Abstract

While scholars agree that institutions are critical for enabling and constraining entrepreneurial action, the mechanisms by which institutions shape individual entrepreneurs’ actions remain underdeveloped. Whereas a prior work focuses on the direct and moderating effects of institutions on entrepreneurial action, we propose that institutions also indirectly influence entrepreneurial action through their influence on the mental models of actors. To that end, we theorize an underexplored role of institutions: shaping three socio-cognitive traits (SCT)—opportunity recognition, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and fear of failure—that influence entrepreneurial action. Using GEM data from 735,244 individuals in 86 countries, we test and find evidence that SCTs mediate the relationship between institutions and opportunity entrepreneurship. The social legitimacy of entrepreneurship exerts a weaker direct effect on opportunity entrepreneurship but a stronger indirect effect through the SCT channels relative to pro-market institutions. Our study thus provides more nuanced findings concerning the ways formal and informal institutions, as well as the direct and indirect effects of institutions, enable and constrain entrepreneurial action.

Plain English Summary

Pro-market institutions and favorable societal attitudes do not only create beneficial market conditions for entrepreneurship; they also potentially shape the cognitive characteristics conducive to entrepreneurial action. In a sample of 735,244 individuals in 86 countries from 2002 to 2015, we find that formal and informal institutions increase the socio-cognitive traits that, in turn, increase the propensity for opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship. This reveals that the effects of institutions on individual engagement with entrepreneurship are both direct and indirect, suggesting the importance of policy and culture in shaping the cognitive foundations of the entrepreneurial process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There is widespread acknowledgment that institutions, the formal and informal rules of the game (North, 1991), are an important antecedent to entrepreneurship (Bjornskov & Foss, 2016). However, our understanding of how institutions matter, i.e., the mechanisms by which institutions shape individual entrepreneurial action, remains limited (Dilli et al., 2018). One limiting factor is much of the literature focuses on the “average” effects of institutions, implicitly assuming that entrepreneurs respond in a homogenous fashion to the incentives and constraints created by the institutional environment (Burns & Fuller, 2020). A related concern is that the predominant macro-conceptualization of institutions (Bruton et al., 2010) ignores the micro foundation of institutions, e.g., as manifested in individual cognition (Denzau & North, 1994; Grégoire et al., 2011). This is important because entrepreneurship is an inherently uncertain process undertaken by heterogeneous actors based on subjective judgment (Foss et al., 2019; Shepherd et al., 2007). Yet, while the literature provides considerable validity to the notion that entrepreneurial activity is influenced by the institutional context, we thus far only have a rudimentary account of the interdependence of institutions and cognition in explaining the heterogeneity of entrepreneurial action (Foss et al., 2019; Lucas & Boudreaux, 2020; Lucas & Fuller, 2017; McMullen et al., 2016). Consequently, the “riches” of the multilevel mechanisms by which institutions shape entrepreneurial action remain “untapped” (Kim et al., 2016).

The purpose of this paper is to examine the question how do individuals’ cognitive frameworks mediate the relationship between institutions and entrepreneurial action? To do so, we develop a theoretical model grounded in new institutional economics (NIE), wherein intersubjectively congruent mental models (Denzau & North, 1994) were used to interpret the environment manifest in socio-cognitive traits (SCTs) pertinent to entrepreneurship (Boudreaux et al., 2019). Specifically, we consider the role of three SCTs, opportunity recognition, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and fear of failure, as indirect channels by which formal and informal institutions have heterogeneous and nuanced effects on individual decisions to pursue opportunities through entrepreneurial action.

We test our theoretical model using a sample of 735,244 individuals across 86 countries over the period 2002–2015. Our dataset consists of individual-level adult population surveys from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) matched with country-level data from the Economic Freedom of the World Index (Gwartney et al., 2020) and the World Bank’s development indicators. This panel setup allows for a novel application of multilevel mediation techniques, enabling us to evaluate cognitive pathways by which institutions influence decisions to engage in opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship (OME).

Our study makes several contributions to the institution and entrepreneurship literature. First, whereas existing work has theorized institutions as a moderator of SCT’s influence on entrepreneurial action (Boudreaux et al., 2019; Raza et al., 2018; Wennberg et al., 2013; Wyrwich et al., 2016), socio-cognitive theories affirm that such traits are themselves influenced by institutional context (Nikolaev & Bennett, 2016; Pitlik & Rode, 2016). We advance this literature by considering the role of both formal and informal institutions in fostering entrepreneurship, both directly and indirectly: directly through transactional mechanisms (Foss et al, 2019; McMullen et al., 2008) and indirectly through what we term cognitive mechanisms, viz., by shaping the cognitive frameworks of individuals (Foss et al., 2019; Wennberg et al., 2013). By theorizing how formal and informal institutions serve as antecedents to SCTs, which in turn mediate the relationship between institutions and OME, our study responds to Grégoire et al.’s (2011) call to explore the antecedents of entrepreneurial cognition and its operation across levels of analysis. It also addresses Boudreaux et al. and’s (2019, p. 193) suggestion of a mediation model as a complement to extant moderation theories. As such, we advance from the question of which institutions influence entrepreneurial action to how.

Second, and relatedly, our theoretical connection of mental models to SCTs helps bolster the link between NIE and entrepreneurial action theory. NIE scholars generally view “shared” mental models as a convergent result of social interaction, by which individuals’ subjective assessments of institutional and market phenomena cohere to facilitate economic coordination. However, how these elements fit with the multiple aspects of the cognitive process leading to entrepreneurial action is rarely articulated (Grégoire et al., 2011; McMullen & Shepherd, 2006). To that end, we position opportunity recognition as a “third-person” SCT related to perceptions of the market, and fear of failure and entrepreneurial self-efficacy as “first person” SCTs relating the individual to potential action. Our theory thus lays important groundwork for future processual research to elaborate on the intertemporal relation of institutions and cognition as entrepreneurial action unfolds (Bjørnskov et al., 2022; Long et al., 2022; Wood et al., 2021).

Finally, we offer methodological advances by leveraging emerging econometric techniques for multilevel mediation that open many new opportunities for the institution and entrepreneurship literature. Whereas scholars have increasingly theorized that institutional context shapes entrepreneurial cognition (Foss et al., 2019; McMullen et al., 2016), methodological tools to investigate the resulting mechanisms have been lacking or underutilized. The correlated random effects approach (Chamberlain, 1982; Mundlak, 1978) we implement offers a practical path to exploring the pathways by which macro-level contextual variables have effects that are mediated through micro-level, actor-specific characteristics (Boudreaux et al., 2021b).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents our theoretical framework and develops our hypotheses. Section 3 describes our data and methods. Section 4 presents the results, and Section 5 discusses the implications of our work.

2 Theoretical framework

To orient our theory, we present a multilevel model of institutions and entrepreneurial action in Fig. 1. Formal and informal institutions are at the “external” macro level, external to the actor. Meanwhile, cognitive systems manifest at the individual level through mental models, viz., SCTs. Formal and informal institutions shape the physical conditions amenable to entrepreneurship (easing access to resources, reducing uncertainty and risk of expropriation), i.e., transactional mechanisms. However, they also shape the evolving mental models that emerge among individuals in a society, what we label cognitive mechanisms. Our model suggests institutions influence entrepreneurial action through both types of mechanisms.Footnote 1 As scaffolding for our theoretical model, we first develop baseline hypotheses on the direct relationships between (1) SCTs and entrepreneurship and (2) the institutional environment and entrepreneurship based on established theory. We then use these for the development of our multilevel mediation model.

2.1 Social cognition and entrepreneurial action

Entrepreneurship is an experimental decision-making process wherein actors combine heterogeneous assets within a firm to produce goods and services that they believe will satisfy consumers’ wants better than the next best alternatives. This process takes place in a market setting characterized by uncertainty, resource heterogeneity, and agents with cognitive limitations and dispersed knowledge (Foss et al., 2019). In turn, the “agency” underpinning venture creation “arises, ultimately, from the actions of particular persons” (Baron, 2004, p. 224), as entrepreneurs act upon their subjective assessments about the present and future state of resources, technologies, and consumer preferences (Foss & Klein, 2012; Foss et al., 2019).

The rich literature examines how cognition influences the individual decision-making processes that culminate in new venture creation (Mitchell et al., 2002). This cognitive perspective encompasses a range of mental constructs (Grégoire et al., 2011). In particular, mental processes are generally viewed as the “cognitive mechanisms through which we acquire information, enter it into storage, transform it, and use it to accomplish a wide range of tasks” (Baron, 2004, p. 221). Entrepreneurial actors use these processes to “make assessments, judgments, or decisions involving opportunity evaluation, venture creation, and growth”( Mitchell et al., 2002, p. 97). In turn, knowledge, motivation, beliefs, and doubts play an influential role in determining an individual’s decision to pursue entrepreneurial action (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006; Shepherd et al., 2007). As Busenitz & Lau, (1996, p. 26) succinctly state, the “propensity to engage in entrepreneurial activity is a function of cognition.”

We focus on three socio-cognitive traits (SCTs) that have been identified as important determinants of individual entrepreneurial action: (1) opportunity recognition, (2) entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and (3) fear of failure (Boudreaux et al., 2019; Minniti & Nardone, 2007; Wood & Bandura, 1989). In so doing, we advance the literature by mapping these SCTs to the cognitive stages outlined in entrepreneurial action theory. The entrepreneurial action theory views the decision to bear uncertainty by engaging in entrepreneurial action as the result of the recognition that an opportunity “exists,” i.e., a third-person opportunity, and the evaluation of that opportunity “for oneself,” i.e., a first-person opportunity (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006; Shepherd et al., 2007). As such, we view opportunity recognition as a third-person SCT, reflecting traits whereby individuals are prone to believe in the presence of a “potential opportunity for someone in the marketplace” (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006, p. 137). It is readily evident that opportunity recognition is a key determinant of entrepreneurial action and at the core of modern theories of entrepreneurial action (Baron, 2006, 2007), as the perception of new business opportunities is a critical first step in the venture creation process (Kirzner, 1973).

However, recognition is a necessary but insufficient condition for entrepreneurial action (Baron, 2007). To that end, entrepreneurial action requires that an “entrepreneur must overcome doubt by forming a first-person opportunity belief, which is a belief that the opportunity is of value and achievable by him or her” (Shepherd et al., 2007, p. 76). A belief that opportunities exist does not imply that an individual believes they possess the requisite knowledge and motivation necessary to exploit those favorable market conditions. As such, we view entrepreneurial self-efficacy and fear of failure as first-person SCTs, reflecting an individual’s beliefs about their entrepreneurial knowledge, skills, and doubts regarding the potential outcomes of perceived entrepreneurial opportunities for them.

The literature also provides clear evidence that these first-person SCTs shape decisions to engage in entrepreneurial action. Strong self-efficacy beliefs are positively correlated to people’s intentions to engage in entrepreneurial action and the amount of effort individuals invest in developing critical competencies necessary to accomplish challenging tasks (Baron, 2007; Wood & Bandura, 1989). Not surprisingly, meta-analytic studies suggest that entrepreneurial self-efficacy is strongly correlated with entrepreneurial engagement (Rauch & Frese, 2007). Finally, fear of failure provokes an unpleasant emotional reaction (e.g., grief, shame, or self-blame) that can significantly impede entrepreneurial action. When an individual perceives failure in a negative way, they will actively try to avoid it (Shepherd, 2003). Numerous studies suggest that fear of failure can discourage people from engaging in entrepreneurial activities (Boudreaux et al., 2019; Caliendo et al., 2009). In sum, the well-established links between these first- and third-person SCTs and entrepreneurial action inform our first set of baseline hypotheses:

-

H1a: opportunity recognition is positively associated with opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship.

-

H1b: entrepreneurial self-efficacy is positively associated with opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship.

-

H1c: fear of failure is negatively associated with opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship.

2.2 Transactional mechanisms: institutions and entrepreneurship

The cognitive perspective above recognizes that human action “proceeds from complex interactions between the environment and the mind” (Grégoire et al., 2011, p. 1446). It is clear that entrepreneurial cognition is environmentally situated (Bouchikhi, 1993), suggesting that entrepreneurial action emerges from actors’ interpretation of the environmental elements they observe (Davidsson, 2015). This suggests that the decision to undertake the new venture creation process depends on how an entrepreneur perceives market conditions in relation to the institutional environment (Baron, 2006; Busenitz & Lau, 1996; Mitchell et al., 2000). As such, entrepreneurial cognition is not institutionally antiseptic but rather is situated in a particular institutional context (Bjornskov & Foss, 2016; Boudreaux, 2017; Terjesen et al., 2016).

Institutions are the “humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic, and social interactions” (North, 1991, p. 97). A society’s institutions consist of both the formal (e.g., economic, legal, and political) and informal (e.g., cultural norms, values, and beliefs) rules that define the scope of permissible behavior in economic, political, and social affairs. Institutions, therefore, enable and constrain economic activity, including entrepreneurship (Baumol, 1990; North, 1991). Research on institutions and entrepreneurship tends to focus on what we call transactional mechanisms, i.e., effects on the costs and uncertainty associated with the myriad transactions (exchanges) involved in entrepreneurial venturing (McMullen et al., 2008). It is clear that institutions enable entrepreneurial action through transactional mechanisms, e.g., lowering the costs of market exchange, reducing barriers to entry and growth, increasing the quality of governance, and empowering cultural norms that promote peaceful interaction (Foss et al., 2019). These transactional mechanisms pertain to the external environment that individuals venture within, shaping market conditions like supply and demand (Bruton et al., 2010), providing incentives for different types of entrepreneurial activities (Baumol, 1990; Boudreaux et al., 2018), and influencing the level of market uncertainty (Foss et al., 2019; McMullen et al., 2008).

Much of the literature considers either the formal or informal institutional environment, but a growing number of studies suggest that it is important to consider the effects of both the formal and informal institutional environments on entrepreneurial activity (Bennett & Nikolaev, 2021a; Eesley et al., 2018; Li & Zahra, 2012). In turn, we focus on both formal institutions as pro-market institutions that support market activity and limit government interference in the economy (Bennett & Nikolaev, 2021a; Dau & Cuervo-Cazurra, 2014; Holcombe & Boudreaux, 2016), and informal institutions as social legitimacy of entrepreneurship (Busenitz et al., 2000; Etzioni, 1987), or the “subjective norms or commonly held perceptions regarding the status and rewards of entrepreneurship in a given population” (Stephan & Uhlaner, 2010, p. 1349). A growing body of evidence suggests that strong pro-market institutions enable entrepreneurial activity by reducing uncertainty in exchange and lowering transaction costs, while weak pro-market institutions constrain by elevating uncertainty and the transaction costs facing potential entrepreneurs (Bennett, 2020; Bennett & Nikolaev, 2021a; Bjørnskov & Foss, 2013; Dau & Cuervo-Cazurra, 2014; Foss et al., 2019; McMullen et al., 2008; Nikolaev et al., 2018). Similarly, the literature links stronger social legitimacy of entrepreneurship, reflecting societal approval and celebration of entrepreneurship as an occupational choice, to greater entrepreneurship by increasing the potential rewards associated with becoming an entrepreneur as well as access to key resources (Hindle & Klyver, 2007; Kibler et al., 2014; Wyrwich et al., 2016). In sum, an extensive body of research affirms that both pro-market institutions and the social legitimacy of entrepreneurship are important antecedents to individuals’ pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities (Bennett & Nikolaev, 2019; Bjornskov & Foss, 2016; Terjesen et al., 2016). Thus, our baseline institutional hypotheses are the following:

-

H2a: Stronger pro-market institutions are positively associated with opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship.

-

H2b: Greater social legitimacy of entrepreneurship is positively associated with opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship.

2.3 Cognitive mechanisms: the role of socio-cognitive traits

As described above, the extant literature establishes that institutions have direct effects on entrepreneurial action through transactional mechanisms that shape market conditions. However, a subjectivist view of entrepreneurial cognition affirms that the transactional mechanisms of institutions for entrepreneurship are only part of the story (Foss et al., 2008). Beyond the direct effects of institutions on entrepreneurship, institutions also shape entrepreneurial action via their effects on individuals’ cognition. Because cognition is subjective, institutions also face the challenge of divergent expectations. Hence, “transactional” benefits are only realized to the extent that convergent expectations result in intersubjective agreement, i.e., a common understanding of the meaning of institutional rules and the behaviors that others will or will not engage in, given those rules (Greif & Mokyr, 2017). This is suggestive of a second set of mechanisms, what we label cognitive mechanisms, related to the nature of convergent beliefs about the institutional and market environments.

Although scholars rarely explore such cognitive mechanisms, they are not without precedent in NIE. In fact, one of the intellectual founders of NIE, Douglass North, offered a sophisticated take on the relationship between the objective rules of the game and the subjective perceptions of individual actors that accounts for the possibility of cognitive mechanisms. As Denzau & North, (1994, p. 4) write,

“To understand decision-making under such conditions of uncertainty, we must understand the relationship between the mental models that individuals construct to make sense out of the world around them, the ideologies that evolve from such constructions, and the institutions that develop in a society to order interpersonal relationships” (emphasis added).

As indicated, mental models are the cognitive structures through which individuals make sense of their environment, giving rise to values and beliefs (viz., ideology) that inform subjective expectations and judgments pertaining to various courses of action. While often relegated to the background of NIE-based entrepreneurship scholarship, Denzau and North’s framework offers an important, integrated theory of the relationship between cognition, institutions, and entrepreneurial action. Namely, “mental models are the internal representations that individual cognitive systems create to interpret the environment, and the institutions are the external (to the mind) mechanisms individuals create to structure and order the environment” (Denzau & North, 1994, p. 4). This dovetails neatly with the literature on entrepreneurial cognition, which is concerned with “understanding how entrepreneurs use simplifying mental models to piece together previously unconnected information that helps them to identify and invent new products or services, and to assemble the necessary resources to start and grow businesses” (Kuratko et al., 2020, p. 3).

Despite the acknowledged importance (and interdependence) of institutions and cognition in entrepreneurship (Foss et al., 2019), how the mental processes pertinent to entrepreneurship are shaped by institutions remains underexplored. Scholars typically theorize in relation to the transactional mechanisms of institutions when synthesizing cognitive and institutional elements. For instance, several papers suggest that the relationship of SCTs to entrepreneurial action is moderated by institutional effects in the environment (Boudreaux et al., 2019; Kibler et al., 2014; Wennberg et al., 2013; Wyrwich et al., 2016). In these accounts, given SCTs are expressed across institutional environments, they have the strongest effects on entrepreneurial action in those institutional environments that create favorable “objective” conditions for entrepreneurship (Mitchell et al, 2000; Raza et al., 2018). As such, the institutional environment creates market conditions that are amenable to actions that might follow from SCTs.

However, there is also a theoretical basis for suggesting that institutions shape entrepreneurial action through cognitive mechanisms. One such basis derives from information processing theory, which describes the cognitive mechanisms involved when an individual responds to an environmental stimulus by taking action (Fiske & Taylor, 2013). The information processing theory suggests that the path from “input” received from the institutional environment to “output” in the resulting entrepreneurial action is mediated by “innate propensities and abilities of the mind” (Grégoire et al., 2011, p. 1447). In turn, Foss et al., (2019, p. 1202) note that “institutions not only supply (monetary incentives) but also influence cognition” (emphasis added). As they elaborate: “institutions do not just regulate behaviors by imposing direct constraints on entrepreneurial conduct…They also provide frameworks and cognitive categories that may influence entrepreneurial judgment” (Foss et al., 2019, p. 1209). This suggests that institutions can partly shape (or at least influence) the mental models of individuals in society by promoting the expression of certain SCTs over others.

Building on these insights, we propose that SCTs mediate the relationship between the external institutional environment and entrepreneurship (Lim et al., 2010). Specifically, individuals’ SCTs can be understood as reflecting variation in mental models created for the purpose of interpreting the formal and informal institutional environments. Rather than viewing SCTs as characteristics determined independently from the institutional context, our conceptualization suggests that SCTs are themselves partially institutionally determined. This opens intriguing possibilities about the dual roles (and relative importance) of transactional and cognitive mechanisms by which institutions shape entrepreneurial action.

2.3.1 Pro-market institutions, socio-cognitive traits, and entrepreneurship

To further elaborate on the transactional and cognitive mechanisms outlined above, we first consider how pro-market institutions might influence individuals’ SCTs. Pro-market institutions are often conceptualized as the philosophically consistent and multi-dimensional concept of economic freedom (Bennett & Nikolaev, 2021a; Dau & Cuervo-Cazurra, 2014), which is characterized by the principles of “personal choice, voluntary exchange, freedom to compete, and protection of person and property” (Gwartney & Lawson, 2003, p. 406). We thus ground our theory in the established relationship between economic freedom and individual choice (Hayek, 1973; Nikolaev & Bennett, 2016). Economic freedom imposes few constraints on how individuals allocate their time and resources while shifting the “consequences” of action onto the individual (Hayek, 1945). As a result, individuals tend to “freely choose, learn, innovate, and exert control over their environment” (Nikolaev & Bennett, 2016, p. 40). We suggest individuals cognitively adapt to this expansion of individual choice and control (Pitlik & Rode, 2016).

The literature provides one clear mechanism by which pro-market institutions facilitate the third-person SCT of opportunity recognition: by availing a broader range of market opportunities to be recognized (Bjørnskov & Foss, 2013). In countries with stronger pro-market institutions, individuals face fewer institutional barriers to entry as well as lower transaction costs associated with experimentation of heterogeneous resource combinations, searching for suppliers, bargaining over prices, and monitoring the production process (Foss et al., 2019). Entrepreneurs also face lower risks that their property will be expropriated or their contracts be rendered unenforceable (McMullen et al., 2008).This lengthens the time horizon of viable projects, facilitating venture plans that require a longer-run view (Bennett et al., 2022). In turn, we expect that pro-market institutions also inform individuals’ tendency toward alertness to entrepreneurial opportunities. Because pro-market institutions make entrepreneurship a more desirable career choice for many (Gohmann, 2012), it increases the effort individuals allocate toward scanning the environment for opportunities to earn a profit by serving a previously unmet consumer demand (Foss et al., 2019). As such, improvements in pro-market institutions over time should increase entrepreneurs’ opportunity perceptions (Audretsch & Fiedler, 2021). This logic, combined with the well-established positive relationship between opportunity recognition and entrepreneurial action, motivates the following multilevel mediation hypothesis:

-

H3a: Individuals living in a country that has experienced an increase in pro-market institutions over time are more likely to recognize perceived business opportunities, which in turn is associated with a higher likelihood of pursuing opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship.

We also expect pro-market institutions to positively influence individuals’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Going beyond the economic processes by which individuals cognitively adapt to the favorable conditions associated with pro-market institutions, this first-person SCT positions an individual’s self-assessment relative to their environment. Pro-market institutions promote a sense of control, wherein individuals believe that their own decisions inform their outcomes (Nikolaev & Bennett, 2016; Pitlik & Rode, 2016). In turn, a greater sense of control has been shown to increase self-efficacy in general (Phillips & Gully, 1997). When people believe that social and economic rewards are a function of their efforts and actions, they tend to “pursue the type of lives that they value the most while maximizing their autonomy and developing their talents” (Nikolaev & Bennett, 2016, p. 40). As Phillips & Gully, (1997, p. 792) write, “self-efficacy is thought to reflect both an individual’s self-perceived ability and a motivational component defined by Kanfer, (1987, p. 260) as ‘intentions’ for effort allocations.’” Stable pro-market institutions reduce the cognitive bandwidth that entrepreneurs must allocate toward mitigating risks associated with arbitrary and unexpected changes in the institutional environment (Bennett et al., 2022; Bylund & McCaffrey, 2017), thereby providing more time and incentive for individuals to invest in their own human capital and entrepreneurial skill development (Feldmann, 2017). By providing greater security of private property rights and enforcement of contracts, pro-market institutions reduce the uncertainty of exchange and provide individuals with greater confidence that they will earn a return by investing their skills, talents, and resources in an entrepreneurial venture (McMullen et al., 2008). For these reasons, therefore, pro-market institutions instill greater entrepreneurial self-efficacy. This logic, combined with the well-established positive relationship between self-efficacy and entrepreneurial action, motivates our second multilevel mediation hypothesis:

-

H3b: Individuals living in a country that has experienced an increase in pro-market institutions over time are more likely to exhibit entrepreneurial self-efficacy, which in turn is associated with a higher likelihood of pursuing opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship.

Finally, while pro-market institutions provide entrepreneurs with the freedom to enter and compete in markets, it also offers them the freedom to fail when offering goods and services that are rejected by consumers. This is reflected in the finding that pro-market institutions tend to be associated with greater dynamism in terms of both business creation and failure (Barnatchez & Lester, 2017; Bennett, 2020, 2021). However, while pro-market institutions do not shield entrepreneurs from failure, given inherent market uncertainty (Foss et al., 2019; McMullen & Shepherd, 2006), they are more tolerant of and reduce the costs associated with entrepreneurial failure (Bennett, 2021; Clark & Lee, 2006). Furthermore, pro-market institutions provide “more alternative chances to redeploy and recoup investments in entrepreneurial expertise and capital” following venture failure (Dutta & Sobel, 2021, pp. 1–2). Relatedly, Bjørnskov & Foss, (2013) note that the “elasticity of substitution” in an economy, reflecting the ease with which resources can be reallocated across activities toward higher-valued uses, is increasing with the level of pro-market institutions. Hence, even while pro-market institutions create a more competitive, dynamic environment where failure may be common, we suggest individuals are less likely to fear these outcomes in the event of venture failure or underperformance. Thus, pro-market institutions reduce fear of failure among entrepreneurs by reducing the potential loss of dignity, time, and resources invested. This logic, combined with the well-established negative relationship between fear of failure and entrepreneurial action, motivates the following multilevel mediation hypothesis:

-

H3c: Individuals living in a country that has experienced an increase in pro-market institutions over time are less likely to exhibit fear of failure, which in turn is associated with a higher likelihood of pursuing opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship.

2.3.2 Social legitimacy of entrepreneurship, socio-cognitive traits, and entrepreneurship

We also expect the social legitimacy of entrepreneurship, our informal institution of interest, to facilitate mental processing amenable to entrepreneurial action via the manifestation of opportunity recognition, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and reduced fear of failure. For this, we begin with the insight that social norms tend to structure societal rewards to certain actions, and that individuals adapt to these reward structures (Ellickson, 2021).

First, we argue that the social legitimacy of entrepreneurship will positively influence opportunity recognition as a third-person SCT, positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship as a legitimate and desirable pursuit in society will tend to increase individuals’ alertness to opportunities. One pertinent reason is the effect of salient, desirable conceptions of “ideal types” on information processing (McMullen, 2017). When entrepreneurship is viewed more favorably, various stakeholders (e.g., customers, suppliers, or governments) are also more likely to perceive entrepreneurs as legitimate and, in turn, more likely to engage in positive transactions with them. This can enhance access to various resources that can remove constraints and facilitate entrepreneurial decision-making. For instance, research on entrepreneurial intentions demonstrates individuals are more inclined to view entrepreneurship as a desired path when they enjoy stronger social and environmental support for entrepreneurial activity (Meoli et al., 2020; Nikolaev & Wood, 2018). This can further legitimize entrepreneurial pursuits, reducing the uncertainty that potential entrepreneurs face and motivating them to look for business opportunities, boosting entrepreneurial alertness. As an increasing number of people believe that it is socially desirable to pursue business ideas and observe positive entrepreneur role models in the media, this also can drive up alertness, signaling that there are myriad instances of successful innovation “out there” (Hindle & Klyver, 2007). This logic, combined with the well-established positive relationship between opportunity recognition and entrepreneurial action, motivates the following multilevel mediation hypothesis:

-

H4a: Individuals living in a country that has experienced an increase in social legitimacy of entrepreneurship over time are more likely to recognize perceived business opportunities, which in turn is associated with a higher likelihood of pursuing opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship.

Turning again to the first-person SCTs, we suggest entrepreneurial self-efficacy will also mediate the relationship between the social legitimacy of entrepreneurship and an individual’s opportunity-motivated entrepreneurial action. When entrepreneurial “success” is not only celebrated but also “amplified” by the media, entrepreneurship will be perceived as a more desirable career choice (Wyrwich et al., 2016). This can intensify feelings of self-worth and purpose when people engage in entrepreneurial activities (Stephan et al., 2020). Such dynamics can further increase entrepreneurial self-efficacy; after all, one only needs a garage and a new idea to start the next big company (Audia & Rider, 2005). Organizational-level research also shows that more supportive social environments tend to promote experimentation “without fear of appraisal, and frequent and open exchange of feedback” (Choi et al., 2003, p. 360), which further increases self-efficacy beliefs (Stephan & Uhlaner, 2010). This logic, combined with the well-established positive relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial action, motivates the following multilevel mediation hypothesis:

-

H4b: Individuals living in a country that has experienced an increase in social legitimacy of entrepreneurship over time are more likely to exhibit entrepreneurial self-efficacy, which in turn is associated with a higher likelihood of pursuing opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship.

Finally, societies that favor entrepreneurial endeavors are more likely to perceive failure as an acceptable outcome from the process of starting a new venture. Wyrwich et al., (2016, p. 473) find significantly higher fear of failure among individuals in East Germany, where “anti-capitalist indoctrination in socialism [led] to the formation of norms and values that are at odds with entrepreneurship” (ibid., p. 473), than among individuals in West Germany where this was not the case. While they do not take the next step to model the implications for opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship, it is natural to connect these findings to the work mentioned above on fear of failure as a hindrance to entrepreneurship (Caliendo et al., 2009).

In contrast, in many cases where entrepreneurship enjoys high social legitimacy, failure is not only accepted but even celebrated. For example, one of the most prominent mantras of Silicon Valley, the global center for high technology and innovation, is “fail fast, fail often”. In such environments, entrepreneurs praise their mistakes and laud the virtues of failure, indeed, “if you cannot fail, you cannot learn” (Ries, 2011, p. 56). This camaraderie around failure reflects shared mental models that promote an entrepreneurial culture while encouraging people to overcome their natural fear of failure (Hayton & Cacciotti, 2013). Furthermore, observing successful entrepreneurs reduces fear of failure while observing business failure increases fear of failure (Wyrwich et al., 2019), such that the instances of entrepreneurship that societies emphasize serve as “environmental stimuli that are apprehended as threats in achievement” (Cacciotti & Hayton, 2015, p. 181). Because media coverage in societies that foster acceptance of entrepreneurship tends to be overwhelmingly positive, often consisting of sensational stories of successful entrepreneur role models, individuals are much less likely to experience a threat appraisal and hence fear of failure (Hunter et al., 2020). Extraordinary success stories are also easier to recall and more likely to weigh heavily into people’s judgments, further decreasing fear of failure and promoting the search for new venture opportunities (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). This logic, combined with the well-established negative relationship between fear of failure and entrepreneurial action, motivates the following multilevel mediation hypothesis:

-

H4c: Individuals living in a country that has experienced an increase in social legitimacy of entrepreneurship over time are less likely to exhibit fear of failure, which in turn is associated with a higher likelihood of pursuing opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship.

3 Data and methods

The data for our analysis is from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) Adult Population Survey (APS), which surveys a minimum of 2,000 individuals in dozens of countries on an annual basis. We merged this database with the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World Index (Gwartney et al., 2020). After deleting missing observations, our analysis is based on a sample of 735,244 individuals from 86 countries spanning the period 2002–2015. Table 1 provides descriptions, data sources, and summary statistics for the variables used in the analysis, and Table 2 provides a correlation matrix. In the supplementary online appendix, we report the individual sample size by country and year in Appendix Table 7.

3.1 Dependent variable: entrepreneurial action

We operationalize entrepreneurship following the convention used in GEM: “an attempt at a new business or new venture creation, such as self-employment, a new business organization, or the expansion of an existing business” (Reynolds et al., 2005, p. 223). Following recent work (Boudreaux & Nikolaev, 2019; Boudreaux et al., 2019), we focus on opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship (OME) as our dependent variable. Specifically, GEM asks individual respondents if they are involved in total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA). If they respond “yes,” they are then asked to clarify whether their motivation is to take advantage of a business opportunity or out of necessity (GEM codes the former as TEA-OPP). Hence, this variable is binary-coded (1 = involved in OME, 0 = not involved in OME) and reflects first-person entrepreneurial action taken on a perceived business opportunity (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006).Footnote 2

3.2 Independent variables: institutions

3.2.1 Pro-market institutions

Following a growing body of entrepreneurship studies (Bennett & Nikolaev, 2019, 2021a; Bjørnskov & Foss, 2013; Boudreaux & Nikolaev, 2019; Boudreaux et al., 2019; Gohmann, 2012), we use the Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) index (Gwartney et al., 2020) as our measure of pro-market institutions, which is comprised of five areas: (1) government size, (2) legal system and property rights, (3) sound money, (4) freedom to trade internationally, and (5) regulation.

3.2.2 Social legitimacy of entrepreneurship

Our measure of informal institutions is the social legitimacy of entrepreneurship, which reflects the “degree to which a country’s residents admire entrepreneurial activity” and view entrepreneurship as a desirable career path (Busenitz et al., 2000, p. 995; Etzioni, 1987). Specifically, we follow Stenholm et al. (2013) in using two variables from the GEM dataset, new business status (“entrepreneurial status”) and new business media (“media attention”), as our measure of social legitimacy of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial status captures whether respondents believe entrepreneurs have a high status in society (“those successful at starting a business have a high level of status and respect”). Media attention captures whether respondents believe the media portrays entrepreneurs in a positive light (“you will often see stories in the public media about successful new businesses”). Each variable represents the proportion of the sample population that agrees with the underlying statement. We assessed whether these two variables measure a single underlying latent factor using Cronbach’s alpha. The construct’s alpha (0.70) satisfies the common accepted 0.70 threshold. It is also consistent with theory and uses the same variables from the literature (Stenholm et al., 2013).

3.3 Socio-cognitive traits

The “propensity to engage in entrepreneurial activity” is ultimately a function of individual cognition or the thought structure and process that leads to the decision to engage in entrepreneurial action (Busenitz & Lau, 1996, p. 25). Following recent research, we operationalize entrepreneurial cognition using individual responses to a set of three binary questions from the GEM survey (Aragon-Mendoza et al., 2016; Boudreaux et al., 2019; Raza et al., 2018). First, we measure fear of failure using the GEM variable fearfail (1 = if an individual indicates that failure might prevent them from starting a business, 0 = otherwise). Second, we measure opportunity recognition using the GEM variable opport (1 = if an individual perceives in the next 6 months there will be good opportunities to start a business, 0 = otherwise). Third, we measure entrepreneurial self-efficacy using the GEM variable suskil (1 = if an individual believes he or she has the knowledge, skills, or experience required to start a business, 0 = otherwise).

3.4 Control variables

We include control variables at the individual and country levels to mitigate potential omitted variable bias. The entrepreneurship literature has identified many different antecedents of entrepreneurship activity (Nikolaev et al., 2018). At the individual level, we control for education, gender, age and its quadratic, and household income. Education, operating as human capital, is an important determinant of entrepreneurship activity. Education is important in the occupational choice model where individuals can switch between wage-employment and self-employment (Gohmann, 2012). Education might serve as a proxy for ability and thus gauge the extent to which individuals have greater managerial ability and identify new venture opportunities (Simoes et al., 2016). However, education might also increase one’s opportunity cost in the labor market, which discourages self-employment (Van Der Sluis et al., 2008). We use the GEM measure, gemeduc, which is binary coded (1 = the individual has completed secondary education, 0 = otherwise).

We also control for the respondent’s gender since gender issues have been shown to be critical to the decision to become an entrepreneur (Minniti & Nardone, 2007). Gender is binary coded (1 = female, 0 = male). Next, we control for the respondent’s age. We expect the decision to become an entrepreneur increases with age, but studies suggest this positive effect diminishes through the entrepreneurial life cycle (Lévesque & Minniti, 2011). Age is measured as a continuous variable for the entrepreneur’s age and as a quadratic term to account for this non-linearity. Lastly, we control for income at the individual level. The literature has identified financial capital, which can ease liquidity constraints, as an important antecedent of entrepreneurship activity (Boudreaux & Nikolaev, 2019; Boudreaux et al., 2021a, 2021b). The GEM survey asks respondents about their household income according to terciles for each country. Household income is binary coded (1 = individual is classified as high income, 0 = otherwise). At the country level, we follow a convention in controlling for the level of economic development using the log of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita at purchasing power parity (Bennett et al., 2017; Boudreaux et al., 2019; Stephan & Uhlaner, 2010; Wennberg et al., 2013).

3.5 Sample discussion

In our sample, about 50% of the countries experienced an increase in pro-market institutions over time, 22% experienced a decrease, and 28% experienced little to no change (or were included in our sample only once). For social legitimacy of entrepreneurship, these percentages are 33, 42, and 26%, respectively. Many of the increases or decreases were relatively small, which is somewhat expected given the infrequent nature of institutional change (Roland, 2004; Williamson, 2000). There were, however, some notable changes.

Iceland, for example, experienced a large decrease in pro-market institutions between 2003 and 2010, declining from 8.11 to 6.56, a period overlapping with the Icelandic financial crisis (2008–2011). Meanwhile, Croatia, Malaysia, and Romania all experienced large increases in pro-market institutions during our sample period. Croatia’s score increased from 6.28 in 2003 to 7.31 in 2015, Malaysia’s score increased from 6.30 in 2003 to 7.49 in 2015, and Romania’s score increased from 6.56 in 2003 to 7.91 in 2015.

India and Latvia experienced significant declines in the social legitimacy of entrepreneurship during our sample period. India’s score decreased from 0.770 in 2006 to 0.474 in 2015, and Latvia’s score decreased from 0.736 in 2005 to 0.563 in 2015. Meanwhile, Portugal and Romania experienced significant increases in the social legitimacy of entrepreneurship. Portugal’s score increased from 0.475 in 2004 to 0.673 in 2015, and Romania’s score increased from 0.467 in 2007 to 0.703 in 2015. Future work might examine these countries in more detail to help understand the causes and consequences of these institutional changes.

3.6 Methods

3.6.1 Correlated random effects

Due to the nested nature of our dataset, we use a correlated random effects (CRE) multilevel approach to test our hypotheses (Wooldridge, 2019). Moreover, because our dependent variable, OME, is binary coded, we use a logistic regression estimator. In the case of limited dependent regression models, it is well known that the traditional fixed effects estimator provides biased and inconsistent parameter estimation (i.e., the “incidental parameters problem”) (Neyman & Scott, 1948). In contrast, the CRE approach provides an unbiased and consistent estimation of key parameters.Footnote 3 Following Mundlak, (1978), the CRE approach involves including the cluster means of each explanatory variable in the model as additional control variables (Schunck, 2013).Footnote 4 Consider Eq. (1),

where subscript i denotes individuals, j denotes clusters (i.e., groups of countries), and t denotes year. \({x}_{ijt}\) is a vector of variables believed to influence our dependent variable, \({y}_{ijt}\), and \({\varepsilon }_{ijt}\) is the idiosyncratic disturbance term. The cluster mean, \({\overline{x} }_{j}\), picks up any correlation between this variable and the cluster-level. Importantly, \({\beta }_{1}\) is a “fixed effect” estimate identical to those obtained from the within-transformation (i.e., demeaning) and least squares dummy variable (LSDV) linear model approaches (Schunck, 2013), allowing for us to estimate the effect of within-country institutional changes. However, there is an important advantage to the CRE method for our purposes: for nonlinear models such as logit, probit, and tobit, the other two approaches provide inconsistent estimation of fixed effects parameters, while the CRE approach provides consistent parameter estimation (Wooldridge, 2019). Because our dependent variable is binary, we use logistic regression; hence, we use CRE to obtain consistent average partial effects.Footnote 5Footnote 6

3.6.2 Mediation

We now report our strategy for testing our hypotheses that institutions affect entrepreneurship both directly and indirectly through SCTs. To test the hypothesis that institutions exert a direct and positive effect on OME, we examine the following logistic regression model:

where \({F}_{jt}\) denotes the measure of formal institutions, \({I}_{jt}\) denotes informal institutions, and \({\overline{F} }_{j}\) and \({\overline{I} }_{j}\) are their cluster means. Here, \({\beta }_{2}\) and \({\beta }_{3}\) are the partial effects of formal institutions and informal institutions on OME, and we hypothesize \({\beta }_{2}\) > 0 and \({\beta }_{3}\)> 0. To test the hypothesis that institutions have an indirect effect on OME through SCTs, we follow Baron & Kenny, (1986) and augment Eq. (2) with SCTs, our mediating variables:

where \({S}_{ijt}\) denotes a matrix of SCTs (fear of failure, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, or opportunity recognition), \({\overline{S} }_{j}\) is a matrix of cluster means, and \({Z}^{^{\prime}}\gamma\) denotes the individual- and country-level determinants and parameters from Eq. (2). Here, \({\beta }_{4}\) is the direct effect of SCTs on OME. If a mediating effect is present, the parameter estimates should be smaller in Eq. (3) than in Eq. (2). In other words, including the SCTs in the model reduces the magnitude of the effect of formal and informal institutions on OME.

4 Results

4.1 Logistic regression with correlated random effects

We begin the empirical analysis in Table 3, which reports the results from the CRE logistic regression. We first briefly discuss the results from model 4, which reports the pre-mediation effects of institutions on OME. Consistent with our second set of baseline hypotheses H2a and H2b, we observe that both pro-market institutions (\(\beta =0.214, p=0.000\)) and social legitimacy of entrepreneurship (\(\beta =0.063, p=0.000\)) are positively associated with OME. In model 5, we observe that opportunity recognition (\(\beta =0.137, p=0.000\)), entrepreneurial self-efficacy (\(\beta =0.341, p=0.000\)), and fear of failure (\(\beta =- 0.098, p=0.000\)) are all significant determinants of OME, consistent with our first set of baseline hypotheses H1a, H1b, and H1c.

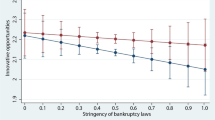

Next, we turn our attention to models 1–3, which report the direct effects of pro-market institutions and social legitimacy of entrepreneurship on each of the three SCTs. We observe that a stronger pro-market institutional environment is associated with a higher propensity for opportunity recognition (β = 0.201, p = 0.000) and higher rates of entrepreneurial self-efficacy (β = 0.026, p = 0.019), but that it has no discernible effect on fear of failure (β = 0.001, p = 0.901). We also observe that social legitimacy of entrepreneurship is associated with higher rates of opportunity recognition (β = 0.125, p = 0.000), entrepreneurial self-efficacy (β = 0.119, p = 0.000), and fear of failure (β = 0.041, p = 0.000). Moreover, we observe that pro-market institution is associated with higher rates of OME both before (β = 0.214, p = 0.000) and after (β = 0.160, p = 0.000) mediation. Similarly, social legitimacy of entrepreneurship is associated with higher rates of OME both before (β = 0.063, p = 0.000) and after (β = 0.022, p = 0.000) mediation.

The estimates for the SCTs in model 5 enable computation of the indirect effects of institutions on OME via each SCT using the relevant estimates from models 1–3. We observe an indirect effect of pro-market institutions via opportunity recognitionFootnote 7 (0.028), entrepreneurial self-efficacyFootnote 8 (0.007), and fear of failureFootnote 9 (– 0.000). Likewise, we observe an indirect effect of social legitimacy of entrepreneurship via opportunity recognitionFootnote 10 (0.017), entrepreneurial self-efficacyFootnote 11 (0.041), and fear of failureFootnote 12 (– 0.004). Moreover, we test whether or not SCTs mediate the relationship between institutions and entrepreneurship by comparing the coefficients on institutions between models 4 and 5 (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The results reveal that the three SCTs mediate 25% [(0.160–0.214)/0.214] of the institutional dimension’s effect on OME and 65% [(0.022–0.063)/0.063] of the informal institutional dimension’s effect on OME.Footnote 13

In summary, our findings provide support for the role of opportunity recognition and self-efficacy as mediating factors between (i) pro-market institutions (H3a and H3b) and (ii) social legitimacy of entrepreneurship (H4a and H4b) and OME. Additionally, our findings support the role of fear of failure as a mediating factor between social legitimacy of entrepreneurship (H4c), but not pro-market institutions (H3c), and OME. However, our results do not support H4c because we find that, contrary to our expectation, social legitimacy of entrepreneurship is positively associated with fear of failure.

4.2 SEM analysis

To corroborate our findings, we also investigate whether pro-market institutions and social legitimacy of entrepreneurship influence OME through the SCTs using structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM permits an examination of the extent to which SCTs mediate the relationship between institutions and OME. Specifically, we examine two structural links: (i) the effect of institutions (pro-market and social legitimacy of entrepreneurship) on opportunity entrepreneurship (Institutions → OME) and (ii) the effect of SCTs on OME (SCTs → OME). Importantly, SEM allows for us to separate the effect of institutions on OME into direct and indirect effects. SEM reports the direct effect as the effect on institutions on OME and allows for calculation of indirect effect as the product of the effect of institutions on SCTs and the effect of SCTs on OME (institutions → SCTs → OME). We summarize the SEM results in Fig. 2.

SEM model. Note: standardized coefficients reported. The model includes all basic controls from Table 3 and was estimated using Stata’s GSEM command. Estimation method: maximum likelihood; log likelihood: − 1,617,907; N = 735,244; number of countries = 86. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, and * p < 0.10

In the case of pro-market institutions, we observe both a positive direct effect (β = 0.160, p = 0.000) and an indirect effect (β = 0 0.035, p = 0.000) on OME. The indirect effect operates primarily through the channel of opportunity recognition (β = 0.028, p = 0.000), but it also operates through entrepreneurial self-efficacy (β = 0.007, p = 0.010). Specifically, we observe an indirect effect that runs from pro-market institutions to opportunity recognition (β = 0.201, p = 0.000), which, in turn, is associated with higher rates of OME (β = 0.137, p = 0.000). Similarly, we observe an indirect effect that runs from pro-market institutions to entrepreneurial self-efficacy (β = 0.021, p = 0.01), which, in turn, is associated with higher rates of OME (β = 0.341, p = 0.000). The combined total effect (direct + indirect) is a 0.195 increase in OME.Footnote 14

In the case of social legitimacy of entrepreneurship, we observe a much smaller direct effect of informal institutions on OME (β = 0.022, p = 0.000). However, we observe a much stronger indirect effect on OME, which operates through each of the three SCTs. Specifically, we observe indirect effects of social legitimacy of entrepreneurship on OME through the channels of opportunity recognition (β = 0.125, p = 0.000), entrepreneurial self-efficacy (β = 0.119, p = 0.000), and fear of failure (β = 0.041, p = 0.000). The total effect (direct + indirect) of social legitimization on OME is 0.051.Footnote 15 Table 4 summarizes the direct, indirect, and total effects of pro-market institutions and social legitimacy of entrepreneurship on OME.

4.3 KHB mediation analysis

We also examined our research question using KHB mediation analysis (Karlson et al., 2012). Table 5 summarizes the results. The primary benefit of the KHB approach is its ability to attribute the amount mediated to each of the three mediators. The results from the KHB method suggest that SCTs mediate approximately 15.6% of the effect of pro-market institutions on OME. However, the amount mediated is slightly larger than this estimate since fear of failure negatively mediates this relationship. This is consistent with the premise of “inconsistent” mediation (MacKinnon et al., 2000). Following this approach, we take the absolute value of all amounts mediated and find that the total amount mediated is actually 15.70%,Footnote 16 12.56% by opportunity recognition, 3.14% by entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and 0.10% by fear of failure.Footnote 17 However, the direct effect of pro-market institutions on OME remains statistically significant after mediation. Hence, we conclude that SCTs partially mediate the relationship between pro-market institutions and OME.

In addition, we observe that SCTs mediate 68.3% of the effect of social legitimacy of entrepreneurship on OME, or 78.83% Footnote 18 taking the absolute values: 21.33% from opportunity recognition, 52.23% from entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and 5.27% from fear of failure. Notably, the amount mediated is five times larger for social legitimacy of entrepreneurship than pro-market institutions (i.e., 78.83 vs. 15.70%). Although the direct effect of social legitimacy of entrepreneurship on OME is much smaller than the direct effect of pro-market institutions, the direct effect remains statistically significant after mediation. We thus conclude that SCTs partially mediate the relationship between social legitimacy of entrepreneurship and OME.

4.4 Additional results

4.4.1 Economic development

One possibility is that institutions may have differential effects on OME across levels of economic development. The literature exploring such heterogeneity is limited; thus, a natural extension of our research is to consider whether our findings are similar at varying levels of economic development. Institutions might exert a differential impact on entrepreneurship depending at the level of development due to, for instance, differences in infrastructure (Bennett, 2019), entrepreneurship contextualized as necessity vs. opportunity entrepreneurship (Nikolaev et al., 2018), and the effect that different stages of development (i.e., factor-driven, efficiency-driven, and innovation-driven) exert on entrepreneurship activity (Acs et al., 2008; Boudreaux, 2019). We thus rerun our analysis by separating our sample into high-income and low-income countries based on the median level of economic development. We report the results for the high-income sample in panel A and the low-income sample in panel B of Table 6.

We observe several takeaway points. To begin, the results from this exercise are similar to our full sample analysis, increasing the robustness of our findings. However, there are some interesting differences. For instance, social legitimacy of entrepreneurship exerts a larger impact on OME in high-income countries as compared to its effect in low-income countries. Moreover, we observe the exact opposite for pro-market institutions: the direct effect on OME is larger for low-income countries than high-income countries. Although social legitimacy of entrepreneurship exerts an impact on SCTs in both high-income and low-income samples, the effect sizes of pro-market institutions on SCTs are smaller in low-income countries as compared to high-income countries. We urge future research to consider these issues in more detail, as a more complex understanding of these relationships is beyond the scope of this study.

4.4.2 Necessity-motivated entrepreneurship

Another useful extension is to consider whether the relationships we have uncovered differ between opportunity-motivated and necessity-motivated entrepreneurship (NME). Entrepreneurship is synonymous with new venture creation and opportunity identification, but this conceptualization is more consistent with the notion of OME. NME, in contrast, is predominately concerned with lifestyle or subsistence, and it is not typically growth oriented. Moreover, studies report the cross-country distribution of entrepreneurship activity and reveal that countries with highest rates of entrepreneurship also have higher rates of NME (Acs et al., 2008; Boudreaux et al., 2019). We therefore consider how our results might differ when examining NME rather than OME. We report these results in panel A of Table 7.

We observe many similarities when comparing the results for NME and OME. Both pro-market institutions and social legitimacy of entrepreneurship exert positive effects on NME, and SCTs reveal a positive effect on NME for opportunity recognition and entrepreneurship self-efficacy and a negative effect for fear of failure. However, there are also some notable differences. For instance, the three SCTs mediate the relationship between pro-market institutions and NME by only 4%, which is significantly lower than the 25% mediated in the OME model. Social legitimacy of entrepreneurship is mediated by the three SCTs in similar magnitudes between OME (65%) and NME (66.7%). However, the direct effect of social legitimacy of entrepreneurship on NME becomes statistically insignificant after including the mediators, which suggests that the effect is completely mediated.

4.4.3 Country-level aggregation

One potential concern with our findings is that statistical significance might be overstated given the large sample size in our regression models. We follow recent editorial guidelines (Anderson et al., 2019) to mitigate against this concern, including reporting exact p-values and greater reliance on interpreting effect sizes (i.e., reporting standardized coefficients) rather than relying only on statistical significance. Nevertheless, for an additional robustness check, we report the results for our models using the measures aggregated to the country level. Hence, in these regression models, we no longer have hundreds of thousands of individuals. Instead, we have averages at the country-year level for a total of 428 observations. We report these results in panel B of Table 7.

The results are qualitatively similar to our main findings; however, the difference between the effects of pro-market institutions and social legitimacy of entrepreneurship on OME are more striking. Pro-market institutions exert a positive and direct effect on OME (β = 0.192, p = 0.000), with only a small amount mediated by the three SCTs (15%). In contrast, social legitimacy of entrepreneurship exerts strong direct effects on the three SCTs, with little influence on OME prior to mediation (β = 0.067, p = 0.109) and after mediation (β = – 0.031, p = 0.465). To summarize, we observe there is a direct effect of pro-market institutions on OME and an indirect effect of social legitimacy of entrepreneurship on OME through the three SCTs.

5 Discussion

5.1 Contributions

While there is a robust consensus among scholars that “institutions matter” for entrepreneurial action, our understanding of how institutions influence entrepreneurship remains limited. Recent work has moved toward a “configurational” view, emphasizing the effects of institutional-personal combinations on entrepreneurship (Boudreaux et al., 2019; Stenholm et al., 2013; Urbano & Alvarez, 2014; Wennberg et al., 2013). This work reveals the conditional nature of institutional effects, e.g., where one institutional dimension may strengthen or weaken (i.e., moderate) the direct effects of another dimension (Bennett & Nikolaev, 2021a; Li & Zahra, 2012). Across levels, Kim et al.(2016) write of “meso-level” social groups that can impinge on institution-actor processes. Similarly, a growing body of work also suggests that institutional context moderates the relationship between cognitive factors and entrepreneurship. For instance, Boudreaux et al. (2019) find a stronger link between individuals’ SCTs and entrepreneurship in countries with stronger pro-market institutions than in nations with weaker pro-market institutions.

Our study advances this work by examining the inter-relationship between institutions and SCTs in several novel ways. First, we account for both formal and informal institutional factors in our theoretical model (Bennett & Nikolaev, 2021a; Eesley et al., 2018; Li & Zahra, 2012), unpacking how formal and informal institutions influence entrepreneurial action through cognitive institutions as embodied within individuals. This view is also highly consistent with the NIE concept of shared mental models (Denzau & North, 1994; North, 1991), offering a greater integration of the institutional and cognitive views of entrepreneurship to facilitate a more holistic perspective (Foss et al., 2019; Grégoire et al., 2011).

To our knowledge, only Lim et al. (2010) consider the mediation of institutions through cognitive mechanisms. While their study breaks an important ground in this respect, it also raises questions about the theoretical relationship among the institutional dimensions and SCTs that our study engages. By including a mix of both developed and developing countries and a robust theoretical account, our model and results affirm the mediated nature of institutions and suggest generalizability across different contexts. Using several different econometric approaches, we found that between 15 and 25% of the effect of formal institutions on OME is mediated by SCTs. While this mediation proportion is relatively modest, it affirms that even formal institutions have profound implications for the perceptions of individuals. In contrast, we found evidence of larger mediation of informal institutions pertaining to social legitimacy of entrepreneurship. Since norms are socially constructed and often operationalized as an “aggregate” of individual values, it makes sense that these shared values positively influence individual SCTs conducive to entrepreneurship (Kibler et al., 2014; Wyrwich et al., 2016).

This is an important point to consider. Our results suggest informal institutions operate almost entirely through individual cognitive channels, and formal institutions have a much larger direct influence on OME. Whereas prior studies have documented important relationships between formal and informal institutions and entrepreneurship (Bennett & Nikolaev, 2021b; De Clercq et al., 2010; Stenholm et al., 2013), our findings suggest an important distinction: formal institutions exert a direct influence on entrepreneurship, and informal institutions exert more indirect effects on entrepreneurship (Bjornskov & Foss, 2016), through individual cognitive channels.

5.2 Practical implications

From a practical standpoint, our work goes beyond the question of “whether” institutions matter for entrepreneurship to “how” institutions matter, and we clarify that institutions partially influence entrepreneurial action through their relationship to individual SCTs. Our findings suggest that pro-market institutions increase individuals’ expectations of novel opportunities in the environment as well as increase their belief that they are personally able to exploit these opportunities. However, we also find that pro-market institutions have no effect on individual fear of failure. This suggests entrepreneurs may have very different mental models across institutional environments, yielding rich socio-cognitive heterogeneity in the entrepreneurial population across countries. While the literature highlights the importance of transaction mechanisms by which pro-market institutions encourage entrepreneurship (e.g., lower transaction costs and reduced uncertainty), our study suggests that they also act to encourage entrepreneurship, in part, by shaping individual SCTs. However, our findings suggest that transaction mechanisms appear to be the primary driver. Our main results suggest that the direct effect of pro-market institutional change on entrepreneurship is economically meaningful. More specifically, a standard deviation increase in pro-market institutions (i.e., 0.663, which is the approximate difference in the latest EFW scores between (a) the UK (8.15) and Singapore (8.81), or (b) Haiti (6.51) and Kyrgyz Republic (7.17)) is associated with a 0.16 standard deviation increase in OME (see model 5 of Table 4). Because the standard deviation of OME is 0.291, we can interpret this estimate as suggesting that one standard deviation increase in pro-market institutions is associated with a 4.7 percentage point increase (\(0.16\times 0.291=0.047\)) in the probability that an individual becomes an OME. While our findings reinforce the idea that policymakers can encourage more entrepreneurship through advancing pro-market reforms, they also bring to light a new argument to justify economic liberalization as entrepreneurship policy (Bennett & Nikolaev, 2019), namely, increasing individual control perceptions (Nikolaev & Bennett, 2016; Pitlik & Rode, 2016) to increase opportunity recognition and self-efficacy.

Our results regarding social legitimacy of entrepreneurship reinforce earlier findings on the influence of media and role models in shaping individual entrepreneurial cognition (Kibler et al., 2014). Some scholars have pointed to the link between media freedom and entrepreneurship (Sobel et al., 2010), and findings concerning the relationship between media attention and new venture activity are mixed (Hindle & Klyver, 2007; Urbano & Alvarez, 2014; von Bloh et al., 2020). Our work helps reconcile the mixed results of media attention in the literature and clarify that while the effects of such informal institutions on entrepreneurship are positive, they are primarily indirect through the shaping of individual SCTs. Importantly, we find that the social legitimacy of entrepreneurship positively influences OME by increasing opportunity recognition and self-efficacy; however, it negatively influences it by increasing individual fear of failure. The latter result is opposite of what we expected and somewhat inconsistent with the nuanced findings of Wyrwich et al. (2016), who examine the regional social legitimacy of entrepreneurship and fear of failure in Germany. Our findings, however, offer new insights into the tradeoffs that emerge with social legitimacy of entrepreneurship. While it is clear from our analysis that such informal institutions are, on the net, positive for entrepreneurial action, our work suggests there is room to further address their relationship with fear of failure. This suggests an opportunity for social ventures, third-sector organizations, or public policy to potentially mitigate these adverse effects.

Furthermore, we find notable differences in how institutions influence OME in high- and low-income countries. First, neither formal nor informal institutions affect individual fear of failure in the high-income countries in our sample; however, formal institutions are associated with less fear of failure and informal institutions with more fear of failure in our low-income country sample. Second, both formal and informal institutions are associated with greater individual self-efficacy in the high-income country sample; however, formal institutions are associated with less self-efficacy, and informal institutions had more self-efficacy in our low-income country sample. These important differences highlight that attempts to encourage more entrepreneurship by changing both formal and informal institutions in developing country contexts involve trade-offs. On the net, both pro-market institutions and social legitimacy of entrepreneurship are associated with increased OME in developing countries, but our findings suggest that more can be done to mitigate the offsetting individual cognitive effects of the institutional improvement. Our findings, therefore, contribute to the nascent body of literature suggestive that the processes by which institutions shape entrepreneurship may differ in developed and emerging economies (De Clercq et al., 2010; Tonoyan et al., 2010).

5.3 Limitations and future research guidance

One limitation of our work relates to the nature of our data. Like other studies utilizing the GEM survey data, our variables of interest (i.e., OME, SCTs) are coarse because individuals are not tracked over time. However, our work offers at least some theoretical scaffolding for longitudinal, processual research on how cognition mediates institutional influences throughout the entrepreneurial process. In particular, by positioning opportunity recognition as a third-person SCT and fear of failure and entrepreneurial self-efficacy as first-person SCTs, our work is suggestive of the influence of institutional dimensions on both recognition and assessment stages leading to entrepreneurial action (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006). Scholars may thus gain considerable insights by leveraging longitudinal sources of venture creation data that feature both founders’ cognitive traits and firm outcomes in varying institutional settings, particularly in the “fuzzy front end” of the entrepreneurial process (Bjørnskov et al., 2022).

Another potential concern is related to reverse causality. Although we theorize how institutions influence SCTs and entrepreneurship, it is also possible that entrepreneurs exert an influence on institutional development. As North, (1991) emphasizes, institutions also evolve due to the actions of entrepreneurs; in many ways, they are “bottom-up” phenomena. Henrekson & Sanandaji, (2011, p. 48) add, “institutions do not merely control entrepreneurs; entrepreneurs, in turn, control them through business activity, evasive methods, and political entrepreneurship.” Indeed, a growing body of literature acknowledges the potential bidirectionality between institutions and entrepreneurship (Bylund & McCaffrey, 2017; Garud et al., 2007; Pacheco et al., 2010). However, there is less reason to be concerned, given the nature of the GEM data and the infrequent nature of institutional change (Roland, 2004; Williamson, 2000), that the behavior of an individual in our sample will exert a major influence on the institutional environment over the course of our study (Boudreaux et al., 2019). As Aldrich (2012, p. 1240) notes, institutional entrepreneurship is a collective action process by which “many people who jointly, via cooperation and competition, create conditions transforming institutions.” Nonetheless, empirical examination of the potential bidirectionality between entrepreneurship and institutional change is a fruitful area for future research (Bennett & Araki, 2022), as it would help clarify the relative contribution of institutions as an entrepreneurial allocation mechanism vis-à-vis the role of entrepreneurs as disturbers of institutional equilibrium (Douhan & Henrekson, 2010).

Our multilevel mediation approach to institutions and entrepreneurship invites many promising directions for future research. Multilevel mediation studies have been rare until recently since methods are still evolving, as are tools for estimation in common statistical packages. We have demonstrated the viability and promise of such an approach here, showing several methods (each with its own tradeoffs) for exploring the pathways of institutional effects. Future work might exploit “onset” external changes that occur quite suddenly, alongside longitudinal data, to robustly evaluate the direct and indirect relationships between specific environmental changes and entrepreneurial action (Davidsson, 2015). This approach could leverage a well-identified “natural experiment” design to generate valuable insights.