Abstract

Background

The population are getting older and obesity is growing. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is increasingly used worldwide but is still used with skepticism in the elderly. The purpose of our analysis is to judge the security of LSG in patients older than 60 years compared to patients younger than 60 years.

Methods

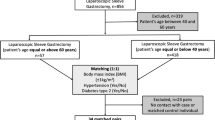

This retrospective review included data of all patients in Germany who underwent LSG between January 2005 and December 2016.The data were published online in the German Bariatric Surgery Registry. A total of 21,571 operations were gathered and divided into two groups: group I, patients < 60 years old; and group II, patients ≥ 60 years old.

Results

The total number of patients and the mean body mass index of group I and group II was 19,786, 51.7 ± 9.5 kg/m2 and 1771, 49.2 ± 8.1 kg/m2, respectively. Regarding comorbidities, group II suffered statistically significantly more comorbidities than group I (p < 0.001). The general postoperative complications were 4.9% in group I and 7.8% in group II (p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in special postoperative complications (p = 0.048) and a slightly higher intraoperative complication rate in group II (2.2% vs. 1.6%, p = 0.048). Thirty-day mortality rate for group I versus II was 0.22% and 0.23% (p = 0.977), respectively.

Conclusions

LSG is a low-risk operation and safe surgical method with acceptable, not elevated perioperative morbidity and mortality rates in patients ≥ 60 years of age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Germany, approximately 50% of women and 65% of men have a body mass index (BMI) of > 25 kg/m2. This number has increased especially among children and adolescents. In the meantime, 15% of this group are affected by overweight or obesity [1].

Especially in Germany, the rate has risen continuously over several decades, mostly in men. At present, 22.3% of men and 23.9% of women are considered obese [2].

Obesity is also an increasing problem in elderly people. Above all, the accompanying comorbidities present a high health risk. However, obesity surgery is still being treated with skepticism in patients over 60 years of age because of fear of complications and insufficient weight reduction [3].

The 12th population pre-calculation 2010 of the Federal Statistical Office states that the life expectancy in Germany, from the age of 65 years, is 24.7 years for men and 27.4 years for women [4].

Metabolic surgery is the only proven method for weight reduction. However, many surgeons are afraid to offer appropriate surgical procedures in elderly patients (≥ 60 years) as they are considered high-risk patients. In addition, the fear of possible complications exists [5].

Several studies have shown a prolonged hospitalization in open-surgical operations by patients ≥ 60 years as well as greater complication and mortality rates compared to younger age groups. Other studies demonstrated the feasibility of laparoscopic obesity surgery in elderly patients. Most of these studies focused on the laparoscopic gastric bypass and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. In addition, studies on the relatively newly established SG method are still a rarity [6].

The aim of this analysis is to elicit the safety of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) in patients over 60 years.

Materials and Methods

Data from patients who have undergone bariatric surgery in Germany have been recorded prospectively since January 1, 2005 within the framework of the German Bariatric Surgery Registry (GBSR). The basis was the Helsinki Declaration of Principles for biomedical research.

Until 2015, about 91% of all bariatric procedures performed in Germany are documented in the GBSR.

At the multicenter trial, a total of 178 hospitals actively participated during the period from 2005 to December 31, 2016. LSG was carried out by 108 institutions. For the German Society of General and Visceral Surgery certified hospitals, participation in the study was obligatory and optional for all other facilities. The analysis and retrospective evaluation of data from the prospective cohort study was performed by StatConsult GmbH and the Institute for Quality Assurance in Operative Medicine at Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg.

All patients were included in the perioperative outcomes analysis, which had a primary LSG within the period 2005 to 2016 and a valid age of at least 11 years. Since the analyses were ultimately only for patients who had primary intervention by sleeve gastrectomy, all other surgical procedures were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed with the software SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and—in an exploratory sense—intentionally calculated to a full significance level of 5%, i.e., they were not corrected with respect to multiple tests, and each p value ≤ 0.05 represents a significant result.

Outcome variables (intraoperative, general, as well as specific postoperative complications) and comorbidities defined as total rates were derived as the union of all corresponding single items. For example, intraoperative complications were given when at least one intraoperative complication was selected. Furthermore, the 30-day mortality rate was obtained from the baseline as well as from the existing follow-up data.

Unadjusted analyses were exploratorily carried out to compare age groups (< 60 years/≥ 60 years). Chi-square tests and robust t tests were performed for categorical and continuous data, respectively. For continuous variables, sample size (N), mean, and standard deviation (SD) are given. In case of high deviation from normal distribution, data were transformed using the square root. Here, mean and the simple range of dispersion (after retransformation) are presented. In detailed tables, also minima, maxima, and quantiles (Q1, median, and Q3) are provided. For categorical variables, the absolute (N) and the relative (%) frequencies are shown.

This paper evaluated the data collected between 2005 and 2016, which included the results of patients of two age groups (< 60 years/≥ 60 years) after sleeve gastrectomy, with a focus on mortality and morbidity.

The following aspects were considered for analysis:

Demographic/clinical parameters

(gender, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, comorbidities)

Stationary history (hospital stay and postoperative hospital stay)

Perioperative and intraoperative complications

30-day mortality

Results

A total of 21,571 primary LSG were documented in the database of the Institute for Quality Assurance at the Otto-von-Guericke-University in Magdeburg from 2005 to 2016. All complete documented operations were included in the analysis of the two age groups. Of these, 19,799 patients were < 60 years of age (91.8%) and 1772 patients were ≥ 60 years old (8.2%).

Demographic Data

Gender

In both groups (I and II), there was a higher proportion of female patients (66.1% vs. 57.4%). LSG was performed in just 6720 (33.9%) and 755 (42.1%) obese males, respectively (Table 1).

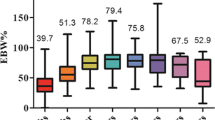

BMI

The BMI values were differentiated according to the age category (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5). The average BMI was 51.7 ± 9.5 kg/m2 (median 50.5 kg/m2) in patients < 60 years. In the age group ≥ 60 years, average BMI was 49.2 ± 8.1 kg/m2 (median 48.2 kg/m2). The difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

ASA classification

In the age group I, 5% were operated on with an ASA I, 41.6% with an ASA II, 51.1% with an ASA III, and 2.4% with an ASA IV. In patients ≥ 60 years, 1.8% had ASA I, 24.5% ASA II, 68.1% ASA III, and 5.7% ASA IV. These differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Statistically, most of the patients who were operated on in the age group < 60 years had an ASA status of grade II and III. In the age group ≥ 60 years, ASA III was predominantly represented. Patients with ASA I and ASA IV were only slightly present in both groups (Table 2).

Comorbidities

Preoperatively, 89.3% of patients of group I and 97.9% of group II suffered from at least one comorbidity. Thus, the prevalence was found to be significantly higher in the second age category (p < 0.001).

Statistically significant between the two age groups (< 60 vs. ≥ 60 years) were the prevalence of hypertension with 60.7% vs. 84.3% of diabetes mellitus type II (DMII): total with 33.4% vs. 59.3%, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus type II (IDDMII) with 10.2% vs. 27.3%, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus type II (NIDDMII) with 18.1% vs. 27%, and on sleep apnea with 25.6% vs. 39.7%, respectively (p < 0.001 each).

In both groups, hypertension was the most frequent concomitant comorbidity followed by type 2 diabetes and sleep apnea. For a better overview, the comorbidities are shown in Table 5.

The prevalence of comorbidities in diet diabetic (p = 0.636) and reflux (p = 0.979) was not statistically significant (Table 3).

Perioperative and Intraoperative Complications

The intraoperative complication rate was 1.6% in the age group I and 2.2% in the age group II; this difference was only slightly statistically significant in unadjusted analysis (p = 0.048) and should thus be discussed carefully.

The overall general postoperative complications were 4.9% among patients < 60 years old and 7.8% in patients ≥ 60 years old, and this was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Significant differences (p < 0.001) were particularly in cardiac, renal, and pulmonary complications.

The specific postoperative complication rate showed no significant difference between the two age groups (p = 0.504).

Hospital Stay

The average hospitalization period in groups I and II was 6.9 and 7.9 days, respectively. The duration of stay in patients of the first mentioned group was therefore 1 day shorter than the other group. At this point, a significant difference between the two age categories was observed (p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Postoperative Hospital Stay

In the age group < 60 years, the mean duration of the postoperative hospital stay was 5.7 days. The patient’s group II remained postoperatively between 1 day and 134 days and on average 6.4 days (Table 5). There was also a significant difference between the groups (p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Mortality

The evaluation of the 30-day mortality rate showed that 99.78% of the patients < 60 years had no mortality. In these patients, 44 deaths (0.22%) were recorded. The mortality among the patients ≥ 60 years was seen in four cases (0.23%) and no death was notified in 99.77%. This difference was statistically not significant (p = 0.977). Thirty-day mortality rate in centers with less than 50 operations per year was 0.27%, in centers between 50 and 100 procedures annually 0.18%, and in centers with a volume of more than 100 operations 0.22% without any significance.

Discussion

The present work contains results of the two age groups (< 60 years/≥ 60 years) after an LSG in the perioperative course, which served as a basis for the description and interpretation. Data analysis was carried out by the Institute for Quality Assurance in Operative Medicine at the Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg [7].

The Swedish Obesity Study (SOS) 2007 demonstrated that a drastic improvement in morbidity, mortality, and quality of life was achieved after bariatric surgery. Accordingly, no person affected by obesity is to be deprived of an operation [8].

Nowadays, the LSG is used on one hand with a BMI > 55 kg/m2 as part of the duodenal switch or single-anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy and on the other hand with a BMI of ≤ 50 kg/m2 as single therapy [9].

In current statistics (2013), the Roux-en-Y-gastric-Bypass (RYGB) (45%) and the LSG (37%) are worldwide the most frequently performed interventions in bariatric surgery. In Europe, the LSG (43%) is the first [10]. In Germany, 39.9% of all bariatric operations were LSG [7].

LSG has spread rapidly because of the short time of surgery by trained surgeons and the technique is easy to handle. On the other hand, the LSG achieved within short time a significant weight reduction compared to other complex methods. This is achieved by the restrictive character of the LSG and the endocrine mechanism of the reduction of the ghrelin because of fundus resection [11].

Thus, the feeling of hunger is suppressed by the low ghrelin level. In addition, gastric emptying is accelerated. This is associated with an increase in glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion, which can help to heal DMTII [12].

The reoperation rate after LSG is 6.8–25%, and this is, in most cases, because of a weight regain or an insufficient weight reduction [13].

Disadvantages of the LSG are the irreversibility of the procedure, weight regain, and the serious complications of the leakage and bleeding from the long staple line. In addition, in the case of extremely high BMI, the LSG can be insufficient, requiring a second, more complex operation in the interval [14].

The mortality rate in LSG is between 0 and 3.2%. Complication rate ranges from 4.8 up to 10% and mainly involves leaks and bleeding [15].

As a result, metabolic surgery in older obese patients (> 60 years) was maintained only in 2.7% of the total interventions in 2005. Conclusion is that surgical therapy is under-represented in this age group and is used to a small extent [3].

Between 65 and 75 years old, 33% of men and 39% of women are affected by obesity [5].

Obesity is therefore found mostly in women, and this prevalence correlated with the gender distribution in our investigation. With 66.1% (< 60 years) and 57.4% (≥ 60 years), women in both age groups were numerically superior to men. Thus, in both age groups, women increasingly decided to undergo surgery by means of sleeve gastrectomy.

Nevertheless, the number of men ≥ 60 years (42.6%) increased by approximately 8.7 percentage points compared to the age group < 60 years (33.9%), so that relatively more men aged ≥ 60 years decided to undergo this surgery.

Regarding the general postoperative complications, which occurred significantly more frequently in the age group ≥ 60 years (p < 0.001), this gives rise to the following interpretation. It is known that men increasingly suffer with increasing age from comorbidities, especially cardiac disorders. In general, cardiac complications occurred significantly more frequently in the age group ≥ 60 years, which can be explained by the increasing male proportion.

LSG as a single therapy is recommended in patients with a BMI ≤ 50 kg/m2 [16]. At this point, the data analysis showed that the mean BMI in the age group ≥ 60 years was 49.2 kg/m2, whereas the age group < 60 years was 51.7 kg/m2. Thus, the younger age group had a greater overweight than the age group ≥ 60 years. In general, it should be noted that a BMI > 45 kg/m2 in combination with type II diabetes mellitus is associated with an insufficient weight loss or a weight regain in patients ≥ 65 years [17].

Fatima et al. compared two extreme age classes (≥ 60 years and ≤ 18 years) in a retrospective study. A low 30-day mortality rate (0.7%) was found in the age group ≥ 60 years, which declared obesity surgery as a safe method in extreme groups [18].

O’Keefe et al. indicated that the 30-day mortality rate in younger patients undergoing bariatric surgery is 0.3% [19]. Furthermore, the study by Moon et al. showed no mortality after LSG, whereas the gastric bypass was associated with the highest mortality rate [6].

In our study, the 30-day mortality was recorded in four cases in the age group ≥ 60 years and in 44 cases in the age group < 60 years without a statistical significance (p = 0.977). The 30-day mortality was thus 0.23% for patients ≥ 60 years and 0.22% for patients < 60 years and shows comparable results with the mentioned studies.

Regarding the study of Moon et al., the deviations can possibly be traced back to the differences in the sample size. Here, Moon et al. included only 73 patients in their study. In our evaluations, 1772 patients ≥60 years and 19,799 patients of the age category < 60 years were included. Moreover, the study of Moon et al. does not distinguish whether the evaluated mortality is in a causal connection with the operation or due to other circumstances.

The intraoperative complications and the specific postoperative complications showed only slight non-significant differences between the age groups (< 60 years/≥ 60 years) (p = 0.048 and p = 0.504). These findings are comparable to the observations of Moon et al. The study found that LSG with 1.4% had the lowest reoperation rate after perioperative complications [6]. In our analysis, the finding was not different. For the patients ≥ 60 years, only 31 cases (1.75%) had a reoperation because of bleeding. Compared to the patients < 60 years, there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.127).

Ritz et al. has published, in one of their studies, an increasing incidence of surgical and non-surgical complications of patients > 60 years. However, these did occur after RYGB [20, 21].

In our review, significant differences between the age groups (p < 0.001) were found in the general postoperative complications. Pulmonary complications in patients ≥ 60 years were the most common with 2.3%. Cardiac complications with 1.2% were followed by renal complications with 0.8%.

Leivonen et al. reported that the early complication rate in elderly patients (> 59 years) is higher, whereas younger patients (< 59 years) showed a higher late complication rate [15].

In our study, more general postoperative complications were detected in the group of patients ≥ 60 years old.

At this point, further insights from the references can be cited. Thus, Mizrahi et al. had published a higher complication rate (32.5%) in patients over 60 years, but this was in just 52 case studies [22].

Spaniolas et al. suggested that there is no difference in early morbidity between LSG and RYGB in patients > 60 years [23].

Moreover, Moon et al. reported that LSG has the lowest rehospitalization rates compared to gastric bypass and gastric banding [6].

The statistically significant difference between the age groups with respect to the general postoperative complications may have a causal link with the hospital stay and the postoperative hospital stay. In both cases, there was a significant difference between age classes (p < 0.001).

The average hospital stay of the patients ≥ 60 years was a day longer. In the postoperative stay, the difference was similar.

Here, it can be assumed that the longer stay time is also related to the increased number of comorbidities in the patients ≥ 60 years. Frequently, these require a larger amount of preoperative examinations, which are associated with a further time consumption and a higher duration of stay.

About the comorbidities, patients of age group II had a high rate of general concomitant diseases. The difference compared to the group I was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Special comorbidities such as hypertension (84.3%), type II diabetes mellitus (59.3%), and sleep apnea (39.7%) were significantly more common in the age group ≥ 60 years. The higher incidence of sleep apnea in patients with BMI > 60 kg/m2 could correlate with the increased frequency of pulmonary complications in this age group.

Similar results were obtained in a retrospective analysis of 197 patients over 60 years old. Here, the comorbidity rate was 85.9% for hypertension, 51% for diabetes, and 48.5% for sleep apnea [19].

Although elderly people have more comorbidities associated with overweight, and thus are suspected of a higher surgical risk, Benotti et al. showed that there is no link between age and complication rates [24].

Apart from the complications, weight reduction is an important indicator of the success of an operation. In a retrospective study, Moon et al. compared three operative procedures over 24 months for weight reduction in the age group > 60 years. The LSG patients positioned themselves with their results for the weight loss between the other two groups (gastric band and gastric bypass). Surprisingly, the difference in weight reduction between SG and gastric bypass was no longer significant after 24 months [6].

Furthermore, Garofalo et al. have shown, by means of a simple regression analysis, that age is not a factor influencing success or failure in weight reduction [17].

Finally, it should be noted that in the present analysis, the sample of patients ≥ 60 years old was 8.2%, in relation to the number of patients < 60 years with 91.8%, which is relatively small. Thus, in the case of small numbers, signifiers can already be achieved by a few differences in patient numbers. On the other hand, effects are partly descriptive, but they are not statistically demonstrable because of the small number of cases.

Conclusions

Globally, the number of obese people, including those over 60 years, is growing steadily. Comparing the two age categories (< 60 years and ≥ 60 years) after a LSG, there was no difference in the short-term mortality and merely showed that patients ≥ 60 years had a higher statistically significant difference in the general postoperative complications than the younger patients. However, the group of ≥ 60 years had higher significant rates of comorbidities than the other group.

Through the medical and surgical advances in bariatric surgery, sleeve gastrectomy can be used as a safe and effective surgical method with acceptable perioperative risk even in elderly patients ≥ 60 years. The present exploratory analysis supposed that the use of LSG is not associated with increased perioperative morbidity and mortality even in patients over 60 years old.

Since sleeve gastrectomy is a relatively new method, further studies are needed to evaluate the long-term outcomes, especially considering the weight reduction and the remission of comorbidities. Extensive multivariable analyses should be conducted. There are still open questions to answer to achieve better outcomes and fewer complications.

References

Lehnert H, Reincke M. Adipositas. Ein zunehmendes Problem. Internist. 2015;56(2):109–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00108-014-3531-9.

Benedix F, Benedix DD, Knoll C, et al. Obesity surgery working group. Are there risk factors that increase the rate of staple line leakage in patients undergoing primary sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity? Obes Surg. 2014;24(10):1610–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1257-3.

Robert M, Pasquer A, Espalieu P, et al. Gastric bypass for obesity in the elderly: is it as appropriate as for young and middle-aged populations? Obes Surg. 2014;24(10):1662–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1247-5.

Statistisches Bundesamt. Bevölkerung Deutschlands bis 2060. 12. koordinierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung 2010: 30.

Quebbemann B, Engstrom D, Siegfried T, et al. Bariatric surgery in patients older than 65 years is safe and effective. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1(4):389–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2005.05.003.

Moon RC, Kreimer F, Teixeira AF, et al. Morbidity rates and weight loss after roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric banding in patients older than 60 years old: which procedure to choose? Obes Surg. 2016;26(4):730–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1824-2.

Stroh C, Köckerling F, Volker L, et al. Obesity surgery working group. Results of more than 11,800 sleeve gastrectomies: data analysis of the German bariatric surgery registry. Ann Surg. 2016;263(5):949–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001559.

Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):741–52. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa066254.

D’Hondt M, Vanneste S, Pottel H, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a single-stage procedure for the treatment of morbid obesity and the resulting quality of life, resolution of comorbidities, food tolerance, and 6-year weight loss. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(8):2498–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-011-1572-x.

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25(10):1822–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1657-z.

Rosenthal RJ. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(1):8–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2011.10.019.

Himpens J, Dobbeleir J, Peeters G. Long-term results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for obesity. Ann Surg. 2010;252(2):319–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e90b31.

Fischer L, Hildebrandt C, Bruckner T, et al. Excessive weight loss after sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2012;22(5):721–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0616-1.

Baltasar A, Serra C, Pérez N, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a multi-purpose bariatric operation. Obes Surg. 2005;15(8):1124–8. https://doi.org/10.1381/0960892055002248.

Leivonen MK, Juuti A, Jaser N, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients over 59 years: early recovery and 12-month follow-up. Obes Surg. 2011;21(8):1180–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-011-0454-6.

Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, et al. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective, double blind study. Ann Surg. 2008;247(3):401–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e318156f012.

Garofalo F, Denis R, Pescarus R, et al. Long-term outcome after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients over 65 years old: a retrospective analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2016.05.020.

Fatima J, Houghton SG, Iqbal CW, et al. Bariatric surgery at the extremes of age. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(10):1392–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gassur.2006.08.014.

O’Keefe KL, Kemmeter PR, Kemmeter KD. Bariatric surgery outcomes in patients aged 65 years and older at an American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Center of excellence. Obes Surg. 2010;20(9):1199–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-010-0201-4.

Ritz P, Topart P, Benchetrit S, Tuyeras G, Lepage B, Mouiel J, Becouarn G, Pattou F, Chevallier JM. Benefits and risks of bariatric surgery in patients aged more than 60 years. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2013.12.012

Robert M, Pasquer A, Espalieu P, et al. Gastric bypass for obesity in the elderly: is it as appropriate as for young and middle-aged populations? Obesity Surg. 2014;24(10):1662–9.

Mizrahi I, Alkurd A, Ghanem M, et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients older than 60 years. Obes Surg. 2014;24(6):855–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1177-2.

Spaniolas K, Trus TL, Adrales GL, et al. Early morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass in the elderly: a NSQIP analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(4):584–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2014.02.010.

Benotti PN, Wood GC, Rodriguez H, et al. Perioperative outcomes and risk factors in gastric surgery for morbid obesity: a 9-year experience. Surgery. 2006;139(3):340–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2005.08.017.

Acknowledgements

The German Nationwide Survey on Bariatric Surgery was supported by the Ministry of Research and Education Germany (BMBF) grant number 01GI1124. The responsible investigator is C. Stroh. We thank all hospitals that actively participated in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The following firms support the GBSR without any relation to their products:

Johnson & Johnson Medical GmbH, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Norderstedt, Germany.

Covidien GmbH, Neustadt/Donau, Germany.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hajer, A.A., Wolff, S., Benedix, F. et al. Trends in Early Morbidity and Mortality after Sleeve Gastrectomy in Patients over 60 Years. OBES SURG 28, 1831–1837 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3110-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3110-6