Abstract

From the mid-1960s to around 1980, Sweden extended its family policies that provide financial and in-kind support to families with children very quickly. The benefits were closely tied to previous work experience. Thus, women born in the 1950s faced markedly different incentives when making fertility choices compared to women born only 15–20 years earlier. This paper examines the evolution of completed fertility patterns for Swedish women born in 1925–1958 and makes comparisons to women in neighbouring countries where the policies were not extended as much as in Sweden. The results suggest that the extension of the policy raised the level of fertility, shortened the spacing of births, and induced fluctuations in the period fertility rates, but it did not change the negative relationship between women’s educational level and completed fertility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Can public policies boost fertility in a modern society by providing financial and in-kind support for families with children? This is a classical question in academic and policy circles. It is also a burning issue in European discussions, as fertility rates fall in most countries, while life expectancy rises and contributes to larger aging populations.

It is hardly surprising that the scientific community cannot provide clear-cut evidence on the impact that various family policies—I use the concept family policy for measures that provide financial and in-kind support for families with children—have on overall fertility rates. Typical micro-data sets are of limited use because all women (or families) face the same incentives that result from family policies. Time-series variation in family policies within a country is also difficult to use because policies change only slowly over time, and other changes also occur. The remaining option is to use cross-national variation in family policy and fertility, but there are pitfalls in such analyses as well.

My thesis in this paper is that my country, Sweden, is a particularly useful case study to infer effects of family policies on fertility. I have three arguments that favour this claim. First, family policies were expanded quickly in Sweden. From the early 1960s to around 1980 (i.e. in less than 20 years), the generosity increased markedly for paid maternity leave, subsidised child care, paid leave to take care of sick children, and universal child allowances. In retrospect, the speed with which these policies were extended was striking.

Second, as already alluded to, several policies had a specific design, namely, that they facilitated labour force participation for mothers. Thus, the policies could potentially affect the structure of fertility, i.e. timing, spacing, and socio-economic differentials, as well as the overall level of fertility.

Third, pronatalistic arguments did not motivate the policies. In particular, they were not the outcome of a low-fertility period. This fact does not naturally guarantee that the expansion of family policy can be considered exogenous with respect to fertility. However, it would have been more problematic to interpret the Swedish experience if, e.g. a sharp drop in fertility rates had preceded the introduction of the new policies.

Rapid family policy expansion from the early 1960s to around 1980 implies that those generations of women who planned their childbearing before the expansion, i.e. women born during the 1920s and most of the 1930s, faced markedly different incentives than women born from the 1950s onwards. Therefore, I study changes in fertility patterns between these generations of women in Sweden. Because fertility patterns could change for reasons other than policy changes, I compared the evolution of fertility patterns in Sweden with the evolution in other countries. I primarily compared Sweden with its Nordic neighbours (Denmark, Finland, and Norway). In many respects, these countries pursued a similar family policy, but they did not go as far as Sweden. I also compared the evolution in Sweden with continental European countries (plus the UK) that pursued quite different family policies compared to Sweden.

Section 2 of this paper describes family policy implementation and employment legislation from a comparative perspective. Section 3 applies an economic framework and discusses how the economic incentives formed by family policy could affect the level and structure of fertility. Section 4 presents the empirical strategy. Results are organised by the impact of family policy on (1) overall level of fertility, (2) fertility levels by educational groups, (3) timing of childbearing, (4) spacing of childbearing, and (5) fluctuations in total fertility rates for the period. Section 6 summarises and discusses the main results.

2 Swedish family policy in a comparative perspective

My study exploited two facts: (1) Swedish family policies were markedly extended from the early 1960s to around 1980, and (2) the extension of policies exceeded policies implemented in neighbouring countries. I also emphasised that the policies largely reduced one specific component of the cost of children, namely, women’s private opportunity cost of children. In this section, I start by describing the evolution of family policies in Sweden during this period.Footnote 1 Afterwards, I briefly compare this policy change with the changes in neighbouring countries.

Table 1 provides an overview of Swedish family policy implementation from 1960 onwards. Columns 1–4 describe policies that in some way help women to combine working careers and children; the benefits of the policies depend on previous or current labour market activity. Column 5 describes cash support to families with children, a support that does not depend on labour market activity.

In 1960, Swedish women had the legal right to 6 months of unpaid leave after giving birth, and it was already illegal to dismiss a woman because of having children. Since the mid-1950s there was also a paid maternity leave scheme that offered pay for 3 months at a flat rate; typical female workers were compensated by about 60% of foregone earnings. In 1963, the paid maternity leave scheme was extended to 6 months, and the benefit became loosely tied to foregone earnings, with a replacement level about 65%.

Major extensions of this leave scheme then occurred on different occasions from 1974 onwards. In 1974, the scheme was changed to a parental leave system, although mothers continued to use the bulk of paid leave opportunities.Footnote 2 The benefit level was also raised to 90% of foregone earnings, with eligibility based on earnings in the 240 days prior to giving birth. Those who did not fulfil this requirement instead received a low flat rate. Further, there was an upper limit on the benefit, but as this level was quite high, most women still had a replacement rate of 90%. The major system change in 1974 made benefits taxable, and the benefits counted as an income source that gave future pension rights.

A series of extensions of the benefit period then followed. In 1975 the period was 7 months; in 1978, 8 months plus 1 month at a low flat rate; in 1980, 9 months plus 3 months at a low flat rate; and in 1989, 12 months with a 90% replacement rate plus three additional months at a low flat rate.

The Swedish rules that determine maternity leave benefits also contain elements that create a kind of “speed premium” on further childbearing. Because maternity leave benefits are earnings-related, a period of no work or only part-time work after a birth would reduce the benefit level after a subsequent birth. However, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, the rules became successively more generous, allowing the parent to retain the right to the benefit level that she once had obtained by working full time before the first (or any previous) birth. From 1974 to 1979, the parent could abstain from earning for 12–18 months (depending on local application of the rules) and yet retain the right to a previous benefit level for subsequent births. From 1980 to 1985 the interval became 24 months, and this was prolonged to 30 months in 1986. From 1980 onwards, there was no local variation in the rules.

The effect of these policies was that the mother did not have to work full time to qualify for high benefits for the second child or for subsequent children, conditional upon close spacing of their births, thus, the label speed premium. It was the authorities, rather than politicians, who determined these rules concerning practical implementation of the scheme. Therefore, one cannot claim that politicians deliberately created incentives for the close spacing of children.

Local-government-subsidised child care in care centres is another important feature of Swedish family policy. In the early 1960s only some part-time options were offered, but from the late 1960s onwards, a major extension occurred. Because local governments have been the major providers of child care, there has always been some variation in coverage and rules, but the general ambition has been to provide care that allows both parents to work full time. Further, child care has been heavily subsidised, with fees only covering about 10–20% of all costs, and these fees were often on a falling scale for the second child and for subsequent children. However, only families with two working (or studying) parents have been eligible for this subsidised care. Although the supply of care slots increased quickly over this period (see Table 1), there has often been excess demand for the slots. Techniques used to handle this situation have varied among local governments. Families on social assistance (often single mothers or families with special needs) were generally given priority if there was a queue for child care.

Besides care for preschool children, local governments provide subsidised before- and after-school care for children up to about age 10 (the school starting age is 7 in Sweden). This care also rapidly increased over the same time period.

In most local communities, the structure of the fees for before- and after-school care also created a kind of speed premium. In general, families with more than one child in public day care at the same time were offered much lower fees for the second child and for subsequent children. Thus, the total day care costs for raising a certain number of children were much lower for closely spaced children than for more widely spaced ones. The main motivation for this fee structure could hardly have been to create a speed premium for childbearing, yet such an effect was created.

Employees who work at both types of child care facilities have been adequately trained for these jobs. Typically, they have had 2 years of special training after high school. Therefore, the number of schools for these occupations increased during this period, and the positions (förskollärare at day care centres and fritidspedagog at the before- and after-school care centres) became well-known, certified occupations.

Column 3 displays the pay for the temporary care of sick children. This benefit was introduced as part of the changes in 1974. At first, 10 days of paid leave per year for the care of a sick child covered up to 90% of foregone earnings. In 1980 the number of days was increased to 60 a year, and in 1989–1990, this was further increased to 90 a year. This benefit arguably helps alleviate the stress associated with having young children and a job in the labour market. For example, parents need not use their vacation days to take care of sick children.Footnote 3 Neither do they need to pay for expensive care for a sick child. In the 1960s, families probably used vacation days for these purposes if both parents had a job (and other child care services could not be obtained). From 1974 onwards, however, parents did not have to sacrifice any of their mandatory four vacation weeks to take care of sick children.

Sweden also used labour relations legislation to facilitate the combination of childbearing and mothers participating in the labour market. In 1979 the Parliament took an important decision that gave young children’s parents the right to cut back their working hours from full time to 75%. This right makes it easier for parents to take part-time leave. Parents can exercise this right until their children reach the age of 8.

The major form of cash support for families with children is the universal child allowance that was introduced in 1948. A non-taxable fixed amount per child is paid each month to the mother. As shown in column 5 of Table 1, the real value of this benefit increased during the period. In 1982, a higher amount for the third child and for subsequent children was introduced. Besides this universal allowance, families with children can become eligible for means-tested housing allowances and social assistance benefits.

The other Nordic countries also extended their family policies over this period, but not as much as in Sweden.Footnote 4 The uniqueness of Swedish policy is most marked for the policies shown in Table 1, columns 1–4. The duration of the parental leave right was longer in Sweden than in Denmark, Finland, and Norway during the 1970s and 1980s. It also remained somewhat longer during the 1990s. Parental leave rights were more flexible in Sweden because the rights could be used over a longer period and combined with part-time work. Here, employment legislation complemented the parental leave system.

Compared to other Nordic countries, Sweden’s parental leave system has been relatively less generous for women who had not worked before childbearing. The minimum benefit level in Sweden’s parental leave system has been very low compared to minimum benefit levels in the other countries.

Sweden also had a more generous care-centre policy than Finland and Norway, whereas Denmark was quite close to Sweden. Finally, no other Nordic country has been as generous as Sweden regarding working families’ rights to stay home and care for sick children. So when it comes to family policy that helps families combine work with having children, Sweden clearly dominates its three Nordic neighbours. It is also well known that Sweden also dominated most other European countries in this respect. In my subsequent cross-country comparison of fertility patterns, I use data from Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, France, and the UK. Therefore, my claim about dominance refers to these countries.

It is less obvious how the comparison turns out when various types of cash support are also accounted for. It could well be that Sweden does not dominate all other countries in extending support to families with children when such cash support also enters the picture. Such cash support takes many different forms in different countries, so it is a huge task to make a comparison in this respect. Fortunately, Wennemo (1994) carried out the time-consuming work of estimating the value of tax credits, cash benefits, and tax allowances in several Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries over the time period on which I focus.

Table 2 reports some results from her inquiry for 1960, 1970, 1980, and 1985. The value of the benefits is expressed as the share of the net income of an average industrial worker. As expected from the information in Table 1, the average value of these benefits increased in Sweden. Most important for my research strategy, however, the other countries did not dominate Sweden in the sense that they extended this kind of support substantially more than Sweden did. It is rather the case that Sweden also dominates most other countries in this dimension.

Thus, my general conclusion was that the period from the early 1960s to around 1980 was a time when Sweden extended its policies to families with children more than its neighbouring countries. Sweden was particularly unique because its policies cut child-related costs that were associated with foregone earnings for parents (usually mothers) who would have stayed home to care for their children.

3 The economic incentives created by family policy

The main reason why family policy could affect the level of completed fertility is that such policies cut the cost of having a child. For a discussion about family policy and the cost of a child, it is useful to follow the analysis of Walker (1995). His model breaks the cost of having a child into three components. The first cost component is foregone earnings for the parent who must abstain from paid work to care for the child. This cost component is reduced by the earning-related parental leave benefit and the benefit from staying home to care for a sick child. One can also consider subsidised child care as a way of reducing this cost of having a child.

The second cost component consists of direct costs to raise the child, e.g. costs for food, clothes, housing, and child care. These costs are lowered by the universal child allowance and subsidised child care.

The third cost component was loss of human capital accumulation due to interruption of labour market participation. No part of Swedish family policy compensates for such costs of having a child. Of course, child care arrangements help parents combine children with labour market participation and, thus, reduce this cost of having a child. However, the generous parental leave benefits stimulate parents to stay home at least for slightly over a year (in full-time equivalents).

The main presumption in the economics of fertility is that a reduction of the cost of having a child will raise fertility.Footnote 5 Because Swedish family policy has had such a strong focus on reducing the cost associated with foregone earnings, this impact is not necessarily neutral with respect to women’s socio-economic or labour market status. Indeed, women who in any case would not have entered the labour market do not benefit as much as other women, and thus, their fertility behaviour is unlikely to be as much affected. Ermisch (1989) offered a formal analysis of the impact of child care costs on the association between the potential wage and preferred fertility, and his results confirm that the impact of child care on preferred fertility need not be neutral with respect to the potential wage. Thus, it could be that the extension of Swedish family policies has changed the socio-economic structure of fertility.

The policies could also affect timing of childbearing, i.e. the age at which women decide to have children. To be eligible for the bulk of benefits that Swedish family policy offers, it is important to have become reasonably well established on the labour market. The parental leave benefit is earnings-related. Thus, women who have not worked full time or women who have had a low monthly salary the year before childbearing receive lower benefits for the entire parental leave period. Much anecdotal evidence suggests that a typical strategy for women in Sweden who plan to have children is:

-

1.

Complete your education.

-

2.

Get a job and work full time for at least half a year. Ensure that you get a permanent position so that you can return to your employer after parental leave.

-

3.

Have your first child.

-

4.

Work part time for a while, and use subsidised day care until you have your next child.

Because of the policies, I expect that in Sweden, the average age for first births became higher than it would have been without implementation of the legislation.

Finally, one could expect that the policies have affected the spacing of children in instances when women planned to have more than one child. The spacing effect could be enhanced by the way in which the authorities implemented the law, the so-called speed premium discussed earlier. Note also that these rules made it even more important for women to work full time and get a decent salary before having the first child. By qualifying at a high benefit level once (before the first child) it is possible to keep the high benefit level for several periods of parental leave.

4 The empirical strategy

Massive expansion of family policies from the mid-1960s to around 1980 obviously implied a marked change in economic incentives that women (and men) in Sweden faced when planning for children. The difference is particularly large between those who planned childbearing according to the pre-1963 policy and those who did so according to the post-1980 policy. Women born during the 1920s and the first part of the 1930s belong to the first group. Women born in the 1950s belong to the second group. We can consider women born in the late 1930s and the 1940s as an intermediate case.

Because of rapid policy change, one could argue that a simple before–after comparison would be useful for inferring effects of policy changes, but during the 1965–1980 period, many other changes occurred, and these changes could have had effects on fertility patterns. For example, new birth control methods such as the pill and the intrauterine device (IUD) became more prevalent. Abortion laws were liberalised as were laws governing divorce.Footnote 6 One could also imagine that 1965–1980 was a period of marked changes in attitudes towards the family, having children and sexual activity.

Now, it could be argued that most of these changes also occurred in other countries. However, remember that at the same time, family policy changes were particularly striking in Sweden. Therefore, it then follows that a difference-in-differences approach for estimating family policy impact on fertility would make sense.Footnote 7 This approach allows each country to have its own country-specific fertility level, which could be deeply rooted in traditions and religious attitudes. Further, the countries are assumed to share common time effects, for example, because of general changes in birth control methods and abortion laws. Finally, there is a difference in the evolution of family policies, the impact of which we want to infer.

A second feature of my empirical strategy is that I use data on completed cohort fertility. The typical disadvantage of using this fertility concept is that one must wait until the cohort of women has become old enough to have completed childbearing, i.e. reached the age at which they have become infertile. In my case, this disadvantage is not that strong because I can observe the completed fertility of cohorts of women in Sweden born through the late 1950s. In this way, I include cohorts who could plan their childbearing according to the extended Swedish family policy. More specifically, I use data for the cohorts born through 1958, and their fertility is observed through 2000 (if not otherwise stated). Women in Sweden, born between 1945 and 1955, gave birth to less than 1% of their children after age 42.

For my purposes, the main advantage from using completed fertility rates is that I eliminate all complications caused by changes within countries and differences between countries regarding childbearing age. It is well known that noticeable childbearing-age changes occurred over the period that I studied.Footnote 8 It is also noteworthy that a standard static economic model of the demand for children abstracts from the timing and spacing of children, so such models should, in the first place, predict the outcome of completed fertility.

A final methodological consideration concerns the causal relationship between fertility on one hand and family policy on the other. My analysis is based on the assumption that a generous family policy has a causal effect on fertility. However, there could also be causal effects in the other direction. One possibility is that a large electorate of families with children votes for a policy that is generous to these families. Another is that low period fertility rates motivate a pronatalistic policy. In the former case, there would be a positive association between family policy and fertility rates. In the latter case, there would be a negative association.

Wennemo (1994) discussed these issues and performed a statistical analysis of 18 OECD countries covering the 1947–1985 period. She regressed the size of family support on potential determinants such as gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, left-wing party power, religious party power, and the fertility indicator average, gross reproduction rate. The fertility variable gets positive coefficients in an equation that explains family cash support and in an equation for tax allowances, but a significant one only in the latter case. If interpreted causally, Wennemo’s result suggests that a large electorate of families with children vote for a family-friendly policy. However, the reverse causal structure, namely, that family-friendly policy affects fertility, is also compatible with her findings.

Wennemo’s result does not support the view that low fertility rates trigger a more generous family policy. This judgement is strengthened by the fact that pronatalistic arguments were seldom used in Swedish political discussion when major extensions of family policy were decided. Instead, the promotion of gender equality in the labour market was the major goal for these policies.

5 Results

5.1 The level of fertility

We start with the most central issue, namely, the impact on the level of completed fertility. Figure 1 shows (in three separate parts) the evolution of cohort fertility rates for women born between 1925 and 1958 (or somewhat shorter periods for some countries). The Swedish rates are remarkably stable, around 2.0 over this period. A before–after perspective suggests that there were no effects from the distinct extension of family policies.

Completed fertility rates by birth cohorts 1925–1958. See Appendix for sources

By adopting a difference-in-differences approach, however, we reach another conclusion. In all other countries, cohort fertility rates declined, and in some countries, they declined considerably. We start by comparing Sweden with its Nordic neighbours. An application of the difference-in-differences approach means that the stable cohort fertility rate in Sweden is compared with declines from the early 1930s to the 1950s by about 0.4 in Finland and Norway and 0.5 in Denmark. Therefore, these are my “point estimates” of the effects on the level of fertility of the more generous family policy in Sweden compared to the other countries. The corresponding comparison with the other European countries gives somewhat larger magnitudes of the estimated effects.

The basic assumptions behind these estimates are obviously strong. In particular, one could suspect that there are additional time-varying factors that have been favourable to fertility in Sweden but not in the other countries. Nonetheless, it is striking that Sweden is the only country with a stable cohort fertility over this period.

5.2 A digression on the low fertility rates in Sweden in the 1990s

The conclusion in the previous section might sound strange for those who have followed the Swedish experience and discussion since the early 1990s. After a peak of 2.14 in 1990, the period total fertility rate declined sharply to 1.50 in 1999 and has recovered to 1.65 in 2002.Footnote 9 (see more below in Fig. 7). Is this development really consistent with the conclusion that Swedish family policy has permanently raised the completed fertility rate?

To shed light on this issue, Fig. 2 reports the completed fertility rates of Swedish women born through 1965. Children born through 2003 are also accounted for in these data. The figure shows that women born as late as 1965, whose childbearing through age 38 is captured in the data, have already reached the quite high level of 1.87. Therefore, it seems reasonable that the prospects of reaching a completed fertility rate close to 2.0 are quite good for women born through 1965. However, low fertility rates during the 1990s suggest that women born after 1965 must space their children very closely to reach the fertility level of the preceding generations of women.

Completed fertility rates for Swedish women born from 1940 to 1965. Source: special tabulations from Statistics Sweden’s population registers. These numbers include foreign-born women and thus differ somewhat from those in other figures. However, the basic level is the same. The numbers include births through 2003

5.3 Fertility by educational level

Because Swedish family policies facilitate labour force participation for women, the policies help reduce costs that are associated with foregone earnings. Thus, the policies can be expected to be particularly valuable for women with high earning capacity. In this section, I used educational level as an indicator of earning capacity. My main purpose is to investigate whether the fertility rates among highly educated women in Sweden, compared to less-educated women, have evolved differently from those in other countries.

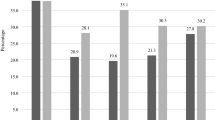

Figure 3 presents a series of graphs with completed cohort fertility rates by education groups for women in Sweden and four comparison countries. In interpreting this information, two complications should be considered.Footnote 10 First, there might be a two-way causation process involved because a woman’s educational level might affect subsequent childbearing, and an early-born child could affect subsequent education plans. To reduce this problem, I tried to acquire data on women’s educational level around age 45. Second, the educational achievement of women has increased a lot over time, so in all countries, the number of women in the higher education group has increased.

A general pattern for all countries, including Sweden, is that completed fertility is negatively associated with educational level. Therefore, this seems to be a very robust pattern. It is also consistent with the negative effect of women’s wage rates on the fertility level found by Heckman and Walker (1990). For all countries we can also note that this educational pattern is stable over time.Footnote 11 The long-run decline in completed fertility rates in Belgium and France is found among all women regardless of education level.

5.4 Timing

Sweden’s family policy creates an incentive for women to first finish their education and then get established in the labour market before having children. Thus, we would expect cohorts of women born in the 1950s to have delayed childbearing compared to the cohorts of women born in the 1930s.

Data on first-birth age reported in Figs. 4 and 5 show that a before–after perspective on the Swedish experience strongly supports this hypothesis. Figure 4 shows that the average age of women at the birth of their first child time increased from about age 24 for cohorts born in the mid-1940s to over 26 for the 1958 cohort. The conclusion that family policies of the Swedish type lead to a postponement of childbirth would be strengthened if a difference-in-differences approach also supports this hypothesis. However, a closer glance at the data in Fig. 4 suggests that there is no striking difference between the evolution in Sweden and in the other countries for which I was able to acquire data. There is a U-shaped pattern in data for all six countries, with lows in the mid-1940s. Since then, the age at first birth has increased in all countries.Footnote 12 In particular, the increase in the Netherlands is marked despite a family policy that is very different from Sweden’s.

Age at birth of first child by birth cohorts. See “Appendix” for sources

Age at birth of first child by final parity. See “Appendix” for sources

Because first-birth age and completed fertility are negatively associated, one would expect that average first-birth age rises in a country with falling fertility rates. Thus, in countries with falling fertility rates, one would expect a composition effect such that the fraction of women with few children and high first-birth age increases over time. To avoid this problem, I have collected data on first-birth age by final parity. The results in Fig. 5 confirm that first-birth age falls with the rising number of children born for the four countries (Sweden, Denmark, France, and Norway) for which I was able to acquire data. Crudely, the age falls by 1.5–2.0 years for each unit of family size.

Because of this pattern, one could expect that for all countries except Sweden, the composition effect partly drives the numbers in Fig. 4. The data in Fig. 5 for the Netherlands show that first-birth age also increased very much for the parity one. There is, however, a clear pattern in which the parity-specific age at first birth in Norway has not increased as much as in Sweden. The same applies to Denmark, although not as strongly.

To recap, this analysis has shown that the postponement of first birth has been strong in Sweden and stronger than in Denmark and Norway. These differences lend some support for the hypothesis that family policy matters. Nonetheless, the fact that the rise in first-birth age has been even stronger in the Netherlands suggests that other forces are also important.

5.5 Spacing

Finally, one could expect that the speed premium created by the Swedish rules has stimulated women to space children more closely. We would expect that the intervals between births declined more for Swedish women than for women in other countries, and we would expect to see the decline when we study cohorts of women born from the 1940s to the late 1950s.

Data in Fig. 6 show that the time interval between a woman’s first and last child declined from 1950–1954 to 1955–1958. The magnitudes are about 0.3 year for women who had two children, 0.6 year for women who had three children, and 0.9 year for those who had four children. Therefore, the before–after comparison lends support for the hypothesis. The data in Fig. 6 also allow me to adopt the difference-in-differences approach by comparing Sweden with Denmark and Norway. This approach further supports the view that Swedish family policy had an effect on the spacing of births. Whereas the time intervals for all final parities increased from 1945–1949 to 1950–1954 in Denmark and Norway, they were stable in Sweden. And from 1950–1954 to 1955–1958, the intervals continued to increase in Norway but diminished in Sweden.

These results corroborate the findings from micro-econometric duration analysis reported by Hoem (1993). My more descriptive approach, however, helps put the effects in some historical and cross-national perspectives. Indeed, the dip in spacing is not that striking in such perspectives. The figure shows that the dip roughly corresponds to a return to the spacing intervals of Swedish women born in the 1930s. Further, the cross-national comparison shows that the spacing intervals of Swedish women born during the 1950s were quite close to those of French and Norwegian women born during the 1930s and 1940s. All in all, my results have, on one hand, added to the previous evidence that there really are speed-premium effects of Swedish family policy. However, on the other hand, the magnitudes of the effects are not so strong that they have made family structures much different from what they were only a couple of decades ago.

5.6 Fluctuations in aggregate fertility rates

The data presented so far suggest that there are some noticeable time-series fluctuations in Swedish aggregate fertility rates. Such fluctuations are of interest in their own right. There is ample evidence in the literature that fluctuations in fertility rates have important societal consequences. For example, most studies indicate that the size of a cohort has an impact on the cohort’s labour market prospects (see, for example, Klevmarken 1993). Therefore, we should consider whether there are reasons to believe that the fluctuations are related to family policies.

The total fertility rates (Fig. 7) definitely suggest that there is something special with Sweden in this respect. Swedish fertility rates rose during the prosperous 1980s and fell dramatically during the severe recession in the 1990s. The decline lasted through 1999, followed by recovery in 2000, 2001, and 2002 when the labour market had improved. Among other Nordic countries, Denmark shows some fluctuations in its fertility rates, but these fluctuations are not as closely related to the labour market as in Sweden. Also, note that Finland’s fertility rates did not respond to the severe labour market shock in the 1990s; the rise in unemployment was even stronger than in Sweden. Further, there are no signs that the period total fertility rates in other North European countries responded to the labour market shocks in these countries during the 1980s and 1990s (see the lower panel in Fig. 7).

The hypothesis that family policies cause (or at least aggravate) fluctuations in Sweden’s fertility rates cannot be tested with high statistical power. There are too few marked labour market cycles during the period (with generous family policies) for a powerful test. Nonetheless, this hypothesis makes sense and is consistent with the data. In a poor labour market, it takes longer to get a permanent job with a good salary that qualifies for the full benefits offered to parents by Swedish family policies. In the 1990s, Finland’s family policy had become quite similar to Sweden’s, but there were some important differences in policy design. For example, in Finland, benefits for parents who had not worked full time before having a child were not dramatically lower than for a family that had done so.

6 Conclusions

When I started collecting the data I presented in this lecture, I had expected to see some noteworthy deviations between Sweden and its neighbouring countries. I must also admit that these expectations were formed by my belief that economic incentives, such as those created by Sweden’s family policy, really affect the level and structure of fertility. My prior beliefs were strongest regarding timing and spacing of children. Previous micro-data analyses have quite convincingly shown that Swedish women have responded to the so-called speed premium to close spacing of children induced by the rules of the parental leave benefits. Indeed, my cross-national analysis confirms that Swedish women’s spacing patterns evolved differently from women in Denmark and Norway when these rules were implemented. Nonetheless, in a more historical perspective, the spacing pattern of Swedish women born in the late 1950s was not very much different from their mothers born around 1930 and from the one of French women born around 1930. Thus, one cannot argue—as is sometimes done in Swedish public discussion—that the impact of the speed premium is a marked one that has created new kinds of family structures.

Swedish total (period) fertility rates have also revealed stronger fluctuations than those of other countries. In particular, Sweden’s fertility rates were very sensitive to the severe labour market shocks that occurred in the 1980s and 1990s. The contrast to Finland, which suffered from similar (or even stronger) labour market fluctuations during the same decades, is particularly strong. My interpretation is that this instability is enhanced by the family policy that creates strong incentives to delay childbearing until the woman (and, in a few cases, the man) has worked full time for almost a year.

I was surprised to see that the cross-national differences-in-differences suggest such a strong impact on the overall fertility level of the Swedish family policy. The stability of Swedish completed fertility rates for women born from around 1930 until around 1960 and the significant decline for the same cohorts of women in all other neighbouring countries could be interpreted as if the very generous family policy prevented the substantial decline of fertility rates that occurred in the other countries. However, needless to say, the statistical power of this conclusion is not that high; other period-specific factors in Sweden could also explain why its fertility rates evolved differently from the other countries.

In one important respect, however, one cannot see any effects of family policy, namely, the association between women’s educational level and completed fertility. Although one could expect that the impact of family policy on fertility would not be neutral with respect to educational level, this pattern has been remarkably stable in Sweden during the period of time when family policy was extended so much. More or less, the same negative pattern is visible for women born around 1930 and in the late 1950s. Furthermore, the decline in fertility rates in other countries can be seen at all educational levels. Thus, the negative association between educational level and completed fertility seems to be a stubborn one that has survived both marked policy changes and dramatic changes in women’s labour force participation.

Notes

See Sundström and Dufvander (2002), who show that the fraction of paid days used by fathers never exceeded 11% over the 1974–1990 period. They also perform an interesting statistical analysis of the determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ use of the leave.

Because of this policy, care centres can require that a sick child be kept home instead of coming to the centre with an obvious risk for contagion.

See Hoem and Hoem (1997) for an informative account of such policy changes.

See, e.g. Angrist and Krueger (1999) for a formal presentation of the difference-in-differences approach.

See, e.g. Gustafsson (2001).

Monthly data through December 2003 show that the recovery has continued, and seasonally adjusted figures in the fall of 2003 reached around 1.75.

Data for Denmark and the Netherlands, available from the author upon request, show the same pattern.

For Sweden one can see some reduction in the differentials by education level through the early 1950s, followed by some increase again during the rest of the 1950s. A very detailed analysis might find that the association between education level and completed fertility level has changed over time. Such a more detailed analysis would have to consider that the length of the educational levels have changed over time as well. My only claim in this paper is that the introduction of an extensive family policy has not eliminated the negative association between completed fertility and education level.

References

Angrist JD, Krueger AB (1999) Empirical strategies in labor economics. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3A. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Birg H, Filip D, Flöthmann E-J (1990) Paritätsspezifische Kohortenanalyse des generativen Verhaltens in der Bundesrepuplik Deutschland nach dem 2. Welkrieg. IBS-Materialen Nr. 30. Institut für Bevölkerungsforschung und Sozialpolitik, Universität Bielefeld, Bielefeld

Bosveld W (1996) The aging of fertility in Europe. A comparative demographic-analytic study, PDOD. Thesis, Amsterdam

Brunborg H, Mamelund S-E (1994) Kohort-og periodefruktbarhet i Norge 1820–1993. Rapporter 94/27 SSB, Oslo

Council of Europe (2001) Recent demographic developments in Europe 2001. Council of Europe, Strasbourg

Council of Europe (2003) Recent demographic developments in Europe 2003. Council of Europe, Strasbourg

Daguet F (2000) L’évolution de la fécondité des générations nées de 1917 à 1949: analyse par rang de naissance et niveau de diplôme. Population 2000(6):1021–1034

Ermisch J (1989) Purchased child care, optimal family size and mother’s employment. J Popul Econ 2:79–102

Gauthier AH (1996) The state and the family: a comparative analysis of family policies in industrialised countries. Clarendon, Oxford

Gustafsson S (2001) Optimal age at motherhood. Theoretical and empirical considerations on postponement of maternity in Europe. J Popul Econ 14:225–247

Heckman J, Walker J (1990) The relationship between wages and income and the timing and spacing of births: evidence from Swedish longitudinal data. Econometrica 58:1411–1441

Hoem JM (1993) Public policy as the fuel of fertility. Acta Sociol 36:19–31

Hoem B, Hoem JM (1997) Sweden’s family policies and roller-coaster fertility. J Popul Problems 52:1–22

Hotz VJ, Klerman JA, Willis RJ (1997) The economics of fertility in developed countries. In: Rosenzweig MR, Stark O (eds) Handbook of population and family economics. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Klevmarken A (1993) Demographics and the dynamics of earnings. J Popul Econ 6:105–122

Lappegård T (2000) New fertility trends in Norway. Demographic Research, vol 2/3. http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol2/3

Rönsen M, Sundström M (2002) Family policy and after-birth employment among new mothers—a comparison of Finland, Norway and Sweden. Eur J Popul 18:121–152

Sainsbury D (1996) Gender equality and welfare states. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Schultz TP (2001) The fertility transition: economic explanations. In Smelser NJ, Baltes PB (eds) International encyclopedia of the social sciences. Elsevier, Oxford

SOU (1989) Arbetstid och välfärd. Betänkande av arbetstidskommittén. SOU 1989:53

Sundström M, Dufvander A-Z (2002) Family division of child care and the sharing of parental leave among new parents in Sweden. Eur Sociol Rev 18(4):433–447

Walker JR (1995) The effect of public policies on recent Swedish fertility behavior. J Popul Econ 8:223–251

Wennemo I (1994) Sharing the costs of children. Dissertation series no. 25, Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University, Stockholm

Acknowledgements

This is a revised and updated version of my presidential address at the ESPE-2001 meetings in Athens. I am grateful to several national experts for help and advice with data collection for this paper. By country, these are Belgium, Ron Lesthaeghe; Denmark, Lisbeth Knudsen, Jørn Korsbø Petersen and Nina Smith; France, Fabienne Daguet; Germany, Michaela Kreyenfeld and Thorsten Schneider; Netherlands, Gijs Beets and Jan Latten; Norway, Helge Brunnborg and Trude Lappegård; and Sweden, Gun Alm-Stenflo and Elisabeth Landgren-Möller. I also thank Gunnar Andersson, Thomas Aronsson, Lena Edlund, Jan Hoem, Per Molander, Marianne Sundström, and Mårten Palme for many valuable discussions about the paper’s topics. Three referees provided most valuable comments. Despite all help and suggestions, the usual disclaimer applies. Swedish Council for Social Research and Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research provided financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Data sources

Figure 1. Data for Sweden were obtained from special tabulations from Statistics Sweden’s population registers. Only women born in Sweden are included. Data for other countries were obtained from Council of Europe (2001). Births through age 42 are recorded.

Figure 3. For Belgium, data were obtained from census-based data in table A9.3 in Monografie nr. 5B (2000) Ministerie van Economische Zaken. Daguet (2000), plus more detailed data provided by her, supplied the information for France. For Germany, tabulations from the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP) were made for me by Torsten Schneider. For Norway, the sources were Brunborg and Mamelund (1994), Lappegård (2000), and unpublished data from Statistics Norway. Finally, for Sweden, data came from special tabulations from Statistics Sweden’s population registers merged with the education register.

Figures 4, 5, and 6. Computations for Denmark were obtained from the Fertility Data Base provided by Jørn Korsbø Petersen. Daguet (2000), plus more detailed data provided by her, supplied the information for France. Data for Germany came from Birg et al. (1990) and Kreyenfeld (unpublished data). For the Netherlands, register-based estimations were provided by Jan Latten. For Norway, the sources were Brunborg and Mamelund (1994), Lappegård (2000), and special tabulations from Statistics Norway. For Sweden, data came from special tabulations from Statistics Sweden’s population registers. As for the UK (England and Wales only), data were provided by the Office of National Statistics, Birth Statistics 1999, Table 10.3.

Figure 7. Council of Europe (2003) and national statistical offices provided the data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Björklund, A. Does family policy affect fertility?. J Popul Econ 19, 3–24 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0024-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0024-0