Abstract

This paper reports on the development and pilot evaluation of a Croatian school-based youth gambling prevention program “Who really wins?”. The program is aimed at minimizing risk and enhancing protective factors related to youth gambling. A short-term evaluation of the program was conducted with a sample of 190 first and second year high-school students (67.6% boys, aged 14–17 years; average age 15.61). An experimental design with two groups (Training vs. No Training) and two measurement sessions (pre-test and post-test sessions) was used to evaluate change in problem gambling awareness, cognitive distortions, knowledge of the nature of random events as well as in social skills. Results showed significant changes in the post-test sessions, which can be attributed to changes in the Training group. We observed a decrease in risk factors, namely better knowledge about gambling and less gambling related cognitive distortions. Immediate effects on protective factors such as problem solving skills, refusal skills, and general self-efficacy were not observed. Findings also show program effects to be the same for both boys and girls, students from different types of schools, for those with different learning aptitudes, as well as for those at different risk levels with regard to their gambling, which speaks in favour of the program’s universality. The program had no iatrogenic effects on behaviour change and shows promise as an effective tool for youth gambling prevention. Future research and a long-term evaluation are needed to determine whether the observed changes are also linked to behavioural change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prevalence studies conducted throughout the world (Calado et al. 2016; Volberg et al. 2010) suggest that, in spite of legal restrictions, gambling is, and constantly has been, a popular activity among adolescents. Moreover, it seems that gambling is seen as a normal non-risk activity, leading adolescents to frequently engage in this behavior with parents, siblings and other family members (Derevensky and Gilbeau 2015). Prevalence rates of youth problem gambling are consistently reported to be between 4 and 8%, with another 10–15% of youth being at-risk for the development of serious gambling problems (Derevensky and Gilbeau 2015; Jacobs 2004; Derevensky and Gupta 2000; Shaffer and Hall 1996). The numbers are similar in all parts of the world—US, Canada, Australia, Western Europe, Central Europe, Eastern Europe (see Volberg et al. 2010 for details), regardless of the differences in the regulation of gambling markets. Youth problem gambling presents an important issue, since early onset of gambling in childhood and adolescence is a potential risk factor for a variety of health (especially mental health), social and financial problems in adulthood (Carbonneau et al. 2015; Delfabbro et al. 2014; Derevensky et al. 2006; Rahman et al. 2012).

Furthermore, these numbers are consistently higher than those for adult gambling addiction (Griffiths 1995; Shaffer et al. 1997; Nower et al. 2004). This is mostly because developmental characteristics make adolescents especially vulnerable to negative effects of engaging in risk behaviors, including gambling activities, as well as negative consequences of those behaviors. Adolescents believe that they can control their behavior and that they are invincible and invulnerable (St-Pierre et al. 2015). Their capacity for critical thinking, although developing, is still limited. They focus on short-term instead on long-term consequences of their behavior, so they continuously walk the thin line between healthy and harmful risk taking (Igra and Irwin 1996; Dickson et al. 2004; Steinberg 2008). All this is coupled with their non-critical receptivity to social influences (Rivers et al. 2008; Casey et al. 2008). Therefore, prevention efforts have been widely advocated as one of the necessary paths in addressing the issue of youth gambling.

However, there is a lack of published research on the development, implementation and evaluation of original prevention programs, with very little solid evidence on the effectiveness of these programs (St-Pierre and Derevensky 2016). In this paper we extend the available literature, and present an original youth gambling prevention program developed in Croatia, as well as its effectiveness evaluation. Croatia is a central/eastern European country with a paucity of gambling research. Also, Croatia represents a specifically interesting context with its liberal gambling market and high availability and accessibility of gambling (Ricijas and Dodig 2014). In spite the fact that gambling is illegal for minors (adolescents under 18 years of age), Croatian prevalence studies show high levels of adolescent gambling participation (Ricijas et al. 2016b). Moreover, Croatian research shows extremely high rates of youth problem gambling, with up to 12% of adolescents with high levels of psychosocial consequences related to gambling, and an additional 18% of youth with low to moderate level of consequences (Dodig 2013a; Ricijas et al. 2016b). These high rates are alarming, and call for the development and implementation of effective interventions.

Youth Gambling Prevention

Youth gambling prevention has been grounded in widely recognized theoretical models and postulates of prevention science, and has been rapidly developing in the past years (Ariyabuddhiphongs 2013; Evans 2003; St-Pierre and Derevensky 2016). A public health approach, advocated by many as a suitable framework for prevention science (Eddy et al. 2002; Domitrovich et al. 2010) has also been successfully applied to youth gambling prevention (Messerlian et al. 2005; St-Pierre and Derevensky 2016). One of the broadly accepted conceptualizations of youth problem gambling and consequently youth gambling prevention has been the Dickson’s model (Dickson et al. 2002, 2004), built upon Jessor’s problem behavior theory (Jessor 1987). This model is recognized in literature (Dickson-Gillespie et al. 2008) as a useful framework for the development of effective, science-based prevention initiatives aimed at minimizing problem gambling among youth. The model assumes that unique and common risk and protective factors persist for different types of problem behaviors, and are the same across domains of different types of adolescents’ risk behavior. Some of the most common are (Derevensky et al. 2006): (1) biology—e.g. high intelligence, family history of alcoholism; (2) social environment—e.g. poverty, quality of schools, (3) perceived environment—e.g. role models for deviant behavior, family cohesion, (4) personality—e.g. low self-esteem, low value of health and (5) behavior—e.g. problem drinking, involvement in school. Model includes risk and protective factors identified in empirical research and therefore provides flexibility and opportunity to be upgraded with contemporary research findings.

Together with common risk and protective factors for adolescents’ general risk behavior, unique factors for youth gambling problems are also incorporated in the Dickson’s model (Dickson et al. 2002, 2004)—poor coping skills, depression and anxiety, erroneous beliefs and gambling fallacies, increased sensation seeking, early initiation in gambling (often with family members, especially fathers), greater accessibility and availability of gambling to minors, replacement of friends with gambling associates, etc. (Griffiths and Wood 2000; Vitaro et al. 2001; Hardoon et al. 2004; Williams et al. 2012). The comprehensive nature of the presented Dickson’s model, its solid background in prevention literature and applicability for prevention practice makes it a reasonable theoretical background for the development of original youth gambling prevention programs.

Types of Youth Gambling Prevention

Derevensky et al. (2006) highlight two general paradigms under which youth gambling prevention programs can be classified—abstinence and harm reduction. With respect to age of target group, most adult prevention efforts are aimed at harm reduction. They include adult gamblers, gambling industry and gambling markets and the implementation of a prevention model of responsible gambling which has been widely investigated and used (Ariyabuddhiphongs 2013). With respect to adolescents, most gambling programs are implemented in schools and include both abstinence and harm reduction elements. St-Pierre and Derevensky (2016) classified the school-based gambling-specific prevention programs into two broad categories: (1) psychoeducational prevention programs and (2) comprehensive psychoeducational and skills training prevention programs. Prevention programs from both categories share goals referring to increasing awareness or knowledge about gambling and issues related to gambling, inclusive of the nature of gambling, gaming odds and probabilities, erroneous cognitions and gambling fallacies, warning signs of problem gambling and consequences related to problem gambling. The second group of prevention programs includes a broader scope of themes including self-esteem, interpersonal and coping skills, problem-solving, decision-making and refusal skills. As such they incorporate not only youth problem gambling risk and protective factors, but also general risk and protective factors for adolescent risk behavior.

Existing prevention programs are mostly classified as universal prevention programs—aimed at general population with no significant risks—and most of them fall into the category of psychoeducational school-based prevention programs. The vast majority of prevention programs in the field focus on the cognitive component (e.g. knowledge, attitudes, normative beliefs, misconceptions/erroneous cognition in general and related to gambling) (Donati et al. 2014; Taylor and Hillyard 2009; Ferland et al. 2002). Some of them incorporate inter- and intrapersonal skills and focus on general prevention of risk behavior (e.g. problem-solving, decision-making, coping skills, refusal skills, social-emotional skills) (Todirita and Lupu 2013). However, only a few are comprised of both components (Gray et al. 2007; Williams et al. 2012; St-Pierre and Derevensky 2016).

Research evidence about the effectiveness of prevention programs that focus only on the cognitive component show a significant change of correct knowledge and misconceptions about gambling (Donati et al. 2014; Taylor and Hillyard 2009; Ferland et al. 2002), especially for younger students and boys (Taylor and Hillyard 2009). However, there is only limited effect for at-risk/problem gamblers (Donati et al. 2014), and only a few programs reported sustainable (long-term) effects or changes in gambling behavior (Donati et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2010). Many authors (Williams et al. 2012; Wulfert et al. 2003) are questioning the effects of programs based on statistical and mathematical knowledge with weak evidence of their success in behavioral change. Williams et al. (2012) argue that it is possible that researchers have been focused on wrong types of knowledge and that focusing on gambling fallacies may be more productive than efforts focused on improved understanding of probability.

School-based universal interventions that, along with the cognitive component, involved inter- and intrapersonal skills also show improvements in knowledge about gambling and risks of gambling (Todirita and Lupu 2013) as well as in skills, mostly problem-solving and decision-making (Turner et al. 2008), as well as coping skills (Williams et al. 2010). Unfortunately, peer resistance skills are rarely examined in gambling specific prevention programs. However, in other risk behavior prevention programs (e.g. alcohol and drug use) refusal skills showed noteworthy potential (Allami and Vitaro 2015).

It is noticeable that a very limited number of studies incorporated inter- and intrapersonal skills measures in evaluation design of gambling-specific prevention programs. Systematic reviews showed that programs with both components—knowledge and skills—documented positive effects on behavior change as well, but still to very limited and questionable extent due to lack of long-term follow-up or longitudinal research (Ladouceur et al. 2013; Keen et al. 2016). The conclusion on youth gambling prevention programs effectiveness can be drawn from Williams et al. (2012) work that clearly points out the necessity of comprehensive programs with a broad scope of topics that include statistical knowledge about gambling, providing information on the potentially addictive nature of gambling, explaining gambling fallacies, building self-esteem, and peer resistance training.

Together with the development and implementation of youth gambling prevention programs, researchers and practitioners are encouraged to engage in rigorous evaluation. Outcome evaluation is strongly recommended in order to develop a solid pool of evidence-based programs, but moreover, it is necessary in order to gain insight into all possible outcomes—positive, neutral or even negative. More and more researchers (Faggiano et al. 2014; Valente et al. 2007; Moos 2005; Werch and Owen 2002) strongly emphasize the potential iatrogenic effects that can arise from psychosocial interventions and prevention programs (e.g., more interest/desire for risk behavior after program participation resulting in increased risk behavior). Given this observation, it is of particular relevance that both practitioners and researchers develop and plan their prevention programs carefully, and then monitor and evaluate the outcomes of their programs. This kind of responsible approach to the implementation of prevention programs and principles is recognized under the term ethical prevention (Brotherhood and Sumnall 2011). Noteworthy, no studies that examine possible iatrogenic effects of prevention programs on gambling behavior can be found.

Likewise, there is also very limited evidence of actual behavior change (Gray et al. 2007; Williams et al. 2012; Walther et al. 2012; St-Pierre and Derevensky 2016). However, this is a very controversial issue. Since most prevention programs are universal it means they are targeted at a population in which a vast majority of program participants are in low risk for problem behavior (Hale et al. 2014; Stoolmiler et al. 2000). This characteristic of universal/general population prevention programs makes it unrealistic to expect behavior change. It is also questionable whether significant and sustainable behavior change can be measured and observed when investigating short-term prevention effectiveness. These kind of changes usually take time, as well as opportunity to test newly acquired knowledge and skills in the real world (Faggiano et al. 2014; Dodge et al. 2013; Uhl et al. 2010; Shamblen and Derzon 2009). In other words, longitudinal studies and frequent follow ups are needed in order to observe true behavior change.

Moreover, observing significant behavior change is not the only goal of prevention science and effective prevention programs. A sole focus on behavioral outcomes does not provide any information about the so called active ingredients of the programs. That is why it is important to investigate whether the program decreases risk and increases protective factors. This can inform further prevention program development, and pave the way for evidence-based prevention efforts (Faggiano et al. 2014). Also, several systematic reviews of prevention program effectiveness show that in the long run, programs showing change in risk and protective factors, and generic skills are more successful than programs just showing behavior change (Foxcroft and Tsertsvadze 2012; WHO 2004). Even further, research on the impact of prevention efforts show that programs which increase protective and decrease risk factors have outcomes that extend from a problem behavior in question to long term health effects, increasing long term health protective behaviors, which all leads to financial sustainability of investing in prevention programs aimed at risk/protective factors in general, and not just behavior change (Caulkins et al. 2004; Hawkins et al. 2015).

Also, although most published school based prevention efforts are intended to be universal prevention programs, there is not much research evidence of true universality (is the program equally efficient and suitable for everyone?). For example, one study found no gender differences in the effectiveness of a youth gambling prevention program, but did find larger short term effects among primary school children, than among high-school students (Taylor and Hillyard 2009). An Italian study found larger effects for students who are at risk/problem gamblers then for students without gambling related problems (Donati et al. 2014). Moreover, as we already mentioned, the majority of the available prevention programs are based on the cognitive component, so it is possible that the program is only efficient for students with a higher aptitude for learning. This alternative explanation for program effectiveness can even be extended to prevention programs that include inter- and intrapersonal skills training, since they too are based on learning new information and skills. However, we were not able to find any published research on prevention program effectiveness that takes students learning aptitude into consideration. Hence, in this study we aim to provide some answers to less explored research questions and address some of the mentioned topics.

Present Study

The main goal of this study is to present an original Croatian youth gambling prevention program that was developed in accordance with the theoretical principles of prevention science and already established effective youth gambling prevention efforts. Our aim was to test short-term effects of this program designed to target both risk and protective factors associated with adolescent gambling and general risk behavior. In other words, we sought to diminish risk factors and enhance protective factors. Firstly, we wanted to enhance correct knowledge about gambling (protective factor) and its consequences and to modify erroneous beliefs about gambling related to illusions of control, superstitious thinking and probabilistic reasoning (risk factors). As described earlier, poor knowledge and erroneous beliefs are all associated with more frequent gambling and riskier gambling, and more adverse consequences (St-Pierre et al. 2015). We hypothesized that our program activities will enhance correct knowledge about gambling and its consequences, and diminish different kinds of cognitive distortions—illusion of control based on knowledge and skill, superstitious thinking and probabilistic reasoning.

Secondly, we wanted to enhance protective factors that are proven to be related to positive developmental outcomes and lower frequency of adolescent risky behavior in general (Cordova et al. 2014; Catalano et al. 2012; Durlak et al. 2011; Domitrovich et al. 2010; Greenberg et al. 2003), such as critical thinking and problem solving skills, resistance to peer pressure and self-efficacy. Since these skills usually express themselves in specific contexts and social situations, and are seen as long-term protective factors, we did not expect our program to show short-term effects with regard to these particular protective factors.

Thirdly, we examined effects of target population and checked whether short-term program effects are the same for different subgroups of students, namely if they differ with regard to gender and school study program (general vs. vocational), as well as for students who already manifest adverse psychosocial consequences because of their gambling activities, in comparison to students who do not. Since the program was developed as a universal prevention program aimed at the whole population of high-school students, we did not expect any of the mentioned target population characteristics to be significant moderators of the program’s efficiency.

One possible alternative explanation for the effects of previous prevention programs and their high efficiency with regard to increased knowledge and diminished cognitive distortions is that it is efficient only among students with a high aptitude for learning. In order to be sure that our results cannot be attributed to differences in learning aptitude, we examined whether students’ grades (as a formal index of their learning aptitude) moderate the outcomes of the program. As we already mentioned, we believe that our program is universal, so we did not expect any differences with regard to student’s grades.

Fourth, since many studies in the field of substance (ab)use prevention showed prevention programs to have possible iatrogenic effects, actually increasing curiosity for the behavior in question and increasing the frequency of the behavior (Werch and Owen 2002; Moos 2005; Valente et al. 2007), we examined whether our program had such effects. We hypothesized that our program was well balanced and that it will produce the desired short-term effects (diminish the risk factors and increase the protective factors) without increasing the frequency of gambling behavior. As discussed before, we did not expect behavioral changes regarding gambling activities because of the universal nature of implemented prevention program. Therefore we tested behavior change in the opposite direction to determine whether we can exclude possible iatrogenic effects of the implemented program.

Method

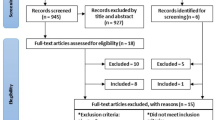

Study Design and Procedure

We used an experimental design with two groups (Training vs. No Training) and two measurement sessions (pre-test and post-test sessions) to test the efficacy of the youth gambling prevention program “Who really wins?”. Classes were randomly assigned to groups. The Training group filled the pre-test questionnaires at the beginning of the first training activity, received the training activities, and then filled out the same instruments at the end of the last training activity (post-test). The No Training group only filled out the pre-test and post-test questionnaires (within the same week as the Training group). While the Training group was receiving the intervention, the No Training group was doing their regular school activities. In both pre-test and post-test sessions the questionnaires were administered within the classroom. Teachers were not present during this time. Students were given lengthy instructions and were required to work individually. A researcher was present to answer any questions and aid in the administration of the questionnaires. Administration of the instruments lasted approximately 20 min.

Content and structure of the program was previously evaluated and given official support by the Croatian Education and Teacher Training Agency and ethical approval by the Ethical Committee (University of Zagreb, Faculty of Education and Rehabilitation Sciences). All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional ethical committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Since all of the students were 14 and older, they were personally informed about the program and invited to participate (oral informed consent was obtained). Also, their parents were briefed on the program and its goals in detail and asked to allow their children to participate. There were no objections by the parents, and all invited students agreed to participate in the study.

Intervention

“Who really wins?” is an universal prevention program of adolescent gambling, aimed at adolescents from 14 to 16 years of age. The intervention comprised of 6 didactic units of 90 min each, implemented in class, during regular school time. The first and last unit included pre-test and post-test questionnaires. More details about the program can be found in Table 1. Implementation of the program was facilitated by detailed intervention protocols, and conducted by two experts in adolescent gambling and school interventions. Teachers or other school staff were not present during the administration of the training program. Process evaluation insured high fidelity in program implementation. Using two trainers to implement the program allowed one trainer to focus on specific training activities and the other to focus on process aspects of the implementation, e.g. students’ motivation and involvement in the activities.

We used a plethora of methods to deliver the activities to the students: (a) questionnaires, quizzes, worksheets etc.; (b) games and exercises as warm-up activities, to enhance group cohesiveness and as evocation of previously learned content; (c) creative techniques—making posters, creating slogans and stories; (d) interactive methods such as role playing, live discussions, real-life situations in which students can practice newly learned skills; (e) encouragement of critical thinking, especially with regard to social influences; (f) team learning—in pairs, threes, small groups, presenting work in front of the class; panel discussions; (g) examples from life-real situations that closely mirror possible adolescent life situations; (h) relationship and positive atmosphere building so that adolescents could feel safe to discuss topics related to training activities.

Participants

A total of 190 first and second year high-school students (67.6% boys, aged 14–17 years; average age 15.61) enrolled in two public high schools in Zagreb, the capital of Croatia, participated in the study. Both schools were randomly selected from the available schools in the city, one from the list of general education high school programs, and one from vocational high school study programs. Both schools were contacted and appraised of the program, and agreed to participate. Two first grade and two second grade classes, randomly divided between the Training and No Training groups, participated in each school. We found no significant differences in socio-demographic characteristics between the Training and No Training group (see Table 2).

Measures

Knowledge about gambling/betting was assessed by 20 statements to which a student could answer “right”; “wrong” or “I don’t know”. Content-wise, statements consisted of knowledge about various kinds of gambling activities (e.g. “Playing cards with family/friends for money is a form of gambling”), odds and probabilities (e.g. “If something is a chance event, that means that we cannot predict this event”), and about consequences of gambling (e.g. “Only those who gamble every day can get addicted to gambling”). A total result is computed as a number of correct answers, with a higher result indicating better knowledge about gambling/betting. The test seems to have been of average difficulty for the students—item difficulty indices range from .15 to .94 with the average p = .57.

Cognitive distortions related to gambling/betting were assessed by the Cognitive beliefs scale (Ricijas et al. 2011). This questionnaire was previously validated in large Croatian national studies with high-school students (Dodig 2013a; Ricijas et al. 2016b). The questionnaire consists of two dimensions—(1) Illusion of control based on knowledge and skills (5 items). E.g. „To make money gambling one needs a good gaming system“; and (2) probabilistic reasoning and superstitious thinking (9 items). E.g. “If a person has been on a losing streak, there’s a better chance for them to start winning soon”; “Focusing my thoughts on winning increases its odds”. Reliability information can be found in Table 3.

Problem solving skills were assessed by a short (5 items) scale constructed for this study. For each item students needed to answer how they usually handled problem situations in life (e.g. “When I have a problem, I try to look at it from different viewpoints and think of different possible solutions”). Answers were given on a five-point scale from never to almost always. Content-wise, the items covered all the steps for efficient problem solving (Merrell et al. 2012). The scale showed satisfactory reliability (see Table 3). We performed exploratory factor analysis in order to assess the scale’s factor structure. KMO (pre-test = .774; post-test = .798) and Bartlet’s test of sphericity (pre-test—χ2 = 148.56; p < .0001; post-test—χ2 = 299.58; p < .0001) indicated the data are appropriate for factor analysis. In both pre-test and post-tests, using the principal component method, we extracted one component with the eigenvalue higher than 1. Scree plots also indicated a unidimensional solution. One component explained 46% of total variance in the pre-test (saturations ranging from .475 to .760), and 58% of the total variance in the post-test (saturations ranging from .584 to .873). Given the high internal consistency and unidimensional structure, an average score was used as an indicator of problem solving skills. Higher results indicate better problem solving skills.

Resistance to peer pressure skills were assessed by a short (5 items) scale constructed for this study. For each item students needed to answer how they usually handled peer pressure situations (e.g. “When somebody is trying to persuade me to do something I do not want to do, I know which is the best way to say no without offending/angering the other person”). Answers are given on a five-point scale from never to almost always. Again, we performed exploratory factor analysis in order to assess the scale’s factor structure. KMO (pre-test = .611; post-test = .701) and Bartlet’s test of sphericity (pre-test—χ2 = 87.02; p < .0001; post-test—χ2 = 116.11; p < .0001) indicated the data are appropriate for analysis. In both pre-test and post-tests, using the principal component method, we extracted one component with the eigenvalue higher than 1. Scree plots also indicated a unidimensional solution. One component explained 36% of total variance in the pre-test (saturations ranging from .358 to .788), and 58% of the total variance in the post-test (saturations ranging from .108 to .759). Reliabilities (see Table 3) were very moderate in both testing sessions. However, given the stable reliability confidence intervals in both testing sessions, relatively high item-total correlations and the unidimensional structure an average score was used as an indicator of resistance to peer pressure skills. Higher results indicate better skills.

Self-efficacy was assessed with the Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995). The instrument has been used and validated extensively on both adults and adolescents. The scale has 10 items and measures a general sense of perceived self-efficacy and beliefs that one can perform novel or difficult tasks, or cope with adversity in various domains of human functioning (e.g. „I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough“). Responses for each item ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (completely true). The composite score is calculated as an average score on all items. Higher results indicate higher perceived generalized self-efficacy. The scale has high internal consistency (see Table 3).

Gambling activities were assessed with questions about the frequency of playing 5 different gambling/betting activities—sport betting, virtual racing betting, slot machines, lotto and scratch cards. These five activities were chosen, based on the results of the aforementioned national adolescent gambling prevalence study, as the most frequent among high-school students (Dodig 2013b; Ricijas et al. 2011). To get estimates of life-time prevalence, students first indicated how often they played each game (never—once a year or less—a couple of times a year—around 1–2 times a month—around once a week—a couple of times a week—every day). To get estimates of their recent gambling/betting behavior, they indicated, again for each of the games, how often they played it during the last 2 months (not once—once or twice—around 1–2 times a month—around once a week—a couple of times a week—every day). We also asked how old they were when they first played these gambling/betting activities.

Problem gambling was assessed with the Canadian Adolescent Gambling Inventory (CAGI; Tremblay et al. 2010). This instrument is a screening tool for at risk adolescent gamblers that measures the seriousness of consequences related to gambling/betting. It was validated for use on Croatian adolescents in previous national prevalence studies (Dodig 2013a; Ricijas et al. 2016b). In this study we administered only the 9 items (GPSS—General Problem Severity Subscale) which are a base for categorizing adolescents into three risk categories—«green light» (no gambling-related problems), «yellow light» (low to moderate gambling-related problems) and «red light» (serious gambling-related problems). Students indicated, on a 4 point scale (never—sometimes—most of the time—almost always), how often they felt a certain consequence of their gambling/betting activities (e.g. “How often have you skipped your free time activities (e.g. sport, music etc.) to go gambling/betting?”; “How often did you go back the next day to try and win back the money you lost gambling/betting?”). Reliability information is presented in Table 3. Higher results indicate more severe gambling problems/more adverse gambling consequences.

Results

Baseline Data

As a first step in our analyses, using an independent-sample t test, we examined whether the Training and the No Training group differ with respect to their gambling activities both during the 2 months prior to study, and in general (life-time), age when they first started gambling and the severity of adverse gambling related consequences. As can been seen from Table 4, there were no significant differences in the frequency of gambling/betting during 2 months prior to testing for any of the gambling/betting games. Also, there were no significant differences between the Training and No Training group with respect to life-time prevalence of their gambling activities, neither for sport betting (t = 1.128, n.s.), nor for lotto (t = 0.270, n.s.), scratch cards (t = 0.227, n.s.), slot machines (t = 1.310, n.s.), or virtual race betting (t = 0.630, n.s.). Moreover, they also did not differ with respect to the age when they first started gambling/betting (t-test for various activities ranged from 0.245 to 1.869, all n.s.).

There were also no significant differences between the Training and No Training group with respect to their problem gambling (see Table 4). In both groups the majority of the sample were non-problematic gamblers (85% in the Training and 86% in the No Training group), with 15% in the Training group and 14% in the No Training group being at-risk gamblers. No one exhibited severe gambling related consequences, in either group.

Next we examined the differences between the Training and the No Training group in their knowledge about gambling/betting, the cognitive distortions related to gambling activities, their problem solving and peer pressure skills and their perception of generalized self-efficacy prior to the program implementation. We found no significant differences between the two groups as measured in the pre-test session (see Table 4).

The results show that high-school students do gamble, start to play different games in their early teens, and that they are already at risk to become problem gamblers. Also, students’ knowledge about gambling and its consequences is not extremely high, and they have cognitive distortions related to gambling. They believe that good skills and knowledge about gaming will help them be better gamblers (illusion of control), and they do not have good probabilistic reasoning. They also harbor superstitious beliefs about gambling/betting. All this means that students are in need for interventions aimed at correcting their incorrect beliefs and myths. Their perceived skills of resistance to peer pressure, problem solving and their general sense of self-efficacy are relatively high, which is not surprising given these were measured via self-report measures. However, even their subjective perception is not extraordinarily high, which means there is room for improvement.

Short-Term Efficacy Evaluation

Changes in Levels of Risk and Protective Factors

We investigated the short-term efficacy of our program by conducting a Repeated Measures 2 × 2 ANOVA with time (pre- and post-test) as within factor and group (Training and No Training) as between factor for each dependent variable. The main effect of interest was the Time × Group interaction.

An efficient prevention program should reduce the risk factors associated with the behavior in question. So we checked whether our program managed to reduce the cognitive distortions related to gambling and increase knowledge about gambling and its consequences. In support of our hypotheses we found significant Time × Group interaction effects for correct knowledge about gambling/betting [F(1,135) = 33.703, MSE = 4.640, p < .001], cognitive distortions—illusion of control [F(1,140) = 5.795, MSE = 0.302, p < .05] and cognitive distortions—probabilistic reasoning and superstitious thinking (F(1,141) = 4.748, MSE = 0.236, p < .05). Table 5 shows average group results and post hoc paired t-tests that show the interaction effects are due to significant changes from pre- to post-test in the Training group, but not in the No Training group. The program had the largest effect for correct knowledge about gambling and its consequences (d = 0.89), a medium to large effect for cognitive distortions related to illusion of control (d = 0.46), and a medium effect for cognitive distortions related to probabilistic reasoning and superstitious thinking (d = 0.28).

The other aim of our prevention program was to strengthen the protective factors associated with any risky adolescent behavior. So we checked whether our program managed to strengthen the perception of generalized self-efficacy, problem solving skills and skills related to resistance to peer pressure. In accordance with our hypotheses, we lack support for the program’s efficiency in these domains, as measured at the end of training activities. The Time × Group interaction effect was significant for generalized self-efficacy [F(1,137) = 4.008, MSE = 0.167, p < .05], and not significant for problem solving skills [F(1,137) = 3.253, MSE = 0.268, n.s.], nor peer pressure skills [F(1,139) = 1.237, MSE = 0.168, n.s.]. However, post hoc paired t-tests show no significant differences for generalized self-efficacy (see Table 5).

Effects of Target Population

First we examined whether our program effects differ between girls and boys. We conducted a Repeated Measures 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVA with Time (pre- and post-test) as within factor and Group (Training and No Training) and Gender (Boys and Girls) as between groups factors for each dependent variable. The main effect of interest was the Time × Group × Gender interaction. There were no significant three-way interactions for any of the variables (F correct knowledge about gambling = 1.426, n.s.; F illusion of control = 0.624, n.s.; F probabilistic reasoning and superstition = 1.645, n.s.; F problem solving = 0.835, n.s.; F peer pressure = 1.475, n.s.; F self-efficacy = 0.617, n.s.). No significant interactions indicate that the program’s short-term effects do not differ with regard to students’ gender.

Second we examined differences between types of school. Similarly, we conducted a Repeated Measures 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVA with Time (pre- and post-test) as within factor and Group (Training and No Training) and School (General and Vocational) as between groups factors for each dependent variable. The main effect of interest was the Time × Group × School interaction. There were no significant three-way interactions for any of the variables (F correct knowledge about gambling = 0.002, n.s.; F illusion of control = 2.283, n.s.; F probabilistic reasoning and superstition = 1.503, n.s.; F problem solving = 0.297, n.s.; F peer pressure = 0.070, n.s.; F self-efficacy = 0.254, n.s.). No significant interactions indicate that the program’s short-term effects do not differ with regard to the high-school program students attend.

We performed another Repeated Measures 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVA with Time (pre- and post-test) as within factor and Group (Training and No Training) and Problem Gambling (no problems vs. at risk/problem gamblers) as between groups factors for each dependent variable in order to examine whether the effects of the program differ among non-problematic gamblers and at-risk gamblers. Again, the main effect of interest was the Time × Group × Problem Gambling interaction. There were no significant three-way interactions for any of the variables (F correct knowledge about gambling = 0.090, n.s.; F illusion of control = 0.202, n.s.; F probabilistic reasoning and superstition = 2.410, n.s.; F problem solving = 0.092, n.s.; F peer pressure = 1.544, n.s.; F self-efficacy = 0.010, n.s.). No significant interactions indicate that the program’s short-term effects do not differ among students who already developed some problems because of their gambling, and those who did not.

Individual Differences in Learning Aptitude

In order to exclude the differences in learning aptitude as an alternative explanation of our results we first divided our sample according to school grades in two categories—those with good grades (combining grades “excellent” and “very good”) and those with poor grades (combining grades “fair” and “good”). Approximately a third (33.9%) of students had poor grades, and two thirds (66.1%) had good grades. Then we conducted a Repeated Measures 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVA with Time (pre- and post-test) as within factor and Group (Training and No Training) and School Grades (poor vs. good) as between groups factors for each dependent variable. The main effect of interest was the Time × Group × School Grades interaction. There were no significant three-way interactions for any of the variables (F correct knowledge about gambling = 0.455, n.s.; F illusion of control = 0.320, n.s.; F probabilistic reasoning and superstition = 3.181, n.s.; F problem solving = 0.134, n.s.; F peer pressure = 3.653, n.s.; F self-efficacy = 0.001, n.s.). No significant interactions indicate that the program’s short-term effects do not differ with regard to the school grades, and that students’ learning aptitude is not a significant moderator of the results.

Effects on Gambling Frequency

In order to test for the program’s possible iatrogenic effects we conducted a Repeated Measures 2 × 2 ANOVA with Time (pre- and post-test) as within factor and Group (Training and No Training) as between groups factors for students recent gambling behavior (recall that they responded about their gambling behavior for the period of 2 months prior to testing). Again the main effect of interest was the Time × Group interaction. We found no significant interactions, neither for individual gambling activities (F sport betting = 0.913, n.s.; F virtual races = 0.377, n.s.; F slot machines = 3.373, n.s.; F loto = 0.389, n.s.; F scractch cards = 2.567, n.s.), nor for total gambling activities (F = 0.142, n.s.). The frequency of gambling did not change in the experimental group as a result of our program.

Discussion

As previously stated, the Croatian youth gambling prevention program presented in this paper is an universal prevention program aimed at minimizing risk and enhancing the protective factors related to youth risky behavior in general and to youth gambling in particular such as (1) knowledge about risky nature of gambling and mathematics of gambling, (2) cognitive misconceptions and critical thinking, as well as (3) intra- and interpersonal social skills (problem solving, decision making, self-efficacy, and peer pressure resistance).

The youth gambling prevention program “Who really wins?” meets the key principles related to development and implementation of effective interventions aimed at adolescents’ risky behavior prevention (Nation et al. 2003). Effective prevention interventions are based on properly addressed common and behavior-specific risk and protective factors, but also on the quality and adequacy of program content and teaching methods, modality of delivery and overall program implementation (Chen 1998; Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick 2007). In accordance to existing efficient prevention guidelines, the program: (1) takes into account the specific developmental characteristics and needs of target population defined in terms of risk and protective factors, (2) involves a variety of teaching methods adequate for appointed achievable goals and learning outcomes as well as implementation setting (classroom), (3) considers the social and cultural context of Croatian society labeled with favorable attitudes toward gambling and sports betting, (4) involves trained staff for program implementation and (5) involves outcome and process evaluation.

According to our expectations, outcome evaluation showed that risk factors related to knowledge about gambling and cognitive distortions related to gambling activities were decreased after the program, which is in line with available published evaluation studies (St-Pierre and Derevensky 2016). A number of studies emphasize the importance of adolescent development and social cognition postulates (Rivers et al. 2008; Casey et al. 2008) pointing out critical thinking and correct knowledge as important mechanisms underlying adolescents’ risky behavior (Dickson et al. 2004; Steinberg 2008; Scott and Steinberg 2008). Adolescents tend to focus on short-term consequences and consider only partial information which might lead them to perceive risk behavior as less serious and less harmful for their health and well-being (Scott and Grisso 2005). So focusing students’ attention on long-term consequences of gambling, as well as giving them full and correct information, and providing them with critical thinking skills is largely beneficial.

A specific characteristic of our study is a comprehensive approach to the investigation of cognitive distortions that were measured in all forms—illusion of control, probabilistic reasoning and superstitious thinking. The results showed improvement in all three types of distortions, as well as in the domain of correct knowledge that covered a variety of information—mathematical/statistical knowledge, information about the risky nature of gambling, risks and consequences of gambling and gambling industry roles and rules. Largest effect was detected in correct knowledge about gambling and its consequences, probably because this was an area which had most room for improvement at the beginning of the program.

Regarding effects of protective factors, the “Who really wins?” program did not manage to obtain evidence of enhancement in problem solving skills, refusal skills and general self-efficacy. This was expected since effects of this sort of skill training are not likely to be recorded in short-term evaluation, and are only observable in studies with long-term outcomes evaluation (St-Pierre and Derevensky 2016; Donati et al. 2014). More precisely, measuring behavior or skills outcomes immediately after a program’s implementation is not recommended (Uhl et al. 2010). The reason for this can be found in the nature of behavior change, which comprises of several phases and needs time for a “reality-check” by program participants through testing the potential benefits of using learned skills/behavior in real-life settings (Dodge et al. 2013). However, regardless of the fact that our program does not lead to skill enhancement in the short run, it would be wrong to conclude that one should not incorporate inter- and intrapersonal skill training in youth gambling prevention programs. There are studies showing prevention programs incorporating problem-solving and decision-making skills (Turner et al. 2008), as well as coping skills (Williams et al. 2010) to be effective. The same is true for peer pressure resistance skills, at least when it comes to adolescent substance abuse (Allami and Vitaro 2015). Given the important protective role of these sorts of skills for adolescent risk behavior in general, programs should incorporate skills development in prevention curricula.

As expected, we also did not observe any significant short-term behavior change with respect to gambling frequency. However, because behavior change requires time to become evident and because our target population mostly comprised of students low at risk for gambling problems we did not really expect to observe a decrease in gambling activity. Also, this does not mean that our program is not efficient. Some studies showed no behavioral changes right after program implementation. However, in spite of this, long-term behavior change was still documented (Williams et al. 2010). So it is necessary to investigate program effects in long-term evaluation.

On the other hand, the same non-significant differences speak in favor of our program’s efficiency, because they show that our program did not have any iatrogenic effects on behavior change (Faggiano et al. 2014; Valente et al. 2007; Moos 2005). Studies show that programs focused on providing information on risky behavior, such as our program, can encourage curiosity for problem behavior (Botvin and Griffin 2007). This is an important issue, and to our knowledge, this is a first study that examined the possibility of such potential effects of youth gambling prevention programs. Future studies should examine possible iatrogenic effects of the developed programs.

The fact that we only performed short-term evaluation, without any follow ups, which then constrained us from showing behavior or skill changes is a limitation of this study. However, long-term evaluation was not part of the evaluation design in this stage of the “Who really wins?” program development for several reasons. Some authors in the field (Greenberg et al. 2003; Dariotis et al. 2008) suggest that a program has to be implemented and evaluated in its final form for up to several years. It also needs to show consistent positive evaluation results in order to find it science-based/evidence-based and be sure of its efficiency. This means that the program has to move from its pilot phase into its final phase before long-term evaluation is feasible. Since our program “Who really wins?” was still in the beginning phases of development, we concentrated on short-term evaluation to inform us on its efficiency. Furthermore, we also focused on process evaluation as well as outcome evaluation, in order to obtain valuable results and guidelines for program improvement. The process evaluation was conducted in the form of monitoring implementation fidelity, dosage, participants’ satisfaction and self-perceived benefits from the program participation. Results showed successful program implementation and provided useful guidelines for further program development (Ricijas et al. 2013). Of course, future studies should investigate long-term effects of the “Who really wins?” youth gambling prevention program, before drawing conclusions about the transfer of learning to actual gambling behavior or learning retention over time (Ladouceur et al. 2013).

Our findings also speak in favor of the universality and wide applicability of our prevention program. We took care to examine whether our program works the same for different target populations. We found the effects of the program to be the same for girls and boys, students form different types of high-school programs (general and vocational), students who already experience adverse consequences because of their gambling and those who have no consequences/do not gamble at all. It was important to examine effects of these variables, since some research showed larger effects of prevention programs for at risk populations (Shamblen and Derzon 2009; Donati et al. 2014). Also, factors such as gender and type of school program have been found to contribute to adolescent problem gambling (Ricijas et al. 2016a). Moreover, by showing that the program effects are the same for those with different learning aptitudes (operationalized via school grades), we excluded potential alternative explanations of our results.

Our study has several other limitations. Both the Training and the No Training group had small sample sizes given that only two schools were involved in the study. Moreover, not all of the students were present during both pre-test and post-test sessions leading to even smaller samples which could have influenced difference testing. However, we did try to address this limitation by including different types of high-school programs (both general education and vocational schools). Moreover, we took care for our sample size to be adequate for statistical analyses used in the paper. Furthermore, the sample size is similar to other evaluation studies of youth gambling prevention (Donati et al. 2014; Todirita and Lupu 2013; Gray et al. 2007).

Second, some of the instruments used in the study—namely the problem solving skills scale and the resistance to peer pressure scale were constructed for the purposes of this study, and thus, not previously validated. The same goes for questions used to assess knowledge about gambling/betting. The resistance to peer pressure scale was the most problematic, showing only moderate reliability levels, and fluctuations in factor saturations between pre-test and post-test session, all of which question its validity. Unfortunately, we were not able to find any available short and reliable instruments that have been extensively validated. However, we did base our instruments on the available literature, and tried to examine the factor structure of the two scales in order to provide at least some basic data on their validity. Also, measuring problem solving skills and peer resistance with self-reports is hardly the ideal way given the behavioral nature of these constructs, and adolescents’ uncritical view of self and their skills. The field of youth gambling prevention research would benefit greatly from a standardized, validated set of measures to examine the common risk and protective factors proposed by the Dickson’s model (Dickson et al. 2002, 2004).

In addition to investigating long-term effects of our program, future studies should also examine possible additional moderators of the programs efficacy, such as a wider age range and problem gambling behavior. Also, future studies could examine potential alternative explanations for the effects of the program, such as socio-economic status, impulsivity, general levels of risk and delinquent behavior which have all been shown to predict problematic gambling behavior (Auger et al. 2010; Ricijas et al. 2015). This would enable firmer conclusions about the efficacy of this prevention program, and provide more nuanced data about its universality.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on the development, implementation and outcome evaluation of youth gambling prevention programs, by presenting an original program developed and evaluated in Croatia. The “Who really wins?” prevention program is grounded on a clear and sound theoretical model for youth gambling prevention (Dickson et al. 2002, 2004), as well as widely established principles of prevention science (Nation et al. 2003; Greenberg et al. 2005; Domitrovich et al. 2010; Catalano et al. 2012). It incorporates both risk and protective factors associated with adolescent problem gambling, and can be classified as a comprehensive psychoeducational and skills training prevention program.

Short-term outcome evaluation showed a significant decrease in risk factors. The program significantly improved students’ knowledge about gambling consequences, dispelled their myths associated with gambling, and decreased cognitive distortions of all types (illusion of control, fallacies in probabilistic reasoning, and superstitious thinking). The program did not lead to any significant changes in intra- and interpersonal skills (self-efficacy, problem solving, peer pressure resistance) or gambling frequency right after its implementation. Follow-up studies are needed before firm conclusions about the effects of our program on behavior and skill change are drawn.

More importantly, our program did not have iatrogenic effects leading to more gambling. Also, we provided evidence about the universality of our program by showing its effects are the same for both boys and girls, students from different types of schools, for those with different learning aptitudes, as well as for those at different risk levels with regard to their gambling. So we can reasonably conclude that the “Who really wins?” represents a universal youth gambling prevention program.

Conducting this study in Croatia provided us with a research context characterized by a liberal market, and high availability and accessibility of gambling venues for adolescents, thus enabling us not only to expand previous literature on youth gambling prevention, but also to corroborate the effects of youth gambling prevention efforts from other countries. Our research findings are encouraging and in line with other prevention efforts showing that minimizing risk and empowering protective factors for problem gambling is a promising avenue for preventing adolescents from engaging in gambling activities (illegally) and consequently to become more responsible in their approach to gambling in the future (legally).

References

Allami, Y., & Vitaro, F. (2015). Pathways model to problem gambling: Clinical implications for treatment and prevention among adolescents. The Canadian Journal of Addiction, 6(2), 13–19.

Ariyabuddhiphongs, V. (2013). Problem gambling prevention: Before, during, and after measures. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. doi:10.1007/s11469-013-9429-2.

Auger, N., Lo, E., Cantinotti, M., & O’Loughlin, J. (2010). Impulsivity and socio-economic status interact to increase the risk of gambling onset among youth. Addiction, 105(12), 2176–2183. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03100.

Botvin, J. G., & Griffin, K. W. (2007). School-based programmes to prevent alcohol, tobacco and other drug use. International Review of Psychiatry, 19(6), 607–615.

Brotherhood, A., & Sumnall, H. R. (2011). European drug prevention quality standards. A manual for prevention professionals. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Calado, F., Alexandre, J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2016). Prevalence of adolescent problem gambling: A systematic review of recent research. Journal of Gambling Studies. doi:10.1007/s10899-016-9627-5.

Carbonneau, R., Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2015). Variety of gambling activities from adolescence to age 30 and association with gambling problems: A 15-year longitudinal study of a general population sample. Addiction, 110(12), 1985–1993.

Casey, B. J., Getz, S., & Galvan, A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Developmental Review (Special Issue: Current Directions in Risk and Decision Making), 28(1), 62–77.

Catalano, R. F., Fagan, A. A., Gavin, L. E., Greenberg, M. T., Irwin, C. E., Ross, D. A., et al. (2012). Adolescent health 3 Worldwide application of prevention science in adolescent health. Lancet, 379(9826), 1653–1664.

Caulkins, J. P., Liccardo Pacula, R., Paddock, S., & Chiesa, J. (2004). What we can—and cannot—Expect from school-based drug prevention. Drug and Alcohol Review, 23(1), 79–87.

Chen, C. (1998). Theory-driven evaluations. Advances in Educational Productivity, 7, 15–34.

Cordova, D., Estrada, Y., Malcom, S., Huang, S., Brown, C. H., Pantin, H., et al. (2014). Prevention science: An epidemiological approach. In Z. Sloboda & H. Petras (Eds.), Defining prevention science (pp. 1–23). New York: Springer.

Dariotis, J. K., Bumbarger, B. K., Duncan, L. G., & Greenberg, M. T. (2008). How do implementation efforts relate to program adherence? Examining the role of organizational, implementer, and program factors. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 745–761.

Delfabbro, P., King, D., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014). From adolescent to adult gambling: An analysis of longitudinal gambling patterns in South Australia. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(3), 547–563.

Derevensky, J. L., & Gilbeau, L. (2015). Adolescent gambling: Twenty-five years of research. The Canadian Journal of Addiction, 6(2), 4–12.

Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2000). Prevalence estimates of adolescent gambling: A comparison of the SOGS-RA, DSM-IV-J and the GA-20 Questions. Journal of Gambling Studies, 16(2–3), 227–251.

Derevensky, J. L., Gupta, R., Dickson, L., & Deguire, A. (2006). Prevention efforts toward reducing gambling problems. In J. L. Derevensky & R. Gupta (Eds.), Gambling problems in youth: Theoretical and applied perspectives. New York: Springer.

Dickson, L., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2002). The prevention of gambling problems in youth: A conceptual framework. Journal of Gambling Studies, 18(2), 97–159.

Dickson, L., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2004). Harm reduction for the prevention of youth gambling problems: Lessons learned from adolescent high-risk behavior prevention programs. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19(2), 233–263.

Dickson-Gillespie, L., Rugle, L., Rosenthal, R., & Fong, T. (2008). Preventing the incidence and harm of gambling problems. Journal of Primary Prevention, 29, 37–55.

Dodge, K. A., Godwin, J., & The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2013). Social-information-processing patterns mediate the impact of preventive intervention on adolescent antisocial behavior. Psychological Science, 24(4), 456–465.

Dodig, D. (2013a). Assessment challenges and determinants of adolescents’ adverse psychological consenquences of gambling. Criminology and Social Integration Journal, 21(2), 15–29.

Dodig, D. (2013b). Obiljezja kockanja mladih i odrednice stetnih psihosocijalnih posljedica/Characteristics of youth gambling and determinants of adverse psychosocial consequences. Doktorska disertacija/Doctoral Dissertation. Pravni fakultet Sveucilista u Zagrebu/Faculty of Law, University of Zagreb, Zagreb.

Domitrovich, C. E., Bradshaw, C. P., Poduska, J. M., Hoagwood, K., Buckley, J. A., Olin, S., et al. (2010). Integrated models of school-based prevention: Logic and theory. Psychology in the Schools, 47(1), 71–88.

Donati, M. A., Primi, C., & Chiesi, F. (2014). Prevention of problematic gambling behavior among adolescents: Testing the efficacy of an integrative intervention. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(4), 803–818.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432.

Eddy, M. J., Reid, J. B., & Curry, V. (2002). The etiology of youth antisocial behavior, delinquency, and violence and a public health approach to prevention. In M. R. Shinn, H. M. Walker, & G. Stoner (Eds.), Interventions for academic and behavior problems II: Preventive and remedial approaches (pp. 27–51). Washington, DC: National Association of School Psychologists.

Evans, R. I. (2003). Some theoretical models and constructs generic to substance abuse prevention programs for adolescents: Possible relevance and limitations for problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 19(3), 287–302.

Faggiano, F., Allara, E., Giannotta, F., Molinar, R., Sumnall, H., Wiers, R., et al. (2014). Europe needs a central, transparent, and evidence-based approval process for behavioural prevention interventions. PLoS Medicine, 11(10), e1001740. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001740.

Ferland, F., Ladouceur, R., & Vitaro, F. (2002). Prevention of problem gambling: Modifying misconceptions and increasing knowledge. Journal of Gambling Studies, 18(1), 19–29.

Foxcroft, D. R., & Tsertsvadze, A. (2012). Cochrane review: Universal school-based prevention programs for alcohol misuse in young people. Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal, 7(2), 450–575.

Gray, K. L., Oakley Browne, M. A., & Prabhu, V. R. (2007). Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on early intervention and prevention for problem gambling. Report prepared for Gambling Research Australia. Monash University Department of Rural and Indigenous Health.

Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C., Graczyk, P. A., & Zins, J. E. (2005). The study of implementation in school-based prevention research: Theory, research and practice. Volume 3 of Promotion of Mental Health and Prevention of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services.

Greenberg, M. T., Weissberg, R. P., O’Brien, M. U., Zins, J. E., Fredericks, L., Resnik, H., et al. (2003). Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. American Psychologist, 58(6–7), 466–474.

Griffiths, M. D. (1995). Adolescent gambling. London: Routledge.

Griffiths, M., & Wood, R. T. (2000). Risk factors in adolescence: The case of gambling, videogame playing, and the Internet. Journal of Gambling Studies, 16(2–3), 199–225.

Hale, D. R., Fitzgerald-Yau, N., & Viner, R. M. (2014). A systematic review of effective interventions for reducing multiple health risk behaviors in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health, 104(5), 19–41.

Hardoon, K., Gupta, R., & Derevensky, J. (2004). Psychosocial variables associated with adolescent gambling: A model for problem gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(2), 170–179.

Hawkins, J. D., Jenson, J. M., Catalano, R., Fraser, M. W., Botvin, G. J., Shapiro, V., et al. (2015). Unleashing the power of prevention. Discussion paper, Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, Washington, DC.

Igra, V., & Irwin, C. E. (1996). Theories of adolescent risk-taking behavior. In R. J. DiClemente, W. B. Hansen, & L. E. Ponton (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent health risk behavior (pp. 35–52). New York: Springer.

Jacobs, D. F. (2004). Youth gambling in North America: An analysis of long term trends and future prospects. In J. Derevensky & R. Gupta (Eds.), Gambling problems in youth: Theoretical and applied perspectives (pp. 1–26). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Jessor, R. (1987). Problem-behavior theory, psychosocial development, and adolescent problem drinking. British Journal of Addiction, 82(4), 331–342.

Keen, B., Blaszczynski, A., & Anjoul, F. (2016). Systematic review of empirically evaluated echool-based gambling education programs. Journal of Gambling Studies. Online publication date: 26 August 2016, doi:10.1007/s10899-016-9641-7. Accessed 23 December 2016.

Kirkpatrick, D. L., & Kirkpatrick, J. D. (2007). Implementing the four levels: A practical guide to effective training programs. San Francisco: Berett-Koehler Publishers.

Ladouceur, R., Goulet, A., & Vitaro, F. (2013). Prevention programs for youth gambling: A review of the empirical evidence. International Gambling Studies, 13(2), 141–159.

Merrell, K. W., Levitt, V. H., & Gueldner, B. A. (2012). Proactive strategies for promoting social competence and resilience. In G. Gimpel Peackok, R. A. Ervin, K. W. Merrell, & E. J. Daly III (Eds.), Practical handbook of school psychology: Effective practices for the 21st century. 273: 254.

Messerlian, C., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2005). Youth gambling problems: A public health perspective. Health Promotion International, 20(1), 69–79.

Moos, R. H. (2005). Iatrogenic effects of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders: Prevalence, predictors, prevention. Addiction, 100(5), 595–604.

Nation, M., Crusto, C., Wandresman, A., Kumpfer, K. L., Seybolt, D., Morisey-Kane, E., et al. (2003). What works in prevention: Principles of effective prevention programs. American Psychologist, 58(6/7), 449–456.

Nower, L., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2004). The relationship of impulsivity, sensation seeking, coping, and substance use in youth gamblers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(1), 49–55.

Rahman, A. S., Pilver, C. E., Desai, R. A., Steinberg, M. A., Rugle, L., Krishnan-Sarin, S., et al. (2012). The relationship between age of gambling onset and adolescent problematic gambling severity. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(5), 675–683.

Ricijas, N., & Dodig, D. (2014). Youth sports betting—The Croatian perspective. International Centre for Youth Gambling Problems and Hihg-Risk Behaviors, Vol. 14, No. 3. www.youthgambling.com

Ricijas, N., Dodig, D., Huic, A., & Kranzelic, V. (2011). Navike i obiljezja kockanja adolescenata u urbanim sredinama - izvjestaj o rezultatima istrazivanja. Project report. Zagreb: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Education and Rehabilitation Sciences. https://bib.irb.hr/prikazi-rad?&rad=654654. Accessed 19 June 2016.

Ricijas, N., Dodig Hundric, D., & Huic, A. (2016a). Predictors of adverse gambling related consequences among adolescent boys. Children and Youth Services Review, 67, 168–174.

Ricijas, N., Dodig Hundric, D., Huic, A., & Kranzelic, V. (2016b). Youth gambling in Croatia—Frequency of gambling and problem gambling occurrence. Criminology and Social Integration Journal, 24(2), 48–72.

Ricijas, N., Dodig Hundric, D., & Kranzelic, V. (2015). Sports betting and other risk behaviour among Croatian high-school students. Croatian Review of Rehabilitation Research, 15(2), 41–56.

Ricijas, N., Huic, A., Dodig, D., & Kranzelic, V. (2013). Osmisljavanje, implementacija i evaluacija preventivnog programa kockanja mladih „TKO ZAPRAVO POBJEĐUJE?“: projektni izvjestaj. Project report. Zagreb: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Education and Rehabilitation Sciences. https://bib.irb.hr/datoteka/654656.IZVJESTAJ_-_PREVENTIVNI_PROGRAM_2013.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2016.

Rivers, S. E., Reyna, V. F., & Mills, B. (2008). Risk taking under the influence: A fuzzy-trace theory of emotion in adolescence. Developmental Review (Special Issue: Current Directions in Risk and Decision Making), 28(1), 107–144.

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). Windsor: NFER-Nelson.

Scott, E. S., & Grisso, T. (2005). Developmental incompetence, due process, and juvenile justice policy. North Carolina Law Review, 83, 793–845.

Scott, E. S., & Steinberg, L. (2008). Rethinking juvenile justice. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shaffer, H. J., & Hall, M. N. (1996). Estimating the prevalence of adolescent gambling disorder: A quantitative synthesis and guide toward standard gambling nomenclature. Journal of Gambling Studies, 12(2), 193–214.

Shaffer, H., Hall, M., & Vander Bilt, J. (1997). Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behaviour in the United States and Canada: A meta-analysis. Boston: Harvard Press.

Shamblen, S. R., & Derzon, J. H. (2009). A preliminary study of the population-adjusted effectiveness of substance abuse prevention programming: Towards making IOM program types comparable. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 30(2), 89–107.

Steinberg, L. (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review (Special Issue: Current Directions in Risk and Decision Making), 28(1), 78–106.

Stoolmiler, M., Eddy, J. M., & Reid, J. B. (2000). Detecting and describing preventive intervention effects in a universal school-based randomized trial targeting delinquent and violent behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 296–306.

St-Pierre, R. A., & Derevensky, J. L. (2016). Youth gambling behavior: Novel approaches to prevention and intervention. Current Addiction Reports, 3(2), 157–165.

St-Pierre, R. A., Temcheff, C. E., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2015). Theory of planned behavior in school-based adolescent problem gambling prevention: A conceptual framework. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 36(6), 361–385.

Taylor, L. M., & Hillyard, P. (2009). Gambling awareness for youth: An analysis of the “Don’t Gamble Away our Future” Program. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7, 250–261.

Todirita, I. R., & Lupu, V. (2013). Gambling prevention program among children. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(1), 161–169.

Tremblay, J., Stinchfield, R., Wiebe, J., & Wynne, H. (2010). Canadian adolescent gambling inventory (CAGI) phase III final report. Submitted to the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and the Interprovincial Consortium on Gambling Research.

Turner, N. E., Macdonald, J., & Somerset, M. (2008). Life skills, mathematical reasoning and critical thinking: A curriculum for the prevention of problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 24(3), 367–380.

Uhl, A., Ives, R., & Members of the Pompidou Group Prevention Platform. (2010). Evaluation of drug prevention activities: Theory and practice. P-PG/Prev (2010)6. Council of Europe.

Valente, T. W., Ritt-Olson, A., Stacy, A., Unger, J. B., Okamoto, J., & Sussman, S. (2007). Peer acceleration: Effects of a social network tailored substance abuse prevention program among high-risk adolescents. Research report. Institute for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Department of Preventive Medicine, CA, USA. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01992.x

Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., Ladouceur, R., & Tremblay, R. E. (2001). Gambling, delinquency, and drug use during adolescence: Mutual influences and common risk factors. Journal of Gambling Studies, 17(3), 171–190.

Volberg, R. A., Gupta, R., Griffiths, M. D., Olason, D. T., & Delfabbro, P. (2010). An international perspective on youth gambling prevalence studies. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 22(1), 3–38.

Walther, B., Hanewinkel, R., & Morgenstern, M. (2012). Short-term effects of a school-based program on gambling prevention in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 599–605.

Werch, C. E., & Owen, D. M. (2002). Iatrogenic effects of alcohol and drug prevention programs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(5), 581–590.

WHO. (2004). Prevention of mental disorders: Effective interventions and policy options: Summary report. Geneva: World Health Organization Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in collaboration with the Prevention Research Centre of the Universities of Nijmegen and Maastricht.

Williams, R. J., West, B. L., & Simpson, R. I. (2012). Prevention of problem gambling: A comprehensive review of the evidence and identified best practices. Guelph, ON: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Williams, R. J., Wood, R. T., & Currie, S. R. (2010). Stacked deck: An effective, school-based program for the prevention of problem gambling. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(3), 109–125.

Wulfert, E., Blanchard, B., & Martell, C. (2003). Conceptualizing and treating pathological gambling: A motivationally enhanced cognitive-behavioral approach. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10(1), 61–72.

Acknowledgements

The presented study is part of the project which is financially and organisationally supported by the Ministry of Science, Education and Sports of the Republic of Croatia, Education and Teacher Training Agency, and Croatian Lottery, Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huic, A., Kranzelic, V., Dodig Hundric, D. et al. Who Really Wins? Efficacy of a Croatian Youth Gambling Prevention Program. J Gambl Stud 33, 1011–1033 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9668-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9668-4