Abstract

Given its serious implications for psychological and socio-emotional health, the prevention of problem gambling among adolescents is increasingly acknowledged as an area requiring attention. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is a well-established model of behavior change that has been studied in the development and evaluation of primary preventive interventions aimed at modifying cognitions and behavior. However, the utility of the TPB has yet to be explored as a framework for the development of adolescent problem gambling prevention initiatives. This paper first examines the existing empirical literature addressing the effectiveness of school-based primary prevention programs for adolescent gambling. Given the limitations of existing programs, we then present a conceptual framework for the integration of the TPB in the development of effective problem gambling preventive interventions. The paper describes the TPB, demonstrates how the framework has been applied to gambling behavior, and reviews the strengths and limitations of the model for the design of primary prevention initiatives targeting adolescent risk and addictive behaviors, including adolescent gambling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The prevention of problem gambling among youth has emerged as a significant area of concern in recent years. Evidence from international prevalence studies reveals that an identifiable proportion of adolescents gamble excessively and experience significant problems as a result. Current estimates suggest that approximately 0.4–8.1 % among adolescents aged 12–19 years meet diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling, and another 8–14 % are at risk for developing severe gambling problems (Volberg, Gupta, Griffiths, Ólason, & Delfabbro, 2010). Gambling problems are frequently associated with serious concomitant and subsequent health, psychological, and social problems. Specifically, adolescent gambling problems have been correlated with alcohol and substance use problems, academic problems, poor or disrupted family relationships, delinquency, risky sexual behaviors, mental health problems, and suicidal ideation and behaviors (Blinn-Pike, Worthy, & Jonkman, 2010; Cook et al., 2014; Shead, Derevensky, & Gupta, 2010). Untreated adolescent problem gambling has also been linked in prospective studies with criminal behavior (Wanner, Vitaro, Carbonneau, & Tremblay, 2009) and depression (Dussault, Brendgen, Vitaro, Wanner, & Tremblay, 2011) in young adulthood. The significant negative and long-lasting implications of adolescent gambling problems for health and well-being underscore the importance of prevention among this vulnerable population.

In response to this need, school-based educational and prevention initiatives have increasingly been made available (Williams, West, & Simpson, 2012). Despite their importance, empirical evidence for sustained changes in adolescent gambling and problem gambling behavior is limited. Considering that the principle goal of any prevention initiative is to decrease the incidence of potential problematic behavior, there is a clear need for the development of youth problem gambling prevention initiatives in the context of other established theoretical models in order to improve the likelihood of successful long-term outcomes.

This paper will review the existing empirical literature on the effectiveness of available school-based prevention programs for adolescent gambling. Given the limitations of existing preventive interventions, we will present an argument for consideration of the theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991, 2002) in the development of adolescent problem gambling prevention initiatives. Specifically, we will describe the TPB and will demonstrate how the framework has been applied to gambling behavior. Further, we will critically review the strengths and limitations of the model for the design of prevention initiatives targeting adolescent risk behaviors, including excessive gambling.

Prevention of Youth Gambling

Youth gambling prevention initiatives can be grouped into two broad categories: (a) gambling-specific psychoeducational prevention programs, and (b) gambling-specific psychoeducational and skills training prevention programs. The goal of gambling-specific psychoeducational prevention programs is to increase awareness or knowledge about gambling and issues related to problem gambling (Derevensky, Gupta, Dickson, & Deguire, 2004; Ladouceur, Goulet, & Vitaro, 2012). The underlying premise of this approach is that youth are usually misinformed about the risks of the targeted behavior and that educating them on the psychosocial consequences of the behavior will deter or postpone initiation (Lantz et al., 2000). Although the content is diverse, gambling-specific psychoeducational prevention programs generally present one or more of the following types of information: the nature of gambling, gambling odds and probabilities, erroneous cognitions and gambling fallacies, warning signs of problem gambling, and the consequences associated with excessive gambling (Derevensky et al., 2004; Ladouceur et al., 2012; Williams, Wood, & Currie, 2010).

In contrast to gambling-specific psychoeducational prevention programs, gambling-specific psychoeducational and skills training prevention programs recognize that misinformation or knowledge deficits are only one of many factors that are associated with the initiation of youth problem gambling, and therefore go beyond merely presenting factual information (Ladouceur et al., 2012; Williams, Connolly, Wood, Currie, & Davis, 2004). Their approach to the prevention of youth problematic behavior is to influence attitudes related to the behavior with a focus on skills development to cope with high-risk situations (Lantz et al., 2000). Gambling-specific psychoeducational and skills training prevention programs typically cover a broad scope of themes, which include enhancement of self-esteem and self-image, development of interpersonal skills to better cope with stressful life events, development of problem-solving and decision-making skills, and development of skills for resisting peer pressure (Derevensky et al., 2004; Ladouceur et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2010).

Effectiveness of Youth Gambling Prevention Programs

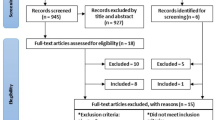

While a number of available youth gambling prevention initiatives have been implemented in school settings, there have been a limited number of published evaluations to date. A summary of studies investigating the effectiveness of gambling prevention programs is provided in Table 1.

Among the gambling-specific psychoeducational prevention programs that have been empirically evaluated, the majority have demonstrated improvements in participants’ knowledge about gambling and/or excessive gambling (Ferland, Ladouceur, & Vitaro, 2002; Ladouceur, Ferland, & Vitaro, 2004; Ladouceur, Ferland, Vitaro, & Pelletier, 2005; Lavoie & Ladouceur, 2004; Lemaire, de Lima, & Patton, 2004; Taylor & Hillyard, 2009; Turner, Macdonald, Bartoshuk, & Zangeneh, 2008; Vitaro, Paré, Trudelle, & Duchesne, 2005; Walther, Hanewinkel, & Morgenstern, 2013). Several of the prevention programs assessed have also shown reductions in participants’ erroneous cognitions or misconceptions about gambling (Ferland et al., 2002; Ladouceur, Ferland, & Fournier, 2003; Ladouceur, Ferland, Roy, Pelletier, Bussières, & Auclair, 2004; Ladouceur, Ferland, & Vitaro, 2004; Lavoie & Ladouceur, 2004; Lemaire et al., 2004; Todirita & Lupu, 2013; Vitaro et al., 2005; Walther et al., 2013). However, no study has demonstrated that these gains in knowledge or reductions in misconceptions are maintained over time. Although alterations in knowledge and misconceptions about gambling are assumed to be a precondition for eliciting changes in gambling behavior, only three studies (Turner, Macdonald, Bartoshuk, et al., 2008; Vitaro et al., 2005; Walther et al., 2013) have actually examined the effectiveness of existing programs in producing behavioral modifications. Of the programs that have been assessed, only one was successful in modifying gambling behavior by reducing the number of current gamblers immediately following the delivery of the intervention (Walther et al., 2013).

With regards to the gambling-specific psychoeducational and skills training prevention programs that have been empirically evaluated, almost all have shown improvements in participants’ knowledge about gambling and/or excessive gambling and reductions in their erroneous cognitions or misconceptions about gambling (Ferland, Ladouceur, & Vitaro, 2005; Gaboury & Ladouceur, 1993; Turner, Macdonald, & Somerset, 2008; Williams, 2002; Williams et al., 2004, 2010). In addition, there is some evidence that these improvements in knowledge or decreases in misconceptions are maintained for up to 6 months following the delivery of the program (Ferland et al., 2005; Gaboury & Ladouceur, 1993; Williams, 2002). A small number of the programs evaluated have also stimulated the development of more negative attitudes toward gambling (Williams, 2002; Williams et al., 2004, 2010). Certain prevention programs also produced actual behavioral changes, with concomitant improvement observed in participants’ coping, applied decision-making and problem-solving skills (Turner, Macdonald, & Somerset, 2008; Williams et al., 2010), as well as reductions in the frequency of gambling participation (Williams et al., 2004, 2010).

According to Nation et al. (2003) and Weissberg, Kumpfer, and Seligman (2003), there are several characteristics associated with effective youth prevention programs that have been identified in the literature. Such programs: (1) are comprehensive and incorporate a combination of interventions to address the salient precursors or mediators of the problem behavior; (2) use diverse teaching methods that focus on increasing awareness of the problem behavior and on acquiring or enhancing skills; (3) have a theoretical justification, are based on accurate information, and are supported by empirical research; (4) are tailored to the community, cultural norms and developmental stages of the participants, and make efforts to include the target group in program planning; and (5) adapt evidence-based programming through ongoing intervention evaluation and continuous quality improvement.

Based on the above characteristics, it is evident that the effectiveness of existing school-based problem gambling prevention initiatives needs to continue to be evaluated for the purpose of program refinement (Derevensky et al., 2004). Several of the empirical studies we reviewed lacked behavioral measures of gambling or follow-up evaluations after post-test measurement. Without measurement of gambling behavior and post-test follow-ups, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding the transfer of learning to actual gambling behavior or learning retention over time (Ladouceur et al., 2012).

Based on our review, there is also a clear need for the development of school-based problem gambling prevention initiatives in the context of theoretical models of behavioral change in order to improve the likelihood of sustained successful outcomes (Williams et al., 2010). Many of the existing prevention programs have been developed in the absence of a clear theoretical framework describing the expected causal mechanisms by which the program exerts its effect. While an underlying assumption of these programs is that changes in gambling knowledge and attitudes are a precondition for producing changes in gambling behavior, numerous investigations have documented weak correlations between individuals’ knowledge or attitudes and their actual behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977; Ajzen, Joyce, Sheikh, & Gilbert, 2011), and that knowledge alone does not predict behavior change (Ogden, 2012). However, even under conditions where a preventive intervention is “theory-based,” it is often unclear exactly how the theory was used in its development (Webb, Sniehotta, & Michie, 2010). Further, health and social cognition research has suggested that other factors can play an influential role in behavior change. These include: perceptions of risk in performing the behavior; notions of self-efficacy; and intentions or motivations to change the behavior (Ogden, 2012). As such, it is plausible that the effectiveness of existing prevention initiatives in changing adolescent gambling behavior is generally restricted because the initiatives fail to target all of the salient factors that influence behavior change. This situation has led gambling researchers to propose consideration of alternate models that could more accurately describe behavioral decision-making processes (Cummings & Corney, 1987; Evans, 2003). Social behavior theories, such as the TPB, are some of the most pervasive models for conceptualizing the causal pathways between beliefs and health behavior outcomes.

Theory of Planned Behavior

The TPB is a well-established social cognition framework used to explain and predict a range of human behaviors (Ajzen, 1991, 2002). The TPB is an extension of the earlier theory of reasoned action (TRA; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). The TRA proposes that the immediate determinant (or cause) of any volitional behavior is an individual’s intention to engage in that behavior. Behavioral intentions represent a person’s motivation, expressed as a conscious plan or decision, to exert effort in performing a specific behavior. Intentions to perform the behavior are themselves determined by two distinct factors: attitudes and subjective norms. Attitudes are the individual’s overall positive or negative evaluations of performing the focal behavior. Subjective norms consist of the individual’s perceptions of social pressure from important others to perform or not perform the behavior.

One limitation of the TRA is that it is restricted to the prediction of behaviors under an individual’s volitional control (i.e., the person can decide, at will, to perform or not perform the behavior). However, the performance of many behaviors depend to a certain extent on “environmental constraints” or factors extraneous to an individual’s intention or motivation, such as access to the necessary resources (e.g., time, money, skills) and opportunities to perform the behavior (Ajzen, 1991). To extend the applicability of the TRA to other behaviors outside of an individual’s complete control, the TPB incorporates the perception of control over performance of the behavior as an additional predictor. Perceptions of control, or perceived behavioral control (PBC), represent an individual’s expectations about the facility or difficulty related to performing a specific behavior. Ajzen (1991) proposes that PBC most closely resembles the concept of perceived self-efficacy. In the TPB, PBC is thought to influence performance of behaviors both directly and indirectly through an interaction with behavioral intentions. First, PBC is said to moderate the relationship between intentions and behavior such that behavioral intentions will increasingly predict behavior as perceptions of control over the behavior are strengthened. For example, the intention to quit smoking will be amplified as individuals perceive themselves to have control over their smoking behavior, which will increasingly lead to quitting behavior. The impact of PBC on behavior can also be direct where perceptions of control are accurate or realistic: when PBC is accurate, it provides useful information about the actual control an individual can exercise in the performance of a specific behavior (Ajzen, 2002). We provide an illustration of the proposed causal relationships within the TPB in Fig. 1.

Application of the TPB in the Prediction of Gambling Behaviors

The explanatory value of the TPB model for young adult gambling and disordered gambling behavior has received some empirical support. Martin et al. (2010) investigated the predictive relationships between key TPB components (i.e., attitudes, subjective norms, PBC, intentions) and past-year gambling participation, as well as the frequency of participation. They observed that gambling-related attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC were predictive of the frequency of gambling participation, and that intention to gamble mediated the relationship between gambling frequency and the other TPB determinants. Conversely, only subjective norms and PBC were significantly associated with past-year gambling, with the relationship between PBC and past-year gambling mediated by gambling intentions.

Consistent with Martin et al. (2010), Wu and Tang (2012) observed that positive gambling attitudes, positive subjective norms regarding gambling, and a poor sense of control over gambling refusal were predictive of intentions to gamble, accounting for approximately 56 % of the explained variance in gambling intentions. They also indicated that gambling intentions and perceived control over resisting gambling are the most proximal predictors of problem gambling behavior, and that gambling intentions mediate the relationship between problem gambling behavior and the other TPB determinants.

Of interest, Martin et al. (2011) observed differences in the explanatory value of the TPB between problem and non-problem young adult gamblers. Specifically, they found that for non-problem gamblers, attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC were predictive of gambling frequency, and that intention to gamble mediated the relationship between gambling frequency and the other TPB constructs. Conversely, for problem gamblers, intentions did not mediate the association between the components of the TPB and gambling frequency, as none of the TPB components were predictive of gambling intention. Rather, it was found that gambling-related attitudes independently predicted gambling frequency within this group.

To date, only one published study has explored the relationships between TPB components and gambling behavior among younger youth. Drawing from a sample of 757 secondary school and 250 university students aged 14–25, Moore and Ohtsuka (1997) found that intentions to gamble were modestly associated with gambling-related attitudes and subjective norms, accounting for 13–15 % of the explained variance. Additionally, they observed that gambling frequency was predicted most strongly by intentions to gamble (24–26 % of explained variance). It should, however, be noted that PBC was not included as a factor in the model.

The TPB in Adolescent Behavior Change Interventions

The TPB suggests that manipulations of attitudes, subjective norms, and control perceptions could potentially produce long-term changes in intentions and behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Montaño and Kasprzyk (2008) propose that for theory to adequately drive the intervention, it must provide a framework for the selection of salient factors that can be influenced from among the many possible factors associated with the behavior, and they suggest that the TPB is particularly useful in this regard. Additionally, Shek and Sun (2011) and Sun and Shek (2010, 2013) advocate for the incorporation of positive youth development constructs (e.g., promotion of cognitive competence, development of self-efficacy, fostering prosocial norms) in adolescent risk behavior prevention initiatives, and these positive youth development constructs parallel several of the TPB’s targets for intervention (e.g., attitudes and beliefs, subjective norms, PBC). Consequently, interest in the utility of the TPB model for adolescent behavioral change interventions has increased over the past few years.

A number of studies have applied the TPB to the development of preventive interventions aimed at modifying beliefs, intentions, and behaviors pertinent to several adolescent risk activities, or in the evaluation of these interventions. Targeted adolescent risk activities have included general risk-taking (Buckley, Sheehan, & Shochet, 2010; Chapman, Buckley, & Sheehan, 2012), unsafe driving (Poulter & McKenna, 2010; Sheehan et al., 1996), and risky sexual practices (Hill & Abraham, 2008; Jemmott, Jemmott, Braverman, & Fong, 2005; Jemmott, Jemmott, Fong, & McCaffree, 1999). However, the theory has been relatively neglected in the field of addiction (Webb et al., 2010). In one study, Cuijpers, Jonkers, De Weerdt, and De Jong (2002) evaluated a TPB-based prevention program designed to target secondary school students’ attitudes, social norms, and self-efficacy with respect to tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use. Results of their study at 3-year follow-up revealed a significant decrease in the proportion of students reporting daily tobacco use, weekly alcohol use, and monthly cannabis use for the intervention group but not the control group. Recently, Guo, Lee, Liao, and Huang (2015) evaluated the effects of a TPB-based substance-use preventive education program on enhancing students’ behavior intentions to abstain from illicit drug use and reducing their actual illicit drug use. They observed that students who received the prevention program demonstrated greater changes in their substance-related attitudes, subjective norms, PBC, and intentions over time than did those who received no intervention. Guo et al. also found that, compared to the control group, a significantly smaller proportion of participants in the TPB-based intervention group reported illicit drug use 6 months and 1 year following program delivery. These preliminary findings have prompted researchers to advocate for increased recognition of the value of behavior change theories such as the TPB in the development of interventions for addictive behaviors (Webb et al., 2010). Consideration of the TPB framework in the design and evaluation of prevention programs aimed at adolescent problem gambling is therefore warranted.

Strengths and Limitations of the TPB in Prevention Practice

As the literature suggests, the TPB is a valuable framework for the development of behavior change interventions, with research results indicating that the application of the model to behavioral interventions produces moderate changes in beliefs, intentions, and behaviors for youth risk activities and addictive behaviors. The planned behavior model is useful in intervention design because it provides important information about the primary beliefs that influence intentions to perform or not perform the behavior under consideration, and therefore allows for the selection of appropriate targets for intervention.

Additionally, the TPB offers advantages over other cognitive and behavior change models. For one, the TPB can be applied to situations where individuals may lack the intention to change or where their actual level of intention is unknown, situations that are common in the practice of primary prevention (Romano & Netland, 2008). Adolescents are frequently reported to fail to actively seek to change their problematic gambling behavior for multiple reasons, including the belief that that they can control their behavior, as well as adolescent self-perceptions of invincibility and invulnerability (Gupta & Derevensky, 2004; Hardoon, Derevensky, & Gupta, 2003). Additionally, problem gambling interventions have been criticized in the literature for their insufficient attention to the motivational factors that drive the behavior (Wulfert, Blanchard, & Martell, 2003). Because the TPB emphasizes the determinants of behavioral intentions, which leads to a better understanding of the factors related to behavior change, prevention activities can be designed for individuals or groups either ambivalent about or not motivated to change various behaviors, including gambling.

Further, in comparison to other change models, the TPB has a well-defined procedure for developing preventive interventions. The development of behavior change interventions using the TPB involves the identification of salient attitudes, perceived norms, control perceptions and intentions that explain the variance in the behavior of interest (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). This is achieved through qualitative and quantitative empirical research, called elicitation research, using samples that are representative of the population under consideration. Elicitation research is critical for the development of effective interventions since it would be counter-productive to target variables that do not account for a significant proportion of variance in behavioral intentions or behavior (Conner & Sparks, 2005), and allows the researcher or practitioner to identify the most culturally relevant variables of the group targeted for intervention (Romano & Netland, 2008). TPB elicitation research also facilitates the identification of subtle or important differences between those who engage in the behavior and those who do not, and this information can inform the content of the preventive intervention for each group. Much elicitation research has already been conducted and is described within the literature for adolescent gambling behaviors (see Shead et al., 2010; Volberg et al., 2010, for a review of previously identified risk and protective factors).

Although the procedure for designing interventions based on the planned behavior framework is well-described, it is imperative to note that the model does not specify the strategies or techniques to be used to elicit changes in the target behavior; the selection of intervention strategies remains at the discretion of each individual investigator, depending on the nature of the behavior and population, and on the resources available (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010; Webb et al., 2010). The TPB can therefore be considered more as a valuable framework for the identification of “cognitive targets for change” than as a model providing explicit guidelines on “how these cognitions might be changed” (Hardeman et al., 2002, p. 149). One proposed solution is to draw upon existing research that identifies the techniques judged to be most effective in changing behavioral determinants (Webb et al., 2010). While this approach remains in its infancy, certain techniques have been proposed as appropriate for changing specific TPB behavioral determinants (see Abraham & Michie, 2008; Hardeman et al., 2005; Michie, Johnston, Francis, Hardeman, & Eccles, 2008). Drawing from this literature, we provide in Table 2 a list and brief description of techniques that would be relevant to adolescent problem gambling prevention.

A second limitation of the TPB that has been increasingly acknowledged in the literature is the framework’s focus on the rational, cognitive processes for all health-related decision-making and action (Conner & Sparks, 2005). Researchers have suggested that a potential shortcoming of the theory is its failure to take into account emotional processes (Richard, de Vries, & van der Pligt, 1998; van der Pligt & de Vries, 1998), especially given evidence to suggest that anticipated affective reactions can influence behavioral decision-making (Josephs, Larrick, Steele, & Nisbett, 1992; Simonson, 1992). Negative anticipatory emotions (i.e., regret, guilt), in particular, are presumed to influence participation in high-risk or potentially addictive activities. Individuals are assumed to be motivated to avoid negative post-behavioral feelings, and consequently tend to make decisions that they anticipate will minimize the potential of experiencing subsequent negative emotions (Sandberg & Conner, 2008). Negative anticipatory emotions therefore have an important motivational effect in deterring individuals from making risky behavior choices without consideration of their potential affective consequences (Janis & Mann, 1977). Findings from a small body of empirical studies provide support for the significance of anticipated negative emotions in gambling decision-making and intentions (Li et al., 2010; Risen & Gilovich, 2007; Wolfson & Briggs, 2002). Results from other studies further demonstrate the importance anticipatory regret in the prediction of intentions to initiate or continue gambling participation over and above the effects of other proximal determinants of behavior, such as attitudes and subjective norms (Sheeran & Orbell, 1999; Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2004). However, while this body of research does reveal the importance of anticipated negative emotions in gambling decision-making and gambling intentions, the predictive utility of anticipatory emotions in explaining excessive gambling behavior remains unclear, and is an area for future prevention research.

Concluding Remarks

Researchers, mental health professionals, and public policy makers have increasingly acknowledged the necessity for adolescent problem gambling prevention initiatives given the widespread availability of opportunities to gamble and the serious consequences of excessive gambling for adolescents’ psychological and socio-emotional health. In response to this need, several school-based prevention initiatives have been developed. Their importance notwithstanding, many existing preventive interventions have been developed in the absence of a guiding theoretical framework. Among those that have been designed using such a framework, the majority are based on the social inoculation/cognitive model, which involves providing youth with necessary knowledge to prevent excessive gambling behavior, or the cognitive-behavioral model, which features problem-solving, decision-making, and self-control methods for limiting excessive play (Evans, 2003). However, evidence for sustained changes in adolescent gambling behavior is limited. Consideration of other theoretical models for the development of problem gambling preventive interventions is therefore warranted.

The TPB is a potentially viable framework for the development of school-based youth problem gambling prevention initiatives. Despite restricted knowledge about the applicability of the TPB to younger adolescents’ gambling-related intentions and behaviors, a growing body of research provides supportive evidence for the significance of attitudes towards, family and peer subjective norms related to, and perceptions of control over gambling in the prediction of youth intentions to initiate and continue participation in gambling activities. The TPB has also been demonstrated as an effective framework in intervention design for several youth risk and addictive behaviors. Finally, the TPB offers advantages over other cognitive and behavior change models. As previously noted, the TPB provides important information about the primary beliefs that influence behavioral intentions, and therefore allows for the selection of appropriate targets for intervention. It is plausible that the effectiveness of existing youth problem gambling prevention programs is limited, because they fail to target the most salient attitudes, subjective norms, and control perceptions found to influence gambling intentions and behaviors. Additionally, the TPB offers a framework for eliciting systemic change among groups with low motivation for change. Further, it provides a well-defined procedure for individualizing prevention initiatives for specific population groups or sub-groups. The need for empirical research investigating the utility of the TPB in the design of school-based youth problem gambling prevention initiatives remains clear.

References

Abraham, C., & Michie, S. (2008). A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology, 27, 379–387. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t.

Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32, 665–683. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 888–918. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ajzen, I., Joyce, N., Sheikh, S., & Gilbert, N. (2011). Knowledge and the prediction of behavior: The role of information accuracy in the theory of planned behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 33, 101–117. doi:10.1080/01973533.2011.568834.

Blinn-Pike, L., Worthy, S. L., & Jonkman, J. N. (2010). Adolescent gambling: A review of an emerging field of research. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47, 223–236. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.003.

Buckley, L., Sheehan, M., & Shochet, I. (2010). Short-term evaluation of a school-based adolescent injury prevention program: Determining positive effects or iatrogenic outcomes. Journal of Early Adolescence, 30, 834–853. doi:10.1177/0272431609361201.

Chapman, R. L., Buckley, L., & Sheehan, M. (2012). Developing safer passengers through a school-based injury prevention program. Safety Science, 50, 1857–1861. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2012.05.001.

Conner, M., & Sparks, P. (2005). Theory of planned behaviour and health behaviour. In M. Conner & P. Norman (Eds.), Predicting health behaviour (2nd ed., pp. 170–222). Maidenhead, BRK: Open University Press.

Cook, S., Turner, N. E., Ballon, B., Paglia-Boak, A., Murray, R., Adlaf, E. M., et al. (2014). Problem gambling among Ontario students: Associations with substance abuse, mental health problems, suicide attempts, and delinquent behaviours. Journal of Gambling Studies,. doi:10.1007/s10899-014-9483-0.

Cuijpers, P., Jonkers, R., De Weerdt, I., & De Jong, A. (2002). The effects of drug abuse prevention at school: The ‘Healthy School and Drugs’ project. Addiction, 97, 67–73. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00038.x.

Cummings, W. T., & Corney, W. (1987). A conceptual model of gambling behavior: Fishbein’s theory of reasoned action. Journal of Gambling Studies, 3, 190–201. doi:10.1007/bf01367440.

Derevensky, J. L., Gupta, R., Dickson, L., & Deguire, A.-E. (2004). Prevention efforts toward reducing gambling problems. In J. L. Derevensky & R. Gupta (Eds.), Gambling problems in youth (pp. 211–230). New York, NY: Springer.

Dussault, F., Brendgen, M., Vitaro, F., Wanner, B., & Tremblay, R. E. (2011). Longitudinal links between impulsivity, gambling problems and depressive symptoms: A transactional model from adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 130–138. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02313.x.

Evans, R. I. (2003). Some theoretical models and constructs generic to substance abuse prevention programs for adolescents: Possible relevance and limitations for problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 19, 287–302. doi:10.1023/a:1024207504890.

Ferland, F., Ladouceur, R., & Vitaro, F. (2002). Prevention of problem gambling: Modifying misconceptions and increasing knowledge. Journal of Gambling Studies, 18, 19–29. doi:10.1023/a:1014528128578.

Ferland, F., Ladouceur, R., & Vitaro, F. (2005). Efficacité d’un programme de prévention des habitudes de jeu chez les jeunes: Résultats de l’évaluation pilote. L’Encéphale, 31, 427–436. doi:10.1016/s0013-7006(05)82404-2.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Gaboury, A., & Ladouceur, R. (1993). Evaluation of a prevention program for pathological gambling among adolescents. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 14, 21–28. doi:10.1007/bf01324653.

Guo, J.-L., Lee, T.-C., Liao, J.-Y., & Huang, C.-M. (2015). Prevention of illicit drug use through a school-based program: Results of a longitudinal, cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, 314–322. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.003.

Gupta, R., & Derevensky, J. L. (2004). A treatment approach for adolescents with gambling problems. In J. L. Derevensky & R. Gupta (Eds.), Gambling problems in youth (pp. 165–188). New York, NY: Springer.

Hardeman, W., Johnston, M., Johnston, D., Bonetti, D., Wareham, N., & Kinmonth, A. L. (2002). Application of the theory of planned behaviour in behaviour change interventions: A systematic review. Psychology and Health, 17, 123–158. doi:10.1080/08870440290013644a.

Hardeman, W., Sutton, S., Griffin, S., Johnston, M., White, A., Wareham, N. J., & Kinmonth, A. L. (2005). A causal modelling approach to the development of theory-based behaviour change programmes for trial evaluation. Health Education Research, 20, 676–687. doi:10.1093/her/cyh022.

Hardoon, K., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2003). Empirical measures vs. perceived gambling severity among youth: Why adolescent problem gamblers fail to seek treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 28, 933–946. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00283-0.

Hill, C. A., & Abraham, C. (2008). School-based, randomised controlled trial of an evidence-based condom promotion leaflet. Psychology and Health, 23, 41–56. doi:10.1080/08870440701619726.

Janis, I. L., & Mann, L. (1977). Decision making: A psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and commitment. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Jemmott, J. B, I. I. I., Jemmott, L. S., Braverman, P. K., & Fong, G. T. (2005). HIV/STD risk reduction interventions for African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 159, 440–449. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.5.440.

Jemmott, J. B, I. I. I., Jemmott, L. S., Fong, G. T., & McCaffree, K. (1999). Reducing HIV risk-associated sexual behavior among African American adolescents: Testing the generality of intervention effects. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 161–187. doi:10.1007/bf02503158.

Josephs, R. A., Larrick, R. P., Steele, C. M., & Nisbett, R. E. (1992). Protecting the self from the negative consequences of risky decisions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 26–37. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.62.1.26.

Ladouceur, R., Ferland, F., & Fournier, P.-M. (2003). Correction of erroneous perceptions among primary school students regarding the notions of chance and randomness in gambling. American Journal of Health Education, 34(5), 272–277.

Ladouceur, R., Ferland, F., Roy, C., Pelletier, O., Bussières, E.-L., & Auclair, A. (2004). Prévention du jeu excessif chez les adolescents: Une approche cognitive. Journal de Thérapie Comportementale et Cognitive, 14, 124–130. doi:10.1016/S1155-1704(04)97459-9.

Ladouceur, R., Ferland, F., & Vitaro, F. (2004). Prevention of problem gambling: Modifying misconceptions and increasing knowledge among Canadian youths. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 25, 329–335. doi:10.1023/b:jopp.0000048024.37066.32.

Ladouceur, R., Ferland, F., Vitaro, F., & Pelletier, O. (2005). Modifying youths’ perception toward pathological gamblers. Addictive Behaviors, 30, 351–354. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.002.

Ladouceur, R., Goulet, A., & Vitaro, F. (2012). Prevention programmes for youth gambling: A review of the empirical evidence. International Gambling Studies, 13, 141–159. doi:10.1080/14459795.2012740496.

Lantz, P. M., Jacobson, P. D., Warner, K. E., Wasserman, J., Pollack, H. A., Berson, J., & Ahlstrom, A. (2000). Investing in youth tobacco control: A review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tobacco Control, 9, 47–63. doi:10.1136/tc.9.1.47.

Lavoie, M.-P., & Ladouceur, R. (2004). Prevention of gambling among youth: Increasing knowledge and modifying attitudes toward gambling. Journal of Gambling Issues, 10, 1–10. doi:10.4309/jgi.2004.10.7.

Lemaire, J., de Lima, S., & Patton, D. (2004). It’s your lucky day: Program evaluation. Retrieved from Addictions Foundation of Manitoba website http://www.afm.mb.ca/pdf/Lucky%20Day%20Report%202004.pdf.

Li, S., Zhou, K., Sun, Y., Rao, L.-L., Zheng, R., & Liang, Z.-Y. (2010). Anticipated regret, risk perception, or both: Which is most likely responsible for our intention to gamble? Journal of Gambling Studies, 26, 105–116. doi:10.1007/s10899-009-9149-5.

Martin, R. J., Nelson, S., Usdan, S., & Turner, L. (2011). Predicting college student gambling frequency using the theory of planned behavior: Does the theory work differently for disordered and non-disordered gamblers? Analysis of Gambling Behavior, 5(2), 45–58.

Martin, R. J., Usdan, S., Nelson, S., Umstattd, M. R., LaPlante, D., Perko, M., & Shaffer, H. (2010). Using the theory of planned behavior to predict gambling behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24, 89–97. doi:10.1037/a0018452.

Michie, S., Johnston, M., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., & Eccles, M. (2008). From theory to intervention: Mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Applied Psychology, 57, 660–680. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x.

Montaño, D. E., & Kasprzyk, D. (2008). Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (4th ed., pp. 67–96). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Moore, S. M., & Ohtsuka, K. (1997). Gambling activities of young Australians: Developing a model of behaviour. Journal of Gambling Studies, 13, 207–236. doi:10.1023/a:1024979232287.

Nation, M., Crusto, C., Wandersman, A., Kumpfer, K. L., Seybolt, D., Morrissey-Kane, E., & Davino, K. (2003). What works in prevention: Principles of effective prevention programs. Amercian Psychologist, 58, 449–456. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.449.

Ogden, J. (2012). Health psychology: A textbook (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Poulter, D. R., & McKenna, F. P. (2010). Evaluating the effectiveness of a road safety education intervention for pre-drivers: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 163–181. doi:10.1348/014466509X468421.

Richard, R., de Vries, N. K., & van der Pligt, J. (1998). Anticipated regret and precautionary sexual behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28, 1411–1428. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01684.x.

Risen, J. L., & Gilovich, T. (2007). Another look at why people are reluctant to exchange lottery tickets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 12–22. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.12.

Romano, J. L., & Netland, J. D. (2008). The application of the theory of reasoned action and planned behavior to prevention science in counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 36, 777–806. doi:10.1177/0011000007301670.

Sandberg, T., & Conner, M. (2008). Anticipated regret as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 589–606. doi:10.1348/014466607x258704.

Shead, N. W., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2010). Risk and protective factors associated with youth problem gambling. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 22(1), 39–58.

Sheehan, M. C., Schonfeld, C. C., Ballard, R., Schofield, F., Najman, J. M., & Siskind, V. (1996). A three year outcome evaluation of a theory based drink driving education program. Journal of Drug Education, 26(3), 295–312.

Sheeran, P., & Orbell, S. (1999). Augmenting the theory of planned behavior: Roles for anticipated regret and descriptive norms. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29, 2107–2142. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb02298.x.

Shek, D. T. L., & Sun, R. (2011). Prevention of gambling problems in adolescents: The role of problem gambling assessment instruments and positive youth development programs. In J. L. Derevensky, D. T. L. Shek, & J. Merrick (Eds.), Youth gambling: The hidden addiction (pp. 231–244). Berlin: De Gruuyter.

Simonson, I. (1992). The influence of anticipating regret and responsibility on purchase decisions. The Journal of Consumer Research, 19(1), 105–118.

Sun, R. C., & Shek, D. T. (2010). Life satisfaction, positive youth development, and problem behaviour among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 95, 455–474. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9531-9.

Sun, R. C., & Shek, D. T. (2013). Longitudinal influences of positive youth development and life satisfaction on problem behaviour among adolescents in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 114, 1171–1197. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0196-4.

Taylor, L., & Hillyard, P. (2009). Gambling awareness for youth: An analysis of the “Don’t Gamble Away our Future™” program. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7, 250–261. doi:10.1007/s11469-008-9184-y.

Todirita, I., & Lupu, V. (2013). Gambling prevention program among children. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29, 161–169. doi:10.1007/s10899-012-9293-1.

Turner, N., Macdonald, J., Bartoshuk, M., & Zangeneh, M. (2008). The evaluation of a 1-h prevention program for youth gambling. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 6, 238–243. doi:10.1007/s11469-007-9121-5.

Turner, N. E., Macdonald, J., & Somerset, M. (2005). Life skills, mathematical reasoning and critical thinking: Curriculum for the prevention of problem gambling. Guelph, ON: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Turner, N. E., Macdonald, J., & Somerset, M. (2008). Life skills, mathematical reasoning and critical thinking: A curriculum for the prevention of problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 24, 367–380. doi:10.1007/s10899-007-9085-1.

van der Pligt, J., & de Vries, N. K. (1998). Expectancy-value models of health behaviour: The role of salience and anticipated affect. Psychology and Health, 13, 289–305. doi:10.1080/08870449808406752.

Vitaro, F., Paré, R., Trudelle, S., & Duchesne, J. (2005). Évaluation des ateliers de sensibilisation sur les risques associés aux jeux de hasard et d’argent: Première partie. Montréal, QC: Agence de Développement de Réseaux locaux de Services de santé et de Services sociaux de Montréal, Direction de santé publique.

Volberg, R. A., Gupta, R., Griffiths, M. D., Ólason, D. T., & Delfabbro, P. (2010). An international perspective on youth gambling prevalence studies. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 22(1), 3–38.

Walther, B., Hanewinkel, R., & Morgenstern, M. (2013). Short-term effects of a school-based program on gambling prevention in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health,. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.11.009.

Wanner, B., Vitaro, F., Carbonneau, R., & Tremblay, R. E. (2009). Cross-lagged links among gambling, substance use, and delinquency from midadolescence to young adulthood: Additive and moderating effects of common risk factors. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23, 91–104. doi:10.1037/a0013182.

Webb, T. L., Sniehotta, F. F., & Michie, S. (2010). Using theories of behaviour change to inform interventions for addictive behaviours. Addiction, 105, 1879–1892. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03028.x.

Weissberg, R. P., Kumpfer, K. L., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2003). Prevention that works for children and youth: An introduction. Amercian Psychologist, 58, 425–432. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.425.

Williams, R. (2002). Prevention of problem gambling: A school-based intervention—Final report. Retrieved from Alberta Gaming Research Institute website https://uleth.ca/dspace/handle/10133/370.

Williams, R. J., Connolly, D., Wood, R. T., Currie, S., & Davis, R. M. (2004). Program findings that inform curriculum development for the prevention of problem gambling. Gambling Research, 16(1), 47–69.

Williams, R. J., West, B. L., & Simpson, R. I. (2012). Prevention of problem gambling: A comprehensive review of the evidence and identified best practices. Guelph, ON: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Williams, R., Wood, R., & Currie, S. (2010). Stacked deck: An effective, school-based program for the prevention of problem gambling. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31, 109–125. doi:10.1007/s10935-010-0212-x.

Wolfson, S., & Briggs, P. (2002). Locked into gambling: Anticipatory regret as a motivator for playing the National Lottery. Journal of Gambling Studies, 18, 1–17. doi:10.1023/a:1014548111740.

Wu, A. M. S., & Tang, C. S. (2012). Problem gambling of Chinese college students: Application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Gambling Studies, 28, 315–324. doi:10.1007/s10899-011-9250-4.

Wulfert, E., Blanchard, E. B., & Martell, R. (2003). Conceptualizing and treating pathological gambling: A motivationally enhanced cognitive behavioral approach. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10, 61–72. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80009-3.

Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2004). Consequences of regret aversion in real life: The case of the Dutch postcode lottery. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 93, 155–168. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2003.10.001.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Nathan Hall for his guidance and valuable feedback in the initial draft phases of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Financial support for preparation of this paper was provided by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC; Grant Number 430-2012-0467) and the Fonds québécois de recherche sur la société et la culture (FQRSC).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest, and that the manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

St-Pierre, R.A., Temcheff, C.E., Derevensky, J.L. et al. Theory of Planned Behavior in School-Based Adolescent Problem Gambling Prevention: A Conceptual Framework. J Primary Prevent 36, 361–385 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-015-0404-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-015-0404-5