Abstract

In response to a low fertility rate, a number of municipalities in South Korea have been providing family benefits in the form of childbirth grants and child allowances. Using panel data for 230 municipalities that spans the years 2001–2014, this paper examines the impacts of family benefits on the fertility rate in Korea. I use the fact that different municipalities began providing the family benefits at different times to estimate the impact of family benefits on fertility rates using a difference-in-differences approach. This study finds a positive effect of family benefits on total fertility rate. Moreover, it finds little evidence of an anticipatory response within municipalities that adopted the policy. Given that a 10 million Korean won increase in family benefits is associated with a 3.5% increase in the total fertility rate, an increase in family benefits of about 44 million Korean won per child would be required to raise the total fertility rate to a safe zone above 1.5 children per woman, where population declines are gradual and easily reversed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In response to a low fertility rate, governments in many industrialized countries have adopted policies to encourage couples to have children. According to the neoclassical economic theory of fertility (Becker 1981; Schultz 1990; Cigno 1991), pro-natal family policies aimed at offering family and childcare support are expected to have a positive effect on fertility by reducing the cost of having children (Gauthier 2001; Björklund 2006).

A number of studies have empirically investigated the impact of family policies on fertility. Many earlier studies were based on cross-national or time-series data (Ermisch 1988; Walker 1995; Gauthier and Hatzius 1997) and thus employed small sample sizes. Also, cross-national variations in family policies have limited usefulness for comparative purposes due to differences in cultures, preferences for number of children, and family income that may affect fertility rates. In addition, employment of time-series variation in family policies makes it difficult to estimate the causal effects of the policies when other changes are occurring simultaneously (Rønsen 2004; Björklund 2006). To shed light on whether government support for larger families encourages people to have more children, this paper investigates the impacts of family cash benefits for childbirth on the fertility rate in South Korea using panel data for 230 municipalities that spans the years 2001–2014.

Korea offers a particularly useful case study for inferring the effects of family policies on fertility. In that country, family policies have expanded substantially over the past decade in order to address a low birth rate. This study examines one such family policy that involves provision of childbirth grants and child allowances. Because the implementation of this policy has varied by time and municipality in Korea, this variation can be used to estimate the causal effect of the family policy on the fertility rate. In addition, this study investigates which socioeconomic groups are more affected by the family policy by estimating effects of family benefits on total fertility rate according to municipality characteristics such as baseline fertility rate, income level, and female labor force participation rate.

In this paper, one validity threat encountered when analyzing the effects of childbirth grants on fertility rate is that there may be unobservable municipality-specific factors that influence fertility rates. For example, municipalities with thriving economies may have low fertility rates because of the higher opportunity cost of having children. This phenomenon could bias estimates of the impact of childbirth grants downward if local governments are more likely to provide grants when their local economies are doing well. Alternatively, it is possible that municipalities with a stronger preference for reversing the population decline are more likely both to provide childbirth grants and to have high fertility rates for other reasons, biasing estimates upward. To address these issues, this paper accounts for the differences across municipalities that are time-invariant and that may be correlated with the independent variables by controlling for municipality fixed effects. Using fixed-effect models, this study finds that a 10 million Korean won increase in the total family support per child provided through childbirth grants and child allowances is expected to increase the total fertility rate by 3.5%. Given that the average regional income per capita during the sample period was about 25 million Korean won, the estimate implies that an increase in family benefits by about the average annual income per capita would increase the total fertility rate by 7%. Also, this study compares fertility rate patterns in municipalities that have and have not implemented the childbirth grant policy and shows that the policy increased the fertility rate by 2%.

Although the municipality fixed effects address all sources of time-invariant municipality unobservables, they cannot rule out the possibility that time-varying unmeasured factors bias estimates. For example, if municipalities provide childbirth grants based on current fertility rates, a comparison of fertility rates in municipalities having such a family policy and in municipalities not having the policy will not estimate the causal effect. In this case, low fertility rates may lead to provision of childbirth grants rather than the opposite. Furthermore, municipalities might adopt a family policy as a result of particularly strong economic conditions, and these conditions might directly impact fertility patterns.

Although it is not possible to completely rule out the possibility that time-varying unobservables bias estimates, several pieces of empirical evidence argue against this possibility. First, I show that there is no differential trend in fertility rates prior to family policy implementation and that there is no evidence that fertility rates either fall or rise in the year prior to implementation. This evidence is important because it rules out the possibility that municipalities adopt a family policy in response to declining fertility rates. Second, I find that the timing of the increase in fertility corresponds exactly with the timing that would be expected if the fertility increase were caused by the policy. Specifically, there is a small increase in the year of policy implementation followed by a larger and persistent increase in the future. While it is possible for time-varying unobservables to produce this same pattern there is little reason to expect that changing unobservables would be correlated with the timing of implementation in precisely this manner. Finally, this paper shows that the results are very robust when time-varying observable municipality characteristics are controlled for. In particular, one important threat to identification is the possibility that municipalities adopt a family policy based on current economic conditions, but this paper finds that estimates are virtually unchanged when time-varying unemployment rates or income levels are controlled for. Because it is likely that observable time-varying municipality characteristics are correlated with unobservable time-varying characteristics, the robustness of the results to these controls is reassuring.

Assuming that a 10 million Korean won increase in childbirth grants and child allowances is associated with a 3.5% increase in the total fertility rate, an increase in family benefits by about 44 million Korean won per child will be required to raise the total fertility rate above 1.5 children per woman, a safe zone where population declines are gradual and easily reversed.

Section 2 of this paper describes the family policy and fertility rate in Korea. Section 3 applies an economic framework and discusses how the economic incentives provided by the policy affect fertility. Section 4 presents the data used, and Section 5 presents the empirical strategy and results. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the study and discusses implications of the family policy.

2 Family policy and fertility rate in Korea

As is the case in many developed countries that have very low fertility, the government in Korea has provided family benefits to encourage having more children. Among a wide range of family benefit policies employed internationally to increase fertility rate, the most commonly used provide parental leave benefits and cash support. The former policy supports a balance between work and family life, whereas the latter is used as a means of providing financial support for having children. In Korea, maternity leave policy is enacted and implemented by the central government. According to this policy, Korean women have a legal right to 90 days of paid leave after giving birth to one child and 120 days of paid leave for multiple births. This policy compensates typical female workers with about 100% of their lost earnings. The paid maternity leave is provided nationwide, and the benefits have been fixed since 2001, when the initial policy reform occurred. Thus, there was no variation in the maternity leave policy across municipalities during the sample period of this study. In contrast to maternity leave benefits, however, family cash support in the form of childbirth grants (or baby bonuses) and child allowances has been provided to families in differing amounts across municipalities over time. This study focuses on the family cash benefit policy related to fertility and empirically evaluates the impact of this policy on the fertility rate in Korea.

In municipalities that have adopted the policy, the local government provides grants to families with a newborn child. This one-time grant is intended to support the costs of the mother’s delivery of a single child and subsequent infant care. In addition to the grant for a newborn infant, the local government provides child allowances, or subsidies, to support the costs of childrearing up to a certain age (a maximum of 6 years); each allowance is a fixed amount per child paid monthly to the mother in cash installments. Most of the municipalities differ in the grant amounts they offer according to the total number of children in the family. In general, such municipalities provide greater grant amounts to families with more children. For instance, in a specific municipality, (1) 500,000 Korean won of one-time grant and 600,000 Korean won of total child allowance are granted to families for their first and second children; (2) 3,000,000 Korean won of one-time grant and 1,800,000 Korean won of total child allowance for their third child; (3) 3,000,000 Korean won of one-time grant and 2,100,000 Korean won of total child allowance for their fourth child, and so on.

The family benefits provided by the policy considered in this study consist solely of cash support for families with newborn or young children. Depending on the specific municipality and time period involved, the total amount of any cash support issued to families varies greatly. For example, the most generous local government provides monthly cash allowances totaling 51 million won for children up to age 6 in addition to a one-time cash grant of 25 million won at birth, whereas some local governments provide no cash support at all. For the purposes of this study, all childbirth grants and child allowances are referred to as the family policy below.

The family policy in Korea was markedly extended during the last decade. However, the fertility rate did not substantially increase during the same period. Figure 1 shows how the distribution of fertility rates and family benefits differs by municipality over time. For comparison, fertility rates and family benefits by municipality in 2005 and 2013 are illustrated in parallel. It is noteworthy that relatively few municipalities provided family benefits in 2005, whereas more than half of the 230 municipalities provided such support in 2013. However, the overall fertility rate was lower in 2013 than in 2005. A significant portion of this decreasing trend in fertility can be explained by a societal tendency to postpone marriage and a decrease in the marriage rate over the last decade in Korea (Lee 2009). The marriage rate has been gradually declining and reached 5.9 per 1000 population in 2015, the lowest rate since recordkeeping began in 1970. In addition, ages at first marriage have been increasing, and in 2015, the average ages at first marriage were 32.6 and 30 years for men and women, respectively. Moreover, the low fertility rate in Korea can be attributed to other societal changes: the high cost of raising children due to high housing and education costs, uncertainty about the economy and employment, difficulties in balancing work and family obligations, and attenuation of traditional values (Lee and Choi 2015).

The low fertility rate is a national concern in Korea, but the fertility problem is more concentrated in certain socio-economic groups. Table 1 shows the distribution of births by women’s socio-economic characteristics. Columns (2)–(6) respectively show the percentage of families with no child, one child, two children, three children, and four children or more. The overall distribution presented in the first row shows that 27% of families have either no or a single child, 57% have two children, and 16% have three or more children. However, the distribution differs when the population is categorized by family income, maternal education, and maternal labor force participation. The table reveals that high-income families tend to have more children than low-income families; the higher the mother’s education level is, the fewer children the family tends to have; and families have fewer children when the mother is employed.

3 Theoretical framework

The neoclassical model of consumer choice can be applied to explain parents’ demand for children. Assuming that there is no obstacle to the ability of parents to choose their family size, parents choose their number of children to maximize their utility (Becker 1981; Cigno 1991; Hotz et al. 1997; Enache 2013). In this model, parents’ utility can be denoted as:

where C is number of children and X is bundle of goods. Equation 1 states that number of children and all other goods are two broad sources of utility for parents. Parents can have very different preferences about the two competing sources of utility. Some parents may want many children, while others may prefer to have one or none at all. Parents maximize their utility under the budget constraint:

where Y is income, P C is per unit price of children, and P X is per unit price of the composite commodity. Specifically, P C is the cost of the parental time and market goods used to rear a child and can be written as:

where W M andW F are the wage rates for the mother and father, respectively, and T M and T F are the parental time of the mother and father, respectively. Z is market goods used in child rearing, and P Z is the associated price. As shown in Eq. 3, the cost of having a child, P C , consists of two components: the foregone earnings for the parent who gives up paid work to look after the child, which is the opportunity cost to have a child, and the direct costs of rearing the child such as spending on food, clothes, and housing.

Parents’ utility is maximized when the two goods are chosen such that the ratio of marginal utility to price is the same for each good. Thus, the utility-maximizing number of children and composite commodity, C * and X *, should be chosen such that:

Finally, from Eqs. 1–4, the demand for children can be written as:

This demand function of children provides a clear understanding of the relationship between the family policy and the fertility rate. Family-friendly policies aimed at reducing the cost of children or at increasing income are expected to have a positive effect on the demand for children. For instance, a paid maternity leave will increase demand for children because it lowers the opportunity cost to have a child (Adsera 2004). On the other hand, family benefits such as childbirth grants and child allowances are expected to increase fertility by increasing family income through cash transfer. Because in Korea paid maternity leave policy has been enacted by the central government and universally implemented across municipalities since 2001, no variation in this policy’s implementation can be exploited during the sample period in this study. Therefore, this study focuses on the family policy that lowers the direct costs of having a child. Specifically, this study considers the total monetary amounts of childbirth grants and child allowances to investigate the effect of this family policy on fertility.

4 Data

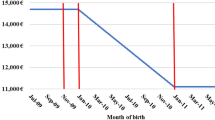

The data employed for the study contains information on childbirth grants, child allowances, and fertility rates for 230 Korean municipalities that spans the years 2001 through 2014. Figures 2 and 3 respectively illustrate the trends in the total fertility rate and proportions of municipalities offering childbirth grants and child allowances during the sample period. At the beginning of the sample period, the total fertility rate declines from 1.6 to 1.2 and stabilizes at this low level; from 2005 to 2012, it slightly increases to 1.4; and then from 2012 to 2014, it decreases by about 0.1–1.3. Overall, for the last decade, the total fertility rate in Korea has been stagnant at a low level lying mostly between 1.2 and 1.4. It is commonly accepted that in countries whose total fertility rate is below 1.5 children per woman, the population declines rapidly, and this trend is rarely reversed; thus, a total fertility rate of 1.5 children per woman and above is called the “safe zone” (McDonald 2006). In Korea, the most recently reported total fertility rate is about 1.3, which is below the safe zone.

As the fertility rate has remained low, a number of Korean municipalities have adopted a family policy. Figure 3 shows the trend in the percentage of municipalities offering family benefits. As shown in the figure, before 2004, no municipalities were providing family benefits, but thereafter the percentage of municipalities offering this support increased steadily. Since 2011, almost 90% percent of the municipalities have provided the family benefits.

Of the several commonly used fertility measures, this study employs the age-specific fertility rate (ASFR) and total fertility rate (TFR). The ASFR is the number of births occurring during a given year per 1000 women of reproductive age (i.e., of ages 15–49) classified in 5-year age groups. The TFR is the average number of children that would be born alive to a woman during her lifetime if she were to give birth during her childbearing years according to the ASFR schedule. Because the likelihood of having a child varies with age, the ASFRs are important measures in fertility research. The TFR is the most widely used fertility measure and is computed by summing the single-year ASFRs. Because the ASFRs are defined for seven 5-year age groups, the TFR used in this study is computed by summing all seven ASFRs and multiplying the total by 5, as there are 5 years in each age group. Figure 4 shows the ASFRs in 2000, 2007, and 2014. The age pattern of fertility seen in these ASFRs suggests that women are bearing children at younger ages in 2000 and 2007, with fertility peaking at ages 25–29, compared to 2014. However, the overall fertility rate in 2000 is higher than that in 2007. Although 2014 exhibits a similar overall fertility rate to 2007, a later age pattern of fertility is apparent in 2014, with childbearing concentrated at ages 30–34.

In this study of the family policy, the key independent variable is family benefits, which consists of childbirth grants and child allowances, and the outcome variables are the TFR and ASFR. Data for these variables is drawn from Municipality Population Policy Case Studies that span the years 2001 through 2014. For the control variables, regional gross domestic product, regional income, and male and female unemployment rates, data from the Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS) is used.

This study uses an intensive margin of data spanning 2007–2014 for fixed-effect analyses because there is little variation in family benefits until 2007. However, this study also uses an extensive margin of data spanning 2001–2014 in order to compare fertility rate patterns in municipalities that have and have not implemented the childbirth grant policy. The extensive margin analyses use a dummy variable for the policy as a variable of interest.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the sample for 2007–2014. Because not all Korean municipalities have adopted the family policy, support amounts are computed as averages for the municipalities providing support.

5 Empirical strategy and results

5.1 Effect of the family policy on fertility

Figure 5 depicts the trends in total fertility rate for the treatment and control groups using data for the extended period of 2001–2014. The treatment group is defined as municipalities that adopt the policy during the sample period, while the control group consists of municipalities that do not adopt the policy during the period. As shown in this figure, the treatment and control groups exhibit similar trends before 2004, but the trends begin to differ starting in 2004. This difference in fertility rate growth reflects the fact that the percentage of municipalities adopting the policy began to substantially increase in 2004, as shown in Fig. 3. However, the difference is just suggestive because it does not account for the magnitude of the grant. Moreover, the seemingly positive relationship between the family benefits and total fertility rate shown in Fig. 5 should not necessarily be interpreted as a causal effect of support on fertility rate. The main validity threats encountered when analyzing the effects of support on fertility rate can be summarized in two ways. First, unobserved factors that influence fertility may exist. For example, different environments that are conducive to having children may exist across municipalities, but such municipality-specific characteristics are difficult to observe and are therefore likely to be omitted in the model. Second, we cannot dismiss the possibility of simultaneity problems (Castles 2003). For example, the amount of family support issued could be the result of a low fertility rate in some municipalities, which would constitute a reverse causality. Both the potentially omitted variables and the potential simultaneity would likely cause endogeneity problems and lead to a biased estimator.

To analyze effects of the family policy on the total fertility rate, this study uses the following empirical model:

The dependent variable is the logarithm of the total fertility rate (i.e., children per woman) in municipality i in year t + 1, lnf i,t+1. It is assumed that there is a 1-year lag between changes in the independent variables and fertility rate. The vector of the control variables, \(X_{it}^{\prime}\), includes municipality time-varying characteristics such as regional income and male and female unemployment rates.

To allow for the differences across municipalities, which are time-invariant and may be correlated with the independent variables, the analysis controls for municipality fixed effects, \(\mathop {\sum }\nolimits_{k = 1}^{230} {\beta _k}muni{c_{ki}}\). The municipality fixed effects are useful for capturing the unobserved municipality-specific variations in a single municipality-specific intercept. Moreover, to control for the trend in total fertility rates that is common to all municipalities, a full set of time dummies, \(\mathop {\sum }\nolimits_{j = 2001}^{2014} {\gamma _j}yea{r_{jt}}\), is included in the model. The time fixed effects address possible external shocks common to all municipalities that would have a certain impact on fertility, such as the financial crisis of 2008.

The results are presented in Table 3A. The first two columns show the effect of family benefit amount on the logarithm of the total fertility rate, ln f i,t + 1. The variable of interest, support it , measures total grant amount per child. As mentioned in section 2, childbirth grants and child allowances differ by birth order in most municipalities that provide benefits. Thus, support it is created by weighting the total sum of birth order-specific one-time grants and child allowances measured in millions of Korean won with the frequency of birth order-specific birth rates at t−1. Thus, this variable can be considered as the total grant amount (i.e., one-time grant plus child allowances) per child over the child’s lifetime. The coefficients show that a 1 million Korean won increase in support is expected to increase the total fertility rate by 0.35%. Considering the fact that family income is one of the most important determinants of the demand for children, this study uses the ratio of family benefits to Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) (hereafter referred to as the support ratio) as another basic specification. The results are given in columns (3) and (4). The coefficient for the support ratio in column (4) shows that an increase in support equal to the GRDP in a municipality will increase the total fertility rate by over 7%. These results are consistent with the view that the decision to have a child is affected by the associated direct cost, which can be attenuated by family benefits.

The family policy effect would be expected to occur the year the policy is passed if families had advance information on the support for which they would be eligible at the time of their having a child. In fact, in Korea, a family policy tends to be publicly announced 6 months to 1 year before the policy’s implementation. For a couple trying to have a baby, on average it takes 6–9 months for the woman to become pregnant and then 9 months to have the baby. Thus, for typical couples, the policy will have effects on fertility 15–18 months after the policy announcement. If people have one year warning of the policy, then we would see an effect of the policy in the year the policy is passed. To check this, the logarithm of the fertility rate in year t, lnf i,t , is also used as a dependent variable as shown in specifications (5) and (6) of Table 3A. The estimated effects of the support ratio are 10% lower than the estimates in columns (3) and (4) and are not statistically significant. Similar specifications using a lag of the total fertility rate as a dependent variable show much smaller and statistically insignificant estimates as presented in columns (7) and (8). The latter results suggest that the positive effects of the family benefits are not resulting from the pre-trend.

Additionally, to examine the effect of the family policy on fertility, this study uses an extended sample period to compare the policy’s impacts across treatment and control groups. As defined above, in this specification, the treatment group consists of municipalities that adopt the policy during the sample period, while the control group includes municipalities that do not adopt the policy during the period. Table 3B reports the corresponding point estimates of the family policy effects on the total fertility rate in the treatment group as compared to the control group. The estimates of δ in Eq. 1 suggest that the policy increased the total fertility rate by 1.8%.

The key assumption behind these estimates is strong. The DID approach assumes that without policy implementation, the treatment municipality trend is what we should expect to see in the control group. The comparison of fertility patterns across the treatment and control groups shown in Fig. 5 provides evidence for the common trends assumption. The fact that the total fertility rates in the two groups move almost in parallel between 2001 and 2004, with the fertility rate declining at the beginning of the period and stabilizing thereafter, is consistent with the common trends hypothesis for an untreated period. This result shows that the DID analysis is a valid method for the purposes of this study.

5.2 Potential sources of bias

Section 5.1 finds a positive effect of the family policy on the total fertility rate. The models reduce the possible omitted variable bias by controlling for time-invariant municipality characteristics and time fixed effects. However, municipality fixed effects cannot account for all the changes in fertility rate, and this issue must be addressed to estimate the causal effect of the policy on fertility. Therefore, this section discusses potential sources of bias that are not fully accounted for by controlling for municipality-specific effects and attempts to address the issues.

First, if there was a declining pattern of fertility in municipalities that were about to adopt the family policy, this fact would lead to a bias to the opposite direction and underestimation of the policy’s effect. In addition, if municipalities experienced a significant drop in the fertility rate prior to policy adoption because of a macroeconomic shock, the causal relationship between the policy and fertility rate would be misleading. The estimated effect of the policy simply reflects the pre-trend of the fertility rate in the municipalities. Moreover, if low fertility rates lead to the policy rather than the opposite, the estimated effects of the policy on fertility rate would be biased because of this reverse causality. To address these issues related to a pre-trend, this study explores the pre-trend fertility rate. Furthermore, to identify meaningful policy implications, it is worthwhile to examine how quickly fertility rate grows in response to family policy adoption and how long the impacts persist after policy support begins.

Table 4 provides estimates of the Table 3A and 3B models augmented with leads and lags of the policy. In addition, Fig. 6 depicts the coefficients on the policy leads and lags from the preferred specification, which is shown in column (2) of Table 4. Specifically, indicator variables are added for 1–3 years and 4 or more years before policy adoption, the starting year through 3 years after policy adoption, and 4 years or more after policy adoption. The coefficients on the policy leads are slightly below zero, showing little evidence of an anticipatory response within municipalities about to adopt the policy. These results indicate that it is unlikely that municipalities are adopting the policy because of a low fertility rate.

Effects on total fertility rate for years before the policy, the year of the policy, and years after the policy (2001–2014). Note. The y-axis is the estimated coefficient on the policy leads and lags from the preferred specification, which is shown in column (2) of Table 3A and 3B. Vertical bands represent ±1.96 times the standard error of each point estimate

The results in Table 4 and Fig. 6 also show the timing of when the policy takes effect, which could be associated with how the policy was publicly announced. In the starting year of the policy, the coefficient is close to zero, but the total fertility rate then increases substantially until 2 years after policy adoption, at which point it becomes relatively stable.

As another potential source of the selection problem, one might consider couples’ potential decision to relocate because couples who are planning to have a child could move to municipalities where family benefits are higher. If this is the case, the estimates of this study are an upper bound because such relocation would inflate the fertility rate in areas with more generous policies. However, the effect would be small because in most municipalities, childbirth grants are provided only to individuals who have been municipality residents for at least 6 months. Nonetheless, this study tests the relocation concern by examining how the family policy affects the number of women of child-bearing age in each municipality. Table 5 presents the estimated effect of the family benefits on the number of reproductive-age women (i.e., ages 20–45). For all specifications, the coefficients show negative effects, meaning that the family benefits do not affect parents’ relocation decision.

5.3 Heterogeneous effects of the policy

If differentials in the family policy’s effects exist across the Korean population, it is necessary to investigate the heterogeneous effects and identify the subpopulations who are most responsive to the policy. The findings of such an investigation will help Korean policymakers allocate family support subsidies more efficiently and effectively.

Because the likelihood of having a child varies by age, and because economic conditions also vary by age, the effects of family benefits on women’s fertility behavior may differ by age as well. Thus, this study separately evaluates the effects of support on age-specific fertility rates. Table 6A reports the effects of the support ratio on age-specific fertility rates for women in their reproductive years. Of seven age-specific fertility rates, the support appears to have positive effects on age 30–34 and 40–44 fertility rates. Large standard errors, particularly for the highest age groups, indicate that most parts of the estimates are not statistically distinguishable across age groups. Nevertheless, compared with the baseline regression in Table 3A, the point estimates for the age 30–34 and 40–44 fertility rates are much larger. The estimates for the age 30–34 and 40–44 fertility rates are 0.14 and 0.39, respectively; these values are two and five times higher than the estimates from the baseline regression. Table 6B shows the results from the extensive margin used to analyze the effects of the policy on age-specific fertility rates. The estimates show that the policy positively affects most of the age-specific fertility rates--specifically those for the 25–29 through 40–44 age groups—while the effects are largest for the age 35–39 and 40–44 fertility rates.

The effects of family benefits on the fertility rate may also differ across the population. Based on theory, differential effects of the policy may exist in different subgroups of the population. First, generous support may greatly affect low-income families but matter little to wealthy parents. This is likely because higher individual earnings increase the opportunity cost of not working in the event of childbirth and childcare (Enache 2013). Also, the family benefits correspond to a much larger percentage of income for poorer individuals. Second, higher cash benefits are expected to have positive effects on demand for children among unemployed parents while the policy may not significantly affect demand for children among well-paid executives. A third distinction involves the marginal effect of cash benefits on the fertility rate. If we assume the existence of economies of scale in a family, as in Gauthier and Hatzius (1997), the costs of higher birth-order children are less than those of lower birth-order children. In this case, the effect of the policy would be expected to be larger for municipalities with a higher baseline fertility rate. To account for this possible municipality heterogeneity, this study investigates the effects of family benefits on total fertility rates according to municipality time-varying characteristics: the baseline fertility rate, average regional income level, and female labor force participation rate (LFPR).

The baseline fertility rate is defined as the fertility rate in the 1st year of the sample period. The baseline fertility rate used in estimating the effect of the support ratio is the average fertility rate in 2007, 1.334, and that used for the extensive margin is the average fertility rate in 2000, 1.53. The estimated effects of the support ratio for sub-population groups according to baseline fertility rate in municipalities are presented in columns (1) and (2) of Table 7A. The coefficient for the variable of interest, the support ratio, is larger for municipalities with a higher baseline fertility rate than for municipalities with a lower baseline fertility rate, but neither estimate is statistically significant.

The models in columns (3) and (4) of Table 7A present the estimated results for sub-population groups according to average income level in municipalities. The results show a positive effect of the support ratio on the total fertility rate for municipalities with a lower income level, while there is no statistically significant effect for municipalities with a higher income level. For the former subgroup, the increase in support by the GRDP is expected to increase the total fertility rate by about 12%, which is larger than the estimated effect in the baseline regression in Table 3A.

Considering the fact that opportunity costs of having a child are greater if a woman is working rather than not working, family cash benefits compensate the foregone earnings for working women when other family policies remain constant. In this context, the cash benefits are more effective for working women than for their counterparts not participating in the labor market, and thus the aggregate effects are expected to be larger in municipalities with higher female LFPR. The estimates for the two subsamples, municipalities with higher female LFPR and those with lower female LFPR, are given in columns (5) and (6) of Table 7A. The estimated coefficient for the support ratio is positive and statistically significant for the municipalities with higher female LFPR. This result is consistent with theory predictions.

The possible heterogeneity in the effects of family benefits is also addressed by using an extensive margin, and the results are reported in Table 7B. The sample is divided into subsamples using the same scheme as is described above. However, the results of the extensive margin analyses are slightly different from those in Table 7A. These differences merit some examination. First, with respect to the extensive margin, the fertility rate estimates are positive and statistically significant for all six subsamples, while with respect to the intensive margin, the estimates for some subsamples are not statistically significant. These differences may be attributable to the smaller subsample sizes in the intensive margin analyses. Second, for the subsamples analyzed by baseline fertility rate, the effects using the extensive margin are positive for both subsamples, but the magnitude of effects is greater for the municipalities with a lower baseline fertility rate. These results can be explained by the diminishing marginal returns of the policy. Third, with respect to the extensive margin, both subsamples show positive policy effects by income level, with a slightly stronger positive effect for low-income municipalities. Finally, the effect using the extensive margin is positive in both subsamples and is higher in municipalities with higher female LFPR, similar to the estimates in Table 7A.

The results identifying heterogeneous policy effects across the population are expected to be useful for Korean policymakers, who can target certain subpopulations for greater support in order to maximize the family policy’s effectiveness. From another perspective, they could also make the policy more cost-effective by providing less support to subpopulations who tend to have children regardless of the availability of cash benefits.

6 Discussion and conclusion

Because of its extremely low fertility rate along with its increasing life expectancy, Korea is currently challenged by an aging population as one of its largest societal concerns. The country’s proportion of elderly people (age 65 and above) is predicted to increase from 10% in 2009 to 20% in 2026, 30% in 2037, and 40% in 2060 (Lim and Lee 2014). To address the problems posed by an aging population, such as a shrinking labor force and increased government spending on social security and healthcare, policy interventions are urgently needed to increase fertility in Korea.

In this study, family benefits in the form of childbirth grants and child allowances are shown to be effective to some degree in increasing the fertility rate. In the sample of 230 Korean municipalities, family benefits in the form of cash benefits proved to have a statistically significant positive effect on fertility. However, the question remains as to whether the policy has true economic significance. Based on the baseline regressions of this study, the estimates indicate that a 10 million Korean won increase in support per child is associated with a 3.5% increase in the total fertility rate. Therefore, it would cost about 44 million Korean won per child to raise the total fertility rate to the “safe zone” above 1.5 children per woman. Given that the average regional income per capita was about 25 million Korean won during the sample period and that the average monthly two-or-more-member household income in Korea was about 4.3 million Korean won in 2016, I conclude that in terms of cost-effectiveness, the policy may not be a satisfactory social instrument for boosting fertility.

These results are consistent with previous findings for family policies in other countries. In general, earlier empirical studies on the effect of family policies on fertility have found a positive but small impact on fertility (see the 2013 review by Gauthier for more details). However, there is an exception that showed a strong impact of financial benefits on fertility. A 2005 study investigated the relationship between tax incentives and fertility in Quebec, Canada, and found that a 1000 Canadian dollar increase in benefits increased the probability of having a child by 16% (Milligan 2005). As a reason for the limited impact of family benefits found in my and other studies, it has been pointed out that the family benefits compensate for only a small fraction of the cost of having a child (e.g., see Thévenon and Gauthier 2011). In contrast to policies intended to reduce the direct cost of children, family policies that support a work-family balance and reduce the opportunity cost, such as generous maternity leave, take-up of paternity leave, provision of childcare services, and flexible working hours, have more decisive effects on fertility (Del Boca et al. 2009; Duvander et al. 2010; Kalwij 2010; Rindfuss et al. 2010; Thévenon 2011). For example, Nordic countries exhibit remarkably high female labor supply and relatively high fertility rates because the family-friendly policies of those countries weaken the negative trade-off between women’s labor supply and fertility (Gupta et al. 2008; Kalb and Thoresen 2010; Hanappi and Müllbacher 2016; Joona 2017). Thus, it is useful to consider how the public funding currently available could be best applied to increase the fertility rate to a more sustainable level in the near future.

Although the economic significance of family benefits in the form of childbirth grants and child allowances is open to debate, it is noteworthy that the policy does affect family’s childbearing decisions despite the rigidity in individual preference for number of children combined with the recent strong negative trends in fertility and marriage rates in Korea. This finding may indicate that a symbolic effect exists in which the policy makes parents feel that they are supported by the government in their decision to have a child. If this is the case, supportive family policies should be accompanied by a concerted government effort to create a more family-friendly social environment in order to resolve the low fertility problem.

Finally, the findings of this study highlight the importance of Korean public support for the costs of having children and indicate that properly targeted policies can affect individual childbearing choices. The results of this study also indicate that the family policy would be more effective if it targeted particular subgroups of municipalities—those with a low baseline fertility rate, low income level, and high female LFPR. Using this targeting strategy, policy support amounts could be adjusted to have the maximum impact on a given subpopulation.

References

Adsera, A. (2004). Changing fertility rates in developed countries. The impact of labor market institutions. Journal of Population Economics, 17(1), 17–43.

Becker, G. S. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Björklund, A. (2006). Does family policy affect fertility? lessons from Sweden. Journal of Population Economics, 19(1), 3–24.

Castles, F. G. (2003). The world turned upside down: below replacement fertility, changing preferences and family-friendly public policy in 21 OECD countries. Journal of European social policy, 13(3), 209–227.

Cigno, A. (1991). The economics of the family. New York, NY; Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Del Boca, D., Pasqua, S., Pronzato, C. (2009). Market work and motherhood decisions in contexts. Oxford Economic Papers, 61(1), 147 171.

Duvander, A. Z., Lappegård, T., Andersson, G. (2010). Family policy and fertility: Fathers’ and mothers’ use of parental leave and continued childbearing in Norway and Sweden. Journal of European Social Policy, 20(1), 45–57.

Enache, C. (2013). Family and childcare support public expenditures and short-term fertility dynamics. Panoeconomicus, 60(3), 347–364.

Ermisch, J. (1988). Econometric analysis of birth rate dynamics in Britain. The Journal of Human Resources, 23(4), 563–576.

Gauthier, A. H. (2013). Family policy and fertility: do policies make a difference? In A. Buchanan & A. Rotkirch (Eds), Fertility rates and population decline (pp. 269–287). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gauthier, A. H. (2001). The impact of public policies on families and demographic behaviour. Bad Herrenalb: The Second Demographic Transition in Europe 2328.

Gauthier, A. H., & Hatzius, J. (1997). Family benefits and fertility: an econometric analysis. Population Studies, 51(3), 295–306.

Gupta, N. D., Smith, N., Verner, M. (2008). The impact of Nordic countries’ family friendly policies on employment, wages, and children. Review of Economics of the Household, 6(1), 65–89.

Hanappi, T. P., & Müllbacher, S. (2016). Tax incentives and family labor supply in Austria. Review of Economics of the Household, 14(4), 961–987.

Hotz, V. J., Klerman, J. A., Willis, R. J. (1997). The economics of fertility in developed countries. Handbook of population and family economics, 1, 275–347.

Joona, P. A. (2017). Are mothers of young children more likely to be self-employed? The case of Sweden. Review of Economics of the Household, 15(1), 307–333.

Kalb, G., & Thoresen, T. O. (2010). A comparison of family policy designs of Australia and Norway using microsimulation models. Review of Economics of the Household, 8(2), 255–287.

Kalwij, A. (2010). The impact of family policy expenditure on fertility in western Europe. Demography, 47(2), 503–519.

KOSIS. (2016). Korean Statistical Information Service database. http://www.kosis.kr.

Lee, S. S. (2009). Low fertility and policy responses in Korea. The Japanese Journal of Population, 7(1), 57–70.

Lee, S., & Choi, H. (2015). Lowest-low fertility and policy responses in South Korea. In R. R. Rindfuss & M. K. Choe (Eds.), Low and Lower Fertility (pp. 107–123). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Lim, J., & Lee, J. H. (2014). Direction and support level of the fertility welfare policy in South Korea. Journal of Population Ageing, 7(2), 115–141.

McDonald, P. (2006). Low fertility and the state: The efficacy of policy. Population and Development Review, 32(3), 485–510.

Milligan, K. (2005). Subsidizing the stork: New evidence on tax incentives and fertility. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87(3), 539–555.

Rindfuss, R. R., Guilkey, D. K., Morgan, S. P., Kravdal, Ø. (2010). Child-care availability and fertility in Norway. Population and Development Review, 36(4), 725–748.

Rønsen, M. (2004). Fertility and family policy in Norway—A reflection on trends and possible connections. Demographic Research, 10, 265–286.

Schultz, T. P. (1990). Testing the neoclassical model of family labor supply and fertility. Journal of Human Resources, 25(4), 599–634.

Thévenon, O. (2011). Does Fertility Respond to Work and Family-life Reconciliation Policies in France? Fertility and Public Policy. In N. Takayama & M. Werding (Eds.), How to Reverse the Trend of Declining Birth Rates (pp. 219–259). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Thévenon, O., & Gauthier, A. H. (2011). Family policies in developed countries: A ‘fertility-booster’with side-effects. Community, Work & Family, 14(2), 197–216.

Walker, J. R. (1995). The effect of public policies on recent Swedish fertility behavior. Journal of Population Economics, 8(3), 223–251.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Son, Y.J. Do childbirth grants increase the fertility rate? Policy impacts in South Korea. Rev Econ Household 16, 713–735 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-017-9383-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-017-9383-z