Abstract

The claim that partisanship has developed into a social identity is one of the dominant explanations for the current rising levels of affective polarization among the U.S. electorate. We provide evidence that partisanship functions as a social identity, but that the salience of partisan identity—in and of itself—does not account for increased affective polarization. Using a two-wave panel survey capturing natural variation in the salience of politics, we find that partisanship contributes more to individuals’ self-concept in times of heightened political salience. We also show that partisans can be detached from their Democratic or Republican identity by having them focus on individuating characteristics (by way of a self-affirmation treatment). However, we find only limited evidence that when partisan social identity is made less salient, either by way of natural variation in political context or through a self-affirmation treatment, partisans are any less inclined to express in-party favoritism and out-party hostility. Taken together, our evidence shows that partisanship does operate as an important social identity, but that affective polarization is likely attributable to more than the classic in-group versus out-group distinction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The polarization of American politics is glaringly apparent. The evidence concerning the increased ideological extremity of party elites is unequivocal (Fleisher and Bond 2001; McCarty et al. 2006; Hetherington 2002). While the extent to which the mass public has followed suit remains an open question, there is increasing evidence that the U.S. electorate is at the very least “affectively polarized.” Rank-and-file partisans increasingly harbor intense animosity and ill will toward their political opponents (for a review of the literature, see Iyengar et al. (2019)). The onset of affective polarization coincides with social and geographical “sorting,” which potentially explains the increased correspondence between party affiliation, ideology, worldview and socialization preferences (Levendusky 2009; Mason 2015; Huber and Malhotra 2017; Hetherington et al. 2016; Mutz 2006).

The dominant explanation for increasing levels of affective polarization—that is, both negative and positive partisanship (Bankert 2020)—is that partisanship no longer simply indicates political preferences, but that it has become an important social identity. While previous work did conceptualize partisanship as a social identity (Campbell et al. 1960; Greene 1999; Green et al. 2002), more recent evidence points to a significant strengthening of this identity. Longitudinal survey data, for instance, shows significantly greater parent-offspring agreement on party affiliation (Iyengar et al. 2018), and a stronger sense of social distance between competing partisans (Iyengar et al. 2012). Beyond the survey evidence, numerous studies document behavioral discrimination against opposing partisans ( Iyengar and Westwood (2015); for a recent review of the evidence, see Iyengar et al. (2019)). Still further evidence of the strength of partisan social identity derives from work showing that the partisan cleavage in America has increasingly come into alignment with several other salient social cleavages. Democrats and Republicans differ not only in their politics, but also in their ethnicity, gender, age, and place of residence (Mason 2018a).

Notwithstanding the evidence cited above, it remains to be seen whether the parallel trends over time in the strengthening of partisan identity and increased willingness of partisans to denigrate out-partisans (affective polarization) demonstrates that attachment to partisanship as a social identity, in and of itself, leads to in-party favoritism and out-group denigration, or whether this correlation is confounded. In this paper, we seek first to provide evidence that partisans in fact internalize their “Republican” and “Democrat” identities as an important ingredient of their overall self-concept. We then test whether this internalization of partisan identity is linked to a willingness to denigrate the out-group. In short, we seek to test whether affective polarization is in fact driven by attachment to partisanship as a social identity.

Our objectives in this paper are threefold. First, we show that partisans internalize their party affiliation as an important social identity. We then test whether partisans can be detached from their Democratic and Republican social identities. Finally, we test whether successful detachment from partisan social identity reduces Democrats’ and Republicans’ motivation to elevate the in-group and denigrate the opposing party, i.e. whether detachment from partisan social identity can reduce affective polarization.

We use two experimental treatments to study partisanship as a social identity. First, we use a strategically-timed panel survey to assess fluctuations in partisan identity salience. Following work on other identities, such as ethnicity and gender, we test whether partisans internalize their Democratic and Republican identities to a greater extent when those identities are likely more salient. That is, using a two-wave panel study, we test whether attachment to partisan social identity is stronger in the midst of a heated election campaign than it is during periods of political “down time,” e.g. during the winter holiday season. Second, drawing on the social psychological literature and self-affirmation theory, we suggest that when individuating (as opposed to group-related) attributes become salient, group affiliations lose some of their hold over individuals’ sense of self. Thus, by embedding a self-affirmation treatment within our two-wave panel study, we test whether focusing on individuating characteristics can reduce attachment to partisan identity. Using both our panel survey as well as our self-affirmation treatment, we show that partisan social identity is in fact malleable. The extent to which Democrats and Republicans internalize their partisanship fluctuates according to naturally occurring variability in the salience of partisan cues as well as an experimental manipulation designed to weaken the strength of individuals’ partisan identity.

Our second objective is then to test whether attachment to partisanship as a social identity predicts in-group favoritism and animus toward the opposing party, i.e. whether it is linked to affective polarization. We find that, while partisans can be detached from their Democratic and Republican social identities, this detachment does not, in turn, reliably mitigate out-group animus. This suggests that while partisanship is indeed internalized as an important social identity, weakening the strength of this identity will not necessarily reduce out-party animus during times of heightened political salience.

We advance the literature on partisan polarization as follows. First, while partisanship is often conceptualized as a social identity (Tajfel and Turner 1979), our results provide direct evidence that partisans in fact internalize the sense of party identification as an important component of their self-concept. Second, we break new ground by showing that partisan social identity fluctuates with the salience of the political landscape. Third, we are the first to show that the partisan component of the self-concept can be diminished through a focus on individuating characteristics. Finally, we contribute to the burgeoning literature on partisan affect (Abramowitz and Webster 2016; Iyengar et al. 2019, 2012; Mason 2013, 2018a; Huddy et al. 2015; Druckman and Levendusky 2019; Levendusky 2018b) by showing, contrary to expectations, that out-group bias persists even when attachment to partisan identity is diminished, suggesting that factors other than “partyism” (Sunstein 2017) must also contribute to polarization.

Affective Polarization and Partisanship as a Social Identity

The most recent manifestation of the nation’s divide along partisan lines—termed affective polarization—has emerged over the past three decades. Beginning in the mid-1980s, national survey data document that Democrats and Republicans express disdain for candidates of the opposing party, and also hold pejorative stereotypes of opposing partisans (Iyengar et al. 2012; Hetherington et al. 2016; Iyengar and Krupenkin 2018). If partisanship is internalized as a social identity—that is, it represents an important part of one’s self-concept (or self-image)—then these findings are consistent with social identity theory, which further posits that all forms of identity inevitably engender a sense of in-group favoritism and out-group animosity (Tajfel 1970; Tajfel and Turner 1979; Billig and Tajfel 1973), and that out-group animosity is often a product of identity threat (Brewer 1999; Huddy 2013). However, to date, there is little evidence documenting that the mechanism driving such out-party animus is in fact attachment to partisanship as a social identity.

What is striking is the extent to which the us-versus-them divide based on partisanship far outstrips other divides associated with alternative group affiliations. In the case of race, historically considered the deepest divide in American society, recent ANES survey data show that evaluations of racial groups differ only modestly across respondents of varying racial backgrounds. The same non-polarized pattern applies to group evaluations surrounding religion, region, socio-economic status, and gender (see Iyengar et al. (2012)). Out-group denigration based on race, religion, or gender does not match the level of animus directed at opposing partisans.

Quite possibly, the diminished expression of out-group sentiment based on race or religion might reflect the increased diffusion of societal norms favoring equality and fairness. Yet, the discrepancy between partisanship and other forms of social identity persists when researchers use the most unobtrusive measurement techniques—those least susceptible to normative pressures, impression management, and other forms of distortion (Iyengar and Westwood 2015). Apparently, partisanship is a group affiliation that elicits especially severe evaluations of out-group members. The question we pursue here is whether this out-group denigration is primarily due to the internalization of partisanship as a social identity.

Before turning to our investigation of partisanship as a social identity, it is worth pointing out that behavioral markers of group polarization corroborate the above evidence showing in-group favoritism and hostility in partisan attitudes. In a series of dictator games—in which individuals are given the opportunity to donate a sum of money to another individual—researchers found that partisans imposed a significant penalty on opposing partisans (in the form of smaller donations). Moreover, the bias based on party affiliation exceeded the bias based on other group memberships including race and religion (Iyengar and Westwood 2015; Westwood et al. 2017). All told, the implicit and behavioral tests of out-group discrimination converge; partisan affect dominates affect based on most other identities.

Further behavioral testimony to the extent of affective polarization comes from studies of social interaction. For Americans, an individual’s party affiliation has become a litmus test for inter-personal attractiveness. People prefer to associate and maintain significant relationships with fellow partisans. Dating and marriage studies reveal that partisanship is a key attribute underlying the selection of long-term partners (Huber and Malhotra 2017; Iyengar et al. 2018). The homogeneity of family networks creates a vicious cycle by which partisan sentiments recirculate across generations (Klofstad et al. 2013). Further, social settings have been shown to have an independent effect on partisan behavior (Klar 2014).

Despite mounting evidence that partisanship induces attitudes and behavior that starkly outline group boundaries, few studies directly address the “internalization” of partisanship as a salient social identity in the context of affective polarization and/or increased partisan sorting.Footnote 1 We also lack a nuanced understanding of the circumstances under which this identity might become more or less important to individuals’ self-concept. Further, while mounting evidence seems to suggest a link between partisanship as a social identity and affective polarization, there is little evidence drawing a direct connection between the two. Thus, we seek to empirically test whether (1) periods of heightened political salience strengthen the internalization of partisanship as a social identity; (2) inducing people to focus on their individuating characteristics weakens their attachment to partisanship as a social identity; and (3) detachment from partisan identity decreases affective polarization.

The Internalization of Partisanship as a Social Identity

In order to derive testable hypotheses relating to the above discussion, we first investigate how partisanship contributes to individuals’ overall self-concept. Theories of self-concept and self-image specify one’s “belief about himself or herself” as comprised of different aspects, such as descriptions of one’s body, social roles, personality traits and existential (abstract) statements about oneself (Kuhn 1960; Baumeister 1999). We connect this to the core of social identity theory, which posits that “social identities” are those social categories that have been internalized as important to one’s self-concept (Tajfel 1978; Tajfel and Turner 1979).

Purely individuating characteristics, such as work-ethic, extraversion, and sense of humor, represent a personal identity portion of the self-concept. Group memberships and attachments, such as one’s race, religious affiliation or partisanship represent a social identity input. In terms of partisanship, just as with other group identities, we expect heterogeneity across individuals and contexts in the extent to which partisanship contributes to the self-concept (Onorato and Turner 2004; Chandra 2012). While we seek to explore the extent to which partisanship can be conceptualized as a social identity, it is certainly possible that parts of one’s political identity contribute to self concept as individuating characteristics or personality traits. If so, however, they are likely statements like “I am interested in politics;” and as such, are separate from group-affiliated statements about oneself like “I am a Republican.” Our first hypothesis, therefore, is that in times of heightened political salience—such as during an important national election—partisanship as a social identity will be strengthened and contribute more to individuals’ self-concept than it would during times when the political world is more remote and less visible. Personal ideological considerations may be closer to the personality traits described above, even if they are predictive of attachment to an ideological ‘group’ (Devine 2015; Mason 2018b, c). In either case, we expect these ideological considerations to be more stable over time; and therefore, we do not expect measures of ideology to change significantly during these times of heightened political salience.

We further hypothesize that focusing on one type of input into the self-concept reduces the contribution of other inputs. Our second hypothesis, therefore, is that a focus on personal identity will necessarily weaken social identity elements of the self-concept. Specifically, we are interested in testing whether individuals become distanced from their partisanship as a social identity when they are encouraged to focus on individuating traits associated with their personal identity.

In order to test this account, we rely on a self-affirmation manipulation (Steele 1999). Self-affirmation treatments encourage subjects to focus on individuating characteristics by reflecting on their personal values (see McQueen and Klein (2006) for a review). Thus, we test our second hypothesis by having subjects focus on their personal identity using a self-affirmation treatment, with the expectation that this will serve to distance individuals from salient social identities. Again, if self-affirmations successfully increase the salience of individuating characteristics (i.e. personal identity), we expect that self-affirmations will also reduce individuals’ attachments to their group affiliations (i.e. their social identity).

As previously noted, we also rely on the core postulate from social identity theory; namely, once individuals internalize a group affiliation as important to their self-concept, they then work to maintain a positive self-image by striving to place this identity in its best possible light (Tajfel and Turner 1979; Oakes and Turner 1980). Many researchers have transferred this fundamental concept from social identity theory to self-affirmation theory, showing that self-affirmations can reduce in-group bias that often results from threats to group identity (Steele et al. 2002; Cohen and Garcia 2008; Cohen and Sherman 2014). Of particular relevance here, these self-affirmation treatments may be successful in reducing in-group bias associated with partisanship (Binning et al. 2010; Cohen et al. 2007), although this evidence is inconclusive (Levendusky 2018b). In terms of the underlying mechanism driving these reductions in in-group favoritism, self-affirmations are assumed to offer a buffer against threats to one’s self-concept, some of which may arise from threats to one’s group status (Steele et al. 2002; Steele 1999). However, to date, there is no empirical evidence for these types of mechanisms. In fact, self-affirmations have not been found to systematically increase self-esteem or boost self-image (Wood et al. 2009; McQueen and Klein 2006).

We hypothesize a different mechanism by which self-affirmations reduce group-based bias. We expect that self-affirmations may reduce group-based biases by reducing the extent to which subjects’ social identities contribute to their self-concept. As stated previously, we expect that self-affirmations, by boosting the contribution of personal identity to the self concept, will also reduce the extent to which social identities contribute to one’s sense of self. It then follows that individuals will be less inclined to engage in in-group favoritism and/or out-group denigration so as to maintain a positive self-image—because self-affirmed subjects are now relatively detached from their group identities.Footnote 2 This is reminiscent of the Common Ingroup Identity Model (Gaertner et al. 1993) being used to motivate primes of “supra-identities” to reduce group-based biases. In our context of interest, national identity has been shown to successfully reduce affective polarization (Levendusky 2018a). Our self-affirmation could be considered the other side of this coin, whereby instead of a larger, supra-identity, we have subjects focus on their individuating characteristics as an alternative mode of detaching from their partisan group identity.

In the context of partisan identity, we hypothesize that self-affirmations reduce group-based bias not necessarily because they buffer against threats to group status by boosting self-integrity (Binning et al. 2010), but rather because they focus subjects’ attention on individuating characteristics, allowing them to distance themselves from group attachments. Combining this expectation with our hypothesis that partisan identity is strengthened in times of political salience, we further anticipate that self-affirmation is more likely to reduce in-group bias when partisanship has already been internalized as important to the self-concept. That is, self-affirmation will weaken both (1) attachment to partisan identity and (2) affective polarization to a greater degree during times of heightened political salience.

Thus, our theoretical framework generates the following hypotheses. First, we expect that the extent to which people internalize partisanship as important to their self-concept will be greater during times of political salience (i.e. an important national campaign) than in a period characterized by a preoccupation with family affairs such as the winter holiday season (Hypothesis 1). Second, we hypothesize that making someone focus on their personal identity will reduce the extent to which their social identities contribute to the self-concept. Specifically, we expect that subjects who are given a self-affirmation treatment will be less attached to their partisan identity (Hypothesis 2). Third, we test the corresponding expectations from the extant literature, i.e. that when subjects’ become less attached to their partisan social identities, either by way of our strategically-timed panel survey or our self-affirmation treatment, they also become less likely to express group-based biases. Thus, reducing subjects’ attachment to their partisan social identity will reduce affective polarization (Hypothesis 3). Finally, in times of political salience, when partisanship becomes especially central to the self-concept (H1), we expect that self-affirmation’s weakening of these group ties (H2), will have a particularly strong negative effect on both 1) individuals’ attachment to their partisan identity as well as then 2) individuals’ need to protect their group’s status through either in-group favoritism or out-group denigration. In short, we expect the negative effect of our self-affirmation treatment on affective polarization to be stronger in the first wave of our study, during the 2018 campaign, than in the second wave, during the winter holiday season (Hypothesis 4).

Research Design

We test these hypotheses by running experiments embedded into a two-wave panel survey, the first wave days before the November 2018 midterm elections (11/3–11/7), and the second in late December 2018 (12/22–12/28). This allows for natural variation in the salience of politics and partisanship (Michelitch and Utych 2018).Footnote 3 We also embed, within both of these waves, a self-affirmation treatment, meant to focus subjects’ attention on individuating characteristics. This allows us to test whether individuals who have been encouraged to focus on their personal identity then exhibit both a reduction in the internalization of partisanship (a group identity), as well as whether this, in turn, leads to a reduction in group polarization.

We recruited the sample for our two-wave survey from Dynata’s (formerly Survey Sampling International) national online panel, which provides an online convenience sample that is aimed at being nationally representative on key demographics. Appendix Table 6 provides various descriptive sample statistics on key observable demographic outcomes broken down by party. In general, the samples match up well with the target population on ethnicity, gender, and age.Footnote 4

Given that we expect the self-affirmation effects to occur primarily in Wave 1, we assigned sufficient observations to detect a self-affirmation effect in Wave 1, but then requested that Dynata re-sample only about half of our participants from Wave 1 for Wave 2. We reduced our sample by half in order to detect wave effects, which we predicted would be larger in magnitude relative to the self-affirmation treatment effect.Footnote 5 The resulting sample thus includes 2513 subjects in Wave 1, and 1311 subjects in Wave 2. We have a true panel of 1266 subjects.

Measures

In order to measure the internalization of partisanship as a social identity, we use a battery of questions measuring the partisan self (these questions are often used to measure attachment to other social identities such as race and come from a collective self esteem battery (Luhtanen and Crocker 1992)). The partisan self index is based on an additive index (ranging from 0 to 12) of responses across a set of three questions: “How much do you agree with the following statements (1–5): Being a [Democrat/Republican] is an important part of my self-image; Being a [Democrat/Republican] is an important reflection of who I am; Being a [Democrat/Republican] is an important part of how I define myself.” In terms of internal consistency, the Cronbach’s alpha for these three measures is 0.70; the measures are also similar (particularly the first) to those employed in other studies of partisan identity (Huddy et al. 2015). Appendix Fig. 8 shows the density of responses to this measure in Wave 1 and Wave 2.

As indicators of partisan affect, we incorporate two widely used measures. First, respondents evaluated each party on the standard 0–100 feeling thermometer. Scores of 0 represent extremely “cold” feelings, while scores of 100 represent the opposite and favorable evaluations. Appendix Fig. 9 shows the density of responses to this measure in Wave 1 and Wave 2. Second, we constructed an index of the difference between perceptions of one’s own party’s supporters and supporters of the out-party on four traits: willingness to compromise (1 not at all to 4 extremely well); patriotism (1 not at all to 4 extremely well); narrowmindedness (4 not at all to 1 extremely well) and selfishness (4 not at all to 1 extremely well). The Cronbach’s alpha for the four traits describing Democratic supporters is 0.84, and it is 0.80 for the four traits describing Republican supporters. Appendix Fig. 10 shows the density of responses to this measure in Wave 1 and Wave 2.

The Self-affirmation Treatments

In addition to the natural variation across our two-wave panel design, we randomly assigned subjects (independently within both waves) to one of three treatment conditions, resulting in the 2 \(\times \) 3 factorial design described in Table 1. Given the panel design, we randomly assigned subjects to one of three treatment conditions in the first wave, and then re-randomized them to receive one of these three conditions again in the second wave a month later. Since the self-affirmation treatment is intended to be temporally transient in its impact on subjects’ focus on individuating characteristics, we only analyze the self-affirmation treatment within a given wave, i.e. we do not estimate the effect of self-affirmation assigned in Wave 1 on outcomes measured in Wave 2.Footnote 6

We employed self-affirmation conditions that are designed based on a variation of the canonical treatments used in most self-affirmation experiments (Cohen et al. 2009; Binning et al. 2010; Cohen et al. 2007, 2006; Cohen 2012; Cohen and Sherman 2014; Cohen and Garcia 2008; McQueen and Klein 2006). We adapted the self-affirmation treatments from Napper et al. (2009) which offer more experimental control than the canonical treatments.Footnote 7

Our self-affirmation “ranking self treatment” condition showed subjects a list of values and a brief description of each (e.g. “Wisdom and Knowledge (“Being able to come up with new ideas and ways of doing things is one of my strong points.”)”). Subjects then rated themselves on a scale from 5 “Very Much Like Me” to 1 “Very Much Unlike Me” in terms of how much each of the values related to them. We informed subjects in this condition that “the task is designed to measure your personal strengths” (see Appendix Fig. 4 for screens seen by subjects).

We presented subjects in the “ranking other control” condition with a similar screen showing all the same values as the treatment condition, but instead of applying the values to themselves, subjects ranked their applicability to a group of strangers.Footnote 8 The instruction set for this control condition read as follows: “the task is designed to measure the way in which people make judgments about the personal strengths of other people” (see Appendix Fig. 5 for the screen seen by subjects).

Our third condition was intended to be a “pure” control condition in which subjects merely read through the list of the same values provided in the other two conditions. These subjects did not see the stock image of the group of strangers, nor were they asked to perform any exercise with respect to the values. After reading the list of values, these pure control subjects simply clicked “Continue” (see Appendix Fig. 6 for the screen corresponding to this condition). While we did not expect that simply reading the list of values would have the same effect as the task in our treatment condition (where subjects were asked to rank themselves with respect to these values), our manipulation check results showed that mere exposure to the values did, in fact, affect our subjects. (We assume that while reading the list of values, they automatically thought of themselves as the reference point without being explicitly instructed to do so.) Table 2 shows that, while there were significant differences between our self-affirmation “ranking self” treatment condition and the “ranking others” control condition, the subjects who simply read the list of values (pure control) are just as likely to say that the exercise made them think about themselves as those in the treatment group.Footnote 9 Thus, our preferred specifications combine the subjects in the ranking self treatment and the “values (no ranking)” (originally intended as pure control) conditions, since these subjects all report that the “previous exercise” made them focus on themselves. We then compare these subjects to those in the “ranking others” control condition. As Table 2 clearly demonstrates, the original treatment subjects and the subjects who saw the list of values without a reference group (intended as pure control) are significantly more likely to report having focused on positive aspects about themselves than are those in the “ranking others” control condition. Thus, we are confident that our manipulations were successful, at least in the immediate sense, at manipulating what we intended; that is, we are confident that the comparisons that follow compare treated subjects who focused on positive aspects of themselves to control subjects who did this to a significantly lesser degree.Footnote 10

After subjects completed the initial demographic questions and one of the self-affirmation treatment or control conditions, we informed subjects the survey was complete (see Appendix Fig. 7 for the screen seen by subjects).Footnote 11 Given that online survey panelists are accustomed to taking one survey after another in an omnibus fashion, this allowed us to separate (in the minds of our subjects) the treatment screen from our outcome measures. We then asked a series of outcome measures including both indicators of affective polarization as well as the partisan self battery of questions. Given that our design assigns a self-affirmation treatment independently across two different waves, some subjects were treated in Wave 1, but not in Wave 2, others were treated in Wave 2 but not in Wave 1, and some were treated in both waves or in neither. Table 3 summarizes these treatment assignments across waves.Footnote 12

We turn now to the presentation of results.

Results

We present the sample means for our outcome measures across waves in Table 4, demonstrating significant effects on our partisan self index from the timing of the survey.Footnote 13 There are significant differences in the extent to which partisans internalize their partisan identity between Waves 1 and 2. Clearly, the internalization of partisanship as a social identity is higher during a time of political salience (Wave 1) than it is during a time of relatively low political salience (post-election Wave 2). In fact, these wave effects are significant at the 1% level in a two-sided t-test for both Democrats and Republicans. The magnitude of the effects are similar across party, a decrease of 48% of a standard deviation on the partisan self index among Democrats, and about a 40% decrease among Republicans. We include in Table 4 subjects’ ideological placement on a 7-point scale, liberal to conservative, in order to demonstrate that ideology and partisan social identity are fundamentally separate concepts. It is clear that, although ideology remains completely constant, the heightened political salience during elections significantly increases attachment to partisanship as a social identity among Democrats and Republicans alike.

Despite the significant drop in the salience of partisan social identity from Wave 1 to Wave 2, we find only inconclusive evidence of reduced affective polarization. Table 4 shows that there is a significant reduction in the difference between the feeling thermometer rating of one’s own party and the opposing party between Waves 1 and 2, among both Democrats and Republicans. The magnitude of the effect in the pooled sample is a reduction in the in-out party feeling thermometer of about 14% of a standard deviation. Thus, the magnitude of the effect of electoral timing on the partisan self index is much larger than on this typical measure of affective polarization. This suggests that weakening the role of partisanship as a social identity may have led to reduced affective polarization, but by a much smaller magnitude.

We also find that in the pooled results (both parties) there is a reduction in the difference between in and out party traits index. However, once again the magnitude of this effect is much smaller than the effect on the partisan self index—a decrease in the trait index of about 8% of a standard deviation as compared to 44% of a standard deviation for the pooled sample on the party self index. Further, we do not find consistent support for this result as the difference in the mean trait rating across waves among Democrats and Republicans is not significant. We cannot rule out the possibility that we are under-powered in our partisan sub-samples to detect the negative effect on the party supporter trait index; but we note that we are able to detect effects within the party sub-samples on our other two measures. We also note that wave effects on each of the individual traits in the pooled sample do not reach significance at conventional levels, with the exception of patriotism, and none of the wave effects on these individual traits are significant in the partisan sub-samples (reported in Appendix Table 10). Finally, while we use the difference between in and out party in the main results in order to be consistent with other literature on affective polarization, another way to look at the data is to focus on party animus by examining the trat index for the out-party only. In this case, we note that the wave effects are null across all samples on all measures (see Appendix Table 11).

Both the inconsistency of the effects on these typical measures of affective polarization, and the fact that the effect sizes on these measures are much smaller than the effect sizes on the partisan self index, call into question whether political salience and the strengthening of partisanship as a social identity are the sole drivers of affective polarization. We return to this point later when further analyzing interaction effects.

We turn now to the test of our second hypothesis, that a self-affirmation treatment, by having subjects focus on their personal identity, rather than their group identity, will decrease the extent to which subjects internalize partisanship as important to their self-concept. To analyze these treatment effects, we pool across waves and analyze the effect of being assigned to treatment or control within the present wave. Table 5 shows a significant reduction in Democratic subjects’ internalization of partisanship according to treatment. While this difference between treatment and control among Republicans is also negative, it is substantively smaller (about half the size) in magnitude and insignificant. It is also worth pointing out that, in comparison to the size of the wave effect on this party self index, this self affirmation treatment effect is much smaller, even among Democrats. The self affirmation reduces the party self index by about 18% of a standard deviation among Democrats.

When Democratic subjects focus on their personal identity, it significantly reduces their attachment to partisan identity. This suggests that partisans can be detached from their social identity, at least in a transient fashion, by simply focusing on individuating characteristics. This is in line with other work on social identities, suggesting that individuals’ internalization of their social identities often fluctuates with context, even throughout the course of one’s daily activities (Chandra 2012). Further, this finding is consistent with results from our panel data in Table 4, which also show that partisan identity can be more or less important to one’s self-concept depending on political context.Footnote 14

Table 5 shows insignificant effects of our self-affirmation treatment among Republicans. However, there is suggestive evidence of differences between Democrats and Republicans at the baseline, where Democrats appear to be more affectively charged than Republicans in the control condition. First, the difference in the in-out party feeling thermometer is much higher among Democrats than it is among Republicans (significant at the 1% level) within both waves. And, although just shy of significance, there is a difference of considerable magnitude between Democrats and Republicans on the partisan self index (refer to Appendix Table 6). Taken together, we interpret this as suggestive evidence that Democrats, being weaker than Republicans in terms of control of the federal government, and thus perhaps feeling more “deprived” in a power sense, experience a heightened sense of threat to their partisan identity during our study (relative to Republicans). This could potentially explain why Democrats express their partisan identity more strongly (Riek et al. 2006; Chandra 2012; Brewer 1999). This also, then, may explain why the self-affirmation treatment significantly reduces internalization of partisan identity among Democrats but does so only insignificantly among Republicans—since Republicans are less attached to the identity at the baseline given their position of relative political dominance, the treatment has a weaker effect on them.

Strikingly, while we find convincing evidence that partisans’ internalization of their Democratic and Republican identities can fluctuate significantly, we find inconclusive evidence that these fluctuations correspond with significant changes in affective polarization. As can be seen in Table 4, there is a consistent reduction from Wave 1 to Wave 2 on only one of our measures of affective polarization (i.e. in-out party feeling thermometers), and the magnitude of this wave effect is much smaller than the wave effect on our party self index. While there is a significant reduction from Wave 1 to Wave 2 on the in-out party supporter traits measure in the pooled sample, this effect is insignificant (with a point estimate close to 0) among the samples of Democrats and Republicans. Further, Table 5 shows that the self-affirmation treatment did not have a significant effect on either of our measures of affective polarization, even among Democrats, who were significantly distanced from their partisan social identity, as measured by the party self index, by the self-affirmation treatment.Footnote 15

Thus, while we find robust evidence that both Democrats and Republicans internalize partisanship as a social identity, and that this attachment can significantly fluctuate with context and focus on personal identity, we do not find correspondingly strong evidence corroborating the claim that such attachments to partisan identity are what drive in-group favoritism or out-group animus.

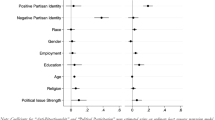

We turn now to the test of our final hypothesis, that the self-affirmation treatment effects would be strongest during times of political salience (i.e. in Wave 1). Figure 1 shows results consistent with our hypothesis. The self-affirmation treatment reduces Democrats’ internalization of partisan social identity in Wave 1, but not in Wave 2.Footnote 16 Figure 1 also shows that the self-affirmation treatment reduces Republicans’ attachment to their partisan identity in Wave 1 (significant at the 10% level in a one-sided test); there is once again no effect of the treatment in Wave 2. We interpret these findings as confirmatory of part one of Hypothesis 4. That is, we find significant evidence that those who are most attached to their partisan identities—both Democrats and Republicans in Wave 1—can be successfully detached from this identity during times of heightened political salience simply by focusing on their individuating characteristics.Footnote 17

Figure 1 also demonstrates once again a significant reduction in the extent to which both Democrats and Republicans internalized their partisan social identities from Wave 1 to Wave 2. Taken together with our self-affirmation treatment effects, and our previous presentation of our panel results in Table 4, we take this as strong evidence that partisanship, similar to other social identities, is subject to contextual flux. We also take these findings as further motivation for testing whether partisans exhibit increased in-group favoritism and out-group hostility during times of heightened identity salience (Tajfel and Turner 1979). In order to test this more precisely, we now turn to the results on our measures of affective polarization within Figs. 2 and 3.

Figures 2 and 3 once again show inconclusive or weak evidence that once subjects become relatively less attached to their partisan identities, they also become less likely to exhibit group-based bias.Footnote 18 That is, exposure to our self-affirmation treatment has no significant negative effect on either of our measures of affective polarization. This is true in both Waves 1 and 2, and is consistent with other recent null findings of the effect of self-affirmation on partisan affect (Levendusky 2018b). The independent wave effects (that is, the effect of going from Wave 1 to Wave 2 among subjects in the control condition) on our measures of affective polarization are also mixed. While there appears to be a negative wave effect on In-Out Party Thermometer among Republicans at the baseline, the standard errors are large. Moreover, this effect is small and once again insignificant (albeit still negative) among Democrats. And we once again find null wave effects on our measure of In-Out Party Supporter Traits among both Democrats and Republicans. Thus, we interpret these results as indicating that, while partisans’ attachment to their Democratic and Republican identities can fluctuate with political salience and with a focus on other aspects of the self, a weakened attachment does not necessarily translate into less group-based bias, the root of affective polarization. While this finding begs further investigation, the clear implication is that partisan social identity may not be the sole or even the principal driver of affective polarization in the United States. Put another way, we find evidence that the correlation between the expression of partisanship as key to the self-concept and the expression of negative affect toward the out-party may be confounded, since we have now shown that an exogenous shift in the former is not necessarily associated with a shift in the latter.

Conclusion

The standard explanation for affective polarization is that partisanship represents an important social identity. In this paper, we have documented that party affiliation is in fact an important ingredient of partisans’ self-concept. Moreover, the salience of partisan social identity fluctuates with context; Democrats and Republicans internalize their partisanship significantly more during times of heightened political salience. We also find that a heightened sense of identity threat increases the extent to which partisan identity contributes to individuals’ sense of self, although here our evidence is only suggestive. Taken together, our results provide important evidence that partisanship contributes to individuals’ self-concept, and that similar to other social identities, it is subject to significant transient fluctuation. Our findings suggest that it is important to consider factors that might lead to variation in the salience of partisan identity when attempting to measure partisan attitudes; for example, even question ordering within a survey’s flow might lead to important variation on measures associated with partisans’ internalization of their party identity.

As a second contribution, we use a self-affirmation treatment to show that individuals with the strongest sense of partisan social identity (i.e. Democrats, who likely experienced greater identity threat in advance of the 2018 midterm elections) become distanced from their social identity when they focus on individuating characteristics. We also find evidence for a similar negative effect of our self-affirmation treatment on the strength of partisan identity among Republicans in Wave 1, when political salience was higher due to an election. However, contrary to expectations, despite the fact that self-affirmation successfully pulled subjects away from their partisan social identity in Wave 1, and both Democrats and Republicans exhibited a weaker partisan self-concept in Wave 2, we do not find consistent evidence that a weakened sense of social identity necessarily leads to reduced affective polarization. That is, we find inconclusive evidence that either the difference in context or the self-affirmation treatment reduced the extent to which partisans were willing to elevate the in-group or denigrate the out-group, despite the fact that both induced significant reductions in attachment to partisan identity. Further, our evidence shows that the magnitude of the effects on our party self index are much larger relative to the size of our effects on two typical measures of affective polarization, in-out party feeling thermometers and an in-out party trait index.

Overall, we interpret these findings as strong evidence for the fact that partisanship is an important social identity. Yet, we could not demonstrate that a weakened sense of partisan social identity contributes strongly or consistently to reduced affective polarization. Detaching partisans from their social identity does not consistently make them any less likely to elevate their in-group and to denigrate their opponents. This evidence is consistent with other accounts of affective polarization, such as those that attribute the phenomenon to ideological polarization, strong intra-party alignment on key issues, social sorting, and the media (Bougher 2017; Abramowitz and Webster 2016; Lau et al. 2017; Lelkes 2019). Nonetheless, in light of extant literature suggesting that partisanship as a social identity leads to affective polarization, the inconclusive nature of our findings with respect to reductions in affective polarization is striking. We conclude here by suggesting further explorations of this disconnect between strength of group identity and group affect in order to reconcile these two camps of explanations.

First, while the variation in electoral context has a significant but small (by conventional standards) effect on partisan social identity, our self-affirmation treatment has an even weaker impact on partisans sense of social identity. Quite possibly, then, the detachment was insufficient to bring about the necessary change in partisan affect. Future research might experiment with stronger treatments to confirm that despite their weakened social identity, partisans remain sufficiently motivated to elevate the in-group and denigrate the out-group along party lines. Second, it is possible that our inability to find any reduction in affective polarization attributable to the weakened sense of partisan identity is due not to the weakness of our treatments, but rather to the possibility that in-party favoritism and out-party animus have been overlearned and are now operating implicitly. If this is the case, future research will need to pair treatments similar to those used here with implicit measures of partisan affect. Finally, it is possible that partisan animus stems not only from the dynamics of group identity, but also from non-identity related processes, such as ideological disagreement or observational learning from elite cues. Testing these and other possible alternative pathways to out-group animus would shore up the evidence provided here, which suggest that partisan animus is primarily driven by something other than attachment to partisan social identity.

Notes

To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to make these connections, which provide an alternative mechanism explaining self-affirmation’s effect on displays of in-group favoritism.

Nielsen ratings data show that viewership significantly drops off over the winter holiday season. For example, there is a 21% reduction in the viewership for MSNBC, and a 13% reduction for CNN from early December to the week of Christmas.

We requested a sample that was evenly distributed between Democrats and Republicans; while there were some Independents/non-partisans in our resulting sample, we exclude them from analysis given our focus on partisan identity.

We drop the 6 subjects who switched their party identification from Wave 1 to Wave 2. We take this as an indicator of either weak identification or, more likely, lack of attention, and thus, given our focus on partisanship, we exclude these observations.

Appendix Table 7 demonstrates that our self-affirmation treatment is in fact transient; that is, there are no significant differences in means on our primary outcomes in Wave 2 according to having been assigned to self-affirmation treatment in Wave 1.

We choose these alternative treatment and control conditions because they offer more experimental control than the canonical treatments, which involve an open-response writing exercise. The writing exercise also was not as conducive to the online format of our study.

A similar technique using celebrities instead of strangers in a photograph has been employed previously by Napper et al. (2009).

The manipulation check index is derived from seven questions asked in Wave 2 only, such as “How much did the previous exercise make you: ‘think about good things about myself’.

Results are substantively similar if the “values (no ranking)” (pure control) condition subjects are dropped from the analysis. See Appendix 6.3.

Both Wave 1 and Wave 2 implemented identical surveys. The general order of questions in both surveys was as follows: demographic / basic political questions (including partisanship and political interest); treatment screen; manipulation checks; affective polarization measures; partisan self questions (e.g. “Being a Democrat/Republican is an important part of my self-image.”).

See Appendix Table 7 for self-affirmation treatment assignment across waves without combining the pure control and treatment.

The replication data for this study can be found herehttps://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/OF2PIH.

While there is by random chance a significant difference between Democratic subjects’ ideology in treatment vs. control groups, this difference does not explain the significant treatment effect on the Partisan Self Index. Appendix Table 12 shows that treatment effects are substantively similar when controlling for ideology in a regression.

When we instrument Partisan Self with both wave and self-affirmation treatment assignment, we again find inconsistent evidence that a reduction in Partisan Self corresponds with a reduction in our measures of affective polarization. The results from these 2SLS analyses are in Appendix 6.9, and are similar to the results presented here; namely, while there is a wave effect on the feeling thermometer measure, the wave effects on the traits measure in our partisan subsamples is insignificant, and the self-affirmation treatment has null effects on both measures of affective polarization.

This effect is substantively similar in Appendix Fig. 11, which uses only true panel subjects. Recall that we focused on powering our self-affirmation treatment in Wave 1 given our hypotheses, and only powered our wave effects in Wave 2 by recontacting half of our initial respondents from Wave 1. Nonetheless, the self-affirmation treatment is still significant using the true panel, though the significance is reduced given these sample limitations.

Given the possibility of “testing effects” across waves, we replicate these findings in Appendix 6.8 dropping subjects who were treated in Wave 1 from the means calculated in Wave 2. Our results are substantively unchanged.

References

Abramowitz, A., & Webster, S. (2016). The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of U.S. elections in the 21st century. Electoral Studies, 41, 12–22.

Bankert, A. (2020). Negative and positive partisanship in the 2016 U.S. presidential elections. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09599-1.pdf.

Baumeister, R. F. (1999). Self-concept, self-esteem, and identity. In Nelson-Hall Series in Psychology (pp. 339–375). Personality: Contemporary Theory and Research. Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers.

Billig, M., & Tajfel, H. (1973). Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 3(1), 27–52.

Binning, K. R., Sherman, D. K., Cohen, G. L., & Heitland, K. (2010). Seeing the other side: Reducing political partisanship via self-affirmation in the 2008 presidential election. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 10(1), 276–292.

Bougher, L. D. (2017). The correlates of discord: Identity, issue alignment, and political hostility in polarized America. Political Behavior, 39, 731–762.

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 429–444.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chandra, K. (2012). Introduction and part one. In Constructivist theories of ethnic politics (pp. 385–403). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, G. L. (2012). Identity, ideology, and bias. In Identity, psychology and law (pp. 385–403). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, G. L., Bastardi, A., Sherman, D. K., Hsu, L., & McGoey, M. (2007). Briding the partisan divide: Self-affirmation reduces the ideological closed-mindedness and inflexibility in negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(3), 415–430.

Cohen, G. L., & Garcia, J. (2008). Identity, belonging, and achievement: A model, interventions and implications. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 365–369.

Cohen, G. L., Garcia, J., Apfel, N., & Master, A. (2006). Reducing the racial achievement gap: A social-psychological intervention. Science, 313(5791), 1307–1310.

Cohen, G. L., & Sherman, D. K. (2014). The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 333–371.

Cohen, G. L., Sherman, D. K., Nelson, L. D., Bunyan, D. P., David Nussbaum, A., & Garcia, J. (2009). Affirmed yet unaware: Exploring the role of awareness in the process of self-affirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(5), 745–764.

Devine, C. J. (2015). Ideological scoial identity: Psychological attachment to ideological in-groups as a political phenomenon and a behavioral influence. Political Behavior, 37(3), 509–535.

Druckman, J. N., & Levendusky, M. S. (2019). What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(1), 114–22.

Egan, P. Forthcoming. Identity as dependent variable: How Americans shift their identities to better align with their politics. American Journal of Political Science .

Fleisher, R., & Bond, J. R. (2001). Evidence of increasing polarization among ordinary citizens. In American political parties: Resurgence and decline. Washington: CQ Press.

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., Bachman, B. A., & Rust, M. C. (1993). The common ingroup identity model: Recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. European Review of Social Psychology, 4, 1–26.

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. London: Yale University Press.

Greene, S. (1999). Understanding party identification: A social identity approach. Political Psychology, 20(2), 393–403.

Hetherington, M. (2002). Resurgent mass partisanship: The role of elite polarization. American Political Science Review, 95, 619–31.

Hetherington, M. J., Long, M. T., & Rudolph, T. J. (2016). Revisiting the myth: New evidence of a polarized electorate. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 321–50.

Huber, G. A., & Malhotra, N. (2017). Political homophily in social relationships: Evidence from online dating behavior. The Journal of Politics, 79(1), 269–83.

Huddy, L. (2013). From group identity to political cohesion and commitment. In Oxford handbook of political psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17.

Iyengar, S., Konitzer, T., & Tedin, K. (2018). The home as a political fortress: Family agreement in an era of polarization. The Journal of Politics, 80(4), 1326–1338.

Iyengar, S., & Krupenkin, M. (2018). The strengthening of partisan affect. Political Psychology, 39(S1), 201–218.

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22, 129–146.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76, 405–31.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59, 690–707.

Klar, S. (2014). Partisanship in a social setting. American Journal of Political Science, 58(3), 687–704.

Klofstad, C. A., McDermott, R., & Hatemi, P. K. (2013). The dating preferences of liberals and conservatives. Political Behavior, 35(3), 519–538.

Kuhn, M. (1960). Self-attitudes by age, sex and professional training. Sociological Quarterly, 1, 39–56.

Lau, R. R., Andersen, D. J., Ditonto, T. M., Kleinberg, M. S., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2017). Effect of media environment diversity and advertising tone on information search, selective exposure, and affective polarization. Political Behavior, 39, 231–255.

Lelkes, Y. (2019). Policy over party: Comparing the effects of candidate ideology and party on affective polarization. Political Science Research and Methods. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.18.

Levendusky, M. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberals became democrats and conservatives became Republicans. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. S. (2018a). Americans, not partisans: Can priming American national identity reduce affective polarization? Journal of Politics, 80(1), 59–70.

Levendusky, M. S. (2018b). When efforts to depolarize the electorate fail. Public Opinion Quarterly, 82(3), 583–92.

Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1992). A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 302–318.

Mason, L. (2013). The rise of uncivil agreement: Issue versus behavioral polarization in the American electorate. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(1), 140–159.

Mason, L. (2015). “I disrespectfully agree”: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128–145.

Mason, L. (2018a). “I disrespectfully agree”: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 82(1), 866–887.

Mason, L. (2018b). Ideologues without issues: The polarizing consequences of ideological identities. Public Opinion Quarterly, 82(S1), 280–301.

Mason, L. (2018c). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McCarty, N., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2006). Polarized America: The dance of ideology and unequal riches. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

McQueen, A., & Klein, W. M. P. (2006). Experimental manipulations of self-affirmation: A systematic review. Self and Identity, 5(4), 289–354.

Michelitch, K., & Utych, S. (2018). How ideology fuels affective polarization. Journal of Politics, 80(2), 412–427.

Mutz, D. (2006). Hearing the other side: Deliberative versus participatory democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Napper, L., Harris, P. R., & Epton, T. (2009). Developing and testing a self-affirmation manipulation. Self and Identity, 8, 45–62.

Oakes, P. J., & Turner, J. C. (1980). Social categorization and intergroup behavior. European Journal of Social Psychology, 10, 295–301.

Onorato, R. S., & Turner, J. C. (2004). Fluidity in the self-concept: The shift from personal to social identity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34, 257–278.

Riek, B., Mania, E. W., & Gaertner, S. L. (2006). Intergroup threat and outgroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(4), 336–353.

Steele, C. (1999). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 261–302). Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers.

Steele, C. M., Spencer, S. J., & Aronson, J. (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 34, 379–440.

Sunstein, C. R. (2017). #Republic: Divided democracy in the age of social media. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Tajfel, H. (1970). Experiments in intergroup discrimination. Scientific American, 223, 96–102.

Tajfel, H. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. London: London Academic Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–66). Monterey: Brooks Cole.

Westwood, S. J., Iyengar, S., Walfrave, S., Leonisio, R., Miller, L., & Strijbis, O. (2017). The tie that divides: Cross-national evidence of the primacy of partyism. European Journal of Political Research, 57(2), 333–354.

Wood, J. V., Perunovic, W. Q. E., & Lee, J. W. (2009). Positive self-statements: Power for some, peril for others. Psychological Science, 20, 860–866.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Treatment Screens

Descriptive Statistics

In terms of its representativeness, our sample is about 73% white, which is on par with 2016 voter demographics—the CCS estimated white voters to have been roughly 74% of the 2016 electorate. The average age in our sample is about 49, which is roughly on par with 2016 voter age (where those 60 and older have by far the highest turnout rates—about 70%—followed closely by those age 45–59). The age and race demographics of our sample by party are also roughly on par with what we might expect given the growing numbers of non-white and younger voters within the Democratic party. Thus, while the extent to which our conclusions can be generalized to the U.S. voting population are reliant on the representativeness of our online convenience sample, the sample is not too far from this population on some key demographics.

Replication of All Main Results Dropping Pure Control Subjects

Wave Effects: Individual Traits (Not an Index)

See Table 10.

Wave Effects: Out-Party Traits Only

See Table 11.

Self-affirmation Results: Control for Ideology

See Table 12.

Interaction Effect Figures (True Panel Only)

Interaction Effect Figures: Drop W1 Subjects Who Received Treatment for Wave 2 (Make Sure Lack of SA Treatment Effect in W2 is Not Driven by “Testing Effects” from W1)

2SLS

SA Treatment Among True Panel Subjects is Transient

See Table 15.

Table 7 reports the means of each measure among samples in Wave 2 according to whether they were assigned to self-affirmation treatment or control in Wave 1.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

West, E.A., Iyengar, S. Partisanship as a Social Identity: Implications for Polarization. Polit Behav 44, 807–838 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09637-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09637-y