Abstract

There is no doubt that partisanship is a powerful influence on democratic political behavior. But there is also a lively debate on its nature and origins: Is it largely instrumental in nature and shaped by party performance and issues stances? Or is it basically a long-standing expressive identity reinforced by motivated reasoning and strong emotions? We assess the nature of partisanship in the European context, examining the measurement properties and predictive validity of a multi-item partisan identity scale included in national surveys conducted in the Netherlands, Sweden, and the U.K. Using a latent variable model, we show that an eight-item partisan identity scale provides greater information about partisan intensity than a standard single-item and has the same measurement properties across the three countries. In addition, the identity scale better predicts in-party voting and political participation than a measure of ideological intensity (based on both left–right self-placement and agreement with the party on key issues), providing support for an expressive approach to partisanship in several European democracies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Partisanship remains a powerful influence on political behavior within developed and developing democracies (Brader and Tucker 2009; Brader et al. 2013; Dalton and Weldon 2007; Green et al. 2002). In the United States, partisanship has increased in strength in recent years and continues to wield impressive influence on a range of political behavior including vote choice, voter turnout, and electoral campaign activity (Huddy et al. 2015; Nicholson 2012). Levels of partisanship have declined in a number of other developed democracies, (Dalton and Wattenberg 2002) but partisanship remains a potent political force nonetheless (Bartle and Bellucci 2014; Holmberg 1994).

If the influence of partisanship on political behavior is not in dispute, there remains a lively debate on its nature, origins, and by implication its measurement. Given the centrality of partisanship to the study of political behavior, lack of attention to its measurement is especially glaring. In this manuscript, we draw on social identity theory (Green et al. 2002; Huddy et al. 2015) to develop a multi-item measure of partisan identity and examine its measurement properties and predictive validity. In so doing, we provide support for the expressive approach to partisanship more generally. We develop the partisan identity scale for several multi-party systems in which there is a continuing debate over the nature of partisanship and its measurement (Johnston 2006; Thomassen 1976; Thomassen and Rosema 2009).

Instrumental and Expressive Partisanship

The extent to which partisanship reflects issue preferences, a reasoned and informed understanding of the parties’ positions, and is responsive to ongoing events and political leadership remains a central concern for normative democratic theorists. We refer to partisanship grounded in this type of responsive and informed deliberation as instrumental. As a test of instrumental partisanship, researchers have examined its origins in long standing socio-economic cleavages and contemporary forces such as issue proximity and leader evaluations (Dalton and Weldon 2007; Garzia 2013). Garzia (2013) reports, for example, that a mixture of social cleavages and leader evaluations have shaped partisanship in the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands with leader evaluations eclipsing the importance of social factors in recent decades. Researchers have also examined the degree to which partisans are aware of ideological shifts in a party’s platform with mixed results. Adams et al. (2011) find that the public remains unaware of a party’s changed platform whereas Fernandez-Vazquez (2014) reports a slight change in voters’ perceptions that falls far short of the magnitude of the actual change. Based on this accumulated research, partisanship appears somewhat responsive to certain contemporary forces such as changing leadership but much less so to shifting party positions, providing modest support at best to the instrumental model.

In the U.S, an alternative expressive identity approach to partisanship has gained credence. From this perspective, partisanship is a social identity that remains stable even as leaders and platforms change. Expressive partisanship involves motivated political reasoning in defense of the party, encourages the vilification of threatening out-parties, and leads to action-oriented emotions that result in heightened political activity. Most importantly, and at odds with an instrumental approach, these cumulative processes minimize strong partisans’ reactivity to accusations of poor party performance, weak leadership, or an altered platform resulting in a relatively stable political identity (Green et al. 2002). Moreover, partisan identity is likely to strengthen over time as a young voter consistently supports one party over others in successive elections (Dalton and Weldon 2007). The expressive approach to partisanship is grounded in social identity theory (Green et al. 2002; Huddy et al. 2015).Footnote 1

Social identity theory has been confirmed in numerous studies and the vast body of research that originated from it lends considerable insight into the dynamics of social and partisan identities (Huddy 2013). This research reveals that the effects of a social identity are most pronounced among strong identifiers, underscoring the need to reliably measure gradations in identity strength (Huddy 2001, 2013). In the United States, the expressive partisanship model has generated a new multi-item measure of partisan identity strength (Huddy et al. 2015). A similar scale is needed to assess partisan identity strength in multi-party systems which have suffered from inconsistencies in the measurement of partisanship (Johnston 2006).

Measuring Expressive Partisanship

Psychologists typically measure social identities with multiple items to create a fine-grained scale of identity strength. Several identity scales have been developed to assess partisan identity in the United States. Steven Greene (2002, 2004) used Mael and Tetrick’s (1992) Identification with a Psychological Group Scale to measure identification with one’s preferred party. The scale had good measurement properties and proved to be a better predictor than the standard partisanship measure of a range of political variables including political involvement. Huddy et al. (2015) developed a four-item scale with items that tap identity importance and sense of party belonging (see also Huddy and Khatib 2007). Both partisan identity scales include items designed to capture a subjective sense of group belonging, the affective importance of group membership, and the affective consequences of lowered group status, which are crucial social identity ingredients (Ellemers et al. 1999; Leach et al. 2008).

Multi-item partisan identity scales have proven to be more effective than the traditional single-item in predicting political outcomes such as political activity in the U.S. But there are reasons to question whether a partisan identity scale is needed and will be equally successful in predicting political outcomes in Europe. Partisan identity has been declining in Europe and may be more complex than in the U.S. because many European democracies operate as multi-party systems (Dalton and Wattenberg 2002; Huber et al. 2005). Moreover, multi-party systems often generate coalitional governments aligned along ideological lines that can also blur loyalty to a single party (Hagevi 2015; Meffert et al. 2009; González et al. 2008).

The development of a partisan identity scale also confronts several measurement hurdles in a multi-party European context. First, a good scale should identify partisans equally well at low and high levels of identification to accurately predict partisan behavior, such as campaign engagement and activity, across its range. Second, the scale should have the same measurement properties in different countries in order to identify equally well individuals with high and low levels of partisanship, regardless of nationality. Third, it should have predictive validity and better explain political activity than the traditional measure of partisanship or other issue-based measures that assess instrumental facets of partisanship.

Latent Trait Models: A Scale Assessment Tool

We regard partisanship as a latent construct that cannot be directly measured (for similar approaches, see Green et al. 2002; Green and Palmquist 1990). To gauge the properties of a partisan identity scale, we rely on latent trait models to test the ability of the partisan identity items to differentiate equally well across various levels of the latent trait, and establish that the scale has comparable measurement properties cross-nationally. We utilize Item Response Theory (IRT) for the first assessment and an invariance analysis for the second. We have specific predictions about the measurement properties of the partisan identity scale. Hence, we next provide a brief overview of our approach and terminology that are needed to develop our hypotheses.

Item Response Theory

We draw on IRT to analyze the measurement properties of a partisan identity scale. In essence, the IRT model determines the extent to which a response to a given scale item accurately reflects the underlying latent trait of partisan identity strength.

Due to the polytomous nature of our data (consisting of multiple ordered response options), we first apply the Graded Response Model (Samejima 1970), specifying “the probability of a person responding with category score \(x_{j}\) or higher versus responding on lower category scores” (De Ayala 2013: 218) to indicate higher values on the latent trait. The probability of agreeing with a response category or a higher response category on a given item j is based on both an individual’s score on the latent trait and the nature of the item used to assess the latent trait (see Allen and Yen 2001; De Ayala 2013). More formally, this cumulative probability can be expressed as:

where θ is the latent trait, \(\alpha_{j}\) is the discrimination parameter for item j, and \(\delta_{{x_{j} }}\) is the category boundary location for category score \(x_{j}\).Footnote 2 The item discrimination parameter indicates how strongly related the item is to the latent trait whereas the category boundary location can be viewed as the boundary between two adjacent response categories k and k − 1 (for a more detailed discussion, see De Ayala 2013). To obtain the probability of responding in a particular category k (i.e., the option response function), we calculate \(p_{k}\), which is the difference between the cumulative probabilities for adjacent response categories. It can be stated as:

Note that \(P_{k}\) is \(P_{{x_{j} }}\) from the previous equation. This change in notation arises because we use lowercase “p” to indicate the probability of responding to a particular category, and uppercase “P” to refer to the cumulative probabilities discussed earlier.

The probability of agreeing with a certain response category is a function of the latent trait \(\theta\) and can be plotted for each response option, graphing the underlying latent trait on the x axis and the probability of picking that option on the y axis. Typically, all functions of an item’s response options are plotted on the same graph to indicate the relationship between the latent trait and the probability of choosing a certain response category.

Subsequently, we plot the item information function (IIF), which represents the information provided by a specific item x, across the range of the latent trait. With polytomous data, it is also possible to first determine the amount of information provided by each response category. Formally, the category information function for graded responses (Samejima 1970) is expressed as:

where θ denotes the latent trait, x j refers to the response category j of the ordinal manifest variable x and p k refers to the probability of an individual picking a particular response category. The sum of these option information functions equals an item’s overall information (IIF) and is defined as:

Graphing the item information function illustrates an item’s difficulty (i.e., location on the latent trait continuum) as well as an item’s discrimination (i.e., the item’s information) in measuring the underlying latent trait. Hence, the item information function identifies items that are good at detecting high but not low, low but not high, and middling levels of the trait as well as their ability to do so reliably. In essence, a peak in an item’s information function indicates that a specific level of the underlying trait is captured with high precision. From that vantage point, an ideal scale entails items with narrowly peaked item information functions at locations across the latent trait’s range to construct a scale that is highly discriminating and provides considerable information about the trait overall (De Ayala 2013).

Last, the individual item information functions can be further summed to generate an information function for the entire scale, indicating how well it discriminates among values of the latent trait:

Invariance Analysis

To test the scale’s invariance, we employ a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to determine if the underlying latent trait is measured in the same way across countries. Invariance is defined here as “whether or not, under different conditions of observing and studying phenomena, measurement operations yield measures of the same attribute” (Horn and McArdle 1992, p. 117). Measurement invariance is established by comparing the fit of a series of hierarchical CFA models with increasingly stringent equality constraints (Cheung and Rensvold 1999; Vandenberg and Lance 2000).

The most basic type of invariance, configural invariance, is established if the same items load on the same factor across countries. Put differently, configural variance ensures that items measure the same construct in all countries. Once configural invariance is established, the next most stringent form of invariance is metric invariance which assumes that all items load on the same factor (as in configural) and their loadings are constrained to be equal across countries. Metric invariance is established if the metric invariance model is no worse a fit to the data than the baseline model that establishes configural invariance (Asparouhov and Muthén 2014; Hirschfeld and von Brachel 2014). Evidence for metric invariance indicates “…that the people in different nations understand the items in the same way” (Davidov 2009, p. 69). While metric invariance allows researchers to compare analytic models across countries, it does not guarantee that observed differences in the mean levels of the scale reflect differences in the mean levels of the underlying latent trait. Thus, the final step in a hierarchical invariance analysis involves testing for scalar invariance. In this model, factor loadings and the intercepts are constrained to be equal. If the fit of the scalar variance model is not significantly worse than the fit of the metric invariance model, there is evidence that the scale’s scores can be compared across countries.

Hypotheses

We test three hypotheses concerning the validity of a partisan identity scale with data drawn from national surveys conducted in the Netherlands, Sweden, and the U.K. First, to serve as a standardized measure of partisanship, the partisan identity scale should differentiate equally well among low, middling, and high levels of identity to best uncover the link between identity and political activity across its full range. We expect each scale item to provide more complete information about partisan strength than the traditional single party identification item. In terms of the IRT analysis, this means that each item’s information function will be more peaked and contain greater information than the standard single measure of partisan strength. In the three European multi-party systems under study, we expect both lower and higher levels of partisan intensity to remain less well detected when measured with the traditional item.

Second, the partisan identity scale should have the same meaning and properties across countries even when such countries exhibit different levels of partisanship. To test this, we examine the scale’s configural, metric, and scalar invariance. We expect the partisan identity scale to exhibit all three types of invariance, which means that the fit of the metric invariance model will be no worse than the fit of the configural model, and that the fit of the scalar model will be no worse than that of the metric model.

Third, we test the partisan identity scale’s predictive validity. We expect partisan identity to more powerfully predict in-party voting and political engagement than the traditional party identification item. We also expect the partisan identity scale to better predict political behavior than a multi-item indicator of ideological intensity. If successful, this last test helps to rule out the possibility that the identity scale has greater predictive validity than the traditional single-item because of its better measurement properties.

Methodology

Sample

Netherlands

We employ data collected before and after the 2012 Dutch Parliamentary elections among members of the Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences (LISS) panel. The LISS contains 5000 households, entailing 8000 individuals, drawn as a true probability sample of households in the national population register maintained by Statistics Netherlands. Non-computer households are provided with a computer and internet connection and the panel members complete monthly online surveys and receive payment for each completed questionnaire. Data are drawn from three time points: August 2012 (“Elections 2012”), after the national election in September 2012 (“Dutch Parliamentary Election Study”), and again as part of a module in December 2012/January 2013 (“Politics and Values: Wave 6”).Footnote 3 We examine the measurement properties of the partisan identity scale among 4680 respondents who were identified as having a partisan preference and completed the identity items in the pre-election module. Predictive validity analyses are conducted on a smaller set of respondents (N = 4263) who completed surveys at all three time points.

Sweden

Swedish data were drawn from the Swedish Citizen Panel, a largely opt-in online panel run by the Laboratory of Opinion Research (LORE) at the University of Gothenburg. We utilize data from Panel 8 (11/14/13–12/18/13) and add-on Panel 8-2 (12/10/13–1/7/14). 16,130 panelists were invited to take the Panel 8 survey and 9279 completed it for a completion rate of 64 %. 2000 panelists were invited to complete Panel 8-2 of which 1496 answered the survey. All panelists in Panel 8.2 and a randomly selected 2000 panelists in Citizen Panel 8 received the identity model. Our analytic sample is confined to those in Panel 8 and Panel 8-2 who completed the identity items (N = 2464).Footnote 4

United Kingdom

Data for the U.K were taken from the 2015 British Election Study (BES), an online panel study conducted by YouGov.Footnote 5 We draw on data from pre-election wave 3 of the BES, conducted between September 19, 2014 and October 17, 2014 and pre-election wave 4, conducted in March 2015. In total, 27,839 respondents participated in wave 3 and 6141 were randomly assigned and 5954 completed a module that included the partisan identity items. In wave 4, 16,629 respondents participated and 3500 of them completed the partisan identity module. The more numerous data from wave 3 are used to examine the measurement properties of the partisan identity scale in the U.K. and data from wave 4, which includes key political dependent variables, are used to assess its predictive validity.

Measures

Partisanship Strength

The partisanship question was asked differently in each of the three countries, underscoring the lack of uniformity in its assessment. In the Netherlands, respondents in the pre-election survey were first asked if they thought of themselves as an adherent of a political party, if so which party, and whether they would call themselves a very convinced adherent, convinced adherent, or not so convinced adherent. If they did not think of themselves as an adherent, they were asked if they were more strongly attracted to one party, if yes to which party and how strongly (very strongly, fairly strongly, not so strongly). If they were not attracted to a party, they were asked what party they had voted for in the last election in order to assess partisan identity among as large a sample as possible. In Sweden, respondents were asked if they felt close to a particular political party. If they named a party, they were then asked if they felt very close, rather close, or not very close. U.K. respondents were asked “Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrat or what?” If no party was provided, respondents were asked “Do you generally think of yourself as a little closer to one of the parties than the others? If yes, which party?” Respondents who listed a party in response to either question were then asked “Would you call yourself very strong, fairly strong, or not very strong [partisan]?” The partisan strength item thus had at least three categories in each country.

Sizable numbers of respondents were partisans, even if weakly so. In the Netherlands, 90 % of respondents indicated a preference for a party (adherents, attracted, had voted for a party in the last election); 61 % reported adherence or attraction to a party. In Sweden, 91 % indicated that they were close to a party, and 86 % of those in the U.K. indicated a party preference.Footnote 6 Differences in wording make it difficult to compare partisan strength with this measure, however. We created a three-item measure in Sweden and the U.K. as seen in Table 1. A majority or near-majority placed themselves in the middle of the strength scale.

In the Netherlands, we also created a three-level partisanship measure (adherent, not an adherent but attracted to a party, neither adherent nor attracted but had voted for the party in the last election). When constructed in this way, the number of supporters in the Netherlands is comparable to those who said they were very close or strong partisans in Sweden and the U.K. From this three-level measure, we created a 0–1 measure of partisan strength with 1 representing the strongest partisan.Footnote 7

The inclusion of the non-partisan group in the Netherlands is unorthodox, however. As a check we re-ran all analyses in this paper excluding those who were not traditional partisans (i.e., neither adhered nor were attracted to a party). This did not alter any of the substantive results reported in this manuscript.

Partisan Identity Strength

The partisan identity scale is based on the Identification with a Psychological Group (IDPG) scale created by Mael and Tetrick (1992). We adapted five items from the original scale, and added three new items for inclusion in national surveys in the U.K., Sweden, and the Netherlands.Footnote 8 Unfortunately, the response options differ between the U.K. (“agree-disagree”) and the Netherlands and Sweden (frequency) but this does not undermine the scale’s comparability across nations as we show subsequently. Table 2 provides wording and responses to all 8 partisan identity questions in each of the three countries (for wording in Dutch and Swedish see Table A1, Online Appendix). The partisan identity items were asked of respondents who had indicated a party preference in response to the partisanship question. This resulted in 4680 complete responses in the Netherlands, and 2464 in Sweden.Footnote 9 In the BES, a randomly selected 25 % of those with a party preference were asked and 5954 completed the partisan identity battery in wave 3 and 24 % of respondents with a party preference were randomly assigned to the partisan identity module in wave 4 resulting in an effective sample of 3500 respondents.Footnote 10

The partisan identity questions elicit considerable variance across countries as can be seen in Table 2. Partisan strength is highest in the U.K., followed by Sweden, and then the Netherlands. For example, when asked if they say ‘we’ rather than ‘they’ when talking about their party, only 25 % of those in the BES strongly disagree whereas 80 % of the Dutch and 65 % of Swedes say they never feel this way. When asked if they feel connected with someone who supports their party, 57 % of wave 3 BES respondents agree; 27 % of Swedes and 16 % of the Dutch say they feel this way always or often. We created an additive partisan identity scale from these eight items. The scale ranges from 0 to 1 with 0 representing no party identity and 1 representing the strongest identity.

The Partisan Identity Scale

Scale Measurement Properties (IRT)

Since each item in the partisan identity scale contains four response categories (e.g., rarely/never, sometimes, often, and always in the Netherlands and Sweden), we apply a Non- Rasch Model for ordered polytomous data, namely the Graded Response Model (Samejima 1974).Footnote 11 Based on the information provided by each item’s response categories, we generated an information function for each item and then for the scale as a whole for each country. Figure 1 contains the graphical representation of each item information function by country. Graphs were created using the ltm package (Rizopoulos 2006) in R (see Figs. A1, A2, and A3 in the Online Appendix for each item’s option response function, and Figs. A4, A5, and A6 for the overall scale information function in each country).

Dichotomous items tend to generate unimodal item information functions in IRT but polytomous items, as in this scale, tend to have multiple peaks, as seen in Fig. 1. The multiple peaks occur because adjacent option information functions for a specific item are combined to form an overall item information curve whereby the peaks represent the location on the underlying partisan identity trait at which an item provides the greatest amount of information. Information is defined as the reciprocal of the standard error of measurement (i.e. the variance of the latent trait level) at a given point on the latent trait. Put differently, the amount of information in Fig. 1 is an indicator of an item’s ability to measure reliably a certain range of the latent trait. Thus, more information means less error.

In Fig. 1, latent partisan identity strength is arrayed on the x-axis and has, in its transformed scale of theta, a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 with a somewhat arbitrary range that covers the full range of the latent trait.Footnote 12 In our case, the theta for partisan identity can range from −4 to 4, with those closer to −4 displaying lower levels of partisan identity strength and those closer to 4 displaying higher levels of partisan identity strength. Thus, an information function that peaks closer to 4 provides a considerable amount of information at high levels of partisan identity strength whereas an information function that peaks closer to −4 better captures lower levels of partisan identity strength. Finally, an information function that peaks in the midpoint of the latent trait suggests an item with considerable ability to distinguish middling from higher and lower levels of identity strength.

While the amount of information provided by an item represents its ability to differentiate between partisans of different strength, the distance between each peak is suggestive of the range of partisan identity strength that is covered by an item. If the distance between two adjacent peaks is large, the item provides less information about levels of partisan identity in between peaks. When the distance is smaller and the peaks are located more closely together on the latent trait continuum, the loss of information becomes less severe. Thus, ideal items should cover a wide range of partisan identity strength and be able to discriminate effectively among different levels. To compare the information provided by each item in the partisan identity scale with the traditional three-point strength measure, we added the item information function for the latter to each figure. Figure 1, Panels A, B, and C depict the item information function for all eight scale items and the traditional strength measure in The Netherlands, Sweden, and U.K. respectively.

Our first hypothesis concerns the ability of the items in the partisan identity scale to provide more information than the single traditional measure of latent partisan strength across its range. Figure 1 demonstrates that the eight items supplement each other to cover a broad range of the underlying partisan identity trait in each country. The individual items vary in amount of information as well as in their ability to capture high or low levels of partisan identity.

In all three countries, two items display multiple peaks below the midpoint of the latent trait continuum and thus, provide especially good coverage of lower levels of partisan identity: “When I meet someone who supports this party, I feel connected”, indicated in purple, and “When people praise this party it makes me feel good” indicated in black. A third item, “I have a lot in common with other supporters of this party,” indicated in dark blue, also provides reasonable information at lower levels of partisan identity. In contrast, the item “When I speak about them, I refer to them as my party” provides good coverage of higher levels of partisan identity in all three countries.

Combining these items into a scale helps to compensate for weaknesses in any one item. For example, there is a large gap in the U.K. (Panel C, Fig. 1) between 0 and 1 on the partisan identity strength continuum for the item “When I meet someone who supports this party, I feel connected.” This gap is covered, however, by the item “When I speak about this party, I refer to them as ‘my party’”. The remaining four items in the scale vary in the amount of information they provide about partisan identity. The item “I am interested in what other people think about this party” (red line) is by far the weakest, providing little information and failing to discriminate among those at low, middling or high levels of partisan identity. Thus, the combination of several items provides the scale with the ability to cover a broad range of party identification levels while effectively differentiating among them.

In support of our hypothesis, the information function for the weakest of the 8 items (“I am interested…”) looks similar to the information function for the traditional partisan strength measure, depicted as a broken black line in Fig. 1. This demonstrates that the simple three-point measure provides little information and poorly discriminates across the range of the latent partisan identity trait. In the Netherlands (Panel A), the traditional strength measure is characterized by a wide bell curve ranging from -2 to 2 on the latent trait continuum. This shape suggests that the measure captures party identification strength at both the low and high end respectively but that it does not provide a great deal of information relative to the scale items. Partisan strength performs a little better in Sweden (Panel B) but provides similarly modest information in the U.K.—as shown in Panel C. The single strength item performs best in Sweden where it provides additional information on both sides of 0, suggesting that it does discriminate between weak and strong partisans to a greater degree than in the Netherlands or the U.K. Overall, the partisan identity scale measures partisan identity well across its range, a distinction that is captured far more poorly by the traditional single-item of partisan strength.Footnote 13

Cross-National Partisan Identity Scale Invariance

We next consider the partisan identity scale’s cross-national properties in a test of our second hypothesis, beginning with the scale’s configural invariance. Scale invariance is tested in a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the lavaan package in R.Footnote 14 Lavaan provides several fit measures that are widely used in measurement invariance analyses (see Coenders and Scheepers 2003; Davidov 2009; Pérez and Hetherington 2014) including the χ 2 statistic, the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Gamma-Hat and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) which we present for each invariance model in Table 3.

The fit indices for the configural invariance model in the first row of Table 3 indicate a good model fit. The TLI, and CFI are above the cutoff value of 0.95 (Hu and Bentler 1999) and the RMSEA value is below 0.05, a threshold commonly used to determine model fit (Kenny et al. 2014; Browne and Cudeck 1993). The χ 2 statistic is relatively high given the degrees of freedom but in contrast to other fit indices the test is more sensitive to overall sample size, differences in sample sizes between groups, non-normality, and model complexity (e.g. Hu and Bentler 1999, 1998; Bentler and Bonnet 1980). Hence, we rely on the alternative fit indices to evaluate the model performance. From this vantage point, we cannot reject the configural model and conclude that the partisan identity scale measures the same construct in the Swedish, Dutch, and British sample with all items loading on one factor in each country.

The fit indices for metric invariance are presented in the second row of Table 3. In this somewhat more stringent model, factor loadings for all items are constrained to be equal across countries. Once again, we cannot reject the metric invariance model because it does not lower fit indices when compared to the configural model (e.g. ΔCFI = 0.001; ΔTLI = 0.001). In fact, the RMSEA increases by as little as 0.003 and the Gamma-Hat remains constant. The χ 2 difference again indicates a significant increase in this model (p < 0.05) but, as noted, large sample sizes can generate large χ 2 differences (Cheung and Rensvold 2002; Davidov 2009). Table 4 summarizes the invariant factor loadings for the Dutch, Swedish, and British samples. All factor loadings are substantial and significant. These results suggest that the partisan identity scale has the same metric across countries. In other words, a unit increase in the partisan identity scale means the same thing in the Netherlands, Sweden, and the U.K.

Finally, we test the most stringent model: scalar invariance. In this CFA model, the intercepts of the eight scale items are constrained to be equal across countries (in addition to prior constraints placed on the factor loadings). This model tests whether a given observed value of the partisan identity scale indicates the same level of the latent partisan identity trait in each country. In other words, if the scale is arrayed from 0 to 1, zero would mean the complete absence of identity, 0.5 would indicate the same level of middling identity, and 1 would indicate maximum identity strength across countries. Fit indices presented in Table 3 provide mixed evidence on this point. The CFI, TFI, and the Gamma-Hat values indicate a good fit. The RMSEA value, however, is above the cutoff point of 0.05.Footnote 15

It is difficult to advocate cross-national use of the partisan identity scale in the absence of scalar invariance so we turn to an alternative test. Following Oberski (2014), we examine invariance sensitivity, “…the likely impact of measurement differences on substantive comparisons of interest” (Oberski 2014, p. 3). Sensitivity analyses are used to supplement the results of traditional invariance tests which often rely on arbitrary cutoff lines (for a thorough critique of cutoff values for fit measures, see Barrett 2007). We compute the EPC-interest which is a measure of the expected change in the parameter of interest, partisan identity in this case, when freeing a particular equality constraint. With the EPC-interest we can evaluate whether it is feasible to compare partisan identity means across countries by estimating the change in partisan identity if certain invariance restrictions (such as equivalence constraints on a scale item’s intercept) are removed. Put differently, the EPC-interest evaluates directly whether a violation of measurement invariance also leads to biased estimates of partisan identity in different countries (Oberski 2014).

In the previous invariance analyses, RMSEA was above the cutoff point indicating that the scalar invariance model was a poor fit to the data. Table 5 shows the EPC-interest values that exceeded 0.05 when the scalar invariance restrictions of equal factor loadings and intercepts are relaxed. As can be seen in Table 5, very few items shift in terms of the mean value of the latent partisan identity trait. Overall, dropping the equivalence restrictions on item 1 (“When I talk about this party, I say ‘we’ instead of ‘they’”) in the U.K. and Sweden increases very slightly the mean value of latent partisan identity in the Netherlands and the U.K. Dropping the equivalence restrictions for item 8 (“When people praise this party, it makes me feel good.”) decreases the latent partisan identity score slightly in the U.K. and the Netherlands. Overall, these changes are minor in magnitude with any given EPC-interest at or below 0.076 in absolute value. This number is significantly smaller than the latent mean differences of partisan identity across countries which are much larger (the absolute difference between the U.K and Netherlands is 0.133, the U.K. and Sweden is 0.645, and the Netherlands and Sweden is 0.512).Footnote 16 The minor influence on the latent party identity trait scores indicates that our substantive conclusions regarding the comparison of partisan identity across countries are not changed to any great degree by potential model misspecifications. Even when the requirements of the scalar invariance model are relaxed the magnitude of partisan identity remains relatively constant. Overall, these results provide evidence for our claim that the partisan identity scale exhibits features of scalar invariance and works similarly in all three countries.

Partisan Identity and Political Behavior

Our third hypothesis is that partisan identity better predicts political behavior than the traditional measure of partisanship strength or a multi-item scale of ideological intensity. To determine the identity scale’s predictive validity, we examine its effect on in-party voting, and political participation, combining data from all three countries.

Measures

In-Party Voting

In-party vote was coded 1 for those who indicated that they would or had voted for their party. In the Netherlands this was assessed after the 2012 election. In Sweden, respondents were asked if they intended to vote for their party in the following year’s election. And in the U.K. respondents were asked who they would vote for “if there were a U.K. General Election tomorrow.” In-party voting was highest in Sweden (88 %), intermediate in the U.K. (76 %),Footnote 17 and lowest in the Netherlands (61 %).

Political Participation

A scale of political participation was created for each country. In the Netherlands, the scale ranged from 0 to 4 activities (involved in party, attended meeting, contacted a politician, participated online) engaged in over the past 5 years, as measured in the post-election Politics and Values module. In Sweden, 915 Swedish respondents were randomly assigned to answer four questions on whether they had ever contacted a politician, contacted a civil servant, given money, or attended a rally. In the U.K., the activity scale was made up of responses to 13 questions asked in wave 4 about exposure to various online sources of campaign information. All 13 questions were combined additively and rescaled on a 0 to 1 scale. These questions clearly reflect a heterogeneous set of activities and time frames. Data from all three countries are combined in the following analysis and dummy variables for country are included as a control for differences in the nature and time frame of political participation.Footnote 18

Ideological Intensity

We constructed an ideological intensity scale to measure the respondent’s ideological strength and alignment with the in-party. In the U.K., agreement with 5 left–right values were combined on a −0.5 to +0.5 scale, with −0.5 representing the most right-leaning position and 0.5 representing the most left-leaning position. The scale was then folded around 0. Respondents whose overall score was at odds with their party preference were given a score of 0. In Sweden, the ideological intensity scale was created in the same way from five issues, including the reduction of the public sector, lowering taxes, and increasing unemployment benefits. The Dutch survey excluded a multi-item ideological scale and ideological intensity was measured by the respondent’s self-placement on a left–right dimension. Those whose left–right placement conflicted with that of their party received a score of 0. Ideological intensity was modest in all three countries and only weakly related to partisan identity (see Table A4, Online Appendix).

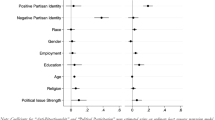

Determinants of In-Party Voting

The third hypothesis predicts stronger effects of partisan identity than traditional partisanship strength or ideological intensity on political behavior. We analyse the determinants of in-party voting using a logistic regression model. The results are shown in Table 6. Similar results are obtained when the data are analysed within each country (Table A5, Online Appendix). The first column in Table 6 estimates an equation in which in-party voting is regressed on partisan identity; the second column contains the same analysis replacing partisan identity with the single-item measure of partisanship strength, and the third column estimates an equation which includes both variables. Both partisan identity and the traditional strength measure significantly increase the likelihood of voting for one’s party when entered separately and together, as seen in columns 1 to 3.

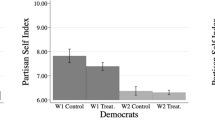

The magnitude of these effects can be seen in Fig. 2 which plots the predicted values of in-party voting across the range of partisan identity strength and traditional partisanship strength for each country, holding all other variables in columns 1 and 2 of Table 6 at their mean. Partisan identity strength has a sizeable influence on in-party voting and its effects exceed that of partisanship strength. The probability of voting for one’s party ranges from a low of roughly 0.45 in the Netherlands and 0.5 in the U.K. at the lowest levels of partisan identity to a high of 0.9 for those at the highest levels. In contrast, the probability of in-party voting changes less dramatically across the range of partisanship strength, ranging from a low of 0.4 to a high of 0.75 across the range of strength in the Netherlands, and just under 0.6 to above 0.8 in the U.K. The effect of both partisanship and identity strength on in-party voting is reduced in Sweden where partisan loyalty was high across the board, as seen in the top panel of Fig. 2. There is one other noteworthy aspect of the trends depicted in Fig. 2: Voting for one’s party increases rapidly at lower levels of partisan identity and tends to decelerate at higher levels. This trend is less apparent for partisanship strength.

Holding a strong ideological position that is consistent with one’s party also significantly increases in-party voting, as seen in Column 1 of Table 6, although this effect evaporates in column 2 when paired in the equation with partisan strength. The effects of ideological intensity are also far weaker than those of partisan identity strength: The probability of in-party voting changes from 0.75 (0.01) to 0.78 (0.01) across the range of ideological intensity, although this range is higher in the Netherlands (0.47 to 0.7). These effects are far weaker than those observed for partisan identity strength.

As a further test of the instrumental model, we re-ran the models in columns 1 and 2 of Table 6 for in-party vote in the U.K. replacing ideological intensity with in-party leader evaluations.Footnote 19 Results are shown in Table A6 in the Appendix. In-party leader evaluations are a stronger predictor of in-party vote than partisan identity strength although partisan identity continues to significantly increase in-party vote. Partisan identity strength and in-party leader evaluations are strongly correlated (0.42), however, complicating this comparison. In contrast, leader evaluations are virtually uncorrelated with ideological intensity suggesting that they may be more a function of expressive than instrumental partisanship, something we cannot easily resolve in this study.

Determinants of Political Participation

The analysis of political participation unfolds in parallel to that of in-party voting. As seen in columns 4, 5, and 6 of Table 6, both partisan identity and partisanship strength are significant predictors of political engagement, although the effects of partisan identity are roughly twice as large as those of partisanship strength when entered into separate equations, and over four times as large when both are entered simultaneously. Predicted levels of participation across the range of party identity and partisanship strength (based on equations in columns 4 and 5) are shown in Fig. 3. The effects of party identity and partisanship strength also differ by country. Partisan identity has greater influence on participation in Sweden, indicated by a positive interaction between Sweden and party identity, and lesser influence in the Netherlands, reflected in a negative interaction, as seen in column 4 of Table 6.Footnote 20 Similar interactions exist between the two countries and partisanship strength. In Sweden, participation ranges from 0.37 at the lowest level of partisan identity to 0.75 at the highest (Fig. 3). In contrast, the effects of partisanship strength are more muted (ranging from 0.36 to 0.57 across the range of partisanship strength). Figure 3 also makes clear that the differing time frames within which political activity was assessed (“ever” in Sweden compared to shorter time frames in the U.K. and Netherlands) affected mean levels of reported activity.

Ideological intensity has a small significant effect on political participation although its coefficient (0.07 in column 6) is far smaller than the coefficient for partisan identity (0.23 in this equation). As noted, ideological intensity is better measured by multi-item issue/value scales in the U.K. and Sweden than in the Netherlands where it was based on a single self-placement left–right intensity measure. This may have led to an underestimation of the effects of ideological intensity in the combined analyses shown in Table 6. When the analyses in Table 6 are repeated for reach country (Table A5, Online Appendix), the effects of ideological intensity are far smaller in the Netherlands than in Sweden or the U.K. Nonetheless, the coefficient for partisan identity is eight times the size of that for ideological intensity in the Netherlands, twice as large in Sweden and 3.5 times as large in the U.K. (Table A5). These findings provide support for both the expressive and instrumental models of partisanship, although the expressive model gains greater support in analyses of political activity. As a further test of the instrumental model, we re-ran the equations in columns 4 and 5 of Table 6 in the U.K. replacing ideological intensity with in-party leader evaluations and find that leader evaluations are a far weaker predictor than the partisan identity scale of political participation (see Table A6, Online Appendix). This provides further support for the expressive partisanship model.

Finally, to underscore the additional predictive power of the partisan identity measure over standard partisanship strength, we regressed in-party voting and participation on partisan identity, country, the interaction between country and partisan identity, and basic demographics at each level of partisanship strength (i.e., “not so strong”, “fairly strong” and “very strong”). Partisan identity predicted in-party vote and participation while holding partisan strength constant (analyses shown in Table A7 in the Online Appendix). Among weak, moderate, and strong partisans, partisan identity has a significant additional effect on in-party voting and political participation.

Four-Item Partisan Identity Scale

Many surveys have space limitations and therefore lack sufficient space for an eight-item scale. We examined a shorter four-item scale that performed especially well in differentiating across the range of partisan identity. The four items were chosen based on the information they conveyed about partisan identity in the IRT analyses. We re-ran all analyses presented in this manuscript with the shorter scale comprised of these items (marked with an asterisk in Table 2). These results are shown in Tables A8 and A9 (Online Appendix) and confirm the predictive power of partisan identity when measured with a shorter four-item scale. The short scale attains results very similar to those shown in Table 6.

Conclusion and Discussion

In this paper, we revisit the measurement and conception of partisanship, examining the properties of a multi-item scale of partisan identity in three European nations. While Greene (1999, 2002, 2004) and others (Green et al. 2002; Huddy et al. 2015) have argued for a multi-item approach to the measurement of partisanship, most national election studies continue to rely on a single measure. The ability of the partisan identity scale to differentiate weak, middling, and strong levels of partisanship provides a good reason for its inclusion in political behavior research. Its greater predictive validity, especially in accounting for political participation but also in-party voting, provides an even more powerful rationale for the broad adoption of a multi-item partisan identity scale.

To implement the partisan identity scale, a stem question is needed to identify a chosen party. National election studies participating in the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) include the following question: “Do you usually think of yourself as close to any particular party?” This is a good way to identify partisan direction and can be followed by the 4 or 8 identity strength questions discussed in this manuscript. In most countries that participate in the CSES, the question garners a majority of respondents who feel at least closer to one party than another, although there are a few countries in which this does not occur. The use of the CSES stem question would avoid a potential problem in the current study in which the base partisan question was cognitive in the U.K. (“think”) and affective in Sweden (“feel closer”). In the U.S., there is conflicting evidence on whether or not this wording makes a difference. Burden and Klfostad (2005) find that it does and regard the “feel” question as a more accurate measure of partisanship whereas Neely (2007) finds it makes no difference. At a minimum, it is important to ask the same stem partisanship question across contexts to standardize the measurement of partisan identity.

In the current research, party affiliation was especially low in the Netherlands where respondents were asked about being a party adherent, attracted to a party, or having voted for a party in order to obtain a respondent’s party affiliation. But even in the Netherlands, 70 % of the electorate has a party affiliation when assessed with the CSES questions. The social identity approach to partisanship holds considerable potential for the study of comparative politics more broadly. In the U.S., a similar partisan identity scale predicts political behavior in a political system that is dominated by two parties and characterized by strong levels of partisanship (Huddy et al. 2015). In the three European countries studied in this research, the partisan identity scale predicted political behavior despite varied levels of partisan strength and number of political parties. We have focused to a considerable degree in this research on the promising measurement properties of the partisan identity scale. But the study also hints at its conceptual heft. Partisan identity was a far better predictor of political behavior than a measure of ideological intensity, at odds with an instrumental model of partisanship. Partisan identity was also an especially good predictor of political activity in support of the expressive approach.

Our findings also raise a number of broader considerations for the study of European partisanship and elections. Levels of partisanship have declined in Europe in recent decades, in part because weak but not strong identifiers have abandoned their parties (Dalton and Wattenberg 2002). And this decline in partisanship has led to greater electoral volatility, an increase in personality-centered elections, and heightened economic voting (Dalton and Wattenberg 2002; Kayser and Wlezien 2011). Perhaps more importantly, our finding and theoretical framework suggest that inadequate measurement of partisan identities in European surveys has led to the underestimation of the link between partisanship and political activity. This is a serious omission that raises an additional set of questions about the political fallout of declining partisanship. We believe that our measure of partisan identity provides a useful instrument with which to observe changes in levels of partisan affiliation over time and track the consequences of theses shifts within European polities.

Multi-party systems also raise questions about several other aspects of partisanship. Are party identities positive or can they be negative in nature, so that an identity rests on not identifying with a specific party? Garry (2007), for example, utilizes an affective measure to account for multiple and negative party attachments in Northern Ireland. Medeiros and Noël (2013) demonstrate the predictive power of negative partisanship in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. It is possible to adapt the current approach to the assessment of a negative identity by modifying items to refer to the party with which one does not identify (e.g., “When people criticize X, it makes me feel good”). Another central question is whether citizens identify with a larger coalition of parties or with a single party within a coalition. Hagevi (2015) examined this in Sweden, measuring identification with a single political bloc and found additional effects of bloc identification on vote choice. This approach could be expanded to develop a multi-item identity scale with a political coalition and a specific party to contrast their relative political effects. Moreover, the expressive approach to partisanship predicts that a coalition identity will increase positive ratings of all coalition parties and their leaders whereas a primary party affiliation would suggest higher ratings for one’s own party than coalition parties. The identity approach to partisanship thus lends itself well to the study of party affiliations in multi-party systems, opening several new avenues for research.

In conclusion, we urge the adoption of a multi-item partisan identity scale in political behavior research to better assess citizens’ attachment to a political party. This is especially important at a time of declining partisanship in Europe. We have demonstrated that strong identifiers remain loyal to their party and continue to support it electorally. At the highest levels of partisan identity, this electoral support is almost universal regardless of country. But it is also the case that in-party voting is much reduced at lower levels of identity strength. It is thus important to track partisan identity over time with the best measures available in order to understand why and how it changes in response to political events and systems (Huber et al. 2005). The accurate measurement of partisanship is also important from a normative democratic perspective. In the current research, strong partisan identities increased political activity in all three countries. If partisanship is part of the glue that ties citizens to their electoral system, the decline of partisanship is cause for some considerable concern and a worthy topic of further investigation. In the end, a robust measure of partisan identity that is identical across countries may prove to be an important theoretical and empirical addition to research on the study of partisanship and political engagement.

Notes

Instrumental and expressive partisanship are not completely unrelated. Right-left ideology and issue preferences are strongly linked to the direction of partisanship and likely provide an initial impetus to support one party over another. But ideological intensity is only weakly linked to the strength of partisan identity, as we show empirically in this study. Moreover, the stability of partisanship in the face of changing party platforms suggests that issue stances may follow partisanship not vice versa, a proposition at odds with the instrumental model but consistent with numerous studies on elite influence and party cues in the U.S. (Cohen 2003; Dancey and Goren 2010; Druckman et al. 2013; Lenz 2013).

In the following, we largely follow the discussion and notation in De Ayala (2013), pages 209–236.

Roughly 5000 individuals responded to each wave (5195 for the pre, 5225 for post, and 5732 for the values module). For documentation and data, see http://www.lissdata.nl/lissdata/. The 9/12 and 12/12-13/1 waves contained additional items needed for this analysis.

The Panel 8 sample is mainly self-recruited (70 %); the remainder 30 % is a probability-based population sample. The opt-in panel was recruited through internet advertising on the websites of newspapers, Twitter, Facebook and blogs. The second sample (Panel 8.2) was drawn using a probability-based recruitment method only.

Panel members are recruited from various sources including advertising on a wide range of website. For each recruited panel member, YouGov records socio-demographic information in order to ensure a nationally representative adult sample in terms of age, gender, and social class. Everyone taking part in a YouGov survey receives a modest cash incentive for their participation. Data can be downloaded at http://www.britishelectionstudy.com/.

These numbers are based on the entire sample in each country, not just those who received the partisan identity module.

A five-item strength measure (very convinced adherent, convinced adherent, not a convinced adherent, attracted, voted for a party) provides more information than the three-item strength measure on in-party voting in the Netherlands, and its coefficient is comparable in size to that of partisan identity. But it does not account as well as partisan identity for political participation.

Greene used the original IDPG wording which refers to “this group”; we reworded all items to refer to “this party”. Of the 5 items adapted from the IDPG scale, the first three items in Table 2 are taken almost verbatim from the scale. The fourth and fifth items in Table 2 were dramatically reworded. The original item “I have a number of qualities typical of members” was reworded to “I have a lot in common with other supporters of the party” and “If a story in the media criticized this group, I would feel embarrassed” was reworded to “If this party does badly in opinion polls, my day is ruined.” The last three items in Table 2 were newly added to the scale.

Respondents without a party preferences were not asked the partisan identity questions. In Sweden this included those who said they did not feel close to any party, did not want to, or did not answer the question resulting in the omission of 254 respondents. In the Netherlands, 499 respondents were dropped because they were not a supporter nor attracted to a party, had not voted, or left the question blank. In wave 3 of the BES, roughly 13 % (3616) of respondents in the full sample did not provide a party preference. Similarly, 13 % of respondents (2234) in wave 4 of the BES did not indicate a party preference.

We rely on more numerous data from wave 3 for the IRT analysis and wave 4, which contains a political engagement question battery, for the regression analyses.

The Graded Response Model is an extension of the two-parameter logistic (2PL) model for graded response data in the sense that it allows the discrimination parameter α to vary across items.

The theoretical range of theta is −∞ to ∞. However, typical item locations fall within a range of −3 to 3 (De Ayala 2013).

We also calculated the total information provided by each identity item and traditional partisanship strength (Table A2 in the Online Appendix). In each country, the traditional partisan strength item captures less information than any individual partisan identity scale item, and thus provides far less information than the overall partisan identity scale.

Due to similar wording of some items, the error terms for the following items covaried: "When I speak about this party, I usually say ‘we’ instead of ‘they’” and "When I speak about this party, I refer to them as "my party."; "When people criticize this party, it feels like a personal insult" and "When people praise this party, it makes me feel good” as well as "I have a lot in common with other supporters of this party" and "When I meet someone who supports this party, I feel connected with this person." For detailed instructions on how to use the lavaan package, see Hirschfeld and von Brachel (2014).

To further examine whether one or more specific items undermined scalar invariance, we re-ran the invariance analysis and dropped each item in turn. These analyses are included Table A3 (Online Appendix). They suggest that item 8 contributes a little more than other items to weak scalar invariance.

These numbers are obtained from the scalar invariance model for continuous data. Results remain valid if we compare the EPC-interest values to latent mean differences in partisan identity scores obtained from a model for categorical data.

These percentages remain stable across waves 3 and 4.

In the Netherlands, political activities included: (1) making use of a political party or organization, (2) participation in a government-organized public hearing, discussion or citizen participation meeting, (3) contacting a politician or civil servant, or (4) participating in a political discussion or campaign by Internet, e-mail or SMS. In Sweden, activities included (1) contacting a politician, (2) given/raised money to/for a political organization, (3) contacting a civil servant, or (4) attending a political rally. All four questions were repeated in two earlier panel waves, Citizen Panel 5 (11/12/12-12/16/12) Citizen Panel 7 (6/12/13-7/8/13). All 12 items (4 items in 3 waves) were additively combined and rescaled on a 0 to 1 scale. In the U.K., all respondents in wave 4 were asked whether they had visited the website of a candidate or party, signed up or registered online to help a party or candidate, read or found information in the last four weeks tweeted by (1) political parties or candidates, (2) a personal acquaintance, or (3) others, such as a commentator, journalist, or activist, or obtained information from each of these three sources. Five additional questions asked whether the respondent has shared political information through (1) Facebook, (2) Twitter, (3) email, (4) instant messaging or (5) another website or online platform.

Party leaders were evaluated on a scale that ranged from 0 (strongly dislike) to 1 (strongly like) in wave 4 of the BES.

Results in the Netherlands are robust to type of analysis when re-run as an ordered probit model (since the political participation variable has only 5 points).

References

Adams, J., Ezrow, L., & Somer-Topcu, Z. (2011). Is anybody listening? Evidence that voters do not respond to european parties’ policy statements during elections. American Journal of Political Science, 55(2), 370–382. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00489.x.

Allen, M. J., & Yen, W. M. (2001). Introduction to measurement theory. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, Bengt. (2014). Multiple-group factor analysis alignment. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(4), 495–508.

Barrett, P. (2007). Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 815–824.

Bartle, J., & Bellucci, P. (Eds.). (2014). Political parties and partisanship: Social identity and individual attitudes. London: Routledge.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonnet, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness-of-fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606.

Brader, T. A., & Tucker, J. A. (2009). What’s left behind when the party’s over: Survey experiments on the effects of partisan cues in Putin’s Russia. Politics & Policy, 37(4), 843–868.

Brader, T., Tucker, J. A., & Duell, D. (2013). Which parties can lead opinion? Experimental evidence on partisan cue taking in multiparty democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 46(11), 1485–1517.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage Focus Editions, 154, 136.

Burden, B. C., & Klofstad, Casey A. (2005). Affect and cognition in party identification. Political Psychology, 26(6), 869–886.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (1999). Testing factorial invariance across groups: A reconceptualization and proposed new method. Journal of Management, 25(1), 1–27.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255.

Coenders, M., & Scheepers, P. (2003). The effect of education on nationalism and ethnic exclusionism: An international comparison. Political Psychology, 24(2), 313–343.

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 85, 808–822.

Dalton, R. J., & Wattenberg, M. P. (2002). Parties without partisans: Political change in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford University Press.

Dalton, R. J., & Weldon, S. (2007). Partisanship and party system institutionalization. Party Politics, 13(2), 179–196.

Dancey, L., & Goren, P. (2010). Party identification, issue attitudes, and the dynamics of political debate. American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 686–699.

Davidov, E. (2009). Measurement equivalence of nationalism and constructive patriotism in the ISSP: 34 countries in a comparative perspective. Political Analysis, 17(1), 64–82.

De Ayala, R. J. (2013). Theory and practice of item response theory. New York City: Guilford Publications.

Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E., & Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 57–79.

Ellemers, N., Kortekaas, P., & Ouwerker, Jaap W. (1999). Self-categorisation, commitment to the group and group self-esteem as related but distinct aspects of social identity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(2–3), 371–389.

Fernandez-Vazquez, P. (2014). And yet it moves: The effect of election platforms on party policy images. Comparative Political Studies, 47(14), 1919–1944.

Garry, J. (2007). Making party identification more versatile: Operationalising the concept for the multiparty setting. Electoral Studies, 26(2), 346–358.

Garzia, D. (2013). Changing parties, changing partisans: The personalization of partisan attachments in Western Europe. Political Psychology, 34(1), 67–89.

González, R., Manzi, J., Saiz, J. L., Brewer, M., Tezanos-Pinto, D., Torres, D., & Aldunate, N. (2008). Interparty attitudes in Chile: Coalitions as superordinate social identities. Political Psychology, 29(1), 93–118.

Green, D. P., & Palmquist, B. (1990). Of artifacts and partisan instability. American Journal of Political Science, 34, 872–902.

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identity of voters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Greene, S. (1999). Understanding party identification: A social identity approach. Political Psychology, 20, 393–403.

Greene, S. (2002). The social-psychological measurement of partisanship. Political Behavior, 24(3), 171–197.

Greene, S. (2004). Social identity theory and political identification. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 138–153.

Hagevi, M. (2015). Bloc identification in multi-party systems: the case of the Swedish two-bloc system. West European Politics, 38(1), 73–92.

Hirschfeld, G., & von Brachel, R. (2014). Multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis in R-A tutorial in measurement invariance with continuous and ordinal indicators. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 19(7), 2.

Holmberg, S. (1994). Party identification compared across the Atlantic. In K. Jennings & T. E. Mann (Eds.), Elections at home and abroad: Essays in honor of Warren E. Miller (pp. 93–121). University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor.

Horn, J. L., & McArdle, J. J. (1992). A practical and theoretical guide to measurement invariance in aging research. Experimental Aging Research, 18, 117–144.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, Peter M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, Peter M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

H, J. D., Kernell, Georgia, & Leoni, Eduardo L. (2005). Institutional context, cognitive resources and party attachments across democracies. Political Analysis, 13(4), 365–386.

Huddy, Leonie. (2001). From social to political identity: A critical examination of social identity theory. Political Psychology., 22, 127–156.

Huddy, L. (2013). From group identity to political commitment and cohesion. In Leonie Huddy, David O. Sears, & Robert Jervis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 737–773). New York: Oxford University Press.

Huddy, L., & Khatib, N. (2007). American patriotism, national identity, and political involvement. American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 63–77.

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, Lene. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(01), 1–17.

Johnston, R. (2006). party identification: Unmoved mover or sum of preferences? Annual Review of Political Science, 9(1), 329–351.

Kayser, M. A., & Wlezien, Christopher. (2011). Performance pressure: Patterns of partisanship and the economic vote. European Journal of Political Research, 50(3), 365–394.

Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2014). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research,. doi:10.1177/0049124114543236.

Leach, C. W., et al. (2008). Group-level self-definition and self-investment: A hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 144–165.

Lenz, G. S. (2013). Follow the leader?: how voters respond to politicians' policies and performance. University of Chicago Press.

Mael, F. A., & Tetrick, Lois E. (1992). Identifying organizational identification. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(4), 813–824.

Medeiros, M., & Noël, A. (2013). The forgotten side of partisanship: Negative party identification in four Anglo-American democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 47(7), 1022–1046.

Meffert, M. F., Gschwend, T., & Schütze, N. (2009). Coalition preferences in multiparty systems. Presented at Annual Conference of the International Society of Political Psychology, Dublin, Ireland.

Neely, F. (2007). Party identification in emotional and political context: A replication. Political Psychology, 28(6), 667–688.

Nicholson, S. P. (2012). Polarizing cues. American Journal of Political Science, 56(1), 52–66.

Oberski, D. L. (2014). Evaluating sensitivity of parameters of interest to measurement invariance in latent variable models. Political Analysis, 22(1), 45–60.

Pérez, E. O., & Hetherington, M. J. (2014). Authoritarianism in black and white: Testing the cross-racial validity of the child rearing scale. Political Analysis, 22(3), 398–412.

Rizopoulos, D. (2006). ltm: An R package for latent variable modeling and item response theory analyses. Journal of Statistical Software, 17(5), 1–25.

Samejima, F. (1970). Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometrika, 35(1), 139.

Samejima, F. (1974). Normal ogive model on the continuous response level in the multidimensional latent space. Psychometrika, 39(1), 111–121.

Thomassen, J. (1976). Party identification as a cross-national concept: Its meaning in The Netherlands. In I. Budge, I. Crewe, & D. Farlie (Eds.), Party identification and beyond: Representations of voting and party competition (pp. 63–79). London: Wiley.

Thomassen, J., & Rosema, M. (2009). Party identification revisited. In B. John & B. Paolo (Eds.), Political parties and partisanship: Social identity and individual attitudes (pp. 42–59). London: Routledge/ECPR Studies in European Political Science.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–70.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the directors of the LISS, Swedish Citizen Panel, and the British Election Study for the opportunity to include items in their ongoing surveys. We also wish to thank Stanley Feldman, Jacob Sohlberg, Yanna Krupnikov, Patrick Kraft, Michelle Torres, and a number of other colleagues who provided comments and helpful insight on the project. The survey data used in this paper as well as the replication files are available at the journal’s page on Dataverse: (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/polbehavior).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bankert, A., Huddy, L. & Rosema, M. Measuring Partisanship as a Social Identity in Multi-Party Systems. Polit Behav 39, 103–132 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9349-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9349-5