to adopt green innovations. Journal Technology Management & Innovation, 3(1), 17–26.

Lin, C.-Y., & Ho, Y.-H. (2011). Determinants of green practice adoption for logistics companies in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(1), 67–83.

Lion, H., Donovan, J. D., & Bedggood, R. E. (2013). Environmental impact assessments from a business perspective: Extending knowledge and guiding business practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(4), 789–805.

Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport of the Republic of Korea. (2011). National Logistics Development Plan 2011-2020. Seoul. Retrieved Feb 25, 2014 from http://www.molit.go.kr/USR/policyData/m_34681/lst.jsp

Mueller, M., dos Santos, V. E., & Seuring, S. (2009). The contribution of environmental and social standards towards ensuring legitimacy in supply chain governance. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(4), 509–523.

Murphy, P. R., Poist, R. F., & Braunschweig, C. D. (2006). Green logistics: Comparative views of environmental progressives, moderates, and conservatives. Journal of Business Logistics, 17(1), 191–211.

National Geographic (2012). Greendex 2012: Consumer choice and the environment—A worldwide tracking survey. National Geographic/GlobeScan. Toronto, Canada: GlobeScan Incorporated. Retrieved Feb 25, 2014 from http://images.nationalgeographic.com/wpf/media-content/file/NGS_2012_Final_Global_report_Jul20-cb1343059672.pdf

National Logistics Information Center of Korea (2011). Logistics Statistics. Retrieved Feb 25, 2013 from the National Logistics Information Center website http://www.nlic.go.kr/nlic/front.action

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, L. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Peng, Y.-S., & Lin, S.-S. (2008). Local responsiveness pressure, subsidiary resources, green management adoption and subsidiary’s performance: Evidence from Taiwanese manufactures. Journal of Business Ethics, 79(1–2), 199–212.

Peters, G. F., & Romi, A. M. (2014). Does the voluntary adoption of corporate governance mechanisms improve environmental risk disclosures? Evidence from greenhouse gas emission accounting. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 637–666.

Rao, P., & Holt, D. (2005). Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic benefits? International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 25(9), 898–916.

Rodríguez, M., Magnan, M., & Cho, C.-H. (2013). Is environmental governance substantive or symbolic? An empirical investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(1), 107–129.

Rothenberg, S., & Zyglidopoulos, S. C. (2007). Determinants of environmental innovation adoption in the printing industry: The importance of task environment. Business Strategy and the Environment, 16(1), 39–49.

Ruhnka, J. S., & Boerstler, H. (1998). Governmental incentives for corporate self-regulation. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(3), 309–326.

Russo, M. V., & Fouts, P. A. (1997). A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental benefits and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 534–559.

Scupola, A. (2003). The adoption of Internet commerce by SMEs in the south of Italy: An environmental, technological and organizational perspective. Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 6(1), 52–71.

Shu, C., Zhou, K.-Z., Xiao, Y., & Gao, S. (2014). How green management influences product innovation in China: The role of institutional benefits. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2401-7.

Stawiski, S., Deal, J. J., & Gentry, W. (2010). Employee perceptions of corporate social responsibility: The implications for your organization. Quick View Leadership Series, (June). Greensboro, NC: The Center for Creative Leadership.

Szolnoki, G., & Hoffmann, D. (2013). Online, face-to-face and telephone surveys: Comparing different sampling methods in wine consumer research. Wine Economics and Policy, 2(2), 57–66.

Torugsa, N. A., O’Donohue, W., & Hecker, R. (2013). Proactive CSR: An empirical analysis of the role of its economic, social and environmental dimensions on the association between capabilities and performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(2), 383–402.

Walker, K., Ni, N., & Huo, W. (2014). Is the red dragon green? An examination of the antecedents and consequences of environmental proactivity in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(1), 27–43.

Williamson, D., Lynch-Wood, G., & Ramsay, J. (2006). Drivers of environmental behaviour in manufacturing SMEs and the implications for CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(3), 317–330.

Wolf, J. (2014). The relationship between sustainable supply chain management, stakeholder pressure and corporate sustainability performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 119(3), 317–328.

Zhu, Q., Sarkis, J., Cordeiro, J. J., & Lai, K. H. (2008). Firm-level correlates of emergent green supply chain management practices in the Chinese context. Omega, 36(4), 577–591.

Zhu, Q., Sarkis, J., & Lai, K. H. (2007). Green supply chain management: Pressures, practices and benefits within the Chinese automobile industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 15, 1041–1052.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J.W., Kim, Y.M. & Kim, Y.E. Antecedents of Adopting Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Green Practices. J Bus Ethics 148, 397–409 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3024-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3024-y