Abstract

Negative partisanship captures the notion that disdain for the opposing party is not necessarily accompanied by strong in-party attachments. Yet, lack of a theoretical framework as well as measurement issues have prevented researchers from utilizing this consequential concept. I address these concerns in several ways. First, I design and examine the measurement properties of a multi-item scale that gauges negative partisan identity. Second, I demonstrate that—while most Americans display aspects of both negative and positive partisan identity—the two are distinct constructs. Third, I compare the power of both types of partisan identity in predicting attitudes towards bipartisanship, political participation, and vote choice. I thereby demonstrate the distinctive effects of negative and positive partisan identity on a range of political behaviors. The results offer a more nuanced perspective on partisanship and its role in driving affective polarization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The 2016 presidential election was marked by widespread negativity: Instead of enthusiastically embracing their party’s presidential nominee, many voters used their vote to signal their opposition to the other party. In a poll conducted by the Pew Research Center in the months leading up to the 2016 elections, Americans overwhelmingly reported feeling angry with the other party while a much smaller share cited feeling enthusiastic about their own party.Footnote 1 This asymmetry is not just an election artifact: In February 2018, another nationally representative poll revealed that 71% of Republicans and 63% of Democrats cite the harm from the opposing party’s policies as a major reason to affiliate with their own party.Footnote 2 These polls are indicative of the rise of negative partisanship among Americans.

The term ‘negative partisanship’ captures the idea that strong out-party hostility can develop without equally strong in-party attachments. Despite the wealth of research on affective polarization (e.g. Lelkes and Westwood 2017; Miller and Conover 2015; Iyengar and Westwood 2015; Iyengar et al. 2012; Mason 2015; Rogowski and Sutherland 2016), negative partisanship has not received much scholarly attention on its own. As Caruana et al. (2015, p. 771) put it: “…the volume of scholarship that investigates negative partisanship is dwarfed by the body of literature that considers positive partisanship.” While recent work has shown a strong correlation between partisan strength and disdain for the out-party (Miller and Conover 2015; Mason 2015), some earlier research in political science (Maggiotto and Piereson 1977; Weisberg 1980) as well as social psychology (Allport 1954; Brewer 1999) suggests that strong in-party attachments do not have to involve hostility towards the out-party.

Despite the face validity of this argument, there is only little empirical evidence that party attachments—positive partisanship as I will refer to it in this manuscript—are necessarily linked to negative partisanship. This manuscript addresses this gap in several ways: First, I introduce a multi-item scale that measures negative partisan identity (NPID). The scale goes beyond simply measuring negative affect and provides a measure that is theoretically equivalent to identity-based measures of positive partisan identity. Utilizing a confirmatory factor analysis, I demonstrate that positive and negative partisanship are indeed distinct constructs. I advance this argument by examining the power of positive and negative partisan identity in predicting attitudes towards bipartisanship, vote choice, and political engagement in the 2016 presidential elections as well as vote intention in the 2018 U.S. House elections.

Overall, the evidence presented in this manuscript delivers the relatively positive message that strong partisans are not condemned to demonize the other party. I conclude the article with a discussion of these results’ normative implications as well as future research avenues.

Negative and Positive Partisanship

While prior work on affective polarization (Mason 2015; Miller and Conover 2015; Abramowitz and Webster 2016; Bafumi and Shapiro 2009; Rogowski and Sutherland 2016) has demonstrated an increasing correlation between the strength of party attachments and negative affect towards the other party, political scientists have yet to examine to what extent positive and negative partisanship necessarily occur simultaneously. One of the few contributions to address this question comes from Abramowitz and Webster (2015) who demonstrate that positive and negative partisanship do not move in parallel. Instead, even weak partisans in the U.S. now hold negative views of the out-party. Thus, strong partisan ties are not a requirement for the development of negativity towards the other party. This notion is also echoed by Iyengar et al. (2012):Using the American National Election Study, the authors show that partisans’ ratings of the opposing party have become increasingly negative over time. At the same time, partisans’ affect towards their own party has remained relatively stable. Thus, negative affect towards the out-party does not move in tandem with strong positive affect towards the in-party.

While this type of research emerged recently within the context of affective polarization in the U.S., Campbell (1980, p. 121) already hinted at the possibility of negative partisanship in their pioneering work ‘The American Voter’: “…the political party serves as the group toward which the individual may develop an identification, positive or negative, of some degree of intensity” (emphasis added). Thus, the notion of negative partisanship was established at the same time as political scientists started to embrace the idea of partisanship as an identity. Nevertheless, positive partisanship has remained the focus of our investigations. Maggiotto and Piereson’s work (1977) presents an early exception: The authors question the relationship between the strength of in-party identification and out-party evaluations, stating that “…there is no reason to expect the traditional measure of partisan identification to be perfectly related to attitudes toward the opposition party” (p. 747). The authors show that evaluations of Democrats and Republicans are indeed relatively independent of one another, suggesting that opposition to the out-party does not necessarily grow with the strength of in-party attachments.

Outside the context of the U.S. two-party system, Rose and Mishler (1998) make the case for negative partisanship in post-Communist countries. The authors develop a fourfold typology of open, negative, closed, and apathetic partisans: Open partisans exhibit positive partisanship toward their in-party without negative partisanship toward another party while negative partisans exhibit negative partisanship without positive partisanship. Closed partisans, on the other hand, possess both a negative and positive identification while apathetic partisans possess no identification. Rose and Mishler argue that these four combinations also have different consequences for partisans’ political behavior, emphasizing the important distinction between positive and negative partisanship. Despite this early evidence in support of negative partisanship, the concept itself, let alone its measurement, has not nearly received as much attention as its positive counterpart.

The Measurement of Negative Partisanship

Long before research on affective polarization, Weisberg (1980) noted that the one-dimensional partisanship measure (i.e. strong Democrat–strong Republican) is unable to capture the possible distinction between (and combination of) positive and negative party identification as well as their changing relationship to each other over time. Subsequent work on negative partisanship built on this insight and has utilized a variety of measures to capture negative partisanship: Some scholars have used feeling thermometer (FT) ratings to gauge negative affect towards the out-party (Abramowitz and Webster 2015; Lelkes and Westwood 2017; Mason 2015; Iyengar et al. 2012; Rogowski and Sutherland 2016). From a methodological standpoint, differential item functioning is a frequently cited problem with FTs whereby respondents might use a finer distinction for positive evaluations than for negative ones (see Winter and Berinsky 1999). From a theoretical standpoint, negative affect can be a consequence of a negative (or positive) identity. Social identity researchers have long argued that affective responses to in- and out-groups are largely conditioned by social identities whereby the strongest group identifiers are most likely to report strong affective reactions to electoral threat and reassurance (Greene 1999; Huddy et al. 2015; Rydell et al. 2008; van Zomeren et al. 2008). At the same time, a negative identity is not a necessary condition for negative affect. For example, voters can hold strong negative affect towards political objects that they do not identify with.Footnote 3

A handful of researchers have suggested measuring negative partisanship more explicitly: Medeiros and Noël (2014) use the question “Is there any party you would never vote for?” to gauge negative partisanship in multi-party systems (also see Rose and Mishler 1998). The authors find that negative and positive partisanship significantly impact vote choice whereby positive partisanship had a much stronger effect than its negative counterpart. These results are intuitive for multi-party systems, in which vote choice can be seen as a more affirmative act than in a two-party system where a vote for one party could feasibly be interpreted as a vote against the other. While Medeiros and Noel’s study is one of the first to compare and contrast the predictive power of negative and positive partisanship, the authors do not elaborate on potential measurement concerns. For example, the measure of positive partisanship might not be equivalent to the measure of negative partisanship. Similarly, it is unclear whether the ‘negative vote’ item captures negative affect or thoughts, or maybe even a strategic decision not to vote for a party that has low chances of winning in the first place. Caruana et al. (2015) try to address these questions to a certain extent by expanding the measure of negative partisanship: In their work, the party for which the respondent would never vote and which received a FT value below 50 is considered the target of negative partisanship. While this dichotomous measure entails an affective component, it does not account for variations in the intensity of negative partisanship. Just like variations in the strength of positive partisanship matter for predicting political behavior (see Huddy et al. 2015), so might variations in the intensity of negative partisanship. While the authors find a unique influence of negative partisanship on Canadian political behavior, it is possible that their measurement strategy underestimates the effect of negative partisanship.

Finally, the measurement of negtive partisan identity is particularly relevant for research on the instrumental and expressive origins of partisanship (see Huddy et al. 2015). It is possible, for example, that partisans assign a low FT score to the out-party because of opposite policy views (i.e. instrumental) or because of status-related threats (i.e. expressive). FT values as well as the ‘negative vote’ item cannot distinguish between these two dimensions while a measure of negative partisan identity aims to focus on expressive components of negative partisanship—a point on which I elaborate in the next section.

The Case for Negative Partisan Identity

The previous review revealed two major shortcomings in the current literature on negative partisanship: First, the lack of a theoretical framework to account for its independent existence and second, the lack of an adequate measurement strategy. In the following section, I will address these points and articulate my hypotheses for the remainder of this manuscript.

Partisanship in the U.S. and beyond is increasingly studied within the framework of Social Identity Theory (SIT; Tajfel and Turner 1979), which has led to the development of an identity-based conceptualization of partisanship (Green et al. 2004; Greene 1999, 2002, 2004; Huddy et al. 2015; Mason 2015) which is broadly based on Mael and Tetrick’s (1992) Identification with a Psychological Group Scale. This multi-item index captures crucial social identity ingredients such as the subjective sense of group belonging, the affective importance of group membership, and the affective consequences of lowered group status (Ellemers et al. 1999; Leach et al. 2008) with items such as “When I meet somebody who supports this party, I feel connected” and “When people praise this party, it makes me feel good”. This (positive) partisan identity scale had good measurement properties and proved to be a better predictor than the standard three-point partisan strength measureFootnote 4 of a range of political variables, including political involvement (Huddy et al. 2015; Bankert et al. 2017).

This social identity framework, I argue, can also be used to derive an understanding of negative partisanship. Specifically, SIT argues that identities cannot only form as a function of common characteristics among in-group members but also in opposition to groups to which we do not belong. Thus, the identity is negative in the sense that it centers on the rejection of the out-group’s characteristics. Zhong et al. (2008a, b) refer to this type of identity as negational.Footnote 5 In the political realm, psychologists have demonstrated that Americans form negative identities in response to third parties (Bosson et al. 2006) as well as political organizations like the National Rifle Association (Elsbach and Bhattacharya 2001), turning the exclusion from a group—the “not being one of them”—into a meaningful social identity.

Naturally, questions arise regarding the origins of these negative identities, in particular their dependency on in-group identities. While some researchers assume the psychological primacy of the in-group in forming negative identities (Allport 1954; Gaertner et al. 2006), Zhong et al. (2008a) argue that for these identities, “…out-groups are ‘psychologically primary’, in the sense that dissimilarity or distance from one’s out-group comes before similarity to or attachment with in-groups” (p. 797). Relevant examples include Occupy Wall Street, the anti-nuclear movement, as well as anti-feminism campaigns since all of these groups formed in response to what they oppose.

Negative and positive identities also differ in their psychological origins: Referring to Balance Theory (Heider 1958) and Optimal Distinctiveness Theory (Brewer 1991), Zhong et al. (2008a, b) argue that positive identities satisfy both basic human desires: the need for inclusion as well as the need for distinctiveness by emphasizing intra-group similarity (i.e. belong to other in-group members) as well as inter-group differences (i.e. being different from out-group members). Negative identities, on the other hand, satisfy the need for distinctiveness to a much larger extent than the need for inclusion. From this perspective, positive and negative partisanship have different psychological antecedents. These insights suggest that a strong in-group identity is not a requirement for the formation of a negational identity. Applied to partisanship, I thus predict that negative and positive partisanship are not the same construct and instead can be fairly distinct (Hypothesis 1).

If negative partisanship is a distinct construct, its measurement becomes essential when examining its effects on political behavior. Prior measurement strategies are not equivalent to the identity-based conceptualization and measurement of partisanship that has gained popularity in the U.S. (Huddy et al. 2015; Mason 2015), making it hard to accurately compare and contrast the effects of negative and positive partisanship. I address this issue by designing a multi-item scale that measures negative partisan identity that closely resembles the positive partisan identity scale. Following Zhong and colleagues’ measurement approach,Footnote 6 I flip the items of the positive partisan identity scale to capture the emotional significance respondents associate with their rejection of the out-party with items such as “When I meet somebody who supports this party, I feel disconnected” and “I get angry when people praise this party”. Using this independent and equivalent measure, I first examine the effect of negative and positive partisanship on attitudes towards bipartisanship. Based on the assumption that in-party attachments do not automatically lead to the rejection of the out-party (Brewer 1991), I predict that negative partisanship is a stronger predictor of opposition to bipartisanship than positive partisanship (Hypothesis 2). Next, I examine political engagement on behalf of the in-party. Given that mobilization by the in-party facilitates political engagement (e.g. Wattenberg 2000), I expect that political engagement is primarily driven by positive partisan identity (Hypothesis 3)—a prediction that is also aligned with prior work by Caruana et al. (2015) who show that positive partisanship is a stronger predictor of party membership and volunteering for a party in Canada than negative partisanship.

Last, I test the effects of negative and positive partisanship on the vote. Caruana et al. (2015) as well as Medeiros and Noël (2014) show that positive partisanship is a stronger predictor of voting for the in-party than negative partisanship. I investigate whether these results hold true with an identity-based measure in the U.S. (Hypothesis 4). However, in the last U.S. presidential election, negative partisanship might have played a greater role for Republicans than for Democrats. In fact, a poll by the Pew Research CenterFootnote 7 revealed that 53% of prospective Trump voters said their vote was primarily a vote against Clinton while 44% said their vote was a vote for Trump. Democratic voters, on the other hand, did not report a similar division. There are possibly two reasons for this asymmetry: First, among Democrats, Trump was not seen as a credible threat to a Democratic Party’s electoral chances. SIT underscores the power of status threats in activating (negative or positive) identities. From this perspective, Republicans might have been more likely to develop a negative partisan identity since a victory of their own party was portrayed as unlikely. Second, party leaders can foster particular types of identity (see Reicher and Hopkins 1996): the rhetoric of the Trump campaign emphasized differences between the Democrats and Republicans while the rhetoric of the Clinton campaign underscored unity (i.e. “stronger together”). Highlighting connections to similar others reduces the tendency to derogate the out-group (Zhong et al. 2008a, b). Thus, I predict that negative partisanship is a stronger predictor of vote choice for Trump (Hypothesis 4a) while positive partisanship is a stronger predictor of vote choice for Clinton (Hypothesis 4b). To further illustrate the susceptibility of positive and negative partisanship to status threats such as elections, I supplement these analyses with an examination of Americans’ vote intention in the 2018 congressional elections. If negative and positive identities respond to threat, then negative partisanship should be a stronger factor in Democrats’ vote decision in the post-2016 congressional elections than for Republicans (Hypothesis 4c).

Note that the following analyses are restricted to partisans, including leaners, since I am mostly interested in disentangling the effects of negative partisan identity (NPID) and positive partisan identity (PPID) . In contrast to Independents, American partisans are much more likely to exhibit both NPID as well as PPID and therefore constitute a more relevant study population. In the following, I discuss the data as well as my measurement choices to test these hypotheses.

Data and Measurement

For the pre-election analyses, I utilize a sample of 1051 U.S. citizens who were part of a panel maintained by Survey Sampling International (SSI). The sample reflects the U.S. population in terms of age, gender, race, and census region. SSI administered the survey online between November 1st and 4th, 2016. 54% of respondents identified with the Democratic Party while 30% identified as Republicans, including strong and weak partisans as well as partisan leaners. This yields an effective sample size of 887 respondents since the following analyses are restricted to partisans and leaners. For the post-election analyses, I rely on data from the 2017 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey (CCES)—a nationally representative sample of 1000 people—that was collected by YouGov in November 2017. The CCES sample contains a higher share of Republican identifiers (40%) and a somewhat similar share of Democratic identifiers (60%) yielding an effective sample size of 748 partisans. For more details on sample features and recruitment, see Appendix.

Independent Variables

Positive Partisan Identity Scale (PPID): In both samples, the positive partisan identity scale is assigned to partisan as well as partisan leaners and entails eight items that gauge respondents’ psychological attachment to their party. The scale consists of items such as “When I talk about this party, I say ‘we’ instead of ‘them’” as well as “I am interested in what other people think about this party”. Response options reflect the frequency of these thoughts and behaviors, ranging from “never/rarely” to “always”. I combine all eight items to create the positive partisan identity scale (alpha = 0.92 in the SSI and 0.89 in the CCES sample). I re-scaled the variable to range from 0 (minimum) to 1 (maximum). Table A1 in the Appendix entails the distribution of response options for each scale item in the SSI sample. The sample’s average PPID value is 0.51.

Negative Partisan Identity Scale (NPID): I adapted the positive partisan identity scale for the assessment of a negative identity by modifying items to refer to the party with which one does not identify. This approach led to items such as “When people criticize this party, it makes me feel good’’ or “When I meet someone who supports this party, I feel disconnected”. Identical to the PPID scale, the NPID scale was assigned to partisans and partisan leaners. Response options ranged again from “never/rarely” to “always” with high reliability (0.88 in the SSI sample and 0.90 in the CCES sample). NPID scale ranges from 0 (minimum) to 1 (maximum). Table A2 in the Appendix shows the distribution for each scale item. The sample’s average NPID value is 0.44.

In order to avoid potential priming effects, the order of the PPID and NPID scale was randomized. Despite claims that negative identities are less frequent (e.g. Zhong et al. 2008a), a relatively high share of partisans in the sample admit to “often” (26%) or “always” (31%) feeling relieved when the out-party loses or thinking that they do not have much in common with supporters of the out-party (26% and 28%).

Dependent Variables

Anti-Bipartisanship: In both samples, negative attitudes towards bipartisanship are measured with an item that asks how frequently respondents think that the goals of the Democratic and the Republican Party are incompatible. Response options range from “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, and “often” to “always”. 20% of Democratic respondents and 23% of Republican respondents indicated that they “always” think that the goals of the Democratic and Republican Party are incompatible while less than 10% of both partisan groups reported “never” encountering that thought.

Political Participation: This variable measures the number of political activities that respondents have done during the 2016 election season such as watching a presidential debate and volunteering for a party. The scale combines seven such items and takes on a value of 0 if the respondent has not engaged in any sort of political activity during the 2016 election season and a value of 1 if the respondent reports having done all of the seven political activities.

Vote Choice in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Elections: This variable reflects partisans’ intention to vote for their party’s candidate. For example, the variable takes on a value of 1 if Democratic respondents indicate voting for Hillary Clinton and 0 if they indicate voting for a different presidential candidate. 80% of partisans reported the intention to vote for their party’s candidate while 20% intended to vote for a different presidential candidate.

Vote Intention in the 2018 U.S. House Elections: In the CCES post-election sample, this survey item asks respondents about their vote intention in the 2018 congressional elections. This variable is coded 0–1, in the same fashion as the 2016 vote choice variable. 21% of respondents reported the intention to vote for an out-party candidate (or being uncertain about their choice) and 79% reported the intention to vote for their in-party candidate.

Control Variables: I control for various factors that are known to impact voting decisions and as well political action such as gender (coded as 1 for female and 0 for male respondents), education, age, religion (coded as 1 for religious and 0 for non-religious respondents), political issue strength,Footnote 8 race (coded as 1 for White and 0 for non-White respondents) and employment status (coded as 1 for employed and 0 for unemployed respondents) at the time the survey was conducted.

PPID and NPID: Two Different Constructs?

The first set of analyses tests the hypothesis that negative and positive partisanship are two distinct constructs (Hypothesis 1). For this purpose, I initially examine the relationship between PPID and NPID. The two variables correlate at 0.58 in the SSI sample,Footnote 9 which suggests they are fairly inter-related. In a next step, I take the median split of negative and positive partisanship and calculate the percentage of respondents with high and low levels on both dimensions as well as the off-diagonals (i.e. high negative partisanship and low positive partisanship and vice versa). After re-scaling all variables to range from 0 to 1, the median for positive partisanship is 0.25 and 0.21 for negative partisanship. The majority of respondents (64%) display high levels of positive and negative partisanship. Nevertheless, there is a significant share of 22% that are located on the off diagonal, combining low and high levels of positive and negative partisanship. Equally surprising is the asymmetry between the high/high and low/low distribution: while 64% display both high levels of negative and positive partisanship, only 15% exhibit both low levels of negative and positive partisanship. These descriptive statistics suggest that negative and positive partisanship are not interchangeable.Footnote 10

To corroborate these results, I conduct a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the negative and positive partisan identity scales. The CFA allows me to test the fit of the two-dimensional structure compared to a one-dimensional one and therefore provides a direct test of my first hypothesis. I first specify a one-factor model whereby the positive and negative partisanship items are defined as measurement variables of the same latent construct. I then contrast this model to a two-factor model whereby positive and negative partisanship are defined as two separate latent constructs. I utilize several fit indices to evaluate the fit of these models including the Chi-Square, the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), as well as the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI). These indices can be found in Table 1.

Every fit index significantly improves when negative and positive partisanship are conceptualized as two separate latent factors rather than one: Ehile Chi-Square and the RMSEA substantially drop, the CFI and TLI values significantly increase, suggesting a better model fit.Footnote 11,Footnote 12

Overall, these results lend support to my first hypothesis that positive and negative partisanship—while undoubtedly related—are two relatively distinct constructs. This first finding justifies further investigations into the effect of negative and positive partisanship on Americans’ political attitudes and behavior.

Bipartisanship Attitudes and Political Participation

To test Hypotheses 2 and 3, I regress anti-bipartisanship and political participation on the two main predictors—positive and negative partisan identity—as well as a set of control variables. Column 1 in Fig. 1 entails the results from these analysesFootnote 13: The coefficient for negative partisanship is statistically significant and substantial in size while positive partisanship does not exert any effect on anti-bipartisanship attitudes. Put differently, strong beliefs that the goals of the Democratic and Republican Party are incompatible are primarily driven by negative partisan identity. It is therefore possible to be strongly attached to one’s party without opposing bipartisan efforts.Footnote 14 Moreover, older and more religious respondents were more likely to see the goals of the two parties as incompatible.

Moving on to political participation in Column 2 of Fig. 1, the analysis reveals the mirror opposite: Positive partisan identity is a strong predictor of political engagement while negative partisan identity does not exert any significant effect on political engagement during the 2016 election season. To further illustrate these results, I calculate the predicted probabilities of political engagement across the range of negative and positive partisan identity: As positive partisanship increases from 0 to 1, the probability of becoming political active increases from 0.15 to 0.35. Thus, political engagement on behalf of the in-party is driven by the strength of one’s attachments to that party rather than the opposition to the out-party. From a normative perspective, this is encouraging since it suggests that people are motivated to support their party because of their genuine connection to it.Footnote 15,Footnote 16

In-Party Vote

Vote choice represents a political activity with a more ambiguous direction, especially in a two-party system like the U.S.: Voting for a party can express support for one party and/or disdain for the other. Teasing apart these different motivations has been difficult due to measurement issues. Using a separate scale for positive and negative partisan identity, however, allows tracing the origins of people’s vote choice in the 2016 presidential elections. First, I regress in-party vote on negative and positive partisanship as well as the previously used set of control variables. As Column 1 in Fig. 2 suggests, both positive and negative partisan identity are significant predictors of voting for the in-party candidate.

Since these results are obtained from a logistic regression model, it is difficult to directly compare the effect of positive and negative partisan identity. Thus, I plotted the predicted probabilities of voting for the in-party in Fig. A2 (see Appendix), affirming the notion that positive partisan identity influences in-party vote to a much larger extent than negative partisan identity: The probability of voting for the in-party rises much more drastically from 0.62 to 0.95 as positive partisan identity increases in strength compared to the relative minor change of 0.1 in the probability across the values of negative partisan identity.Footnote 17 These findings are aligned with prior work on negative partisanship that demonstrates stronger effects of positive partisan identity on the voteFootnote 18 (see Medeiros and Noël 2014).

I further interact negative and positive partisan identity to examine whether high NPID can compensate for low PPID in shaping political behavior. While this interaction does not appear to influence bipartisanship attitudes and political participation, it is a strong, positive, and highly significant predictor of in-party vote. In fact, the probability of in-party vote is almost identical for those with high PPID/low NPID and those with high NPID/low PPID (see Table A14 & Fig. A3 in the Appendix). This result underscores the influence of negative partisan identity.Footnote 19

In-Party Vote for Clinton and Trump

Given the grave hostility towards Hillary Clinton that seemed to unify GOP supporters despite their lukewarm support of Trump, I expect that the effects of negative and positive partisan identity differ for Clinton and Trump supporters. To test this prediction, I conduct two different analyses: One to predict voting for Hillary Clinton among Democrats and one to predict voting for Donald Trump among Republicans. I regress these two dependent variables on the same set of variables used in prior analyses. The results are displayed in Columns 2 and 3 in Fig. 2.Footnote 20 Contrary to the combined analysis of in-party vote in Column 1, in-party vote for Clinton is not driven by negative partisan identity. Positive partisan identity, on the other hand, exerts a strong and positive impact on voting for Clinton among Democrats in addition to gender, education, age, and religion. Thus, the decision to vote for Clinton is influenced by partisans’ attachment to the Democratic Party instead of their disdain for the Republican Party. In contrast, Republicans’ vote for Trump is influenced by both negative and positive partisan identity, as well as race, employment status, education, and political issue strength.

To facilitate the comparison, I illustrate the effects of positive and negative partisan identity on the predicted probability of voting for Trump in Fig. A4 in the Appendix: The probability of voting for Trump increases almost as rapidly across the range of negative partisan identity as across positive partisan identity.Footnote 21 These results suggest that the disdain felt towards the Democrats, and especially Hillary Clinton, might have motivated even reluctant members of the Republican Party to vote for Donald Trump. Interestingly, I do not observe a similar interplay of negative and positive partisan identity among Democrats.Footnote 22,Footnote 23 Given the many discontent voices among GOP supporters regarding their party’s candidate, negative partisanship’s impact might have been exacerbated in shaping Republicans’ vote choice for Trump—a finding that therefore must not necessarily hold true for prior or future elections.

Post-Election Analysis: House Vote

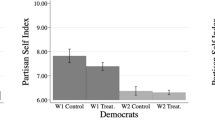

In the last set of analyses, I examine the effect of NPID and PPID on respondents’ vote intention in the 2018 U.S. House election. I regress the House vote intention on to NPID, PPID, and the set of control variable used in earlier analyses. The results can be found in Fig. 3.Footnote 24 The first Column in Fig. 3 demonstrates that—among all respondents—negative partisanship is a significant predictor of voting for the in-party candidate in the House election as is ideological strength,Footnote 25 age, and education. Positive partisanship, on the other hand, does not exert a significant effect. However, examining Republicans only (Column 2 in Fig. 3) reveals that both negative and positive partisanshipFootnote 26 predict the intention to vote for the in-party candidate while among Democrats (Column 3 in Fig. 3), only negative partisanship impacts the House vote intention.

These results suggest that Republicans’ decision to vote for a Republican House candidate is driven by both their strong in-party attachments as well as their disdain for the Democratic Party while Democrats’ decision to vote for a Democratic candidate is first and foremost driven by their opposition to the Republican Party. These results are in line with my predictions and confirm that the power of negative and positive partisanship is not static but rather influenced by dynamic factors such as status, power, and intra-party conflicts. The latter is especially true for the Democratic Party with its current internal struggles regarding the party’s future leadership and ideological orientation.Footnote 27

Discussion

The findings from this research make two important contributions to the study of partisanship. First, negative and positive partisanship are distinct constructs that differentially influence political behavior among Americans. Second, this manuscript establishes a coherent measure of negative partisan identity based on the theoretical framework of Social Identity Theory. Thus, the instrument is well suited for inclusion in studies on affective polarization and other research that aims to test the power of social and political identities in shaping political behavior in the U.S. and beyond. Given the increasing scholarly attention to partisan hostility, research on negative partisanship might benefit from utilizing the negative partisan identity scale. Moreover, the measure’s applicability is not restricted to the U.S. two-party system. In fact, the U.S. presents a particularly tough test case since a two-party system might foster a stronger convergence of positive and negative partisanship. From this perspective, any evidence in support of negative partisanship in the U.S. suggests that these two types of partisanship might exist independently to a much larger extent in multi-party systems. Thus, the negative partisan identity scale might be as useful in studying voters in multi-party systems as its positive counterpart (see Bankert et al. 2017).

Critics might question to what extent the negative partisan identity scale is a better measure of negative partisanship than commonly used measurement strategies. While there is no benchmark for the validation of any measure, a replication of several main analyses with the ‘negative vote’ item as well as the FT value for the out-party leads to significantly different results. For example, using the FT values as a measure for negative partisanship would have produced quite different substantive results (e.g. analysis of voting for Clinton) and it would have underestimated the effects of negative (and positive) partisanship (e.g. analysis of voting for Trump, or anti-bipartisanship attitudes, see Tables A20, A21, A22 & A23 in Appendix). Moreover, the correlations between FT values for the out-party, the negative vote, and the negative partisan identity scale are very low, suggesting that the three variables do not capture the same underlying concept.Footnote 28 In other analyses, however, the three different measures produce quite similar substantive results (e.g. analysis of political participation and in-party vote, see Tables A20 & A21 in Appendix). This variation illustrates that the negative partisan identity scale might be particularly useful in studies that examine differences in voting behavior between Democrats and Republicans as well as partisan hostility.

Despite this assertion, there are also practical concerns about survey space that need to be taken into consideration. Based on the results of the confirmatory factor analysis, three items seem to measure negative partisan identity especially well, namely: “When people criticize this party, it makes me feel good”, “I am relieved when this party loses an election”, and “When I talk about this party, I say ‘they’ instead of ‘we’”. These three items can be used to create a shorter but almost equally reliable version (alpha = 0.84) of the negative partisan identity scale when survey space is limited.Footnote 29

Future research might investigate the mechanisms that lead to the development of negative partisanship independently from or in conjunction with positive partisanship. While positive partisan identity might provoke the development of negative partisan identity, it is not clear to what extent the reverse can be true. It seems feasible though that negative partisan identity can, for example, serve as a superordinate identity that unites a diverse coalition of voters and thereby temporarily facilitates political mobilization. Since negative identities do not provide a psychological sense of belonging, it is possible that negative partisanship is less stable than positive partisanship. On the other hand, Rose and Mishler (1980) argue that many negative partisans in post-Communist countries failed to develop a positive partisanship toward any party and instead have become skeptical of political parties in general without becoming apathetic or apolitical (p. 231). Especially in European multi-party systems, researchers can test the possible development of negative partisanship into a positive one. For example, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (2018) explain that in many Western European democracies, populist parties are the target of negative partisanship despite declining levels of positive partisanship. Future work could examine whether this opposition eventually translates into stronger attachment to mainstream parties. In addition to these institutional features, future research might also investigate to what extent election campaigns and political leaders temporarily heighten negative partisanship by portraying the out-party as a threat to the status and power of the in-party.

Last, negative and positive partisan identity can also be used to examine Independent identities in the U.S. and beyond. Weisberg (1980) makes the case for a more nuanced perspective on Independents: Rather than perceiving them as the simple midpoint between Democrats and Republicans, Independents might negatively identify with a political party or even identify positively with both. This notion resembles Klar and Krupnikov’s work (2016), which suggests that an Independent identity might be negative in the sense that it develops in opposition to established political parties. However, it is also possible that being an Independent is a positive identity that is grounded in voters’ self-image as unbiased and objective observers of politics. These questions can be assessed more carefully with an adequate measure of both positive and negative partisanship.

In conclusion, partisans are able to feel deeply connected to their party without feeling deep disdain for the other party. From a normative standpoint, this is good news for political parties in representative democracies and provides a strong impetus for political scientists to explore the factors that allow partisans to root for their team without vilifying their opponent.

Notes

This poll can be accessed here: https://www.people-press.org/2016/06/22/6-how-do-the-political-parties-make-you-feel/ (last access: 12/20/2018).

This poll can be accessed here: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/03/29/why-do-people-belong-to-a-party-negative-views-of-the-opposing-party-are-a-major-factor/ (last access: 12/20/2018).

I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

The standard three-point partisan strength measure categorizes respondents into partisan leaners, weak partisans, and strong partisans. While it correlates moderately with positive partisan identity, its predictive power is much weaker. To illustrate this point, I replicate the main analyses in this paper with the traditional strength measure.

In the following, I use the terms ‘negational identities’ and ‘negative identities’ interchangeably.

Zhong and colleagues flip the items of the identity subscale designed by Luhtanen and Crocker (1992) who also rely on Social Identity Theory to create their scale.

This poll can be accessed here: https://www.people-press.org/2016/08/18/1-voters-general-election-preferences/#more-negative-voting-than-in-08 (last access 03/14/2017).

‘Political issue strength’ measures respondents’ attitude strength on ten salient issues including abortion, gun control, health care, same-sex marriage, and environmental regulations. The items scale well together (alpha = 0.78). Substituting ideology or ideological intensity for political issue strength does not change any of the results presented in this manuscript.

PPID and NPID correlate at 0.55 in the CCES sample.

For a scatterplot of the relationship between negative and positive partisan identity, see Fig. A1 in the Appendix.

The Chi-Square value of the two-factor model is significantly different from the value of the one-factor model [Chi-Square(df) = 1025.34(1), p < 0.001]. The fit of both models improves when co-variances between error terms are added but the two-factor model remains superior (see Table A4 in Appendix).

An exploratory factor analysis further supports these results (see Tables A5, A6, A7 in Appendix).

The corresponding table can be found in the Appendix (see Table A8) as well as analyses with the standard partisan strength item (see Table A9).

To address concerns regarding potential endogeneity between anti-bipartisanship and negative partisan identity, I replicate this analysis with two other dependent variables (see Table A10 in Appendix).

When predicting less partisan political engagement such as watching a presidential debate and interest in national news, positive partisanship remains a more powerful influence (see Table A11 in Appendix).

I replicate these findings with the CCES sample (see Table A12 in Appendix).

The coefficient for positive partisan identity is indeed statistically bigger than the coefficient for negative partisan identity (p < 0.01).

Similarly, positive partisanship is a predictor of turnout while negative partisanship does not exert any statistically significant effect (see Table A13 in Appendix).

I thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this additional analysis.

The corresponding table can be found in the Appendix (see Table A15 in Appendix).

The coefficients for negative and positive partisan identity are statistically indistinguishable from each other (p < 0.86).

Note that these results are relatively insensitive to the inclusion of feeling thermometer values for Trump and Clinton. The asymmetry between Republicans and Democrats remains (see Table A16 in Appendix).

I replicate these findings with a sample of 1788 undergraduate students. These analyses can be found in the Appendix (see Table A17).

The corresponding table can be found in the Appendix (Table A18).

‘Ideological strength’ was constructed by folding the ideology self-placement measure at its mid-point.

The coefficients for negative and positive partisan identity are statistically indistinguishable from each other (p < 0.53).

These results also hold when controlling for individual preferences for divided government (see Table A19 in Appendix).

The negative partisan identity scale correlates with FT values at − 0.16 and with the negative vote item at 0.33. Figure A5 in the Appendix plots the relationship between the negative partisan identity scale and FT values for the out-party.

References

American Political Science Association. Committee on Political Parties. (1950). Toward a more responsible two-party system: A report (Vol. 44, No. 3). Rinehart: American Political Science Association. Committee on Political Parties.

Abramowitz, A. I., & Webster, S. (2016). The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of US elections in the 21st century. Electoral Studies, 41, 12–22.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Bafumi, J., & Shapiro, R. Y. (2009). A new partisan voter. The Journal of Politics, 71(1), 1–24.

Bankert, A., Huddy, L., & Rosema, M. (2017). Measuring partisanship as a social identity in multi-party systems. Political Behavior, 39, 1–30.

Bosson, J. K., Johnson, A. B., Niederhoffer, K., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2006). Interpersonal chemistry through negativity: Bonding by sharing negative attitudes about others. Personal Relationships, 13, 135–150.

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 429–444.

Campbell, A. (1980). The American voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Caruana, N. J., McGregor, R. M., & Stephenson, L. B. (2015). The power of the dark side: Negative partisanship and political behaviour in Canada. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 48(04), 771–789.

Ellemers, N., Kortekaas, P., & Ouwerker, J. W. (1999). Self-categorisation, commitment to the group and group self-esteem as related but distinct aspects of social identity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(2–3), 371–389.

Elsbach, K. D., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Defining who you are by what you’re not: Organizational disidentification and the National Rifle Association. Organization Science, 12, 393–413.

Gaertner, L., Iuzzini, J., Witt, M. G., & Orina, M. M. (2006). Us without them: Evidence for an intragroup origin of positive ingroup regard. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 426–439.

Green, D. P., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2004). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Greene, S. (1999). Understanding party identification: A social identity approach. Political Psychology, 20(2), 393–403.

Greene, S. (2002). The social–psychological measurement of partisanship. Political Behavior, 24(3), 171–197.

Greene, S. (2004). Social identity theory and party identification. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 136–153.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley.

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(01), 1–17.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology a social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431.

Klar, S., & Krupnikov, Y. (2016). Independent politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leach, C. W., et al. (2008). Group-level self-definition and self-investment: A hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 144–165.

Lelkes, Y., & Westwood, S. J. (2017). The limits of partisan prejudice. The Journal of Politics, 79(2), 485–501.

Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1992). A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(3), 302–318.

Maggiotto, M. A., & Piereson, J. E. (1977). Partisan identification and electoral choice: The hostility hypothesis. American Journal of Political Science, 21, 745–767.

Mason, L. (2015). “I disrespectfully agree”: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128–145.

Medeiros, M., & Noël, A. (2014). The forgotten side of partisanship: Negative party identification in four Anglo-American democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 47(7), 1022–1046.

Miller, P. R., & Conover, P. J. (2015). Red and blue states of mind: Partisan hostility and voting in the United States. Political Research Quarterly, 68(2), 225–239.

Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018). Studying populism in comparative perspective: Reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comparative Political Studies, 51(13), 1667–1693.

Reicher, S., & Hopkins, N. (1996). Self-category constructions in political rhetoric; an analysis of Thatcher’s and Kinnock’s speeches concerning the British miners’ strike (1984–5). European Journal of Social Psychology, 26(3), 353–371.

Rogowski, J. C., & Sutherland, J. L. (2016). How ideology fuels affective polarization. Political Behavior, 38(2), 485–508.

Rose, R., & Mishler, W. (1998). Negative and positive party identification in post-Communist countries. Electoral Studies, 17(2), 217–234.

Rydell, R. J., Mackie, D. M., Maitner, A. T., Claypool, H. M., Ryan, M. J., & Smith, E. R. (2008). Arousal, processing, and risk taking: Consequences of intergroup anger. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(8), 1141–1152.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 33(47), 74.

van Zomeren, M., Spears, R., & Leach, C. W. (2008). Exploring psychological mechanisms of collective action: Does relevance of group identity influence how people cope with collective disadvantage? British Journal of Social Psychology, 47(2), 353–372.

Wattenberg, M. P. (2000). The decline of party mobilization. In Parties without partisans: Political change in advanced industrial democracies (pp. 64–76). https://doi.org/10.1093/0199253099.003.0004.

Weisberg, H. F. (1980). A multidimensional conceptualization of party identification. Political Behavior, 2(1), 33–60.

Winter, N., & Berinsky, A. J. (1999 Rydell). What’s your temperature? Thermometer ratings and political analysis. In Annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Atlanta, GA.

Zhong, C. B., Phillips, K. W., Leonardelli, G. J., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008a). Negational categorization and intergroup behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(6), 793–806.

Zhong, C. B., Galinsky, A. D., & Unzueta, M. M. (2008b). Negational racial identity and presidential voting preferences. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(6), 1563–1566.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Jamie Carson, Joe Ura, Paul Kellstedt, Lilliana Mason, Joshua Robison, Eric Groenendyk, Patrick Kraft, Nicholas Nicoletti, a number of other colleagues, and four anonymous reviewers who provided thoughtful comments and helpful insight on the project. The survey data used in this paper as well as the replication file are available at the journal’s page on Dataverse: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/TDDMIB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bankert, A. Negative and Positive Partisanship in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Elections. Polit Behav 43, 1467–1485 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09599-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09599-1