Abstract

The strength of an individual’s identification with their political party is a powerful predictor of their engagement with politics, voting behavior, and polarization. Partisanship is often characterized as primarily a social identity, rather than an expression of instrumental goals. Yet, it is unclear why some people develop strong partisan attachments while others do not. I argue that the moral foundation of Loyalty, which represents an individual difference in the tendency to hold strong group attachments, facilitates stronger partisan identification. Across two samples, including a national panel and a convenience sample, as well as multiple measures of the moral foundations, I demonstrate that the Loyalty foundation is a robust predictor of partisan strength. Moreover, I show that these effects cannot be explained by patriotism, ideological extremity, or directional effects on partisanship. Overall, the results provide further evidence for partisanship as a social identity, as well as insight into the sources of partisan strength.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The political party an individual identifies with, and the strength with which they hold that identity, is central to understanding political behavior. Partisan cues help simplify the political world, providing guidance on which candidates and issues to endorse (e.g., Arceneaux 2007; Boudreau and MacKenzie 2014; Bullock 2011; Nicholson 2012), which facts to believe and how to interpret them (Bartels 2002; Bisgaard 2015; Gaines et al. 2007; Jerit and Barabas 2012), which values to endorse (Goren 2005; Goren et al. 2009) and how to apply them (Petersen et al. 2010).

The effects of partisan identity are clearest among those who strongly identify with their party. Strong partisans are more politically engaged in a variety of ways (e.g., Fowler and Kam 2007; Kenski 2005) and their vote choice is more likely to reflect their interests (Sokhey and McClurg 2012) and partisan identity (Beck 2002). Strong partisans are also more polarized, showing greater discrimination and negative affect towards partisan opponents (Groenendyk and Banks 2014; Huddy et al. 2015; Iyengar et al. 2012; Mason 2015). In short, strong partisans make up the most active and polarized citizens.

How we understand partisanship has critical implications for our interpretation of these findings. Much recent research characterizes partisanship as primarily a social identity (e.g., Green et al. 2004; Groenendyk 2011, 2013; Huddy et al. 2015; Iyengar et al. 2012, 2014; Mason 2015). On this view, the effects of partisanship on political attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors are interpreted as efforts to uphold and defend one’s group identity. In contrast, others take an instrumental approach, viewing partisanship as a product of retrospective evaluations of the parties, as well as policy and ideological goals (e.g., Achen 2002; Fiorina and Morris 1981; Weinschenk 2010). Which model best describes partisanship holds important implications for the nature and quality of public opinion. If the social identity model is more accurate, then the signal sent to politicians through polls and the voting booth may be more an expression of group identity than substantive policy goals.

In spite of the normative importance of understanding the nature of partisanship, it is difficult to disentangle these two perspectives. Political scientists often compare the ability of partisanship and policy or ideological attitudes to predict various political beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors (e.g., Huddy et al. 2015; Iyengar et al. 2012; Mason 2015). Yet, without knowing what drives people to form strong partisan identities in the first place, this common method is limited in its ability to resolve the debate. As one example, partisan divides in factual beliefs have long been taken as evidence for the social identity model (e.g., Bartels 2002), yet many patterns of partisan divides in factual beliefs are also consistent with Bayesian updating (Bullock 2009). Thus, understanding why some people form strong partisan identities in the first place is crucial to interpreting a wide body of literature on partisan identity.

I contribute to this goal by examining what leads people to form strong partisan identities. Drawing on the social identity approach to partisanship, I test the hypothesis that the strength of partisan identity is, in part, a function of a more general dispositional tendency to form strong group attachments. Using a national sample, I show that the moral foundation of Loyalty, and not other moral foundations, consistently predicts stronger partisan identification. A series of robustness tests show that this effect occurs among both Democrats and Republicans and that it cannot be explained by patriotism. Next, I replicate these findings on a convenience sample using multiple measures of the moral foundations. Finally, I demonstrate that the Loyalty foundation has downstream effects, increasing the intention to vote, an effect that is mediated by partisan strength. Overall, the results support the view that partisanship is influenced by a general tendency to moralize group attachment, providing new evidence for partisanship as a social identity. The findings also demonstrate the broader utility of the moral foundations for understanding political and social identities.

Group Loyalty as a Moral Foundation

Psychological research on morality has undergone an affective turn in the past two decades. According to the social intuitionism model, moral judgment is an intuitive process, characterized by automatic, affective reactions to stimuli (Haidt 2001). In other words, moral judgment is to a large extent the product of gut responses, while reasoning is more likely post hoc justification than a cause of moral judgment. Moral foundations theory categorizes these intuitions that drive moral judgment into “foundations” (Haidt and Graham 2007; Haidt and Joseph 2004). Each foundation represents a set of intuitions that have evolved to solve recurrent social dilemmas. For example, cheating and free-riding are constant threats to gains from cooperation, and the Fairness foundation evolved as a set of intuitions and emotions that help to regulate cheating.

The current and most widely accepted draft of the theory posits five foundations, though proponents argue there are likely more (Graham et al. 2013; Iyer et al. 2012). Moral foundations theory holds that there are two classes of moral concerns: individualizing foundations that focus on the well-being of the individual (Care/harm and Fairness/cheating) and binding foundations that focus on the group or society (Authority/subversion, Loyalty/betrayal, and Sanctity/degradation). The Care foundation represents a set of responses to perceived suffering or need and motivates nurturing or protective behavior. As mentioned above, the Fairness foundation is an adaptive response to collective action problems and motivates concerns about reciprocity, including anger and punitive behavior towards those who are perceived to be cheaters or free-riders.Footnote 1 The Authority foundation stems from hierarchical social structures. This foundation motivates obedience, respect, and deference towards strong leaders and authority figures. The Sanctity foundation has its roots in the emotion of disgust as a response to potential pathogens. Sanctity motivates concerns about cleanliness, chastity, and purity, all of which serve to keep the body and mind healthy.Footnote 2

Finally, I turn to the last foundation, Loyalty, which is central to my argument. The Loyalty foundation represents a “sense of attachment and obligation to groups that we identify with (e.g., family, sports team, church, or country)” (Koleva et al. 2012, p. 185) and “helps individuals form strong alliances with others” (Johnson et al. 2016, p. 57). Loyalty leads to approval of “those who sacrifice for the group (e.g., soldiers) or those who contribute to its cohesion and well-being” (Koleva et al. 2013, p. 185) and is exemplified by virtues like loyalty, patriotism, and self-sacrifice (Clifford 2014; Graham et al. 2009; Haidt and Graham 2007). Loyalty thus works to coordinate group members against potential threats, while suppressing in-group dissent and criticism (Graham et al. 2013). In short, Loyalty is an expression of coalitional psychology.

The moral foundation of Loyalty coheres well with the social identity literature and the well-known finding that people form group identities easily and on the basis of arbitrary characteristics (Billig and Tajfel 1973). The ability to form and maintain group alliances, as well as the ability to quickly identify allies, constitutes an adaptive advantage (e.g., Pietraszewski et al. 2015). However, socializing with and trusting any stranger poses a number of risks including being harmed or cheated, or contracting an illness (Kurzban et al. 2001). The Loyalty foundation reflects this logic and motivates behavior that maintains in-group trust while promoting distrust of threatening out-groups (Haidt and Graham 2007).Footnote 3

Existing research suggests that Loyalty originates as an adaptive response to threatening environments. Consistent with this argument, belief in a dangerous world drives endorsement of the binding foundations, including Loyalty (Federico et al. 2013; van Leeuwen and Park 2009). Additionally, Right-Wing Authoritarianism, a disposition involving concerns about order, convention, and tradition (as opposed to openness) that is motivated by belief in a dangerous world, is consistently related to higher endorsement of the binding foundations (Federico et al. 2013; Graham et al. 2011; Milojev et al. 2014).Footnote 4 As a specific example of a social threat, broad social networks pose the threat of exposure to pathogens (for recent discussion, see Aarøe et al. 2016). Pathogen threat motivates lower levels of openness (Schaller and Murray 2008) and generalized trust (Aarøe et al. 2016) and higher levels of conformity (Murray et al. 2011) and authoritarianism (Murray et al. 2013). Pathogen threat, both in terms of regional variation and individual perceptions, also predicts higher levels of binding foundations (Leeuwen et al. 2016; van Leeuwen et al. 2012). Thus, group loyalty seems to be, at least in part, an adaptive response to social dangers.

Empirical Applications of the Loyalty Foundation

Existing applications of moral foundations theory to politics have focused primarily on directional effects (i.e., liberal vs. conservative attitudes). The individualizing foundations, Care and Fairness, consistently predict more liberal political ideology and attitudes, while the binding foundations, Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity, reliably predict more conservative ideology and attitudes (Clifford et al. 2015; Graham et al. 2009; Kertzer et al. 2014; Koleva et al. 2012; Weber and Federico 2013). These findings also hold outside of the United States (Graham et al. 2011), including in independent tests of the theory (Davies et al. 2014; Nilsson and Erlandsson 2015).

The Loyalty foundation is a particularly strong predictor of policy stances that uphold American interests and identity. For example, Loyalty predicts support for increased defense spending, the use of torture on suspected terrorists, the war on terror, and opposition to flag burning and gun control (Koleva et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2014). In the realm of foreign policy, Loyalty is associated with more militant and less cooperative foreign policy stances, including support for the Iraq War, carrying out strikes on Iran, and opposition to the Kyoto Protocol (Kertzer et al. 2014). In short, Loyalty tends to predict conservative political attitudes, particularly on issues in which the United States is perceived as competing against other countries and groups.

Outside of the political domain, recent work demonstrates that the Loyalty foundation predicts stronger group attachments more generally, as well as the behavioral consequences of group attachment. In a close parallel to arguments made about partisan identity, people higher in the Loyalty foundation more strongly identify as sports fans, consistent with the hypothesis that team sports are a byproduct of coalitional psychology (Winegard and Deaner 2010). Loyalty is also associated with greater personal religiousness and commitment to one’s religious group (e.g., through donations; Johnson et al. 2016). The Loyalty foundation sheds light on attitudes towards whistleblowing as well—people high in Loyalty are less likely to support reporting the unethical behavior of their group to an outside group (Waytz et al. 2013). However, Loyalty also predicts willingness to sacrifice individual in-group members (such as coworkers) for the greater good of the group (Crone and Laham 2015). Overall, several recent studies focusing on different groups and topics find evidence that the Loyalty foundation serves to bind people together into groups and promote loyalty to the goals of that group.

Partisanship as a Group Identity

While some view partisanship as a running tally (Fiorina and Morris 1981; Weinschenk 2010), evidence is accumulating that partisans often behave like loyal sports fans. Indeed, many people self-report that their partisanship is an important part of their personal identity (e.g., Greene 1999, 2004) and partisan identities are highly stable over time (Green et al. 2004). This stability stems partly from motivated reasoning strategies that serve to minimize any potential shift away from one’s partisan identity. For example, when faced with information that challenge one’s partisan identity, people often use a “lesser of two evils” justification that involves calling to mind negative information about the out-party in order to balance out negative information about the in-party (Groenendyk 2011). Similarly, when made aware of issue conflicts with one’s own party, respondents tend to place less importance on that issue as a strategy of minimizing the effect on partisan identity (Groenendyk 2013). In short, some partisans seem willing to suppress their own interests in order to maintain their identity.

Partisans are not only motivated to uphold their own identities, but also to defend their group’s reputation and interests. Recent research on party cues suggest that they are not merely heuristics used to simplify the information environment, but instead serve to signal group interests that ought to be defended (Petersen et al. 2012; Pietraszewski et al. 2015). Strong partisans defend their parties in a variety of ways and even openly admit that winning elections and debates is more important than using fair tactics (Miller and Conover 2015). Partisans place greater trust in co-partisans (Carlin and Love 2011; Hetherington et al. 2015), and discriminate against their partisan opponents even in non-political domains (Gift et al. 2014; Iyengar et al. 2014).

Overall, there is considerable evidence that partisanship operates similarly to other social identities, yet we know less about what drives people to form strong partisan identities. To the extent that the Loyalty foundation operates as a more general tendency to form strong group attachments, Loyalty should predict stronger partisan identities. Existing research provides some suggestive evidence for this hypothesis, but it has not been directly tested. There is some evidence that partisans are more likely to be “strong reciprocators” who contribute more to public goods and punish non-contributors at higher rates than non-partisans (Smirnov et al. 2010). In this sense, partisans seem to be more sensitive to cooperative dynamics within groups. Research on personality traits consistently finds that people who are more extraverted tend to have stronger partisan identities (Bakker et al. 2015a, b; Gerber et al. 2012). This finding is typically explained in terms of group identity, as extraverted individuals are more inclined to seek out opportunities for social interaction and politics provides such an opportunity. However, existing research has not directly tested whether differences in group attachment contribute to the formation of partisan strength.

My primary hypothesis is that Loyalty predicts stronger partisan identities. However, I have no clear expectations for the effects of the remaining four foundations. Some have argued that concerns about reciprocity in cooperative games are positively related to partisan strength (Smirnov et al. 2010). Fairness, though, is related to greater willingness to report in-group violations to authorities (Waytz et al. 2013), suggesting it might work against the strength of partisan identity. People high in the Authority foundation might find partisan identities appealing as a source of order and certainty, but authoritarianism tends to be negatively related to political engagement (Hetherington and Weiler 2009). Finally, Care and Sanctity tend to have the strongest directional effects on political ideology, and there is no clear reason why either would motivate partisan strength.

In the next section, I provide the first test of the claim that individual differences in the propensity to moralize group attachment predict partisan strength. I first show that the Loyalty foundation predicts partisan strength and that this effect cannot be explained by patriotism, ideology, or ideological extremity. Second, I replicate these effects in a convenience sample using multiple measures of the moral foundations. Third, I demonstrate that Loyalty has a downstream effect on partisan behavior—increasing the intention to vote—that is partially mediated by partisan strength. Overall, the evidence supports the claim that the strength of partisan identity is in part a result of individual differences in the tendency to form group identities.

Data and Methods

To test these hypotheses, I rely on the 2008–2009 American National Election Studies (ANES) Panel, which tracked respondents between January 2008 and September 2009. Respondents were recruited using random-digit-dialing and invited to complete surveys online.Footnote 5 Between 1420 and 2665 respondents completed each wave of the survey, though panel attrition and item non-response reduce the effective sample sizes in the analyses below, which range between 762 and 911.Footnote 6 In addition to ten political waves, the panel included 11 “off-wave” questionnaires that were written and partially funded by other investigators. The Wave 7 panel, fielded in July 2008 included a shortened 20-item version of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ; Graham et al. 2011). The scale consists of two sections: one that asks respondents to rate the moral relevance of various considerations and a second that asks about agreement with a series of statements. The Loyalty foundation is measured as the average of two relevance items and two agreement items (α = .64). All of the moral foundations are rescaled to range from zero to one.Footnote 7 The two relevance items ask about “Whether or not someone did something to betray his or her group” and “Whether or not someone’s action showed love for his or her country.” The two agreement items state “I am proud of my country’s history” and “People should be loyal to their family members, even when they have done something wrong.” Full question-wording for the MFQ is shown in the Online Appendix and the full questionnaires can be found online through the American National Election Studies website. While two of the four items are about one specific group identity—patriotism—the analysis below shows that results are driven by Loyalty, but not patriotism.

The MFQ has been extensively validated using large, diverse samples (Graham et al. 2011). Confirmatory factor analysis supports the theorized five-factor structure, a finding that holds up in many different countries and regions of the world and has been independently replicated in New Zealand (Davies et al. 2014), Sweden (Nilsson and Erlandsson 2015), and Turkey (Yilmaz et al. 2016). The foundations show criterion validity with related scales and predict attitudes towards theoretically relevant social groups (Graham et al. 2011).Footnote 8

As the primary dependent variable, I rely on a folded measure of partisanship, such that zero represents a pure independent and three represents a strong partisan (e.g., Gerber et al. 2012). Partisanship was measured only in Waves 1 (January ‘08), 9 (September ‘08), 10 (October ‘08) 11 (November ’08), 17 (May ‘09), and 19 (July ‘09). In the analyses below, I focus on Waves 9 and 19 as both contain measures of patriotism. Wave 9 is also the first wave following measurement of the moral foundations to include partisanship, while Wave 19 was measured approximately a year later. In addition, I rely on an index of partisan strength, which consists of the average level of partisan strength across all waves. To simplify analysis and maintain consistency with the single-item measures, the index is split into quartiles.Footnote 9 Analysis of each individual wave is shown in Table A1 in the Online Appendix and reaches similar substantive conclusions.

To test an alternative hypothesis that the results are driven by patriotism, I rely on two different measures of patriotism and nationalism included in the ANES panel. The first is a single-item measure of nationalism asking respondents whether or not the United States is the “greatest nation in the world” (coded 1 for “greatest nation” and 0 for “not the greatest nation”). The second is a more detailed five-item measure of patriotism, which captures more variation and should be more reliable than a single-item measure (Ansolabehere et al. 2008). The five items ask about love for the U.S., feelings about the American flag, supporting the country, the morality of U.S. government actions, and criticism of the U.S. Each item is rescaled to range from zero to one, then averaged (α = .64).

Below I model each measure of partisan strength using an ordered logit model (bivariate correlations between the key dependent and independent variables are shown in Table A2 in the Online Appendix). Consistent with past research, each model includes controls for the remaining four moral foundations, which is important due to moderate to high correlations between the foundations.Footnote 10 Past research has shown that the moral foundations are consistent predictors of political ideology (Graham et al. 2009; Weber and Federico 2013), so I also control for self-reported ideology and ideological extremity in order to ensure that any effects on partisan strength are not being driven by political ideology.Footnote 11 Finally, I also control for a set of sociodemographic variables that are known to influence political engagement and partisan strength: education, income, gender, age, church attendance, and whether the respondent is African American.

Results

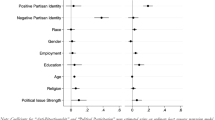

The results for the Wave 9 measure of partisan strength are shown in the first column of Table 1. As expected, the Loyalty foundation significantly predicts stronger partisan identification (p < .01). None of the other four moral foundations are significant predictors. The second column shows the results predicting the Wave 19 partisan strength, which was measured about a year after the moral foundations. Again, the Loyalty foundation predicts greater partisan strength (p < .01). Surprisingly, Fairness is also a significant predictor of partisan strength, but as shown below, this finding is not consistent across the various tests. The third column contains the index of partisan strength averaged across survey waves. Loyalty once again predicts greater partisan strength (p < .001).Footnote 12

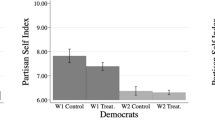

While the first two models controlled for ideology and ideological extremity, it still might be possible that the effects of Loyalty are largely directional and only increase partisan strength among Republicans. To test this alternative explanation, I repeat the previous analyses of Waves 9 and 19 while splitting the sample by partisanship.Footnote 13 The fourth column of Table 1 tests the Wave 9 measure of partisan strength while excluding Republican identifiers and Republican leaners. Loyalty remains a significant predictor of partisan strength (p < .01). The fifth column repeats the same analysis on Wave 19 and Loyalty is again a significant predictor of partisan strength (p < .01). The two rightmost columns show these analyses excluding Democrats and Democratic leaners. In both cases, Loyalty is a statistically significant predictor of partisan strength (ps < .05). Notably, the coefficients are similar in magnitude across the Democratic and Republican models and Wald tests fail to reject the null hypothesis that the coefficients are equal in size (Wave 9: p = .90; Wave 19: p = .77). Thus, Loyalty predicts partisan strength equally well regardless of whether Democrats or Republicans are excluded from the sample.

To illustrate the substantive effects of Loyalty on partisan strength, I estimated the change in partisan strength resulting from a change from one standard deviation below the mean in Loyalty to one standard deviation above the mean, holding all other variables at their central tendencies. Effects are estimated from the first two models in Table 1. Beginning with Wave 9, the probability of being a strong partisan is 14 % at one standard deviation below the mean of Loyalty. Increasing Loyalty to one standard deviation above the mean increases the predicted probability of being a strong partisan by 8 percentage points to 22 %. An identical shift in Loyalty in the Wave 19 data shows an increase in the probability of being a strong partisan from 13 to 21 %, for an increase of 8 percentage points. For comparison, a two standard deviation shift of education leads to increases of 4–6 percentage points, suggesting Loyalty has a substantively meaningful effect on partisan strength.

Testing Patriotism as an Alternative Explanation

The MFQ measure of Loyalty includes two items related to loyalty to one’s country, leading to concerns that the Loyalty foundation might be instead capturing the effects of patriotism. I address this concern below in multiple ways—by controlling for patriotism, controlling for nationalism, and removing the patriotism items from the MFQ scale. Each test supports the hypothesis that the Loyalty foundation increases partisan strength.

As a first test, I rely on the single-item measure of nationalism embedded in Wave 9. The first column of Table 2 reproduces the model from Table 1 while also controlling for the contemporaneous measure of nationalism. Loyalty remains a significant predictor of partisan strength (p < .01), while nationalism is not a significant predictor (p = .61). As a second test, I turn to the Wave 19 data, which includes the five-item measure of patriotism. Notably, this test is biased in favor of patriotism as it is measured in the same wave as partisan strength, while the moral foundations were measured approximately 1 year earlier. Column 2 of Table 2 displays the results of a model predicting Wave 19 partisan strength with the inclusion of patriotism as a control. Loyalty remains a significant predictor (p = .01), while patriotism does not significantly predict partisan strength (p = .31).

As a further test, I removed the two patriotism items from the Loyalty scale and re-estimated the Wave 9 and Wave 19 models from Table 1. The resulting Loyalty measure consists of only two items, which mention loyalty to one’s family and betraying one’s group. In spite of the relatively poor two-item measure of Loyalty, it remains a significant predictor of partisan strength in both Wave 9 and Wave 19 (ps < .05; results shown in columns 3 and 4 of Table 2). As a final test, the last two columns re-estimate the Wave 9 and Wave 19 models with the reduced two-item measure of Loyalty while also controlling for either nationalism (Wave 9) or patriotism (Wave 19). Loyalty remains positive and statistically significant in both models (ps < .05), while neither nationalism nor patriotism significantly predict partisan strength (p = .33, p = .13, respectively). Overall, the results suggest that patriotism cannot explain the effects of Loyalty.

Testing Extremity as an Alternative Explanation

Another alternative interpretation of the data is that Loyalty simply motivates more extreme political attitudes. As noted above, however, all of the results hold while controlling for ideological extremity, which is inconsistent with this explanation. To further rule out this interpretation, I modeled two measures of ideological extremity (Waves 1 and 10) as a function of the moral foundations and demographic controls. The full model results are shown in Table A3 in the Online Appendix, but Loyalty is not a significant predictor of ideological extremity in either wave (p = .38, p = .29). Thus, Loyalty predicts the strength of partisan attachment but not the extremity of one’s ideological views.

Replication Study

To provide an additional test of the Loyalty hypothesis, I rely on a sample of 858 undergraduates recruited from required introductory political science courses at a large public university in the southern United States during the fall of 2014. Subjects completed an approximately 30-min survey covering a variety of political topics. The study was administered online, which tends to yield data of comparable quality to lab-based studies (Clifford et al. 2014). A total of 833 subjects completed the survey and are retained for analysis. Although it is a convenience sample, it is demographically and politically diverse: 42 % male, 16 % black, 38 % Hispanic, and 19 % were not born in the United States. As for political identity, 35 % identified as Democrats, 23 % as Republicans, and the mean ideological score was 3.5 on a 1–7 scale (where 7 is very conservative).

Although the sample is clearly not nationally representative, it allows improved measurement of the moral foundations, which would be prohibitively costly in a nationally representative survey. The moral foundations were measured using the full 30-item MFQ, improving upon the 20-item measure used in the ANES study. In addition, this study included an alternative measure of the moral foundations relying on 29 moral foundations vignettes (MFVs), each depicting a person violating one of the foundations (Clifford et al. 2015).Footnote 14 Respondents were asked to rate the moral wrongness of each behavior. Full question-wording is shown in the Online Appendix, but examples of Loyalty violations include “a man leaving his family business to go work for their main competitor,” “a teacher publicly saying she hopes another school wins the math contest,” and “a former US General saying publicly he would never buy any American product.” Each foundation is measured as the average wrongness rating of the corresponding vignettes. All measures of the foundations are rescaled to range from zero to one. Clifford et al. (2015) validated a larger set of MFVs by showing a similar factor structure to the MFQ, demonstrating criterion validity with the MFQ, and analyzing respondents’ interpretations of why the scenarios are wrong. In short, the MFVs are not redundant to the MFQ, but tap into similar concepts. Partisan strength is again operationalized as a folded partisan identification scale, ranging from zero to three.

Following a similar approach to the models above, I predict partisan strength using an ordered logit model (summary statistics and bivariate correlations are shown in Table A4 in the Online Appendix). Control variables include the remaining moral foundations, ideology, ideological extremity, and sociodemographics. Below I present two separate models, each relying on a different measure of the moral foundations.

Results

The results for the model using the MFQ measure of the moral foundations are shown in the first column of Table 3. As expected, the Loyalty foundation is a significant predictor of partisan strength (p < .01), but none of the remaining foundations have a statistically significant effect. Column 2 displays a similar model utilizing the MFV measures of the moral foundations, rather than the MFQ. Loyalty is again a significant predictor of partisan strength (p < .001), while none of the other foundations are significant predictors. These findings demonstrate further support for the hypothesis using both the full 30-item MFQ and a new measure of the moral foundations based on judgments of concrete scenarios.

The Benefits of Loyal Partisans

The Loyalty foundation predicts partisan strength, but is the effect large enough to affect downstream behaviors? According to the social identity approach to partisanship, “the strongest partisans will work most actively to increase electoral victory and partisan group status” (Huddy et al. 2015, p. 3) and this has been one of the most consistent effects of partisan strength. Thus, people high in Loyalty should be more motivated to turn out to support their team, and this effect should be mediated by partisan strength. To test this hypothesis, I rely on the ANES data described above. As indicators of political participation, I rely on three measures. The first two are measures of the intention to vote in the upcoming 2008 presidential election, which were asked in Waves 9 (September) and 10 (October).Footnote 15 The third measure is self-reported voter turnout, asked in Wave 11 (November). I predict each measure using a logit model and the same set of control variables used in Table 1 above.

The results are shown in Table 4. As expected, the Loyalty foundation predicts higher vote intention in both Wave 9 (p = .02) and Wave 10 (p = .01). None of the other foundations have statistically significant effects, with the exception of Authority, which predicts lower vote intention in both models (ps < .05), a finding that is consistent with research on authoritarianism (Hetherington and Weiler 2009). Finally, the last column of Table 4 shows the results for self-reported turnout. Again, the coefficient on Loyalty is positive, however, it is not statistically significant (p = .55). Thus, Loyalty generates stronger intentions to vote, but the effects are not large enough to increase actual turnout behavior.

To test whether partisan strength mediates these effects, I turn to the causal mediation framework (Imai et al. 2010, 2011) using the mediation package in Stata (Hicks and Tingley 2011). To satisfy the sequential ignorability assumption, I control for the same set of covariates used above in both stages of the model (for a similar approach, see Gadarian and Albertson 2014).Footnote 16 Because the model results are similar to those shown in Tables 1 and 4, I discuss the key results here while showing the model details in the Online Appendix (see Table A5). As expected, the results show that partisan strength is a significant mediator of the effect of Loyalty on Wave 9 vote intention (p < .05). Turning to the Wave 10 results, partisan strength again significantly mediates the effect of Loyalty (p < .05). For the turnout model, the total effect of Loyalty on turnout is not statistically significant, however, there is a significant mediating effect of partisan strength (p < .05). Overall, the results are consistent with the prediction that Loyalty increases political engagement, at least for vote intentions, and partisan strength mediates this effect.

Do Republicans Have a Loyalty Advantage?

So far, the results show that Loyalty predicts greater partisan strength and may have downstream effects, such as increased political engagement. As a result, political parties likely benefit from loyal group members. Yet, because aspects of conservative political ideology are more appealing to individuals high in the Loyalty foundation (e.g., Clifford et al. 2015; Graham et al. 2009; Weber and Federico 2013), the benefits of group Loyalty may disproportionately accrue to the Republican party. To examine the size of this potential advantage, I rely on simulations based on the ANES Wave 9 model shown in the first column of Table 1 above. Among Democrats (including leaners), the mean value of Loyalty is 0.63. Among Republicans, this value is significantly higher at 0.71. Holding all other variables at their central tendencies, I simulated the effect of increasing Loyalty from 0.63 to 0.71. For Democratic levels of Loyalty, the estimated probability of being a strong partisan is 17 %. At Republican levels of Loyalty, this probability increases to 19 %. Thus, while Republicans do tend to score higher in the Loyalty foundation, which in turn translates into higher levels of partisan strength, this two percentage point increase is unlikely to generate meaningful gains in turnout, cooperation, or polarization. Nonetheless, the public is becoming better ideologically sorted (e.g., Levendusky 2009; Mason 2015). As the two parties become more ideologically distinct, the Loyalty gap between Democrats and Republicans may become even larger. Thus, partisan sorting may increase the size of the partisan Loyalty gap and the corresponding benefits to the Republican party.

Conclusion

Political scientists increasingly portray partisanship as more of a team sport than an instrumental investment in policies or outcomes, downplaying the role of ideological and issue-based concerns in political behavior and attitudes (e.g., Groenendyk 2011, 2013; Huddy et al. 2015; Iyengar et al. 2012). Support for this social identity perspective has come from a variety of methods, such as self-reports of social identity (e.g., Greene 1999, 2004), group favoritism (Miller and Conover 2015), and discriminatory behavior (Gift et al. 2014; Iyengar et al. 2014). Yet, it leaves open the question of why some people come to strongly identify with a party, even if the party is not closely aligned with their beliefs and interests.

Across two studies and multiple measures of the moral foundations, the findings here demonstrate that the Loyalty foundation is a robust predictor of the strength of partisan identity, providing support for the social identity approach to partisanship. These findings suggest that some people are more inclined to form strong group attachments than others, and hence more likely to become strong partisans. A series of robustness tests show that this effect cannot be explained by patriotism or political ideology and the effects are similar among both Democrats and Republicans. As with virtually all research on partisanship and partisan strength, these studies rely on observational designs (for an exception, see Gerber et al. 2010), raising questions about whether the effects are causal. However, the results are consistent with expectations across a variety of tests and several alternative explanations have been ruled out. Thus, while firm causal claims cannot be made, the evidence suggests that people who moralize group loyalty are more likely to form strong partisan identities.

While these results provide support for the social identity approach to partisanship, they do not imply that instrumental goals, such as particular policy outcomes, are unimportant to the formation of partisan identities. For example, an instrumental goal, such as one’s stance on abortion, may contribute to the formation of or change in one’s partisan identity (e.g., Adams 1997; Carsey and Layman 2006). While the initial impetus may have been instrumental, people high in Loyalty may be more likely to then form a strong partisan identity. In this sense, Loyalty may enhance the effects of instrumental goals that bring an individual into a party and strengthen their identification with it. However, if an individual’s instrumental goals shift over time, or the parties’ positions on the topic shift, a party identification retained due to feelings of group loyalty may come to be less representative of one’s instrumental goals. Thus, an important area for future research is to analyze how Loyalty, partisan identity, and instrumental goals evolve together over time, particularly among young voters who are still forming their partisan identities (e.g., Alwin and Krosnick 1991).

The results presented here were highly consistent across multiple data sources and measures, yet they focused only on the United States and covered a limited time frame. Taking on the latter point, the ongoing process of partisan sorting may play a role in the relationship between Loyalty and partisan strength. Given that the moral foundations, including Loyalty, are more strongly related to ideology than to partisan strength, partisan sorting should increase the relationship between the moral foundations and partisanship.Footnote 17 As a result, the Loyalty gap between Democrats and Republicans should become larger, leading to stronger partisan identification among Republicans. Turning to the issue of geography, there is considerable cross-cultural variability in the moral foundations, and Loyalty tends to be higher in Eastern countries (Graham et al. 2011). Thus, Loyalty may help explain cross-cultural variation in the strength of partisan attachments. Yet, partisan attachments also depend on the institutions that structure political parties. An important question that remains to be answered is how individual differences in Loyalty interact with the structure and dimensionality of party systems to create partisan attachments.

In addition to lending insights to the nature of partisan identity, the findings here contribute to research on moral foundations theory. Previous work applying moral foundations theory to politics has largely focused on directional effects, demonstrating associations between the binding foundations and conservative political attitudes and identities (Clifford et al. 2015; Graham et al. 2009; Kertzer et al. 2014; Koleva et al. 2012; Weber and Federico 2013). This has led some to worry that the Loyalty foundation captures little more than patriotism or ideological sentiments. However, the findings here demonstrate a non-directional effect of Loyalty on the strength of political identity. Moreover, this effect remained after controlling for patriotism, which itself did not predict partisan strength. These findings help demonstrate the validity of the Loyalty foundation as a measure of general group loyalty and also point to future research questions. If Loyalty serves to strengthen a variety of group identities, then it may have multi-faceted effects on political attitudes and identities. For example, a strong racial identity may drive a white voter to hold more conservative political attitudes (Jardina 2014), but lead an African American voter to more liberal attitudes (e.g., Dawson 2001). In this sense, the effects of Loyalty on political attitudes may be mediated by multiple identities. Yet, because identities can have cross-cutting effects on partisan identity (Brader et al. 2014), Loyalty could even lead to weaker partisan identities among cross-pressured subgroups. Thus, exploring how Loyalty affects a broader set of group identities will provide a more nuanced understanding of how the Loyalty foundation affects political attitudes and ideologies.

Notes

Originally the Fairness foundation was described in terms of equality and rights, however, more recent research understands Fairness in terms of reciprocity (Haidt 2013).

However, just because a particular intuition or moral foundation was adaptive does not imply that it continues to be adaptive in modern society.

In this sense, Loyalty should promote lower generalized trust, but higher particularized trust (e.g., Uslaner and Brown 2005).

Some of this work interprets personality traits and sociopolitical orientations (e.g., RWA) as causally prior to the moral foundations. Yet, recent work questions common assumptions about the causal relationship between traits, values, and ideologies (Kandler et al. 2014). Thus, more research designed to draw causal inferences will be needed to resolve this question.

Respondents who did not have internet service were offered free internet access for the duration of the study. Further details can be found through the American National Election Studies website.

The Wave 7 sample size was smaller than some of the other waves. Only 1053 respondents in this wave completed the full MFQ.

Internal reliability of the Loyalty foundation and remaining foundations (Care: α = .65, Fairness: α = .67, Authority: α = .65, Sanctity: α = .73) is similar to previous work (Graham et al. 2011).

Initial evidence suggests that the foundations are stable over time (Graham et al. 2011), but more recent evidence calls this into question (Smith et al. 2016). Smith et al. (2016) tested the stability of the foundations over a longer period of time, but relied on a poor measure of the foundations (Haidt 2016), so the cumulative evidence is ambiguous.

The particular measures making up the index varies across individuals depending on the number of waves completed and item non-response. Several alternative methods to scoring the index were also tested and make no substantive difference to the results.

In spite of the moderate correlations between the foundations, multicollinearity does not seem to be problematic. The average variance inflation factor ranges from 1.51 to 1.52 in the key models reported below and never rises above 2.20 for any of the individual coefficients. Moreover, the results hold when omitting the controls for the remaining moral foundations.

Ideology is measured using a standard 7-point self-placement scale. Ideological extremity is measured using this same question folded at the midpoint of the scale.

I do not perform this analysis on the index because it is unclear how to split the measure into Democrats and Republicans given that some individuals change their partisanship over time. Ideological extremity is excluded from the models due to the collinearity with ideology that occurs after removing entire partisan groups.

In addition to the 29 vignettes used here, the study also included five vignettes measuring the Liberty foundation (Iyer et al. 2012) and 4 vignettes representing non-moral social violations. These are not used in the analysis.

These questions asked whether respondents “expect to vote in the national elections this coming November, or not?”.

The package does not allow for ordinal mediators, so linear regression is used to model partisan strength.

Indeed, in the ANES sample used here, Loyalty, and the moral foundations more generally, tend to be more strongly related to ideology than to partisanship.

References

Aarøe, L., Osmundsen, M., & Petersen, M. B. (2016). Distrust as a disease-avoidance strategy: Individual differences in disgust sensitivity regulate generalized social trust. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1038.

Achen, C. H. (2002). Parental Socialization and Rational Party Identification. Political Behavior, 24(2), 151–170.

Adams, G. D. (1997). Abortion: Evidence of an issue evolution. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 718.

Alwin, D. F., & Krosnick, J. A. (1991). Aging, cohorts, and the stability of sociopolitical orientations over the life span. American Journal of Sociology, 97(1), 169–195.

Ansolabehere, S., Rodden, J., & Snyder, J. M. (2008). The strength of issues: Using multiple measures to gauge preference stability, ideological constraint, and issue voting. American Political Science Review, 102(2), 215–232.

Arceneaux, K. (2007). Can partisan cues diminish democratic accountability? Political Behavior, 30(2), 139–160.

Bakker, B. N., Klemmensen, R., Nørgaard, A. S. & Schumacher, G. (2015). “Stay loyal or exit the party? How openness to experience and extroversion explain vote switching.” Political Psychology.

Bakker, B. N., Hopmann, D. N., & Persson, Mikael. (2015b). Personality traits and party identification over time. European Journal of Political Research, 54(2), 197–215.

Bartels, L. M. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(2), 117–150.

Beck, P. A. (2002). Encouraging political defection: The role of personal discussion networks in partisan desertions to the opposition party and perot votes in 1992. Political Behavior, 24(4), 309–337.

Billig, M., & Tajfel, H. (1973). Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 3(1), 27–52.

Bisgaard, M. (2015). Bias will find a way: economic perceptions, attributions of blame, and partisan-motivated reasoning during crisis. The Journal of Politics, 77(3), 849–860.

Boudreau, C., & MacKenzie, S. A. (2014). Informing the electorate? How party cues and policy information affect public opinion about initiatives. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 48–62.

Brader, T., Tucker, J. A., & Therriault, A. (2014). Cross pressure scores: An individual-level measure of cumulative partisan pressures arising from social group memberships. Political Behavior, 36(1), 23–51.

Bullock, J. G. (2009). Partisan bias and the Bayesian ideal in the study of public opinion. The Journal of Politics, 71(3), 1109.

Bullock, J. G. (2011). Elite influence on public opinion in an informed electorate. American Political Science Review, 105(3), 496–515.

Burden, B. C. (2008). The Social roots of the partisan gender gap. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(1), 55–75.

Carlin, R. E., & Love, G. J. (2011). The politics of interpersonal trust and reciprocity: an experimental approach. Political Behavior, 35(1), 43–63.

Carsey, T. M., & Layman, G. C. (2006). Changing sides or changing minds? Party identification and policy preferences in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 464–477.

Clifford, S. (2014). Linking issue stances and trait inferences: A theory of moral exemplification. The Journal of Politics, 76(3), 698–710.

Clifford, S., & Jerit, J. (2014). Is there a cost to convenience? An experimental comparison of data quality in laboratory and online studies. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 1(02), 120–131.

Clifford, S., Iyengar, V., Cabeza, R., & Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (2015). Moral foundations vignettes: A standardized stimulus database of scenarios based on moral foundations theory. Behavior Research Methods, 47(4), 1178–1198.

Crone, D. L., & Laham, S. M. (2015). Multiple moral foundations predict responses to sacrificial dilemmas. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 60–65.

Davies, C. L., Sibley, C. G., & Liu, J. H. (2014). Confirmatory factor analysis of the moral foundations questionnaire: Independent scale validation in a new zealand sample. Social Psychology, 45(6), 431–436.

Dawson, M. C. (2001). Black visions: The roots of contemporary African–American political ideologies. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Federico, C. M., Weber, C. R., Ergun, D., & Hunt, C. (2013). Mapping the connections between politics and morality: The multiple sociopolitical orientations involved in moral intuition. Political Psychology, 34(4), 589–610.

Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Retrospective voting in American National Elections. London: Yale University Press.

Fowler, J. H., & Kam, C. D. (2007). Beyond the self: Social identity, altruism, and political participation. The Journal of Politics, 69(3), 813–827.

Gadarian, S. K., & Albertson, B. (2014). Anxiety, immigration, and the search for information. Political Psychology, 35(2), 133–164.

Gaines, B. J., et al. (2007). Same facts, different interpretations: Partisan motivation and opinion on iraq. The Journal of Politics, 69(4), 957–974.

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., Doherty, D., & Dowling, C. M. (2012). Personality and the strength and direction of partisan identification. Political Behavior, 34(4), 653–688.

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., & Washington, E. (2010). Party affiliation, partisanship, and political beliefs: A field experiment. American Political Science Review, 104(4), 720–744.

Gift, K., & Gift, T. (2014). Does politics influence hiring? Evidence from a randomized experiment. Political Behavior, 37(3), 653–675.

Goren, P. (2005). Party identification and core political values. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 881–896.

Goren, P., Federico, C. M., & Kittilson, M. C. (2009). Source cues, partisan identities, and political value expression. American Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 805–820.

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1029–1046.

Graham, J., et al. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 366–385.

Graham, J., et al. (2013). Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 55–130.

Green, D. P., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2004). Political parties and the social identities of voters: Partisan hearts and minds. London: Yale University Press.

Greene, S. (1999). Understanding party identification: A social identity approach. Political Psychology, 20(2), 393–403.

Greene, S. (2004). Social identity theory and party identification*. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 136–153.

Groenendyk, E. (2011). Justifying party identification: A case of identifying with the ‘Lesser of Two Evils’. Political Behavior, 34(3), 453–475.

Groenendyk, E. (2013). Competing motives in the partisan mind: How loyalty and responsiveness shape party identification and democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Groenendyk, E. W., & Banks, A. J. (2014). Emotional rescue: How affect helps partisans overcome collective action problems. Political Psychology, 35(3), 359–378.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834.

Haidt, J. (2013). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion (Vintage). New York: Vintage.

Haidt, J. (2016). “Are moral foundations heritable? Probably.” RighteousMind.com. Retrieved November 7, 2016, from http://righteousmind.com/are-moral-foundations-heritable-probably.

Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 98–116.

Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2004). Intuitive ethics: How innately prepared intuitions generate culturally variable virtues. Daedalus, 133(4), 55–66.

Hetherington, M. J., & Rudolph, T. J. (2015). Why Washington won’t work: polarization, political trust, and the governing crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hetherington, M. J., & Weiler, J. D. (2009). Authoritarianism and polarization in American politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hicks, R., & Tingley, D. (2011). Causal mediation analysis. The Stata Journal, 11(4), 605–619.

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17.

Imai, K., Keele, L., & Tingley, D. (2010). A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 15(4), 309–334.

Imai, K., Keele, L., Tingley, D., & Yamamato, T. (2011). Unpacking the black box of causality: Learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. American Political Science Review, 105(4), 765–789.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2014). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 1–47.

Iyer, R., et al. (2012). Understanding libertarian morality: The psychological dispositions of self-identified libertarians. PLoS One, 7(8), e42366.

Jardina, A. E. (2014). Demise of dominance: Group threat and the new relevance of white identity for American politics. Michigan: University of Michigan.

Jerit, J., & Barabas, J. (2012). Partisan perceptual bias and the information environment. The Journal of Politics, 74(3), 672–684.

Johnson, K. A. et al. (2016). “Moral foundation priorities reflect U.S. Christians’ individual differences in religiosity.” Personality and Individual Differences.

Kandler, C., Zimmermann, J., & McAdams, D. P. (2014). Core and surface characteristics for the description and theory of personality differences and development. European Journal of Personality, 28(3), 231–243.

Kenski, K. (2005). Who watches presidential debates? A comparative analysis of presidential debate viewing in 2000 and 2004. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(2), 213–228.

Kertzer, J. D., Powers, K. E., Rathbun, B. C., & Iyer, R. (2014). Moral support: How moral values shape foreign policy attitudes. The Journal of Politics, 76(3), 825–840.

Koleva, S. P., et al. (2012). Tracing the threads: How five moral concerns (especially purity) help explain culture war attitudes. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(2), 184–194.

Koleva, S., et al. (2013). The Moral compass of insecurity: Anxious and avoidant attachment predict moral judgment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(2), 185–194.

Kurzban, R., Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2001). Can race be erased? Coalitional computation and social categorization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98(26), 15387–15392.

Levendusky, M. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberals became democrats and conservatives became republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mason, L. (2015). ‘I disrespectfully agree’: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128–145.

Miller, P. R., & Conover, P. J. (2015). Red and blue states of mind: partisan hostility and voting in the united states. Political Research Quarterly, 68(2), 225–239.

Milojev, P., et al. (2014). Right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation predict different moral signatures. Social Justice Research, 27(2), 149–174.

Murray, D. R., Schaller, M., & Suedfeld, P. (2013). Pathogens and politics: Further evidence that parasite prevalence predicts authoritarianism. PLoS One, 8(5), e62275.

Murray, D. R., Trudeau, R., & Schaller, M. (2011). On the origins of cultural differences in conformity: Four tests of the pathogen prevalence hypothesis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(3), 318–329.

Nicholson, S. P. (2012). Polarizing cues. American Journal of Political Science, 56(1), 52–66.

Nilsson, A., & Erlandsson, A. (2015). The Moral foundations taxonomy: Structural validity and relation to political ideology in Sweden. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 28–32.

Norrander, B. (1997). The independence gap and the gender gap. Public Opinion Quarterly, 61(3), 464–476.

Petersen, M. B., Skov, M., Serritzlew, S., & Ramsøy, T. (2012). Motivated reasoning and political parties: Evidence for increased processing in the face of party cues. Political Behavior, 35(4), 831–854.

Petersen, M. B., Slothuus, R., & Togeby, L. (2010). Political Parties and value consistency in public opinion formation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74(3), 530–550.

Pietraszewski, D., et al. (2015). Constituents of political cognition: race, party politics, and the alliance detection system. Cognition, 140, 24–39.

Schaller, M., & Murray, D. R. (2008). Pathogens, personality, and culture: Disease prevalence predicts worldwide variability in sociosexuality, extraversion, and openness to experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 212–221.

Smirnov, O., et al. (2010). The behavioral logic of collective action: Partisans cooperate and punish more than nonpartisans. Political Psychology, 31(4), 595–616.

Smith, Kevin B. et al. 2016. “Intuitive Ethics and Political Orientations: Testing Moral Foundations as a Theory of Political Ideology.” American Journal of Political Science.

Smith, I. H., Aquino, K., Koleva, S., & Graham, J. (2014). The moral ties that bind. even to out-groups: The interactive effect of moral identity and the binding moral foundations. Psychological Science, 25(8), 1554–1562.

Sokhey, A. E., & McClurg, S. D. (2012). Social networks and correct voting. The Journal of Politics, 74(3), 751–764.

Uslaner, E. M., & Brown, M. (2005). Inequality, trust, and civic engagement. American Politics Research, 33(6), 868–894.

van Leeuwen, F., & Park, J. H. (2009). Perceptions of social dangers, moral foundations, and political orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(3), 169–173.

van Leeuwen, F., Park, J. H., Koenig, B. L., & Graham, J. (2012). Regional variation in pathogen prevalence predicts endorsement of group-focused moral concerns. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33(5), 429–437.

van Leeuwen, F., Dukes, A., Tybur, J & Park, J. (2016). “Disgust sensitivity relates to moral foundations independent of political ideology.” Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences.

Waytz, A., Dungan, J., & Young, L. (2013). The whistleblower’s dilemma and the fairness–loyalty tradeoff. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(6), 1027–1033.

Weber, C. R., & Federico, C. M. (2013). Moral foundations and heterogeneity in ideological preferences. Political Psychology, 34(1), 107–126.

Weinschenk, A. C. (2010). Revisiting the political theory of party identification. Political Behavior, 32(4), 473–494.

Winegard, B., & Deaner, R. O. (2010). The evolutionary significance of Red Sox nation: Sport fandom as a by-product of coalitional psychology. Evolutionary Psychology, 8(3), 432–446.

Yilmaz, O., Harma, M., Bahçekapili, H. G., & Cesur, Sevim. (2016). Validation of the moral foundations questionnaire in Turkey and its relation to cultural schemas of individualism and collectivism. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 149–154.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Brad Jones and Spencer Piston for helpful comments. Replication materials are available on the Political Behavior Dataverse.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clifford, S. Individual Differences in Group Loyalty Predict Partisan Strength. Polit Behav 39, 531–552 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9367-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9367-3